Abstract

Background

Despite well-established gender differences in adult smoking behaviors, relatively little is known about gender discrepancies in smoking behaviors among adolescents, and even less is known about the role of gender in smoking cessation among teen populations.

Method

The present study examined gender differences in a population of 755 adolescents seeking to quit smoking through the American Lung Association’s Not-On-Tobacco (N-O-T) program. All participants enrolled in the N-O-T program between 1998 and 2009. All participants completed a series of questionnaires prior to and immediately following the cessation intervention. Analyses examined gender differences in a range of smoking variables, cessation success and direct and indirect effects on changes in smoking behaviors.

Results

Females were more likely to have a parents, siblings and romantic partners who smokes, perceive those around them will support a cessation effort, smoke more prior to intervention if they have friends who smoke, and to have lower cessation motivation and confidence if they have a parent who smokes. Conversely, males were more likely to have lower cessation motivation and confidence and be less likely to quit if they have a friend who smokes.

Conclusions

Gender plays an important role in adolescent smoking behavior and smoking cessation. Further research is needed to understand how these differences may be incorporated into intervention design to increase cessation success rates among this vulnerable population of smokers.

1 Introduction

Despite an overall decrease in smoking prevalence since the 1970s (Nelson et al., 2008), recent data suggest that 20% of adolescents have smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days; more than half have tried cigarette smoking in their lifetimes (Eaton et al., 2008). Numerous studies reveal gender-based differences in smoking prevalence (Dube, Asman, Malarcher, & Carabollo, 2009), risk correlates (Gritz, Nielsen, & Brooks, 1996; Hamilton et al., 2006), cessation (Bjornson et al., 1995; Ellis, Perl, Davis, & Vichinsky, 2008; Perkins & Scott, 2008), and methods of smoking a cigarette (Melikian et al., 2007). However, much of this work has focused on adult or young adult populations. Comparatively fewer studies have examined these differences among adolescents, and even fewer have specifically explored gender differences related to teen smoking cessation.

Research has identified several predictors of adolescent cessation, such as parental smoking, level of addiction, smoking frequency, readiness and intentions to quit (Bagot, Heishman, & Moolchan, 2007; Kleinjan et al., 2009; Myers & MacPherson, 2009; Sargent, Mott, & Stevens, 1998; Zhu, Sun, Billings, Choi, & Malarcher, 1999). Many of these studies, however, did not explore whether these associations differed by gender; a potentially critical factor to explore given research that shows adolescent males and females experience differential success and motivation in quitting (MacPherson & Myers, 2010; Paavola, Vartiainen, & Puska, 2001; Patton et al., 1998; Thiri Aung, Hickman Iii, & Moolchan, 2003). The present study examined gender differences in six categories previously found to be associated with smoking cessation among adolescents: 1) smoking history, 2 readiness to quit, 3) social contexts, 4) perceived support for cessation, 5) nicotine dependence, and 6) attitudes toward smoking. Additionally, this study examined direct and indirect effects of these variables on smoking behavior by gender.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were 755 adolescents who participated in studies of the American Lung Association’s Not On Tobacco (N-O-T) cessation program between 1998 and 2009. Participants represented five states (New Jersey, West Virginia, Florida, North Carolina, and Wisconsin) and ranged between 14 and 19 years (M = 16.17; SD = 1.13). The sample was 58% female and 85% Caucasian. Males (M = 16.12 years; SD = 1.27) were slightly older than females (M = 15.87 years; SD = 1.23). All procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Measures

The data were collected at the time of enrollment in the cessation program (“baseline”) and again following program completion, approximately 3-months post-baseline.

2.21 Smoking History and Dependence

Smoking history was collected for each participant, including: 1) age of first cigarette use, 2) if participant had made quit attempts, 3) nicotine dependence using the Modified Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (mFTQ) (Prokhorov, Koehly, Pallonen, & Hudmon, 1998), and 4) cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) on weekdays and weekends.

2.2.3 Social Context

Participants were asked about the smoking status of their parents, siblings, friends, and, if they had a current romantic partner, they were asked the smoking status of that person. Additionally, participants were asked if each of these people would support their cessation efforts.

2.2.4 Intervention readiness

The motivation to quit and the confidence in the ability to quit were assessed on a fivepoint scale for each participant (1=not motivated; 5=highly motivated).

2.2.5 Reasons for smoking

Participants responded to items assessing their perceived reasons for smoking, including: 1) positive reinforcement (smoking for the positive effects), 2) negative reinforcement (smoking to avoid negative effects such as withdrawal), 3) addiction (smoking because of nicotine addiction), and 4) negative consequences (smoking less to avoid negative outcomes). Items are derived from the Subjective Expected Utility questionnaire (Branstetter, Grady, Horn, & Dino, 2010).

3. Results

3.1 Differences in baseline variables

Analyses reveal a number of gender differences in smoking history, social environment, perceived support for cessation, nicotine dependence, and reasons for smoking, see Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Differences in Predictors Associated with Smoking Cessation, by Gender.

| Predictor | Gender | Statistic | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | |||

| Smoking History | ||||

| CPD Weekday at baseline | 11.35 (9.66) | 13.31 (12.66) | t=−7.94 | <.001 |

| CPD Weekend at baseline | 17.53 (13.23) | 19.05 (14.33) | t=−6.06 | <.001 |

| Past quit attempt | 81% | 75% | χ2=30.47 | <.001 |

| Length of time being a current smoker (months) | 43.86 (23.89) | 45.43 (27.27) | t=−2.51 | .01 |

| Readiness to Quit | ||||

| Motivation to quit | 3.08 (.96) | 3.06 (1.00) | t= .67 | .50 |

| Confidence in ability to quit | 2.95 (.95) | 2.96 (1.00) | t=−33 | .74 |

| Social Environment | ||||

| At least one parent smokes | 73% | 68% | χ2=11.60 | .001 |

| At least one sibling smokes | 59% | 55% | χ2=6.34 | .04 |

| Have a boy/girlfriend | 67% | 47% | χ2=33.14 | <.001 |

| Boy/girlfriend smokes | 70% | 61% | χ2=26.20 | <.001 |

| Close friend smokes | 95% | 94% | χ2=20 | .21 |

| Perceived Support for Cessation | ||||

| Parents will be supportive | 80% | 77% | χ2=4.07 | .13 |

| Friends will be supportive | 78% | 56% | χ2=45.55 | <.001 |

| Sibling will be supportive | 68% | 58% | χ2=7.77 | .02 |

| Boy/girlfriend will be supportive | 79% | 69% | χ2=11.37 | .003 |

| Nicotine Dependence | ||||

| Nicotine dependence (FTQ) | 5.77 (1.96) | 5.93(1.97) | t= −1.32 | .19 |

| Smoke within 30 minute of waking | 63% | 69% | χ2=5.77 | .02 |

| First cigarette of the day most satisfying | 52% | 57% | χ2=7.67 | .02 |

| Attitudes/Beliefs about Smoking | ||||

| Positive reinforcement | 2.27 (.77) | 2.30 (.89) | t=−.45 | .65 |

| Negative reinforcement | 4.17 (.73) | 3.78 (.94) | t=6.12 | <.001 |

| Addiction | 3.18 (.77) | 2.90 (.87) | t=4.40 | <.001 |

| Consequences | 3.77 (.66) | 3.54 (.75) | t=6.37 | <.001 |

3.2 Cessation

Logistic regression models found gender is not a predictor of cessation outcome (self-reported as “quit” or “not quit” in the last 7-days), b = .097, p = .08, Exp(B) = 1.10. Likewise, in linear regression models, gender did not predict changes in CPD from baseline to post-intervention (i.e., CPD) among those who did not quit, b = .21, t = 1.05, p = .29. For females, smoking within 30 minute of waking, b= 4.10, t = 3.57, p <.001, and low confidence in the ability to quit, b = −1.75, t=−3.15, p = .002, predicted increases in CPD from baseline, F(15, 166) = 8.24, p = .001. For male, only prior quit attempts, b=−7.40, t=−3.53, p = .001 predicted increases in CPD from baseline, model F(15, 73) = 3.37, p < .001.

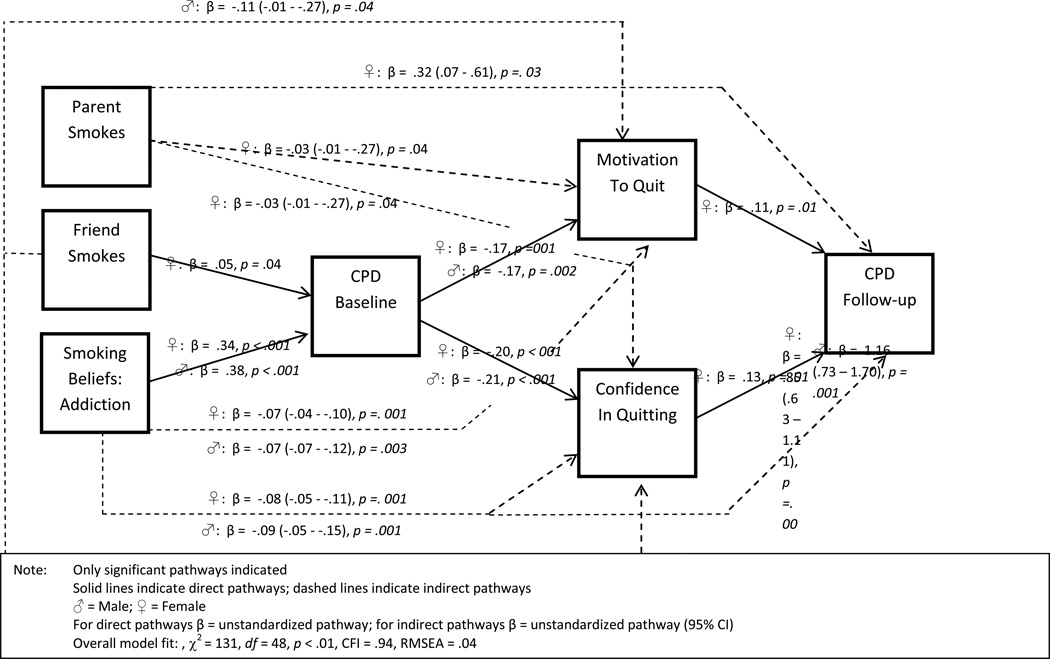

3.3 Direct and Indirect Effects

To examine direct and indirect gender effects on changes in smoking behaviors, we use structural equation models (SEM). To test multiple mediation effects, we used bias-corrected bootstrapping to provide the strongest possible confidence intervals for each mediation pathway (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Initial models included reasons for smoking, perceived support for cessation, social environment, smoking history and nicotine dependence as predictors of baseline CPD, readiness to quit, and changes in CPD post-intervention, see variables listed in Table 1. The final model in Figure 1 displays only significant pathways. SEM models were evaluated using multi-group analyses allowing for comparison of differences in direct and indirect pathways between males and females. Overall model fit was evaluated using chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Bentler, 2007).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model for Changes in Cigarettes Per Day Post-Intervention

3.3.1 Cessation Outcome

The model fit for cessation outcomes was acceptable, χ2 = 152.41, df = 48, p < .001, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .04. For direct effects, reasons for smoking (addiction) was related to baseline CPD for both males, b=3.99, SE=.006, p < .001, and females, b=3.35, SE=.39, p < .001. Additionally, baseline CPD was related to motivation to quit, (males: b= −.02, SE=.006, p = .002; females: −.02, SE=.004, p < .001) and confidence in quitting (males: b=−.02, SE=.006, p=.003; females: −.02, SE=.004, p < .001) for males and females. However, whereas baseline CPD was related to quit outcomes for females, b=.006, SE=.002, p < .001, only motivation to quit was related to quit outcome for males, b=−.08, SE=.03, p=.003.

For females, having a parent who smokes, b=.01, 95% CI: .002 – .02), p=.03, and reasons for smoking (addiction), b=.02, 95% CI: .013 – .03 0, p =.001, had significant indirect effects on cessation outcome. For males, having a friend who smokes, b=.04, 95% CI: .004 – .09, p=.04, and reasons for smoking (addiction), b=.02, 95% CI: .005 – .04, p=.03, had significant indirect effects on cessation.

3.3.2 Changes in CPD

Results reveal gender differences in direct and indirect pathways influencing changes in CPD post-intervention, see Figure 1. For females having a friend who smokes had a direct influence on the baseline CPD. Interestingly, motivation to quit and confidence in quitting had direct effects on changes CPD post-intervention for females only. For males, having friends who smoke had an indirect effect on both motivation to quit and confidence in quitting. For females having a parent who smokes had indirect effects on motivation to quit, confidence in quitting and changes in CPD post-intervention. Having a parent who smokes had neither direct nor indirect effects for males. In fact, the only variable that had an effect (indirect) on changes in CPD post-intervention for males was reasons for smoking (addiction).

4. Discussion

The present study highlights gender differences in individual and contextual variables that may influence cessation. Numerous baseline gender differences were founds in smoking behaviors. Many of these findings, such as differences in length of smoking history and the number of CPD, are not surprising and are consistent with previous research. Other findings, however, reveal suggest important gender differences in teen smokers seeking to quit. For example, it was found that females were consistently surrounded by more smokers in their social environments: females were more likely to have parents, siblings and romantic partners who smoke. Moreover, whereas both males and females had equal perceptions that parents would be supportive of a quit attempt, females were more likely to perceive that peers, siblings and romantic partners would be supportive. Finally, although males and females had similar scores on the mFTQ, males were more likely to smoke sooner after waking and to rate the first cigarette of the day as the most satisfying – two indicators reflecting greater nicotine uptake and dependence (e.g., (Muscat, Stellman, Caraballo, & Richie, 2009).

The influence of peers is a long-established predictor smoking behavior (Burt & Peterson, 1998); comparatively less is known, however, about romantic partners’ effects on adolescent smoking. Our results illustrate important gender differences among teens who smoke with regard to having a romantic partner, and whether their romantic partner smokes. Over half of male smokers seeking to quit did not have a romantic partner (53%); conversely well over half of the female smokers did have a romantic partner (67%), and a female’s romantic partner was significantly more likely to smoke. Previous research has identified a link between dating and smoking (Martin et al., 2007; Wang, 2001), intention to smoke (Tucker, 1985), and susceptibility to smoking update based on partner smoking status (Mermelstein, Colvin, & Klingemann, 2009). Future studies should further explore gender differences in the influence of romantic partners on smoking behaviors as well as cessation.

Our findings also demonstrated important gender differences on how key variables work together to influence smoking cessation outcomes. For example, it was found that parental smoking had strong indirect effects for females on motivation to quit, confidence in quitting and both cessation and changes in CPD post-intervention. However, parental smoking had no direct or indirect effects for males. Furthermore, having a friend who smokes had direct effects on baseline CPD for females; for males having a friend who smokes had indirect effects on motivation to quit, confidence in quitting, and cessation.

These results should be interpreted with attention to their limitations. First, our sample consisted of adolescent who actively seeking to quit; as such, selection bias may have occurred among the sample. Next, although N-O-T programs are structured with standardized curriculum for the participants and standardized training for the facilitators, program fidelity is a concern given the hundreds of N-O-T sessions combined to form the present dataset. Finally, all data collected were self-report data from a single participant, potentially resulting in some degree of bias.

Limitations notwithstanding, the present findings highlight the importance of addressing gender differences among youth smokers seeking to quit, and add support for gender-tailored adolescent cessation interventions. Future research is needed to further examine the mechanisms behind these gender differences and how these differences may be utilized in the modification and development of prevention and intervention efforts.

Research Highlights.

Females were consistently surrounded by more smokers in their social environments: females were more likely to have parents, siblings and romantic partners who smoke.

Whereas both males and females had equal perceptions that parents would be supportive of a quit attempt, females were more likely to perceive that peers, siblings and romantic partners would be supportive.

Although males and females had similar scores on the mFTQ, males were more likely to smoke sooner after waking and to rate the first cigarette of the day as the most satisfying – two indicators reflecting greater nicotine uptake and dependence.

Female smokers were more likely to have a romantic partner, and that romantic partner was more likely to smoke.

Among males, having friends who smoke had an indirect effect on both motivation to quit and confidence in quitting.

For females having a parent who smokes had indirect effects on motivation to quit, confidence in quitting and changes in the number of cigarettes per day post-intervention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bagot Kara S, Heishman Stephen J, Moolchan Eric T. Tobacco craving predicts lapse to smoking among adolescent smokers in cessation treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(6):647–652. doi: 10.1080/14622200701365178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(5):825–829. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson Wendy, Rand Cynthia, Connett John E, Lindgren Paula, Nides Mitchell, Pope Frances, O'Hara Peggy. Gender Differences in Smoking Cessation after 3 Years in the Lung Health Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(2):223–223. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstetter SA, Grady E, Horn K, Dino G. Development and validation of a subjective expected utility measure of adolescent smoking; Paper presented at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Baltimore, MD. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burt RD, Peterson AV., Jr Smoking cessation among high school seniors. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27(3):319–327. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Asman K, Malarcher A, Carabollo R. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation - United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(44):1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton Danice K, Kann Laura, Kinchen Steve, Shanklin Shari, Ross James, Hawkins Joseph, Wechsler Howell. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance -- United States, 2007. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(SS-4):1–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JA, Perl SB, Davis K, Vichinsky L. Gender differences in smoking and cessation behaviors among young adults after implementation of local comprehensive tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(2):310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Nielsen IR, Brooks LA. Smoking cessation and gender: the influence of physiological, psychological, and behavioral factors. Journal Of The American Medical Women's Association (1972) 1996;51(1–2):35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AS, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Cockburn MG, Unger JB, Cozen W, Mack TM. Gender differences in determinants of smoking initiation and persistence in California twins. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15(6):1189. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan Marloes, Engels Rutger CME, van Leeuwe Jan, Brug Johannes, van Zundert Rinka MP, van den Eijnden Regina JJM. Mechanisms of adolescent smoking cessation: Roles of readiness to quit, nicotine dependence, and smoking of parents and peers. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2009;99(1–3):204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Myers MG. Examination of a process model of adolescent smoking self-change efforts in relation to gender. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2010;19(1):48–65. doi: 10.1080/10678280903400644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Lommel K, Cox J, Kelly T, Rayens MK, Woodring JH, Omar H. Kiss and Tell: What Do We Know About Pre- and Early Adolescent Females Who Report Dating? A Pilot Study. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology. 2007;20(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikian Assieh A, Djordjevic Mirjana V, Hosey James, Zhang Jie, Chen Shuquan, Zang Edith, Stellman Steven D. Gender differences relative to smoking behavior and emissions of toxins from mainstream cigarette smoke. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(3):377–387. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein Robin J, Colvin Peter J, Klingemann Sven D. Dating and changes in adolescent cigarette smoking: Does partner smoking behavior matter? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(10):1226–1230. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Stellman SD, Caraballo RS, Richie JP. Time to first cigarette after waking predicts cotinine levels. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(12):3415. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Mark G, MacPherson Laura. Coping with temptations and adolescent smoking cessation: An initial investigation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(8):940–944. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson David E, Mowery Paul, Asman Kat, Pederson Linda L, O'Malley Patrick M, Malarcher Ann, Pechacek Terry F. Long-Term Trends in Adolescent and Young Adult Smoking in the United States: Metapatterns and Implications. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(5):905–915. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavola M, Vartiainen E, Puska P. Smoking cessation between teenage years and adulthood. Health Education Research. 2001;16(1):49–57. doi: 10.1093/her/16.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. The course of early smoking: a population-based cohort study over three years. Addiction. 1998;93(8):1251–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.938125113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins Kenneth A, Scott John. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(7):1245–1251. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Koehly LM, Pallonen UE, Hudmon KS. Adolescent nicotine dependence measured by the modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire at two time points. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1998;7(4):35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Mott LA, Stevens M. Predictors of smoking cessation in adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152(4):388–393. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiri Aung A, Hickman Iii, Norval J, Moolchan Eric T. Health and Performance Related Reasons for Wanting to Quit: Gender Differences Among Teen Smokers. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38(8):1095. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LA. Physical, psychological, social, and lifestyle differences among adolescents classified according to cigarette smoking intention status. The Journal Of School Health. 1985;55(4):127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1985.tb04099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Min Qi. Social Environmental Influences on Adolescents' Smoking Progression. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2001;25(4):418. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Sun J, Billings SC, Choi WS, Malarcher A. Predictors of smoking cessation in US adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(3):202–207. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]