Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections each resulted in approximately 60 US hospitalizations per 100000 persons annually during 1993–2008. RSV was associated with 16 times more hospitalizations than influenza in children aged <1 year, whereas influenza caused 8 times more hospitalizations in persons aged >5 years.

Abstract

Background. Age-specific comparisons of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalization rates can inform prevention efforts, including vaccine development plans. Previous US studies have not estimated jointly the burden of these viruses using similar data sources and over many seasons.

Methods. We estimated influenza and RSV hospitalizations in 5 age categories (<1, 1–4, 5–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years) with data for 13 states from 1993–1994 through 2007–2008. For each state and age group, we estimated the contribution of influenza and RSV to hospitalizations for respiratory and circulatory disease by using negative binomial regression models that incorporated weekly influenza and RSV surveillance data as covariates.

Results. Mean rates of influenza and RSV hospitalizations were 63.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], 37.5–237) and 55.3 (95% CI, 44.4–107) per 100000 person-years, respectively. The highest hospitalization rates for influenza were among persons aged ≥65 years (309/100000; 95% CI, 186–1100) and those aged <1 year (151/100000; 95% CI, 151–660). For RSV, children aged <1 year had the highest hospitalization rate (2350/100000; 95% CI, 2220–2520) followed by those aged 1–4 years (178/100000; 95% CI, 155–230). Age-standardized annual rates per 100000 person-years varied substantially for influenza (33–100) but less for RSV (42–77).

Conclusions. Overall US hospitalization rates for influenza and RSV are similar; however, their age-specific burdens differ dramatically. Our estimates are consistent with those from previous studies focusing either on influenza or RSV. Our approach provides robust national comparisons of hospitalizations associated with these 2 viral respiratory pathogens by age group and over time.

Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are important pathogens responsible for substantial morbidity and mortality almost every US winter. Influenza- and RSV-associated illnesses are difficult to count because the symptoms associated with infection are nonspecific, laboratory testing is not routine, and influenza and RSV codes are listed incompletely in administrative medical records. Recent prospective studies have enrolled persons seeking care for respiratory conditions and tested them for infection [1–6]; however, such studies are resource intensive and rarely conducted in multiple sites or over seasons. In contrast, modeling approaches using broad disease outcomes have been used to estimate the burden of influenza and RSV in large populations and over long periods [7–13], but these approaches generally focus on a single pathogen. A better understanding of the relative burdens of influenza and RSV in all age groups is important for prevention efforts, particularly to guide deliberations about the expansion of existing vaccination recommendations and the development of new vaccines.

Annual influenza and RSV epidemics often overlap in temperate regions [12, 14], increasing the difficulty of modeling their effects, although their age-specific burdens do differ. Influenza is responsible for high rates of morbidity and mortality among older adults [7, 8, 10–13], whereas RSV has long been recognized as the most important respiratory viral pathogen in young children [4–6, 15, 16]. However, there is debate about the relative impact of influenza and RSV infections, particularly among adults aged ≥65 years [2]. A US study that jointly assessed influenza and RSV mortality estimated that 13.8 influenza- and 4.3 RSV-associated deaths occurred per 100000 persons annually during 1990–1999 [12]. This study also suggested that mortality associated with both influenza and RSV circulation disproportionately affected older adults [12]. Another US study estimated that influenza was responsible for 88 hospitalizations per 100000 persons from 1979 through 2001 [11], but it did not provide burden estimates for infants or estimates of RSV-associated hospitalizations. Using a 1% sample of all US hospitalizations, Holman et al estimated that 2740 RSV hospitalizations per 100000 infants occur annually [17]. Using laboratory-confirmed diagnoses, Fry et al [3] estimated 1087 RSV hospitalizations per 100000 infants occurred annually in rural Thailand. Other studies focused on US children aged <5 years have found that the influenza burden is lower than that of RSV in this age group [4–6].

We sought to estimate jointly overall and age-specific US hospitalization rates for influenza and RSV infections during many respiratory virus seasons to fill a data gap. We used complete state hospital discharge databases representing approximately 40% of the US population.

METHODS

Hospitalization Data

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) is a set of databases and software developed through a federal-state-industry partnership and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [18]. Weekly statewide hospital discharge data were obtained from HCUP state inpatient databases (SIDs), which contained information on all hospitalizations of >24 hours. The number of states contributing to SIDs has grown from 8 in 1988 to 40 in 2008. We used data from 13 states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington, and Wisconsin) that provided complete weekly records from 1993 through 2008. We analyzed hospitalizations in 5 age categories (<1, 1–4, 5–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years) based on expanding influenza vaccination recommendations from the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [19] and past studies. Annual population estimates for each state and age group were obtained from the US Bureau of the Census for the years 1993–2008 [20].

Viral Surveillance Data

We used viral data from 15 seasons, with each season starting in July and ending the next June. During 1993–1994 through 2007–2008, we obtained from 50–75 US laboratories the number of influenza tests performed and the number of positive tests by type/subtype each week [21]. Specimens reported as influenza A without subtype information were assigned as H1N1 or H3N2 by the ratio that each virus represented among influenza A viruses subtyped during each season. Weekly RSV data were reported for these seasons from 69–89 laboratories in 38–47 states; weekly numbers of specimens tested for RSV by antigen detection and viral isolation methods and numbers of positive results were obtained [22].

Estimating Influenza- and RSV-Associated Hospitalization Rates

Age- and state-specific negative binomial regression models were fit to weekly primary respiratory and circulatory hospitalizations (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] [23] codes 390–519), after excluding hospitalizations coded for influenza (ICD-9-CM codes 487.*) or RSV bronchiolitis or RSV pneumonia (ICD-9-CM codes 466.11, and 480.1, respectively). We assumed that the latter hospitalizations were all associated with influenza or RSV infections and thus should not be used for modeling. Covariates for the standardized proportion of specimens testing positive each week for H1N1, H3N2, B, and RSV each week in the 4 US census regions were included in the models (see Supplemental Materials).

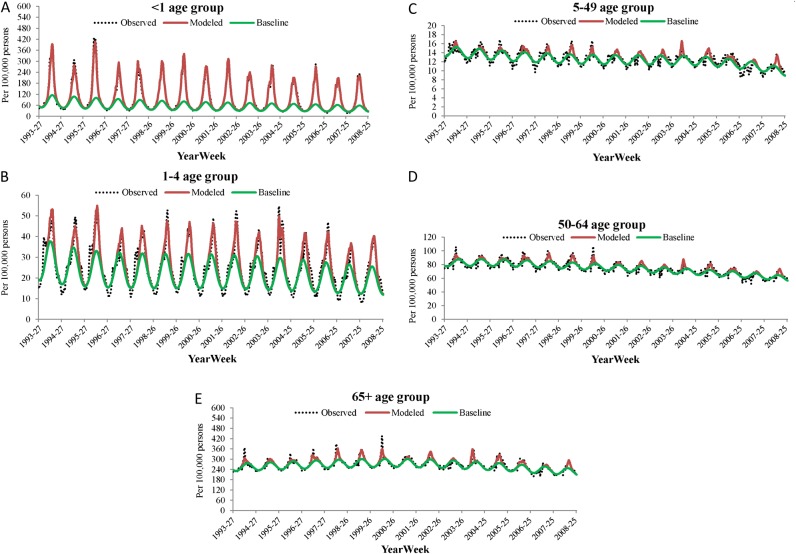

To estimate excess hospitalizations associated with influenza and RSV, we subtracted predicted hospitalizations from a full model incorporating all viral terms from an expected baseline, where the baseline represented a model in which a viral covariate was set to 0 (Figure 1). The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated with the model variance for the predicted values from regression models. We summed the CIs for each weekly estimate to make annual estimates. A similar approach has been used in previous studies [9, 13]; it assumes there was no uncertainty in the sum of the hospitalizations that were specifically coded for influenza and RSV. Thus, although the databases used included all hospital discharges for each of the participating states, our approach may underestimate the width of the true CI.

Figure 1.

Weekly observed, modeled, and baseline rates of respiratory or circulatory hospitalization rates by age group.

The number of weekly influenza-associated hospitalizations for each state was the sum of hospitalizations with an ICD-9-CM influenza code listed and the model estimate made with hospitalizations for respiratory and circulatory disease that did not have an influenza code listed in the hospitalization record. The RSV-associated hospitalizations were estimated in an analogous manner. All models were stratified by state and age group. National age-specific rates of hospitalizations each season were estimated by summing state- and age-specific estimates of influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalizations in the 13 SID states divided by the total populations for each age group in the 13 SID states. To compare trends in overall influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalization rates, we used the direct standardization method with age-specific US 2000 census population estimates [20].

RESULTS

Hospitalization Data

During the 1993–1994 through the 2007–2008 respiratory virus seasons, annual means of 13.5 (range, 5.2–28.8) influenza-coded, 33.8 (range, 28.9–42.7) RSV-coded, and 2814.9 (range, 2439.5–3043.6) hospitalizations for respiratory and circulatory disease occurred per 100000 person-years in the 13 SID states (Table 1). The highest rates for influenza and respiratory and circulatory disease hospitalizations occurred among persons aged ≥65 years, and the lowest rates among persons aged 5–49 years. Rates for RSV hospitalizations were highest among children aged <1 year, followed by children aged 1–4 years, and were relatively low in the other 3 age groups.

Table 1.

ICD-9-CM–Coded Hospitalization Rates for Influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Respiratory and Circulatory Diagnoses

| Influenzaa (Any Listed) by Age Group, y | RSVb (Any Listed) by Age Group, y | Respiratory and Circulatoryc (Primary) by Age Group, y | ||||||||||||||||

| Season | <1 | 1–4 | 5–49 | 50–64 | ≥65 | All Ages | <1 | 1–4 | 5–49 | 50–64 | ≥65 | All Ages | <1 | 1–4 | 5–49 | 50–64 | ≥65 | All Ages |

| 1993–1994 | 50.6 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 14.5 | 49.6 | 13.3 | 1720.8 | 136.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 37.2 | 5468 | 1448 | 734 | 4362 | 13 496 | 2862 |

| 1994–1995 | 24.5 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 7.3 | 21.1 | 6.8 | 1347.8 | 129.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 29.7 | 5098 | 1326 | 722 | 4330 | 13 642 | 2862 |

| 1995–1996 | 43.9 | 9.0 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 23.3 | 8.3 | 1997.2 | 182.9 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 42.7 | 5829 | 1402 | 705 | 4328 | 13 809 | 2892 |

| 1996–1997 | 54.7 | 11.1 | 5.3 | 10.7 | 37.8 | 11.1 | 1534.1 | 98.1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 29.0 | 4920 | 1241 | 685 | 4323 | 14 420 | 2936 |

| 1997–1998 | 73.9 | 17.3 | 5.1 | 11.7 | 50.9 | 13.3 | 1902.1 | 117.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 35.1 | 5240 | 1348 | 676 | 4246 | 14 675 | 2971 |

| 1998–1999 | 65.1 | 14.2 | 5.1 | 13.3 | 50.7 | 13.2 | 2019.5 | 139.7 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 37.7 | 5365 | 1307 | 687 | 4291 | 15 117 | 3044 |

| 1999–2000 | 83.3 | 17.6 | 7.1 | 22.9 | 92.7 | 21.3 | 2085.7 | 133.5 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 37.6 | 5223 | 1308 | 655 | 4043 | 14 775 | 2932 |

| 2000–2001 | 51.5 | 12.3 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 13.9 | 6.4 | 1955.5 | 137.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 35.8 | 4972 | 1296 | 657 | 3957 | 14 744 | 2903 |

| 2001–2002 | 79.5 | 22.9 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 26.4 | 8.9 | 1894.9 | 136.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 35.0 | 4719 | 1267 | 632 | 3781 | 14 285 | 2808 |

| 2002–2003 | 55.9 | 14.3 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 10.0 | 5.2 | 1792.5 | 122.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 32.5 | 4554 | 1261 | 644 | 3715 | 13 825 | 2760 |

| 2003–2004 | 278.6 | 83.8 | 9.3 | 18.7 | 95.1 | 28.8 | 1751.9 | 136.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 32.9 | 4685 | 1336 | 669 | 3789 | 14 363 | 2872 |

| 2004–2005 | 106.5 | 25.2 | 5.9 | 16.4 | 87.9 | 19.8 | 1562.0 | 121.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 29.3 | 4093 | 1194 | 654 | 3693 | 13 958 | 2800 |

| 2005–2006 | 135.8 | 27.0 | 5.1 | 10.6 | 55.6 | 15.0 | 1631.4 | 121.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 30.4 | 3962 | 1150 | 624 | 3437 | 12 880 | 2624 |

| 2006–2007 | 100.7 | 22.6 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 21.5 | 8.8 | 1534.9 | 115.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 28.9 | 3620 | 991 | 535 | 3201 | 12 009 | 2440 |

| 2007–2008 | 167.5 | 34.7 | 8.1 | 18.4 | 84.3 | 22.9 | 1680.2 | 140.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 33.2 | 3838 | 1101 | 555 | 3250 | 12 192 | 2520 |

| Mean | 91.5 | 21.9 | 5.3 | 11.6 | 48.1 | 13.5 | 1760.7 | 131.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 33.8 | 4772 | 1265 | 656 | 3916 | 13 879 | 2815 |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Data are hospitalization rates per 100 000 person-years and represent summaries from 13 states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington, and Wisconsin) .

ICD-9-CM codes 487.*.

Including codes ICD-9-CM 466.11 for bronchiolitis RSV, ICD-9-CM 480.1 for pneumonia RSV, and ICD-9-CM 079.6 for other RSV diagnosis.

ICD-9-CM codes 390–519.

Influenza and RSV Laboratory Surveillance

A mean of 68716 specimens (range, 36615–116062) was tested annually for influenza (Table 2). A mean of 15.8% of specimens tested positive for influenza; by type and subtype, these proportions were 1.9%, 8.9%, and 3.0% for H1N1, H3N2, and B viruses, respectively. The annual mean number of specimens tested for RSV was 76316 (range, 27544–282639), with a mean of 13558 specimens (19.5%) testing positive for RSV each season.

Table 2.

Annual Respiratory Virus Surveillance Data for 1993–1994 Through 2007–2008 Seasons

| Influenza | RSV | |||||||||||

| Specimens | A(H1N1) Positive | A(H3N2) Positive | B Positive | Total Influenza Positive | Specimens | RSV Positive | ||||||

| Season | Tested | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | Tested | No. | % |

| 1993–1994 | 36 615 | 16 | 0.0 | 3484 | 9.5 | 35 | 0.1 | 3535 | 9.7 | 27 544 | 6415 | 23.3 |

| 1994–1995 | 40 023 | 61 | 0.2 | 2526 | 6.3 | 1032 | 2.6 | 3619 | 9.0 | 33 513 | 8364 | 25.0 |

| 1995–1996 | 38 275 | 1945 | 5.1 | 1241 | 3.2 | 727 | 1.9 | 3913 | 10.2 | 31 456 | 8215 | 26.1 |

| 1996–1997 | 40 436 | 4 | 0.0 | 3687 | 9.1 | 1456 | 3.6 | 5147 | 12.7 | 33 912 | 7764 | 22.9 |

| 1997–1998 | 46 403 | 14 | 0.0 | 5796 | 12.5 | 53 | 0.1 | 5863 | 12.6 | 34 733 | 7037 | 20.3 |

| 1998–1999 | 52 450 | 23 | 0.0 | 5187 | 9.9 | 2279 | 4.3 | 7489 | 14.3 | 36 903 | 7448 | 20.2 |

| 1999–2000 | 51 493 | 183 | 0.4 | 6762 | 13.1 | 66 | 0.1 | 7011 | 13.6 | 30 764 | 6448 | 21.0 |

| 2000–2001 | 48 339 | 3083 | 6.4 | 85 | 0.2 | 3233 | 6.7 | 6401 | 13.2 | 59 829 | 11 470 | 19.2 |

| 2001–2002 | 54 643 | 256 | 0.5 | 7020 | 12.8 | 1545 | 2.8 | 8821 | 16.1 | 50 106 | 9035 | 18.0 |

| 2002–2003 | 52 165 | 3058 | 5.9 | 1154 | 2.2 | 3297 | 6.3 | 7509 | 14.4 | 46 108 | 7571 | 16.4 |

| 2003–2004 | 82 265 | 2 | 0.0 | 16 318 | 19.8 | 171 | 0.2 | 16 491 | 20.0 | 75 487 | 12 520 | 16.6 |

| 2004–2005 | 88 265 | 23 | 0.0 | 11 262 | 12.8 | 4202 | 4.8 | 15 487 | 17.5 | 93 515 | 13 771 | 14.7 |

| 2005–2006 | 87 363 | 640 | 0.7 | 8648 | 9.9 | 2207 | 2.5 | 11 495 | 13.2 | 99 634 | 15 742 | 15.8 |

| 2006–2007 | 195 943 | 11 200 | 5.7 | 4878 | 2.5 | 5312 | 2.7 | 21 390 | 10.9 | 208 604 | 35 675 | 17.1 |

| 2007–2008 | 116 062 | 3796 | 3.3 | 11 462 | 9.9 | 7405 | 6.4 | 22 663 | 19.5 | 282 639 | 45 902 | 16.2 |

| Mean | 68 716 | 1620 | 1.9 | 5967 | 8.9 | 2201 | 3.0 | 9789 | 13.8 | 76 316 | 13 558 | 19.5 |

Abbreviation: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Estimates of Influenza- and RSV-Associated Hospitalizations

Mean annual influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalization rates were 63.5 (95% CI, 37.5–236.6) and 55.3 (95% CI, 44.4–106.7) per 100000 person-years, respectively (Table 3). Age-standardized annual rates varied substantially for influenza (33–100/100000 person-years) but less for RSV (42–77). Influenza hospitalization rates were highest among infants aged <1 year (151.0/100000 person-years; 95% CI, 105.3–659.6) and persons aged ≥65 years (309.1/100000 person-years; 95% CI, 186.0–1103.7). The RSV hospitalization rate in infants aged <1 year was 2345 per 100000 person-years (95% CI, 2219–2525), compared with 86.1 (95% CI, 37.3–326.2) for those aged ≥65 years. Influenza was associated with a mean of 8 times as many hospitalizations as RSV among persons aged ≥5 years. Respiratory syncytial virus was associated with 16 and 5 times as many hospitalizations as influenza among children aged <1 year and 1–4 years, respectively.

Table 3.

Estimated Influenza- and Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalization Rates by Negative Binomial Regression Models

| Aged <1 y | Aged 1–4 y | Aged 5–49 y | Aged 50–64 y | Aged ≥65 y | All Agesa | |||||||

| Season | Influenza | RSV | Influenza | RSV | Influenza | RSV | Influenza | RSV | Influenza | RSV | Influenza | RSV |

| 1993–1994b | 92.3 | 2802.0 | 14.7 | 206.4 | 12.1 | 2.2 | 55.6 | 16.2 | 234.9 | 100.7 | 47.6 | 65.9 |

| 1994–1995b | 49.5 | 2121.3 | 16.8 | 181.3 | 12.5 | 1.8 | 49.8 | 14.4 | 203.0 | 88.0 | 42.5 | 53.1 |

| 1995–1996 | 191.2 | 3150.7 | 23.6 | 260.4 | 13.6 | 2.6 | 42.8 | 19.9 | 166.6 | 124.5 | 40.0 | 77.4 |

| 1996–1997b | 93.4 | 2227.7 | 38.5 | 150.1 | 20.8 | 1.4 | 84.3 | 14.6 | 369.8 | 93.0 | 75.6 | 53.3 |

| 1997–1998b | 128.1 | 2635.6 | 23.7 | 176.6 | 13.7 | 1.7 | 75.9 | 16.3 | 386.6 | 110.4 | 71.5 | 62.9 |

| 1998–1999b | 122.6 | 2645.2 | 34.8 | 191.7 | 19.6 | 1.6 | 85.4 | 14.7 | 397.9 | 102.9 | 78.7 | 62.6 |

| 1999–2000b | 118.9 | 2749.1 | 23.4 | 189.8 | 15.1 | 1.6 | 78.9 | 15.4 | 396.8 | 107.1 | 73.9 | 64.5 |

| 2000–2001 | 147.3 | 2484.6 | 46.3 | 184.9 | 18.0 | 1.4 | 44.4 | 12.6 | 162.1 | 89.5 | 43.2 | 57.9 |

| 2001–2002b | 129.2 | 2459.6 | 38.5 | 186.1 | 16.6 | 1.2 | 74.5 | 12.1 | 383.6 | 88.9 | 73.6 | 57.4 |

| 2002–2003 | 163.2 | 2222.6 | 40.3 | 163.8 | 16.0 | 1.1 | 41.6 | 11.0 | 164.6 | 77.1 | 41.6 | 51.2 |

| 2003–2004b | 318.0 | 2141.2 | 91.5 | 174.1 | 21.2 | 1.2 | 92.2 | 10.4 | 508.5 | 71.0 | 100.3 | 49.9 |

| 2004–2005b | 140.0 | 1866.3 | 52.1 | 153.2 | 22.5 | 1.2 | 89.7 | 9.5 | 452.9 | 63.3 | 89.3 | 43.9 |

| 2005–2006b | 171.3 | 1937.7 | 41.1 | 152.0 | 15.1 | 1.2 | 57.3 | 9.6 | 291.9 | 62.3 | 59.4 | 44.7 |

| 2006–2007 | 163.7 | 1817.2 | 32.7 | 139.5 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 30.4 | 7.8 | 136.9 | 58.6 | 32.6 | 41.6 |

| 2007–2008b | 236.8 | 1915.4 | 64.6 | 163.7 | 25.0 | 1.4 | 81.4 | 7.3 | 380.9 | 53.7 | 82.7 | 43.8 |

| Minimum | 49.5 | 1817.2 | 14.7 | 139.5 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 30.4 | 7.3 | 136.9 | 53.7 | 32.6 | 41.6 |

| Maximum | 318.0 | 3150.7 | 91.5 | 260.4 | 25.0 | 2.6 | 92.2 | 19.9 | 508.5 | 124.5 | 100.3 | 77.4 |

| Mean | 151.0 | 2345.1 | 38.8 | 178.2 | 16.8 | 1.5 | 65.6 | 12.8 | 309.1 | 86.1 | 63.5 | 55.3 |

| 95% CI | 105.3–659.6 | 2219.3–2524.7 | 24.1–213.2 | 155.3–230.1 | 9.8–58.4 | 1.0–12.3 | 35.0–270.0 | 2.4–73.9 | 186.0–1103.7 | 37.3–326.2 | 37.5–236.6 | 44.4–106.7 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Data are hospitalization rates per 100 000 person-years and represent summaries from 13 state-based model estimates.

Standardized with 2000 census population figures for each age group.

Seasons in which ≥50% of all infection isolates were subtyped as influenza A(H3N2).

By influenza type/subtype, H1N1 hospitalization rates were the lowest (1.9/100000 person-years; 95% CI, .6–60.9) and H3N2 rates were the highest (44.4/100000 person-years; 95% CI, 29.3–98.1) (Table 4). If each virus was considered separately, RSV was associated with the highest hospitalization rates, followed by H3N2, B, and H1N1 viruses (Tables 3 and 4); this effect was due to the high rates of RSV infection in children aged <5 years. H3N2 viruses were associated with the highest hospitalization rates in persons aged ≥5 years. The hospitalization burdens of RSV, H1N1, and B viruses were similar among persons aged ≥65 years.

Table 4.

Estimated Influenza Type- or Subtype-Specific Hospitalization Rates by Negative Binomial Regression Models

| Aged <1 y | Aged 1–4 y | Aged 5–49 y | Aged 50–64 y | Aged ≥65 y | All Agesa | |||||||||||||

| Season | A(H1) | A(H3) | B | A(H1) | A(H3) | B | A(H1) | A(H3) | B | A(H1) | A(H3) | B | A(H1) | A(H3) | B | A(H1) | A(H3) | B |

| 1993–1994b | 0.8 | 91.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 14.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 55.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 234.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 47.3 | 0.2 |

| 1994–1995b | 8.1 | 34.1 | 7.4 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 32.4 | 17.3 | 0.2 | 145.0 | 57.8 | 0.3 | 27.1 | 15.0 |

| 1995–1996 | 135.8 | 48.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 10.1 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 26.5 | 11.9 | 6.5 | 124.2 | 36.0 | 6.0 | 23.7 | 10.3 |

| 1996–1997b | 0.0 | 66.9 | 26.5 | 0.0 | 6.1 | 32.3 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 12.1 | 0.0 | 52.0 | 32.3 | 0.0 | 258.0 | 111.8 | 0.0 | 46.8 | 28.8 |

| 1997–1998b | 1.5 | 126.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 23.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 13.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 75.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 384.4 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 70.9 | 0.6 |

| 1998–1999b | 1.2 | 96.4 | 25.0 | 0.1 | 8.7 | 26.0 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 59.0 | 26.3 | 0.0 | 307.9 | 90.0 | 0.0 | 55.0 | 23.7 |

| 1999–2000b | 16.6 | 102.3 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 20.5 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 14.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 77.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 391.9 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 72.2 | 1.2 |

| 2000–2001 | 126.3 | 1.2 | 19.8 | 7.1 | 0.1 | 39.1 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 15.4 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 40.1 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 149.0 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 37.0 |

| 2001–2002b | 8.2 | 112.0 | 10.7 | 0.4 | 12.4 | 26.3 | 0.1 | 9.5 | 7.1 | 0.1 | 57.3 | 17.9 | 0.6 | 317.7 | 69.9 | 0.3 | 56.6 | 17.6 |

| 2002–2003 | 132.0 | 15.5 | 16.4 | 10.6 | 2.2 | 28.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 11.0 | 3.1 | 11.9 | 26.9 | 6.3 | 65.5 | 94.0 | 5.7 | 11.6 | 24.7 |

| 2003–2004b | 0.0 | 318.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 89.4 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 20.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 91.2 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 503.7 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 99.0 | 1.2 |

| 2004–2005b | 0.0 | 108.2 | 31.8 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 43.4 | 0.0 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 0.0 | 56.9 | 32.8 | 0.0 | 319.6 | 133.2 | 0.0 | 56.5 | 32.7 |

| 2005–2006b | 10.7 | 151.2 | 14.1 | 0.3 | 13.1 | 28.8 | 0.2 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 42.5 | 16.6 | 0.7 | 237.0 | 64.5 | 0.3 | 44.1 | 16.9 |

| 2006–2007 | 124.6 | 33.1 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 5.0 | 17.6 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 16.8 | 11.6 | 5.7 | 91.4 | 42.0 | 4.8 | 16.7 | 11.5 |

| 2007–2008b | 156.7 | 50.9 | 29.2 | 10.1 | 5.8 | 48.7 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 16.2 | 1.5 | 39.1 | 40.9 | 3.2 | 212.2 | 165.5 | 4.9 | 37.5 | 40.4 |

| Minimum | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 |

| Maximum | 156.7 | 318.0 | 31.8 | 10.7 | 89.4 | 48.7 | 3.3 | 20.7 | 16.2 | 4.4 | 91.2 | 40.9 | 7.0 | 503.7 | 165.5 | 6.4 | 99.0 | 40.4 |

| Mean | 48.2 | 90.4 | 13.0 | 3.3 | 14.5 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 1.0 | 46.3 | 18.5 | 2.1 | 239.9 | 68.4 | 1.9 | 44.4 | 17.5 |

| 95% CI | 32.6–232.6 | 70.2–225.0 | 2.9–203.8 | 0.0–66.3 | 8.0– | 15.6–79.7 | 0.2–15.6 | 5.0–21.6 | 4.6–21.4 | 0.0–70.8 | 28.5–111.8 | 6.6–88.4 | 0.0–268.0 | 164.0–485.5 | 22.6–344.6 | 0.6–60.9 | 29.3–98.1 | 7.7–77.3 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Data are hospitalization rates per 100 000 person-years and represent summaries from 13 state-based model estimates.

Standardized with 2000 census population figures for each age group.

Seasons in which ≥50% of all infection isolates were subtyped as influenza A(H3N2).

Comparison of Influenza and RSV Hospitalization Estimates With ICD-9-CM–Coded Diagnoses

Among influenza-associated hospitalizations, a mean of 21% (range, 12%–29%) was specifically coded for influenza. Among RSV-associated hospitalizations, 59% (range, 49%–73%) were coded for RSV (Table 5). These proportions varied by age group; for example, 57% of estimated influenza hospitalizations in infants aged <1 year were coded for influenza versus 15% in those aged ≥65 years.

Table 5.

Proportions of Estimated Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Hospitalizations Listing an ICD-9-CM Code for Influenza or RSV

| Influenza | RSV | |||

| Age Group, y | Mean, % | Range | Mean, % | Range |

| <1 | 57.30 | 21.9–87.6 | 76.20 | 61.5–89.0 |

| 1–4 | 53.80 | 26.8–91.6 | 73.70 | 65.2–83.9 |

| 5–49 | 32.20 | 17.6–48.5 | 64.30 | 56.9–76.2 |

| 50–64 | 17.30 | 8.5–28.9 | 5.30 | 1.7–16.5 |

| ≥65 | 14.70 | 6.0–23.3 | 1.70 | 0.5–5.9 |

| All ages | 20.90 | 12.1–29.3 | 59.00 | 49.1–73.1 |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

DISCUSSION

We simultaneously estimated influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalizations by using inpatient hospital discharge data from 13 states representing approximately 40% of the US population. The use of complete hospitalization databases for 15 seasons allowed us to estimate hospitalizations by finer age groups than in previous national studies [11], including hospitalizations in children aged <1 year. Our results suggest that, although influenza and RSV have similar US hospitalization burdens, their age-specific burdens differ dramatically. Whereas RSV is associated with 16 times more hospitalizations than influenza in children aged <1 year, influenza causes 8 times more hospitalizations than RSV in people aged >5 years. We found that approximately 20% of influenza hospitalizations had an influenza-specific discharge diagnosis, whereas the proportion was 59% for RSV. Influenza and RSV diagnoses were less frequently found in older adults, who are less frequently tested for respiratory virus infections than young children.

Because testing for infections possibly associated with wintertime respiratory and circulatory hospitalizations is not routine, several statistical models have been used to estimate influenza- and RSV-associated morbidity. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses [7, 9–13]. Our model summed hospitalizations specifically coded for either influenza or RSV with estimates of additional hospitalizations associated with each of these pathogens. These estimates were made by using a refinement of statistical models described elsewhere [7, 11–13] with respiratory and circulatory hospitalizations not coded for influenza or RSV. Potential problems with this approach include the possibility that influenza or RSV coding practices changed during the study period and that some influenza- or RSV-coded hospitalizations may not have been tested for these viruses. However, we think this modeling approach is more logical than previous approaches, which have applied statistical models to hospitalizations already coded as due to influenza or RSV.

Influenza-associated hospitalizations varied substantially by season during the study period, related to the particular influenza virus types and subtypes in circulation [7, 9, 12]. We found a 3-fold variation in the annual rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations during our 15-year study period, whereas RSV-associated hospitalization rates were relatively stable. As expected, H3N2 viruses were associated with the highest hospitalization rates. The mean rate of influenza-associated hospitalizations was twice as high during seasons dominated by H3N2 viruses than during seasons dominated by B and H1N1 viruses. These results are consistent with previous findings obtained with 1969–1995 National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) data using a different statistical model [24].

Similar to previous influenza studies, persons aged ≥65 years had the highest influenza-associated hospitalization rates, followed by infants. Among adults aged ≥65 years, we estimated an annual mean of 309 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100000 person-years. This estimate is lower than a previous national estimate made using NHDS data of 461 per 100000 person-years [11]. The difference may be explained by the study period used, the data source (complete 13-state data vs a sample of hospitalizations in the entire United States), the spatial resolution, variation in the use of viral surveillance data, the inclusion of an RSV term in this model, and the statistical model used (negative binominal vs Poisson). An advantage of negative binomial regression models is that they are appropriate for overdispersed data, and our hospitalization data were overdispersed. Among infants aged <1 year, an annual mean of 151 hospitalizations per 100000 person-years occurred, whereas the corresponding estimate among children aged 1–4 years was 39 hospitalizations per 100000 person-years. The estimated rate among children aged <5 years was 94 (not shown in a table), which is similar to an estimate of 108 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100000 person-years made with NHDS hospitalization data during 1979–2001 [11]. Our estimate is very similar to results from another study that found a reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)–confirmed influenza hospitalization rate of 90 per 100000 person-years among children aged <5 years in 3 US counties during the 2000–2001 through 2003–2004 seasons [6].

Rates of RSV-associated hospitalizations were highest among infants and young children, followed by the elderly. Our estimates for RSV-associated hospitalizations among infants and young children are similar to estimates from previous studies. For example, Holman et al [17] estimated 2700 RSV-associated hospitalizations occurred per 100000 person-years among children aged <1 year by using 2000–2001 NHDS hospitalizations, comparable with our estimated rate of 2300 among infants. Our estimate of 384 RSV-associated hospitalizations per 100000 children aged <5 years is similar to a rate of 290 obtained in a prospective study of laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations conducted from 2000–2001 through 2003–2004 [4].

Our results and those of Mullooly et al [8] suggest that the annual hospitalization burden of influenza in older adults is substantially greater than that of RSV. In contrast, a hospital cohort study performed by Falsey et al [2] showed no significant difference in the proportion of hospitalized elderly patients who tested positive for influenza or RSV—12% and 10%, respectively. The study by Falsey et al was small (1388 hospitalized elderly patients) and restricted to individuals with underlying cardiopulmonary disease, and influenza vaccination rates were high.

Validation of influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalization rates derived from statistical models is vital if modeling estimates are to be accepted and applied by researchers and policy makers worldwide. Validation also represents a great challenge, as there are few gold-standard data that can be used for comparison. Ideally, reference-standard results would be derived from prospective studies enrolling and testing hospitalized patients with a sensitive and specific laboratory test, such as RT-PCR. However, PCR-confirmed influenza and RSV hospitalization data are scarce, particularly over the full spectrum of age, from infants through the elderly.

Gilca et al [25] compared estimates obtained from several statistical methods of influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalization with observations from a prospective study with virus detection in children who were hospitalized for acute respiratory illness. In this Canadian study, no single statistical method consistently reflected prospective estimates. However, negative binomial regression, which we used, generated the RSV hospitalization estimates most closely matched to prospective results.

One recent US study provides data that we can use to make independent comparisons with some of our results. Dawood et al [1] studied seasonal influenza hospitalizations among children in the 10 Emerging Infections Program (EIP) sites and found hospitalization rates among children aged <1 year and 1–4 years were 113 and 29 per 100000 children, respectively (see Supplemental Table 1). Our estimates for the same period are 201 and 54 per 100000 person-years for children aged <1 year and 1–4 years, respectively. The EIP rates are underestimates because influenza testing was performed as ordered by clinicians rather than according to a protocol, and most cases were identified by rapid influenza tests, which have low sensitivity [26]. Grijalva et al [27, 28] performed a capture-recapture evaluation of EIP surveillance in children aged <5 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza and concluded that the sensitivity of the EIP system for detecting influenza in hospitalized patients was 39%. If we adjust the estimates of Dawood et al for sensitivity, the adjusted rates fall within the CIs of our estimates (Supplemental Table 1). Overall, we conclude that our population-level influenza hospitalization estimates in children are comparable to the EIP data.

This study has several limitations. First, patient age was not available in influenza and RSV surveillance data. There may be temporal differences the incidence of influenza and RSV by age group, although available data suggest that for influenza these differences are measured in days rather than weeks [29]. Second, because the onset, duration, and intensity of virus circulation typically vary by geography [30], aggregating virus surveillance data by the 4 census regions may not adequately capture state-level viral circulation patterns. However, our model requires consistent and robust weekly viral surveillance data for estimating the effects of influenza and RSV circulation. [12, 31], and such data are not yet available at the state level. Third, the frequency of specimen collection and the testing practice vary throughout the seasons and thus could influence our estimates. Fourth, other respiratory viruses often cocirculate with RSV and influenza, including human metapneumovirus and the human parainfluenza viruses, and these viruses could confound the relationships described in this study, although they typically are not the most common respiratory pathogens in any age group. Few data are available on the age-specific circulation patterns of most respiratory viruses, including RSV. Finally, as noted above, our estimates need additional validation, and recent work from Hong Kong suggests that the general regression approach we used can produce satisfactory estimates of influenza hospitalizations among persons aged <18 years, based on prospective virus testing in a similar population [32].

We used robust data for a substantial proportion of the US population to estimate influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalizations and to evaluate age, geographical, and temporal trends in these hospitalizations. A similar approach could be applied in other countries, including those in Europe and Asia that collect weekly hospitalization data. Our age-specific estimates for seasonal influenza-associated hospitalizations provide a key baseline against which to assess the age-specific impact of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and monitor trends in the effectiveness of influenza control policies during pandemic and interpandemic periods. Estimates of infectious disease burden from modeling studies should be further validated with results from large studies prospectively testing hospitalized patients with PCR assays.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Fatimah Dawood and the site investigators for providing the Emerging Infections Program data on hospitalization for influenza.

Disclaimer.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support.

This work was supported by internal funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Potential conflicts of interest.

Dr. Anderson has received consulting fees from Medimmune and Novartis Vaccines, grants from Trellis Bioscience, and travel expenses from Medimmune. All other authors have no conflicts to report.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Dawood FS, Fiore A, Kamimoto L, et al. Influenza-associated pneumonia in children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza, 2003–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:585–90. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e3181d411c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1749–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fry AM, Chittaganpitch M, Baggett HC, et al. The burden of hospitalized lower respiratory tract infection due to respiratory syncytial virus in rural Thailand. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwane MK, Edwards KM, Szilagyi PG, et al. Population-based surveillance for hospitalizations associated with respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza viruses among young children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1758–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:31–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson MG, Shay DK, Zhou H, et al. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullooly JP, Bridges CB, Thompson WW, et al. Influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalizations among adults. Vaccine. 2007;25:846–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Williamson GD, Stroup DF, Arden NH, Schonberger LB. The impact of influenza epidemics on mortality: introducing a severity index. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1944–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, Blackwelder WC, Taylor RJ, Miller MA. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:265–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson WW, Weintraub E, Dhankhar P, et al. Estimates of US influenza-associated deaths made using four different methods. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2009;3:37–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin MR, Coffey CS, Neuzil KM, Mitchel EF, Jr, Wright PF, Edwards KM. Winter viruses: influenza- and respiratory syncytial virus-related morbidity in chronic lung disease. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1229–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izurieta HS, Thompson WW, Kramarz P, et al. Influenza and the rates of hospitalization for respiratory disease among infants and young children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:232–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holman RC, Curns AT, Cheek JE, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among American Indian and Alaska Native infants and the general United States infant population. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e437–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Introduction to the HCUP state inpatient databases. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/siddist/Introduction_to_SID.pdf. Accessed 25 December 2010.

- 19.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay DK, et al. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Bureau of the Census. State single year of age and sex population estimates. 2009. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/estimates.html. Accessed 12 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brammer L, Budd A, Cox N. Seasonal and pandemic influenza surveillance considerations for constructing multicomponent systems. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2009;3:51–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus activity—United States, July 2007–December 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1355–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonsen L, Fukuda K, Schonberger LB, Cox NJ. The impact of influenza epidemics on hospitalizations. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:831–7. doi: 10.1086/315320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilca R, De Serres G, Skowronski D, Boivin G, Buckeridge DL. The need for validation of statistical methods for estimating respiratory virus–attributable hospitalization. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:925–36. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid diagnostic testing for influenza. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/rapidlab.htm. Accessed 9 November 2010.

- 27.Grijalva CG, Craig AS, Dupont WD, et al. Estimating influenza hospitalizations among children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:103–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grijalva CG, Weinberg GA, Bennett NM, et al. Estimating the undetected burden of influenza hospitalizations in children. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:951–8. doi: 10.1017/S095026880600762X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schanzer D, Vachon J, Pelletier L. Age-specific differences in influenza A epidemic curves: do children drive the spread of influenza epidemics? Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:109–17. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity—United States, September 30–December 1, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viboud C, Alonso WJ, Simonsen L. Influenza in tropical regions. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Chiu SS, Chan KP, et al. Validation of statistical models for estimating hospitalization associated with influenza and other respiratory viruses. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.