Abstract

Many neurological disorders are caused by perturbations during brain development, but these perturbations cannot be readily identified until there is comprehensive description of the development process. In this study, we performed mass spectrometry analysis of the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions from three rat brain regions at four postnatal time points. To quantitate our analysis, we employed 15N labeled rat brains using a technique called SILAM (Stable Isotope Labeling in Mammals). We quantified 167,429 peptides and identified over 5000 statistically significant changes during development including known disease associated proteins. Global analysis revealed distinct trends between the synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondrial proteomes and common protein networks between regions each consisting of a unique array of expression patterns. Finally, we identified novel regulators of neurodevelopment that possess the identical temporal pattern of known regulators of neurodevelopment. Overall, this study is the most comprehensive quantitative analysis of the developing brain proteome to date providing an important resource for neurobiologists.

Keywords: brain development, quantitation, metabolic labeling, SILAM, MudPIT

Introduction

Genetic1–3 and environmental 4–6 perturbations during brain development have been reported to be responsible for devastating neurological disorders. For example, schizophrenia is a complex disease affecting about 1% of the U.S. population. Manifesting in late adolescence or young adulthood, symptoms include hallucinations, paranoid delusions, disorganized cognition and social withdrawal. Although it has been estimated that 80% of the disease is heritable, the identification of definitive genetic factors has eluded the scientific community 7. Extensive genetic research nevertheless has amassed susceptibility genes, copy number variations, de novo mutations, and chromosomal “hotspots” associated with different populations of patients 8. A prevalent theory of schizophrenia posits that the disease results from aberrations during brain development long before the development of clinical symptoms 9. Although there is a great degree of discordance between individual genes associated with schizophrenia in existing studies, many reports have suggested an overrepresentation of genes involved in neurodevelopment10–13. One caveat is that many of the susceptibility genes identified have no known function in the brain, and this problem is compounded by the inherent complexity of normal brain development. Although individual proteins and circuits have been elegantly studied, a systematic understanding of molecular events during brain development is still lacking, and this information has been proposed as a prerequisite to identify perturbations in schizophrenia and other neurodevelopmental disorders14, 15. Large scale gene expression analyses have quantified thousands of changes in gene expression during brain development in multiple brain regions16–18. Spatial complexity, however, goes beyond discrete brain regions for the neuron itself possesses spatially distinct compartments and global subcellular analysis can only be studied by proteomics.

The goal of this study is to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of the brain proteome by quantifying developmental proteomic trends in subcellular neuronal compartments. SILAM (Stable Isotope Labeling in Mammals) analysis19,20 is performed on two neuronal subcellular structures: synapses and mitochondria. Dysfunction in both compartments has been implicated in neurodevelopmental diseases21–25, but how these proteomes change during development has not been studied. In humans, brain development occurs from gestation through adolescence, while in Rattus norvegicus, many of these events, including neuronal migration, synaptogenesis, glial proliferation, axonal proliferation, dendritic proliferation, and myelination, occur in the first fifty postnatal days providing a convenient model of development26. Specifically, two time points are analyzed before and after a major burst in synaptogenesis. We chose to analyze three well-studied brain regions (cerebellum, cortex, and hippocampus) that underlie three different functions (motor coordination, cognition, and memory). In total, 167, 429 peptides are quantified and 3081 statistically significant changes are found during development and 1896 statistically significant changes between brain regions. Distinct global trends were observed between the subcellular proteomes. We mined the dataset for potential novel regulators of neurodevelopment that share an identical temporal pattern as known regulators of neurodevelopment. This is the first time many of these proteins have been described in brain tissue and the temporal pattern for a subset of these proteins is verified. We provide all our quantitative data and raw MS data in an online searchable database (braindevelopment.scripps.edu). Overall, this study represents the first quantitative proteomic study dissecting the temporal dynamics of brain development at two spatial levels: brain regions and subcellular compartments.

Results

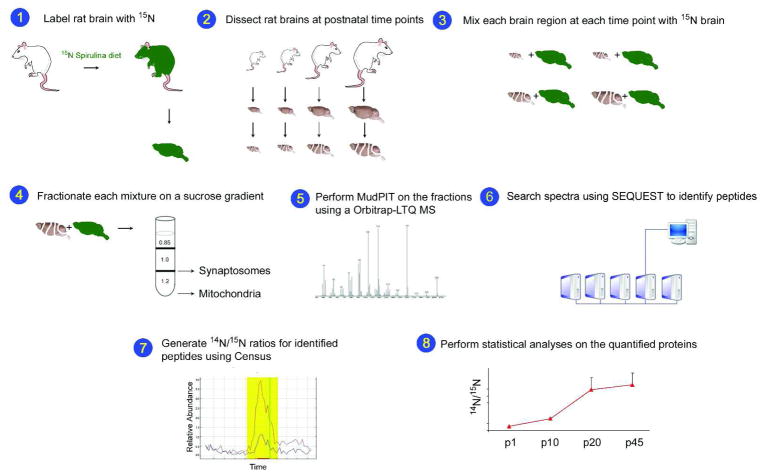

The workflow used in this study is outlined in Figure 1. To quantify the brain proteome during postnatal development, rat brains were 95% enriched with 15N by feeding animals a protein-free rat chow diet supplemented with 15N labeled proteins from Arthrospira platensis20. A 1:1(wt/wt) 15N labeled total brain homogenate from postnatal day 45 (p45) rats was mixed with cerebellar, cortical or hippocampal homogenate from unlabeled (14N) rats at p1, p10, p20, and p45. The 15N labeled brains were not dissected, so all the analyses would contain the same internal standard (i.e. p45 15N total brain homogenate) allowing the quantification between the brain regions and developmental time points using a “ratio of ratios” strategy19. For example, 14N hippocampus/15N hippocampus could not be compared directly to 14N cerebellum/15N cerebellum, but 14N hippocampus/15N whole brain can be compared to 14N cerebellum/15N whole brain. This resulted in twelve 14N/15N homogenate mixtures, and each mixture was fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient to isolate the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions. The samples were then analyzed by MudPIT (Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology) in duplicate 27, 28. A total of 2590 and 2857 non-redundant proteins were identified with at least two peptides from the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions, respectively, at a protein false discovery rate of < 1% (Tables S1 and S2). We quantified (i.e. generated confident 14N/15N ratios) 87% and 96% of the identified proteins in the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions, respectively. Over 80% of the proteins were quantified with more than two peptides resulting in greater statistical precision in the measurements (Figure 2A). The synapse is an “open organelle” with proteins trafficking in and out, its own translational machinery, and mitochondria. Thus, many proteins found in the synapse are also localized to other cellular compartments making the annotation of this dynamic compartment challenging compared to membrane bound organelles, such as mitochondria. Throughout the remainder of this paper, the “mitochondrial fraction” will refer only to the Gene Ontology (GO) annotated mitochondrial proteins.

Figure 1. Schematic of the study.

Rats were labeled with 15N and the 15N labeled p45 brains (green) were removed and homogenized (1). The hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum were dissected from unlabeled (14N) rats at p1, p10, p20, and p45 (2). The 15N total brain homogenate was mixed 1:1(wt/wt) with each of the14N brain regions (3). The synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions were isolated from each mixture using a discontinuous sucrose gradient (4). Each fraction was analyzed by MudPIT on an LTQ-Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (MS) (5). The MS data was searched with SEQUEST to identify the peptides and subsequent proteins in each fraction (6). Census calculated the 14N/15N ratios for the identified peptides. An example of the Census output with the 14N (red line) and the corresponding 15N (blue line) peptide abundances is shown. The y-axis is relative abundance and the x-axis is time. (7). Statistical analyses were performed on the average 14N/15N protein ratios. The 14N/15N ratios for the protein synaptophysin from the synaptosomal fraction in the cortex are shown (8).

Figure 2. Quantitative differences during development within a brain region.

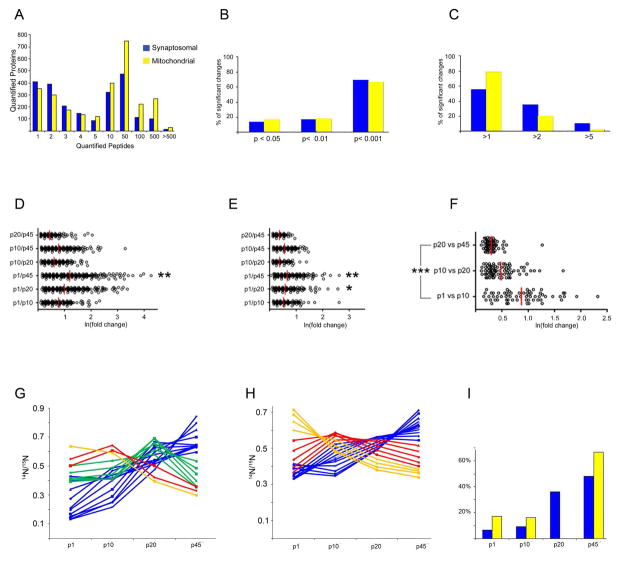

A, Eighty-two percent and 87% of the proteins quantitated from the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions were quantitated by at least two peptides. B, In the synaptosomal fraction, 69 % (1216) of the significant changes were highly significant (p < 0.001, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons), while in the mitochondrial fraction, 66 % (876) of these significant changes were highly significant. C, In the synaptosomal fraction, 45 % (795) of these significant changes represented a greater than two-fold change in protein expression, while in the mitochondrial fraction, 22 % (281) of these significant changes represented a greater than two fold change in protein expression. D., All the significant changes from all brain regions were plotted based on the natural log (ln) of their magnitude of change on the x-axis. In the synaptosomal fraction, the magnitude of the changes between the p1 and p45 samples was significantly (*p < 0.001) greater than all other comparisons. The red bar represents the median. E., In the mitochondrial fraction, the same pattern was observed, except the significance of the difference between p1 vs. p45 and p1 vs. p20 was **p < 0.05. F., Within each fraction, the magnitude of the changes observed in the p1 vs. p10 comparison was significantly (***p < 0.001) greater than the p20 vs. p45 comparison. The hippocampus from the synaptosomal fraction is shown and the other regions are in Figure S1. The significant changes were analyzed by SOM analysis, which generated 20 temporal clusters for the synaptosomal (G) and mitochondrial (H) fractions. The genes which compromise each cluster can found in Table S19 and S20. The y-axis represents the average 14N/15N ratio and each line represents a group of proteins with an identical developmental temporal trends. These protein clusters could be categorized into four general developmental expression patterns: a decrease with age (yellow), a peak of expression at p10 (red), a peak of expression at p20 (green), and an increase with age (blue). I., The data from the SOM analysis is plotted by the percentage of protein in the analysis (y-axis) that was observed in each temporal trend.

The brain proteome is most dynamic in the neonate

First, we analyzed differences between time points with a brain region. In total 1753 and 1328 significant changes were identified in the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions, respectively (Tables S3–8). When the changes were pooled from all the brain regions, over 65% of these changes in both fractions were highly significant (p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). Forty-five percent of changes in the synaptosomal fraction were greater than two-fold, while only 22% of changes in the mitochondrial fraction were greater than two-fold (Figure 2C). The differences between the p1 and p45 samples were significantly greater than all other comparisons (Figure 2D and E). The magnitude of the change, however, was not proportional to the number of days between the time points. For example, we observed the changes between p20 and p45 samples were less than other comparisons. When we examined how protein expression changed with age, the p1/p10 comparisons had significantly greater change in protein expression than the p20/p45 comparisons in all brain regions and fractions (Figure 2F and S1). Overall, this analysis reveals that the synaptosomal and mitochondrial proteomes are most dynamic early in postnatal life, and the synaptosomal proteome is more dynamic than the mitochondrial proteome.

Differential regulation of protein functional groups during brain development

To identify the temporal protein expression patterns in the dataset, clustering analysis was performed. For this analysis, the input was only proteins that exhibited a significant difference during development. Twenty clusters of proteins were observed, which could be grouped into four temporal trends: 1) expression decreasing with age, 2) expression increasing with age, 3) expression the highest at p10, and 4) expression the highest at p20 (Figure 2G and H, Table S9 and S10). The majority of the proteins in this analysis were observed to increase with age (Figure 2I), which corresponds to an increase in mass and protein content during development. Importantly, employing the p45 labeled brain as an internal standard allowed for the normalization of the total protein content to reveal these temporal patterns. One difference between the fractions was that there were no clusters that peaked at p20 in the mitochondrial fraction. Next, we sought to determine if the proteins involved in a particular function were significantly represented within a temporal pattern (Figure S2). In the mitochondrial fraction, proteins whose expression peaked at p1 and p10 were involved in metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids. In the synaptosomal fraction, there were no significant enrichment of functional groups amongst proteins whose expression peaked at p1, but the p10 pattern was enriched in proteins involved in neurite outgrowth. This included Rac1, which plays a central role in regulating the actin cytoskeleton during axon guidance 29. Proteins that peaked at p20 in the synaptosomal fraction and at p45 in the mitochondria fraction were associated with the metabolism of ATP. The clusters that increased with age in the synaptosomal fraction were associated with synaptic transmission. In addition, many of these proteins in this analysis have been reported to be involved in neurological disorders (Figure S3 and Table S11). Overall, this data analysis demonstrates differential regulation of protein functional groups between subcellular compartments during brain development.

Comparison of proteomes between brain regions

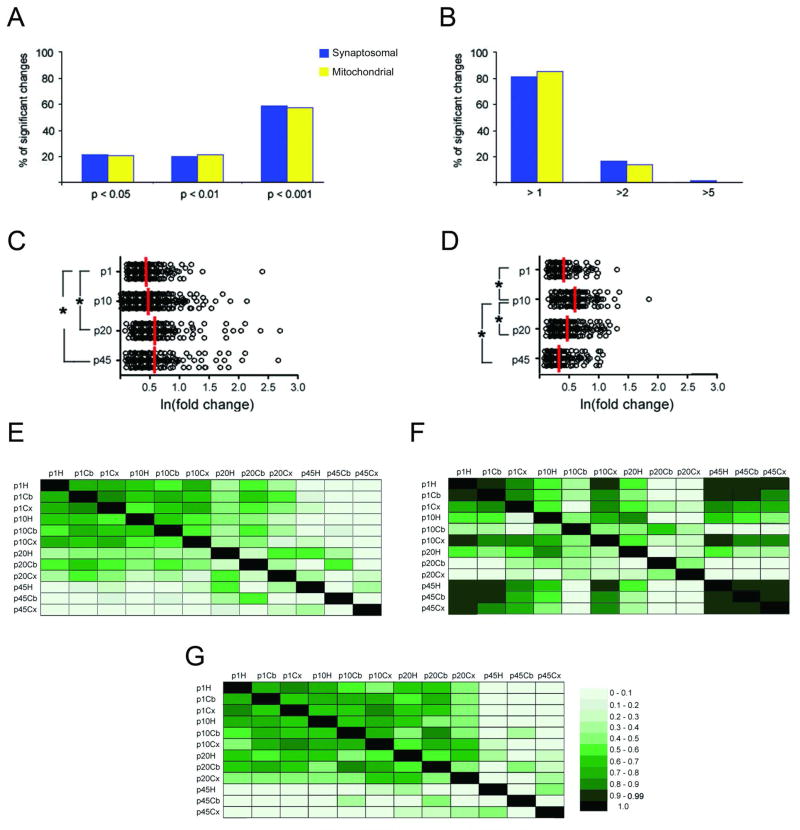

Different brain regions have specialized functions and thus how protein expression differs in these brain regions during development was determined. A total of 1050 and 846 significant changes between the brain regions at a measured time point were identified in the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions, respectively (Tables S12–19). In contrast to the previous analysis, less than 19% of the changes were greater than two-fold in both fractions, but similar to the previous analysis, the majority of these changes were highly significant (Figure 3A and B). In the synaptosomal fraction, the magnitude of these differences increased with age, while the largest changes between brain regions in the mitochondrial fraction were observed at p10 (Figure 3C and D). Correlation analysis was performed to determine the similarity of regional specific proteomes during development. For the synaptosomal fraction, the brain regions were highly correlated with one another at p1 and p10 (Figure 3E). In contrast, the p45 and p20 synaptosomal regional proteomes correlated the best with themselves. For example, the p45 hippocampal proteome was the most similar to the p20 hippocampal proteome, which parallels the development of hippocampal dependent behaviors 30. In the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 3F), the brain regions were highly correlated at p1 and p45, and the least correlation between the brain regions was at p10 and p20. To determine if this distinct pattern was inherent to all mitochondrial proteins, we performed correlation analysis only on the GO annotated mitochondrial proteins that were quantitated in the synaptosomal fraction (Figure 3G). The synaptosomal mitochondrial proteome followed a pattern similar to the entire synaptosomal proteome. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the synaptosomal proteomic differences between brain regions are the greatest in the adult, but the mitochondrial proteomic analysis suggests there are differences during development that also defines these functionally distinct brain regions.

Figure 3. Differential protein expression between brain regions during development.

A., In the synaptosomal fraction, 59%(620) of these significant changes were highly significant(p < 0.001, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons), while in the mitochondrial fraction, 58%(490) of these significant changes were highly significant. B, Eighteen percent (199) of these significant changes represented a greater than two fold change in protein expression, while in the mitochondrial fraction, 14%(119) of these significant changes represented a greater than two fold change in protein expression. C., In the synaptosomal fraction, the magnitude of the changes between the brain regions at p45 and p20 was significantly greater than the brain regions at p1. D., In the mitochondrial fraction, magnitude of the changes between the brain regions at p10 was significantly greater than the brain regions at all other time points. * p < 0.001. All the significant changes were plotted based on the natural log (ln) of their magnitude of change on the x-axis. The red bar represents the median. The quantitated proteins were analyzed with Pearson’s correlation test from synaptosomal fraction (E), mitochondrial fraction (F), and the GO annotated mitochondrial proteins from the synaptosomal fraction (G). The darker the green color represents a high correlation coefficient (r2). All the correlations were significant ( p < 0.0001). H = hippocampus, Cb = Cerebellum, Cx = Cortex.

Protein functional groups are differentially regulated between brain regions

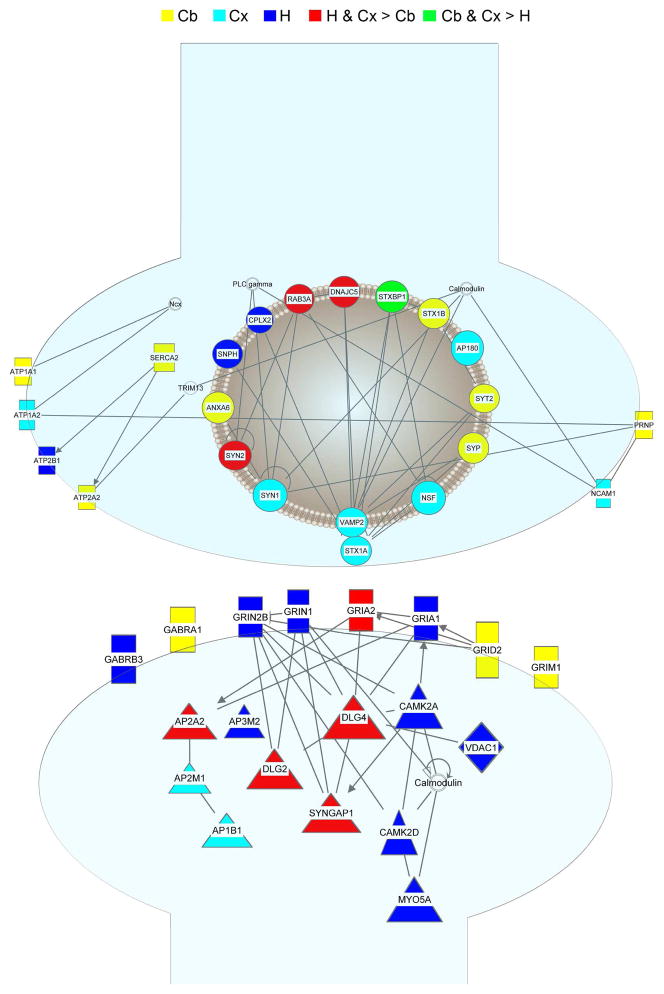

Functional differences between the brain regions during development were determined using network analysis. The three most frequent protein functional groups represented by the differences between the brain regions in the synaptosomal fraction were synaptic transmission, ion transport, and neurite growth (Figure S4A–C). The differences in neurite outgrowth proteins were restricted to the earlier time points consistent with our clustering analysis. Network analysis was performed on the proteins annotated to synaptic transmission and ion transport function (Figure 4). The p45 time point was chosen because differences in expression at this time point were the largest, and it was observed that many of the differentially regulated proteins were interconnected (Table S20). For the mitochondria fraction, proteins involved in the metabolism of ATP were the most frequent functional category observed to be differentially regulated between brain regions (Figure S4D). All of these proteins were components of the well-annotated electron transport chain (ETC). The ETC network was constructed using the differentially regulated proteins at p10 where the largest differences were observed (Figure 5D and E). In the mitochondrial fraction, many of the proteins were highly expressed in the cerebellum, but in the synaptosomal fraction, the highest expression levels shifted from the cerebellum to the cortex. This shift was most evident in complex III. Thus, this analysis demonstrates common subcellular networks are differentiated between regions by a unique combination of protein expression levels.

Figure 4.

Synaptic Network. The lines in the synaptic network represent direct interactions. Circles represent proteins affiliated with synaptic vesicles. Rectangles represent transmembrane proteins, and cytoplasmic proteins are represented by triangles. Yellow represents up-regulated in the cerebellum, light blue represents up-regulated in the cortex, dark blue represents up-regulated in the hippocampus, red represents up-regulated in the hippocampus and cortex compared to the cerebellum, and green represents up-regulated in the cerebellum and cortex compared to the hippocampus. Shapes without color are proteins not in our dataset.

Figure 5. Functional differences in the mitochondrial fraction between brain regions.

The median 14N/15N ratio for GO annotated mitochondrial proteins from the mitochondrial (A) and synaptosomal (B) fractions is significantly less than in the cortex (green) and the cerebellum (blue) compared to the hippocampus (red). In A, hippocampus vs. cortex (p < 0.001); hippocampus vs. cerebellum (p < 0.001), cerebellum vs. cortex (p > 0.05). In B, hippocampus vs. cortex (p < 0.001); hippocampus vs. cerebellum (p < 0.01), cerebellum vs. cortex (p > 0.05). The lines in the mitochondria network represent direct interactions and the Roman numerals represent the complex number of the ETC. Tan color represents the protein is the greatest in the cerebellum, then the cortex, then the hippocampus. Dark green represents the protein is up-regulated in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus and the cortex. Dark blue represents the protein is greater in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus. Red represents the protein is up-regulated in the cerebellum and cortex compared to the hippocampus. Yellow represents the protein is the greatest in the cortex, then cerebellum, and the least in the hippocampus. Light green represents the protein is the greatest in the cortex compared to the hippocampus and cerebellum. Light blue represents the protein is up-regulated in the cortex compared to the hippocampus.

Novel regulators of neuronal development

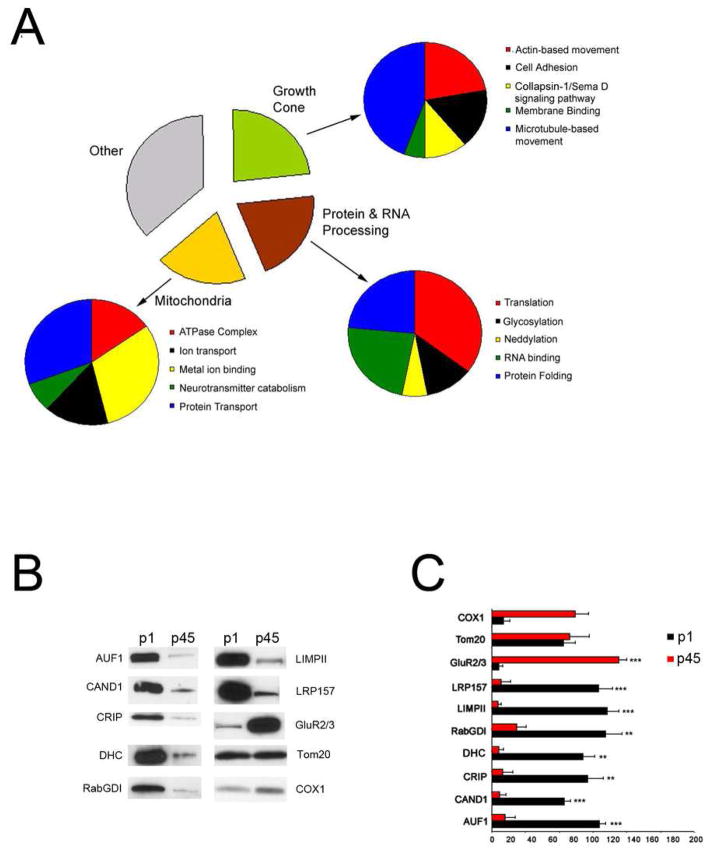

As deficits in synaptic development are thought to be a basis for many diseases, the data was mined to identify novel regulators of brain development in the synaptosomal fraction. Proteins whose expression was up-regulated in p1 brains compared to other time points in the synaptosomal fraction were identified, because this temporal pattern is exhibited by known regulators of neuronal development. In total, seventy-one annotated proteins were observed to be up-regulated at p1 (Table S21–2). Twenty-two of these proteins have been reported to be up-regulated early in postnatal development by other protein quantitation methods, and five additional proteins corresponded to reports quantitating mRNA or protein activity. Consistent with our observations, some of these proteins are known regulators of neurodevelopment, including neural cell adhesion molecule31, Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha(RabGDIα)32, collapsin response mediator protein-233, 34, and myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate35. In addition, ~25% of these proteins have been reported as integral to the growth cone, which is an actin enriched extension at the tip of nascent axons seeking synaptic targets (Figure 6A). This provides confidence that the other novel neuronal proteins regulate synaptic development based on “guilt by association”. Quantitative western blot analysis was performed on the synaptosomal fraction probing for nine proteins whose temporal protein expression pattern during brain development has not been reported. Seven proteins had a significant increase of expression in p1 samples compared to the p45 samples (Figure 6B and C). During the preparation of this manuscript, another novel protein in this dataset was reported to be crucial for neurodevelopment. The phosphorylation of stathmin-2 was reported to be necessary for neuronal migration36. Westerlund et al. proposed that the regulation of microtubules by stathmin-2 at the growth cone drove the protrusive force required for neurite extension and subsequent neuronal migration.

Figure 6. Regulators of Neuronal Development.

A, The proteins whose expression peaked at p1 in the synaptosomal fraction are organized by their biological function using GO. B, Three synaptosomal fractions from p1and p45 were analyzed by western blot analysis with antibodies for a subset of proteins in A. As a positive control, the synaptosomal fractions were probed with an antibody for the glutamate receptor subunit 2/3(GluR2/3), whose expression has been previously reported to increase during brain development. A representative blot is shown. C, Graphical representation of the analysis of the pixel intensity of each blot. The x-axis is the pixel intensity, black represents p1, and red represents p45. Protein abbreviations:CAND1 (cullin associated and neddylated dissociated protein), LIMPII (Lysosome membrane protein 2), CRIP (Cysteine rich protein 2), Tom20 (Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM20), COX1(Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1), RabGDI(Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha), DHC (dynein heavy chain), LRP157(Leucine rich protein 157), and AUF1(AU-rich element RNA-binding protein 1). *** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.001,* p < 0.01 indicates results of t-tests between the p1 and p45 samples of an individual protein.

Discussion

Developing postnatal brain proteomes

Since we quantified subcellular proteomes during development, it is difficult to perform a gene to gene comparison with published microarray studies, where subcellular localization is disregarded. Nevertheless, many of the global trends we observed in our study correspond to a previous report examining the global gene expression of the hypothalamus, cortex, and hippocampus during brain development17. Both studies observed the largest changes within a brain region at the earliest developmental time points examined suggesting that the later postnatal changes represent “fine tuning” of individual brain regions. Both studies also observed that changes during development within a brain region were larger compared to the changes observed between the brain regions at a given time point. We observed these trends in both fractions examined, but the synaptosomal fraction was more dynamic than the mitochondrial fraction, which likely reflects the large burst in synaptogenesis during the time course 37. Similar to gene expression analysis, we observed that proteins which share function also share expression patterns during development; however, our proteomic analysis further revealed the functional groups displayed different patterns based on the fraction examined. Consistent with the neonate’s diet of mother’s milk resulting in an increase of fatty acids in the body before glucose becomes the main metabolic fuel after weaning26, proteins whose expression peaked at p1 and p10 were involved in metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids in the mitochondrial fraction. In contrast, proteins that peaked at p10 in the synaptosomal fraction were associated with the extension of neuronal processes. The proteins whose expressed increase linearly with age were annotated as supporting synaptic transmission and metabolism of ATP for the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fraction, respectively. This is consistent with the general idea that neuronal function and energy utilization are tightly coupled. This is best exemplified by the fact that it has been estimated that 40–60% of the entire ATP pool in the adult brain is expended on ion gradients, which are compulsory for neuronal function38. Overall, genomic and proteomic data generated similar global developmental trends, but proteomic analysis allowed the localization of protein functional groups.

Differential trends between synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions

Proteomic analysis between brain regions showed the synaptosomal fraction to be the most distinct at p45, while the mitochondrial fraction was most distinct at p10 and p20. Furthermore, the synaptosomal mitochondria did not follow the trend of the mitochondrial fraction. This synaptic pattern suggests that during development the regional synaptic proteomes become distinct to support specific functions (i.e. memory and motor coordination) as previously proposed by gene expression analysis 17. The observed patterns with the mitochondria fraction have not been reported since there is the first quantitative proteomic analysis of the fraction in the developing brain. It suggests that there is a divergence in the energy demands of the developing regions during this critical period, which is a dynamic time with bursts in synaptogenesis, axonal and dendritic proliferation, mitochondrial number, and mitochondrial volume. While the exact biological significance is unclear, many studies have also observed differences between synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria39, 40, 41, 42, 43–48. The precise function of mitochondria localized at the synapse remains elusive, but it has been demonstrated to be critical for normal brain function49, 50,51–53. Thus, our proteomic analysis supports previous reports that there are biochemical differences between synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria, which may underlie discrete functions in the developing brain.

Synaptic Network

Synapses can be categorized based on their structure, functional characteristics, and molecular composition proposing a diversity that is currently unfathomable. Regarding molecular composition, synapses are historically defined by the type of neurotransmitter released from the presynapse and the receptors on the adjoining postsynapse. Extensive proteomic analysis has been performed on the PSD of glutamatergic synapses54–57. Our quantitative synaptic network is smaller than these qualitative dataset for two main reasons. First, not all proteins that are identified can be quantified (limit of quantitation (LOQ) is higher than limit of detection (LOD)). Second, many proteins did not pass our strict filtering and statistical analysis. Nevertheless, our study did indeed observe distinct regional expression patterns of neurotransmitter receptors, which correlated with the literature. In addition, we observed differential expression patterns of proteins crucial to synaptic vesicle release. The SNARE (soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complex consisting of VAMP2, syntaxin, SNAP-25, and NSF, exocytoses synaptic vesicles at the presynaptic plasma membrane58, 59. We observed three of the core components differentially expressed in the brain. Although the molecular composition of the SNARE complex has been solved, the exact molecular details and sequence of events of synaptic vesicle release is still controversial. However, it is known that there are many auxiliary proteins that are crucial to the regulation of this process and our dataset suggests these proteins also possess region specific expression patterns. Furthermore, altered expression of other synaptic vesicle proteins have been implicated in neurological disorders60–67. For example, altered expression of SNAP-25 has been observed in specific brain regions in postmortem brains of people diagnosed with bipolar disorder68, and synaptotagmin expression declines early in Alzheimer’s disease before the loss of synapses65. Although these proteins support the same basic synaptic function, their varied expression among the brain regions suggests they have a modulatory effect instead of (or in addition to) their elementary role in neurotransmission. Similarly, imaging studies in the intact brain have observed heterogeneity in the synaptic vesicle machinery between inhibitory and excitatory synapses69. Overall, this data suggests a uniform synaptic network is shared between brain regions, but a combinatorial expression pattern distinguishes each brain region possibly to support discrete functions.

Conclusion

The brain regions examined in this study are each composed of multiple neuronal cell types each of which can form a variety of synapses. The isolation of molecularly distinct neuronal type or synapse from brain tissue is currently an obstacle for any biochemical analysis. Nevertheless, our proteomic snapshot of these individual brain regions demonstrates that synapses and mitochondria possess a protein network common between brain regions, but each region consists of a signature array of protein expression levels. Many studies have manipulated the genes described in our dataset to infer function based on the resulting behavioral or biochemical phenotype. However, the functional differences between protein networks possessing distinct expression patterns as described here has not yet been explored. Our study provides a useful catalog of thousands of protein expression changes for the neuroscience community and a greater understanding of how discrete proteomes are altered during development. Finally, with differential temporal patterns identified between these regions and subcellular compartments, we conclude quantitative spatiotemporal proteomic analysis is necessary for complete understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying animal models of neurological disease.

Experimental Procedures

Metabolic 15N Labeling of Rat brains

Sprague-Dawley rats were labeled with 15N as previously described19, 70. The labeled rats at p45 were sacrificed using halothane and the brains were quickly removed and then frozen with liquid nitrogen. Eight 15N labeled whole brains were homogenized together in buffer H (4mM Hepes, 0.32M sucrose) and protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN ). Prior to any mixing with 14N brain tissue, we determined the 15N labeling efficiency to be 95% using a previous described method70.

Brain tissue fractionation

At four postnatal time points (p1, p10, p20, and p45,) Sprague-Dawley rats were sacrificed using halothane and the brains were quickly removed and dissected, and then frozen with liquid nitrogen. For p1 and p10 rats, brains from 3 litters were dissected; for p20 rats, brains from 2 litters were dissected; and for p45 rats, 10 brains were dissected. For each dissection, the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum were isolated. For each time point, each brain region was pooled and homogenized together in buffer H and protease inhibitors. After a BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), each 25mg of pooled homogenate was mixed with 25mg of 15N labeled rat brain homogenate, and fractionated as previously reported71. Briefly, the 50mg mixture was centrifuged at 800 × g at 15 minutes at 4°C. The pellet is described in this study as the nuclear fraction. The supernant was then centrifuged at 10, 000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in buffer H and fractionated using a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of 0.85, 1.0, and 1.2M sucrose at 120,000 × g for 2 hours at 4°C. After centrifugation, the synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions were isolated at the 1.0/1.2 interface and the pellet respectively. In figure 7b, the growth cone fraction was also isolated at the 0.85/1.0 interface. Each fraction was homogenized in buffer H, then centrifuged at 100, 000 × g for 15min. The pellets were resuspended in buffer H and frozen at −80°C until digestion. Each fraction was analyzed twice by MudPIT resulting two analyses for each time point and brain region. For western blot analyses (Figure 6 and S5), the identical protocol was followed except there was no 15N brain tissue added and a total of 50mg of 14N tissue was used. In addition, a different group of rats were used for the western blot analysis from the MS analysis. Western blot analysis confirmed enrichment of the organelles at each developmental time point (Figure S5).

Protein Digestion

After a BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), one-hundred micrograms of each 14N/15N protein fraction was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The synaptosomal pellets were digested with proteinase K as previously described72. The mitochondrial pellets were solubilized with 50μl of 5X invitrosol(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 8M urea, and next the samples were alkylated and reduced as previously described 73. Then, 200μl of 100mM Tris, pH 8.5, and 2mM CaCl2 was added to each sample and then digested with 4μg of trypsin overnight in a 37 °C shaking incubator. After the digestion, the samples were frozen at −80 °C. Prior to mass spectrometry analysis, the samples were thawed, 5% formic acid was added, and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g at room temperature for 30 min. The supernatants were transferred to a new eppendorf tube and loaded on a MudPIT column.

Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT)

For a single analysis, 100μg of the digested sample was pressure-loaded onto a fused silica capillary desalting column containing 2cm of 10 μm Jupiter material (Phenomenex, Ventura, CA) followed by 2cm of 3 cm 5-μm Partisphere strong cation exchanger (SCX) (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) into a 250-μm i.d capillary fritted with immobilized Kasil 1624 (PQ Corperation, Valley forge, PA) following the SCX. After the sample was loaded, the desalting column was washed with buffer containing 95% water, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid. Then, a 100-μm i.d capillary with a 5-μm pulled tip packed with 15 cm 4-μm Jupiter material (Phenomenex, Ventura, CA) was attached to a ZDV union and the entire split-column (desalting column–union–analytical column) was placed inline with an Eskigent Nano HPLC pump (Eksigent Technologies, Dublin, CA) and analyzed using a modified 12-step separation described previously28. As peptides eluted from the microcapillary column, they were electrosprayed directly into an LTQ-Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, Palo Alto, CA) programmed as previously described 74.

Interpretation of Tandem mass spectra

Both MS1 and MS2 (tandem mass spectra) were extracted from the XCalibur data system format (.RAW) into MS1 and MS2 formats75 using in house software (RAW_Xtractor). At this point, the MS1 and MS2 files for duplicate analyses were combined. Tandem mass spectra were interpreted by SEQUEST76, which was parallelized on a Beowulf cluster of 100 computers77 and results were filtered, sorted, and displayed using the DTASelect2 program using a decoy database strategy78. For each MudPIT analysis, the protein false positive rate was < 1%. Specifically, the distribution of SEQUEST values (i.e. Xcorr, DeltaCN, and DeltaMass) for (a) direct and (b) decoy database hits were obtained, and the two subsets were separated by quadratic discriminant analysis. Outlier points in the two distributions (for example, matches with very low Xcorr but very high DeltCN) were discarded. Full separation of the direct and decoy subsets is not generally possible; therefore, the discriminant score was set such that a false positive rate of 5% was determined based on the number of accepted decoy database peptides. In addition, a minimum sequence length of 7 amino acid residues was required, and each protein on the list was supported by at least two peptide identifications. These additional requirements - especially the latter - resulted in the elimination of most decoy database and false positive hits, as these tended to be overwhelmingly present as proteins identified by single peptide matches. After this last filtering step, the false identification rate was reduced to below 1%. Searches were performed against the rat International Protein Index (IPI) database (IPI, v3.05). The 14N and 15N searches were performed separately and combined after the Census analysis.

Quantitative Analysis using Census

After filtering the results from SEQUEST using DTASelect2, ion chromatograms were generated using an updated version of a program previously written in our lab 79. This software, called Census80, is available from the authors for individual use and evaluation through an Institutional Software Transfer Agreement (see http://fields.scripps.edu/census for details).

First, the elemental compositions and corresponding isotopic distributions for both the unlabeled and labeled peptides were calculated and this information was then used to determine the appropriate m/z range from which to extract ion intensities, which included all isotopes with greater than 5% of the calculated isotope cluster base peak abundance. MS1 files were used to generate chromatograms from the m/z range surrounding both the unlabeled and labeled precursor peptides.

Census calculates peptide ion intensity ratios for each pair of extracted ion chromatograms. The heart of the program is a linear least squares correlation that is used to calculate the ratio (i.e., slope of the line) and closeness of fit (i.e., correlation coefficient (r)) between the data points of the unlabeled and labeled ion chromatograms. Census allows users to filter peptide ratio measurements based on a correlation threshold because the correlation coefficient (values between zero and one) represents the quality of the correlation between the unlabeled and labeled chromatograms, and can be used to filter out poor quality measurements. In this study, only peptide ratios with correlation values greater than 0.5 were used for further analysis. In addition, Census provides an automated method for detecting and removing statistical outliers. In brief, standard deviations are calculated for all proteins using their respective peptide ratio measurements. The Grubbs test (p < 0.01) is then applied to remove outlier peptides. The outlier algorithm is used only when there are more than three peptides found in the same proteins, because the algorithm becomes unreliable for a small number of measurements. When we observed splice isoforms that possessed the identical protein 14N/15N averages, the protein name was altered to the most basic name and only one entry was allowed in our analysis.

For the singleton analysis in the identification of novel regulators of neurodevelopment, we required the 14N/15N ratio to be greater than 10.0 and the threshold score to be greater than 0.5. The threshold score ranges from zero to one and represents the quality of the singleton analysis with one being the most stringent. It is possible that the corresponding 15N peptide is not detected, because the 14N identification was incorrect. To reduce these false positives, we required a protein in this analysis to possess at least three singleton peptides for it to be considered valid. Another potential complication is that the internal standard was total homogenate from labeled brains. Therefore, it is possible the identified singleton protein could just be a singleton protein in the p1 sample, because the protein is highly enriched in a particular brain region compared to total homogenate and not due to an up-regulation in p1 14N compared to p45 15N. To eliminate this possibility, singleton analysis for each brain region was also performed on the p20 and p45 samples. Any singleton proteins common to the p1, p20 and p45 analyses were not considered potential regulators of neurodevelopment.

Statistical Analysis

Before statistical analysis, the median of the natural log of the ratios from each Census analysis was calculated, and then, all the medians were shifted to zero81. The calculated medians were very similar, and it was assumed any shift in the median was due to human error in the protein mixing. For statistical analysis, each 14N/15N peptide ratio for a given protein was considered one measurement or N=1 and only proteins were analyzed that had two or more quantified peptides The average of the quantified peptides and their standard deviation were calculated by Census for each protein for the one-way ANOVA analysis. The analysis was only performed on proteins that were quantitated in all four developmental stages within a brain region or proteins that were quantitated in all three brain regions at a given time point. If protein changes had a p value < 0.05, then a Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was performed. Proteins that passed ANOVA, but did not pass the Bonferroni’s test were not reported. All statistical tests were performed using Prism 4 Software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Ingenuity software was employed to determine statistically significant association with functions and diseases.

Ingenuity Analysis

Ingenuity software was employed to determine the functional group and neurological disorders associated with a particular dataset 82. For a significant association with a function or disease, we required the p-value to be < 1 ×10−6. The p-value measures how likely the observed association between a specific function or disease and our dataset would be if it was only due to random chance. The two major factors in this calculation are the number of proteins annotated to specific function or disease from our dataset and the total number of proteins annotated to the function or disease in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. For determining the functional differences and networks between brain regions, the input was the statistically significant changes between brain regions. We also included proteins that were identified by six peptides in one brain region and not identified in another brain region as. Linking protein abundance to all or none identifications of low abundant proteins has previously been employed successfully83. Ingenuity was employed to generate the p45 synaptic network (Figure 4D) and the ETC networks (Figure 5D and E) and only direct relationships were allowed into the network. For the synaptic network, some proteins have been localized to both the presynapse and the postsynapse in the literature, but to simplify the network, only one localization was chosen.

Identification of Novel Regulators of Neurodevelopment

Twenty-eight annotated proteins were observed to have a significantly greater expression in p1 compared to p45 in at least one brain region. If a protein is unique to or highly expressed at p1, then the corresponding 15N peptide from the p45 labeled brain may not be detected by the mass spectrometer due to its limited dynamic range84. This situation is termed a singleton peptide 85. Since a 14N/15N ratio is not generated, these peptides would have been excluded from our statistical analyses. Census, however, is able to search for these singleton peptides in the data80, and we identified twenty-one annotated singleton proteins. To further identify regulators of neurodevelopment spectral counts (SC) were employed to analyze protein expression between the p1 and p45 samples86. Thirty-three annotated proteins were identified that possessed a five-fold greater SC in p1 compared to p45, and nine of these proteins were also determined by Census to be up-regulated in the p1 brain. This analysis was performed using only the 14N identifications. To identify proteins that were up-regulated in p1 compared to p45 (Table S17), we first normalized the spectral counts of each protein by dividing by the total number spectra identified in the analysis in which the protein was identified. For a protein to be considered to be up-regulated in the p1 sample, we required a five-fold increase in the normalized spectra count in the p1 sample compared to the p45 sample within a brain region. Proteins that were up-regulated in p1 by this method, but disagreed with the statistical analysis using Census were discarded.

Western Blot Analysis

For Figure 6, the samples were prepared in the following manner. The hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum was dissected from three litters of p1and ten p45 rats for synaptosomal preparations following the identical synaptosomal protocol for the MS analysis except 15N brain tissue was not added and the total 14N input was 50mg. These rats were not same rats employed for the MS analysis. After a BCA protein assay, the synaptosomal fractions were prepared in 5X loading buffer and reducing agent (ThermoScientific, Rockford, IL), separated by 8–16 % Tris-Glycine gel or 3–8% Tris-acetate gel(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were processed as previously described87. Membranes were probed with the following antibodies: rabbit GluR 2/3 (Upstate Biotechnology, Temecula, CA), CAND1 (Santa Cruz Biotecnology, Santa Cruz, CA), LIMPII (a gift from Ignacio Sandoval of Instituto de Salud Carlos III ), CRIP (a gift from Dr. Wil-Jan Hendriks at University of Nijmegen), Tom20 (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), COX1(Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), RabGDI(a gift from Dr. William Balch at The Scripps Research Institute), DHC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), LRP157(a gift from Dr. Mark A. Schumacher at UCSF), and AUF1(Upstate Biotechnology, Temecula, CA). All secondary antibodies were conjugated with HRP and purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). For a particular antibody, two immunoblots were performed each consisting of p1 and p45 samples from the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum. The immunoreactivity of each antibody was visualize by Supersignal West Pico or Femto reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and measured by PhotoShop (Adobe Systems) on two different immunoblots. Briefly, the scanned image of an immunoblot was first inverted, and then the threshold was adjusted until the least intense immunoreactive band was barely visible. The mean pixel intensity was recorded for each band on the image employing a rectangular cursor of identical dimensions for each band.

Supplementary Material

Within each fraction (synaptosomal – Hippocampus (A), Cerebellum (B), Cortex (C) and mitochondrial - Hippocampus (D), Cerebellum (E), Cortex (F)), the magnitude of the changes observed in the p1 vs. p10 comparison was significantly greater than the p20 vs. p45 comparison. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The most significant (p < 1.0 × 10−6) functional group annotated to the proteins that clustered within the same temporal pattern. The y-axis is the -log(p-value) and the x-axis is the temporal pattern labeled by its peak expression during development. No functional group was significant for the proteins that decrease with age in the synaptosomal fraction.

The data from the SOM analysis is plotted by the percentage of proteins in the in each temporal trend that was associated with a neurological disorder determined by Ingenuity. Although a majority of the proteins exhibited an increase in expression with age, a similar percentage of proteins in each temporal pattern were associated with neurological diseases in the synaptosomal fraction. In the mitochondrial fraction, a majority of disease associated proteins exhibited an increase in expression with age. In the synaptosomal fraction, proteins were identified that associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. In the mitochondrial fraction, proteins associated with Leigh’s syndrome and Huntington’s disease were found. The proteins identified in this analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 16.

Proteins that differed between brain regions at each time point were annotated into functional groups and each functional group was assigned a p-value which measures how likely the observed association between a specific function and our dataset would be if it was only due to random chance. The three most frequent and significant (p < 1×10e−6) protein functional groups in the synaptosomal fraction were synaptic transmission (A), ion transport (B), and neurite outgrowth(C). The first brain region in the comparison indicates that the proteins are up-regulated compared to the second brain region. For example, proteins that were up-regulated in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus (e.g. Cb_H) were significantly associated with synaptic transmission at p45, but at the other time points no function was significantly associated with the proteins up-regulated in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus. D, The most frequent and significant (p < 1×10e−6) protein functional group was the metabolism of ATP in the mitochondrial fraction.

Brain tissue from rats at p1, p10, p20, and p45 was fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient. Western blot analysis of the total homogenate (1), synaptosomal fraction (2), and the mitochondrial fraction (3) from each time point was probed with a synaptic marker (synaptophysin) and a mitochondrial marker (Complex II subunit 30kDa). The synaptophysin immunoreactivity was only observed in the synaptosomal fraction at all the time points verifying the enrichment of synapses in this fraction. Similarly, the mitochondrial marker was observed in the mitochondrial fraction and not the total homogenate confirming an enrichment of mitochondria. Consistent with mitochondria localized to the synapse, 30kDa immunoreactivity was also observed in this fraction. In contrast, immunoreactivity for the translational protein, elongation factor 1 alpha (eEF1A), was abundantly observed in the total homogenate and to a lesser extent in the synaptosomal fraction as described in the literature.

The protein identifications from the synaptosomal fraction.

The protein identifications from the mitochondria fraction

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal cerebellar proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal hippocampal proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal cortical proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in mitochondrial cerebellar proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in mitochondrial hippocampal proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in mitochondrial cortical proteome during development

SOM analysis of the significantly altered proteins during development in the synaptosomal fraction

SOM analysis of the significantly altered proteins during development in the mitochondrial fraction

Proteins associated with Neurological Disorders

Statistically significant changes in p45 synaptosomal proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p20 synaptosomal proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p10 synaptosomal proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p1 synaptosomal proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p45 mitochondrial proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p20 mitochondrial proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p10 mitochondrial proteome between brain regions

Statistically significant changes in p1 mitochondrial proteome between brain regions

Proteins in the synaptic network.

Regulators of Neuronal Development

References for Supplementary Table 37

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from NIH grants R01 MH067880 and P41 RR011823.

References

- 1.Amir RE, et al. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mineur YS, Sluyter F, de Wit S, Oostra BA, Crusio WE. Behavioral and neuroanatomical characterization of the Fmr1 knockout mouse. Hippocampus. 2002;12:39–46. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roubertoux PL, Kerdelhue B. Trisomy 21: from chromosomes to mental retardation. Behav Genet. 2006;36:346–354. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olney JW. Fetal alcohol syndrome at the cellular level. Addict Biol. 2004;9:137–149. doi: 10.1080/13556210410001717006. discussion 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirulli F, et al. Early life stress as a risk factor for mental health: role of neurotrophins from rodents to non-human primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wicks S, Hjern A, Gunnell D, Lewis G, Dalman C. Social adversity in childhood and the risk of developing psychosis: a national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1652–1657. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardno AG, Gottesman Twin studies of schizophrenia: from bow-and-arrow concordances to star wars Mx and functional genomics. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebat J, Levy DL, McCarthy SE. Rare structural variants in schizophrenia: one disorder, multiple mutations; one mutation, multiple disorders. Trends Genet. 2009;25:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marenco S, Weinberger DR. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: following a trail of evidence from cradle to grave. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:501–527. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torkamani A, Dean B, Schork NJ, Thomas EA. Coexpression network analysis of neural tissue reveals perturbations in developmental processes in schizophrenia. Genome Res. 2010;20:403–412. doi: 10.1101/gr.101956.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glessner JT, et al. Strong synaptic transmission impact by copy number variations in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10584–10589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000274107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilmatre A, et al. Recurrent rearrangements in synaptic and neurodevelopmental genes and shared biologic pathways in schizophrenia, autism, and mental retardation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:947–956. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Dushlaine C, et al. Molecular pathways involved in neuronal cell adhesion and membrane scaffolding contribute to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder susceptibility. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:286–292. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:434–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mody M, et al. Genome-wide gene expression profiles of the developing mouse hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8862–8867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141244998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stead JD, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the developing rat brain reveals that the most dramatic regional differentiation in gene expression occurs postpartum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:345–353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris LW, et al. Gene expression in the prefrontal cortex during adolescence: implications for the onset of schizophrenia. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CC, MacCoss MJ, Howell KE, Matthews DE, Yates JR., 3rd Metabolic labeling of mammalian organisms with stable isotopes for quantitative proteomic analysis. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4951–4959. doi: 10.1021/ac049208j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClatchy DB, Dong MQ, Wu CC, Venable JD, Yates JR., 3rd 15N metabolic labeling of mammalian tissue with slow protein turnover. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2005–2010. doi: 10.1021/pr060599n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irwin SA, Galvez R, Greenough WT. Dendritic spine structural anomalies in fragile-X mental retardation syndrome. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoghbi HY. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: meeting at the synapse? Science. 2003;302:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1089071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belichenko PV, Kleschevnikov AM, Salehi A, Epstein CJ, Mobley WC. Synaptic and cognitive abnormalities in mouse models of Down syndrome: exploring genotype-phenotype relationships. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:329–345. doi: 10.1002/cne.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middleton FA, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Gene expression profiling reveals alterations of specific metabolic pathways in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2718–2729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02718.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ben-Shachar D, Karry R. Neuroanatomical pattern of mitochondrial complex I pathology varies between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erecinska M, Cherian S, Silver IA. Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:397–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link AJ, et al. Direct analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:676–682. doi: 10.1038/10890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng J, et al. Rac GTPases control axon growth, guidance and branching. Nature. 2002;416:442–447. doi: 10.1038/416442a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumas TC. Late postnatal maturation of excitatory synaptic transmission permits adult-like expression of hippocampal-dependent behaviors. Hippocampus. 2005;15:562–578. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maness PF, Schachner M. Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Adamo P, et al. Mutations in GDI1 are responsible for X-linked non-specific mental retardation. Nat Genet. 1998;19:134–139. doi: 10.1038/487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geschwind DH, Hockfield S. Identification of proteins that are developmentally regulated during early cerebral corticogenesis in the rat. J Neurosci. 1989;9:4303–4317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04303.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goshima Y, Nakamura F, Strittmatter P, Strittmatter SM. Collapsin-induced growth cone collapse mediated by an intracellular protein related to UNC-33. Nature. 1995;376:509–514. doi: 10.1038/376509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stumpo DJ, Bock CB, Tuttle JS, Blackshear PJ. MARCKS deficiency in mice leads to abnormal brain development and perinatal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:944–948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerlund N, et al. Phosphorylation of SCG10/stathmin-2 determines multipolar stage exit and neuronal migration rate. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:305–313. doi: 10.1038/nn.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aghajanian GK, Bloom FE. The formation of synaptic junctions in developing rat brain: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Brain Res. 1967;6:716–727. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(67)90128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erecinska M, Silver IA. ATP and brain function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:2–19. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davey GP, Peuchen S, Clark JB. Energy thresholds in brain mitochondria. Potential involvement in neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12753–12757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown MR, Sullivan PG, Geddes JW. Synaptic mitochondria are more susceptible to Ca2+overload than nonsynaptic mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11658–11668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young KW, Bampton ET, Pinon L, Bano D, Nicotera P. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling in hippocampal neurons. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CW, Peng HB. Mitochondrial clustering at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction during presynaptic differentiation. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:522–536. doi: 10.1002/neu.20245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villa RF, Gorini A, Geroldi D, Lo Faro A, Dell’Orbo C. Enzyme activities in perikaryal and synaptic mitochondrial fractions from rat hippocampus during development. Mech Ageing Dev. 1989;49:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(89)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leong SF, Lai JC, Lim L, Clark JB. The activities of some energy-metabolising enzymes in nonsynaptic (free) and synaptic mitochondria derived from selected brain regions. J Neurochem. 1984;42:1306–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genova ML, et al. Decrease of rotenone inhibition is a sensitive parameter of complex I damage in brain non-synaptic mitochondria of aged rats. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:467–469. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00638-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almeida A, et al. Postnatal development of the complexes of the electron transport chain in synaptic mitochondria from rat brain. Dev Neurosci. 1995;17:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000111289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong-Riley MT. Cytochrome oxidase: an endogenous metabolic marker for neuronal activity. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:94–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandrasekaran K, et al. Differential expression of cytochrome oxidase (COX) genes in different regions of monkey brain. J Neurosci Res. 1992;32:415–423. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490320313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macaskill AF, et al. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollenbeck PJ, Saxton WM. The axonal transport of mitochondria. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:5411–5419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stowers RS, Megeath LJ, Gorska-Andrzejak J, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron. 2002;36:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo X, et al. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron. 2005;47:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verstreken P, et al. Synaptic mitochondria are critical for mobilization of reserve pool vesicles at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 2005;47:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Husi H, Ward MA, Choudhary JS, Blackstock WP, Grant SG. Proteomic analysis of NMDA receptor-adhesion protein signaling complexes. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:661–669. doi: 10.1038/76615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordan BA, et al. Identification and verification of novel rodent postsynaptic density proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:857–871. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400045-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peng J, et al. Semiquantitative proteomic analysis of rat forebrain postsynaptic density fractions by mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez E, et al. Targeted tandem affinity purification of PSD-95 recovers core postsynaptic complexes and schizophrenia susceptibility proteins. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:269. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoch S, et al. SNARE function analyzed in synaptobrevin/VAMP knockout mice. Science. 2001;294:1117–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1064335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Washbourne P, et al. Genetic ablation of the t-SNARE SNAP-25 distinguishes mechanisms of neuroexocytosis. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ. Synaptic pathology in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorders. A review and a Western blot study of synaptophysin, GAP-43 and the complexins. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DiProspero NA, et al. Early changes in Huntington’s disease patient brains involve alterations in cytoskeletal and synaptic elements. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:517–533. doi: 10.1007/s11068-004-0514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Basso M, et al. Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Proteomics. 2004;4:3943–3952. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tannenberg RK, Scott HL, Tannenberg AE, Dodd PR. Selective loss of synaptic proteins in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for an increased severity with APOE varepsilon4. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao PJ, et al. Defects in expression of genes related to synaptic vesicle trafficking in frontal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;12:97–109. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Masliah E, et al. Altered expression of synaptic proteins occurs early during progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;56:127–129. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y, et al. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abeliovich A, et al. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron. 2000;25:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gray LJ, Dean B, Kronsbein HC, Robinson PJ, Scarr E. Region and diagnosis-specific changes in synaptic proteins in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bragina L, Giovedi S, Barbaresi P, Benfenati F, Conti F. Heterogeneity of glutamatergic and GABAergic release machinery in cerebral cortex: analysis of synaptogyrin, vesicle-associated membrane protein, and syntaxin. Neuroscience. 2010;165:934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McClatchy DB, Liao L, Park SK, Venable JD, Yates JR. Quantification of the synaptosomal proteome of the rat cerebellum during post-natal development. Genome Res. 2007;17:1378–1388. doi: 10.1101/gr.6375007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gray EG, Whittaker VP. The isolation of nerve endings from brain: an electron-microscopic study of cell fragments derived by homogenization and centrifugation. J Anat. 1962;96:79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu CC, MacCoss MJ, Howell KE, Yates JR., 3rd A method for the comprehensive proteomic analysis of membrane proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:532–538. doi: 10.1038/nbt819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen EI, McClatchy D, Park SK, Yates JR., Iii Comparisons of Mass Spectrometry Compatible Surfactants for Global Analysis of the Mammalian Brain Proteome. Anal Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1021/ac800606w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Venable JD, Wohlschlegel J, McClatchy DB, Park SK, Yates JR., 3rd Relative quantification of stable isotope labeled peptides using a linear ion trap-Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2007;79:3056–3064. doi: 10.1021/ac062054i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDonald WH, et al. MS1, MS2, and SQT- Three Unified, Compact, and Easily Parsed File Formats for the Storage of Shotgun Proteomic Spectra and Identifications. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2162–2168. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR., III An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sadygov RG, et al. Code developments to improve the efficiency of automated MS/MS spectra interpretation. Journal of Proteome Research. 2002;1:211–215. doi: 10.1021/pr015514r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.MacCoss MJ, Wu CC, JRY A correlation algorithm for the automated analysis of quantitative ‘shotgun’ proteomics data. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75:6912–6921. doi: 10.1021/ac034790h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park SK, Venable JD, Xu T, Yates JR., 3rd A quantitative analysis software tool for mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat Methods. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ting L, et al. Normalization and statistical analysis of quantitative proteomics data generated by metabolic labeling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2227–2242. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800462-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Calvano SE, et al. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature. 2005;437:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature03985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chu DS, et al. Sperm chromatin proteomics identifies evolutionarily conserved fertility factors. Nature. 2006;443:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature05050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Corthals GL, Wasinger VC, Hochstrasser DF, Sanchez JC. The dynamic range of protein expression: a challenge for proteomic research. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1104–1115. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000401)21:6<1104::AID-ELPS1104>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liao L, et al. Quantitative analysis of brain nuclear phosphoproteins identifies developmentally regulated phosphorylation events. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4743–4755. doi: 10.1021/pr8003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR., 3rd A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berkeley JL, Levey AI. Muscarinic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2000;75:487–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Within each fraction (synaptosomal – Hippocampus (A), Cerebellum (B), Cortex (C) and mitochondrial - Hippocampus (D), Cerebellum (E), Cortex (F)), the magnitude of the changes observed in the p1 vs. p10 comparison was significantly greater than the p20 vs. p45 comparison. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The most significant (p < 1.0 × 10−6) functional group annotated to the proteins that clustered within the same temporal pattern. The y-axis is the -log(p-value) and the x-axis is the temporal pattern labeled by its peak expression during development. No functional group was significant for the proteins that decrease with age in the synaptosomal fraction.

The data from the SOM analysis is plotted by the percentage of proteins in the in each temporal trend that was associated with a neurological disorder determined by Ingenuity. Although a majority of the proteins exhibited an increase in expression with age, a similar percentage of proteins in each temporal pattern were associated with neurological diseases in the synaptosomal fraction. In the mitochondrial fraction, a majority of disease associated proteins exhibited an increase in expression with age. In the synaptosomal fraction, proteins were identified that associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. In the mitochondrial fraction, proteins associated with Leigh’s syndrome and Huntington’s disease were found. The proteins identified in this analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 16.

Proteins that differed between brain regions at each time point were annotated into functional groups and each functional group was assigned a p-value which measures how likely the observed association between a specific function and our dataset would be if it was only due to random chance. The three most frequent and significant (p < 1×10e−6) protein functional groups in the synaptosomal fraction were synaptic transmission (A), ion transport (B), and neurite outgrowth(C). The first brain region in the comparison indicates that the proteins are up-regulated compared to the second brain region. For example, proteins that were up-regulated in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus (e.g. Cb_H) were significantly associated with synaptic transmission at p45, but at the other time points no function was significantly associated with the proteins up-regulated in the cerebellum compared to the hippocampus. D, The most frequent and significant (p < 1×10e−6) protein functional group was the metabolism of ATP in the mitochondrial fraction.

Brain tissue from rats at p1, p10, p20, and p45 was fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient. Western blot analysis of the total homogenate (1), synaptosomal fraction (2), and the mitochondrial fraction (3) from each time point was probed with a synaptic marker (synaptophysin) and a mitochondrial marker (Complex II subunit 30kDa). The synaptophysin immunoreactivity was only observed in the synaptosomal fraction at all the time points verifying the enrichment of synapses in this fraction. Similarly, the mitochondrial marker was observed in the mitochondrial fraction and not the total homogenate confirming an enrichment of mitochondria. Consistent with mitochondria localized to the synapse, 30kDa immunoreactivity was also observed in this fraction. In contrast, immunoreactivity for the translational protein, elongation factor 1 alpha (eEF1A), was abundantly observed in the total homogenate and to a lesser extent in the synaptosomal fraction as described in the literature.

The protein identifications from the synaptosomal fraction.

The protein identifications from the mitochondria fraction

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal cerebellar proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal hippocampal proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in synaptosomal cortical proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in mitochondrial cerebellar proteome during development

Statistically significant changes in mitochondrial hippocampal proteome during development