Transcription, the first step of gene expression, is carried out by DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RNAPs). RNAP catalyzes processive polymerization of RNA messages from NTP precursors by using one strand of DNA as a template. Although the reaction is similar to DNA polymerization (catalyzed by DNA polymerases), important differences exist. First, RNAPs are able to initiate synthesis of RNA from a nucleoside triphosphate, i.e., they do not require oligonucleotide primers. Second, the newly synthesized RNA chain is displaced normally from the DNA template. Thus, during transcription, the DNA strands are separated only in a short region around the catalytic center of the enzyme, the so-called transcription bubble. Because Watson–Crick interactions are required for template-dependent RNA synthesis, a transient RNA⋅DNA hybrid should exist inside the transcription bubble.

After promoter-complex formation, all RNAPs undergo abortive initiation–a catalytic synthesis of short, 2- to 8-nt-long, RNA oligomers that are rapidly synthesized and released from the complex. When the nascent RNA chain reaches a critical length of about 9 bases, it becomes stably associated with the transcription complex. RNAP then clears the promoter and elongates the nascent RNA chain in a fully processive manner. Despite its tight grip on nucleic acids, the elongating RNAP moves rapidly along the DNA and RNA chains until it encounters a termination signal, which typically consists of an RNA hairpin followed by a run of uridines. At such sites, RNAP transiently pauses, the stability of the elongation complex suddenly decreases, and the enzyme releases nucleic acids. The enzyme is now available to initiate transcription from promoters again.

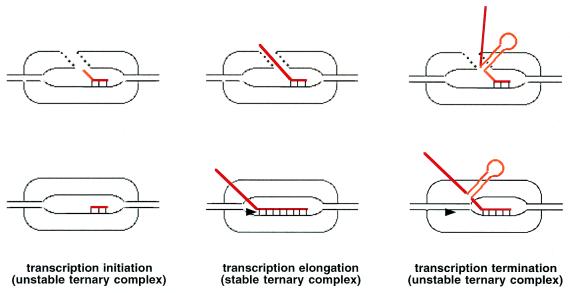

The molecular determinants of transcription-complex stability and processivity are understood poorly. Several competing mechanistic models of RNAP function have been proposed in recent years. Much of the controversy centered around the length of RNA⋅DNA hybrid and its role (or lack thereof) in transcription. If the hybrid were relatively long, say, 8–9 base pairs, then the relative instability of the initial transcribing complex and the complex paused at a terminator could be explained by suboptimal hybrid length (refs. 1 and 2; Fig. 1). Conversely, the establishment of a full-length hybrid could explain the stabilization of the nascent RNA in transcription complex during promoter clearance. In contrast, if the hybrid remains short (less than 3 base pairs) throughout elongation, then complex stability should be determined primarily by the strength of the protein-nucleic acid interactions and/or conformational changes (refs. 2 and 3; Fig. 1). Establishment of the actual length of the hybrid might contribute also to our understanding of mechanisms of action of regulatory factors that modulate the rates of abortive initiation and promoter escape and the efficiency of transcription termination.

Figure 1.

Comparison of short (Upper) and long (Lower) RNA⋅DNA hybrid models of transcription complex. The stabilization of RNA (red) in the ternary transcription results from protein–RNA contacts (Upper) or is caused primarily by the establishment of full-length RNA⋅DNA hybrids (Lower). The crystal structure of transcribing T7 RNAP (12) looks like the schematic structure (Upper Left). Temiakov et al. (15) present data that the elongating T7 RNAP–transcription complex looks like the structure presented (Bottom Center) and, thus, is similar to the Escherichia coli RNAP (7). It is suggested that the structure (Upper Center) may correspond to transcription complex engaged in unproductive reiterative slippage synthesis.

RNAPs seem to have arisen twice in evolution. A large family of multisubunit RNAPs includes bacterial enzymes, archeal enzymes, eukaryotic nuclear RNAPs, plastid-encoded chloroplast RNAPs, and RNAPs from some eukaryotic viruses. Members of this family exhibit extensive sequence and structural similarities (4, 5), suggesting that the mechanism of transcription is conserved highly within this group. The RNAP from E. coli (subunit composition of the catalytic core αIαIIββ′ω, molecular mass ≈380 kDa; it requires the specificity σ subunit to recognize and melt promoter DNA) is the best-studied enzyme of this family. An unrelated family of single-subunit RNAPs includes enzymes from bacteriophages and mitochondria as well as nuclear-encoded RNAPs of chloroplasts. Members of the latter family are related also to DNA polymerases and to reverse transcriptases (6). RNAP from bacteriophage T7 (Mr, ≈100 kDa, does not require additional factors for promoter recognition) is the best-studied member of this family.

Considerable evidence suggests that the hybrid length is ≈8 base pairs during transcription by E. coli RNAP. For example, RNA–DNA crosslinking experiments have established that only 8–9 bases closest to the 3′ end of the nascent RNA remain close to the template DNA strand in active elongation complex (7). Similarly, during initiation, the 5′ end of the nascent RNA remains close to DNA for about 8–9 bases and then branches away (8). Studies of the effects of base-analogue substitutions that either strengthen or weaken Watson–Crick interactions on elongation complex stability and termination efficiency also point to 8- to 9-bp hybrids (7). The upstream portion of the hybrid contributes the most to transcription complex stability (8, 9). Furthermore, a structural model of bacterial RNAP-elongation complex built by superimposing the positions of protein-nucleic acid crosslinks onto a high-resolution structure neatly accommodates an 8-bp hybrid (10).

Despite a lack of sequence similarity between the two RNAP families, the essential elements of the transcription cycle seem to be conserved (11). Thus, if the nucleic acid scaffold plays an essential role in transcription, one would expect that the sizes of the transcription bubble and RNA⋅DNA hybrid would be similar in transcription complexes formed by enzymes of both classes. It was surprising, therefore, when the structure of T7 RNAP complexed with a synthetic promoter and a trinucleotide RNA transcript revealed that only two RNA nucleotides closest to the catalytic center made Watson–crick interactions with the template strand of DNA (12). The 5′-proximal base of RNA appeared to peel away from the template, suggesting that in this system, the hybrid may be as short as 2–3 base pairs. Structural analysis suggested that (i) further extension of the hybrid would result in severe clashes with the T7 RNAP N-terminal domain, and (ii) a surface-exposed channel between the T7 RNAP thumb and the N-terminal domains is positioned appropriately to serve as an exit channel for the displaced RNA. If the difference between the RNA⋅DNA hybrid length in E. coli and T7 RNAP complexes is real, it has important mechanistic implications. For example, although both E. coli and T7 enzymes recognize identical terminators (13, 14), the mechanisms involved must be different (Fig. 1).

Thus, if the nucleic acid scaffold plays an essential role in transcription, one would expect that the sizes of the transcription bubble and RNA⋅DNA hybrid would be similar in transcription complexes formed by enzymes of both classes.

The ultimate way to resolve this impasse is to characterize structurally various intermediates of transcription cycle formed by both types of RNAPs. In the absence of such data, protein–RNA crosslinking and molecular modeling can provide useful information. In a recent issue of PNAS, Temiakov et al. (15) used RNA–DNA and RNA–protein crosslinking to study transcript elongation by T7 RNAP. Temiakov et al. incorporated a crosslinkable analogue of UMP, U*, into defined positions of the nascent RNA of artificially stalled, active T7 RNAP elongation complexes. The flexible spacer arm between the derivatized nucleotide base and the crosslinking group is long enough to allow the crosslinker to reach the complementary strand of a double-stranded nucleic acid. Thus, by following the appearance of RNA–DNA crosslinks between the derivatized nascent RNA and the template DNA strand, one can estimate the length of the RNA⋅DNA hybrid. The results are unambiguous and indicate that RNA–DNA crosslinks persist until the crosslinker is 9 base pairs upstream of the catalytic site (by convention, this position is referred to as −9). When the crosslinker is moved further away from the catalytic center, RNA–DNA crosslinks disappear, and RNA-protein crosslinks become prominent.

The RNA–DNA crosslinking experiment suggests a hybrid that is longer than observed in the structure of initiating T7 RNAP (12). To model the position of the hybrid in an elongating complex, Temiakov et al. (15) mapped the site of a crosslink between a short-range crosslinker incorporated into the nascent RNA 9 base pairs upstream of the catalytic center and RNAP. This critical position, where RNA is displaced from the hybrid, seems to contribute to elongation complex stability. By using a panel of chemical-mapping techniques in combination with RNAP mutants, the crosslink site was localized to within 7 T7 RNAP amino acids in the so-called specificity loop (16). The specificity loop is a phage RNAP-specific feature, which in the open promoter complex recognizes the double-stranded DNA 10–12 base pairs upstream of the transcription initiation start point. Strikingly, 2 amino acids within the 7-aa fragment that harbors the crosslink site are known to contact the promoter at positions −7, −10, and −11 and are critical in specific promoter recognition (16, 17). Thus, it seems that during promoter clearance, the contacts between the specificity loop and the upstream-promoter DNA are broken, and new contacts with RNA and possibly DNA at the upstream edge of the transcription bubble are established. The latter contacts may prevent collapse of the transcription bubble and thus stabilize RNA in the elongation complex. In addition, continued interactions between the specificity loop and DNA during elongation may contribute to sequence-specific pausing by T7 RNAP (18).

Localization of the position of ribonucleotide at the end of the hybrid allowed modeling of the overall position of the hybrid in the elongation complex (the 3′ end of the RNA in the hybrid is constrained, because the position of the catalytic center of the enzyme is known; ref. 16). The proposed trajectory results in few clashes, is consistent with much of the biochemical and genetic data, and is not consistent with the RNA-exit pathway suggested by the structure of the T7 RNAP initiation complex (12). In an independent study, Shen and Kang (19) mapped T7 RNAP–RNA crosslinks from either the derivatized 3′ end of the nascent RNA or from the −9 position of the nascent RNA in several stalled elongation complexes. Their results are in agreement with those of Temiakov et al. (15).

The picture of the T7 RNAP elongation complex that emerges from these studies is remarkably similar to our view of elongation complexes formed by multisubunit RNAPs. The RNA–DNA crosslinking result is superimposable with that obtained by Nudler et al. (7), who used the same experimental approach with E. coli RNAP. Thus, during elongation, the RNA⋅DNA hybrid appears to be 8–9 bp in length in both types of RNAP. In the T7 RNAP elongation complex, the specificity loop is proposed to act as a wedge that both separates the nascent RNA from the DNA template and possibly maintains the upstream edge of the transcription bubble. In the structural model of bacterial RNAP elongation complex (10), an evolutionarily conserved feature of the largest subunit, the so-called “rudder,” seems to play an analogous role. Interestingly, the rudder may also be involved in promoter recognition, because it is close to a region of the specificity subunit σ that recognizes promoter positions −9/−12 (20). Site-directed deletion mutagenesis reveals that the rudder indeed contributes to bacterial RNAP elongation-complex stability by preventing the displacement of the nascent RNA by the nontemplate DNA strand (K. Kuznedelou, N. Korzheva, A. Mustaev, and K.S., unpublished observations). Unfortunately, similar experiments to demonstrate the role of specificity loop in T7 RNAP elongation and complex stability are complicated, because the specificity loop is required strictly for promoter recognition.

The inconsistency between the structure of the T7 RNAP initiation complex obtained by x-ray crystallography and the view that emerges from biochemical studies could be explained by large conformational changes that may occur during the transition from an unstable-initiation complex to a stable-elongation complex. A more likely explanation is that in the crystal structure, T7 RNAP had been captured in an act of unproductive synthesis. When the initial transcribed sequence codes for three Gs in RNA, T7 RNAP can synthesize long chains of poly(G) through repetitive cycles of slippage of the nascent RNA along the template strand and addition of the next GMP (21). During such reiterative synthesis, RNAP does not leave the promoter, and naturally the hybrid can be only 3 bp or less. The addition of the nucleoside triphosphate specified by the fourth position of the template (provided it does not code for a G) inhibits slippage and leads to productive initiation. The crystals of transcribing T7 RNAP complex were obtained in the presence of GTP and chain-terminating α,β-methylene-ATP. Thus, the expected RNA product should have been GGGA. However, the adenosine nucleotide is not present in the structure, and subsequent biochemical data indicate that the ATP analogue has no effect on the slippage reaction (22). Thus, the exit pathway suggested by the early peeling RNA could be that of a slipped transcript and may not be used during productive elongation.

Multisubunit RNAPs also undergo transcript slippage, and the strength of some promoters is regulated by variation of productive vs. unproductive, reiterative initiation events (23). As is the case with T7 RNAP, the slippage reaction in E. coli occurs at the end of a run of three or more identical base pairs in the initial transcribed sequence. Thus, during slippage, the RNA–DNA hybrid is short, suggesting that the RNA-exit pathway of the complex engaged in the slippage synthesis is different from that in the productive complex (10). Interestingly, in bacterial RNAP a surface-exposed channel between the two domains of the second largest subunit exists (4) that is positioned analogously to the putative RNA-exit channel seen on the T7 RNAP transcribing complex (12). Consistent with this idea, in bacterial RNAP, mutations that alter the position of one of the second largest subunit domains or change residues that lie between the two domains result in dramatic changes in the efficiency of reiterative synthesis (24, 25). Future comparative structural analysis of transcription intermediates, in conjunction with biochemical and genetic analyses, should determine the true extent of functional convergence that nature has come up with and solve an identical problem of transcribing a defined fragment of DNA with two different protein machines.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Karen Adelman for her comments. This paper was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 59295.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 14109 in issue 26 of volume 97.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.021535298.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.021535298

References

- 1.Yager T D, von Hippel P H. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1097–1118. doi: 10.1021/bi00218a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nudler E. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:1–12. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uptain S M, Kane C M, Chamberlin M J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:117–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang G, Campbell E A, Minakhin L, Richter C, Severinov K, Darst S A. Cell. 1999;98:811–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer P, Bushnell D A, Fu J, Gnatt A L, Maier-Davis B, Thompson N E, Burgess R R, Edwards A M, David P R, Kornberg R D. Science. 2000;288:640–649. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAllister W T, Raskin C A. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nudler E, Mustaev A, Lukhtanov E, Goldfarb A. Cell. 1997;89:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korzheva N, Mustaev A, Nudler E, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:337–345. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kireeva M L, Komissarova N, Waugh D S, Kashlev M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6530–6536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korzheva N, Mustaev A, Kozlov M, Malhotra A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Darst S A. Science. 2000;289:619–625. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAllister W T. Nuceic Acids Mol Biol. 1997;11:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheetham G M, Steitz T A. Science. 1999;286:2305–2309. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7457–7476. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macdonald L E, Durbin R K, Dunn J J, McAllister W T. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:145–158. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temiakov D, Mentesana P E, Ma K, Mustaev A, Borukhov S, McAllister W T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14109–14114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250473197. . (First Published November 28, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.250473197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheetham G M, Jeruzalmi D, Steitz T A. Nature (London) 1999;399:80–83. doi: 10.1038/19999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raskin C A, Diaz G, Joho K, McAllister W T. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:506–515. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90838-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He B, Kukarin A, Temiakov D, Chin-Bow S T, Lyakhov D, Rong M, Durbin R K, McAllister W T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18802–18811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen, H. & Kang, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Arthur T M, Burgess R R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31381–31387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin, C. T., Muller, D. K. & Coleman, J. E. (1988) 27, 3966–3974. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Imburgio D, Rong M, Ma K, McAllister W T. Biochemistry. 2000;29:10419–10430. doi: 10.1021/bi000365w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Heath L S, Turnbough C L., Jr Genes Dev. 1994;8:2904–2912. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin E, Sagitov V, Burova E, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20175–20180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin D J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11659–11667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]