Abstract

Cardiovascular-related mortality increases in the cold winter months, particularly in older adults. Previously, we reported that determinants of myocardial O2 demand, such as the rate-pressure product, increase more in older adults compared with young adults during cold stress. The aim of the present study was to determine if aging influences the coronary hemodynamic response to cold stress in humans. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography was used to noninvasively measure peak coronary blood velocity in the left anterior descending artery before and during acute (20 min) whole body cold stress in 10 young adults (25 ± 1 yr) and 11 older healthy adults (65 ± 2 yr). Coronary vascular resistance (diastolic blood pressure/peak coronary blood velocity), coronary perfusion time fraction (coronary perfusion time/R-R interval), and left ventricular wall stress were calculated. We found that cooling (via a water-perfused suit) increased left ventricular wall stress, a primary determinant of myocardial O2 consumption, in both young and older adults, although the magnitude of this increase was nearly twofold greater in older adults (change of 9.1 ± 3.5% vs. 17.6 ± 3.2%, P < 0.05, change from baseline in young and older adults and young vs. older adults). Despite the increased myocardial O2 demand during cooling, coronary vasodilation (decreased coronary vascular resistance) occurred only in young adults (3.22 ± 0.23 to 2.85 ± 0.18 mmHg·cm−1·s−1, P < 0.05) and not older adults (3.97 ± 0.24 to 3.79 ± 0.27 mmHg·cm−1·s−1, P > 0.05). Consistent with a blunted coronary vascular response, absolute coronary perfusion time tended to decrease (P = 0.13) and coronary perfusion time fraction decreased (P < 0.05) during cooling in older adults but not young adults. Collectively, these data suggest that older adults demonstrate an altered coronary hemodynamic response to acute cold stress.

Keywords: aging, thermal stress, transthoracic Dopple echocardiography, coronary circulation

the incidence of cardiovascular-related events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, increase in the cold winter months, particularly in older adults (10, 36, 43, 50). As cold can act as a trigger for angina (25), one possible mechanism underlying these associations may involve an altered regulation of the determinants of myocardial O2 supply and demand during cold stress with advancing age.

Previously, we (20, 48) reported that acute nonhypothermic cold stress increased rate-pressure product as well as cardiac preload and afterload in older adults but not young adults. Based on these findings, one would expect myocardial O2 supply to increase during cold stress in older adults. However, as aging is associated with an impaired ability to increase myocardial perfusion during some acute stressors (7, 9, 42, 46), the anticipated increases in myocardial O2 supply during cooling may not occur in older adults. Presently, the effect of cold stress on determinants of myocardial O2 supply, such as coronary blood flow regulation, in older adults has not been determined. Recent advances in transthoracic Doppler echocardiography now make it possible to obtain noninvasive estimates of coronary blood flow (21, 22, 32–34) and coronary flow perfusion time fraction (coronary perfusion time/R-R interval). Coronary flow perfusion time is a critical determinant of myocardial perfusion as increasing the duration of coronary perfusion is the only mechanism by which coronary flow can be elevated when the coronary dilatory reserve is exhausted (30).

Accordingly, the primary aim of this study was to noninvasively determine coronary hemodynamic responses to acute cold stress in young and older adults. We hypothesized that during acute cold stress, in which the myocardial O2 demand is increased more in older adults compared with young adults, the key determinants of coronary perfusion (i.e., coronary vascular tone) are not modified appropriately in older adults. Testing this hypothesis provides insights into a possible mechanism by which cold exposure may elicit greater increases in cardiovascular-related morbidity/mortality in older adults compared with young adults.

METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-one subjects participated in this study; 10 subjects were 18–35 yr old (young) and 11 subjects were 55–79 yr old (older). All were healthy, unmedicated, normotensive [blood pressure (BP) at rest <140/90 mmHg], nonsmokers, and nonobese (body mass index <30 kg/m2; Table 1). The Institutional Review Board of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine approved the experiments. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before testing. Experiments were performed after a minimum 4-h fast and 12- and 24-h abstinence from caffeine and alcohol, respectively.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Variable | Young Group | Older Group |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 8 men/2 women | 8 men/2 women |

| Age, yr | 25 ± 1 | 65 ± 2* |

| Height, cm | 176.4 ± 2.0 | 174.2 ± 2.1 |

| Body weight, kg | 75.9 ± 3.5 | 76.5 ± 3.7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 0.9 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 10 subjects/group.

P < 0.05 compared with the young group.

Experimental Protocol

Subjects were studied in the supine position while clothed in a high-density tube-lined water-perfused suit (Med-Eng Systems, Ottawa, ON, Canada). This suit clothed the entire body except the subject's head, hands, and feet and had two-way full-length zippers along the torso to allow access for echocardiography and assessment of coronary hemodynamics with minimal exposure of the chest to ambient conditions. Skin surface temperature was controlled by altering the temperature of the water perfusing the suit using a combination of an on-board heater and ice added directly to an external reservoir tank and circulator connected in series to a centrifugal magnetic pump. Suit water perfusion temperature was maintained at 35°C except when cooling was desired. All subjects performed a cooling trial, which consisted of a 6-min baseline period (water temperature: 35°C) followed by a cooling period (20 min, water temperature: 15°C, cooling trial). A subgroup of young (n = 5) and older (n = 4) subjects also performed an additional trial (control trial) in which water perfusion temperature was maintained at 35°C throughout the baseline (6 min) and experimental (20 min) periods (cooling and control trials were randomized). No less than 30 min elapsed between consecutive trials, during which time suit water perfusion temperature was maintained at 35°C. During data collection periods, BP and heart rate (HR) were measured every 2 min and oral and skin surface temperatures every 5 min. Echocardiography measurements were made at baseline as well as in the final 5 min of each trial (cooling and control trials).

Measurements

BP and HR.

BP was measured over the brachial artery (Dinamap). A three-lead ECG was used to measure HR. Rate-pressure product was calculated as the product of systolic BP and HR.

Temperature.

Oral temperature was measured using a thermocouple placed under the tongue. Skin surface temperature was measured as a weighted average of values recorded at four skin sites (chest, arm, thigh, and leg), (40).

Echocardiography and coronary hemodynamics.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed with a digital ultrasound system (iE33, Philips Ultrasound, Bothell, WA) using broadband sector ultrasound transducers (S5-2 for echo, 5.0–2.0 MHz and S8-3 for coronary flow velocity, 8.0–3.0 MHz) as previously described (32, 34). Cardiac images were recorded in multiple cross-sectional planes with the use of standard transducer positions (41). M-mode imaging from the parasternal view between the mitral valve and papillary muscle was used for the echocardiography examination. During this examination, the ultrasound beam was positioned perpendicular to the interventricular septum and left ventricular posterior wall, allowing a clear view of the left ventricular diameter during diastole and systole. Left ventricular internal diameter was measured at the furthest endocardium endpoints. Mean left ventricular wall stress was calculated as follows: {[systolic BP × (average of end-diastolic and end-systolic left ventricular diameters/2)]/mean left ventricular wall thickness} (39). Indexes of coronary blood flow were obtained after identification of the distal portion of the left anterior descending artery with color flow mapping (Fig. 1). For color Doppler flow mapping, the velocity range was set at ±19 cm/s. The color gain was adjusted to provide optimal imaging. The left ventricle was imaged in the long-axis cross section, and the ultrasound beam was inclined laterally. After the distal portion of the left anterior descending artery was located in the region of the apex of the left ventricle, care was taken to position the transducer in a manner that allowed a long-axis view of the artery. With a sample volume (2.0 mm) positioned over the color signal in the left anterior descending artery, coronary blood velocity (CBV) was measured at end expiration. The Doppler signal profiles of coronary blood flow during the diastolic portion of each cardiac cycle were analyzed using Pro Solv 3.0 to obtain CBV.

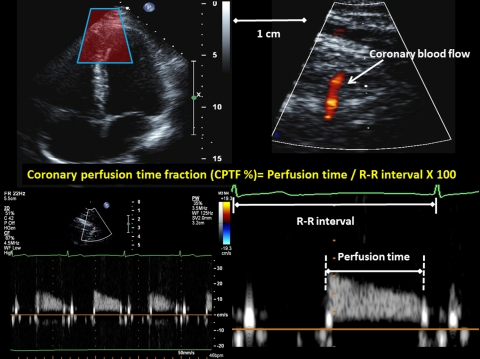

Fig. 1.

Original transthoracic Doppler echocardiogram (top) and coronary blood flow velocity (CBV) profile (bottom) demonstrating measurements of the coronary perfusion time fraction.

The peak and mean CBV, velocity time integral of CBV (VTI-CBV), and duration of coronary blood flow signals during diastole were measured (Fig. 1). The coronary perfusion time fraction was calculated as absolute coronary perfusion time/R-R interval × 100. Coronary vascular resistance (CVR) was calculated as diastolic BP/peak CBV. All coronary-derived data were averaged over three to five cardiac cycles (Fig. 1).

Intraobserver and Interobserver Variability and Reproducibility

A single experienced researcher performed all the coronary blood flow signal recordings and measurements. To assess intra- and interobserver variability, coronary hemodynamic variables (including peak CBV, VTI-CBV, mean CBV, and coronary perfusion time) from 10 randomized subjects were measured by 2 investigators separately. Reproducibility was assessed in six subjects under identical experimental conditions separated by 1–2 mo. The same researcher collected and analyzed both data sets (reproducibility).

Statistical Analysis

Independent t-tests were used to examine group differences (young compared with older adults) in subject characteristics. Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to assess the effects of the experiments. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. All data are reported as means ± SE. Intraclass correlation coefficients with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to test intra- and interobserver variability and to assess reproducibility. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

In addition to age differences, BPs in older subjects at rest were higher than those in young subjects (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Hemodynamics during the cooling trial

| Young Group |

Older Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline | Cooling | Baseline | Cooling |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 115 ± 2 | 122 ± 3* | 128 ± 4† | 147 ± 6* |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 65 ± 1 | 71 ± 2* | 73 ± 3† | 78 ± 3* |

| Mean BP, mmHg | 85 ± 1 | 90 ± 1* | 94 ± 3† | 102 ± 4* |

| HR, beats/min | 58 ± 3 | 59 ± 3 | 54 ± 3 | 52 ± 2* |

| R-R interval, ms | 1,057 ± 66 | 1,037 ± 47 | 1,130 ± 43 | 1,176 ± 38* |

| RPP, mmHg·beats·min−1 | 6,720 ± 343 | 7,203 ± 458 | 6,955 ± 491 | 7,614 ± 552* |

| Left ventricular wall stress, g/cm2 | 186 ± 6 | 204 ± 10* | 194 ± 9 | 229 ± 15*‡ |

| Peak CBV, cm/s | 21 ± 1 | 26 ± 1* | 18 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 |

| Mean CBV, cm/s | 15 ± 1 | 17 ± 1* | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| VTI-CBV, cm | 9 ± 1 | 11 ± 1* | 9 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 |

| Coronary perfusion time, ms | 537 ± 67 | 551 ± 48 | 598 ± 28 | 560 ± 32 |

| Coronary perfusion time fraction, % | 50 ± 4 | 53 ± 2 | 53 ± 2 | 48 ± 2* |

Values are means ± SE; n = 10 subjects/group. BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; RPP, rate-product pressure; CBV, coronary blood velocity; VTI-CBV, velocity time interval of CBV.

P < 0.05 vs. baseline (same age group);

P < 0.05 vs. the young group (at baseline);

P < 0.05 vs. change in the young group.

Among the 10 young adults and 11 older adults in who coronary measurements were attempted, adequate signals could be obtained in all but 1 older adult. Thus, data are presented for only 10 young adults and 10 older adults.

Effect of Skin Surface Cooling on Systemic Hemodynamics

Cooling decreased skin surface temperatures similarly in young adults (change: −2.5 ± 0.3°C) and older adults (change: −2.9 ± 0.3°C, P = 0.38, young vs. older adults) without affecting sublingual temperature in either group (change: −0.1 ± 0.1 vs. −0.1 ± 0.1°C for young and older adults, respectively, P = 0.62). Cooling elicited a pressor response (increase in BP) in young and older adults (P < 0.05), although the magnitude of this response was greater in older adults (systolic and mean BP; Table 2).

Rate-pressure product and left ventricular wall stress under resting thermoneutral conditions (i.e., before cooling) did not differ between young and older adults (Table 2). Cooling increased myocardial O2 demand significantly, as indicated by increased left ventricular wall stress (young and older adults; Table 2). Increases in left ventricular wall stress during cooling were greater in older adults compared with young adults (P < 0.05, young vs. older adults; Table 2). Furthermore, cooling increased rate-pressure product in older adults (P < 0.05). In contrast, no change in rate-pressure product was observed in young adults during cooling (Table 2).

No subject provided any indication of myocardial ischemia during the protocols. Consistent with this, no regional left ventricular wall motion abnormalities were observed before, during, or after the cooling trial.

Effect of Skin Surface Cooling on Coronary Hemodynamics

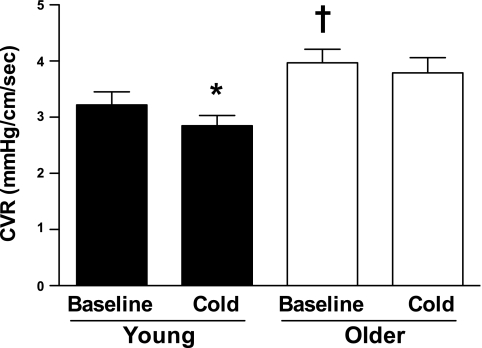

Peak CBV, mean CBV, VTI-CBV, coronary perfusion time, and coronary perfusion time fraction under resting thermoneutral conditions (i.e., before cooling) did not differ between young and older adults (Table 2 and Fig. 2). CVR was higher in older adults compared with young adults before cooling (Table 2). In response to cooling, peak CBV, mean CBV and VTI-CBV increased (all P < 0.05; Table 2), and CVR decreased in young adults (P < 0.05 compared with normothermia) but not older adults (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Coronary vascular resistance (CVR; diastolic blood pressure/peak CBV) before (baseline) and during cooling (cold) in young and older adults. Note that CVR, which was increased at rest (before cooling) in older adults, was significantly decreased during cold stress in only young adults. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline; †P < 0.05 vs. young adults under the same conditions (baseline or during cooling).

Under resting thermoneutral conditions, HR (and RR-interval) and absolute coronary perfusion time were similar in the young and older groups. Coronary perfusion time tended to decrease (P = 0.13) during cooling in older adults despite small, but statistically significant, increases in R-R interval. Coronary perfusion time fraction decreased during cooling in older but not young adults (P < 0.05, young compared with older adults; Fig. 2).

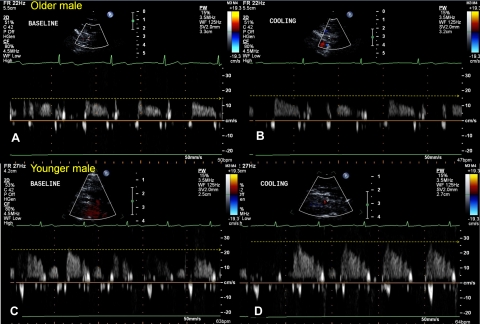

Representative recordings of CBV at baseline and during cooling from a young adults and an older adult are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Peak CBV at baseline (left) and during cooling (right) in a young adult (bottom) and an older adult (top). The original CBV profile in the left anterior descending artery is shown. Note that during cold stress peak CBV was higher before cooling (i.e., at baseline) in the young subject (C) compared with the older subject (A). Also note that peak CBV appeared to increase in the young adult (D) but not the older adult (B) during cold stress (compared with baseline).

Responses to the Control Trial

In response to the control trial (noncooling), all of the above-described variables were unchanged in both young and older adults (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hemodynamics during the control trial

| Young Group |

Older Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline | Control | Baseline | Control |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 114 ± 2 | 114 ± 2 | 129 ± 4* | 126 ± 7 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 66 ± 1 | 67 ± 1 | 76 ± 3* | 74 ± 4 |

| Mean BP, mmHg | 86 ± 1 | 86 ± 1 | 96 ± 3* | 90 ± 2 |

| HR, beats/min | 58 ± 5 | 56 ± 5 | 51 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 |

| R-R interval, ms | 1,102 ± 121 | 1,082 ± 131 | 1,159 ± 64 | 1,152 ± 75 |

| RPP, mmHg·beats·min−1 | 6,650 ± 690 | 6,440 ± 640 | 6,568 ± 548 | 6,522 ± 571 |

| Left ventricular wall stress, g/cm2 | 179 ± 4 | 180 ± 4 | 192 ± 26 | 198 ± 25 |

| Peak CBV, cm/s | 20 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 19 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 |

| Mean CBV, cm/s | 13 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| VTI-CBV, cm | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

| Coronary perfusion time, ms | 594 ± 12 | 592 ± 12 | 571 ± 16 | 561 ± 44 |

| Coronary perfusion time fraction, % | 52 ± 7 | 53 ± 6 | 51 ± 4 | 50 ± 4 |

| Coronary vascular resistance, mmHg·cm−1·s−1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 5 subjects in the young group and 4 subjects in the older group. Coronary vascular resistance was calculated as diastolic BP/CBV.

P < 0.05 vs. the young group (at baseline).

Interobserver and Intraobserver Variability and Reproducibility

Table 4 shows intraclass correlation coefficients, with 95% confidence intervals, for inter- and intraobserver variability and reproducibility. All intraclass correlation coefficient values were >0.8, which is considered excellent agreement (14).

Table 4.

Intraclass correlation coefficient values and 95% confidence intervals

| Intraobserver variability |

Interobserver Variability |

Reproducibility |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Intraclass correlation coefficient | 95% Confidence interval | Intraclass correlation coefficient | 95% Confidence interval | Intraclass correlation coefficient | 95% Confidence interval |

| Peak CBV, cm/s | 0.95 | 0.81–0.99 | 0.97 | 0.89–0.99 | 0.82 | 0.17–0.97 |

| Mean CBV, cm/s | 0.94 | 0.79–0.99 | 0.94 | 0.82–0.98 | 0.82 | 0.17–0.97 |

| VTI-CBV, cm | 0.95 | 0.81–0.99 | 0.96 | 0.87–0.99 | 0.82 | 0.18–0.97 |

| Coronary perfusion time, ms | 0.91 | 0.69–0.98 | 0.96 | 0.89–0.99 | 0.88 | 0.38–0.98 |

| Coronary perfusion time fraction, % | 0.82 | 0.45–0.95 | 0.89 | 0.65–0.96 | 0.90 | 0.47–0.99 |

DISCUSSION

The primary new finding of the present study is that aging is associated with an altered coronary hemodynamic response to acute whole body cold stress in healthy humans. This altered coronary hemodynamic response to cold stress includes an impaired coronary vasodilatory response that is associated with unchanged peak CBV and CVR in the left anterior descending artery. This impaired coronary vasodilator response to cold stress in older adults occurs at a time when myocardial O2 demand (rate-pressure product and left ventricular mean wall stress) is increasing. In contrast, young adults demonstrate a coronary vasodilator response (i.e., increased myocardial O2 supply) to cold stress when myocardial O2 demand (i.e., left ventricular mean wall stress) is only slightly increasing.

Myocardial O2 demand appears to increase more in older adults compared with young adults during acute cold stress. In the present study, cold stress resulted in an augmented pressor response (systolic and mean BP) and a greater increase in rate-pressure product in older adults compared with young adults, consistent with our previous findings (20, 48). As the same cooling protocol has been shown to increase left ventricular end-diastolic volume and indexes of afterload in older adults but not young adults (48), it appears that myocardial O2 demand increases to a greater extent in older adults during cold stress. The present study confirms these prior findings and extends them by showing that left ventricular mean wall stress increases more in older adults compared with young adults during cold stress. This finding is important, as left ventricular mean wall stress is a primary determinant of myocardial O2 consumption (31, 39, 44).

Despite greater increases in myocardial O2 demand in older adults compared with young adults during cold stress, myocardial O2 supply appears to increase only in young adults. The mechanisms underlying this impaired coronary vasodilator response to cold stress in older adults is unclear, but it does not appear to represent a generalized inability of coronary vessels to vasodilate (12). Additionally, although coronary vasodilation may still occur during other types of stressors, prior studies (6, 42) have indicated that the magnitude of vasodilation may be impaired with age. Altered coronary vasodilation during any stressor, such as acute cold stress, could involve a number of mechanism(s), such as 1) morphological changes in coronary vessels, 2) altered endothelium-mediated vasodilation, and 3) altered or unopposed sympathetic nervous system responses with advancing age.

Morphological changes in blood vessels may contribute to an impaired vasodilatory response to cold stress in older adults. Animal studies (2, 45) have provided strong evidence that aging reduces arteriolar density and increases collagen content in the arteriolar wall, which may impair coronary vasodilator capacity. Additionally, an anatomic study (3) reported that the vessel wall thickness of small arteries increases with age in humans. Consistent with these findings, we (20) previously reported strong associations between enhanced pressor responses to cold stress with age in humans and levels of central arterial stiffness. Thus, it is possible that structural changes in the coronary vasculature may occur with age in humans, which could contribute in part to an impaired ability of the coronary vessels to vasodilate during cold stress.

Endothelial dysfunction may contribute to an impaired coronary vasodilator response to cold stress in older adults. In coronary vessels, it appears that increases in vascular shear stress elicit blunted hyperemic responses in older rats compared with young rats (8). As coronary vascular shear forces may increase during cold stress, alterations in endothelial function with advancing age may contribute to an impaired coronary vasodilator response. The mechanism by which endothelial dysfunction occurs with age in humans is multifactorial but likely involves oxidative stress (4, 19). Recent evidence has suggested that at least a portion of the attenuated coronary vasodilation may be due to increases in ROS and its subsequent effects on nitric oxide (26, 29). In humans, ascorbic acid reduces the constriction of epicardial arteries in response to a cold pressor test (submerging the hand in ice water) in both hypertensive and hypercholesterolemia patients (24). Moreover, impairments in endothelium-dependent dilation with age in peripheral blood vessels, such as the brachial artery, are largely reversed by ascorbic acid (15). Collectively, these data indicate that endothelial dysfunction, as a result of increased oxidative stress, may contribute to impaired coronary vasodilatory responses to cold stress in older adults.

It is possible that the blunted coronary vasodilator response to cold stress in older adults could be mediated via the sympathetic nervous system. There are at least three ways by which the sympathetic nervous system may be involved. The first involves potential group differences in sympathetic outflow responses to cold stress. The direct effect of skin cooling on cardiac sympathetic nerve activity is presently unknown. However, it is well known that cold elicits sympathoexcitation (13), which vasoconstricts various organs of the body (49). In the anesthetized rat, skin surface cooling directly increases HR (38). This HR effect is generally not observed in human studies, and making group comparisons in the HR responses is made more difficult as a result of group differences in baroreflex function (35). Second, coronary arteries in older adults may lose their ability to oppose adrenergic vasoconstriction (16) as a result of endothelial dysfunction. For example, nitric oxide is present throughout the coronary vasculature (28), and thus a loss in the ability of vessels to generate nitric oxide may result in relatively less opposition to sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction in older adults compared with young adults. Finally, coronary sympathetic outflow may produce β-adrenergically mediated vasodilation. It is possible that β-adrenergically mediated vasodilation is impaired with age as a result of loss and/or desensitization of β-adrenergic receptors (51).

Myocardial perfusion occurs predominantly in diastole. Myocardial perfusion time or duration have not been previously reported, likely as a result of technical limitations. Instead, prior studies (5, 17, 18, 27, 30) measured diastolic perfusion time or diastolic time fraction invasively from intraventricular or coronary pressure curves or phonocardiograms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use transthoracic Doppler echocardiography to measure the duration of coronary flow perfusion. We believe that the coronary perfusion time fraction is similar in principle to the diastolic time fraction. We also believe that echocardiographically derived coronary perfusion time fraction may hold several advantages over measures of diastolic perfusion time: 1) the technique is noninvasive; 2) the profiles of the coronary blood flow signal obtained via echocardiography captures the true duration or time of coronary perfusion at the measured levels, unlike diastolic perfusion time, which may also include isovolumic systolic or diastolic periods; and 3) the sampling locations are more distally located in the vascular tree and thus in closer proximity to the coronary microcirculation.

In addition to an impaired ability of coronary vessels to dilate, for the reasons described above, during cold stress in older adults other factors may also contribute. For instance, previous studies (18, 27, 30) have suggested that modulation of diastolic time fraction is an important mechanism engaged to maintain the balance between myocardial O2 supply and demand. Consistent with this fact, diastolic time fraction and coronary perfusion are inversely related (30). In the present study, we observed a reduction in coronary perfusion time fraction and a trend for a reduction in absolute coronary perfusion time in older adults during cold stress. It is possible that this factor may have contributed in part to the impaired coronary vasodilator response to cold stress in older adults, although the exact role played cannot be determined.

The role of coronary zero-flow pressure in coronary vascular regulation is largely unknown (11, 16, 23). Van Herck et al. (47) found that increased coronary zero-flow pressure might impair myocardial perfusion in patients after myocardial infarction, which may influence the timing of coronary perfusion. In the present study, we estimate that zero-flow pressure increased only slightly during cooling in older adults (≈3 mmHg), based on previous human studies (37, 47). Thus, we do not believe that this factor explains our findings.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small. We did not observe sex differences in this study, but subject number may have underpowered this observation, as some coronary hemodynamic differences (32) have been observed. Second, the results of this study may not be applicable to populations not represented in our sample. For example, all of our subjects were Caucasian. Thus, extrapolation of our findings to other ethnicities should be done with caution, as a previous study (1) observed racial differences in response to other types of cold stress (cold pressor test). Finally, our cooling paradigm was unique, and thus the results of the study may not apply to other forms of cooling that may differ in application.

In conclusion, the primary new finding of the present study is that older adults demonstrate an impaired coronary vasodilatory response to acute cold stress compared with young adults. The mechanisms underlying this impaired dilator response may involve an impaired ability of coronary vessels to increase blood flow. This lack of an increase in myocardial O2 supply in older adults during cooling occurs at a time when myocardial O2 demand (rate-pressure product and left ventricular mean wall stress) is increasing. These findings suggest that aging may detrimentally alter the balance between myocardial O2 supply and demand during acute cold stress.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-92309, AG-24420, and HL-70222.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Z.G. and K.D.M. performed experiments; Z.G., R.C.D., and J.E. analyzed data; Z.G., T.E.W., R.C.D., and K.D.M. interpreted results of experiments; Z.G. prepared figures; Z.G., T.E.W., and K.D.M. drafted manuscript; Z.G., T.E.W., R.C.D., J.E., and K.D.M. edited and revised manuscript; Z.G., T.E.W., R.C.D., J.E., and K.D.M. approved final version of manuscript; T.E.W. and K.D.M. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study participants for volunteering to participate in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamopoulos D, Ngatchou W, Lemogoum D, Janssen C, Beloka S, Lheureux O, Kayembe P, Argacha JF, Degaute JP, van de Borne P. Intensified large artery and microvascular response to cold adrenergic stimulation in African blacks. Am J Hypertens 22: 958–963, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anversa P, Li P, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G. Effects of aging on quantitative structural properties of coronary vasculature and microvasculature in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H1062–H1073, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Auerbach O, Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. Thickening of walls of arterioles and small arteries in relation to age and smoking habits. N Engl J Med 278: 980–984, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brandes RP, Fleming I, Busse R. Endothelial aging. Cardiovasc Res 66: 286–294, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruinsma P, Arts T, Dankelman J, Spaan JA. Model of the coronary circulation based on pressure dependence of coronary resistance and compliance. Basic Res Cardiol 83: 510–524, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buxton DB. Blunted response of myocardial perfusion to dipyridamole in older adults. J Nucl Med 33: 1425–1427, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chareonthaitawee P, Kaufmann PA, Rimoldi O, Camici PG. Heterogeneity of resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in healthy humans. Cardiovasc Res 50: 151–161, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res 90: 1159–1166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Czernin J, Muller P, Chan S, Brunken RC, Porenta G, Krivokapich J, Chen K, Chan A, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Influence of age and hemodynamics on myocardial blood flow and flow reserve. Circulation 88: 62–69, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danet S, Richard F, Montaye M, Beauchant S, Lemaire B, Graux C, Cottel D, Marecaux N, Amouyel P. Unhealthy effects of atmospheric temperature and pressure on the occurrence of myocardial infarction and coronary deaths. A 10-year survey: the Lille-World Health Organization MONICA project (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease). Circulation 100: E1–E7, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Domenech RJ. Regional diastolic coronary blood flow during diastolic ventricular hypertension. Cardiovasc Res 12: 639–645, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev 88: 1009–1086, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Durand S, Cui J, Williams KD, Crandall CG. Skin surface cooling improves orthostatic tolerance in normothermic individuals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R199–R205, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eliasziw M, Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K. Statistical methodology for the concurrent assessment of interrater and intrarater reliability: using goniometric measurements as an example. Phys Ther 74: 777–788, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eskurza I, Monahan KD, Robinson JA, Seals DR. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid on flow-mediated dilatation with sedentary and physically active human ageing. J Physiol 556: 315–324, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feigl EO. Coronary physiology. Physiol Rev 63: 1–205, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferro G, Duilio C, Spinelli L, Liucci GA, Mazza F, Indolfi C. Relation between diastolic perfusion time and coronary artery stenosis during stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Circulation 92: 342–347, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fokkema DS, Van Teeffelen JW, Dekker S, Vergroesen I, Reitsma JB, Spaan JA. Diastolic time fraction as a determinant of subendocardial perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2450–H2456, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harman D. The free radical theory of aging. Antioxid Redox Signal 5: 557–561, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hess KL, Wilson TE, Sauder CL, Gao Z, Ray CA, Monahan KD. Aging affects the cardiovascular responses to cold stress in humans. J Appl Physiol 107: 1076–1082, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hozumi T, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, Asami Y, Ogata Y, Takagi T, Kaji S, Kawamoto T, Ueda Y, Morioka S. Noninvasive assessment of coronary flow velocity and coronary flow velocity reserve in the left anterior descending coronary artery by Doppler echocardiography: comparison with invasive technique. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 1251–1259, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hozumi T, Yoshida K, Ogata Y, Akasaka T, Asami Y, Takagi T, Morioka S. Noninvasive assessment of significant left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis by coronary flow velocity reserve with transthoracic color Doppler echocardiography. Circulation 97: 1557–1562, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jeremy RW, Hughes CF, Fletcher PJ. Effects of left ventricular diastolic pressure on the pressure-flow relation of the coronary circulation during physiological vasodilatation. Cardiovasc Res 20: 922–930, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeserich M, Schindler T, Olschewski M, Unmussig M, Just H, Solzbach U. Vitamin C improves endothelial function of epicardial coronary arteries in patients with hypercholesterolaemia or essential hypertension–assessed by cold pressor testing. Eur Heart J 20: 1676–1680, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Juneau M, Johnstone M, Dempsey E, Waters DD. Exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in a cold environment. Effect of antianginal medications. Circulation 79: 1015–1020, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kang LS, Reyes RA, Muller-Delp JM. Aging impairs flow-induced dilation in coronary arterioles: role of NO and H2O2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1087–H1095, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kolyva C, Verhoeff BJ, Spaan JA, Piek JJ, Siebes M. Increased diastolic time fraction as beneficial adjunct of alpha1-adrenergic receptor blockade after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2054–H2060, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laughlin MH, Turk JR, Schrage WG, Woodman CR, Price EM. Influence of coronary artery diameter on eNOS protein content. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1307–H1312, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. LeBlanc AJ, Shipley RD, Kang LS, Muller-Delp JM. Age impairs Flk-1 signaling and NO-mediated vasodilation in coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2280–H2288, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Merkus D, Kajiya F, Vink H, Vergroesen I, Dankelman J, Goto M, Spaan JA. Prolonged diastolic time fraction protects myocardial perfusion when coronary blood flow is reduced. Circulation 100: 75–81, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michaels AD, McKeown B, Kostal M, Vakharia KT, Jordan MV, Gerber IL, Foster E, Chatterjee K. Effects of intravenous levosimendan on human coronary vasomotor regulation, left ventricular wall stress, and myocardial oxygen uptake. Circulation 111: 1504–1509, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Momen A, Gao Z, Cohen A, Khan T, Leuenberger UA, Sinoway LI. Coronary vasoconstrictor responses are attenuated in young women as compared with age-matched men. J Physiol 588: 4007–4016, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Momen A, Kozak M, Leuenberger UA, Ettinger S, Blaha C, Mascarenhas V, Lendel V, Herr MD, Sinoway LI. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography to noninvasively assess coronary vasoconstrictor and dilator responses in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H524–H529, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Momen A, Mascarenhas V, Gahremanpour A, Gao Z, Moradkhan R, Kunselman A, Boehmer JP, Sinoway LI, Leuenberger UA. Coronary blood flow responses to physiological stress in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H854–H861, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Monahan KD. Effect of aging on baroreflex function in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R3–R12, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morabito M, Modesti PA, Cecchi L, Crisci A, Orlandini S, Maracchi GGFG. Relationships between weather and myocardial infarction: a biometeorological approach. Int J Cardiol 105: 288–293, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol 30: 1527–1533, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakamura K, Morrison SF. Central efferent pathways mediating skin cooling-evoked sympathetic thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R127–R136, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quinones MA, Mokotoff DM, Nouri S, Winters WL, Jr, Miller RR. Noninvasive quantification of left ventricular wall stress. Validation of method and application to assessment of chronic pressure overload. Am J Cardiol 45: 782–790, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramanathan NL. A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. J Appl Physiol 19: 531–533, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation 58: 1072–1083, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Senneff MJ, Geltman EM, Bergmann SR. Noninvasive delineation of the effects of moderate aging on myocardial perfusion. J Nucl Med 32: 2037–2042, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sheth T, Nair C, Muller J, Yusuf S. Increased winter mortality from acute myocardial infarction and stroke: the effect of age. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1916–1919, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Strauer BE, Beer K, Heitlinger K, Hofling B. Left ventricular systolic wall stress as a primary determinant of myocardial oxygen consumption: comparative studies in patients with normal left ventricular function, with pressure and volume overload and with coronary heart disease. Basic Res Cardiol 72: 306–313, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tomanek RJ, Searls JC, Lachenbruch PA. Quantitative changes in the capillary bed during developing, peak, and stabilized cardiac hypertrophy in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circ Res 51: 295–304, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uren NG, Camici PG, Melin JA, Bol A, de Bruyne B, Radvan J, Olivotto I, Rosen SD, Impallomeni M, Wijns W. Effect of aging on myocardial perfusion reserve. J Nucl Med 36: 2032–2036, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Van Herck PL, Carlier SG, Claeys MJ, Haine SE, Gorissen P, Miljoen H, Bosmans JM, Vrints CJ. Coronary microvascular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: increased coronary zero flow pressure both in the infarcted and in the remote myocardium is mainly related to left ventricular filling pressure. Heart 93: 1231–1237, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilson TE, Gao Z, Hess KL, Monahan KD. Effect of aging on cardiac function during cold stress in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R1627–R1633, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wilson TE, Sauder CL, Kearney ML, Kuipers NT, Leuenberger UA, Monahan KD, Ray CA. Skin-surface cooling elicits peripheral and visceral vasoconstriction in humans. J Appl Physiol 103: 1257–1262, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolf K, Schneider A, Breitner S, von Klot S, Meisinger C, Cyrys J, Hymer H, Wichmann HE, Peters A. Air temperature and the occurrence of myocardial infarction in Augsburg, Germany. Circulation 120: 735–742, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xiao RP, Lakatta EG. Deterioration of β-adrenergic modulation of cardiovascular function with aging. Ann NY Acad Sci 673: 293–310, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]