Abstract

The mechanism(s) for post-bed rest (BR) orthostatic intolerance is equivocal. The vestibulosympathetic reflex contributes to postural blood pressure regulation. It was hypothesized that muscle sympathetic nerve responses to otolith stimulation would be attenuated by prolonged head-down BR. Arterial blood pressure, heart rate, muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), and peripheral vascular conductance were measured during head-down rotation (HDR; otolith organ stimulation) in the prone posture before and after short-duration (24 h; n = 22) and prolonged (36 ± 1 day; n = 8) BR. Head-up tilt at 80° was performed to assess orthostatic tolerance. After short-duration BR, MSNA responses to HDR were preserved (Δ5 ± 1 bursts/min, Δ53 ± 13% burst frequency, Δ65 ± 13% total activity; P < 0.001). After prolonged BR, MSNA responses to HDR were attenuated ∼50%. MSNA increased by Δ8 ± 2 vs. Δ3 ± 2 bursts/min and Δ83 ± 12 vs. Δ34 ± 22% total activity during HDR before and after prolonged BR, respectively. Moreover, these results were observed in three subjects tested again after 75 ± 1 days of BR. This reduction in MSNA responses to otolith organ stimulation at 5 wk occurred with reductions in head-up tilt duration. These results indicate that prolonged BR (∼5 wk) unlike short-term BR (24 h) attenuates the vestibulosympathetic reflex and possibly contributes to orthostatic intolerance following BR in humans. These results suggest a novel mechanism in the development of orthostatic intolerance in humans.

Keywords: blood pressure, autonomic nervous system, muscle sympathetic nerve activity, hypotension

orthostatic intolerance (OI) is the inability to maintain blood pressure and cerebral perfusion while in the upright position. Moreover, the failure to maintain blood pressure in the upright posture is associated with increased mortality (26). Head-down bed rest (BR) is used to simulate microgravity and physical deconditioning and to elicit OI (13). Mechanisms believed to contribute to the development of OI with BR include: impaired vagal baroreflex responses (5), an inadequate increase in sympathetic discharge (18, 42), cardiac atrophy (24), an inability to increase peripheral vascular resistance (3, 25), and hypovolemia (29). Studies indicate that alterations in sympathetic nerve activity contribute to the development of OI (13, 18, 25, 42). Hypotensive episodes during head-up tilt appear to be closely related to lack of increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) (25). MSNA is attenuated during tilt following 14 days of BR in subjects that experienced OI (42). Despite considerable research on this topic, the mechanisms for OI have been an enigma. One possible mechanism for the development of OI after BR that has not been examined is an alteration of the vestibulosympathetic reflex (VSR).

Data exist demonstrating the presence of a vestibular-mediated sympathetic reflex that contributes to blood pressure regulation in both humans and animals (8, 15, 19, 43, 49, 50). Bilateral transection of the vestibular nerve results in persistent hypotension during upright tilt in the cat (8). Additionally, direct electrical stimulation of the vestibular nerve elicits sympathetic nerve activation and increased vascular resistance in the cat (21, 22, 48, 50). In humans, using head-down rotation (HDR) as a model to activate the vestibular otolith organs, we have demonstrated marked increases in MSNA and peripheral vasoconstriction (15, 31, 33–35, 43). Other studies have supported the presence of the VSR in humans (1, 12, 19, 46). Studies examining changes to the vestibular system after BR are sparse. Altered nystagmus patterns indicating changes in vestibular function have been observed after 7 days of BR (4). However, currently no studies have examined whether the VSR is altered after BR.

The purpose of this study was to examine the VSR and OI after short-duration and prolonged 6° head-down BR. It was hypothesized that the MSNA response to HDR would be attenuated after prolonged BR and would be associated with reductions in orthostatic tolerance. Additionally, there would be no relation between the VSR and orthostatic tolerance after short-term BR because the lack of adequate time to elicit functional changes in the vestibular system.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine and the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas (study 2), approved all experiments, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before testing.

Experimental design.

Two studies were performed. One study consisted of 24-h BR conducted at the General Clinical Research Center at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, PA. The second study consisted of prolonged BR (36 ± 1 days) and was conducted in association with the University of Texas Medical Branch Flight Analogs Research Center, in Galveston, TX. All experiments were performed in a dimly lit, quiet laboratory maintained at 21–23°C.

HDR.

Both studies used vestibular otolith activation before and after BR. Subjects performed HDR in the prone position to engage the otolith organs as described previously (43). This maneuver, however, does not engage the semicircular canals when the head becomes stationary. Previous studies have eliminated other possible factors (such as neck afferents, baroreceptors, central command, and visual inputs) contributing to sympathetic activation during HDR (15, 30, 31, 33, 43). After a 3-min baseline period with the head in the chin-up neck-extended position, the chin support was removed and the head was passively rotated to the point of maximal rotation. This position was maintained for 3 min followed by the subject's head being passively returned to the chin-up neck-extended position for 3 min of recovery. During the head movements, continuous blood pressure measurements, heart rate, MSNA, and limb blood flow of the contralateral leg were recorded.

Head-up tilt.

All subjects underwent a head-up tilt (HUT) test at 80° for up to 30 min to assess their orthostatic tolerance before and after BR. HUT was performed during pretesting, after 24-h BR, and either at 45 days (n = 3) or 60 days (n = 4) of BR. The tilt test was terminated for any of the following reasons: if the subject completed 30 min of HUT, the subjects began to feel presyncopal symptoms including lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, excessive heat, or sweating, the subjects′ systolic blood pressure decreased >25 mmHg or below 70 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure decreased >15 mmHg. Arterial blood pressure and heart rate were monitored continuously during HUT.

24-h BR.

Twenty-two young healthy volunteers (12 men and 10 women; age, 24 ± 1 years; height, 174.4 ± 2.6 cm; weight, 71.7 ± 3.4 kg) participated in the study. All subjects were nonsmokers, nonobese, normotensive, and not taking any medications that would influence the results of the study.

Subjects abstained from caffeine (12 h) before and during the study. Subjects performed HDR and HUT as described above. After the HUT protocol, the instrumentation was removed and subjects were placed at 6° head-down BR for 24 h. During this time, subjects were not allowed to sit up or get out of bed. Their sleep schedule was maintained to what they received the night before testing. After 24 h, the subjects were brought back into the testing room to undergo the same experimental protocol as before BR. During post-testing, the subjects did not sit up or get out of BR during this time, but were brought back up to the zero-degree level and instrumented for the HDR protocol.

Prolonged BR.

Eight healthy volunteers (5 men and 3 women; age, 26–44 years; height, 155.2–170.9 cm; weight, 43.8–90.8 kg) participated in the study. A suitable nerve signal could not be obtained in one subject and was excluded from the MSNA analysis. Popliteal blood flow data was not successfully obtained in a different subject and was excluded from blood flow analysis. All subjects were nonsmokers and in good health with no history of cardiovascular, neurological, gastrointestinal, or musculoskeletal problems.

This study was part of a 115- to 119-day BR study conducted at the University of Texas Medical Branch Flight Analogs Research Center in Galveston, TX, sponsored by NASA. The subjects were tested ∼6 ± 1 days before BR and underwent HDR protocol and HUT as described in the 24-h BR study. After the pretest period, the subjects were placed in 6° head-down BR for 90 days. Participants lived in a special research unit for the entire study and were fed a carefully controlled diet. Every day, they were awake for 16 h and asleep (lights out) for 8 h. During the BR time, they participated in a number of other tests run by a variety of researchers. Subjects repeated the HDR protocol at 36 ± 1 days of BR. Three subjects repeated the protocol again at 75 ± 1 days of BR. In addition, the subjects performed HUT at 45 days (n = 3) or 60 days (n = 4) of BR.

Measurements.

Microneurography was used to assess MSNA as described previously (43). Briefly, multifiber recordings of MSNA were obtained from a tungsten microelectrode inserted in the peroneal nerve behind the knee. A reference electrode was placed subcutaneously 2 to 3 cm from the recording electrode. Previously identified criteria for an adequate MSNA signal were applied to ensure proper recording (44). The nerve signal was amplified (20,000–40,000 times), fed though a bandpass filter with a band width of 700–2,000 Hz, integrated using a 0.1-s time constant (University of Iowa Bioengineering, Iowa City, IA), and recorded digitally (16SP Powerlab; ADInstruments, New Castle, Australia). The mean voltage neurogram was routed to a computer screen and a loudspeaker for monitoring during the study. Sympathetic recordings that demonstrated possible electrode site shifts, altered respiratory patterns (e.g., breath holding, inspiratory gasp, and hyperventilation), or electromyographic artifact during experimental intervention were excluded from analysis.

Leg blood flow was assessed in two ways. Venous occlusion plethysmography (Hokanson EC 4 plethysmograph, D.E. Hokanson, Bellevue, WA) was used to assess calf blood flow of the contralateral leg (24 h BR), as described previously (15), and Doppler ultrasound (Phillips Medical Systems, iU22, with a 5–12 MHz linear probe) was used to assess popliteal blood flow (prolonged BR). Calf vascular conductance was calculated as the ratio of limb blood flow to mean arterial pressure. Popliteal blood flow was determined by mean blood velocity and diameter of the vessel. Leg vascular conductance was calculated as the ratio of popliteal blood flow to mean arterial pressure.

Heart rate was derived from an ECG. Arterial blood pressure was measured continuously by a finger photoplethysmography (Finapres, Ohmeda, Englewood, CO) during each trial. Respiration pattern was monitored using impedance plethysmography.

Data analysis.

All data were digitally recorded at 100 Hz for later offline analysis. MSNA was expressed as bursts per minute and total activity (sum of the area of each individual burst expressed in arbitrary units). Neurograms were normalized using the highest burst amplitude set to 1,000 and the baseline set to zero. Sympathetic bursts were identified from the mean voltage neurogram by visual inspection with a computer program (Chart 5; ADInstruments).

Statistics.

To identify possible differences within each BR trial, a two-way (BR, intervention) repeated-measures ANOVA was used. Tests for simple effects were used to identify differences in baseline (20). MSNA responses to HDR were made between the average resting (baseline) value and the first minute of HDR. Data from three subjects at day 75 was not used in the statistical analysis. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used for all tests. Values are presented as mean ± SE.

RESULTS

24-h BR.

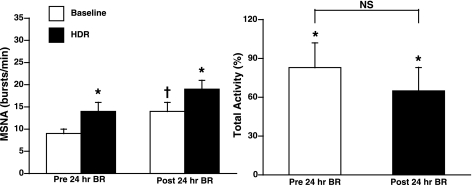

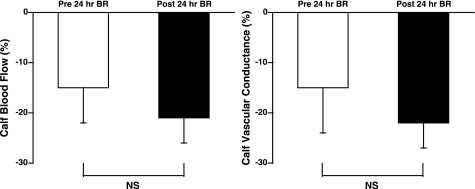

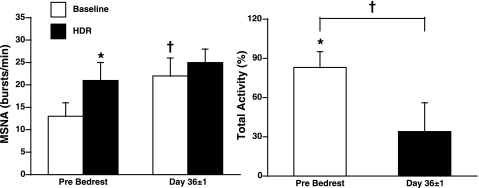

The effect of 24-h BR on MSNA responses to the VSR activation is shown in Fig. 1. Before BR, MSNA significantly increased during HDR in both burst frequency (9 ± 1 to 14 ± 2 bursts/min, Δ5 ± 1 bursts/min; P < 0.001; n = 22) and total activity (Δ83 ± 19%; P < 0.001). After BR, MSNA at rest significantly increased (14 ± 2 bursts/min; P < 0.001). Despite elevated baseline MSNA at rest, HDR significantly increased MSNA in both burst frequency (19 ± 2 bursts/min, Δ5 ± 1 bursts/min; P < 0.001) and total activity (Δ65 ± 18% total activity; P < 0.002). Thus there were no significant differences in the MSNA response to HDR before and after 24-h BR (Fig. 1). Individual MSNA responses to HDR are presented in Fig. 2 (left). Mean arterial pressure and heart rate did not change significantly with HDR and were not significantly different before and after BR (Table 1). Venous occlusion plethysmography was used to measure calf blood flow in eight subjects, and the results are presented in Fig. 3. Calf vascular conductance decreased both before and after BR (Δ15 ± 9 and Δ 22 ± 5%, respectively; P < 0.05) during HDR. There was no significant difference in calf vascular conductance before and after BR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) burst frequency (in bursts per minute) and change in total activity (in percentage) during head-down rotation (HDR) before and after 24-h bed rest (BR). Burst frequency significantly increased during HDR both before and after BR. Baseline MSNA was significantly increased following BR. The change in total activity was significantly increased during HDR, but was not significantly different from before BR. *P < 0.001 compared with baseline; †P < 0.01 compared with before BR; NS, not significant.

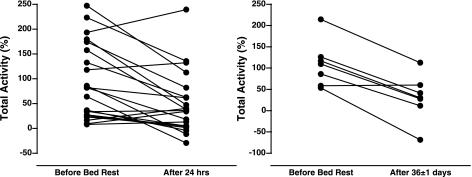

Fig. 2.

Individual responses for change in MSNA (total activity) during HDR following 24-h and 36-day BR. Fifteen subjects decreased and 7 subjects increased their change in MSNA (total activity) during HDR after 24-h BR. Also, 6 subjects decreased and 1 subject had no change in MSNA (total activity) during HDR following prolonged BR.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic responses to HDR following BR

|

Study 1 |

Study 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Pre-24-h BR | Post-24-h BR | Pre-BR | Day 36 ± 1 BR |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | ||||

| Baseline | 87 ± 3 | 90 ± 4 | 101 ± 4 | 94 ± 5* |

| HDR | 88 ± 1 | 90 ± 4 | 101 ± 4 | 94 ± 5 |

| ΔBaseline vs. HDR | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | ||||

| Baseline | 57 ± 2 | 61 ± 2 | 68 ± 5 | 73 ± 4 |

| HDR | 60 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 | 70 ± 5 | 78 ± 4 |

| ΔBaseline vs. HDR | 3 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 5 ± 1† |

Values are means ± SE. There were no significant differences between before and after 24-h bed rest (BR). HDR, head-down rotation.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001 compared with pre-BR value.

Fig. 3.

Change in calf blood flow (in percentage) and calf vascular conductance [in percentage, blood flow/mean arterial pressure (MAP)] during HDR before and after 24 h BR. Both blood flow and calf vascular conductance significantly decreased during HDR both before and after BR (P < 0.05). Flow and conductance were not significantly different after BR.

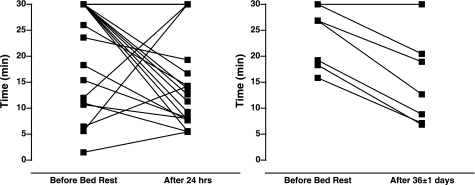

HUT duration before and after BR is shown in Fig. 4 (left). Thirteen subjects decreased, four subjects increased, and five subjects had no change in tilt time after BR. We observed no relation between VSR activation and altered orthostatic intolerance before and after 24-h BR.

Fig. 4.

Individual responses for head-up tilt duration after 24-h and prolonged BR. Thirteen subjects decreased, 4 subjects increased, and 5 subjects had no change in tilt time from before to after 24-h BR. Six subjects decreased, whereas only 1 subject had no change in tilt time from before to after 36-days BR.

Prolonged BR.

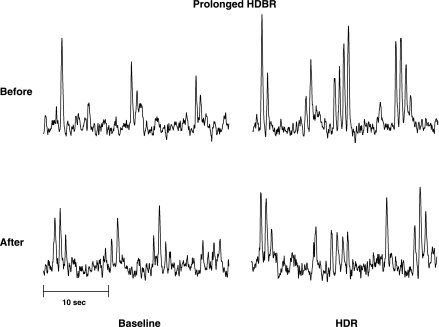

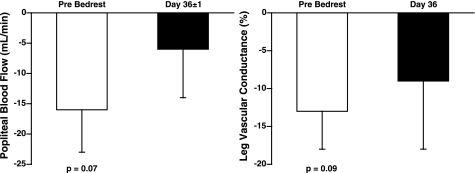

Figure 5 is a representative neurogram of the MSNA response to HDR before and after prolonged BR in one subject. Before BR, MSNA significantly increased in both burst frequency (13 ± 3 to 21 ± 4 burst/min, Δ8 ± 2 bursts/min; P < 0.05; n = 7) and total activity (Δ83 ± 12%; P < 0.01) during HDR (Fig. 6). At 36 ± 1 days of BR, the baseline MSNA at rest was increased from 13 ± 3 to 22 ± 4 bursts/min (P < 0.05). Unlike 24-h BR, prolonged BR attenuated the MSNA responses to HDR. MSNA was not significantly increased with HDR in either burst frequency (Δ3 ± 2 bursts/min, Δ23 ± 13%) or total activity (Δ34 ± 22%) after prolonged BR (Fig. 6). Individual MSNA responses are presented in Fig. 2 (right). Six subjects had an attenuated MSNA response to HDR after BR, whereas one subject demonstrated no change in MSNA response to HDR. Additionally, three subjects were tested again at 75 ± 1 days of BR. Baseline MSNA at rest increased further from 22 ± 4 bursts/min at day 36 to 29 ± 8 bursts/min at day 75. The increase in MSNA to HDR remained attenuated in these subjects (Δ23 ± 13% bursts/min). Before BR, mean arterial pressure and heart rate did not significantly change during HDR (Table 1). Following prolonged BR, mean arterial pressure at rest decreased from 101 ± 4 to 94 ± 5 mmHg (P < 0.001), but did not significantly change during HDR. Baseline heart rate increased (68 ± 5 to 73 ± 4 beats/min; P < 0.01) and was significantly increased with HDR (Δ5 ± 1 beats/min; Table 1) after BR. Before BR, Doppler ultrasound of the popliteal artery demonstrated a tendency to decrease popliteal blood flow (117 ± 32 to 101 ± 27 ml/min; P = 0.07) and popliteal vascular conductance (Δ13 ± 5%; P = 0.09) during HDR (Fig. 7). At 36 ± 1 days of BR, baseline popliteal blood flow at rest tended to be decreased (100 ± 17 ml/min; P = 0.06). However, popliteal blood flow and vascular conductance did not significantly decrease during HDR (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

Representative neurogram of 1 test subject before and after 36 days of BR. Baseline MSNA at rest was increased after BR. MSNA increased significantly during HDR before BR (HDBR), but at 36 days, the increase in MSNA was attenuated.

Fig. 6.

MSNA burst frequency (in bursts per minute) and change in total activity (in percentage) during HDR before and after prolonged BR. MSNA significantly increased during HDR before BR. Baseline MSNA was significantly increased after BR. MSNA was not significantly increased during HDR at 36 ± 1 days. *P < 0.05 compared with baseline; †P < 0.05 compared with before BR.

Fig. 7.

Change in popliteal blood flow and leg vascular conductance (in percentage; blood flow/MAP) during HDR before and after prolonged BR. Blood flow and vascular conductance tended to decrease before BR (P = 0.07, P = 0.09, respectively).

HUT duration before and after BR is shown for individual subjects in Fig. 4 (right). Six subjects decreased, whereas one subject had no change in tilt time after BR.

DISCUSSION

The major finding from this study was that prolonged BR attenuated the VSR. These results suggest a desensitization of the VSR occurs after prolonged BR deconditioning. This physiological adaptation may serve as a contributory mechanism for the development of OI after physical deconditioning and spaceflight.

Subjects performed HUT to assess orthostatic tolerance. After the 24-h BR, some of the subjects decreased tilt time, whereas other subjects demonstrated an increase or no change in tilt time. There was no clear relation between the change in tilt time and the sensitivity of the VSR after 24-h BR in our subjects. However, during prolonged BR nearly all subjects had a reduction in tilt time and an attenuated VSR. Additionally, the VSR remained attenuated in three subjects tested again at 75 ± 1 days of BR. These results could suggest that over time during BR, the VSR might be a contributing factor in the development of orthostatic hypotension.

The increase in MSNA during HDR before BR is consistent with our previous findings (15, 32, 43). Despite the increased baseline MSNA at rest after 24-h BR, HDR increased MSNA to the same extent as before BR, indicating an intact VSR. In contrast, after prolonged BR the increase in MSNA to HDR was significantly attenuated. This observation suggests a clear reduction in the sensitivity of the VSR. The mechanism(s) by which these changes occur is unknown. However, a possible mechanism to explain the change in the VSR with BR could be due to changes in the sensitivity of the vestibular apparatus through a possible fluid shift in the inner ear. Recently, our laboratory has demonstrated that dehydration by glycerol attenuates the VSR (10). A similar fluid shift elicited by hypovolemia experienced during BR might contribute to the attenuated VSR during prolonged BR. Additionally, desensitization of the VSR could occur with prolonged BR through structural hair cell changes, which has been reported to occur with aging (2, 11, 37) and microgravity (6). We have reported that older subjects have marked attenuation in the VSR (36) and experience an increase in orthostatic intolerance (40). Thus structural changes of the VSR could be a common mechanism explaining increased OI observed with BR deconditioning and with aging. Other explanations could include altered integration between the baroreflexes and the VSR (9, 14, 31), changes in the central processing of vestibular inputs (16, 49), or possible alterations in the excitability of the various neural pathways that regulate sympathetic activity.

Some studies have suggested a correlation between OI and changes in vestibular function after spaceflight (36, 47, 49). Kamiya et al. (18) demonstrated a paradoxical sympathetic withdrawal with less of an increase in MSNA during upright tilt in subjects that experience OI after 14 days BR. An altered VSR could explain the attenuated increase in MSNA observed in their study. Microgravity has been demonstrated to elicit marked changes in the vestibular system with at least 50% of astronauts experiencing space motion sickness in the first few days (7) and altered otolith-ocular and otolith-spinal reflexes (27). Both morphological and physiological changes to the vestibular system have been demonstrated after spaceflight (6, 28, 38, 39, 45). Most changes to the vestibular system as a result of microgravity impact the otolith organs because they are dependent on gravitational inputs (7, 27, 49). Because the VSR is an otolith-mediated reflex (19, 35), it is reasonable to hypothesize that the changes observed during BR could apply to microgravity and contribute to post-spaceflight OI, which occurs in nearly two-thirds of all astronauts (3).

A secondary observation from this study is that baseline MSNA at rest was elevated rapidly by 1 day of BR (study 1). Previous studies investigating baseline MSNA at rest after BR have revealed equivocal results. Both increases (17, 29) and decreases (41) in baseline MSNA at rest have been reported. Our results indicate an increase in baseline MSNA after both 24-h and prolonged BR similar to previous reports (17). Elevated MSNA at rest has also been reported in spaceflight (23). These results are consistent with the concept that MSNA at rest should increase as a result of reduced cardiac filling pressures and central blood volume that is associated with prolonged BR (13, 24).

It could be suggested that the elevated MSNA at rest after prolonged BR prevented a further increase in MSNA during HDR. However, indicators suggest otherwise. First, all subjects demonstrated a robust sympathetic response to apnea following BR (data not presented). This indicates that sympathetic activity could be increased further than what was observed during HDR after prolonged BR and was not limited by the elevation in MSNA at rest. Second, in three subjects where MSNA measurements were taken at both day 36 and day 75 of BR there was a clear elevation in MSNA at rest (from ∼22 to 29 bursts/min, respectively). However, despite this further increase in MSNA at rest, MSNA responses to HDR were still comparable. If the elevated baseline MSNA contributed in limiting the sympathetic responses to HDR, MSNA would have been expected to increase less at day 75. However, this was not the case.

Changes in peripheral vascular conductance observed in these studies correspond with changes in MSNA. Other studies have noted reduced peripheral vascular responses after BR (13, 18). In our study, elevated sympathetic activation at rest could affect the sensitivity and responsiveness of the vasculature. However, this does not appear to be the case after short-duration BR because HDR elicited comparable increases in MSNA with corresponding reductions in calf vascular conductance despite elevated MSNA. In contrast, after prolonged BR the sensitivity of the vasculature could be altered. Our data demonstrate a relation between diminished MSNA and vasculature responses to HDR following prolonged BR. Therefore, an attenuation of the VSR could contribute to inadequate increases in limb vasoconstriction and contribute to subsequent decreases in orthostatic tolerance.

HDR protocols and HUT were not performed on the same day during the prolonged BR study. We do not believe this limitation adversely affects our interpretation of the results because the data were reproducible at 75 days in three of the subjects. Additionally, it is difficult to quantify the stimulus to the otolith organs that HDR elicits. However, to minimize this concern, repeated HDR maneuvers were performed to the same degree of head rotation within subjects. Therefore, we believe we elicited comparable stimulation of the VSR before and after BR. Finally, it is recognized that a time control group was not a part of this study. The original plan of this project was to retest the subjects after they were again mobile and rehabilitated. However, Hurricane Rita caused a premature stoppage of this project and prevented us from retesting these subjects.

Summary.

This study demonstrates that prolonged BR (∼ 5 wk) unlike short-term BR (24 h) attenuates the VSR. This attenuation in the VSR was associated with reduced orthostatic tolerance. These results could suggest a novel mechanism that might contribute to the development of OI.

GRANTS

This project was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-077670 and DC-006459), National Space Biomedical Research Institute (CA00404), and the American Heart Association.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.J.D. and C.A.R. performed experiments; D.J.D., C.L.S., and C.A.R. analyzed data; D.J.D. and C.L.S. prepared figures; D.J.D., C.L.S., and C.A.R. drafted manuscript; D.J.D., C.L.S., and C.A.R. approved final version of manuscript; C.L.S. and C.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; C.A.R. conception and design of research; C.A.R. interpreted results of experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the laboratory personnel for assistance and the support of staff and nurses provided by the General Clinical Research Center at Pennsylvania State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA (MO1RR10732) and the University of Texas Medical Branch Flight Analogs Research Center (M01RR000073).

REFERENCES

- 1. Bent LR, Bolton PS, Macefield VG. Modulation of muscle sympathetic bursts by sinusoidal galvanic vestibular stimulation in human subjects. Exp Brain Res 174: 701–711, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergstrom B. Morphology of the vestibular nerve. II. The number of myelinated vestibular nerve fibers in man at various ages. Acta Otolaryngol 76: 173–179, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buckey JC, Jr, Lane LD, Levine BD, Watenpaugh DE, Wright SJ, Moore WE, Gaffney FA, Blomqvist CG. Orthostatic intolerance after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81: 7–18, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burgeat M, Toupet M, Loth D, Ingster I, Guell A, Coll J. Status of vestibular function after prolonged bedrest. Acta Astronaut 8: 1019–1027, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Eckberg DL, Fritsch JM, Vernikos-Danellis J. Head-down bed rest impairs vagal baroreflex responses and provokes orthostatic hypotension. J Appl Physiol 68: 1458–1464, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daunton NG. Adaptation of the vestibular system to microgravity. In: Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Enviromental Physiology edited by Fregely MJB C. M.New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 765–783 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daunton NG. Adaptation of the vestibular system to microgravity. In: Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Enviromental Physiology edited by Fregely MJB. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 765–783 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doba N, Reis DJ. Role of the cerebellum and the vestibular apparatus in regulation of orthostatic reflexes in the cat. Circ Res 40: 9–18, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dyckman DJ, Monahan KD, Ray CA. Effect of baroreflex loading on the responsiveness of the vestibulosympathetic reflex in humans. J Appl Physiol 103: 1001–1006, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dyckman DJ, Sauder CL, Ray CA. Glycerol-induced fluid shifts attenuate the vestibulosympathetic reflex in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R630–R634, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Engstrom H, Ades HW, Engstrom B, Gilchrist D, Bourne G. Structural changes in the vestibular epithelia in elderly monkeys and humans. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 22: 93–110, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Essandoh LK, Duprez DA, Shepherd JT. Reflex constriction of human limb resistance vessels to head-down neck flexion. J Appl Physiol 64: 767–770, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fortney SM, Schneider VS, Greenleaf JE. The physiology of bed rest. In: Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Enviromental Physiology, edited by Fregely MJB. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 889–939 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gotoh TM, Fujiki N, Matsuda T, Gao S, Morita H. Roles of baroreflex and vestibulosympathetic reflex in controlling arterial blood pressure during gravitational stress in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R25–R30, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hume KM, Ray CA. Sympathetic responses to head-down rotations in humans. J Appl Physiol 86: 1971–1976, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jarchow T, Young LR. Neurovestibular effects of bed rest and centrifugation. J Vestib Res 20: 45–51, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamiya A, Iwase S, Kitazawa H, Mano T. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) after 120 days of 6 degrees head-down bed rest (HDBR). Environ Med 43: 150–152, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kamiya A, Michikami D, Fu Q, Iwase S, Hayano J, Kawada T, Mano T, Sunagawa K. Pathophysiology of orthostatic hypotension after bed rest: paradoxical sympathetic withdrawal. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1158–H1167, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaufmann H, Biaggioni I, Voustianiouk A, Diedrich A, Costa F, Clarke R, Gizzi M, Raphan T, Cohen B. Vestibular control of sympathetic activity. An otolith-sympathetic reflex in humans. Exp Brain Res 143: 463–469, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keppel G. Design and Analysis: A Researcher's Handbook. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kerman IA, McAllen RM, Yates BJ. Patterning of sympathetic nerve activity in response to vestibular stimulation. Brain Res Bull 53: 11–16, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerman IA, Yates BJ. Regional and functional differences in the distribution of vestibulosympathetic reflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R824–R835, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levine BD, Pawelczyk JA, Ertl AC, Cox JF, Zuckerman JH, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Ray CA, Smith ML, Iwase S, Saito M, Sugiyama Y, Mano T, Zhang R, Iwasaki K, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Jr, Cooke WH, Baisch FJ, Eckberg DL, Blomqvist CG. Human muscle sympathetic neural and haemodynamic responses to tilt following spaceflight. J Physiol 538: 331–340, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levine BD, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA. Cardiac atrophy after bed-rest deconditioning: a nonneural mechanism for orthostatic intolerance. Circulation 96: 517–525, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mano T, Iwase S. Sympathetic nerve activity in hypotension and orthostatic intolerance. Acta Physiol Scand 177: 359–365, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Masaki KH, Schatz IJ, Burchfiel CM, Sharp DS, Chiu D, Foley D, Curb JD. Orthostatic hypotension predicts mortality in elderly men: the Honolulu Heart Program. Circulation 98: 2290–2295, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moore ST, Clement G, Dai M, Raphan T, Solomon D, Cohen B. Ocular and perceptual responses to linear acceleration in microgravity: alterations in otolith function on the COSMOS and Neurolab flights. J Vestib Res 13: 377–393, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parker DE. Human vestibular function and weightlessness. J Clin Pharmacol 31: 904–910, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pawelczyk JA, Zuckerman JH, Blomqvist CG, Levine BD. Regulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity after bed rest deconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2230–H2239, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ray CA. Interaction between vestibulosympathetic and skeletal muscle reflexes on sympathetic activity in humans. J Appl Physiol 90: 242–247, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ray CA. Interaction of the vestibular system and baroreflexes on sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2399–H2404, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ray CA, Carter JR. Vestibular activation of sympathetic nerve activity. Acta Physiol Scand 177: 313–319, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ray CA, Hume KM. Neck afferents and muscle sympathetic activity in humans: implications for the vestibulosympathetic reflex. J Appl Physiol 84: 450–453, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ray CA, Hume KM, Shortt TL. Skin sympathetic outflow during head-down neck flexion in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1142–R1146, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ray CA, Hume KM, Steele SL. Sympathetic nerve activity during natural stimulation of horizontal semicircular canals in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1274–R1278, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ray CA, Monahan KD. Aging attenuates the vestibulosympathetic reflex in humans. Circulation 105: 956–961, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosenhall U, Rubin W. Degenerative changes in the human vestibular sensory epithelia. Acta Otolaryngol 79: 67–80, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ross MD. Morphological changes in rat vestibular system following weightlessness. J Vestib Res 3: 241–251, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ross MD. A spaceflight study of synaptic plasticity in adult rat vestibular maculas. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh) 516: 1–14, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rutan GH, Hermanson B, Bild DE, Kittner SJ, LaBaw F, Tell GS. Orthostatic hypotension in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Hypertension 19: 508–519, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shoemaker JK, Hogeman CS, Leuenberger UA, Herr MD, Gray K, Silber DH, Sinoway LI. Sympathetic discharge and vascular resistance after bed rest. J Appl Physiol 84: 612–617, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shoemaker JK, Hogeman CS, Sinoway LI. Contributions of MSNA and stroke volume to orthostatic intolerance following bed rest. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R1084–R1090, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shortt TL, Ray CA. Sympathetic and vascular responses to head-down neck flexion in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1780–H1784, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjork HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev 59: 919–957, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. vonBaumgarten RJ. European vestibular experiments on the Spacelab-1 mission: 1. Overview. Exp Brain Res 64: 239–246, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Voustianiouk A, Kaufmann H, Diedrich A, Raphan T, Biaggioni I, Macdougall H, Ogorodnikov D, Cohen B. Electrical activation of the human vestibulo-sympathetic reflex. Exp Brain Res 171: 251–261, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watenpaugh DE, Hargens AR. The cardiovascular system in microgravity. In: Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Enviromental Physiology, edited by Fregely MJB. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 631–674 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yates BJ. Vestibular influences on the autonomic nervous system. Ann N Y Acad Sci 781: 458–473, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yates BJ, Kerman IA. Post-spaceflight orthostatic intolerance: possible relationship to microgravity-induced plasticity in the vestibular system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 28: 73–82, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yates BJ, Miller AD. Physiological evidence that the vestibular system participates in autonomic and respiratory control. J Vestib Res 8: 17–25, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]