Abstract

Background

Although it is agreed that a major polyploidy event, gamma, occurred within the eudicots, the phylogenetic placement of the event remains unclear.

Results

To determine when this polyploidization occurred relative to speciation events in angiosperm history, we employed a phylogenomic approach to investigate the timing of gene set duplications located on syntenic gamma blocks. We populated 769 putative gene families with large sets of homologs obtained from public transcriptomes of basal angiosperms, magnoliids, asterids, and more than 91.8 gigabases of new next-generation transcriptome sequences of non-grass monocots and basal eudicots. The overwhelming majority (95%) of well-resolved gamma duplications was placed before the separation of rosids and asterids and after the split of monocots and eudicots, providing strong evidence that the gamma polyploidy event occurred early in eudicot evolution. Further, the majority of gene duplications was placed after the divergence of the Ranunculales and core eudicots, indicating that the gamma appears to be restricted to core eudicots. Molecular dating estimates indicate that the duplication events were intensely concentrated around 117 million years ago.

Conclusions

The rapid radiation of core eudicot lineages that gave rise to nearly 75% of angiosperm species appears to have occurred coincidentally or shortly following the gamma triplication event. Reconciliation of gene trees with a species phylogeny can elucidate the timing of major events in genome evolution, even when genome sequences are only available for a subset of species represented in the gene trees. Comprehensive transcriptome datasets are valuable complements to genome sequences for high-resolution phylogenomic analysis.

Background

Gene duplication provides the raw genetic material for the evolution of functional novelty and is considered to be a driving force in evolution [1,2]. A major source of gene duplication is whole genome duplication (WGD; polyploidy), which involves the doubling of the entire genome. WGD has played a major role in the evolution of most eukaryotes, including ciliates [3], fungi [4], flowering plants [5-16], and vertebrates [17-19]. Studies in these lineages support an association between WGD and gene duplications [6,20], functional divergence in duplicate gene pairs [21,22], phenotypic novelty [23], and possible increases in species diversity [24,25] driven by variation in gene loss and retention among diverging polyploidy sub-populations [26-29].

There is growing consensus that one or more rounds of WGD played a major role early in the evolution of flowering plants [2,5,7-9,13,30,31]. Early synteny-based and phylogenomic analyses of the Arabidopsis genome revealed multiple WGD events [8,9]. The oldest of these WGD events was placed before the monocot-eudicot divergence, a second WGD was hypothesized to be shared among most, if not all, eudicots, and a more recent WGD was inferred to have occurred before diversification of the Brassicales [9]. Synteny analyses of the recently sequenced nuclear genomes of Vitis vinifera (wine grape, grapevine) [32] and Carica papaya (papaya tree) [7] provided more conclusive evidence for a somewhat different scenario in terms of the number and timing of WGDs early in the history of angiosperms. Each Vitis (or Carica) genome segment can be syntenic with up to four segments in the Arabidopsis genome, implicating two WGDs in the Arabidopsis lineage after separation from the Vitis (or Carica) lineage [7,12,32]. The more ancient one (β) appears to have occurred around the time of the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction [10]. Analyses of the genome structure of Vitis revealed triplicate sets of syntenic gene blocks [11,32]. Because the blocks are all similarly diverged, and thus were probably generated at around the same time in the past, the triplicated genome structure is likely to have been generated by an ancient hexaploidy event, possibly similar to the two successive WGDs likely to have produced Triticum aestivum [33]. Although the mechanism is not clear at this point, the origin of this triplicated genome structure is commonly referred to as gamma or γ (hereafter γ refers to the gamma event). Comparisons of available genome sequences for other core rosid species (including Carica, Populus, and Arabidopsis) and the recently sequenced potato genome (an asterid, Solanum tuberosum) show evidence of one or more rounds of polyploidy with the most ancient event within each genome represented by triplicated gene blocks showing interspecific synteny with triplicated blocks in the Vitis genome [7,11,34,35]. The most parsimonious explanation of these patterns is that γ occurred in a common ancestor of rosids and asterids, because all sequenced genomes within these lineages share a triplicate genome structure [12,35].

Despite this growing body of evidence from genome sequences, the phylogenetic placement of γ on the angiosperm tree of life remains equivocal (for example, [13]). As described above, the γ event is readily apparent in analyses of sequenced core eudicot genomes, and recent comparisons of regions of the Amborella genome and the Vitis synteny blocks indicate that the γ event occurred after the origin and early diversification of angiosperms [36]. In addition, comparisons of the Vitis synteny blocks with bacterial artificial chromosome sequences from the Musa (a monocot) genome provide weak evidence that γ postdates the divergence of monocots and eudicots [11].

As an alternative to synteny comparisons, a phylogenomic approach has also been used successfully to determine the relative timing of WGD events. By mapping paralogs created by a given WGD onto phylogenetic trees, we can determine whether the paralogs resulted from a duplication event before or after a given branching event [9]. In a recent study, Jiao et al. [5] used a similar strategy to identify two bouts of concerted gene duplications that are hypothesized to be derived from successive genome duplications in common ancestors of living seed plants and angiosperms. When using a phylogenomic approach, extensive rate variation among species could lead to incorrect phylogenetic inferences and then possibly also result in the incorrect placement of duplication events [11]. Gene or taxon sampling can reduce variation in branch lengths and the impact of long-branch attraction in gene tree estimates (for example, [37-39]). Therefore, effective use of the phylogenomic approach requires consideration of possible differences in substitution rates and careful taxon sampling to divide long branches that can lead to artifacts in phylogenetic analyses.

The availability of transcriptome data produced by both traditional (Sanger) and next-generation cDNA sequencing methods has grown rapidly in recent years [40,41]. In PlantGDB, very large Sanger EST datasets from multiple members of Asteraceae (for example, Helianthus annuus, sunflower) and Solanaceae (for example, S. tuberosum, potato), in particular, provide good coverage of the gene sets from the two largest asterid lineages. With advances in next-generation sequencing, comprehensive transcriptome datasets are being generated for an expanding number of species. For example, the Ancestral Angiosperm Genome Project has generated large, multi-tissue cDNA datasets of magnoliids and other basal angiosperms, including Aristolochia, Persea, Liriodendron, Nuphar and Amborella [5]. The Monocot Tree of Life project [42] is generating deep transcriptome datasets for at least 50 monocot species that previously have not been the focus of genome-scale sequencing. The 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project [43] is generating at least 3 Gb of Illumina paired-end RNAseq data from each of 1,000 plant species from green algae through angiosperms (Viridiplantae). In this study, we draw upon these resources, including an initial collection of basal eudicot species that have been very deeply sequenced by the 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project. Six members of Papaveraceae (Argemone mexicana, Eschscholzia californica, and four species of Papaver) have been targeted for especially deep sequencing, with over 12 Gb of cDNA sequence derived from four or five tissue-specific RNAseq libraries. Three other basal eudicots (Podophyllum peltatum (Berberidaceae), Akebia trifoliata (Lardizabalaceae), and Platanus occidentalis (Platanaceae)) sequenced by the 1000 Green Plant (1KP) Transcriptome Project, and EST sets available for additional strategically placed species (for example, [44,45]) were employed for phylogenomic estimation of the timing of the γ event. Assembled unigenes (sequences produced from assembly of EST data sets) were sorted into gene families and then the phylogenetic analyses of gene families were performed to test alternative hypotheses for the phylogenetic placement of the γ event.

Results and discussion

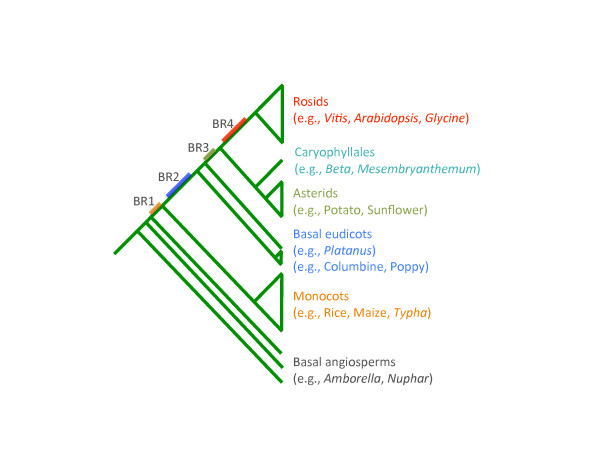

Since the γ event was first identified in a groundbreaking phylogenomic analysis of the Arabidopsis genome [9], its timing has been hypothesized to have predated the origin of angiosperms (for example, [25,46]), the divergence of monocots and eudicots (for example, [47]) and the divergence of asterid and rosid eudicot clades (for example, [11,35]) (Figure 1). Most recent analyses suggest that γ occurred within the eudicots, but the timing of the γ event relative to the diversification of core eudicots remains unclear [13]. Resolving whether γ occurred just before the radiation of core eudicots or earlier, in a common ancestor of all eudicots, has implications for our understanding of the relationship between polyploidization, diversification rates, and morphological novelty (for example, [14]).

Figure 1.

Schematic phylogenetic tree of flowering plants. BR1 to BR4 denote potential time points when the γ event may have occurred. BR1, monocots + eudicots duplication; BR2, eudicot-wide duplication; BR3, core eudicot-wide duplication; BR4, rosid-wide duplication.

Phylogenomic placement of the γ polyploidy event

To ascertain the timing of the γ event relative to the origin and early diversification of eudicots, we mainly focused on dating paralogous gene pairs that are retained on synteny blocks in Vitis [11,12]. Vitis displays the most complete retention for γ blocks among all genomes sequenced to date, and thus provides the best target for phylogenomic mining of the γ history. Vitis also represents the sister group to all other members of the rosid lineage (APG III, 2009) [48,49], so homologous genes were sampled from other species of rosids, asterids, basal eudicots, monocots, and basal angiosperms in order to estimate the timing of the γ event in relation to the divergence of these lineages. Genes were clustered into 'orthogroups' (homologous genes that derive from a single gene in the common ancestor of the focal taxa) using OrthoMCL [50] with eight sequenced angiosperm genomes (Table 1). By excluding Vitis pairs that are not included in the same orthogroups, and requiring that orthogroups contained both monocots and non-Vitis eudicots, 900 pairs of Vitis genes were retained from 781 orthogroups. These orthogroups were used in our investigation of the γ duplication event.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets for eight sequenced plant genomes included in this study

| Species | Annotation version | Number of annotated genes |

|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) | TAIR version 9 | 27,379 |

| Carica papaya (papaya) | ASGPB release | 25,536 |

| Cucumis sativus (cucumber) | BGI release | 21,635 |

| Populus trichocarpa (black cottonwood) | JGI version 2.0 | 41,377 |

| Glycine max (soybean) | Phytozome version 1.0 | 55,787 |

| Vitis vinifera (grape vine) | Genoscope release | 30,434 |

| Oryza sativa (rice) | RGAP release 6.1 | 56,979 |

| Sorghum bicolor | JGI version 1.4 | 34,496 |

These eight genome sequences were used to construct orthogroups, which were then populated with additional unigenes of asterids, basal eudicots, non-grass monocots, and basal angiosperms. The number of annotated genes in each genome is indicated. ASGPB, Advanced Studies of Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics; JGI, Joint Genome Institute; RGAP, Rice Genome Annotation Project; TAIR, The Arabidopsis Information Resource.

To verify that the phylogenetic placement of the γ event was shared by rosids and asterids, and to test whether it was shared by all eudicots or by eudicots and monocots (near angiosperm-wide), these orthogroups were then populated with unigenes of asterids, basal eudicots, non-grass monocots, and basal angiosperms (Table 2). Grasses are known to be distinct from other angiosperms in their high rate of nucleotide substitutions, and codon biases within the grasses make this clade distinct from other angiosperms, including non-grass monocots (for example, [51,52]), so inclusion of non-grass monocots was necessary to reduce artifacts in gene tree estimation. More generally, when dealing with phylogenomic-scale datasets, we strive for adequate taxon sampling to cut long branches, but avoid adding a large proportion of unigenes with low coverage. Inadequate taxon sampling could lead to spurious inference of phylogeny, while incomplete sequences (that is, low-coverage unigenes) can greatly degrade branch support and resolution of phylogenetic trees.

Table 2.

Summary of unigene sequences of asterids, basal eudicots, non-grass monocots, and basal angiosperms included in phylogenetic study

| Species | Lineage | Source | Number of reads/ESTs | Size of data | Assembly method(s) | Number of unigenes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panax quinquefolius | Asterid | NCBI-SRA | 209,745 | 89.7 Mb | MIRA | 22,881 |

| Lindenbergia phillipensis | Asterid | PPGP | 69,545,362 | 5.9 Gb | CLC | 104,904 |

| Helianthus annuus | Asterid | TIGR PTA | 93,279 | NA | Megablast-CAP3 | 44,662 |

| Solanum tuberosum | Asterid | TIGR PTA | 219,485 | NA | Megablast-CAP3 | 81,072 |

| Mimulus gutatus | Asterid | PlantGDB | 231,012 | NA | Vmatch-PaCE-CAP3 | 39,577 |

| Papaver somniferum | Basal eudicot | 1KP + SRA | 140,604,904 + 3,709,876 | 10.3 Gb + 1.3 Gb | MIRA-SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 252,894 |

| Papaver setigerum | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 134,478,938 | 9.8 Gb | SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 406,167 |

| Papaver rhoeas | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 157,506,374 | 11.5 Gb | SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 383,426 |

| Papaver bracteatum | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 89,663,900 | 6.5 Gb | SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 201,564 |

| Eschscholzia californica | Basal eudicot | NCBI + SRA + 1KP | 14,381 + 559,470 + 133,422,402 | 6.8 Mb + 55 Mb + 9.7 Gb | MIRA-SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 165,260 |

| Argemone mexicana | Basal eudicot | 1KP + NCBI | 144,520,360 + 1,692 | 10.5 Gb + 1 Mb | SOAPDenovo- CAP3 | 148,533 |

| Akebia trifoliata | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 29,156,514 | 2.1 Gb | CLC-CAP3 | 46,024 |

| Podophyllum pelatum | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 20,139,210 | 1.5 Gb | CLC-CAP3 | 31,472 |

| Platanus occidentalis | Basal eudicot | 1KP | 25,508,642 | 1.9 Gb | CLC-CAP3 | 42,373 |

| Aquilegia formosa x Aquilegia pubescens | Basal eudicot | PlantGDB | 85,040 | NA | Vmatch-PaCE-CAP3 | 19,615 |

| Mesembryanthemum crystallinum | Caryophillid | PlantGDB | 27,553 | NA | Vmatch-PaCE-CAP3 | 11,317 |

| Beta vulgaris | Caryophillid | PlantGDB | 25,883 | NA | Vmatch-PaCE-CAP3 | 18,009 |

| Acorus americanus | Monocot | MonATOL + 1KP | 149,320 + 15,427,316 | 44.9 Mb + 1.1 Gb | MIRA-SOAPDenovo-CAP3 | 59,453 |

| Chamaedorea seifrizii | Monocot | MonATOL | 33,100,948 | 2.5 Gb | CLC | 68,489 |

| Chlorophytum rhizopendulum | Monocot | MonATOL | 59,505,714 | 4.5 Gb | CLC | 58,766 |

| Neoregelia sp. | Monocot | MonATOL | 49,121,506 | 3.7 Gb | CLC | 63,269 |

| Typha angustifolia | Monocot | MonATOL | 70,733,124 | 5.7 Gb | CLC | 57,980 |

| Persea americana (avocado) | Magnoliid | AAGP | 2,336,819 | 683 Mb | MIRA | 132,532 |

| Aristolochia fimbriata (Dutchman's pipe) | Magnoliid | AAGP | 3,930,505 | 880 Mb | MIRA | 155,371 |

| Liriodendron tulipifera (yellow-poplar) | Magnoliid | AAGP | 2,327,654 | 543 Mb | MIRA | 137,923 |

| Nuphar advena (yellow pond lily) | Basal angiosperm | AAGP | 3,889,719 | 1.1 Gb | MIRA | 289,773 |

| Amborella trichopoda | Basal angiosperm | AAGP | 2,943,273 | 776 Mb | MIRA | 208394 |

1KP, 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project; AAGP, Ancestral Angiosperm Genome Project [44]; MonATOL, Monocot Tree of Life Project [42]; NA, not available; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; PPGP, Parasitic Plant Genome Project [65]; SRA, Sequence Read Archive; TIGR PTA, The Institute for Genomic Research Plant Transcript Assemblies [66].

To phylogenetically place the γ event with confidence, we adopted the following support-based approach. Three relevant bootstrap values were taken into account when evaluating support for a particular duplication. For example, given a topology of (((clade2)bootstrap2,(clade3)bootstrap3)bootstrap1), bootstrap2 and bootstrap3 are the bootstrap values supporting clade2 (clade2 here will include one of the Vitis γ duplicates) and clade3 (including the other Vitis duplicate), respectively, while bootstrap1 is the bootstrap value supporting the larger clade including clade2 and clade3. The value of bootstrap1 indicates the degree of confidence in the inferred ancestral node joining clades 2 and 3. In this study, when bootstrap1, and at least one of bootstrap2 and bootstrap3 were ≥50% (or 80%), we determined whether an asterid, basal eudicot, monocot, or basal angiosperm was contained in clades 2 or 3 (for example, asterids in Figures 2 and 3) or sister to their common ancestor (node defining clade 1) with a bootstrap value (BS) ≥50% (or 80%; for example, basal eudicots, monocots and basal angiosperms in Figures 2 and 3).

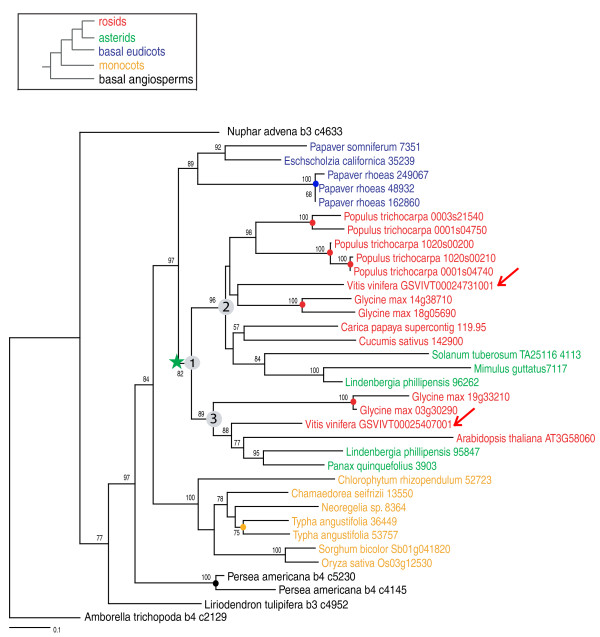

Figure 2.

Exemplar maximum likelihood phylogeny of Ortho 1202. RAxML topology of an orthogroup (Ortho 1202) indicating that the γ paralogs of Vitis were duplicated before the split of rosids and asterids and after the early radiation of eudicots. The scored bootstrap (BS) value for this duplication is over 80%, because nodes #1 and #2 (and/or #3) have BS > 80%. Legend: green star = core eudicot duplication; colored circles = recent independent duplications; numbers = bootstrap support values.

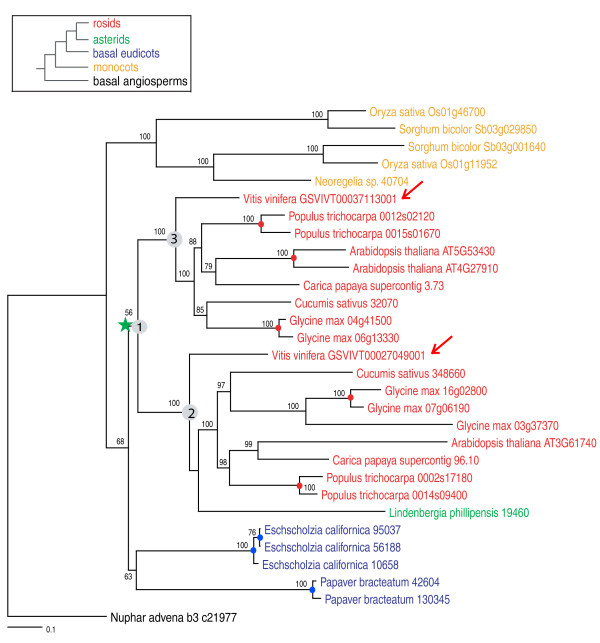

Figure 3.

Exemplar maximum likelihood phylogeny of Ortho 1083. RAxML topology of an orthogroup (Ortho 1083) indicates that the γ paralogs of Vitis were duplicated before the split of rosids and asterids, and after the early radiation of eudicots. The scored bootstrap (BS) value for this duplication is over 50%, because nodes #1 has BS < 80%. Legend: green star = core eudicot duplication; colored circles = recent independent duplications; numbers = bootstrap support values.

Homologous sequences were identified for 769 of the 781 orthogroups and were subsequently used for phylogenetic analysis. For example, orthogroup 1202 was well populated with unigenes of asterids, basal eudicots, non-grass monocots, and basal angiosperms (Figure 2). Two Vitis genes, which were located on a syntenic block, were clustered into two clades, both of which include genes from asterids and other rosids. This phylogenetic tree supports (BS ≥80%) the duplication of two Vitis genes before the split of rosids and asterids and after the divergence of basal eudicots, indicating that γ is restricted to core eudicots (BR3 of Figure 1; Figure 2). In another example, only one asterid unigene passed the quality control steps and was clustered into orthogroup 1083. This asterid unigene was grouped into one of the duplicated clades, also supporting (BS ≥50%) a duplication in the common ancestor of extant core eudicots (BR3 of Figure 1; Figure 3). Only a few duplications of Vitis gene pairs were identified as occurring before the divergence of monocots and eudicots (BR1 of Figure 1; seven duplications with BS ≥50%), or restricted to rosids (BR4 of Figure 1; six duplications with BS ≥50%, four duplications with BS ≥80%). We identified 168 Vitis gene pairs that were duplicated after the split of basal eudicots (BR3 of Figure 1) with BS ≥50%, and 80 of these had BS ≥80%. We also found that 70 Vitis genes were duplicated before the separation of basal eudicots (BR2 of Figure 1) with BS ≥50% and 19 with BS ≥80% (Table 3). Therefore, our phylogenomic analysis provided very strong support that γ occurred before the divergence of rosids and asterids, after the split of monocots and eudicots, and most likely after the earliest diversification of eudicots.

Table 3.

Phylogenetic timing of Vitis γ duplications inferred from orthogroup phylogenetic histories

| BR1 | BR2 | BR3 | BR4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ortho | BS ≥ 80 | BS ≥ 50 | BS ≥ 80 | BS ≥ 50 | BS ≥ 80 | BS ≥ 50 | BS ≥ 80 | BS ≥ 50 |

| Duplications | 0 | 7 | 19 | 70 | 80 | 168 | 4 | 6 |

| Percent | 0% | 2.8% | 18.3% | 27.9% | 77.7% | 67% | 4% | 2.3% |

BRx designations are illustrated in Figure 1. Bootstrap (BS) ≥80 and BS ≥50 are counts of nodes resolved with BS ≥80 or ≥50, respectively.

Molecular dating of the γ duplications

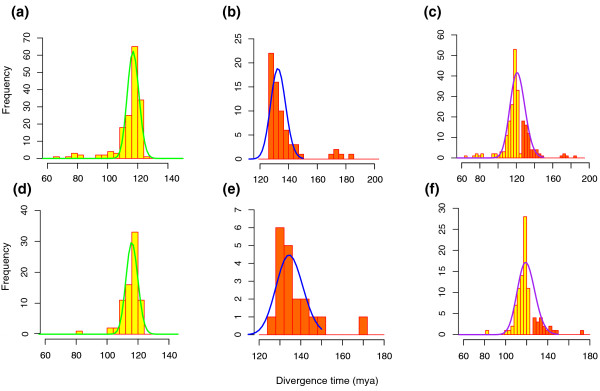

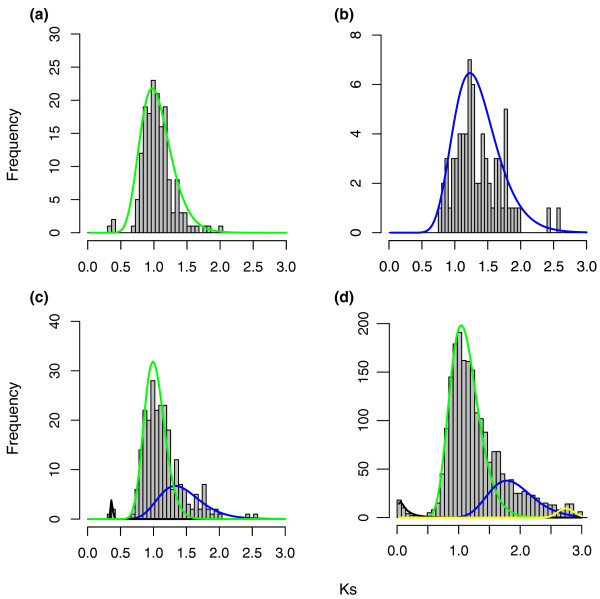

To estimate the absolute date of the γ event, we calibrated 161 of the 168 orthogroups supporting (BS ≥50%) a core eudicot-wide duplication and 66 of the 70 orthogroups supporting a eudicot-wide duplication, and then estimated the duplication times using the program r8s [53] (Materials and methods). We then analyzed the distribution of the inferred duplication times using a Bayesian method that assigned divergence time estimates to classes specified by a mixture model [54]. The distribution of duplication times of core eudicot-wide Vitis pairs shows a peak at 117 ± 1 (95% confidence interval) (Figure 4a), and the distribution of all eudicot-wide duplication times has a peak at 133 ± 1 million years ago (mya) (Figure 4b). Dating estimates have additional sources of error beyond the sampling effects accounted for in standard error estimates (for example, [55]). However, the clear pattern is that the duplication branch points occurred over a narrow window of time very close to the eudicot calibration point that represents the first documented appearance of tricolpate pollen in the fossil record. We also analyzed the 80 nodes and 19 nodes showing duplication shared by core eudicots and all eudicots, respectively, with bootstrap support ≥80% (Figure 4d, e) and found similar distributions (116 ± 1 mya for core eudicot duplications and 135 ± 2 mya for all eudicot duplications). The inferred dates for Vitis duplications shared either by core eudicots or all eudicots are very close to each other, and are concentrated around 125 mya. We also investigated the distribution of all inferred duplication times together (core eudicot-wide and eudicot-wide). Even given a time constraint (125 mya) that would split the date estimates for core eudicot and eudicot-wide duplications, the distributions of combined inferred duplication times show only one significant peak, with a mean at 121 mya for orthogroups with bootstrap support ≥50% (Figure 4c) and 120 mya for orthogroups with bootstrap support ≥80% (Figure 4f). A single peak observed for the combined data (Figure 4c) suggests that the genome-scale event(s) leading to the triplicated genome structure of core eudicots occurred in a narrow window of time nearly coincident with the sudden appearance of eudicot pollen-types in the fossil record [56].

Figure 4.

Age distribution of γ duplications. (a) The inferred duplication times for 161 γ duplication nodes that support core eudicot-wide duplication (BS ≥50%) were analyzed by EMMIX to determine whether these duplications occurred randomly over time or within some small timeframe. Each component is written as 'color/mean molecular timing/proportion' where 'color' is the component (curve) color and 'proportion' is the percentage of duplication nodes assigned to the identified component. There is one statistically significant component: green/117 (mya)/1. (b) Distribution of inferred γ duplication times from 66 orthogroups that support a eudicot-wide duplication with BS ≥50%. There is one statistically significant component: blue/133 (mya)/1. (c) Distribution of inferred γ duplication times from combination of (a) and (b) shows one significant component: purple/121 (mya)/1. (d-f) Corresponding distributions of inferred duplication times from orthogroups with BS ≥80%. One significant component in (d), green/116 (mya)/1; one in (e), blue/135 (mya)/1; and one in (f), purple/120 (mya)/1.

Hexaploidization and early eudicot radiation are close in time

Many of the gene trees showed no resolution or low bootstrap support for nodes distinguishing hypotheses BR2 and BR3. If the γ event had occurred almost anywhere along the long branch leading to eudicots, this event would have been relatively easy to resolve. The lack of resolution of the timing of duplication events around the basal eudicot speciation nodes suggests that the γ event may have occurred during a rapid species radiation. Another possibility could be due to the nature of hexaploidization. If, as our analyses suggest, the polyploidy event (see below for possible scenarios) occurred soon after the divergence of basal eudicots, the substitution rates for γ paralogs could vary. For example, one duplicate could evolve very slowly while the other evolves at an accelerated rate [4]. These possibilities could add significant challenges to the precise resolution of events occurring at or near the branch points for basal versus core eudicot lineages. Despite these challenges, most well-resolved gene trees support the hypothesis that the γ event occurred in association with the origin and diversification of the core eudicots, after the core eudicot lineage diverged from the Ranunculales (BR3 of Figure 1).

Nature of the γ event

An additional question is whether the ancient hexaploid common ancestor was formed by one or two WGDs that occurred over a very short period (for example, as with hexaploid wheat). It was demonstrated that two of the three homologous regions were more fractionated than the third, suggesting a possible mechanism for the γ event [34]. In one proposed scenario, a genome duplication event generated a tetraploid, which then hybridized with a diploid to generate a (probably sterile) triploid. Finally, a second WGD event doubled the triploid genome to generate a fertile hexaploid. Alternatively, unreduced gametes of a tetraploid and a diploid could have fused to generate a hexaploid directly. Another characterization of syntenic blocks indicates that the three corresponding regions are generally equidistant from one another [11]. Our analyses of duplication points in the phylogenomic analyses resolve only a single peak in estimated dates for the 'γ event', which would be consistent with either scenario, given that any complex scenario would involve ancient events that occurred within a brief period of time. More evidence is needed to establish a more definitive mechanism for the apparent hexaploidization (that is, as one versus two events, allopolyploid versus autopolyploid).

Rate variations between paralogs of Vitis

In another attempt to increase resolving power, Ks distributions for duplicate Vitis genes were investigated. The Ks distributions of Vitis pairs supporting a core eudicot-wide duplication inferred from phylogenetic analyses show one significant peak at Ks ~1.03 (Figure 5a). The Ks values for eudicot-wide duplicate Vitis pairs were not well clustered, and their distribution shows one peak at 1.31, which indicates slightly more divergence for these Vitis pairs (Figure 5b). This result is consistent with phylogenetic analyses that show this set of duplications occurred somewhat earlier (all eudicot-wide versus core eudicot-wide). We also investigated the distribution of all Ks values together (core eudicot-wide and eudicot-wide). Three statistically significant peaks were identified: 0.3, 1.02 and 1.40 (Figure 5c). Finally, we estimated Ks values for all (2,191) pairs of Vitis γ paralogs identified by Tang et al. [11] in analyses of syntenic blocks. We were able to detect four significant components using the mixture model implemented with EMMIX (McLachlan et al. [54]): 0.12, 1.09, 1.85, and 2.7 (Figure 5d). This Ks distribution clearly shows that the major peak (approximately 1.09; green curve in Figure 5d) was close to the peak of Ks distribution of core eudicot-wide duplicates (at approximately 1.03; Figure 5a). This intriguing pattern (Figure 5c, d) could be a consequence of stable hexaploidy arising from two WGDs, one in the common ancestor of all eudicots and one in the common ancestor of core eudicots. However, there are no consistent patterns of duplications for entire syntenic blocks; for example, some syntenic blocks have genes consistently duplicated in core eudicots, while other syntenic blocks were duplicated eudicot-wide (results not shown). Alternatively, this pattern also could be consistent with the hypothesis of an allopolyploidy event for γ. If two ancestral genomes were involved in the hexaploidization and the Vitis genome had evolved slowly, two significant peaks might be detected [57]. A third possibility is that Vitis pairs supporting a eudicot-wide duplication may be the products of pre-WGD tandem or segmental duplications that were misidentified as syntenic γ paralogs due to loss of alternative copies through the fractionation process. These hypotheses will have to be tested through comparative analyses as additional plant genomes, especially of outgroups (for example, Aquilegia, Amborella) and other basal eudicots (eg., Buxus, Trochodendron), are sequenced.

Figure 5.

Ks distributions of paralogs in Vitis from syntenic block analysis. Methods for sequence alignment and estimation of Ks were as reported (Cui et al. 2006), but were here limited to paralogous gene pairs retained on syntenic blocks in the Vitis genome. Colored lines superimposed on Ks distribution represent significant duplication components identified by likelihood mixture model as in Figure 4 (Materials and methods). a, Ks distribution of 168 Vitis pairs supporting core eudicot-wide duplication in phylogenetic analysis. One statistically significant component: green/1.03/1. b, Ks distribution of 70 Vitis pairs showing all eudicot-wide duplications on phylogenies. One significant component: blue/1.31/1. c, Ks distribution of combination of Vitis pairs supporting core eudicot- (a) and eudicot-wide duplications (b) on phylogenies. Three significant components: black/0.3/0.01, green/1.02/0.70, blue/1.40/0.29. d, Ks distribution of 2191 paralogous pairs were identified from syntenic block analysis. Four significant components: black/0.12/0.02, green/1.09/0.74, blue/1.85/0.22, yellow/2.7/0.02.

Implications of the γ event characterizing most eudicots

Our results suggest that the γ polyploidy event was closely coincident with a rapid radiation of major lineages of core eudicot lineages that together contain about 75% of living angiosperm species. This rapid lineage expansion following the γ event could be an important exception to the general pattern described by Mayrose et al. [31], who concluded that there may generally be reduced survival of polyploid plant lineages. The eudicots consist of a graded series of generally small clades (often called early-diverging or basal eudicots) that are successive sisters to the core eudicots ([49] and references therein). It is within the core eudicot clade where most major lineages as well as the large majority of angiosperm species reside (for example, rosids, asterids, caryophyllids). Several key evolutionary events seem to correspond closely to the origin of the core eudicots, including the genome-wide event described here, the evolution of a pentamerous, highly synorganized flower with a well-differentiated perianth, and the production of ellagic and gallic acids [58]. Significantly, the duplication of several genes crucial to the establishment of floral organ identity also occurred near the origin of the core eudicots (AP3, AP1, AG, and SEP gene lineages) [46,59,60], suggesting that these duplications - possibly originating from the γ event - may also be involved in the 'new' floral morphology that emerged in this clade [61,62].

This study also helps to shed light on prior studies, where the potential timing of the γ event varied widely from possibly in an ancestor of all angiosperms [9] to perhaps as recent as only rosids [63]. A polyploid event has been detected that is angiosperm-wide, but this was an earlier event (ε, epsilon) [5]. Our results are consistent with a recent study that identified a signature of the γ event in the genome of the potato, an asterid [35]. The γ event was suggested to be absent from grass genomes in comparisons of Vitis and Oryza [32], but this finding was questioned by Tang et al. [11]. However, the draft genome of strawberry (Fragaria vesca), a rosid that shares the γ event, did not show evidence for γ in syntenic block analysis [64], suggesting that either the γ event has been obscured by further rearrangements and fractionation, or expansion of the Fragaria genome sequence data may be necessary. Although sequenced plant genomes are being produced at an increasing rate, a much larger source of genome-scale evidence is coming from very large-scale transcriptome studies such as the 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project and the Monocot Tree of Life Project. In this paper, we have used gigabases of transcriptome data from species at key branch points to phylogenetically time hundreds of ancient gene duplications. Combined with evidence from Ks analysis and syntenic blocks, global gene family phylogenies could incorporate extensive evidence without a sequenced genome, and ultimately facilitate a much better understanding of plant evolution.

Conclusions

Phylogenetic analyses and molecular dating provide consistent and strong evidence supporting the occurrence of the γ polyploidy event after the divergence of monocots and eudicots, and before the asterid-rosid split. It is difficult to determine whether the γ event was shared by monocots or not based only on synteny patterns shared between Vitis and other monocot genomes [11]. By including massive transcriptome datasets from many additional taxa, such as basal angiosperms, non-grass monocots, basal eudicots and asterids, we employed a comprehensive phylogenomic approach, and dated gene pairs on syntenic blocks in a relatively slowly evolving species (Vitis) [11]. We were able to place the γ event(s) in a narrow window of time, most likely shortly before the origin and rapid radiation of core eudicots.

Material and methods

Data and assemblies

Genomes were obtained from various sources as given in Table 1. EST data or assemblies were obtained from sources indicated in Table 2. The largest quantities of new sequence data are represented by transcriptome datasets for nine basal eudicot species produced by Beijing Genomics Institute for the 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project [43]. The Monocot Tree of Life Project (MonATOL) generated five non-grass monocot transcriptomes. One transcriptome dataset for Lindenbergia philippensis (asterid) was obtained from the Parasitic Plant Genome Project [65]. Several methods were used for EST data assembly, according to the type and quantity of data that were available. Assemblies involving large numbers of Sanger reads were obtained either from the Plant Genome Database [45] or The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) Plant Transcript Assemblies [66]. Hybrid assemblies with Sanger and 454 data were performed with MIRA.Est. Short-read Illumina datasets were assembled either with SOAP denovo (K-mer size = 29 and asm_flag = 2) [67] or with CLC Genomics Workbench (reads trimmed first, and using default parameters except minimum contig length set to 200 bases). Assemblies for species with data from more than one sequencing technology were further post-assembled with CAP3 (overlap length cutoff = 40 and overlap percent identity = 98) to merge contigs that have significant overlap but could not be assembled into contiguous sequences by primary assemblers due to either the presence of SNPs in the consensus or path ambiguity in the graph.

Gene classification and phylogenetic analysis

The OrthoMCL method [50] was used to construct sets of orthogroups. Amino acid alignments for each orthogroup were generated with MUSCLE, and then trimmed by removing poorly aligned regions with trimAl 1.2, using the heuristic automate1 option [68]. In order to sort and align transcriptome data into our eight-genome scaffold for downstream phylogenetic analyses, we first used ESTScan [69] to find the best reading frame for all unigenes. The best hit from a blast search against the inferred proteins of our eight-genome scaffold was then used to assign each unigene to an orthogroup. Additional sorted unigene sequences for the orthogroups of sequenced genomes were aligned at the amino acid level into the existing full alignments (before trimming) of eight sequenced species using ClustalX 1.8 [70]. Then these large alignments were trimmed again using trimAl 1.2 with the same settings. Each unigene sequence was checked and removed from the alignment if the sequence contained less than 70% of the total alignment length. Corresponding DNA sequences were then forced onto the amino acid alignments using custom Perl scripts, and DNA alignments were used in subsequent phylogenetic analysis. Maximum likelihood analyses were conducted using RAxML version 7.2.1 [71], searching for the best maximum likelihood tree with the GTRGAMMA model by conducting 100 bootstrap replicates, which represents an acceptable trade-off between speed and accuracy (RAxML 7.0.4 manual).

Molecular dating analyses and 95% confidence intervals

The best maximum-likelihood topology for each orthogroup was used to estimate divergence times. The divergence time of the two paralogous clades in each orthogroup was estimated under the assumption of a relaxed molecular clock by applying a semi-parametric penalized likelihood approach using a truncated Newton optimization algorithm as implemented in the program R8S [53]. The smoothing parameter was determined by cross-validation. We used the following dates in our estimation procedure: minimum age of 131 mya [72] and maximum age of 309 mya for crown-group angiosperms [73], and a fixed constraint age of 125 mya for crown-group eudicots [56]. We required that trees pass both the cross-validation procedure and provide estimates of the age of the duplication node. The collection of inferred divergence times was then analyzed by EMMIX [54]. For each significant component identified by EMMIX, the 95% confidence interval of the mean was then calculated.

Finite mixture models of genome duplications

To explore the divergence patterns for duplicated genes, the inferred distribution of Ks divergences were fitted to a mixture model comprising several component distributions in various proportions. The Ks value for each duplicated sequence pair was calculated using the Goldman and Yang maximum likelihood method implemented in codeml with the F3X4 model [74]. The EMMIX software was used to fit a mixture model of multivariate normal components to a given data set. The mixed populations were modelled with one to four components. The EM algorithm was repeated 100 times with random starting values, as well as 10 times with k-mean starting values. The best mixture model was identified using the Bayesian information criterion.

Abbreviations

BS: bootstrap value; EST: expressed sequence tag; Ks: rate of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site; mya: million years ago; WGD: whole genome duplication.

Authors' contributions

YJ, JL-M and CWD conceived of the study and its design, and YJ performed all of the final analyses. YJ, JL-M, CWD drafted the primary manuscript and additional text and discussion of the research was provided by DES, PSS, JEB, NJW, TMK, GW, DWS. Tissue samples, RNA isolations, library preparation sequencing and sample and sequence management were done by MR, MRM, JM, MR, XW, YongZ, JW, ASC, MKD, RM and JCP. Data assemblies and other analyses were done by YJ, SA, DRR, EW, and YetingZ. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Yuannian Jiao, Email: yxj129@psu.edu.

Jim Leebens-Mack, Email: jleebensmack@plantbio.uga.edu.

Saravanaraj Ayyampalayam, Email: raj@plantbio.uga.edu.

John E Bowers, Email: jebowers@uga.edu.

Michael R McKain, Email: mrmckain@gmail.com.

Joel McNeal, Email: jmcneal@plantbio.uga.edu.

Megan Rolf, Email: mrolf@danforthcenter.org.

Daniel R Ruzicka, Email: druzicka@danforthcenter.org.

Eric Wafula, Email: ekw10@psu.edu.

Norman J Wickett, Email: nwickett@chicagobotanic.org.

Xiaolei Wu, Email: wuxiaolei@genomics.org.cn.

Yong Zhang, Email: zhangy@genomics.org.cn.

Jun Wang, Email: wangj@genomics.org.cn.

Yeting Zhang, Email: yzz119@psu.edu.

Eric J Carpenter, Email: ejc@ualberta.ca.

Michael K Deyholos, Email: deyholos@ualberta.ca.

Toni M Kutchan, Email: tmkutchan@danforthcenter.org.

Andre S Chanderbali, Email: achander@ufl.edu.

Pamela S Soltis, Email: psoltis@flmnh.ufl.edu.

Dennis W Stevenson, Email: dws@nybg.org.

Richard McCombie, Email: mccombie@cshl.edu.

J Chris Pires, Email: piresjc@missouri.edu.

Gane Ka-Shu Wong, Email: gane@ualberta.ca.

Douglas E Soltis, Email: dsoltis@botany.ufl.edu.

Claude W dePamphilis, Email: cwd3@psu.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joshua P Der for helpful comments. This work was supported in part by funds from the NSF Plant Genome Research Program (DEB 0638595, The Ancestral Angiosperm Genome Project to CWD, JL-M, PSS, DES; DEB 0701748, The Parasitic Plant Genome Project to CWD; DEB 0922742, The Amborella Genome: A Reference for Plant Biology to CWD, JL-M, PSS, DES; IOS 0421604, Genomics of Comparative Seed Evolution to DWS, RM), NSF Tree of Life program ('MonATOL,' DEB 0829868, From Acorus to Zingiber - Assembling the Phylogeny of the Monocots to DWS, JCP, JL-M, RM, CWD), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health (project 5R01DA025197-02 to TMK, CWD, JL-M), the Alberta 1000 Plants Initiative (1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project, to GW) by Alberta Advanced Education and Technology, by Musea Ventures, and by BGI-Shenzhen), iPLant (to JL-M) and by the Biology Department and Plant Biology Graduate Program of Penn State University.

References

- Ohno S. Evolution by Gene Duplication. Springer-Verlag; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aury JM, Jaillon O, Duret L, Noel B, Jubin C, Porcel BM, Segurens B, Daubin V, Anthouard V, Aiach N, Arnaiz O, Billaut A, Beisson J, Blanc I, Bouhouche K, Camara F, Duharcourt S, Guigo R, Gogendeau D, Katinka M, Keller AM, Kissmehl R, Klotz C, Koll F, Le Mouel A, Lepere G, Malinsky S, Nowacki M, Nowak JK, Plattner H. et al. Global trends of whole-genome duplications revealed by the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia. Nature. 2006;444:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature05230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Clifton SW, Schlarbaum SE, Schuster SC, Ma H, Leebens-Mack J, dePamphilis CW. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011;473:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature09916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Hokamp K, Wolfe KH. A recent polyploidy superimposed on older large-scale duplications in the Arabidopsis genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:137–144. doi: 10.1101/gr.751803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming R, Hou S, Feng Y, Yu Q, Dionne-Laporte A, Saw JH, Senin P, Wang W, Ly BV, Lewis KL, Salzberg SL, Feng L, Jones MR, Skelton RL, Murray JE, Chen C, Qian W, Shen J, Du P, Eustice M, Tong E, Tang H, Lyons E, Paull RE, Michael TP, Wall K, Rice DW, Albert H, Wang ML, Zhu YJ. et al. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus). Nature. 2008;452:991–996. doi: 10.1038/nature06856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision TJ, Brown DG, Tanksley SD. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science. 2000;290:2114–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JE, Chapman BA, Rong J, Paterson AH. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature. 2003;422:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nature01521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JA, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Plants with double genomes might have had a better chance to survive the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5737–5742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900906106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Wang X, Bowers JE, Ming R, Alam M, Paterson AH. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 2008;18:1944–1954. doi: 10.1101/gr.080978.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Bowers JE, Wang X, Ming R, Alam M, Paterson AH. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science. 2008;320:486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Peer Y. A mystery unveiled. Genome Biol. 2011;12:113. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Albert VA, Leebens-Mack J, Bell CD, Paterson AH, Zheng C, Sankoff D, Depamphilis CW, Wall PK, Soltis PS. Polyploidy and angiosperm diversification. Am J Bot. 2009;96:336–348. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, Bai Y, Mun JH, Bancroft I, Cheng F, Huang S, Li X, Hua W, Freeling M, Pires JC, Paterson AH, Chalhoub B, Wang B, Hayward A, Sharpe AG, Park BS, Weisshaar B, Liu B, Li B, Tong C, Song C, Duran C, Peng C, Geng C, Koh C. et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schranz ME, Mitchell-Olds T. Independent ancient polyploidy events in the sister families Brassicaceae and Cleomaceae. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1152–1165. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P, Boore JL. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels A, Koh EG, Chia JM, Brenner S, Aparicio S, Venkatesh B. Fugu genome analysis provides evidence for a whole-genome duplication early during the evolution of ray-finned fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Brunet F, Petit JL, Stange-Thomann N, Mauceli E, Bouneau L, Fischer C, Ozouf-Costaz C, Bernot A, Nicaud S, Jaffe D, Fisher S, Lutfalla G, Dossat C, Segurens B, Dasilva C, Salanoubat M, Levy M, Boudet N, Castellano S, Anthouard V, Jubin C, Castelli V, Katinka M, Vacherie B, Biemont C, Skalli Z, Cattolico L, Poulain J. et al. Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype. Nature. 2004;431:946–957. doi: 10.1038/nature03025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Wall PK, Leebens-Mack JH, Lindsay BG, Soltis DE, Doyle JJ, Soltis PS, Carlson JE, Arumuganathan K, Barakat A, Albert VA, Ma H, dePamphilis CW. Widespread genome duplications throughout the history of flowering plants. Genome Res. 2006;16:738–749. doi: 10.1101/gr.4825606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JM, Cui L, Wall PK, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Leebens-Mack J, Ma H, Altman N, dePamphilis CW. Expression pattern shifts following duplication indicative of subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization in regulatory genes of Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:469–478. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Thomas MA. The monosaccharide transporter gene family in Arabidopsis and rice: a history of duplications, adaptive evolution, and functional divergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2412–2423. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad B, Antonarakis SE. Gene duplication: a drive for phenotypic diversity and cause of human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:17–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.021307.110233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Van de Peer Y. From 2R to 3R: evidence for a fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD). Bioessays. 2005;27:937–945. doi: 10.1002/bies.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bodt S, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Genome duplication and the origin of angiosperms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Force AG. The origin of interspecific genomic incompatibility via gene duplication. Am Nat. 2000;156:590–605. doi: 10.1086/316992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Scannell DR, Byrne KP, Gordon JL, Wong S. Multiple rounds of speciation associated with reciprocal gene loss in polyploid yeasts. Nature. 2006;440:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature04562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Meyer A. Genome duplication, divergent resolution and speciation. Trends Genet. 2001;17:299–301. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth CR, Windham MD. A model for divergent, allopatric speciation of polyploid pteridophytes resulting from silencing of duplicate-gene expression. Am Nat. 1991;137:515–526. doi: 10.1086/285180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker MS, Vogel H, Schranz ME. Paleopolyploidy in the Brassicales: analyses of the Cleome transcriptome elucidate the history of genome duplications in Arabidopsis and other Brassicales. Genome Biol Evol. 2009;5:391–399. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrose I, Zhan SH, Rothfels CJ, Magnuson-Ford K, Barker MS, Rieseberg LH, Otto SP. Recently formed polyploid plants diversify at lower rates. Science. 2011;333:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1207205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, Choisne N, Aubourg S, Vitulo N, Jubin C, Vezzi A, Legeai F, Hugueney P, Dasilva C, Horner D, Mica E, Jublot D, Poulain J, Bruyere C, Billault A, Segurens B, Gouyvenoux M, Ugarte E, Cattonaro F, Anthouard V, Vico V, Del Fabbro C, Alaux M, Di Gaspero G, Dumas V. et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak J, Luo MC, Yang ZL, Zhang HB. The structure of the Aegilops tauschii genepool and the evolution of hexaploid wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:657–670. doi: 10.1007/s001220050942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons E, Pedersen B, Kane J, Freeling M. The value of nonmodel genomes and an expample using synmap within CoGe to dissect the hexaploidy that predates the rosids. Tropical Plant Biol. 2008;1:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s12042-008-9017-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Pan S, Cheng S, Zhang B, Mu D, Ni P, Zhang G, Yang S, Li R, Wang J, Orjeda G, Guzman F, Torres M, Lozano R, Ponce O, Martinez D, De la Cruz G, Chakrabarti SK, Patil VU, Skryabin KG, Kuznetsov BB, Ravin NV, Kolganova TV, Beletsky AV, Mardanov AV, Di Genova A, Bolser DM, Martin DM, Li G, Yang Y. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature. 2011;475:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccolo A, Bowers JE, Estill JC, Xiong Z, Luo M, Sebastian A, Goicoechea JL, Collura K, Yu Y, Jiao Y, Duarte J, Tang H, Ayyampalayam S, Rounsley S, Kudma D, Paterson AH, Pires JC, Chanderbali A, Soltis DE, Chamala S, Barbazuk B, Soltis PS, Albert VA, Ma H, Mandoli D, Banks J, Carlson JE, Tomkins J, Depamphilis CW, Wing RA. et al. A physical map for the Amborella trichopoda genome sheds light on the evolution of angiosperm genome structure. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R48. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-r48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leebens-Mack J, Raubeson LA, Cui L, Kuehl JV, Fourcade MH, Chumley TW, Boore JL, Jansen RK, depamphilis CW. Identifying the basal angiosperm node in chloroplast genome phylogenies: sampling one's way out of the Felsenstein zone. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1948–1963. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst Zool. 1978;27:401–410. doi: 10.2307/2412923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy MD, Penny D. A framework for the quantitative study of evolutionary trees. Syst Zool. 1989;38:297–309. doi: 10.2307/2992396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Childs KL, Hamilton JP, Zhu W, Ly E, Cheung F, Wu H, Rabinowicz PD, Town CD, Buell CR, Chan AP. The TIGR plant transcript assemblies database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D846–851. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway M, Cochrane G, Sugawara H. Archiving next generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D870–871. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monocot Tree of Life Project. http://www.botany.wisc.edu/givnish/monocotatol.htm

- 1000 Green Plant Transcriptome Project. http://www.onekp.com

- Ancestral Angiosperm Genome Project. http://ancangio.uga.edu

- PlantGDB. http://www.plantgdb.org/

- Zahn LM, Kong H, Leebens-Mack JH, Kim S, Soltis PS, Landherr LL, Soltis DE, Depamphilis CW, Ma H. The evolution of the SEPALLATA subfamily of MADS-box genes: a preangiosperm origin with multiple duplications throughout angiosperm history. Genetics. 2005;169:2209–2223. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BA, Bowers JE, Feltus FA, Paterson AH. Buffering of crucial functions by paleologous duplicated genes may contribute cyclicality to angiosperm genome duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2730–2735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507782103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Brockington SF, Alexandre R, Davis CC, Latvis M, Manchester SR, Soltis DE. Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3853–3858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813376106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Smith SA, Cellinese N, Wurdack KJ, Tank DC, Brockington SF, Refulio-Rodriguez NF, Walker JB, Moore MJ, Carlsward BS, Bell CD, Latvis M, Crawley S, Black C, Diouf D, Xi Z, Rushworth CA, Gitzendanner MA, Sytsma KJ, Qiu YL, Hilu KW, Davis CC, Sanderson MJ, Beaman RS, Olmstead RG, Judd WS, Donoghue MJ, Soltis PS. Angiosperm phylogeny: 17 genes, 640 taxa. Am J Bot. 2011;98:704–730. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl JC, Cheung F, Yuan QP, Martin W, Zewdie Y, McCallum J, Catanach A, Rutherford P, Sink KC, Jenderek M, Prince JP, Town CD, Havey MJ. A unique set of 11,008 onion expressed sequence tags reveals expressed sequence and genomic differences between the monocot orders Asparagales and Poales. Plant Cell. 2004;16:114–125. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl JC, Havey MJ, Martin WJ, Cheung F, Yuan QP, Landherr L, Hu Y, Leebens-Mack J, Town CD, Sink KC. Comparative genomic analyses in Asparagus. Genome. 2005;48:1052–1060. doi: 10.1139/g05-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:301–302. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan GJ, Peel D, Basford KE, Adams P. The Emmix software for the fitting of mixtures of normal and t-components. J Stat Softw. 1999;4:i02. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DA. How to summarize estimates of ancestral divergence times. Evol Bioinform Online. 2008;4:75–95. doi: 10.4137/ebo.s545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA, Hotton CL. Pollen and Spores. Patterns of Diversification. Oxford: Clarendon; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Plant Biologists. Symposium II: Polyploidy, Heterosis, and Genomic Plasticity. http://abstracts.aspb.org/pb2010/public/S02/S022.html

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Endress PK, Chase MW. Phylogeny and Evolution of Angiosperms. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Litt A, Irish VF. Duplication and diversification in the APETALA1/FRUITFULL floral homeotic gene lineage: Implications for the evolution of floral development. Genetics. 2003;165:821–833. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.2.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer EM, Zimmer EA. Gene duplication and floral developmental genetics of basal eudicots. Adv Bot Res. 2006;44:353–384. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Brockington SF, Yoo MJ, Piedrahita A, Latvis M, Moore MJ, Chanderbali AS, Soltis DE. Floral variation and floral genetics in basal angiosperms. Am J Bot. 2009;96:110–128. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanderbali AS, Yoo MJ, Zahn LM, Brockington SF, Wall PK, Gitzendanner MA, Albert VA, Leebens-Mack J, Altman NS, Ma H, Depamphilis CW, Soltis DE, Soltis PS. Conservation and canalization of gene expression during angiosperm diversification accompany the origin and evolution of the flower. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22570–22575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013395108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, Schein J, Sterck L, Aerts A, Bhalerao RR, Bhalerao RP, Blaudez D, Boerjan W, Brun A, Brunner A, Busov V, Campbell M, Carlson J, Chalot M, Chapman J, Chen GL, Cooper D, Coutinho PM, Couturier J, Covert S, Cronk Q. et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science. 2006;313:1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folta KM, Shulaev V, Sargent DJ, Crowhurst RN, Mockler TC, Folkerts O, Delcher AL, Jaiswal P, Mockaitis K, Liston A, Mane SP, Burns P, Davis TM, Slovin JP, Bassil N, Hellens RP, Evans C, Harkins T, Kodira C, Desany B, Crasta OR, Jensen RV, Allan AC, Michael TP, Setubal JC, Celton JM, Rees DJG, Williams KP, Holt SH, Rojas JJR. et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat Genet. 2011;43:109–U151. doi: 10.1038/ng.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasitic Plant Genome Project. http://ppgp.huck.psu.edu

- TIGR Plant Transcript Assemblies database. http://plantta.jcvi.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li R, Zhu H, Ruan J, Qian W, Fang X, Shi Z, Li Y, Li S, Shan G, Kristiansen K, Yang H, Wang J. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20:265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseli C, Jongeneel CV, Bucher P. ESTScan: a program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1999. pp. 138–148. [PubMed]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2002;Chapter 2:Unit 2.3. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes NF, Mcdougall AB. Records of angiospermid pollen entry into the English Early Cretaceous succession. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1987;50:255–272. doi: 10.1016/0034-6667(87)90003-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CN. Implications of fossil conifers for the phylogenetic relationships of living families. Bot Rev. 1999;65:239–277. doi: 10.1007/BF02857631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZH. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]