Abstract

Clinical and laboratory investigations have provided evidence that ethanol suppresses normal lung immunity. Our initial studies revealed that acute ethanol exposure results in transient suppression of phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by macrophages as early as 3 hours after initial exposure. Focusing on mechanisms by which ethanol decreases macrophage Fcγ-receptor (FcγR) phagocytosis we targeted the study on the focal adhesion and cytoskeletal elements that are necessary for phagosome progression. Ethanol inhibited macrophage phagocytosis of IgG-coated bead recruitment of actin to the site of the phagosome, dampened the phosphorylation of vinculin, but had no effect on paxillin phosphorylation suggesting a loss in “phagosomal adhesion” maturation. Moreover, our observations revealed that FcγR-phagocytosis induced Rac activation, which was increased by only 50% in ethanol exposed cells, compared to 175% in the absence of ethanol. This work is the first to show evidence of the cellular mechanisms involved in the ethanol-induced suppression of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis.

Keywords: alcohol, phagosome, small GTPase, Rac, Rho, VavGEF, alveolar macrophage, RAW264.7

Introduction

The consumption of alcohol (ethanol) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, contributing to 3.8% of all death and 4.6% of disease globally [1–3]. Clinical observations and laboratory studies have linked acute ethanol exposure with suppressed immune function, specifically, decreased leukocyte activation in response to a pathogen or a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) in many organs, including the lungs [4–8]. Previous work has provided evidence that acute exposure to ethanol can reduce monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis [9–14]. Specifically, Morland's group reported that acute ethanol exposure inhibited phagocytosis via the Fcγ-receptor (FcγR) [10]. Others have focused on the mechanisms involved in ethanol attenuation of cytokine production after ligand binding to Toll-like receptors (TLR) [4, 15]. Decreased mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) dysregulation, and insufficient receptor clustering in lipid rafts have all been shown to contribute to this ethanol-mediated immunosuppression [4, 9, 15–17]. However, only limited progress has been made in understanding the underlying mechanisms involved in ethanol-mediated suppression of phagocytosis.

Phagocytosis can be initiated by binding of a PAMP with a phagocytic receptor or by opsonization of a pathogen by host molecules such as immunoglobulin G (IgG) or complement [18]. In parallel, pathogens can also activate numerous pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including the Toll-like receptors, mannose receptors, and scavenger receptors, alerting the host to an inflammatory threat. Together, these immediate immune-mediate responses alert the host to an inflammatory threat, enhancing recognition and phagocytosis of the invading pathogen. The two most commonly studied modes of phagocytosis are via the FcγR and the complement receptor. Initiation of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis requires the binding of the receptor to the Fc portion of IgG. This interaction induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the gamma subunit of the receptor and subsequent downstream activation of the phagocytic pathway [19–20]. As with most types of phagocytosis, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis requires involvement of the focal adhesion molecules paxillin and vinculin, as well as the actin cytoskeleton [21–22]. In the context of phagocytosis, paxillin and vinculin are thought to link the extracellular pathogen bound to receptors with the cellular cytoskeleton. Once anchored to the pathogen, the “phagosomal adhesion” can induce pathogen/particle internalization through its interaction with actinomyosin contractions as well as many other molecules [23–24]. The inability to induce an adhesion or loss of cytoskeletal control, i.e. normal actin architecture, is known to inhibit phagocytosis [25–26]. Interestingly, ethanol has been shown to modulate paxillin, vinculin, and actin in non-professional phagocytes, such as astrocytes [27–28]. This study demonstrates that ethanol exposure decreases phosphorylation of these critical adhesion molecules and alters actin recruitement, implicating a potential role for ethanol mediated dysregulation of these molecules in phagosomal maturation.

Downstream of the FcR, small GTPases are integral to the activation of these focal adhesion molecules, and subsequent actin recruitment to the phagosome. Though there are conflicting data regarding the relationship between specific small GTPases and the type of receptor mediated phagocytosis, Rac and Cdc42 are typically considered the signaling molecules downstream of the FcRs, whereas Rho is generally associated with complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis [29–32]. In support of this, in RAW264.7 and J774.A1 macrophages, tumorigenic cell lines isolated from murine ascites, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is inhibited following expression of the dominant negative Rac1 or Cdc42 plasmid Rac1N17 or Cdc42 N17, respectively [29–30]. This effect was also observed using IgE-opsonized particles and measuring RBL-2H3 mast cell phagocytosis after inhibition of Rac or Cdc42 [33]. Reports have also revealed that clustering of constitutively active Cdc42 or Rac1 leads to actin rearrangement, membrane ruffling, and particle engulfment [34–35], further highlighting the need for small GTPase activity in normal phagosomal development.

We sought to decipher the mechanisms involved in the ethanol-induced suppression of macrophage phagocytosis, specifically FcγR mediated phagocytosis. Initial work by our laboratory revealed that acute ethanol exposure suppressed bacterial phagocytosis [13]. In the present work, we broadened our understanding of the time dependent effects of ethanol on the phagocytosis of Pseudomonas (P.) aeruginosa. Additionally, we established that our in vitro ethanol experiments parallel our in vivo acute ethanol model, as demonstrated by decreased bacterial phagocytosis and diminished actin polymerization at the phagosome during IgG-induced FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. This suppression of actin polymerization was accompanied by reduced vinculin, but not paxillin, phosphorylation. Moreover, we expanded upon the differential role of two small GTPases, Rho and Rac, in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, and revealed that ethanol primarily impairs Rac activation in the context of macrophage phagocytosis. Our study extends the current understanding of the suppressive effects of acute ethanol exposure during macrophage phagocytosis, and attributes the aforementioned observations to ethanol-induced decreases in Rac activity during FcγR-mediate phagocytosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals, In Vivo Ethanol Exposure, and Alveolar Macrophage Isolation

Eight to 10 week old male C57BL/6 mice (Harlan, IN) were utilized to measure in vivo ethanol effects on alveolar macrophages. Prior to use, mice were acclimated for one week at the animal facility in Loyola University Medical Center. All animal studies described here were approved and performed with strict accordance to the rules and regulations set by the Loyola University Chicago Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were subjected to a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 2.2 g/kg ethanol or saline control as previously described [4, 13, 15]. This dose of ethanol resulted in a transient elevation in blood alcohol concentration (BAC) which peaked at a level of 280 mg/dl at 30 minutes and returned to baseline levels by 3 hours [13]. Following sacrifice, by CO2 exposure and cervical dislocation, alveolar macrophages were harvested by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at 0.5, 3, or 24 hours after ethanol administration. Briefly, 8 sequential 800 μL saline lavages were performed per animal as previously described [13]. Roughly 600 μL of collected BAL fluid and cell suspension were isolated per lavage resulting in a total of ~5 mL of BAL fluid. In either ethanol or saline exposed mice, cellular characterization by flow cytometry revealed 85–95% of our BAL cells were alveolar macrophages as determined by F4/80+ staining allowing studies to be performed on a purified primary macrophage without the use of receptor-mediated isolation (data not shown). Additionally, alveolar macrophages were utilized due to their frequent exposure to pathogens and their potential link to the increase in lung infection observed in people who abuse alcohol.

Cell Culture and In Vitro Ethanol Exposure

RAW264.7 cells, an immortalized macrophage cell line, were seeded (2.5 × 105) and incubated in 5% CO2 in either 6 well culture plates or p35 MatTek glass bottom dishes for 48 hours in complete media (RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (PSG)) (Invitrogen; Eugene, OR). Cells were then cultured in complete media with or without 50 mM (~0.3%) ethanol for 0.5, 1, 1.5, 3, 6, or 24 hours. Measurement of the ethanol concentration at these time points resulted in concentrations of 208.5, 217.5, 191, 179, 148, and 48 mg/dl, respectively. The RAW264.7 cell line was used as a model of primary culture macrophages due to the large number of cells needed for the molecular studies. This cell line has been used extensively in other studies examining the effects of alcohol on macrophage function [36]. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no published evidence suggesting the mechanisms involved in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis vary between different macrophage populations.

Phagocytosis and Bead Opsonization

Alveolar or RAW264.7 macrophages were cultured in media without antibiotics with 150 EGFP-P. aeruginosa per cell for 30 minutes in a 37°C incubator under constant rotation or adhered to a plastic dish, respectively. The number of bacteria per cell were chosen after performing dose response analyses in which 5–600 bacteria per cell were tested and the midpoint of the linear range of fluorescence intensity per cell following phagocytosis was selected (data not shown). At specified times, phagocytosis was ceased using ice cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), washed two additional times with PBS, and cultured with 5 μg/mL lysozyme for 30 minutes to eliminate any extracellular bacteria. RAW264.7 or alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa was then measured by flow cytometry (described below). The clearance of extracellular bacteria following lysozyme treatment was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy. FcγR-mediated phagocytosis consisted of opsonizing latex beads prior to phagocytosis. Three μm latex beads (Sigma LB30-1ML) were incubated in 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Beads were centrifuged and washed three times with PBS, then resuspended in 1 mL PBS. Ten μL mouse anti-BSA (Fisher MS-572-P1ABX) was added to the bead suspension and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour under constant rotation. This resulted in >99% coating of the beads (data not shown). Beads were subsequently washed two times with PBS, once with RPMI, and finally resuspended in RPMI which was added to the distributing media. Warm RPMI medium with beads at a concentration of 20 (or 50 for western blot studies) beads per cell were added to each well. Wells were briefly centrifuged and immediately placed into a 37°C incubator for specified times allowing phagocytosis to occur. Immediately following phagocytosis, cells were placed on ice and ice-cold PBS was added to the dish to stop phagocytosis. Cells were then either washed twice with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldahyde for immunocytochemistry or lysed for molecular studies.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed in the FACS lab (FACS Aria) at Loyola University Medical Center as described previously [37]. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells were incubated with RPMI including 10% FBS and 1% PSG with or without 50 mM ethanol for 3 hours after which they were detached from the plate with a cell scraper and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Because of the high affinity of FcγRI (CD64) to monomeric IgG, blocking of FcγRII (CD32) and FcγRIII (CD16) was not performed when staining for CD64 (APC-anti-CD64, R&D Systems, Minnesota). When staining for FcγRII (PE-anti-CD32, R&D Systems, Minnesota), blocking of FcγRI and III was performed using an antibody against FcγRIII. This allowed the blocking of FcγRIII by the specific antibody, and indirect blocking of FcγRI due to its high affinity to monomeric antibody. Similarly, when staining for FcγRIII (PE-anti-CD16, R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN), blocking of FcγRI and II was performed using an antibody against FcγRII. Fluorescence minus one control staining was performed to indicate positive staining and date analysis performed using FlowJo Software (Tree Star Inc; Ashland, OR).

Immunocytochemistry

Following addition of IgG coated beads, cultures of RAW264.7 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldahyde for 15 minutes. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X in PBS for 3 minutes, blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes, and stained with rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen; Eugene, OR) in 2% BSA for 30 minutes and Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen; Eugene, OR) in 2% BSA for 2 minutes following manufacturers specifications. Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope (Zeiss, Germany). For measurement of actin ring assembly at the phagosome, cells were stained for actin with rhodamine phalloidin. DIC images revealing the number of internalized beads were over-layed to corresponding fluorescent images. In brief, a ratio of activated phagosomes (ringed beads) to total internalized beads was then assessed under each condition. In order to get the clearest visualization of the phagosome, the focal plane of the fluorescent images were taken on the apical surface, or the site of initial contact between beads and cell, rather than the midsection of the cells, which would suggest a later stage of phagocytosis. Finally, this method does not distinguish between partially and completely internalized particles (though differences in bead shading in the DIC images may suggest depth of the bead).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot

Following exposure to ethanol and/or IgG-coated beads, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated using the protocol provided with the EZ-Detect Rac1 Activation Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and described by others [38]. Briefly, 1 × 106 RAW264.7 cells were cultured with or without ethanol as described above and stimulated with IgG-coated beads for various times. Cells were lysed in 100 μL Lysis/Binding/Wash buffer (Pierce), activated Rac1 was precipitated with glutathione S-transferase (GST-human Pak1-PBD), and detected with mouse anti-Rac1 by western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as previously described [4]. Briefly, cell extracts (20 mg protein per well) were electrophoretically separated on Ready Gels Tris-HCL, 4–20% (BioRad; Hercules, CA). Proteins were electroblotted onto immobilon-P blotting membrane, blocked in 3% nonfat milk in 0.5% tween PBS for 30 minutes and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibody in 3% nonfat milk. Primary antibodies against paxillin (Clone 5H11, Millipore, MA, USA), vinculin (Clone hVIN-1, Sigma, MO, USA), phosphorylated paxillin (Tyr118, Millipore, MA, USA), or phosphorylated vinculin (pTyr822, Sigma, MO, USA) were used at the manufacturers recommended dilutions. Secondary antibodies included goat-anti-rabbit (Abcam, MA, USA) or rabbit-anti-mouse (Abcam, MA, USA) antibodies at 1:5000 dilution for 1 hour in 3% nonfat milk diluted in 0.5% tween PBS. Membranes were developed with SuperSignal West Dura Luminol/Enhancer solution and Peroxide Buffer (ThermoScientific, MA, USA) and evaluated via densitometric analysis using the BioRad Chemi Dock XRS. Histograms shown are the average of 3 or 4 experiments, and blots are shown for one representative experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of each group. Data were analyzed by t test, or ANOVA, followed by post hoc Dunnetts Multiple Comparison test using Instat 3 (Graphpad; La Jolla, CA) using vehicle or 0 minutes time point as control. A value of p≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Macrophage phagocytosis of EGFP-P. aeruginosa was suppressed after acute ethanol exposure

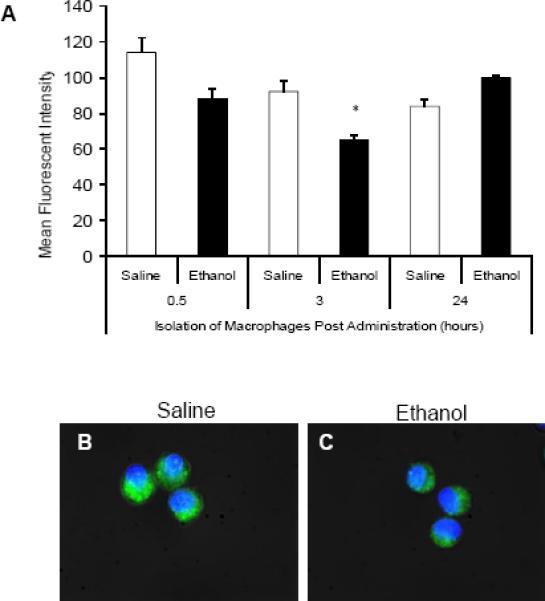

To examine mechanisms by which ethanol suppresses phagocytosis, we first assessed whether acute ethanol exposure affects the ability of macrophages to phagocytose EGFP-P. aeruginosa. Alveolar macrophages were obtained from the lungs of male C57BL/6 mice by BAL at 0.5, 3, or 24 hours after a single exposure to 2.2g/kg of ethanol. Phagocytosis was measured by ex vivo culture with EGFP-P. aeruginosa. Fluorescent intensity was used as an index of phagocytosis of EGFP-P. aeruginosa. Three hours after ethanol exposure, macrophages demonstrated a 30% (p<0.05) decrease in mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) when compared to macrophages isolated from saline treated controls (Figure 1A). This was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy at 3 hours after saline (Figure 1B) or ethanol (Figure 1C) where macrophages from the latter group had a reduction in the fluorescence. MFI was calculated as the result of an unchallenged cell subtracted from a cell challenged with bacteria. To parallel our in vivo model, we cultured the RAW264.7 macrophage cell line with 50 mM ethanol for various times from 0.5 to 24 hours followed by a 30 minute incubation with EGFP-P. aeruginosa. Mean fluorescent intensity measured by flow cytometry indicated that ethanol transiently induced suppression in macrophage phagocytosis at the 3 hour time point which is restored following 6 hours of ethanol treatment (Figure 2). Finally, in vitro ethanol exposure for 1.5 hours showed a slight but insignificant increase in phagocytosis by the RAW264.7 cells that was not observed in subsequent experiments. Together, these data provide in vivo and in vitro evidence supporting ethanol impaired macrophage phagocytosis of foreign pathogens.

Figure 1.

In vivo ethanol suppresses ex vivo alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of EGFP-P.aeruginosa. A: Mean fluorescent intensity of alveolar macrophages isolated 0.5, 3, or 24 hours after in vivo saline (open bars) or ethanol (closed bars) exposure. Macrophages were cultured with 150 bacteria per cell for 30 minutes and analyzed by flow cytometry. B and C: Fluorescent microscopy of alveolar macrophages isolated 3 hours after mice were exposed to i.p. saline (B) or ethanol (C) and allowed to phagocytose fluorescent bacteria. *, p<0.05 compared to saline 3 hours. n=3 animals per group. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Green-EGFP-P. aeruginosa, Blue-Nuclear Hoechst stain

Figure 2.

In vitro ethanol reduces RAW264.7 macrophage phagocytosis of EGFP-P. aeruginosa. RAW264.7 macrophages were cultured with either control media (open bar) or media containing 50 mM ethanol for 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, or 24 hours (closed bars). Subsequently, cells were co-cultured with 150 EGFP-P. aeruginosa for 30 minutes and the fluorescent intensity of cells was determined via flow cytometry. *, p<0.05 compared to saline 3 hours. n=3 wells per group. Green-EGFP-P. aeruginosa Blue-Nuclear Hoechst stain

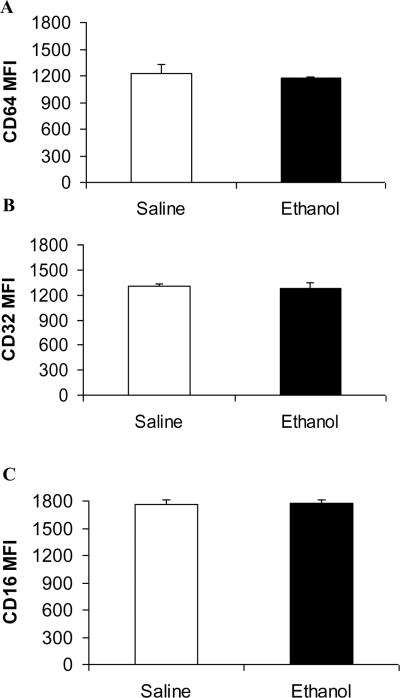

Acute ethanol exposure did not alter Fcγ-receptor expression

To determine whether ethanol mediated suppression of phagocytosis involves changes in receptor expression, alveolar macrophages were isolated 3 hours after initial in vivo administration of saline or ethanol. Surface expression of FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), and FcγRIII (CD16) was examined by flow cytometry using fluorescent conjugated antibodies (Figure 3). Our data reveal that acute ethanol exposure did not alter surface expression of the three FcγRs on alveolar macrophages. These data are consistent with our in vitro studies, which also showed acute ethanol exposure did not modulate RAW264.7 cells FcgR levels (data not shown). This suggests that defects downstream of the receptor may play a role in reduced macrophage phagocytosis after ethanol exposure.

Figure 3.

Surface FcγR expression is not altered after acute ethanol exposure. Alveolar macrophages isolated from mice receiving either saline (open bars) or ethanol (closed bars) for 3 hours were stained with anti-FcγRI (CD64) (A), FcγRII (CD32) (B), or FcγRIII (CD 16) (C). Receptor expression levels are expressed as relative mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

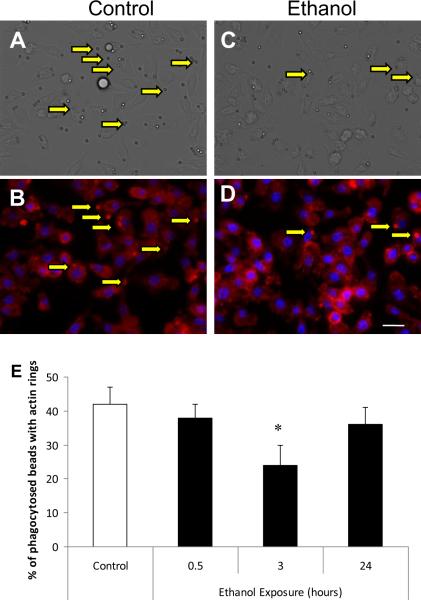

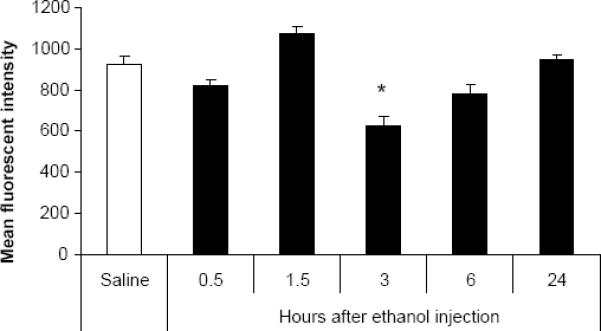

Actin polymerization was reduced at the site of the phagosome in macrophages exposed to acute ethanol

In order to understand how acute ethanol exposure suppresses FcγR mediated phagocytosis, we measured the ability of ethanol exposed alveolar and RAW264.7 macrophages to induce actin polymerization to the phagosome, a mechanism required for phagocytosis [39–40]. Alveolar macrophages were isolated 0.5, 3, or 24 hours after in vivo saline or ethanol exposure and assessed for actin polymerization to the site of the phagosome during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of alveolar macrophages after internalization of IgG coated beads were used to determine the number of beads phagocytosed (Figures 4A and C). This value did not differ between control and ethanol treated cells (60% vs. 64%, respectively). Fluorescent images, stained with rhodamine phalloidin (red) and Hoechst nuclear stain (blue), of the same cells were taken to measure the number of actin rings (arrows) formed at 20 minutes after beads were added to the cells (Figures 4B and D). The number of internalized beads inducing actin polymerization (Figure 4E) and the number of actin rings per cell (data not shown) were decreased by 40% (p<0.05) in the cells that were isolated from mice 3 hours after ethanol exposure. It is important to note that in order to get the most clear visualization of the phagosome, the focal plane of the fluorescent images are on the apical surface, rather than the midsection of the cells. Additionally, these data do not distinguish between partially and completely internalized particles (though differences in bead shading may suggest depth of the bead). More importantly, they reveal the ability of the FcRs to become activated and induce localized actin remodeling. These observations are the first to provide evidence that acute ethanol exposure suppresses actin polymerization at the site of a phagosome, through suppression of the FcγR pathway.

Figure 4.

FcγR-mediated actin polymerization is decreased after ethanol exposure. Alveolar macrophages were isolated from mice 3 hours after receiving i.p. saline (A and B) or ethanol (C and D). Cells were plated and allowed to phagocytose IgG coated beads for 20 minutes. A and C: Differential image contrast (DIC) microscopy of alveolar macrophages was performed to indicate internal versus external beads. B and D: Fluorescent microscopy of alveolar macrophages stained with rhodamine phalloidin (red) shows actin polymerization at the phagosome, and nuclear Hoechst stain (blue). E: Percent of internalized beads that induce actin polymerization during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. Alveolar macrophages collected from saline exposed mice versus 0.5, 3, or 24 hours of ethanol exposure. *, p<0.05 compared to saline. n= 50–75 cells per group. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar= 20 μm

In parallel, at 3 hours of culture of RAW264.7 cells with ethanol, actin polymerization around the phagosome was suppressed. Figures 5A and C show DIC images of RAW264.7 cells with internalized IgG coated beads with or without prior ethanol exposure. Corresponding images representing actin polymerization and nuclear staining are shown using fluorescent microscopy (Figures 5B and D). The percent of internalized beads that recruited actin to the phagosome (arrows) was decreased by 45% (p<0.05) at 3 hours of ethanol exposure relative to control (Figure 5E). Interstingly, the reduction in actin association with the phagosome was not observed after 0.5 or 24 hours of ethanol exposure. The observed changes were not a result of differences in binding of beads to cells after ethanol treatment for either alveolar macrophages or RAW264.7 cells (data not shown). The data observed in Figure 5 parallel the ethanol-induced suppression of actin polymerization observed in vivo, and led us to further examine the role of phagosomal adhesion maturation and the underlying mechanisms involved in ethanol induced suppression of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis.

Figure 5.

Actin polymerization to the FcγR-mediated phagosome is suppressed after ethanol exposure in RAW264.7 macrophages. RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to control media (A and B) or media containing 50 mM ethanol (C and D) for three hours were plated and allowed to phagocytose IgG coated beads for 20 minutes. A and C: Differential image contrast (DIC) microscopy of RAW264.7 cells after 20 minutes of IgG bead phagocytosis indicate internal versus external beads. B and D: Fluorescent microscopy of RAW264.7 cells stained with rhodamine phalloidin to reveal actin polymerization at the phagosome, and nuclear Hoechst stain. E: RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to control media versus 0.5, 3, or 24 hours of 50 mM ethanol media. *, p<0.05 compared to saline. n= 75–125 cells per group. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar= 18 μm

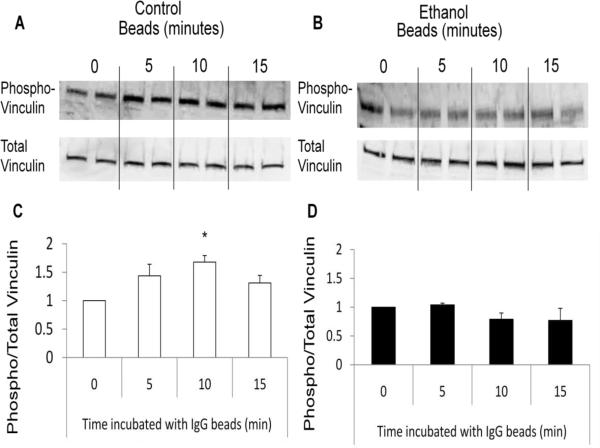

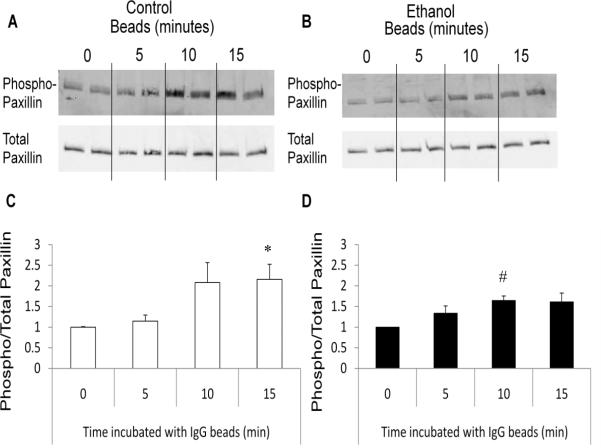

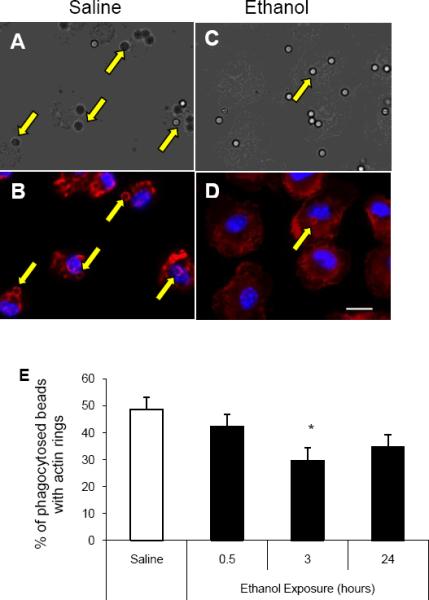

Vinculin but not paxillin phosphorylation was suppressed by ethanol during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis

To determine if ethanol altered vinculin and paxillin phosphorylation during phagocytosis, we cultured RAW264.7 cells with or without 50 mM ethanol for 3 hours after which the cells were incubated with IgG coated beads for 0, 5, 10, or 15 minutes. Our data revealed that cells cultured in the absence of ethanol had a 70% (p<0.05) increase in vinculin phosphorylation following 10 minutes of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis (Figure 6A and C). This rise in vinculin phosphorylation was not observed in cells previously exposed to ethanol for 3 hours, but rather levels of vinculin phosphorylation did not alter during phagocytosis compared to cells that were not exposed to IgG-coated beads (Figure 6B and D). Without ethanol, RAW264.7 cells also exhibited a 2-fold (p<0.05) increase in paxillin phosphorylation at 15 minutes (and nearly significant at 10 minutes) after the addition of beads (Figure 7A and C). However, in contrast to the reduction in vinculin phosphorylation seen in ethanol-exposed cells, ethanol-exposure did not inhibit phosphorylation of paxillin in response to IgG-coated beads (Figure 7B and D). Further studies revealed that the reduced vinculin phosphorylation observed in the ethanol-exposed cells was not a delayed response to the FcγR stimulus as vinculin suppression in ethanol-exposed cells was maintained up to 60 minutes after IgG bead stimulation (data not shown). These data suggest one mechanism by which ethanol suppresses FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is by inhibiting phagosomal adhesion maturation.

Figure 6.

Phosphorylation of vinculin is suppressed during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis after acute ethanol exposure. RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to control media (open bars) or media containing 50 mM ethanol (closed bars) for 3 hours were co-cultured with IgG coated beads to initiate FcγR-mediated phagocytosis for 0, 5, 10, or 15 minutes. Cells were subsequently lysed and total and phosphorylated protein levels for vinculin (A and B) were quantified by western blot analysis. Total and phosphorylated vinculin was quantified after 0, 5, 10, and 15 minutes of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in control (C) and ethanol (D) exposed RAW264.7 cells. *p<0.05 compared to 0 minutes. Data are the average of three independent experiments, each column represents an individual sample.

Figure 7.

Phosphorylation of paxillin is not suppressed during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis after acute ethanol exposure. RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to control media (open bars) or media containing 50 mM ethanol (closed bars) for three hours were co-cultured with IgG coated beads to initiate FcγR-mediated phagocytosis for 0, 5, 10, or 15 minutes. Cells were subsequently lysed and total and phosphorylated protein levels for paxillin (A and B) were quantified by western blot analysis. Total and phosphorylated paxillin was quantified after 0, 5, 10, and 15 minutes of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in control (C) and ethanol (D) exposed RAW264.7 cells. *p<0.05 compared to 0 and 5 minutes, # p<0.05 compared to 0 minutes. Data are the average of three independent experiments, each column represents an individual sample.

Differential importance of Rac and Rho during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis

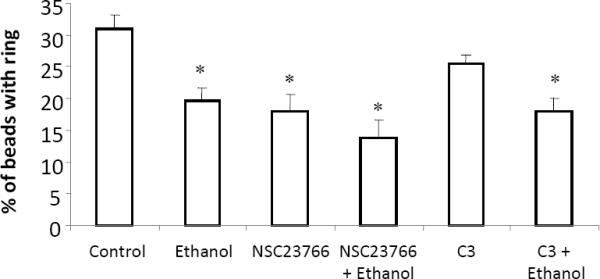

After demonstrating that ethanol suppressed phagosomal actin polymerization and differentially regulated the focal adhesion molecules vinculin and paxillin, we sought to better understand the importance of the small GTPases Rac and Rho in our model of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. To achieve this, RAW264.7 cells were cultured with either a Rho inhibitor (C3), a Rac inhibitor (NSC23766), or a combination of one of these inhibitors plus ethanol prior to the addition of IgG coated beads to our culture. For these studies, the ability of these cells to induce actin polymerization to the site of the phagosome was measured. Consistent with our previous findings, there was a ~40% (p<0.05) ethanol mediated reduction in actin polymerization following FcγR activation compared to cells that were not exposed to ethanol (Figure 8). Inhibition of Rac with NSC23766 resulted in a 45% decrease (p<0.05) in phagosome F-actin recruitment, and the combination of NSC23766 and ethanol was not additive (not significantly different compared to either treatment alone). In contrast, exposure of RAW264.7 cells to C3 failed to alter FcγR-mediated actin polymerization to the phagosome. The combination of ethanol and C3 pretreatment lowered actin polymerization to the phagosome by 40% (p<0.05). This magnitude of reduction was not different from that of the of suppression seen following ethanol exposure alone. These data suggest that Rac is more critical to FcγR-mediated actin polymerization during phagocytosis than Rho, and that there is no synergistic effect of the Rac inhibitor and ethanol on this process.

Figure 8.

The importance of Rac and Rho in actin polymerization during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. RAW264.7 cells were cultured with 50 mM ethanol for 3 hours, NSC23766 (100 μM for 30 minutes), C3 (0.1 μg/ml) for 3 hours, or the combination of ethanol plus NSC23766, or ethanol plus C3. Inhibition of Rac, but not Rho, suppressed actin polymerization to the phagosome to the extent that ethanol alone did. The combination of ethanol and either C3 or NSC23766 did not inhibit actin polymerization more severely than ethanol alone. *p<0.05 compared to control. Results are the average of 3 independent experiments. Each experiment consisted of 30–60 phagocytic cells per condition.

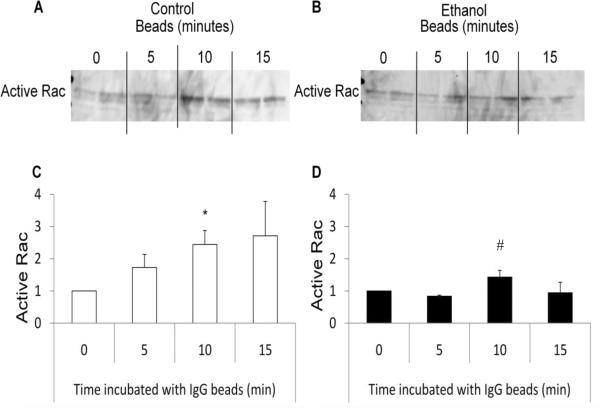

Ethanol decreased peak Rac activity during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis

The importance of Rac in the actin polymerization stage of phagocytosis was observed above, but the effect of ethanol pretreatment on its activation during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis has yet to be elucidated. To further examine this, RAW264.7 cells were cultured with IgG-coated beads and Rac activity was examined. We found a 150% increase in Rac activity at 10 minutes after the addition of bead (Figure 9). Exposing RAW264.7 cells to 50 mM ethanol 3 hours prior to the addition of beads reduced the peak Rac activity by 40%. This blunted Rac activition may explain the impaired phagocytic function of following ethanol exposure.

Figure 9.

Effect of ethanol on Rac activation during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to control media or media containing 50 mM ethanol for three hours were co-cultured with IgG coated beads to initiate FcγR-mediated phagocytosis for 0, 5, 10, or 15 minutes. Cells were subsequently lysed and active Rac was pulled down using GST-RacPAK-PBD, followed by probing with an antibody against total Rac via western blot analysis (A and B). Blots were quantified by after 0, 5, 10, and 15 minutes of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in control (C) and ethanol (D) exposed RAW264.7 cells. *p<0.05 compared to 0 minutes, # p<0.05 compared to 0 and 5 minutes. Data are the average of 4 independent experiments, each column represents an individual sample.

Small GTPases utilize GEFs as a primary source of enhancing GDP catalysis to GTP. Additionally, VavGEF has previously been shown to be utilized during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis [41]. Therefore, we sought to determine the effects of ethanol on the binding of VavGEF to Rac during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. There was a 2-fold increase in Vav binding to Rac at 10 minutes after the addition of IgG-coated beads regardless of ethanol exposure (data not shown). The similarity in Vav binding to Rac in cells cultured with or without ethanol prior to the addition of IgG-coated beads suggests an alternative mechanisms of small GTPase control by which ethanol suppresses Rac activation, possibly including other GEFs, GAPs, or GDIs. Additional investigation is warranted to further elucidate the mechanism(s) involved.

Discussion

In the higher eukaryotic systems, phagocytosis has evolved as a means of clearing pathogens, apoptotic cells, and cellular debris. This is accomplished by professional phagocytes, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, though other cells have been shown to have some phagocytic potential [42]. Through the internalization and processing of pathogens, the host can link the innate with the adaptive immune system by expressing antigen on major histocompatibility complex molecules [43]. The process of phagocytosis is critical for clearance of infectious organisms and a defect in leukocyte phagocytosis results in an inability to defend oneself from infection [44–45].

Both clinical and laboratory studies have shown that the exposure to alcohol results in complete or partial loss of phagocytosis [8, 10–13, 46–47]. Our current study supports and extends these observations by elucidating mechanisms by which ethanol attenuates this important function. Suppression of macrophage phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa was observed at 3 hours, but, like phagocytosis of IgG-coated beads, was not significantly impaired after 0.5 or 1.5 hours of ethanol exposure, nor after 6 or 24 hours of ethanol exposure. The time points prior to 3 hours may have been an insufficient amount of time for ethanol to affect molecular mechanisms of phagocytosis. On the contrary, at 6 and 24 hours after the initial ethanol exposure likely provided ample time for the cell to metabolize the ethanol and recover from its suppressive effects. In contrast to our later time points, Morland's group showed that a single dose of ethanol in vitro suppressed the ability of monocytes to internalize Candida (C.) albicans out to 24 hours after initial exposure [10]. Interestingly, 7 days after the original exposure of ethanol, monocytes exhibited a compensatory ability to clear C. albicans. However, daily replacement of ethanol in the media out to 7 days resulted in the impaired phagocytosis seen at earlier time points, again supporting our observations that ethanol transiently induced suppression of macrophage phagocytosis. It is important to note the relevance of alcohol exposure levels in laboratory studies and how those blood alcohol concentrations mimic what is observed in clinical settings, such as the emergency room of hospitals. Blood alcohol levels can reach levels of 100 mM (460 mg/dl BAC equivalent) in binge drinkers and alcohol abusers, but less often in social drinkers and rarely as a first time exposure. A Pittsburg study showed typical BAC levels in patients ranged from 22–460 mg/dl (with a mean of 226 mg/dl) [48], comparable to what is observed at Loyola University Hospital (unpublished observations), and levels that far exceed those used in the present study.

The receptors associated with phagocytosis are numerous, and include Fc, complement, scavenger, mannose, and some even suggest Toll-like receptors [22, 49]. In the present study, measurement of the three FcγRs (FcγRI, FcγRII, and FcγRIII), as well as other receptors, such as macrophage mannose receptor, TLR4, and the complement receptor (CD11b and CD18), showed no variation after 3 hours of in vivo or in vitro ethanol exposure (data not shown). Though receptor expression levels are unaltered following exposure to ethanol, studies have shown that ethanol can inhibit receptor (TLR4 and CD14) aggregation in lipid rafts [16, 50–51]. Currently there is no direct evidence suggesting that ethanol alters FcR aggregation, however, this is a possible mechanisms that could account for the reduction in phagocytosis reported herein. Since previous evidence suggested ethanol suppressed FcγR-mediated phagocytosis [10], we chose to focus our studies on this pathway. Because multiple receptors can mediate the host phagocytic response to a pathogen, and activation of these receptor pathways, such as TLR4 and MAPK signaling, have been shown to be attenuated by ethanol [4, 15, 49], we devised a method to isolate of the FcγR pathway. The use of IgG-coated latex beads allowed us to limit the effects of ethanol on this specific pathway, eliminating interference from other pathways that induce a phagocytic response or influence this pathway through signaling crosstalk.

The binding and clustering of the FcγR at the site of the pathogen/host interaction results in phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) and subsequent Src and Syk binding and phosphorylation [52–53]. Studies have reported that focal adhesion molecules, including paxillin and vinculin, associate with this complex [21–22]. In parallel to phagocytic adhesion formation, organized actin polymerization at the phagosome requires activation of the small Rho family of GTPases [54]. Influence of the small GTPases in actin regulation, specifically controlling actin contraction, polymerization, and anchoring, is critical during phagocytosis due to their intimate role in inducing membrane ruffling, lamellipodial extensions, and particle engulfment. Together, formation of the phagosomal adhesion complex and actin recruitment function in concert to swiftly internalize a foreign pathogen. In our model of phagocytosis, adhesion and actin polymerization was studied at 5 to 20 minutes following FcγR activation, which is consistent with other phagocytosis models that examine these parameters from 7 to 30 minutes following receptor activation [22, 29, 55]. At 20 minutes after addition of IgG coated beads, we find that ethanol reduced FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, actin polymerization, in alveolar macrophages and RAW264.7 cells. Previous reports have shown that ethanol has an effect on actin polymerization, though not in the context of phagocytosis [56–58]. For example, Guasch et al. demonstrated that ethanol reorganized actin distribution in astrocytes [27]. Though alteration of Rho activity may have an effect on the actin cytoskeleton as this group has suggested, it is unlikely to play a role in our model as Rho is primarily involved in complement-mediated phagocytosis and suggested to be less important in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis [29–30]. Evidence indicates that Rac is the dominant small GTPase during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis [55, 59–60]. Additionally, the use of the Rho inhibitor, C3, in our study, did not alter actin polymerization to the phagosome, whereas NSC23766 significantly blunted FcR-mediate actin recruitment, revealing the relative importance of the the small GTPases in this process. Rac is also known to have a regulatory role on actin polymerization, specifically during lamellipodial extension [61]. With this in mind, we propose that ethanol exposure results in dysregulation of Rac activity and subsequent actin polymerization during the process of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. Alternatively, a loss of activation of the actin scaffold protein vinculin could account for the decrease in actin polymerization at the site of the phagosome [62–63].

In the present studies, phosphorylation of vinculin during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis was inhibited in cells exposed to ethanol compared to control conditions. However, IgG-induced paxillin phosphorylation occurred as efficiently in ethanol-exposed macrophages as those cultured in the absence of ethanol. Though adhesion maturation induced by a phagocytic receptor has not been previously explored following exposure to ethanol, others have described focal adhesion formation during phagocytosis in the absence of ethanol, or focal adhesions at the level of the substrate in response to ethanol exposure [22, 28, 64–67]. Studies by Greenberg et al. showed that paxillin was phosphorylated during Fc-receptor mediated phagocytosis but that this was independent on focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation [67]. They also noted that disruption of the actin cytoskeleton using cytochalasin D did not affect the phosphorylation of paxillin during this process. Other reports documented localization of paxillin to the phagosome and phosphorylation of the protein in the cytoplasmic fraction of the cell during phagocytosis of IgG or complement opsonized beads [22, 65]. In other studies, vinculin redistributed to the site of Shigella flexneri, FcγR-, and CR3-mediated phagosomes [22, 64]. The ability of vinculin to bind to F-actin and talin, along with its interactions with PI(4,5)P2, make it a critical adhesion molecule during this process. These data support the importance of adhesion molecules during the process of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. The effects of ethanol on adhesion molecules at the level of the substrate have also been studied. Immunohistochemical evidence revealed that culture of the rat gastric mucosal cell line, RGM-1, with 50 mL/L ethanol for 15 minutes induced degradation and divergence of zonula adherens-associated vinculin [66]. This loss in vinculin resulted in a thinning of actin networks and zonula adherens-associated actin bundles at cell-cell contact sites. Although our data do not show any differences in total cellular vinculin, the loss of phosphorylated vinculin observed in our study could account for a reduction in the scaffold for actin and other molecules. Paxillin expression and organization has been shown to be effected by ethanol in primary culture astrocytes from 21-day old rat fetuses. Exposure of these cells to a relatively high levels of ethanol (100 mM) for one hour triggered paxillin reorganization to the cell periphery when cells were not in contact with each other, and a dramatic decrease in paxillin content when cells were densely packed [28]. Though our study did not show any differences in paxillin phosphorylation during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis following exposure to ethanol, this may be due to the lower ethanol concentration used in our study compared that of Minambres' group. Additionally, the similarity of paxillin phosphorylation during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis between control and ethanol exposed cells suggests, but is not limited, to two mechanisms of ethanol-induced adhesion modifications. First, ethanol may be inhibiting vinculin phosphorylation by modifying the molecules responsible for vinculin phosphorylation, such as focal adhesion kinase. Second, ethanol may be suppressing the actin contraction that occurs after binding to vinculin. This, in turn, would result in the loss of the open conformation of vinculin, and subsequent exposure to additional phosphorylation sites. Though the effects of ethanol on the regulation of adhesion molecules during phagocytosis has not been previously investigated, future studies are warranted to investigate the direct molecular role of ethanol-induced suppression of phagosomal adhesion.

Despite the identified role for small GTPase activity in phagocytosis, the regulation of small these molecules during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis has not been the focus of many studies. The recruitment of the RacGEF Vav was observed during phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized erythrocytes by the J774A.1 murine macrophage cell line, but not C3bi-coated erythrocytes [41]. Moreover, suppression of Vav by dominant negative Vav transfection, showed inhibition of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis to a similar extent observed by blocking Rac of Cdc42. The use of a dominant negative Vav did not block complement-mediated phagocytosis. With the use of the dominant negative Cdc42 transfection, the authors also demonstrated that Rac recruitment and activation was independent of Cdc42 activity during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. Though our study did not find that ethanol altered Vav binding to Rac during this process, the regulation of small GTPase are not limited to GEFs, but can also be influenced by RhoGDIs and RhoGAPs.

The mechanism(s) responsible for the suppressive effects of acute ethanol on FcγR-mediated phagocytosis have remained elusive prior to this study. Herein, we report for the first time that acute ethanol exposure suppressed FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by reducing phagosomal adhesion maturation, specifically vinculin phsosphorylation, and subsequent actin polymerization, which can be explained by a loss of Rac activation during phagocytosis. Additionally, though there is controversy regarding the specific Rho family GTPase playing the dominant role in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, our data in primary culture alveolar macrophages and RAW264.7 cells, indicate that Rac is the main small GTPase. This conclusion is based on two observations 1) the ethanol-mediated decrease in phagocytosis paralleling suppressed Rac activity and 2) the decreased phagocytosis seen after exposure of cells to a Rac-specific inhibitor. Inhibition of the formation of the adhesion complex during phagocytosis would underscore its importance in inducing actin polymerization and would strengthen our study. Unfortunately, there are no specific inhibitors that target phagosomal adhesion formation which would maintain stability in cell adhesion. Phosphorylation of the Fc receptors following ethanol exposure would be an ideal starting point during phagocytosis. Following aggregation of the Fc receptors, there is phosphorylation of either activating ITAMs or the inhibitory immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs), which may be affected by ethanol, ultimately influencing subsequent downstream mechanisms. However, to our knowledge there is no phosphorylated antibody specific for the various mouse Fc receptors. Alternatively, global tyrosine phosphorylation can be measured during phagocytosis and ethanol exposure. Future studies should be performed to confirm whether these findings are limited to the FcγRs or if they hold true in other modes of phagocytosis. Small GTPases and their control of the actin cytoskeleton have been known to modulate many cellular functions including phagocytosis, chemotaxis, cytokine production, and cell division [54, 68]. The suppression of Rac and subsequent actin polymerization following acute ethanol exposure during phagocytosis may provide mechanistic insight into other cellular function known to be altered after ethanol exposure. Examining these mechanisms may enhance our understanding of immune cells respond to exposure to ethanol, but also may allow the development of treatments for the immunosuppressive effects of ethanol and other agents.

Highlights

-

1)

In vivo ethanol attenuates P. oeruginosis phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages

-

2)

Acute ethanol suppresses vinculin phosphorylation during Fcrfi. phagosytosis

-

3)

Actin polymerization at phagosome is inhibited with prior ethanol exposure

-

4)

Lower Rac, but not Rho, activity can explain the decreased phagosome maturatio

-

5)

Paxillin phosphorylation or VavGEF were not altered following ethanol exposure

Summary Sentence: Acute ethanol inhibits phagocytosis and FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by suppressing Rac activity, vinculin phosphorylation and actin polymerization in macrophages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Aleah Brubaker and Dr. Shegufta Mahbub for critical evaluation of the manuscript. We also appreciate and thank Pat Simms for assistance with our flow cytometry studies. Thanks to the members of Loyola University Alcohol Research Program for thoughtful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 AA12034 (EJK), National Institutes of Health F31 AA017027 (JK), Illinois Excellence in Academic Medicine Grant, and Ralph and Marian C. Falk Research Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship J.K. designed and performed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; E.M. and C.D. provided the EGFP-P. aeruginosa and assisted with technical aspects of the study; L.R. assisted with the technical aspects and the mouse husbandry of the study; E.J.K supervised the work, interpreted the results, and edited the manuscript.

References

- [1].Cook RT. Alcohol abuse, alcoholism, and damage to the immune system--a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1927–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moss M, Burnham EL. Chronic alcohol abuse, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S207–212. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057845.77458.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goral J, Choudhry MA, Kovacs EJ. Acute ethanol exposure inhibits macrophage IL-6 production: role of p38 and ERK1/2 MAPK. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:553–559. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Szabo G. Monocytes, alcohol use, and altered immunity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:216S–219S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-199805001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gamble L, Mason CM, Nelson S. The effects of alcohol on immunity and bacterial infection in the lung. Med Mal Infect. 2006;36:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Guidot DM, Hart CM. Alcohol abuse and acute lung injury: epidemiology and pathophysiology of a recently recognized association. J Investig Med. 2005;53:235–245. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Happel KI, Nelson S. Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:428–432. doi: 10.1513/pats.200507-065JS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goral J, Karavitis J, Kovacs EJ. Exposure-dependent effects of ethanol on the innate immune system. Alcohol. 2008;42:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Morland B, Morland J. Reduced Fc-receptor function in human monocytes exposed to ethanol in vitro. Alcohol Alcohol. 1984;19:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rimland D, Hand WL. The effect of ethanol on adherence and phagocytosis by rabbit alveolar macrophages. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;95:918–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zuiable A, Wiener E, Wickramasinghe SN. In vitro effects of ethanol on the phagocytic and microbial killing activities of normal human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Clin Lab Haematol. 1992;14:137–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1992.tb01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Karavitis J, Murdoch EL, Gomez CR, Ramirez L, Kovacs EJ. Acute ethanol exposure attenuates pattern recognition receptor activated macrophage functions. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28:413–422. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Joshi PC, Applewhite L, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J, Fernandez AL, Eaton DC, Brown LA, Guidot DM. Chronic ethanol ingestion in rats decreases granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor expression and downstream signaling in the alveolar macrophage. J Immunol. 2005;175:6837–6845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goral J, Kovacs EJ. In vivo ethanol exposure down-regulates TLR2-, TLR4-, and TLR9-mediated macrophage inflammatory response by limiting p38 and ERK1/2 activation. J Immunol. 2005;174:456–463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Szabo G, Dolganiuc A, Dai Q, Pruett SB. TLR4, ethanol, and lipid rafts: a new mechanism of ethanol action with implications for other receptor-mediated effects. J Immunol. 2007;178:1243–1249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mandrekar P, Bala S, Catalano D, Kodys K, Szabo G. The opposite effects of acute and chronic alcohol on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation are linked to IRAK-M in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183:1320–1327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blasi F, Tarsia P, Aliberti S. Strategic targets of essential host-pathogen interactions. Respiration. 2005;72:9–25. doi: 10.1159/000083394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Raghavan M, Bjorkman PJ. Fc receptors and their interactions with immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:181–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gessner JE, Heiken H, Tamm A, Schmidt RE. The IgG Fc receptor family. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:231–248. doi: 10.1007/s002770050396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Allen LA, Aderem A. Mechanisms of phagocytosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Garin J, Diez R, Kieffer S, Dermine JF, Duclos S, Gagnon E, Sadoul R, Rondeau C, Desjardins M. The phagosome proteome: insight into phagosome functions. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:165–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Trost M, English L, Lemieux S, Courcelles M, Desjardins M, Thibault P. The phagosomal proteome in interferon-gamma-activated macrophages. Immunity. 2009;30:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zigmond SH, Hirsch JG. Effects of cytochalasin B on polymorphonuclear leucocyte locomotion, phagocytosis and glycolysis. Exp Cell Res. 1972;73:383–393. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Axline SG, Reaven EP. Inhibition of phagocytosis and plasma membrane mobility of the cultivated macrophage by cytochalasin B. Role of subplasmalemmal microfilaments. J Cell Biol. 1974;62:647–659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.62.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Guasch RM, Tomas M, Minambres R, Valles S, Renau-Piqueras J, Guerri C. RhoA and lysophosphatidic acid are involved in the actin cytoskeleton reorganization of astrocytes exposed to ethanol. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:487–502. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Minambres R, Guasch RM, Perez-Arago A, Guerri C. The RhoA/ROCK-I/MLC pathway is involved in the ethanol-induced apoptosis by anoikis in astrocytes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:271–282. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Caron E, Hall A. Identification of two distinct mechanisms of phagocytosis controlled by different Rho GTPases. Science. 1998;282:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cox D, Chang P, Zhang Q, Reddy PG, Bokoch GM, Greenberg S. Requirements for both Rac1 and Cdc42 in membrane ruffling and phagocytosis in leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1487–1494. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].May RC, Caron E, Hall A, Machesky LM. Involvement of the Arp2/3 complex in phagocytosis mediated by FcgammaR or CR3. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:246–248. doi: 10.1038/35008673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].May RC, Machesky LM. Phagocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1061–1077. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Massol P, Montcourrier P, Guillemot JC, Chavrier P. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis requires CDC42 and Rac1. EMBO J. 1998;17:6219–6229. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Castellano F, Montcourrier P, Guillemot JC, Gouin E, Machesky L, Cossart P, Chavrier P. Inducible recruitment of Cdc42 or WASP to a cell-surface receptor triggers actin polymerization and filopodium formation. Curr Biol. 1999;9:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Castellano F, Montcourrier P, Chavrier P. Membrane recruitment of Rac1 triggers phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 17):2955–2961. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shi L, Kishore R, McMullen MR, Nagy LE. Chronic ethanol increases lipopolysaccharide-stimulated Egr-1 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages: contribution to enhanced tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14777–14785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108967200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gomez CR, Karavitis J, Palmer JL, Faunce DE, Ramirez L, Nomellini V, Kovacs EJ. Interleukin-6 contributes to age-related alteration of cytokine production by macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:475139. doi: 10.1155/2010/475139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shen Y, Kawamura I, Nomura T, Tsuchiya K, Hara H, Dewamitta SR, Sakai S, Qu H, Daim S, Yamamoto T, Mitsuyama M. Toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rac1 activation facilitates the phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2857–2867. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].de Oliveira CA, Mantovani B. Latrunculin A is a potent inhibitor of phagocytosis by macrophages. Life Sci. 1988;43:1825–1830. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Malawista SE, Gee JB, Bensch KG. Cytochalasin B reversibly inhibits phagocytosis: functional, metabolic, and ultrastructural effects in human blood leukocytes and rabbit alveolar macrophages. Yale J Biol Med. 1971;44:286–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Patel JC, Hall A, Caron E. Vav regulates activation of Rac but not Cdc42 during FcgammaR-mediated phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1215–1226. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arlein WJ, Shearer JD, Caldwell MD. Continuity between wound macrophage and fibroblast phenotype: analysis of wound fibroblast phagocytosis. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1041–1048. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jutras I, Desjardins M. Phagocytosis: at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:511–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dahmer MK, Randolph A, Vitali S, Quasney MW. Genetic polymorphisms in sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:S61–73. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161970.44470.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yuan FF, Marks K, Wong M, Watson S, de Leon E, McIntyre PB, Sullivan JS. Clinical relevance of TLR2, TLR4, CD14 and FcgammaRIIA gene polymorphisms in Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:268–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Castro A, Lefkowitz DL, Lefkowitz SS. The effects of alcohol on murine macrophage function. Life Sci. 1993;52:1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90059-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schopf RE, Trompeter M, Bork K, Morsches B. Effects of ethanol and acetaldehyde on phagocytic functions. Arch Dermatol Res. 1985;277:131–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00414111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Winek CL, Wahba WW, Windisch RM, Winek CL., Jr. Serum alcohol concentrations in trauma patients determined by immunoassay versus gas chromatography. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;139:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Anand RJ, Kohler JW, Cavallo JA, Li J, Dubowski T, Hackam DJ. Toll-like receptor 4 plays a role in macrophage phagocytosis during peritoneal sepsis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.01.023. discussion 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Dolganiuc A, Bakis G, Kodys K, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Acute ethanol treatment modulates Toll-like receptor-4 association with lipid rafts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dai Q, Pruett SB. Different effects of acute and chronic ethanol on LPS-induced cytokine production and TLR4 receptor behavior in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunotoxicol. 2006;3:217–225. doi: 10.1080/15476910601080156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cox D, Greenberg S. Phagocytic signaling strategies: Fc(gamma)receptor-mediated phagocytosis as a model system. Semin Immunol. 2001;13:339–345. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Daeron M. Fc receptor biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:203–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Niedergang F, Chavrier P. Regulation of phagocytosis by Rho GTPases. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;291:43–60. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27511-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Swanson JA, Hoppe AD. The coordination of signaling during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:1093–1103. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Allansson L, Khatibi S, Olsson T, Hansson E. Acute ethanol exposure induces [Ca2+]i transients, cell swelling and transformation of actin cytoskeleton in astroglial primary cultures. J Neurochem. 2001;76:472–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dai Q, Pruett SB. Ethanol suppresses LPS-induced Toll-like receptor 4 clustering, reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and associated TNF-alpha production. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1436–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zhang P, Spitzer JA. Acute ethanol administration modulates leukocyte actin polymerization in endotoxic rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:779–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Greenberg S. Modular components of phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:712–717. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Koh AL, Sun CX, Zhu F, Glogauer M. The role of Rac1 and Rac2 in bacterial killing. Cell Immunol. 2005;235:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hall A. Rho GTPases and the control of cell behaviour. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:891–895. doi: 10.1042/BST20050891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Janssen ME, Kim E, Liu H, Fujimoto LM, Bobkov A, Volkmann N, Hanein D. Three-dimensional structure of vinculin bound to actin filaments. Mol Cell. 2006;21:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Johnson RP, Craig SW. F-actin binding site masked by the intramolecular association of vinculin head and tail domains. Nature. 1995;373:261–264. doi: 10.1038/373261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kadurugamuwa JL, Rohde M, Wehland J, Timmis KN. Intercellular spread of Shigella flexneri through a monolayer mediated by membranous protrusions and associated with reorganization of the cytoskeletal protein vinculin. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3463–3471. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3463-3471.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kedzierska K, Vardaxis NJ, Jaworowski A, Crowe SM. FcgammaR-mediated phagocytosis by human macrophages involves Hck, Syk, and Pyk2 and is augmented by GM-CSF. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:322–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bidel S, Mustonen H, Khalighi-Sikaroudi G, Lehtonen E, Puolakkainen P, Kiviluoto T, Kivilaakso E. Effect of the ulcerogenic agents ethanol, acetylsalicylic acid and taurocholate on actin cytoskeleton and cell motility in cultured rat gastric mucosal cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4032–4039. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Greenberg S, Chang P, Silverstein SC. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the gamma subunit of Fc gamma receptors, p72syk, and paxillin during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3897–3902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Fukata M, Nakagawa M, Kaibuchi K. Roles of Rho-family GTPases in cell polarisation and directional migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:590–597. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]