Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) may play an important role in tumor immunity. We studied the activation state of TAMs in cutaneous SCC, the second most common human cancer. CD163 was identified as a more abundant, sensitive, and accurate marker of TAMs, compared to CD68. CD163+ TAMs produced pro-tumoral factors MMP9 and MMP11, at the gene and protein levels. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to evaluate M1 and M2 macrophage gene sets in the SCC genes and to identify candidate genes in order to phenotypically characterize TAMs. There was co-expression of CD163 and alternatively activated “M2” markers, CD209 and CCL18. There was enrichment for classically activated “M1” genes in SCC, which was confirmed in situ by co-localization of CD163 and phosphorylated STAT1, IL-23p19, IL-12/IL-23p40, and CD127. Also, a subset of TAMs in SCC was bi-activated as CD163+ cells expressed markers for both M1 and M2, shown by triple-label immunofluorescence. These data support heterogeneous activation states of TAMs in SCC, and suggest that a dynamic model of macrophage activation would be more useful to characterize TAMs.

Keywords: cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, CD163, macrophages, skin

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common human cancer, affecting more than 300,000 individuals in the United States annually (Brantsch et al., 2008; Weinberg et al., 2007). Although most cases can be treated successfully by surgical removal, certain aggressive cases can cause extensive tissue destruction and metastasize to local lymph nodes and distant organs. These aggressive cases are responsible for approximately 10,000 non-melanoma skin cancer deaths in the US each year. Aggressive behavior by SCC is observed in solid organ transplant recipients (Carucci, 2004). Based on the potential for the host immunity to regulate tumor behavior in SCC, it is important to characterize the tumor-associated immune microenvironment.

Macrophages are one of the major populations of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes associated with solid tumors (Gordon and Taylor, 2005). Macrophages that infiltrate and surround tumor nodules are defined as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (Wang et al., 2010), and different studies have shown that macrophages may either inhibit or stimulate tumor growth. Initially, TAMs were shown to participate in the early eradication of tumor cells in vitro (Romieu-Mourez et al., 2006). However, other studies have suggested that TAMs may contribute to carcinogenesis, as there is a positive correlation between increased numbers of TAMs and poor prognosis in some human cancers (Bingle et al., 2002; El-Rouby, 2010; Leek et al., 1996; Lin and Pollard, 2007; Nonomura et al., 2010; Shabo et al., 2008; Sica et al., 2006; Steidl et al., 2010). TAMs can fail to recognize tumor antigens (Fadok et al., 1998) and may release factors that directly stimulate tumor growth and angiogenesis (Lin et al., 2006; Lin and Pollard, 2007). Furthermore, the tumor itself can create a dynamic microenvironment that can transform TAMs (Gocheva et al., 2010). Thus, TAMs in the SCC microenvironment may be associated with tumor growth.

Currently, the general classification of macrophage activation parallels the Th1/Th2 paradigm, defining classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) cells (Mantovani et al., 2004; Mosser and Edwards, 2008). Classically activated macrophages are induced by IFNγ and have a high capacity to present antigen. Alternatively activated macrophages are induced by the cytokine IL-4, which promotes Type 2 responses. As SCCs usually progress, in association with a Th2 microenvironment and low levels of IFNγ, it is thought that the net immune response is ineffective at suppressing tumor growth. Hence, TAMs have commonly been considered alternatively activated or strongly skewed to the M2 phenotype (Biswas et al., 2006; Gordon and Martinez, 2010; Martinez et al., 2009; Siveen and Kuttan, 2009). However, there has been renewed debate over the phenotypic activation of TAMs as the physiology of these macrophages has been shown to change over time and to demonstrate remarkable plasticity (Mosser and Edwards, 2008).

Given the importance of TAMs contributing to tumor growth, and the current conflicting state of the understanding of TAM activation, we set out to phenotypically characterize macrophages in SCC. Initially, we used a non-biased genomic approach to guide our choice of markers to further evaluate TAMs. “M1” and “M2” activated macrophage gene sets (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010) were analyzed in our SCC genomic phenotype (Haider et al., 2006) using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Bluth et al., 2009; Subramanian et al., 2005). We then identified candidate genes that were expressed in the macrophage and SCC gene sets and performed immunofluorescence on SCCs versus CD163, as our constitutive macrophage marker.

Previously, we have shown that in normal skin and psoriasis, CD163 is the most useful marker of dermal macrophages (Zaba et al., 2007). We expanded on that work to characterize tumor-associated macrophages in human SCC. We found the following: (1) Compared to CD68, CD163 was a more abundant, sensitive, and accurate marker of TAMs; (2) There was an increase in the pro-tumoral factors MMP9 and MMP11 in SCC, and CD163+ TAMs produced MMP9 and MMP11; (3) There was co-expression of CD163 and alternatively activated “M2” markers, CD209 and CCL18; (4) There was enrichment for classically activated “M1” genes in SCC, which was confirmed in situ by co-localization of CD163 and phosphorylated STAT1, IL-23p19, IL-12/IL-23p40, and CD127; and (5) A subset of TAMs in SCC was bi-activated as CD163+ cells expressed markers for both M1 and M2, shown by triple-label immunofluorescence. These data support heterogeneous activation states of TAMs in SCC, and suggest that a dynamic model of macrophage activation would be more useful to characterize TAMs. Furthermore, driving TAM activation toward a more dominant anti-cancer phenotype might be a potential therapeutic strategy.

RESULTS

Macrophages were more abundant in SCC compared to normal skin

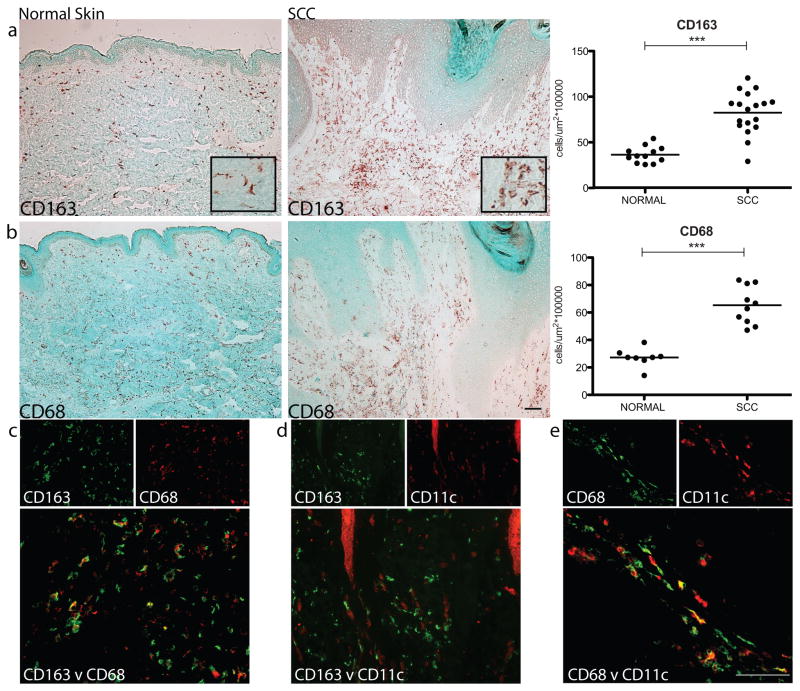

Macrophages were quantified in SCC and normal skin (n= 8–18) using CD163, which we consider a reliable marker of macrophages in normal skin and psoriasis, and CD68, the widely accepted macrophage marker (Bluth et al., 2009; Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010; Zaba et al., 2007). Representative immunohistochemistry is shown for CD163 and CD68, and cell counts of the cases are presented (Figure 1a–b). The vast majority of CD163+ and CD68+ macrophages were surrounding, rather than infiltrating, the SCC tumor nests, and both CD163+ and CD68+ macrophages were significantly increased, approximately two-fold, in SCC compared to normal skin (p<0.001 for both). Additionally, using double-label immunofluorescence, CD163 co-localized with CD68 but there were CD163+ cells that did not co-express CD68, suggesting that CD163 is a more robust and sensitive marker of macrophages in the skin than CD68 (Figure 1c). We also evaluated the co-expression of CD163 with the well-known dendritic cell (DC) marker, CD11c (Bluth et al., 2009). As we have previously shown in normal skin (Zaba et al., 2007), CD163+ cells in SCC also did not co-localize with this DC marker (Figure 1d), demonstrating that these are two distinct leukocyte populations. In contrast, CD68+ cells close to SCC tumor nests did show co-localization with CD11c (Figure 1e).

Figure 1. Macrophages were more abundant in SCC compared to normal skin.

Representative immunohistochemistry (10x) and cell counts of the macrophage markers (a) CD163 (with an inset of CD163+ cells at 20x) and (b) CD68, showing a significantly increased number of macrophages surrounding SCC tumor nests compared to normal skin. Each dot represents one patient. ***P <0.001. (c) CD163 (green) co-localized with CD68 (red) shown as yellow, but there were CD163+ cells that did not co-express CD68. (d) CD163 (green) did not co-express CD11c (red), while (e) some CD68+ cells (green) did co-express CD11c (red) shown as yellow. Bar=100μm.

SCC TAMs expressed pro-tumoral products in the tumor microenvironment

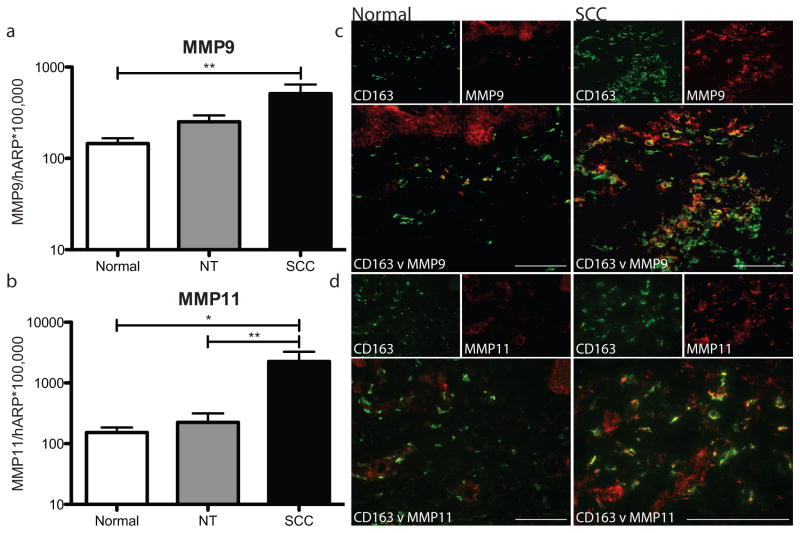

TAMs may produce factors that encourage tumorigenesis. We have shown SCC TAMs produce the pro-lymphangiogenic factor VEGF-C, which favors tumor growth and development (Moussai et al., 2011). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that may contribute to tumor invasion by degrading the matrix surrounding tumor nodules, may also be produced by TAMs in SCC. MMP1, MMP10 and MMP13 genes have been shown to be upregulated in SCC (Haider et al., 2006). MMP9 (gelatinase B) and MMP11 (stromelysin-3) proteins correlate with increased tumor aggressiveness (Buergy et al., 2009; Pinto et al., 2003; Shah et al., 2010; Steidl et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010). Neither MMP9 nor MMP11 have been classified as products representative of either state of macrophage activation. We showed that there was increased gene expression by RT-PCR of MMP9 in SCC compared to adjacent non-tumoral skin and normal skin (p=0.07 and 0.008, respectively) (Figure 2a). Similarly, MMP11 was also increased in SCC compared to adjacent non-tumoral skin and normal skin (p=0.003 and 0.025, respectively) (Figure 2b). We then asked whether TAMs could be a possible source of the increased MMP9 and MMP11. There was abundant co-localization of MMP9 and MMP11 with CD163+ macrophages in SCCs compared to normal skin (Figure 2c–d). These findings suggest that TAMs secrete pro-tumoral products in the SCC microenvironment.

Figure 2. SCC TAMs expressed pro-tumoral products in the tumor microenvironment.

Mean mRNA expression of (a) MMP9 and (b) MMP11 relative to HARP after adjustment for batch effect in normal skin (white bars), non-tumoral skin (NT, gray bars), and SCC (black bars) with standard error of the mean. *P <0.05, **P <0.01. CD163+ cells (green) demonstrated abundant co-localization with (c) MMP9 (red) and (d) MMP11 (red) in SCC compared to normal skin. Double positive cells appear yellow. Bar=100μm.

SCC TAMs expressed products of alternatively activated macrophages

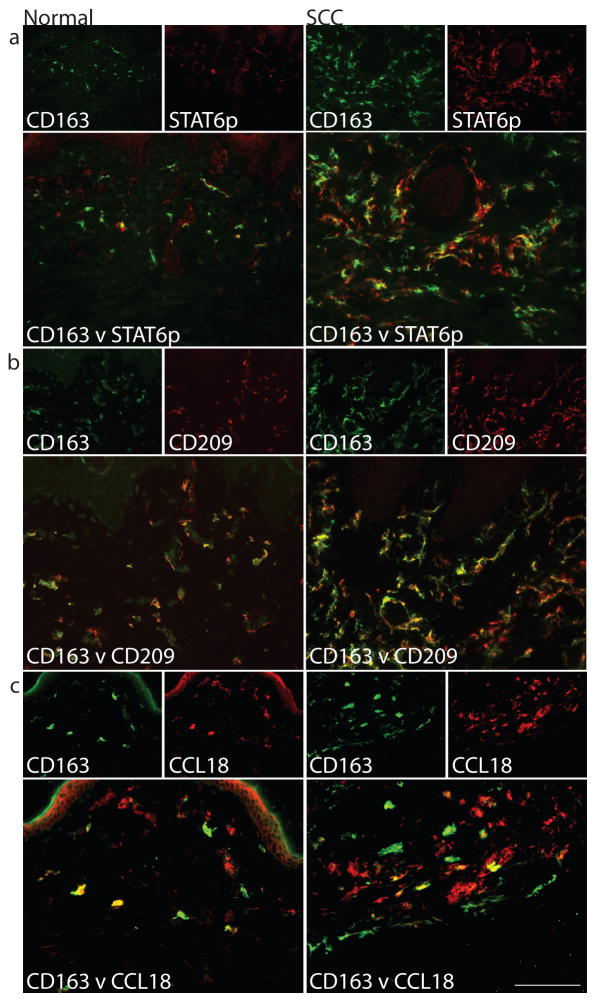

We evaluated expression of phosphorylated STAT6 (STAT6p) based on the association of Th2 cells and the tumor microenvironment (de Oliveira et al., 2009; Todaro et al., 2008). STAT6 plays an important role in signalling pathways that lead to the differentiation of Th2 cells, and STAT6p translocates to the nucleus in IL-4-activated cells (Forbes et al., 2010; Takeda et al., 1996). STAT6p co-localization with CD163 was abundant in the inflammatory infiltrate associated with SCC compared to normal skin (Figure 3a), suggesting the presence of IL-4 activation in TAMs.

Figure 3. SCC TAMs expressed products of alternatively activated macrophages.

Many CD163+ cells (green) co-expressed (a) phosphorylated STAT6 (STAT6p) (red), (b) CD209/DC-SIGN (red), and (c) CCL18 (red) compared to normal skin. Double positive cells appear yellow. Bar=100μm

To further evaluate the tumor microenvironment, we used M1 and M2 gene sets to correlate with the SCC genomic phenotype by using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Bluth et al., 2009; Lamb et al., 2006; Subramanian et al., 2005). We have used this approach previously (Bluth et al., 2009), and described it thoroughly in a prior publication (Suarez-Farinas et al., 2010). Fuentes-Duculan et al. recently published these sets of genes defining “M1” macrophages, induced with IFNγ, and “M2” macrophages, induced with IL-4, compared with control (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010). We hypothesized that there should be greater expression of M2 macrophage genes in the SCC genomic phenotype (Martinez et al., 2009; Siveen and Kuttan, 2009), defined by the SCC versus normal skin genes (Subramanian et al., 2007). However, the M2 gene set was not significantly enriched in SCC genomic phenotype, which may reflect that the M2 gene set is similarly expressed in both SCC and normal skin.

Despite the lack of enrichment of M2 genes in the SCC transcriptome, some published M2 genes (Martinez et al., 2006) were upregulated in our M2 gene set (Table 1), including CD209 (DC-SIGN) (Puig-Kroger et al., 2004; Soilleux et al., 2002), CCL17 (Bonecchi et al., 1998; Katakura et al., 2004) and CCL18 (Gustafsson et al., 2008; Kodelja et al., 1998; Kwan et al., 2008; Mantovani et al., 2004; Martinez et al., 2006). By double label immunofluorescence, CD163+ cells co-localized with CD209 and CCL18 in SCC and to a lesser extent in normal skin (Figure 3b–c). In the SCC microenvironment, we have thus shown that TAMs expressed some surface markers (CD209) and chemokines (CCL18) of M2-type macrophages. In addition and consistent with previous findings (Schutyser et al., 2005), we showed that in normal skin macrophages at steady state are in an alternatively activated state.

Table 1.

Representative upregulated genes in the M1 and M2 macrophage gene sets* and the SCC transcriptome**.

| Representative Genesa | M1 Gene Set | M2 Gene Set | SCC Transcriptomed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | STAT1 | 8.51 | c | 2.47 |

| Mx1 | 19.03 | c | 2.89 | |

| IL-23p19 | 3.10 | c | 2.34 | |

| IL-12/IL-23p40 | 3.36 | c | 1.11 | |

| CD127 | 4.44 | c | e | |

| M2 | CD209 | b | 9.25 | e |

| CCL18 | b | 3.43 | 3.55f | |

| CCL17 | b | 2.58 | 1.43 |

Genes representative of M1 and M2 macrophages were selected and their fold change in the M1 and M2 gene sets and the SCC transcriptome are listed.

Genes not differentially expressed in the M1 gene set compared to control.

Genes not differentially expressed in the M2 gene set compared to control.

SCC versus normal skin transcriptome, fold change and FDR <0.05.

HU95 chip did not include this probe.

FDR > 0.05

SCC TAMs expressed characteristics of classically activated macrophages in a microenvironment with Type-1 activation

While there was not any significant enrichment of M2 macrophage genes in the SCC genomic phenotype, the GSEA results did indicate that M1 macrophage gene sets were significantly enriched in the SCC genomic phenotype (Supplemental Table 1). Table 1 lists selected genes that were upregulated in both the M1 gene sets and the SCC versus normal skin transcriptome, indicating an M1-type macrophage activation pattern in the SCC microenvironment. It was perhaps surprising that there was such a marked M1 genomic signature in SCC. However, several recent studies have shown that IFNγ-producing T cells can be found in SCCs and other tumors (Huang et al., 2009; Koller et al.; Kryczek et al., 2009; Li-Weber and Krammer, 2003).

To confirm that macrophages in the SCC tumor microenvironment could be responsive to IFNγ, we performed double label immunofluorescence with CD163 and the two requisite chains of the IFNγ receptor. The IFNγ receptor 1 subunit (IFNγR1) that is internalized upon binding with IFNγ (Schroder et al., 2004) was present on the majority of macrophages in SCC compared to macrophages in normal skin, which did not express this receptor (Figure S1a). There is a second chain of IFNγ receptor (IFNγR2), which showed a similar pattern of co-localization with CD163+ cells in SCC compared to normal skin (Figure S1b). CD68+ macrophages in SCC also strongly expressed IFNγR1 and IFNγR2 compared to normal skin (Figure S1c–d). These data indicate that SCC TAMs are capable of responding to IFNγ. STAT1 and Mx-1, well-recognized IFNγ-induced genes (Landolfo et al., 1995; Saha et al.), were upregulated in the M1 gene set and SCC transcriptome (Table 1). Phosphorylated STAT1 (STAT1p), the form of STAT1 that translocates to the nucleus in IFNγ-activated cells, showed minimal expression in normal skin, but co-localized with CD163 in the juxtatumoral dermis of SCC (Figure 4a), indicating CD163+ macrophages in SCC were indeed responding to IFNγ.

Figure 4. SCC TAMs expressed characteristics of classically activated macrophages in a microenvironment with Type-1 activation.

Compared to normal skin, CD163+ cells co-expressed (a) phosphorylated STAT1 (STAT1p) (red), (b) CD127/IL7R (red), (c) IL-23p19 (red), and (d) IL-12/IL-23p40 (green). Double positive cells appear yellow. Bar=100μm

To further classify these SCC TAMs, the expression of markers and cytokines on TAMs considered to be representative of classical/M1 macrophage activation were evaluated (Table 1) (Martinez et al., 2006). There was increased gene expression of the marker CD127 (IL-7 receptor) and the cytokine subunits, IL-23p19 and IL-12/23p40 in the M1 macrophage gene set and increased gene expression of IL-23p19 in the SCC transcriptome (Table 1). The expression of CD127 has been shown to be strongly down regulated by IL-4 (Crawley et al.), which supports its role as an M1 marker. We confirmed these findings at the protein level by double label immunofluorescence. CD163+ TAMs abundantly co-expressed CD127 and produced IL-23p19 and IL-12/IL-23p40 compared to normal skin CD163+ macrophages (Figure 4b–d). Thus, in the SCC microenvironment, TAMs express surface markers (CD127) and cytokines (IL-23 subunits) of M1-type activated macrophages.

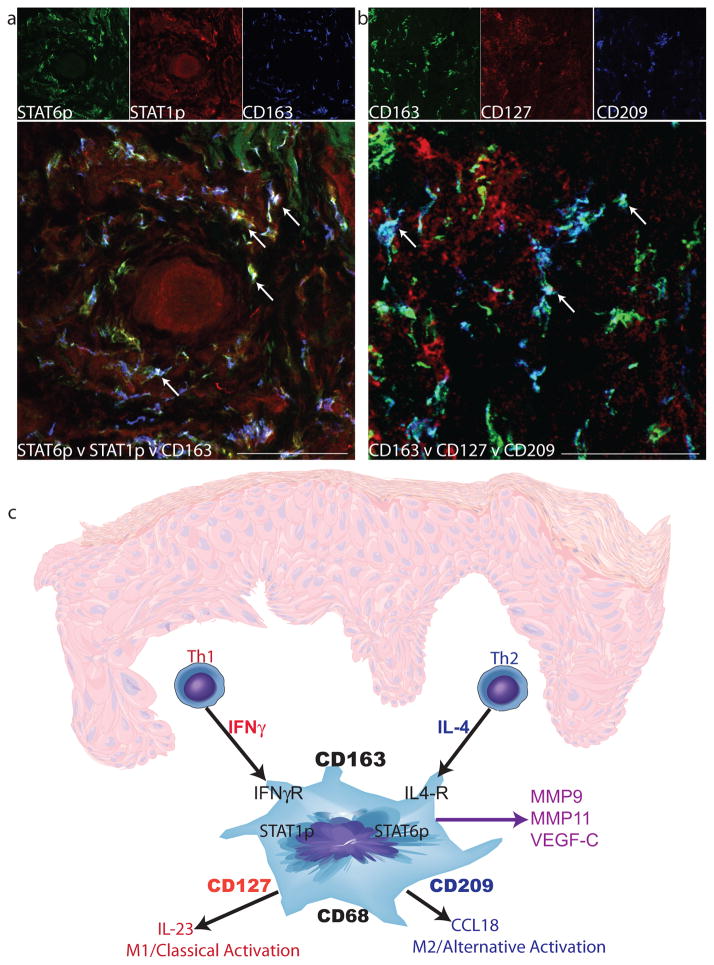

A subset of SCC TAMs simultaneously expressed markers of both classical and alternative activation

We have shown that TAMs in the SCC environment exhibit characteristics of both classical and alternative activation. However, it was not clear if there were two separate populations of macrophages driven by each cytokine, or if one subset of macrophages was responding to both cytokines simultaneously. Using triple label immunofluorescence and confocal imaging, some CD163+ cells were identified that co-localized with both STAT1p and STAT6p (shown by white arrows, Figure 5a), indicating that some SCC TAMs respond to both Th1 and Th2 signals and that there is a complex SCC tumor microenvironment of mixed Th1 and Th2 activation.

Figure 5. A subset of SCC TAMs simultaneously expressed characteristics of both classical and alternative activation.

Triple-labeled confocal immunofluorescence revealed the presence of (a) CD163+ cells (blue) that simultaneously co-expressed STAT6p (green) and STAT1p (red) and (b) CD163+ cells (green) that simultaneously co-expressed the markers CD127 (red) and CD209 (blue) in SCC. Triple-positive cells (white) are indicated by arrows. Bar=100μm. (c) The proposed model of SCC macrophage polarization. Th1 and Th2 cells produce cytokines, IFNγ and IL-4, respectively, and act on resident CD163+ macrophages to polarize these cells in several directions. IFNγ stimulates the M1 phenotype (CD127 and IL-23), and IL-4 stimulates towards the M2 phenotype (CD209 and CCL18). There is also production of mediators that are not driven by known polarizing cytokines, such as MMP9, MMP11, and VEGF-C. The overall outcome is a poly-activated TAM.

To further evaluate the TAM phenotype in this setting, we also identified a subpopulation of CD163+ macrophages that co-expressed both CD127 (upregulated in M1 macrophages) and CD209 (upregulated in M2 macrophages) (shown by white arrows, Figure 5b). There were also CD163+ cells that co-localized with CD127 only (yellow cells) and CD163+ cells that co-localized with CD209 (dark teal cells). This suggests that macrophage activation in SCC is heterogeneous, as we found several types of TAMs: M1 macrophages responding to Th1 signals, M2 macrophages responding to Th2 signals, and bi-activated macrophages responding to both Th1 and Th2 cytokines simultaneously.

DISCUSSION

Our studies suggest that CD163 should be considered the superior marker to identify TAMs in SCC. First, CD163+ TAMs were prominent and more abundant in the cutaneous SCC tumor microenvironment and significantly increased compared to macrophages in normal skin. Second, CD163 is the most sensitive marker for TAMs in SCC, as it identifies more dermal macrophages surrounding the tumor nodules than CD68. Third, CD163 is a more accurate marker of TAMs, because it did not co-localize with CD11c+ DCs in SCC, compared to CD68, which showed some overlap. This is similar in psoriasis, where CD163 had the least overlap with CD11c (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010). In addition, although CD163 was previously considered a macrophage marker solely for alternative activation, we have shown that CD163 not only identifies alternatively activated macrophages, but also classically and bi-activated macrophages in SCC. These findings suggest that future studies could benefit from using CD163 as a pan-macrophage marker in the skin.

To understand the cellular state of macrophage activation in the cutaneous SCC microenvironment, we must consider the setting in which these TAMs exist (Figure 5c). The tumor microenvironment is defined as a mixture of tumor and non-tumor cells at the dynamic interface of neoplasia (van Kempen et al., 2003). Prior studies have documented an influx of IFNγ-producing cells in the tumor microenvironment (Kryczek et al., 2009). We found a strong IFNγ genomic signature in the SCC tumor microenvironment coupled with evidence of upregulated IFNγ receptors and abundant IFNγ-activation of the infiltrating TAMs, indicating a Th1 type immune environment. However, the tumor microenvironment also has increased levels of Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) produced by both immune and tumor cells (Bluth et al., 2009; Lathers and Young, 2004; Pries and Wollenberg, 2006; Todaro et al., 2008). In our study, there was Th2 activation shown by phosphorylated STAT6 and CCL18 co-expression by CD163+ macrophages. Thus, these data suggest that TAMs in SCC respond to a dynamic mix of Th1 and Th2 signals.

These studies show that in normal skin at steady state, there is a predominant Th2/M2 environment. In contrast, SCC TAMs demonstrate features of both M1 and M2 activation. Conventionally, strong Th1/M1 responses should prevent tumor progression (Hung et al., 1998). Furthermore, in imiquimod treated SCC, increased levels of IFNγ in SCC induced anti-tumor effects and inhibited tonic anti-inflammatory signals of IL-10 (Huang et al., 2009). However, despite the presence of a strong M1 signal, the natural history of SCC is usually tumor progression, and hence this M1 signal is not able to eradicate the tumor. The mechanism for the ineffectiveness of Th1/M1 macrophages in eradicating the tumor is not clear, but may be due to the imbalance of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and their effects on TAMs.

Our study provides insight into the heterogeneous phenotypes and functions of TAMs. The effect of M1 and M2 TAMs may be to amplify immune responses to the tumor by inducing chemotaxis and activation of infiltrating T cells. The abundant influx of macrophages into the tumor microenvironment can also help promote tumor growth by stimulating angiogenesis and tissue remodelling. The pro-tumoral role of TAMs in SCC is supported by the production of pro-lymphangiogenic factors such as VEGF-C (Moussai et al., 2011). Our observation that TAMs produce MMP9 and MMP11 also supports their pro-tumoral role, as MMPs facilitate direct tumor spread and release of matrix-sequestered angiogenic factors that encourage tumor growth (Egeblad and Werb, 2002). Also, it is possible that tumors may produce factors that act on TAMs in a paracrine fashion (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001). A positive correlation between increased numbers of macrophages and poor prognosis in various human cancers has been demonstrated (Bingle et al., 2002; El-Rouby, 2010; Lin and Pollard, 2007; Nonomura et al., 2010; Shabo et al., 2008; Sica et al., 2006; Steidl et al., 2010). It is possible that the weaker classical activation state favors production of pro-carcinogenic growth factors by TAMs. Based on this, the potential to induce a more dominant M1 activation state in TAMs could be pursued as a promising target for therapeutic interventions.

There has been much debate over the phenotypic activation of TAMs as the physiology of macrophages has been shown to demonstrate remarkable plasticity (Mosser and Edwards, 2008; Siveen and Kuttan, 2009). Critics of the current linear model of macrophage polarization argue that the model does not allow for the plethora of possible macrophage activation states and capabilities. Our evidence suggests that the activation state of a macrophage cannot be pigeonholed into one category, and that the linear model of macrophage activation may not encompass all the potential roles of the macrophage. Therefore, we favor the dynamic color wheel model of macrophage activation proposed by Mosser and Edwards (Mosser and Edwards, 2008) as it accommodates the chameleon-like properties of this cell (Stout and Suttles, 2004).

MATERIALS and METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval (Weill Cornell Medical College) and informed consent was obtained before enrolling patients in this study, and the study adhered strictly to Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Samples used in study

For immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, cutaneous nodular Stage 1 SCC samples were obtained during Mohs micrographic surgery (n=3–18). Tumors were obtained from sun-exposed regions, namely head, neck and dorsal hands. All tumors were < 2 cm on examination and showed dermal invasion on light microscopy. Ten normal specimens were obtained via punch biopsies from non-sun exposed areas of patients without skin cancer and normal abdominoplasty tissue.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Standard procedures were used for immunohistochemistry as described (Bluth et al., 2009). Normal skin and SCC (n=8–18) were stained with macrophage markers CD163 and CD68 (antibodies in Supplemental Table 2) and a counterstain. Normal papillary dermis, designated as the tissue extending from the epidermal-dermal border to 100μm deep to the epidermis, and SCC “juxtatumoral dermis,” defined as the dermis 100μm circumferential to the tumor, were examined as previously described (Kaporis et al., 2007). Positive cells were counted using NIH IMAGE J software, and cell counts per unit area (μm2 × 100,000) were determined. Immunofluorescence stains were carried out in a standard manner (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010) (Supplemental Table 2). Images were acquired using either Zeiss Axioplan 2 widefield fluorescence microscope or upright confocal microscope. Dermal collagen fibers gave green autofluorescence, and antibodies conjugated with fluorochromes often gave background epidermal fluorescence. Single stain controls and isotype controls were performed for the confocal images (Figure S2).

Gene Array Analysis

SCC microarray data have been previously published (Haider et al., 2006). To estimate the fold-change of SCC versus normal skin, a moderated t-test available in limma package from R/Bioconductor was used, and genes were considered significant with a FCH>2 and FDR <0.05. GSEA was used to evaluate the enrichment of the macrophage transcriptomes in the SCC genomic phenotype (as defined by SCC vs Normal fold-change by microarray) as in a previous publication by our group (Suarez-Farinas et al., 2010) using GSEA desktop application (Lamb et al., 2006; Suarez-Farinas et al., 2010). The genomic transcriptomes of M1 and M2 macrophages derived from in vitro cytokine-stimulated macrophages have been published (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010). Macrophages were polarized by adding IFNγ, IL-4, TNF-α, LPS, and LPS plus IFNγ, and then compared to control macrophages. There were 585 upregulated and 334 downregulated probes in the M1 macrophages respectively, and 132 upregulated and 29 downregulated probes in the M2 macrophages respectively (Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010).

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was extracted from paired SCC and NT samples meeting the above inclusion criteria (n=15) and normal skin from healthy volunteers (n=10), using the RNeasy Mini KIT (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, U.S.A.). RT-PCR was performed as previously described (Chamian et al., 2005; Fuentes-Duculan et al., 2010). The PCR was performed in two batches. The first group was 10 paired SCC and NT, and 2 normals, and the second group was 5 paired SCC samples (described in Moussai et al., 2011) and 8 normal skin RNA. The primers for MMP9 and MMP11 were from Applied Biosystems (Hs00957562_m1 and Hs00171829_m1, respectively), normalized to HARP housekeeping gene. Since samples were obtained at two different time points, the log2 data was adjusted using a linear model to account for the batch effect.

Statistics

Cell counts were analyzed by Mann Whitney U test, and p-values reported. Logarithmic RT-PCR data was analyzed using paired t-test for SCC v NT and unpaired t-test to compare with normal skin control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by the Dana Foundation (Human Immunology Consortium Grant), which supports JSP, KCP, LF, AP-K, and JAC. MJB is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant T32-HL07423; MAL is supported by NIH grant 1 K23AR052404 and the Doris Duke Foundation, LJ-H is supported by the Doris Duke Foundation; MS-F is partially supported by NIH grant UL1 RR024143 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the Milstein Medical Research Program, CQFW is supported by the Milstein Medical Research Program. We thank plastic surgeon DM Senderoff for the generous donation of abdominoplasty surgical waste.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- TAMs

tumor-associated macrophages

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- FDR

false discovery rate

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have financial interests related to this work.

References

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254–65. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, Schioppa T, Saccani A, Sironi M, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-kappaB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation) Blood. 2006;107:2112–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluth MJ, Zaba LC, Moussai D, Suarez-Farinas M, Kaporis H, Fan L, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells from human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma are poor stimulators of T-cell proliferation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2451–62. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonecchi R, Sozzani S, Stine JT, Luini W, D’Amico G, Allavena P, et al. Divergent effects of interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma on macrophage-derived chemokine production: an amplification circuit of polarized T helper 2 responses. Blood. 1998;92:2668–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schonfisch B, Trilling B, Wehner-Caroli J, Rocken M, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buergy D, Weber T, Maurer GD, Mudduluru G, Medved F, Leupold JH, et al. Urokinase receptor, MMP-1 and MMP-9 are markers to differentiate prognosis, adenoma and carcinoma in thyroid malignancies. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:894–901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carucci JA. Cutaneous oncology in organ transplant recipients: meeting the challenge of squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:809–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2004.23440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamian F, Lowes MA, Lin SL, Lee E, Kikuchi T, Gilleaudeau P, et al. Alefacept reduces infiltrating T cells, activated dendritic cells, and inflammatory genes in psoriasis vulgaris. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409569102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley AM, Vranjkovic A, Young C, Angel JB. Interleukin-4 downregulates CD127 expression and activity on human thymocytes and mature CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1396–407. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira MV, Fraga CA, Gomez RS, Paula AM. Immunohistochemical expression of interleukin-4, -6, -8, and -12 in inflammatory cells in surrounding invasive front of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2009;31:1439–46. doi: 10.1002/hed.21121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rouby DH. Association of macrophages with angiogenesis in oral verrucous and squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:559–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E, van Panhuys N, Min B, Le Gros G. Differential requirements for IL-4/STAT6 signalling in CD4 T-cell fate determination and Th2-immune effector responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:240–3. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Duculan J, Suarez-Farinas M, Zaba LC, Nograles KE, Pierson KC, Mitsui H, et al. A subpopulation of CD163-positive macrophages is classically activated in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2412–22. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocheva V, Wang HW, Gadea BB, Shree T, Hunter KE, Garfall AL, et al. IL-4 induces cathepsin protease activity in tumor-associated macrophages to promote cancer growth and invasion. Genes Dev. 2010;24:241–55. doi: 10.1101/gad.1874010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C, Mjosberg J, Matussek A, Geffers R, Matthiesen L, Berg G, et al. Gene expression profiling of human decidual macrophages: evidence for immunosuppressive phenotype. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider AS, Peters SB, Kaporis H, Cardinale I, Fei J, Ott J, et al. Genomic analysis defines a cancer-specific gene expression signature for human squamous cell carcinoma and distinguishes malignant hyperproliferation from benign hyperplasia. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:869–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SJ, Hijnen D, Murphy GF, Kupper TS, Calarese AW, Mollet IG, et al. Imiquimod enhances IFN-gamma production and effector function of T cells infiltrating human squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2676–85. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaporis HG, Guttman-Yassky E, Lowes MA, Haider AS, Fuentes-Duculan J, Darabi K, et al. Human basal cell carcinoma is associated with Foxp3+ T cells in a Th2 dominant microenvironment. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2391–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakura T, Miyazaki M, Kobayashi M, Herndon DN, Suzuki F. CCL17 and IL-10 as effectors that enable alternatively activated macrophages to inhibit the generation of classically activated macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;172:1407–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodelja V, Muller C, Politz O, Hakij N, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S. Alternative macrophage activation-associated CC-chemokine-1, a novel structural homologue of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha with a Th2-associated expression pattern. J Immunol. 1998;160:1411–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller FL, Hwang DG, Dozier EA, Fingleton B. Epithelial interleukin-4 receptor expression promotes colon tumor growth. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1010–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryczek I, Banerjee M, Cheng P, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, et al. Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood. 2009;114:1141–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan WH, Navarro-Sanchez E, Dumortier H, Decossas M, Vachon H, dos Santos FB, et al. Dermal-type macrophages expressing CD209/DC-SIGN show inherent resistance to dengue virus growth. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006;313:1929–35. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolfo S, Gribaudo G, Angeretti A, Gariglio M. Mechanisms of viral inhibition by interferons. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;65:415–42. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)98599-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathers DM, Young MR. Increased aberrance of cytokine expression in plasma of patients with more advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cytokine. 2004;25:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4625–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Weber M, Krammer PH. Regulation of IL4 gene expression by T cells and therapeutic perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:534–43. doi: 10.1038/nri1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Li JF, Gnatovskiy L, Deng Y, Zhu L, Grzesik DA, et al. Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11238–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages press the angiogenic switch in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5064–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–86. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussai D, Mitsui H, Pettersen JS, Pierson KC, Shah KR, Suarez-Farinas M, et al. The Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Microenvironment Is Characterized by Increased Lymphatic Density and Enhanced Expression of Macrophage-Derived VEGF-C. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:229–36. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura N, Takayama H, Kawashima A, Mukai M, Nagahara A, Nakai Y, et al. Decreased infiltration of macrophage scavenger receptor-positive cells in initial negative biopsy specimens is correlated with positive repeat biopsies of the prostate. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1570–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto CA, Carvalho PE, Antonangelo L, Garippo A, Da Silva AG, Soares F, et al. Morphometric evaluation of tumor matrix metalloproteinase 9 predicts survival after surgical resection of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3098–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries R, Wollenberg B. Cytokines in head and neck cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:141–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Kroger A, Serrano-Gomez D, Caparros E, Dominguez-Soto A, Relloso M, Colmenares M, et al. Regulated expression of the pathogen receptor dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM-3)-grabbing nonintegrin in THP-1 human leukemic cells, monocytes, and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25680–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu-Mourez R, Solis M, Nardin A, Goubau D, Baron-Bodo V, Lin R, et al. Distinct roles for IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and IRF-7 in the activation of antitumor properties of human macrophages. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10576–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha B, Jyothi Prasanna S, Chandrasekar B, Nandi D. Gene modulation and immunoregulatory roles of interferon gamma. Cytokine. 2010;50:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:163–89. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutyser E, Richmond A, Van Damme J. Involvement of CC chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18) in normal and pathological processes. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:14–26. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabo I, Stal O, Olsson H, Dore S, Svanvik J. Breast cancer expression of CD163, a macrophage scavenger receptor, is related to early distant recurrence and reduced patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:780–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SA, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS, Stroud RE, Chang EI, Reed CE. Differential matrix metalloproteinase levels in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.12.016. discussion 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siveen KS, Kuttan G. Role of macrophages in tumour progression. Immunol Lett. 2009;123:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soilleux EJ, Morris LS, Leslie G, Chehimi J, Luo Q, Levroney E, et al. Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulations in situ and in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:445–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, Farinha P, Han G, Nayar T, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RD, Suttles J. Functional plasticity of macrophages: reversible adaptation to changing microenvironments. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:509–13. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Farinas M, Lowes MA, Zaba LC, Krueger JG. Evaluation of the psoriasis transcriptome across different studies by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) PLoS One. 2010;5:e10247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3251–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Tanaka T, Shi W, Matsumoto M, Minami M, Kashiwamura S, et al. Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signalling. Nature. 1996;380:627–30. doi: 10.1038/380627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro M, Lombardo Y, Francipane MG, Alea MP, Cammareri P, Iovino F, et al. Apoptosis resistance in epithelial tumors is mediated by tumor-cell-derived interleukin-4. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:762–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen LC, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GN, Coussens LM. The tumor microenvironment: a critical determinant of neoplastic evolution. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82:539–48. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, He F, Feng F, Liu XW, Dong GY, Qin HY, et al. Notch signaling determines the M1 versus M2 polarization of macrophages in antitumor immune responses. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4840–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg AS, Ogle CA, Shim EK. Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:885–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaba LC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Steinman RM, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. Normal human dermis contains distinct populations of CD11c+BDCA-1+ dendritic cells and CD163+FXIIIA+ macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2517–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI32282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZS, Chu YQ, Ye ZY, Wang YY, Tao HQ. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase 11 in human gastric carcinoma and its clinicopathologic significance. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:686–96. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.