Abstract

Loss-of-function mutations in CLN3 are responsible for juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL), or Batten disease, which is an incurable lysosomal disease that manifests with vision loss, followed by seizures and progressive neurodegeneration, robbing children of motor skills, speech and cognition, and eventually leading to death in the second or third decade of life. Emerging clinical evidence points to JNCL pathology outside of the CNS, including the cardiovascular system. The CLN3 gene encodes an unusual transmembrane protein, CLN3 or battenin, whose elusive function has been the subject of intense study for more than 10 years. Owing to the detailed characterization of a large number of disease models, our knowledge of CLN3 protein function is finally coming into focus. This review will describe the most current understanding of CLN3 structure, function and dysfunction in JNCL.

Keywords: autophagy, Batten disease, CLN3, endosome, Golgi, juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, lysosome, palmitoylation

Juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis is a lysosomal disease that causes neurodegeneration in children

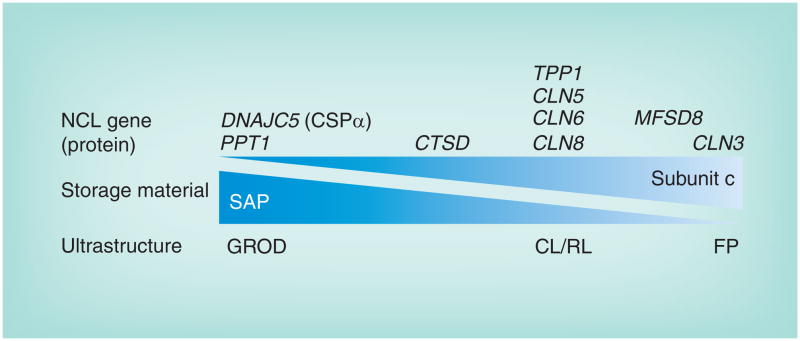

Juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL; MIM #204200) is the most common form of a genetically heterogeneous group of rare disorders known collectively as the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs), or Batten disease. The NCLs, with a combined incidence estimated to be as high as one in 12,500, are inherited neurodegenerative disorders with overlapping symptoms that include seizures, motor and cognitive regression and progressive vision loss leading to complete blindness. The NCLs are named for the ‘ceroid lipofuscin’ lysosomal storage material observed in neurons, although storage is also found in many other cell types, including those outside the CNS. The lysosomal inclusions in the NCLs display one or more characteristic ultrastructural profiles, so-called granular osmiophilic deposits, or curvilinear (CL), rectilinear or fingerprint (FP) profiles, which are diagnostic clues that can direct subsequent genetic testing to identify the causative mutation, typically in one of nine genes (Figure 1). Given the lysosomal storage component of NCL, it is clear that the NCL proteins all directly or indirectly regulate lysosomal function. Several comprehensive reviews and a textbook describing in detail the clinicopathologic features of the NCLs have been published elsewhere [1–4].

Figure 1. The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis disease spectrum.

Lysosomal storage material across the different genetic forms of NCL is heterogeneous and features one or more characteristic ultrastructural profiles. GRODs contain mostly SAPs A and D, and this is the most prominent profile of the storage material when PPT1 is mutated, although sometimes this is mixed with other profiles [16]. On the other end of the spectrum, CLN3 is mostly associated with FP profile storage material, although other profiles may also be present [16]. A number of genes (TPP1, CLN5, CLN6 and CLN8) that are typically linked with NCL onset in the late-infantile years are most associated with CL and RL profiles. CTSD mutations in humans typically cause a rare, severe congenic form of NCL for which there is limited patient information regarding storage material profiles [3]. However, Ctsd deficiency in the mouse leads to both GROD and FP profiles [90]. Finally, GROD storage material was the predominant finding in patients with DNAJC5 mutations. Whether or not there is a relationship between the different ultrastructural profiles of the storage material is unclear.

CL: Curvilinear; FP: Fingerprint; GROD: Granular osmiophilic deposit; NCL: Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis; RL: Rectilinear; SAP: Saposin.

Classical JNCL, caused by CLN3 mutation, typically presents between 4 and 8 years of age with progressive visual loss leading to complete blindness within 2–4 years of onset. Seizures of variable subtypes usually follow by the end of the first decade or middle of the second decade, along with motor and cognitive regression, movement disorder often including extrapyramidal signs and neuropsychiatric disturbances. Most patients live into their late teens and early twenties, but some may live into their thirties and, rarely, beyond. Emerging clinical evidence also points to JNCL pathology outside the CNS, including the immune system and the cardiovascular system. It has been discovered that JNCL patients produce autoantibodies to GAD65 and α-fetoprotein, although the precise etiology and consequences of these circulating antibodies are not yet completely understood [5,6]. Moreover, in a recent study, cardiac abnormalities were detected by ECG in nearly half of the 29 JNCL patients in the cohort. The abnormalities reported included T-wave inversion, sinus node dysfunction and ventricular hypertrophy, which were relatively late findings in the disease course, occurring no earlier than age 14 [7]. These findings are consistent with an autopsy series of three JNCL patients that demonstrated biventricular hypertrophy, dilation and degenerative myocardial changes accompanied by preferential accumulation of storage material in the conduction system [8]. A second more recent study also reported cardiac defects in approximately one half of the JNCL patients participating in the study [9]. Thus, while JNCL is primarily a neurodegenerative disease, it is increasingly apparent that CLN3 mutations may influence other organ systems in addition to the CNS, particularly later in the disease course, which is consistent with the ubiquitous tissue expression of the CLN3 gene.

Biochemical analysis of the NCL lysosomal storage material has provided some important insight into the disease pathophysiology [10]. Ceroid lipofuscin in NCL is heterogeneous, containing dolichols, dolichol phosphates and iron, although it is mainly composed of proteins and alcohol-insoluble lipids. The predominant accumulating proteins associated with granular osmiophilic deposits are the saposins (SAPs; primarily variants A and D), which are sphingolipid activator proteins derived by differential lysosomal proteolysis of a glycosylated approximately 70 kDa precursor, prosaposin (PSAP; reviewed in [11,12]). In CL, rectilinear and FP inclusions, the predominant accumulating protein is subunit c of the mitochondrial ATP synthase F0 (hereafter referred to as ‘subunit c’), which is the pore forming, membrane-spanning subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex [13,14]. SAP storage suggests involvement of sphingolipid metablism in NCL pathophysiology, whereas subunit c accumulation implicates a role for autophagy [15], the process that coordinates the lysosomal turnover of macromolecules and cellular organelles, including mitochondria. While the NCLs are often classified into SAP storage and subunit c storage subtypes, there is increasing evidence supporting a spectrum of storage material profiles among the NCLs that is predicted by genotype (Figure 1) [16,17]. Consistent with an overlapping NCL pathological spectrum, it is also likely that the genes involved in NCL serve functions in common biological processes and, at least in some cases, may participate in common protein complexes [18–20]. The evidence for potential relationships between the NCL proteins has recently been reviewed in detail elsewhere [21,22].

The CLN3 protein

Mutations in the CLN3 gene were first identified in JNCL patients in 1995 [23]. CLN3, which is localized to chromosome 16p11.2, encodes a 438-amino acid transmembrane protein predicted to have six transmembrane domains (Figure 2). CLN3 is widely believed to primarily localize to late endosomal and lysosomal membranes, although its precise function is unknown [2,21,22]. While the CLN3 protein sequence is unique, an early in silico prediction of CLN3 homologs using PSI-BLAST [24] revealed a distant but significant sequence similarity between CLN3 and members of the SLC29 family of equilibrative nucleoside transporters, of which four members are recognized in mammals [25,26]. More recent algorithms, such as the Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP [101]) and Pfam [102], predict that most of the CLN3 protein (amino acids 11–433) has a domain structure consistent with members of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS; SCOP superfamily 103473; Pfam clan CL0015) The MFS superfamily is one of the two largest families of membrane transporters and includes small-solute uniporters, symporters and antiporters found across bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes [27]. These permeases transport drugs, simple sugars, oligosaccharides, inositols, amino acids, nucleosides, organophosphate esters, Krebs cycle metabolites, and a large variety of organic and inorganic anions and cations. MFS transporters are single-polypeptide chains predicted, in most cases, to contain 12 transmembrane domains. These are believed to have arisen from a primordial internal tandem gene duplication event, as suggested by the similarity of the N- and C-terminal halves of the full-length proteins. While CLN3 most likely has six transmembrane domains [28], one study showed that myc tagged and nonglycosylated, overexpressed CLN3 formed an SDS-stable 88-kDa form, presumed to correspond to a CLN3 homodimer [29]. Whether endogenous, fully modified CLN3 also forms stable homodimers or functions as a transporter is not yet determined.

Figure 2. CLN3 topology and juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis mutations.

The predicted topology of CLN3 is depicted. Sites for post-translational modifications are shown (blue forked lines represent N-glycosylation, zigzag represents prenylation and dotted line represents a possible cleavage site following prenylation), and point mutations are marked by red (missense) and yellow (nonsense) colored circles. A reported polymorphism at residue 404 (H/R) is shown (dark blue). Residues E295 and Q352 are both red and yellow as they are sites for both missense and nonsense mutations.

†A residue that has been associated with slower disease, in compound heterozygosity with the common 1.02-kb deletion mutation.

‡A residue that has been associated with slower disease in homozygosity.

Intriguingly, mutations in MFSD8, which encodes a predicted 12-transmembrane lysosomal protein with strong primary sequence homology to other MFS proteins, cause a variant late-infantile form of NCL, referred to as CLN7, with an age of clinical onset between 2 and 8 years [30]. The transport properties and substrate specificity of MFSD8 remain to be elucidated, if indeed this novel protein functions like the other MFS family members. As in JNCL, ultrastructural pathology in CLN7 patients shows primarily condensed FP and CL inclusions, sometimes within vacuoles. Moreover, at least one case showed enlarged vacuoles within peripheral blood lymphocytes [30], a feature also seen in CLN3 patient lymphocytes, but not in lymphocytes from patients with other genetic forms of NCL [1].

It has also been reported that earlier versions of Pfam predicted that the N-terminus of CLN3 had a low level homology to fatty acid desaturases [31]. As a result of this homology, Narayan et al. examined fatty acid desaturase activity in an in vitro assay where cell or tissue lysates with CLN3 deficiency were added to various lipid and proteolipid substrates, and the subsequent level of desaturation was measured [31]. In this study, CLN3-deficient extracts, as compared with controls, possessed a dramatically reduced Δ9 desaturase activity, which creates a double bond at the 9th position from the carboxyl end of fatty acids. Loss of CLN3 appeared to show a relatively specific decrease in desaturase activity on palmitoyl (C16) moieties on protein substrates. Moreover, in a follow-up study, heterozygous Cln3-knockout mouse brain and pancreas lysates were shown to possess approximately 40% of the activity observed in the wild-type tissue lysates [32]. Importantly, however, these studies by Narayan and colleagues did not demonstrate that the CLN3 protein could directly catalyze the desaturation of the palmitoyl group, and despite broad CLN3 tissue expression, this activity was detected only in brain and pancreas, but not in other tissue lysates [32]. Therefore, whether this was a direct or indirect effect of the loss of CLN3 protein function primarily in neuronal and pancreatic tissue remains unclear, and whether there is a deficiency of Δ9 desaturase activity in JNCL patient neuronal and pancreatic cells is yet to be determined. Nevertheless, this was an intriguing finding pointing to a possible role for CLN3 in regulating proteins via posttranslational lipid modifications. The reported specificity of a CLN3-mediated desaturation activity for palmitoylated protein substrates is also notable given that the infantile form of NCL, CLN1, is caused by mutations in PPT1, which catalyzes the removal of palmitoyl groups from posttranslationally modified proteins [33]. Moreover, the role of palmitoylation in additional forms of NCL continues to evolve with the recent discovery of NCL-causing mutations in a new gene, DNAJC5, which encodes CSPα. The DNAJC5 p.Leu115Arg and p.Leu116del mutations found in NCL patients are believed to lead to less efficient palmitoylation of the protein, and hence altered stability and sorting to synaptic vesicles [34].

CLN3 mutations in JNCL

The majority of JNCL patients have a 1.02-kb genomic deletion mutation in common, which appears to be a founder mutation that arose in a common European ancestor [3,23]. Most patients are homozygous for this mutation (~74%), but a substantial number of patients are compound heterozygous for this and one of the other rare mutations (~22%), of which there are 39 to date. A small number of patients (~4%) are reported to have two of the rare mutations [35].

The mutations identified to date are listed in the NCL Mutation Database [103]. In addition to large deletions like the 1.02-kb common deletion, documented mutations include indel, missense, nonsense and splice site mutations. Mapping the missense and nonsense mutations on a CLN3 topological model reveals that most of these mutations localize to the luminal side of the transmembrane structure (see red and yellow colored amino acid residues in Figure 2). Of particular note are luminal loop 2, which is also one of the most highly conserved domains across species [36,37] and encompasses the protein sequence encoded by exons 7 and 8 that is excised by the common 1.02-kb deletion mutation, and a predicted amphipathic helix on the luminal face between the 5th and 6th transmembrane helices (Figure 2) [28]. The clustering of most of the missense mutations in these two luminal regions strongly implies that they are critical sites for protein or ligand–substrate binding to mediate CLN3 function. Two point mutations in the C-terminal tail, which lies on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane, also highlight the importance of this domain in mediating CLN3 protein structure and/or function.

It is worth noting that patients with several of the rare mutations have a more protracted disease course compared with that seen in classical JNCL. Sarpong et al. reported on five affected siblings from a large consanguineous family from Lebanon who were homozygous for a novel mutation that introduces a stop codon at Tyr199 (p.Tyr199X) and had a protracted disease course, particularly in the rate of motor and cognitive skill decline [38]. Molecular analysis in the study indicated that the mutant variant mRNA was expressed at similar levels to the wild-type mRNA, suggesting little, if any, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of this mutant CLN3 message. Together, these observations suggest that the N-terminal half of CLN3 possesses partial function, if the predicted consequence of the nonsense mutation, to yield a truncated CLN3 protein, is borne out in follow-up studies. The p.Leu101Pro, p.Leu170Pro and p.Glu295Lys mutations, in compound heterozygosity with the common 1.02-kb deletion, have also been reported to lead to a protracted disease [3,35,39]. Functional studies of these CLN3 protein variants suggest that the amino acid changes lead to less efficient CLN3 folding, stability and/or trafficking, but that some normal protein activity is retained, which is supported by observations that the mutant variants can also partially rescue CLN3-deficiency phenotypes [36,40,41]. These are key observations that merit further study, since drugs that may improve the trafficking, stability and function of these variants could help some JNCL patients.

The CLN3 protein bears consensus sites for N-glycosylation, phosphorylation and C-terminal lipid modification, including myristoylation, palmitoylation and prenylation; experimental data validates these predictions [29,42–45]. These protein modifications most likely modulate CLN3 protein stability and regulate function. CLN3 also has two domains that likely mediate lysosomal targeting (Figure 2) [46–48]. Interestingly, no mutations associated with JNCL have altered the lysosomal targeting motifs directly. Emerging data in support of additional subcellular sites of CLN3 protein function will be discussed in more detail later in this review.

In addition to the full-length protein encoded by 15 exons [23], alternative CLN3 protein variants may also exist. Multiple alternatively spliced CLN3 mRNAs have been detected in sheep [49], and at least ten human mRNA variants are reported in Genbank that align with the CLN3 locus in the UCSC genome browser [104]. A CLN3-like (CLN3L) protein purported to be encoded by a distinct gene has also been reported (Genbank accession numbers BK001540, AK090709 and AX746584) [50]. However, the cDNAs in reference to the CLN3L protein align precisely with the CLN3 locus in the most current human genome assembly (February 2009 build) within the UCSC genome browser, and analysis of the alignment indicates that they represent an alternative CLN3 transcript that retains introns 10 and 11, which is predicted to cause a frameshift after exon 10 yielding a shorter C-terminal CLN3 protein variant. Intriguingly, the CLN3 locus on chromosome 16 has been reported to have heterozygous deletions that are associated with developmental delay and the autism spectrum disorders (16p11.2 microdeletion syndromes), and in some cases, the entire CLN3 gene is deleted [51,52]. It is noteworthy then that, to our knowledge, a whole CLN3 gene deletion has never been associated with a case of JNCL.

The common 1.02-kb deletion mutation causing JNCL in most patients effectively deletes the sequence between intron 6 and intron 8, which predicts a frameshift in the coding sequence of exon 9 and a premature stop codon [23]. Given the complexities and incomplete understanding of CLN3 gene regulation, we have previously analyzed the impact of the common JNCL mutation on Cln3 gene expression in tissues and cultured cells from Cln3Δex7/8 knock-in mice, which were genetically manipulated to bear a nearly identical mutation to the common 1.02-kb deletion in the endogenous murine Cln3 gene [53–55]. Studies in the mouse genetic replicas indicated that the approximately 1-kb genomic deletion leads to a three- to tenfold reduction in Cln3 mRNA levels, implying that nonsense-mediated decay or other quality control pathways partly, but not completely, eliminate Cln3 mutant message in a manner that may be influenced by tissue type [53]. Multiple stable, alternatively spliced mRNAs are present in genetically accurate mouse cells and tissues bearing the common JNCL mutation. Most prominent among them is the variant deleted for exons 7 and 8, which, if translated, encodes a mutant protein with wild-type amino acids 1–153, plus a stretch of 28 novel amino acids before the premature stop codon [23]. Additional mutant splice variants have been reproducibly detected in the mouse model systems as well, including a splice variant deleted for exons 5, 7 and 8 (exon 5/7/8del) and predicted to encode a protein with an internal deletion and a 29-amino acid internal substitution, but otherwise intact N- and C-termini [53]. This exon 5/7/8del splice variant has also been reported in GenBank in association with JNCL patient cells bearing the 1.02-kb common deletion (GenBank accession no. AF015598), and consistent with the Cln3Δex7/8 mouse data, stable CLN3 mRNA has been detected in JNCL patient cells in multiple studies [23,38]. The net effect of the exon 5/7/8del variant at the protein level is predicted to remove the second, third and fourth transmembrane domains and intervening second large luminal loop of full-length CLN3 (Figure 2). Such a protein, if synthesized, would be predicted to retain its lysosomal targeting signals and the amphipathic helical domain on the luminal face of the membrane that appears to be an important functional domain given the cluster of missense mutations present within it (Figure 2).

Whether a stable protein is produced from the mutant CLN3 mRNAs transcribed from the common 1.02-kb deletion allele remains controversial [56]. In support of this possibility, residual staining with CLN3 antibodies has been observed in tissues and cells from homozygous Cln3Δex7/8 mice at levels that are consistent with the relative mRNA expression level data [53–55]. One study has also reported worsening of phenotypes following human CLN3 siRNA knockdown in JNCL patient cells in an effort to determine the effect of reduced expression of mutant gene products, if they indeed exist [57]. However, further studies are needed to resolve whether these results represent a lack of CLN3 antibody specificity and off-target effects of CLN3 siRNAs, respectively, or whether mutant CLN3 proteins retaining some residual function are indeed present in the majority of JNCL patients. If the latter is proven true, upregulation of the mutant gene products will be an important strategy in JNCL drug development.

CLN3 protein trafficking & its likely role in the endosomal–lysosomal pathway

CLN3 protein that is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and further processed in the Golgi complex travels from the Golgi to multiple subcellular membranes. The protein has two lysosomal targeting motifs (EEEX8LI and MX9G, highlighted in Figure 2), which were identified by two independent groups [46,47]. Kyttala and colleagues demonstrated evidence that these motifs mediate sorting and lysosomal targeting of CLN3 by binding to adaptor proteins AP1 and AP3 [48], although Storch and colleagues were unable to demonstrate dependence on interactions with adaptor proteins [47], a discrepancy that may be explained by the different cell systems used by the two groups. CLN3 protein sorted from the Golgi appears to traffic into early and late endosomes and is subsequently delivered to lysosomes. CLN3 may also traffic out to the plasma membrane where it would subsequently be internalized into the endocytic system [29,46–48]. In addition to the lysosomal targeting motifs and adaptor sorting machinery, other mechanisms that may participate in CLN3 sorting include C-terminal prenylation, most likely in the form of farnesylation [29,58], and binding to glycosphingolipids that accumulate in raft microdomains [59].

Multiple lines of evidence implicate CLN3 function within endosomes and lysosomes. Endogenous CLN3 from mouse liver tissue is highly enriched in lysosomal fractions, but is not strongly detected in endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi fractions [43,60]. Consistent with its presence in the endosomal–lysosomal system, JNCL patient cells and genetic models of JNCL harbor defects in lysosomal acidification [36,61,62], amino acid transport into the lysosome [63], deficiencies in bulk endocytosis [54,64,65] and a defect in the maturation of autophagosomes, a step that requires fusion with functional endosomes and/or lysosomes [60]. It is noteworthy that all of these cellular defects occur in the absence of detectable lysosomal storage, implying that these are upstream events that lie close to CLN3’s primary function. This function may be mediated through protein complexes involving CLN3 and other endosomal and lysosomal proteins including Hook 1, TPP1 and CLN5, which have each been demonstrated to interact with overexpressed CLN3 in GST-pulldown and coimmunoprecipitation studies, although these interactions have not yet been demonstrated to occur between the endogenous proteins [18,64]. TPP1 and CLN5 are the proteins whose functions are disrupted in late-infantile NCL (CLN2) and a variant late-infantile NCL (CLN5), respectively, supporting the possibility that at least some of the NCL proteins may function together in a complex.

Accumulating evidence also supports CLN3 function at the plasma membrane or in vesicular compartments close to and in communication with the plasma membrane, particularly in neurons. Luiro and colleagues reported that endogenous CLN3 in neurons is enriched in synaptosomal fractions isolated from nerve terminals [66], and alterations in neurotransmitter and receptor levels and in activation of receptors at the synapse in Cln3 genetic mouse models have been documented [67–69]. CLN3 function near the plasma membrane may involve interaction with components that regulate the actin cytoskeleton (β-fodrin and nonmuscle myosin-IIB) [70,71], with lipid rafts that are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids such as galactosylceramide [59,72], and/or with ion channels or their accessory proteins (Na+/K+ ATPase, calsenilin/KChip3) (Figure 3) [70,73]. These interactions may mediate directed trafficking of membrane proteins and lipids, particularly sphingolipids and cholesterol from lipid raft microdomains, which may have immediate and downstream effects on cell survival and ion homeostasis [59,72–74].

Figure 3. The CLN3 protein mediates anterograde and retrograde trafficking in a pathway connecting the Golgi network, endosomes, autophagosomes, lysosomes and plasma membrane.

Upon synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum and glycosylation in the Golgi, CLN3 has several potential fates that may in part be mediated by compartment-specific interacting proteins. The sorting of CLN3 into post-Golgi transport vesicles may be directed by adaptor proteins AP-1 and AP-3 in clathrin-coated membrane buds from the trans-Golgi network. A significant proportion of CLN3 then enters late endosomes, which undergo acidification to form lysosomes. A portion of the lysosomal pool fuses with autophagosomes, double membrane structures that may be derived from the Golgi (as shown) or other sources, including the endoplasmic reticulum and endosomes (not shown). CLN3 may interact with a complex of autophagy proteins including Atg3 and Atg7, which catalyze the addition of phosphatidylethanolamine to LC3 to form LC3-II, a proteolipid that assembles into the inner and outer membranes of the nascent phagophore and promotes its extension to a mature autophagosome. An undetermined fraction of CLN3 may be directed from transport vesicles to the plasma membrane or from late endosomes to the plasma membrane, where it may interact with components of the membrane cytoskeleton such as nonmuscle myosin-IIB and fodrin, which links plasma membrane proteins such as the Na+/K+-ATPase to the actin cytoskeletion. Whether CLN3 interacts with these proteins as an endosomal protein (as shown) or as a plasma membrane protein is unclear. The possible interaction of CLN3 with AP-2, the adaptor protein involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis of plasma membrane proteins (labeled as cargo receptors), is less clear. A portion of CLN3 may facilitate the transport of sphingolipids, including GalCer, from the trans Golgi to the plasma membrane. Recent evidence in yeast models suggests that CLN3 or its yeast ortholog Btn1 (shown) is involved in retrograde transport from the endocytic compartment to the trans-Golgi network. This may be mediated indirectly by assembly of the SNARE protein Sed5, which must be phosphorylated to direct retrograde transport. Sed5 is either directly or indirectly phosphorylated by the palmitoylated endosome- and vacuole-associated casein kinase Yck3. It was speculated that Btn1p may exert a desaturase activity on the palmitoyl moiety of Yck3 and thereby promote its activation of Sed5. CLN3 interactors are shown in red text.

GalCer: Galactosylceramide.

Recent advances in lower eukaryotic models support a role for CLN3 in regulating post-Golgi anterograde & retrograde trafficking

CLN3 may also exert its influence on the trafficking of proteins and lipids to the other membrane compartments via a function that is localized to the Golgi complex. As already indicated, most studies that have investigated CLN3 trafficking and localization have demonstrated some proportion of overexpressed CLN3 in the Golgi. One interpretation of these overlapping observations is that CLN3 traffics through this compartment en route to its primary residence, and that more or less of the protein may localize there depending on its level of overexpression and the presence and position of a fused tag, which may influence folding and posttranslational modification [75]. However, it is also plausible that CLN3 functions in the Golgi. Indeed, localization of endogenous CLN3 to the Golgi has also been reported [59].

The Golgi complex is the main site for the final synthesis steps and subsequent sorting of lipids and proteins that distribute to the other membrane compartments of the cell in complex and highly coordinated pathways that are only partly understood. The Golgi is also intimately connected to the endocytic pathway, receiving lipid and protein cargo from the endosomallysosomal system and the plasma membrane for recycling (for recent reviews, see [76]). Recent genetic studies, mostly in lower eukaryotic yeast models of JNCL, which are well established for genetic manipulation and cell biological studies, have provided compelling evidence in further support of the hypothesis that CLN3 functions in or near the trans-Golgi network, upstream of the lysosome.

As in mammalian cells, overexpressed Btn1p, the CLN3 ortholog in budding and fission yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, respectively) is transported to the vacuole (the yeast equivalent of the mammalian cell lysosome) via post-Golgi trafficking through endosomal compartments [36,77,78]. Moreover, deletion of the btn1 gene in yeast leads to vacuolar defects, including altered pH and amino acid transport [36,63,79] and increased vacuole size (in S. pombe [36]), phenotypes that were all rescued by exogenous expression of human CLN3, indicating that CLN3 function is conserved between yeast and humans, strongly supporting the rationale for studies of these lower eukaryotic models to gain insight into the human disease mechanisms.

Recent studies have indicated that Btn1p may also regulate the vacuole from the trans-Golgi network. For example, in S. pombe, deletion of btn1 resulted in a disruption in Golgi morphology and deficient post-Golgi sorting of proteins including Vps10p, the mannose 6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) ortholog that is responsible for sorting lysosomally targeted soluble enzymes [80]. Consistent with the findings in S. pombe, Golgi–lysosome trafficking defects, including those of M6PR, have also been found in mammalian cells with CLN3 deficiency [54,81]. M6PR missorting may lead to more global lysosomal hydrolase mistargeting in the absense of functional CLN3, leading to vacuolar dysfunction.

Most recently, Kama and colleagues have further delineated a role for Btn1p in trafficking between Golgi and endosomal compartments in S. cerevisiae [78]. Building on earlier S. cerevisiae studies surrounding btn1, and on studies of btn2, which is a Hook ortholog in yeast that is upregulated in btn1Δ cells and is involved in late endosome–Golgi retrograde transport [82–84], Kama et al. examined whether Btn1p also functioned in this organism to regulate late endosome-Golgi retrograde transport. In btn1Δ cells, localization of proteins that are normally recycled from the vacuole to the Golgi was disrupted, and the mechanism by which Btn1p exerted this effect involved Sed5 (a SNARE protein) and its regulatory kinase, Yck3 (casein kinase II ortholog) [78]. Btn1p overexpression also altered the pathway, reducing the degree of Sed5 assembly with other SNARE proteins, including Ykt6, which have recently been shown to be required for the initiating events in autophagosome membrane formation in autophagy [85]. This is noteworthy because we have previously demonstrated that CLN3-deficient mammalian cells harbor deficiencies in autophagy pathway trafficking [60], and in a recent gene expression study using the same cells, we found that Ykt6 gene expression was significantly increased (~1.4-fold) by gene expression microarray (GSE24368 in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus [105]), quantitative reverse transcription-PCR and by western blot analysis [Cotman SL, Staropoli JF, Unpublished Data]. Moreover, CLN3 may indirectly or directly interact with other components of the autophagy machinery, including ATG7 (Figure 3) [86]. Given these observations and the fact that the mechanisms of autophagy have largely been defined in yeast [87,88], future studies of autophagy trafficking in yeast CLN3 deficiency models are warranted.

Intriguingly, Yck3 is a palmitoylated kinase that mediates Golgi-vacuole sorting and vacuolar fusion in a palmitoylation-dependent manner. In the study by Kama et al., the requirement for Btn1p in normal sorting was overcome by replacement of the Yck3 palmitoylation domain with a transmembrane domain, suggesting that Btn1p regulates sorting through modulation of this lipid modification, either directly or indirectly [78]. This is a key observation in support of the claim by Narayan et al. that CLN3 is a palmitoyl protein desaturase [31]. Notably, Ykt6 is also palmitoylated, and it has been demonstrated that this modification is required for its trafficking [89]. While further study is still needed to determine whether CLN3 directly or indirectly modulates palmitoylated proteins, taken together, the data from yeast and mammalian cell systems are converging on important functions for CLN3 in regulating trafficking between the Golgi, plasma membrane and the endosomal–lysosomal system that is likely to influence the biology of lysosomes, and which may have a particularly significant impact at neuronal synapses, where highly coordinated lipid and protein trafficking events are required.

Future perspective

Consolidating a decade of studies on CLN3 localization and function in lower eukaryotic and mammalian systems implies that this protein resides and functions in multiple subcellular compartments including the Golgi network, the plasma membrane, and endosomal and lysosomal compartments, to coordinate protein and lipid trafficking and turnover. The specific processes that govern sorting events in different cell types may in turn influence the precise downstream effects of CLN3 function. This may explain the seemingly contradictory data in the literature surrounding CLN3 localization and the sometimes variable phenotypes across different models of CLN3 deficiency. In the coming years, there will undoubtedly be continued research efforts focused on precisely delineating CLN3 gene regulation and expression, cell-type specific localization and function. A specific emphasis on several research areas that are likely to yield new approaches to develop and monitor putative JNCL therapies is particularly warranted:

Focused efforts aimed at defining the impact of CLN3 deficiency on the trans-Golgi network in mammalian cells should be pursued.

Further defining the mechanisms by which CLN3 regulates lipids and lipid-modified proteins should be pursued.

The btn1 yeast models provide an important resource to further define the mechanistic underpinnings of the autophagy defects as a result of CLN3/Btn1p deficiency. As with any JNCL model system, it will also be important to subsequently test the new hypotheses that emerge in human model systems, particularly in induced pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed from JNCL patient somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts and lymphoblasts) and their differentiated derivative cell types.

Expanded efforts to improve the clinical picture of JNCL, and how this compares to other forms of NCL, should be emphasized. In particular, expanding the understanding of non-neurological symptoms may substantially improve patient care. As new therapies are proposed and are moved into clinical testing, monitoring their efficacy will require new biomarkers and an improved definition of the natural history of JNCL.

Executive summary.

Juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis is a lysosomal disease that causes neurodegeneration in children

Juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) is one of at least nine genetically defined forms of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL). Autosomal recessive forms of NCL collectively comprise the most common Mendelian form of childhood-onset neurodegeneration.

JNCL, caused by mutations in CLN3, is usually heralded by visual loss and eventually blindness caused by pigmentary retinopathy and is accompanied or followed by seizures, cognitive and motor regression, movement disorder, neuropsychiatric disturbances and death usually by the third decade.

Though primarily defined as a neurodegenerative disorder, JNCL is likely to be a multisystem disease extending, for example, to the cardiovascular system, as later-stage patients show conduction anomalies and ventricular hypertrophy.

‘Ceroid lipofuscin’ in NCL is lysosomal storage material taking on one of several characteristic ultrastructural morphologies and composed primarily of proteins and alcohol-insoluble lipids. The protein component consists mostly of sphingolipid activator proteins A and D and subunit c of the mitochondrial ATP synthase F0 complex. The relative proportions of these proteins within the storage material most likely fall on a continuous spectrum that may be correlated with specific genetic forms of NCL.

The CLN3 protein

CLN3 is a predicted six-pass transmembrane protein with diverse proposed functions and localizations that may, in part, be determined by its interactions with one of several candidate-interacting proteins.

CLN3 bears distant homology to equilibrative nucleoside transporters, the major facilitator superfamily of transporters and fatty acid desaturases. Whether CLN3 possesses transporter or desaturase activity requires further study.

CLN3 protein trafficking & its likely role in the endosomal–lysosomal pathway

Model systems of CLN3 deficiency from yeast to human cell culture systems have established a central role for CLN3 in lysosomal function and in trafficking between the endosomal and lysosomal systems. CLN3 has two experimentally demonstrated motifs, one in a cytoplasmic loop (EEEX8LI) and another in the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (MX9G), that direct glycosylated CLN3 from the Golgi to lysosomes, possibly via early and/or late endosomes.

CLN3 may also function at or near the plasma membrane to facilitate the incorporation of sphingolipids, such as galactosylceramide, into lipid raft microdomains, or coordinate the interaction between plasma membrane proteins such as the Na+/K+ ATPase and the actin cytoskeleton.

Recent advances in lower eukaryotic models support a role for CLN3 in regulating post-Golgi anterograde & retrograde trafficking

CLN3 deficiency in yeast and mammalian cells leads to mis-sorting of the mannose 6-phosphate receptor to the lysosome. This is likely to lead to the mistargeting of lysosomal hydrolases, which are usually trafficked to the lysosome via mannose 6-phosphate moieties recognized by the mannose 6-phosphate receptor.

Btn1p, the yeast CLN3 ortholog, also appears to regulate transport of a subset of proteins that are normally recycled from the vacuole (the yeast equivalent of the lysosome) to the trans-Golgi network. Btn1p exerts this effect indirectly through the SNARE protein Sed5, which mediates retrograde transport in its phosphorylated state. Sed5 is either directly or indirectly phosphorylated by the palmitoylated endosome- and vacuole-associated casein kinase II ortholog, Yck3.

Btn1p may use a palmitoyl desaturase activity to regulate the action of Yck3 upon Sed5. This speculation arose from a Δ9 desaturase activity, relatively specific for palmitoyl moieties, that was found to be significantly reduced in vitro in mammalian CLN3-deficient extracts. The possible relevance of protein palmitoylation more broadly among the NCLs is highlighted by the infantile form of the disease, CLN1, caused by mutations in palmitoyl protein thioesterase and an adult-onset, autosomal dominant form of NCL caused by mutations in CSPα that affect its palmitoylation, stability and sorting to synaptic vesicles.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact: reprints@futuremedicine.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors of this review are supported by grants from the Batten Disease Support and Research Association (both authors), the Dubai-Harvard Foundation for Medical Research (SL Cotman) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH (NS073813, SL Cotman). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Kohlschutter A, Schulz A. Towards understanding the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Brain Dev. 2009;31(7):499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalanko A, Braulke T. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(4):697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3▪▪.Mole S, Williams R, Goebel H. The Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (Batten Disease) 2. Oxford University Press; UK: 2011. Comprehensive review of the clinicopathologic features of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), the spectrum of mutations in each of the NCL genes known at the time of its publication, the genetic models that have been developed for each form of the disease and the proposed functions of each of the proteins encoded by the NCL genes. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mole S, Williams R, Goebel H. Correlations between genotype, ultrastructural morphology and clinical phenotype in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Neurogenetics. 2005;6(3):107–126. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay S, Ito M, Cooper J, et al. An autoantibody inhibitory to glutamic acid decarboxylase in the neurodegenerative disorder Batten disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(12):1421–1431. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.12.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castaneda J, Pearce D. Identification of alpha-fetoprotein as an autoantigen in juvenile Batten disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7▪▪.Ostergaard J, Rasmussen T, Molgaard H. Cardiac involvement in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease) Neurology. 2011;76(14):1245–1251. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821435bd. First study to closely examine the cardiovascular system in a cohort of genetically defined juvenile-onset NCL (JNCL) patients. Case reports had previously indicated the possibility of cardiac defects in JNCL patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofman I, van der Wal A, Dingemans K, Becker A. Cardiac pathology in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses – a clinicopathologic correlation in three patients. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(Suppl A):213–217. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebrun A, Moll-Khosrawi P, Pohl S, et al. Analysis of potential biomarkers and modifier genes affecting the clinical course of CLN3 disease. Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00241. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seehafer S, Pearce D. You say lipofuscin, we say ceroid: defining autofluorescent storage material. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(4):576–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruhn H. A short guided tour through functional and structural features of saposin-like proteins. Biochem J. 2005;389(Pt 2):249–257. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda J, Yoneshige A, Suzuki K. The function of sphingolipids in the nervous system: lessons learnt from mouse models of specific sphingolipid activator protein deficiencies. J Neurochem. 2007;103(Suppl 1):32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer D, Fearnley I, Walker J, et al. Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c storage in the ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(4):561–567. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer D, Bayliss S, Westlake V. Batten disease and the ATP synthase subunit c turnover pathway: raising antibodies to subunit c. Am J Med Genet. 1995;57(2):260–265. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320570230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kominami E. What are the requirements for lysosomal degradation of subunit c of mitochondrial ATPase? IUBMB Life. 2002;54(2):89–90. doi: 10.1080/15216540214307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ju W, Wronska A, Moroziewicz D, et al. Genotype-phenotype analyses of classic neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCLs): genetic predictions from clinical and pathological findings. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006;38(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyynela J, Baumann M, Henseler M, Sandhoff K, Haltia M. Sphingolipid activator proteins in the neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses: an immunological study. Acta Neuropathol. 1995;89(5):391–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00307641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyly A, Von Schantz C, Heine C, et al. Novel interactions of CLN5 support molecular networking between neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis proteins. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persaud-Sawin D-A, Mousallem T, Wang C, Zucker A, Kominami E, Boustany R-M. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: a common pathway? Pediatr Res. 2007;61(2):146–152. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31802d8a4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vesa J, Chin M, Oelgeschlager K, et al. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses are connected at molecular level: interaction of CLN5 protein with CLN2 and CLN3. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(7):2410–2420. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Getty A, Pearce D. Interactions of the proteins of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: clues to function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(3):453–474. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyttala A, Lahtinen U, Braulke T, Hofmann S. Functional biology of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL) proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762(10):920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease, CLN3. The International Batten Disease Consortium. Cell. 1995;82(6):949–957. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul S, Madden T, Schaffer A, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldwin S, Beal P, Yao S, King A, Cass C, Young J. The equilibrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC29. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447(5):735–743. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ackley M, Governo R, Cass C, Young J, Baldwin S, King A. Control of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the rat spinal dorsal horn by the nucleoside transporter ENT1. J Physiol. 2003;548(Pt 2):507–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao S, Paulsen I, Saier M., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(1):1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nugent T, Mole S, Jones D. The transmembrane topology of Batten disease protein CLN3 determined by consensus computational prediction constrained by experimental data. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(7):1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storch S, Pohl S, Quitsch A, Falley K, Braulke T. C-terminal prenylation of the CLN3 membrane glycoprotein is required for efficient endosomal sorting to lysosomes. Traffic. 2007;8(4):431–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siintola E, Topcu M, Aula N, et al. The novel neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis gene MFSD8 encodes a putative lysosomal transporter. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(1):136–146. doi: 10.1086/518902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31▪.Narayan S, Rakheja D, Tan L, Pastor J, Bennett M. CLN3P, the Batten’s disease protein, is a novel palmitoyl-protein Delta-9 desaturase. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(5):570–577. doi: 10.1002/ana.20975. Based on a low-homology in silico prediction that CLN3 was a fatty acid desaturase, the authors identified a relatively specific defect in Δ9 desaturation of palmitoyl groups in extracts from cells with CLN3 deficiency. This raised the possibility that CLN3 may regulate palmitoylated proteins via modulation of the lipid moiety, which is supported by another recent study in Btn1Δ yeast. However, it is still unclear whether CLN3 plays a direct or indirect role in modulation of palmitoylated proteins. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayan S, Tan L, Bennett M. Intermediate levels of neuronal palmitoyl-protein Δ-9 desaturase in heterozygotes for murine Batten disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93(1):89–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann S, Atashband A, Cho S, Das A, Gupta P, Lu Jy. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses caused by defects in soluble lysosomal enzymes (CLN1 and CLN2) Curr Mol Med. 2002;2(5):423–437. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noskova L, Stranecky V, Hartmannova H, et al. Mutations in DNAJC5, encoding cysteine-string protein alpha, cause autosomal-dominant adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munroe P, Mitchison H, O’Rawe A, et al. Spectrum of mutations in the Batten disease gene, CLN3. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61(2):310–316. doi: 10.1086/514846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36▪▪.Gachet Y, Codlin S, Hyams J, Mole S. btn1, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homologue of the human Batten disease gene CLN3, regulates vacuole homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 23):5525–5536. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02656. Describes phenotypes in a new yeast model of JNCL. Using genetic approaches, it was shown that btn1, the yeast CLN3 ortholog, is likely to function in prevacuolar compartments, to regulate post-Golgi sorting into endosomes and lysosomes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muzaffar N, Pearce D. Analysis of NCL Proteins from an evolutionary standpoint. Curr Genom. 2008;9(2):115–136. doi: 10.2174/138920208784139573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarpong A, Schottmann G, Ruther K, et al. Protracted course of juvenile ceroid lipofuscinosis associated with a novel CLN3 mutation (p.Y199X) Clin Genet. 2009;76(1):38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aberg L, Lauronen L, Hamalainen J, Mole S, Autti T. A 30-year follow-up of a neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis patient with mutations in CLN3 and protracted disease course. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40(2):134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haskell R, Carr C, Pearce D, Bennett M, Davidson B. Batten disease: evaluation of CLN3 mutations on protein localization and function. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(5):735–744. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golabek A, Kida E, Walus M, Kaczmarski W, Wujek P, Wisniewski K. CLN3 disease process: missense point mutations and protein depletion in vitro. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(Suppl A):81–88. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michalewski M, Kaczmarski W, Golabek A, Kida E, Kaczmarski A, Wisniewski K. Evidence for phosphorylation of CLN3 protein associated with Batten disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253(2):458–462. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ezaki J, Takeda-Ezaki M, Koike M, et al. Characterization of Cln3p, the gene product responsible for juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, as a lysosomal integral membrane glycoprotein. J Neurochem. 2003;87(5):1296–1308. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarvela I, Sainio M, Rantamaki T, et al. Biosynthesis and intracellular targeting of the CLN3 protein defective in Batten disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(1):85–90. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kida E, Kaczmarski W, Golabek A, Kaczmarski A, Michalewski M, Wisniewski K. Analysis of intracellular distribution and trafficking of the CLN3 protein in fusion with the green fluorescent protein in vitro. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;66(4):265–271. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kyttala A, Ihrke G, Vesa J, Schell M, Luzio J. Two motifs target Batten disease protein CLN3 to lysosomes in transfected nonneuronal and neuronal cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1313–1323. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storch S, Pohl S, Braulke T. A dileucine motif and a cluster of acidic amino acids in the second cytoplasmic domain of the batten disease-related CLN3 protein are required for efficient lysosomal targeting. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53625–53634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kyttala A, Yliannala K, Schu P, Jalanko A, Luzio J. AP-1 and AP-3 facilitate lysosomal targeting of Batten disease protein CLN3 via its dileucine motif. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11):10277–10283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oswald M, Palmer D, Damak S. Splicing variants in sheep CLN3, the gene underlying juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67(2):169–175. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narayan S, Pastor J, Mitchison H, Bennett M. CLN3L, a novel protein related to the Batten disease protein, is overexpressed in Cln3−/− mice and in Batten disease. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 8):1748–1754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ballif B, Hornor S, Jenkins E, et al. Discovery of a previously unrecognized microdeletion syndrome of 16p11.2–p12.2. Nat Genet. 2007;39(9):1071–1073. doi: 10.1038/ng2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barge-Schaapveld D, Maas S, Polstra A, Knegt L, Hennekam R. The atypical 16p11.2 deletion: a not so atypical microdeletion syndrome? Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(5):1066–1072. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cotman S, Vrbanac V, Lebel L, et al. Cln3Δex7/8 knock-in mice with the common JNCL mutation exhibit progressive neurologic disease that begins before birth. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(22):2709–2721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.22.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fossale E, Wolf P, Espinola J, et al. Membrane trafficking and mitochondrial abnormalities precede subunit c deposition in a cerebellar cell model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. BMC Neurosci. 2004;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao Y, Staropoli J, Biswas S, et al. Distinct early molecular responses to mutations causing vLINCL and JNCL presage ATP synthase subunit c accumulation in cerebellar cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):E17118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan C, Mitchison H, Pearce D. Transcript and in silico analysis of CLN3 in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and associated mouse models. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(21):3332–3339. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitzmuller C, Haines R, Codlin S, Cutler D, Mole S. A function retained by the common mutant CLN3 protein is responsible for the late onset of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(2):303–312. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pullarkat R, Morris G. Farnesylation of Batten disease CLN3 protein. Neuropediatrics. 1997;28(1):42–44. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Persaud-Sawin D, Mcnamara J, Vandongen R, Boustany R. A galactosylceramide binding domain is involved in trafficking of CLN3 from Golgi to rafts via recycling endosomes. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(3):449–463. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000136152.54638.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao Y, Espinola J, Fossale E, et al. Autophagy is disrupted in a knock-in mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(29):20483–20493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearce D, Sherman F. A yeast model for the study of Batten disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(12):6915–6918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holopainen J, Saarikoski J, Kinnunen P, Jarvela I. Elevated lysosomal pH in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs) Eur J Biochem. 2001;268(22):5851–5856. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim Y, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Pearce D. A role in vacuolar arginine transport for yeast Btn1p and for human CLN3, the protein defective in Batten disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(26):15458–15462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luiro K, Yliannala K, Ahtiainen L, et al. Interconnections of CLN3, Hook1 and Rab proteins link Batten disease to defects in the endocytic pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(23):3017–3027. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Codlin S, Haines R, Burden J, Mole S. Btn1 affects cytokinesis and cell-wall deposition by independent mechanisms, one of which is linked to dysregulation of vacuole pH. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 17):2860–2870. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luiro K, Kopra O, Lehtovirta M, Jalanko A. CLN3 protein is targeted to neuronal synapses but excluded from synaptic vesicles: new clues to Batten disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(19):2123–2131. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kovacs A, Weimer J, Pearce D. Selectively increased sensitivity of cerebellar granule cells to AMPA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in a mouse model of Batten disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(3):575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrmann P, Druckrey-Fiskaaen C, Kouznetsova E, et al. Developmental impairments of select neurotransmitter systems in brains of Cln3(Deltaex7/8) knock-in mice, an animal model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(8):1857–1870. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finn R, Kovacs A, Pearce D. Altered sensitivity of cerebellar granule cells to glutamate receptor overactivation in the Cln3(Deltaex7/8)-knock-in mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurochem Int. 2011;58(6):648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uusi-Rauva K, Luiro K, Tanhuanpaa K, et al. Novel interactions of CLN3 protein link Batten disease to dysregulation of fodrin–Na+, K+ ATPase complex. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(15):2895–2905. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Getty A, Benedict J, Pearce D. A novel interaction of CLN3 with nonmuscle myosin-IIB and defects in cell motility of Cln3−/− cells. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(1):51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rakheja D, Narayan S, Pastor J, Bennett M. CLN3P, the Batten disease protein, localizes to membrane lipid rafts (detergent-resistant membranes) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317(4):988–991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chang J, Choi H, Kim H, et al. Neuronal vulnerability of CLN3 deletion to calcium-induced cytotoxicity is mediated by calsenilin. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(3):317–326. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Persaud-Sawin D-A, Vandongen A, Boustany R-M. Motifs within the CLN3 protein: modulation of cell growth rates and apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(18):2129–2142. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Phillips S, Benedict J, Weimer J, Pearce D. CLN3, the protein associated with Batten disease: structure, function and localization. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:573–583. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Matteis MA, Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolfe DM, Padilla-Lopez S, Vitiello SP, Pearce DA. pH-dependent localization of Btn1p in the yeast model for Batten disease. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4(1):120–125. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78▪▪.Kama R, Kanneganti V, Ungermann C, Gerst J. The yeast Batten disease ortholog, Btn1, controls endosome–Golgi retrograde transport via SNARE assembly. J Cell Biol. 2011;195(2):203–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102115. Key genetic study in budding yeast, demonstrating that Btn1p, the yeast CLN3 ortholog, functions in the late endosome–Golgi retrograde trafficking pathway. Moreover, it was shown that Btn1p mediates this trafficking pathway by modulating Yck3 (casein kinase II), most likely through its palmitoylation moiety, which in turn regulates SNARE protein assembly, supporting the claim that CLN3 directly or indirectly regulates palmitoylated proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Padilla-Lopez S, Pearce D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking Btn1p modulate vacuolar ATPase activity in order to regulate pH imbalance in the vacuole. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(15):10273–10280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Codlin S, Mole SE. S. pombe btn1, the orthologue of the Batten disease gene CLN3, is required for vacuole protein sorting of Cpy1p and Golgi exit of Vps10p. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 8):1163–1173. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81▪.Metcalf D, Calvi A, Seaman M, Mitchison H, Cutler D. Loss of the Batten disease gene CLN3 prevents exit from the TGN of the mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Traffic. 2008;9(11):1905–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00807.x. Describes evidence that CLN3 deficiency leads to disrupted sorting of the mannose 6-phosphate receptor to lysosomes. This parallels similar findings in yeast models, strengthening the hypothesis that post-Golgi trafficking defects are a key component in JNCL pathogenesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pearce D, Ferea T, Nosel S, Das B, Sherman F. Action of BTN1, the yeast orthologue of the gene mutated in Batten disease. Nat Genet. 1999;22(1):55–58. doi: 10.1038/8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chattopadhyay S, Roberts P, Pearce D. The yeast model for Batten disease: a role for Btn2p in the trafficking of the Golgi-associated vesicular targeting protein, Yif1p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302(3):534–538. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kama R, Robinson M, Gerst J. Btn2, a Hook1 ortholog and potential Batten disease-related protein, mediates late endosome–Golgi protein sorting in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(2):605–621. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00699-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nair U, Jotwani A, Geng J, et al. SNARE proteins are required for macroautophagy. Cell. 2011;146(2):290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Behrends C, Sowa M, Gygi S, Harper J. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466(7302):68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang Z, Klionsky D. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:1–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mukaiyama H, Nakase M, Nakamura T, Kakinuma Y, Takegawa K. Autophagy in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(7):1327–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meiringer CT, Auffarth K, Hou H, Ungermann C. Depalmitoylation of Ykt6 prevents its entry into the multivesicular body pathway. Traffic. 2008;9(9):1510–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, et al. Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6898–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.SCOP: Structural Classification of Proteins, 1.75 release. 2009 Jun; http://scop.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/scop.

- 102.The Wellcome Trust. Sanger Institute. Pfam 26.0. 2011 Nov; http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk.

- 103.NCL Resource – A gateway for Batten disease. www.ucl.ac.uk/ncl.

- 104.UCSC Genome Bioinformatics. http://genome.ucsc.edu.

- 105.Gene expression omnibus. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE24368.