Graphical abstract

Insecticide imidacloprid application induced the susceptibility of rice to the brown planthopper and changes of gene expression levels of rice.

Highlights

► Microarray was used to identify changes in imidacloprid-induced rice gene expression. ► A total of 225 genes were differentially expressed following imidacloprid treatment. ► These differentially expressed genes were mainly classified into eight functional groups.

Keywords: Imidacloprid, Rice brown planthopper, Susceptibility, Microarray

Abstract

The chemical pesticide, imidacloprid (IMI) has long-lasting effectiveness against Hemiptera. IMI is commonly used to control the brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Some chemical pesticides, however, can induce the susceptibility of rice to BPH, which has indirectly led to the resurgence of BPH. The mechanism of the chemical induction of the susceptibility of rice to BPH was not previously understood. Here, a 44 K Agilent Rice Expression Microarray was used to identify changes in gene expression that accompany IMI-induced rice susceptibility to BPH. The results showed that 225 genes were differentially expressed, of which 117 were upregulated, and 108 were downregulated. Gene ontology annotation and pathway analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes were mainly classified into the eight functional groups: oxidation reduction, regulation of cellular process, response to stress, electron carrier activity, metabolic process, transport, signal transducer, and organismal development. The genes encoding plant lipid transfer protein, lignin peroxidase, and flavonol-3-O-methyltransferenase may be important responses to the IMI-induced susceptibility of rice to BPH. The reliability of the microarray data was verified by performing quantitative real-time PCR and the data provide valuable information for further study of the molecular mechanism of IMI-induced susceptibility of rice.

1. Introduction

In Southeast Asia and China, the resurgence of brown planthopper is thought to have been caused by the use of chemical pesticides [1,2]. The side effects of pesticides include the destruction of natural enemies [3,4], stimulation of reproduction of male and female adults [5], and pesticide-induced susceptibility of rice to BPH [6].

The brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) is a major pest of rice throughout Asia [7]. The BPH damages crops by phloem feeding, nutrient depletion, and by transmitting a number of rice pathogens. In addition, BPH occurrence is related to the resistance or susceptibility of the rice varieties [8]. When living on susceptible rice varieties, where BPH can acquire ample nutrients, the number of eggs laid and survival rates of eggs and nymphs are higher than on resistant varieties. At high rates of BPH feeding plants become completely desiccated, a condition known as “hopperburn”. However, when living on resistant varieties, BPH survival and ovipsition rates are significantly lower and BPH population growth is effectively suppressed [9–11]. Control of BPH relies heavily on insecticides, and most chemical classes used extensively against this pest have become compromised by insecticide resistance [12,13].

Neonicotinoids are the fastest-growing class of insecticides in modern crop protection [14]. This insecticide class has gained widespread use against a broad spectrum of sucking and certain chewing pests. Additional benefits of neonicotinoids include relatively low risk for non-target organisms and the environment, high target specificity, and versatility in application methods. This important insecticide class needs careful placement in insect resistance management in order to sustain its efficacy [15]. Imidacloprid (IMI), the first commercialised neonicotinoid insecticide, was introduced for planthopper control in the early 1990s. IMI proved extremely effective against insects that were resistant to compounds used previously. It consequently became the most commonly used insecticide against N. lugens over much of Asia. The wide application of IMI against pests has increased the risk of resistance in target insects [16,17]. This increased use has also resulted in various negative effects on crop plants and non-target insects [18,19]. For example, high doses of IMI reduced the length of the active growth stage, the grain weight, and the levels of the rice hormone zeatin riboside [20,21]. Insecticide-induced changes in plant quality have even been linked to the resurgence of N. lugens in rice [12]. The mechanism of insecticide-induced changes in plant quality is still unclear although this phenomenon has been widely observed.

More specifically, pesticide foliar sprays caused the increased infestation of rice by the BPH, also called pesticide-induced susceptibility [6]. However, the molecular mechanism of this susceptibility is not known. Thus, characterising the effect of IMI on gene expression in rice will provide a better understanding of insecticide-induced susceptibility to BPH.

Gene expression profiling by cDNA microarray is one of the most powerful tools for providing an overview of gene expression under various environmental stresses. Recently, several successful studies have examined plant gene expression profiles in response to pathogens [22,23], abiotic stress [24], and chemicals stress [25]. The Agilent Rice Oligo Microarray is a successful gene expression profile microarray. This chip represents more than 40,000 rice genes and transcripts, which allows for the comprehensive identification of imidacloprid-responsive genes.

The present study examined physiological and gene expression profile changes in the moderately resistant rice variety ZhenDao 2 after exposure to IMI. The objective of this study was to further elucidate the mechanism of insecticide-induced susceptibility to BPH.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Rice variety and insecticide

The rice (Oryza sativa L.) variety, Zhen Dao 2 (japonica rice) was used in the trials. This variety of rice was selected because it is sensitive to pesticide application [26]. Seeds were sown outdoors in a standard rice-growing soil in cement tanks (height 60 cm, width 100 cm, and length 200 cm). When the seedlings reached the six-leaf stage, they were transplanted into 16 cm diameter plastic pots with four hills per pot and three plants per hill. Rice plants at the tillering stage were used in the experiments.

IMI (10% WP, Yangnon Chemical Co., Ltd., Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China) was used in the trials. This insecticide was selected because its foliar spray significantly affects the physiology and biochemistry of rice plants [18]. Two concentrations, 30 and 60 ppm, were designed based on previous studies [20,21].

2.2. Imidacloprid treatment to rice

Foliar sprays were applied with 30 and 60 ppm IMI using a Jacto sprayer (Maquinas Agricolas Jacto S.A., Brazil) equipped with a cone nozzle (1 mm diameter orifice, pressure 45 psi, flow rate 300 ml/min). Control plants at the same stage of growth were sprayed with a mixture of adjuvants and tap water, similar in composition to the mixture containing the insecticide but lacking the active component. Each treatment and control was replicated three times, excluding the damage test following BPH infestation described in the following section. The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) and oxalic acid in the rice leaves and sheaths were measured 3, 6, and 9 days after IMI foliar sprays (3, 6, and 9 DAF). The rice sheaths at 6 DAF were used for the gene expression analysis.

2.3. Assessment of rice damage by BPH following IMI treatment

To examine whether IMI increased the susceptibility of rice to BPH infestation, resistance tests were conducted in 16 cm diameter plastic pots and arranged in a randomised complete block design. A single six-leaf seedling was transplanted to a plastic pot. Five days after transplantation, foliar sprays were conducted with the same concentrations of IMI and methods described above. Control plants were sprayed with a mixture of adjuvants and tap water, similar in composition to the mixture containing the insecticide but lacking its active component. Each treatment and control was replicated thirty times (30 pots). Thirty third-instar nymphs were released onto a single plant at 7 DAF, rather than immediately, so that there would be a lower residue concentration of imidacloprid and lower residue lethal efficacy to the third instar nymphs. Insect mortality was checked at 48 h after the release of nymphs, and dead nymphs (if any) were replaced with live nymphs of the same age to maintain a given density. The potted rice was then placed inside a cylindrical (25 × 25 cm) cage made of clear plastic film in order to prevent the nymphs from escaping. When BPH adults emerged (about 10 days after the release), the scale of damage to the rice plant was assessed according to a 9-level evaluation method, modified from the screening method used to determine the resistance of rice varietals [6]. The symptom description of a nine-scale injury rating was as follows:

Scale 1: slight injuries, few yellow pitches on leaf sheaths; scale 3: leaf sheaths slightly yellow; scale 5: leaf sheaths clearly yellow, reducing tillering; scale 7: leaf sheaths severely yellow, plant dwarfing and severely reduced tillering; scale 9: general withering [27].

2.4. Quantification of IMI-induced biochemical changes

MDA levels, oxalic acid levels, and photosynthetic capacity are important indicators of resistance to BPH [28–30]. We measured MDA, oxalic acid, leaf chlorophyll, and the photosynthetic rate of the rice plants to examine the susceptibility of rice plants to BPH after exposure to IMI.

MDA content was measured using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method [31]. Leaf blades were ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle, and 15 ml 0.1% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to 0.5 g frozen powder. This mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, and 4 ml 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was added to 1 mL of the supernatant (extracted solution). The supernatant with TBA was then bathed in boiling water for 30 min after evenly shaking. Next, the mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min after rapidly cooling on ice. The absorbance of the supernatant at 532, 450, and 600 nm was detected using a UV755 B spectrometer (Shanghai Precision Instrument Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). The value for non-specific absorption at 600 nm was subtracted, and a standard curve of sucrose (from 2.5 to 10 mol/mL) was used to rectify the results from the interference of soluble sugars in samples. The MDA concentration was calculated using the absorption coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1.

The photosynthetic rate of rice leaves was measured using a Li-6400 Portable Photosynthesis System (Li-COR Company, USA). Measurements were taken between 10:30 A.M. and 12:00 A.M. on sunny and calm days under relatively constant light intensity. Three rice leaves were tested per hill. The photosynthetic rate of control leaves was measured immediately after measuring the rate of treated leaves to minimise errors due to changes in light intensity.

Leaf chlorophyll content was determined using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Minolta, Japan). Three flag leaves for both IMI-treated and mock-treated plants were measured at 3 and 6 DAF, respectively. Three measurements at random positions in the centre of the leaf were taken for each plant, and the average of the three measurements was used for analysis. Ten leaves from each group with incrementally increasing chlorophyll levels (determined by SPAD-502 readings) were then harvested to construct a standard curve for the quantification of chlorophyll content using a previously validated method of chlorophyll analysis [32].

The titanium trichloride developing method was used to measure oxalic acid content [26]. Leaf sheaths were ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle, and 10 ml of distilled water was added to 0.5 g frozen powder. Active carbon was added to the sample solution to decolourise for 30 min, and the carbon was separated by centrifuging at 3500 rpm for 15 min. Decolourising was repeated using the same method described above until the solution was in a colourless or milk white state. Following decolourising, 240 μL of 3% titanium trichloride was added to 3 mL of supernatant, and the absorbance at 40 nm was detected using a UV755 B spectrometer (Shanghai Precision Instrument Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). A standard curve was constructed using 99.5% oxalic acid (Shanghai No.4 Reagent Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). The oxalic acid content of the sample solution was calculated based on the standard curve.

2.5. ‘Microarray analysis for IMI-induced transcriptional profiles

For microarray analysis, leaf sheaths from treated and control plants were collected 72 h after IMI treatment. Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen).

RNA samples from three biological replicates were purified by the RNeasy clean up system (Qiagen). The amount and quality of the RNA preparations were evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA6000 Nano Reagents and Supplies (Agilent).

For microarray hybridisation, 500 ng of RNA were reverse-transcribed to cDNA, during which a T7 sequence was introduced into the cDNA. The cDNA was prepared using T7 RNA polymerase-driven RNA synthesis. The cRNA was labelled with Cy3 (the treated sample) and Cy5 (the control sample), respectively. A Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was used to purify the fluorescent cRNA probes. An equal amount (1 μg) of Cy3 and Cy5 labelled probes were mixed and used for hybridisation on an Agilent 44 K Rice Whole Genome Microarray (Agilent), following the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Microarrays were scanned with an Agilent dual laser DNA microarray scanner using the parameters provided by Agilent (Red and Green PMT were each set at 100%, and the scan resolution was set to 10 μm). Feature Extraction Software v7.5 (Agilent Technologies) was used to extract and analyse the signals. Agilent-provided settings were used, except for the subtraction of the local background and adjustment of the global background. Poor quality features that were either nonuniform or saturated in the two channels (50% of pixels > saturation threshold) were flagged. Only those features with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of up to 2.6 in at least one channel and significant different from the local background (two-sided Student’s t-test <0.05) were used for further analysis.

The categorisation of the responsive genes into biological processes was analysed using Gene Ontology (GO) (http://www.geneontology.org) [33]. Within each significant category, the enrichment Re was determined by using the following equation: Re = (nf/n)/(Nf/N), where nf is the number of differential genes within the particular category, n is the total number of genes within the same category, Nf is the number of differential genes in the entire microarray, and N is the total number of genes in the microarray. The pathway analysis was carried out using the KEGG database [34]. A Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test and a Chi-square test were used to classify the GO category and pathway analysis. The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated to correct the p value. A p value <0.05 and FDR <0.05 were used as the threshold to select significant GO categories and KEGG pathways.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted to verify the reliability of the microarray. The qPCR experiments were assessed on the same pooled RNA extracts as the microarray. The RNA samples were reverse transcribed to cDNA using the PrimeScript™ reagent Kit (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers were designed to amplify sequences of 150–250 base pairs (bp), and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The cDNA samples were used for qRT-PCR analysis, which was performed using a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 31 s. Each sample was run in triplicate. The actin gene (Os11g0163100) was used as an internal control to normalise all data. After completion of the PCR amplification, the relative fold change after stimulation was calculated based on the 2−△△CT method [35].

Table 1.

Primers used in Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction to verify differentially expressed genes identified in the microarray experiment.

| Gene | Forward primer sequences(5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer sequences(5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Os02g0570400 | GTTGGTAGGGAGCACATCAGG | CCATTGGCAAGGGTTAGCATA |

| Os04g0178400 | CAACAAGAGCCCACAAGACCACG | ATCTCATACCCTCCGATTTCGCAG |

| Os05g0253200 | AACAACACCGTTTGCCACATTAC | TTGACCAACCACGTCCAACTTAT |

| Os05g0500900 | CGACACCTCGCCCATCCTCT | GCCGCTCCATCTCCTCCTCTAT |

| Os102g0416200 | ACCAGAGCTTCGGGTGCGTGAC | AAGCGGAGCTGCTCGGAGATGG |

| Os102g0542900 | GGCGACTTCTCCACCCTACTATG | CCAGAACCAGATGGCCGTCCTTG |

| Os03g0808000 | ACATGGCAGGGAGGGAGTGGATA | CGCATTTCTTAGCTGAGTCGCAGTAG |

| Os03g0658800 | CATTCCTGGCACCGCATTCTAC | TCTCACTGATTAAAGGCTTCTCC |

| Os08g0460000 | GTGAACGGGCTCGGTATCTC | CTGGTGTAGACGGTGTTGGAGG |

| Os12g0112000 | AACCTCACCTCCCTCTTCGA | AACCTGATTGCCTCCTCATCG |

| Os11g0163100 | CATCCTGCGTCTGGACCTTG | TTCCCGTTCAGCAGTGGTAG |

2.6. Statistical analysis

Biochemical and physiological data were analysed by ANOVA. LSD’s multiple comparison tests were conducted using SPSS software version 18.0. Expression analysis was initially carried out using Feature Extraction Software 10.7 from Agilent Technologies. Further analysis was performed using GeneSpring GX 10 and GenMAPP.

3. Results

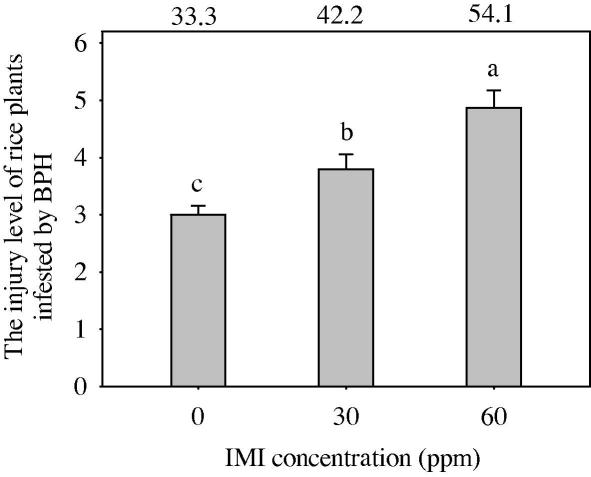

3.1. Effect of IMI on the level of injury of rice plants infested by BPH nymphs

Compared to the untreated control plants, IMI treatments significantly elevated the injury level of rice plants infested by BPH nymphs (F = 13.94, df = 2, 87, P = 0.0001) (Fig. 1). Multiple comparisons showed that the damage levels for 60 and 30 ppm IMI treatments were significantly greater than for control plants. The damage level for 60 ppm IMI was significantly greater than for the 30 ppm IMI treatment. In addition, the injury indices of rice plants treated with 30 and 60 ppm IMI increased by 26.7% and 62.2%, compared to controls, respectively, indicating that the rice plants treated with IMI are suitable for BPH feeding, or that IMI induced the susceptibility of rice to BPH infestation.

Fig. 1.

Effect of IMI on the injury level of rice plants infested by BPH. Numbers on the top correspond to the damage index under different IMI concentrations. Data are presented as the means ± SD. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level.

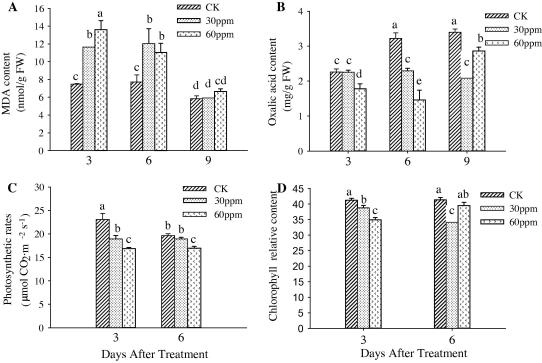

3.2. IMI-induced physiological and biochemical changes

An ANOVA analysis of the data presented in Fig. 2 confirmed that IMI significantly affected the amount of MAD, oxalic acid, chlorophyll, and the photosynthetic rate (F = 36.88; df = 8, 18; p < 0.01 for MAD; F = 53.8; df = 8, 18; p < 0.01 for oxalic acid; F = 24.39; df = 5, 12; p < 0.01 for chlorophyll; F = 33.67, df = 5, 12; p < 0.01 for the photosynthetic rate). Significantly greater amounts of MAD were present in the leaf blades treated with 30 and 60 ppm IMI at 3 and 6 DAF compared to the leaf blades of the control. The amount of MAD at 3 and 6 DAF increased by 68.6% and 49.3%, respectively. No significant differences in the amount of MAD at 9 DAF were found compared to control. However, the oxalic acid content of leaf sheaths at 3, 6 and 9 DAF was significantly lower than the oxalic acid content of the control samples. Additionally, the photosynthetic rates were lower and the chlorophyll content was smaller in leaves treated with IMI compared to the control. These findings support our model that IMI induces the susceptibility of rice to BPH infestation.

Fig. 2.

Effects of IMI on the physiology and biochemistry of rice plants. (A) MDA content, (B) Oxalic acid content, (C) Photosynthetic rates, (D) Relative content of chlorophyll. Data are presented as the means ± SD. The different letters above the bars indicate that the means of these values are significantly different at a 5 % level.

3.3. IMI-induced gene expression profile changes

Microarray results revealed that a total of 331 probe sets exhibited a ⩾2-fold or ⩽0.5-fold change in induction or suppression. Of these 331 probe sets, 142 were upregulated, and 189 were downregulated. A full list of the probe sets with significantly different fold change can be found in Table S1. Some genes were represented with more than one probe set. Therefore, the number of responsive probe sets is greater than the number of responsive genes. The 331 probe sets corresponded to 225 genes and these genes are presented in Tables S2. Of these 225 responsive genes, 117 were upregulated, and 108 were downregulated.

To verify the reliability of the microarray data, we selected 10 genes for analysis by qRT-PCR. We selected 5 up-regulated genes and 5 down-regulated genes that exhibited differential expression in the microarray. As shown in Fig. 3, the gene expression levels were consistent with microarray, and a positive correlation was detected between the from the 60 ppm IMI and qRT-PCR amplification (r2 = 0.904, Fig. 3). These qRT-PCR findings support the results of the microarray experiment.

Fig. 3.

Confirmation of the microarray results by qRT-PCR. Analysis by qRT-PCR of 10 genes selected from the IMI-responsive genes was performed with RNA extracted from control rice sheaths or 60 ppm IMI treated rice sheaths. The fold change of related genes after 60 ppm IMI treatment is presented on the left. The correlation between microarray signal ratios and qRT-PCR is presented on the right..

The differentially expressed genes were classified into different functional categories according to the Gene Ontology (GO) project. The GO categories and enrichment analysis results for the 225 genes are included in Table 2. A group of 171 genes were matched with GO term annotations in molecular function, oxidoreductase activity, structural component of cell walls, lipid, tetrapyrrole and neurotransmitter binding, signal transducer activity, and electron carrier activity. A group of 183 genes were involved in the enrichment of cellular components, protein complexes, vesicles, membranes, external encapsulating structures, and membrane parts. There were 170 genes with GO term annotations to biological processes, including the regulation of cellular processes, oxidation reduction, secondary metabolic processes, responses to endogenous and biotic stimuli, multicellular organismal development, cell growth, hormone metabolic processes, and responses to stress. The differentially expressed genes were classified into eight functional groups, and classification results are summarised in Table S3.

Table 2.

Gene ontology term enrichment analysis of genes with different expression patterns.

| GO Id | GO Term | Query item | Total | p value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular function | 171 | 17734 | |||

| GO:0016491 | Oxidoreductase activity | 29 | 1703 | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| GO:0005199 | Structural constituent of cell wall | 4 | 80 | 0.0084 | 0.0326 |

| GO:0008289 lipid binding | 12 | 3 | 50 | 0.0002 | 0.0044 |

| GO:0042165 | Neurotransmitter binding | 4 | 75 | 0.0068 | 0.0289 |

| GO:0046906 | Tetrapyrrole binding | 16 | 516 | 0.0001 | 0.0024 |

| GO:0009055 | Electron carrier activity | 15 | 793 | 0.0106 | 0.0348 |

| GO:0004871 | Signal transducer activity | 21 | 1310 | 0.0157 | 0.046 |

| Cellular Component | 183 | 18477 | |||

| GO:0043234 | Protein complex | 19 | 1085 | 0.0092 | 0.0341 |

| GO:0031982 | Vesicle | 67 | 3839 | 0 | 0 |

| GO:0016020 | Membrane | 82 | 6112 | 0.0004 | 0.0044 |

| GO:0030312 | External encapsulating structure | 24 | 1155 | 0.0004 | 0.0044 |

| GO:0044425 | Membrane part | 31 | 2120 | 0.0126 | 0.0399 |

| Biological Process | 170 | 0 15245 | |||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 18 | 790 | 0.0007 | 0.006 |

| GO:0042445 | Hormone metabolic process | 3 | 44 | 0.0101 | 0.0344 |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 20 | 1075 | 0.004 | 0.019 |

| GO:0007275 | Multicellular organismal development | 19 | 1154 | 0.0166 | 0.046 |

| GO:0016049 | Cell growth | 6 | 152 | 0.0041 | 0.019 |

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 59 | 4553 | 0.0076 | 0.0309 |

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 25 | 1414 | 0.0026 | 0.0154 |

| GO:0009719 | Response to endogenous stimulus | 30 | 1998 | 0.01 | 0.0344 |

| 3 GO:0050794 | Regulation of cellular process | 58 | 3928 | 0.0004 | 0.0044 |

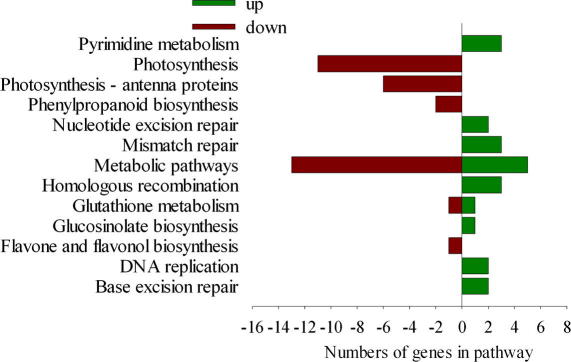

The KEGG pathway analysis for the differentially expressed genes showed that the genes are involved in base excision repair, DNA replication, flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, glucosinolate biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, homologous recombination, mismatch repair, nucleotide excision repair, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, photosynthesis-antenna proteins, photosynthesis, and pyrimidine metabolism (Table 3). The KEGG pathways analysis of the differentially expressed genes is summarised in Table S4.

Table 3.

Kegg pathway enrichment analysis of genes with different expression patterns.

| Pathway name | Query item | Total | p value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base excision repair | 2 | 35 | 0.0298 | 0.0109 |

| DNA replication | 2 | 37 | 0.0328 | 0.0109 |

| Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis | 1 | 3 | 0.0288 | 0.0109 |

| Glucosinolate biosynthesis | 1 | 3 | 0.02888 | 0.0109 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 2 | 45 | 0.0461 | 0.0118 |

| Homologous recombination | 3 | 24 | 0.001 | 0.0008 |

| Mismatch repair | 3 | 26 | 0.0012 | 0.0008 |

| Nucleotide excision repair | 2 | 44 | 0.0443 | 0.0118 |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 2 | 41 | 0.0392 | 0.0118 |

| Photosynthesis – antenna proteins | 6 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Photosynthesis | 11 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 3 | 82 | 0.0243 | 0.0109 |

4. Discussion

The physiology and biochemistry in rice plants treated with pesticides are significantly altered [18]. The present findings demonstrated that MAD content increased, but oxalic acid content and the photosynthetic rate decreased significantly following IMI application. These results are consistent with our previous findings [18]. The reduction of resistance of rice to insect pests due to physiological and biochemical changes in rice plants caused by pesticide applications is known as pesticide-induced susceptibility [6]. Pesticide-induced susceptibility of rice is an important phenomenon among the side effects of pesticides. The present experiment showed that IMI induced different expression levels of some stress response genes in rice plants, e.g. oxidoreductase activity genes, cytochrome P450 genes the terpene synthase gene, chitinase genes, the Gibberellin 20-oxidase gene, ethylene response proteins genes, pathogenesis-related protein genes, and other genes involved in signal transduction activity, electron carrier activity, substance transportation, and photosynthesis. Oxidoreductase activity is a key factor for many cell functions. It is necessary to prevent over-oxidation or over-reduction, both of which can cause serious damage to plant cells or cell death [36]. Cytochrome P450s are a large group of heme-containing enzymes, catalyse a considerable array of crucial reactions in plant primary and secondary metabolism. The present findings demonstrated 5 cytochrome P450 genes were induced by IMI and cytochrome P450 CYP99A1 (Os04g0178400) gene was especially up-regulated 27.5-fold and was significantly higher than that of the other 4 genes. Cytochrome P450 CYP99A gene encode cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase(C4H) in sorghum [37]and C4H was a feedback modulator at the entry point into the phenylpropanoid pathway [38]. Phenylpropanoid are involved in defense against wounding and herbivore/or pathogen attacks in many plants [39]. A previous study demonstrated that expression of the cytochrome P450 CYP99A1 gene of the salt tolerant Bala rice cultivar was down-regulated under arsenate stress [24]. In contrast, expression of the same gene in the susceptible cultivar (Azucena) was up-regulated under arsenate stress. Thus, we infer that up-regulated expression of cytochrome P450 CYP99A1 gene is a signal factor of IMI-induced rice susceptibility.

Of the 59 stress response genes that responded to IMI treatment, 30 were up-regulated, and 29 were down-regulated (Table S4). The maximum down-regulated expression level was that of the chitinase gene (Os10g0542900), which was down-regulated 4.8-fold, followed by germin-like protein 1 (Os08g0460000), which was down-regulated 3.3-fold. In general, the expression levels of down-regulated genes were in a lower range. However, the up-regulated genes were in a greater range of expression levels. For example, the terpene synthase gene (Os02g0570400) was up-regulated by 14.3-fold. Chitinases play an important role in the resistance of plants to pests [39] and chitinase activity in resistant cultivar is significantly higher than susceptible cultivar on day 3 after BPH infestation [40]. Therefore, we infer that the suppression of the expression of chitinase genes by IMI may be a factor in the insecticide-induced susceptibility of rice to BPH.

IMI induced significant changes to the expression of genes involved in signal transduction activity, electron carrier activity, substance transportation, and photosynthesis. Gibberellin 20-oxidase gene encoding a multifunctional enzyme involved in gibberellin biosynthesis [41] were down-regulated after IMI treatment. Gibberellin plays a vital regulation role in growth, development, the physiology and the biochemistry of the rice plant. Levels of plant hormones in rice treated with pesticides significantly decreased [21], indicating that the pesticides affected growth, development, and the vigour of the rice plants. Three ethylene response protein genes in ethylene signalling pathways were up-regulated, but four pathogenesis-related protein genes were down-regulated. These signalling pathways play important roles in growth, development, and resistance of plants [42,43]. IMI-induced susceptibility may be associated with changes to these signalling pathways. Lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) are highly conserved proteins in plants and play an important role in the resistance to pests, activation of resistance signalling, and adaptation to environmental stress [43]. Nine LTPs were differentially expressed, of which 7 genes (Os012g0115100, Os10g0551700, Os10g0552600, Os11g0116200, Os11g0427800, Os12g0114800, Os11g0115100) were down-regulated, and 2 (Os01g0822900, Os12g0114500) were up-regulated. These findings support the model that differentially expressed genes are associated with pesticide-induced susceptibility.

The current experiment revealed that 28 differentially expressed genes represented 12 different KEGG biological pathways. Genes involved in base excision repair, DNA replication, homologous recombination, and mismatch repair were up-regulated, and all these genes are related to the genomic repair process. The chlorophyll content and the photosynthetic rate of the rice leaves significantly declined following IMI application, which is consistent with significantly decreased expression of genes controlling photosynthetic rate and photosynthetic antenna proteins. In regards to metabolic pathways, IMI suppressed the photosynthetic system I and photosynthetic system II, electron transport chains, and genes involved in chlorophyll-protein complexes. The flavonol-3-O-methyltransferenase gene, which acts in the flavonoids and flavonol metabolic pathway, and the lignin peroxidase gene which acts in the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, were down-regulated following IMI treatment. Flavonoids and flavonols are important secondary metabolites in plants and play a role in defence against herbivores [44]. When interrupted flavonoid synthetic pathways, induced-resistance is suppressed in cucumber [45]. Flavonoids in rice plants are associated with resistance of rice to BPH [46].Therefore, we considered that flavonol-3-O-methyltransferenase gene may influence the synthesis of flavonoid and indirectly results in the susceptibility. Phenylpropanoid compounds encompass a wide range of structural classes and biological functions. In phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, lignin peroxidase gene (Os11g0112400) which participate in synthesis of p-hydroxypheny lignin, guaiacyl lignin, 5-hydroxygualacyl lignin, and syringyl lignin were down-regulated (KEGG Pathway see http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg2.html). Rice lignin is a mixed p-hydroxyphenyl-guaiacyl-syringyl lignin[40]which. composes the secondary cell wall and is related to resistance to pests [47]. Thus the down-regulated expression of the lignin peroxidase gene may be associated with IMI-induced decline of rice resistance. Os03g0283200 gene encoding IN2-1 protein was down-regulated following IMI treatment. IN2-1 protein have glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity and plays an important role in pesticide detoxification and resistance to stress [47,48]. It has been demonstrated that overexpression of GST enhance the resistance of GM plants to stress [49]. Therefore, the down-regulated expression of GST gene following IMI treatment may decline the resistance of rice to exogenous stress.

In addition, IMI-induced susceptibility does not involve in single gene or single metabolic pathway but in multiple genes or multiple pathways, such as cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase, chitinaselignin peroxidase, flavonoids and flavonol metabolic pathway, phenylpropanoid metabolic. The identification of differentially expressed genes could provide useful information for the further study of the molecular mechanism of IMI-induced susceptibility of rice to BPH infestation.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded in part by National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2010CB126200) and by the National Natural Science Fund of China (No. 30870393).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Chelliah S., Heindrichs E.A. Factors affecting insecticide-induced resurgence of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens on rice. Environ. Entmol. 1980;9:773–777. [Google Scholar]

- 2.G.C. Jahn, J.A. Litsinger, Y. Chen, A. Barrion. Integrated Pest Management of Rice: Ecological Concepts. In Ecologically Based Integrated Pest Management (eds. O Koul and GW Cuperus). CAB International (2007) 315–366.

- 3.Croft B.D., Brown A.W.A. Responses of arthropod natural enemies to insecticides. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1975;20:285–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.20.010175.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preap V., Zalucki M.P., Jahn G.C. Brown planthopper outbreaks and management. Cambodian J. Agri. 2006;7(1):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L.P., Shen J., Ge L.Q., Wu J.C., Yang G.Q., Jahn G.C. Insecticide-induced increase in the protein content of male accessory glands and its effect on the fecundity of females in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) Crop Prot. 2010;29:1280–1285. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu J.C., Xu J.X., Yuan S.Z., Liu J.L., Jiang Y.H., Xu J.F. Pesticide-induced susceptibility of rice to brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2001;100:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinrichs E.A., Mochida A. From secondary to major pest status: the case of insecticide-induced rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, resurgence. Prot. Ecol. 1984;1:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sangha J.S., Chen Y.H., Palchamy K., Jahn G.C., Maheswaran M., Candida B., Adalla B., Leung H. Categories and Inheritance of Resistance to Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) in Mutants of indica Rice ‘IR64’. J. Econ. Entomol. 2008;101(2):575–583. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[575:caiort]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preap V., Zalucki M.P., Nesbitt H.J., Jahn G.C. Effect of fertilizer, pesticide treatment, and plant variety on realized fecundity and survival rates of Nilaparvata lugens (Stål); Generating Outbreaks in Cambodia. J. Asia Pacific Entomol. 2001;4(1):75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin K.M., He Y.X., Gan D.Y., Weng Q.Y. The effects of two rice resistant sources and their new breeding varieties on the biological characters of brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) Entomol. J. East China. 1995;4:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao S.G., Cheng X.N., Zhang X.X. Effects of nine rice varieties on survival and oviposition of Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) J. Nanjing Agri. Uni. 2000;23:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagata T., Kamimuro T., Wang Y., Han S., Noor N.M. Recent status of insecticide resistance of long-distance migrating rice planthoppers monitored in Japan, China and Malaysia. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 2002;5:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumura M., Takeuchi H., Satoh M., Sanada-Morimura S., Otuka A., Watanabe T., Van Thanh D. Species-specific insecticide resistance to imidacloprid and fipronil in the rice planthoppers Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera in East and South-east Asia. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008;64:1115–1121. doi: 10.1002/ps.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeschke P., Nauen R., Schindler M., Elbert A. Overview of the Status and Global Strategy for Neonicotinoids. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2011;59(7):2897–2908. doi: 10.1021/jf101303g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauen R., Denholm I. Resistance of insect pests to neonicotinoid insecticides: current status and future prospects. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2005;58:200–215. doi: 10.1002/arch.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z.W., Han Z.J., Wang Y.C., Zhang L.C., Zhang H.W., Liu C.J. Selection for imidacloprid resistance in Nilaparvata lugens: cross-resistance patterns and possible mechanisms. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003;59:1355–1359. doi: 10.1002/ps.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z.W., Han Z.J. Fitness costs of laboratory-selected imidacloprid resistance in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål. Pest Manag. Sci. 2006;62:279–282. doi: 10.1002/ps.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J.C., Xu J.F., Feng X.M., Liu J.L., Qiu H.M., Luo S.S. Impacts of pesticides on physiology and biochemistry of rice. Sci. Agri. Sin. 2003;36:536–541. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang A.H., Wu J.C., Yu Y.S., Liu J.L., Yue J.F., Wang M.Y. Selective insecticide-induced stimulation on fecundity and biochemical changes in Tryporyza incertulas (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2005;98:1144–1149. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-98.4.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu H.M., Wu J.C., Yang G.Q., Dong B., Li D.H. Changes in the uptake function of the rice root to nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium under brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) (Homoptera: Delphacidae) and pesticide stresses, and effect of pesticides on rice-grain filling in field. Crop Prot. 2004;23:1041–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu Z.H., Wu J.C., Dong B., Li D.H., Gu H.N. Two-way effect of pesticides on zeatin riboside content in both rice leaves and roots. Crop Prot. 2004;23:1131–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez C., Soto M., Restrepo S., Piegu B., Cooke R., Delseny M., Tohme J., Verdier V. Gene expression profile in response to Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. manihotis infection in cassava using a cDNA microarray. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;57:393–410. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-7819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J. Zhao, L. Buchwaldt, S.R. RIMMER, A. Sharpe, L. McGregor, D. Bekkaoui, D. Hegedus, Patterns of differential gene expression in Brassica napus cultivars infected with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Mol. Plant Pathol. 10 (2009) 635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Norton G.J., Lou-Hing D.E., Meharg A.A., Price A.H. Rice-arsenate interactions in hydroponics: whole genome transcriptional analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:2267–2276. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coram T.E., Pang E.C.K. Transcriptional profiling of chickpea genes differentially regulated by salicylic acid, methyl jasmonate and aminocyclopropane carboxylic acid to reveal pathways of defence-related gene regulation. Funct. Plant Biol. 2007;34:52–64. doi: 10.1071/FP06250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J.C., Qiu H.M., Yang G.Q., Liu J.L., Liu G.J., Wilkins R. Effective duration of pesticide-induced susceptibility of rice to brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål, Homoptera: Delphacidae), and physiological and biochemical changes in rice plants following pesticide application. Inter. J. Pest Manag. 2004;50:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IRRI (International Rice Research Institute). Standard evaluation system for rice (1988). 3rd Ed., IRRI, Philippines.

- 28.Liu Y.Q., Jiang L., Sun L.H., Wang C.M., Zhai H.Q., Wan J.M. Changes in some defensive enzyme activity induced by the piercing-sucking of brown planthopper in rice. J. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 2005;31(6):643–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.T. Yoshihara, K. Sogawa, M.D. Pathak, B.O. Juliano BO, S. Sakamura, Oxalic acid as a sucking inhibitor of the brown planthopper in rice (Delphacidae, Homoptera), Entomol. Exp. Appl. 27 (1980) 149–155.

- 30.Watanabe T., Kitagawa H. Photosynthesis and translocation of assimilates in rice plants following phloem feeding by the planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Homoptera: Delphacidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2000;93:1192–1198. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-93.4.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sofo A., Dichio B., Xiloyannis C., Masia A. Effects of different irradiance levels on some antioxidant enzymes and on malondialdehyde content during rewatering in olive tree. Plant Sci. 2004;166:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnon D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogata H., Goto S., Sato K., Fujibuchi W., Bono H., Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-[Delta][Delta] CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietz K.J. Redox control, redox signaling, and redox homeostasis in plant cells. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2003;228:141–193. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)28004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi X., Bakht S., Qin B., Leggett M., Hemmings A., Mellon F., Eagles J., Werck-Reichhart D., Schaller H., Lesot A. A different function for a member of an ancient and highly conserved cytochrome P450 family: From essential sterols to plant defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18848–18853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida K., Kaothien P., Matsui T., Kawaoka A., Shinmyo A. Molecular biology and application of plant peroxidase genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2003;60:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nitzsche W. Chitinase as a possible resistance factor for higher plants. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1983;65:171–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00264887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alagar M., Suresh S., Samiyappan R., Saravanakumar D. Reaction of resistant and susceptible rice genotypes against brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) Phytoparasitica. 2007;35:346–356. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olszewski N., Sun T., Gubler F. Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell. 2002;14:61–80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruce T.J.A., Pickett J.A. Plant defence signalling induced by biotic attacks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007;10:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kader J.C. Lipid-transfer proteins: a puzzling family of plant proteins. Trends. Plant Sci. 1997;2:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmonds M.S.J. Flavonoid-insect interactions: recent advances in our knowledge. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fofana B., Benhamou N., McNally D.J., Labbé C., Séguin A., Bélanger R.R. Suppression of induced resistance in cucumber through disruption of the flavonoid pathway. Phytopathology. 2005;95:114–123. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang G., Zhang W., Lian B., Gu L., Zhou Q., Liu T.X. Insecticidal effects of extracts from two rice varieties to brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999;25:1843–1853. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pedersen J.F., Vogel K.P., Funnell D.L. Impact of reduced lignin on plant fitness. Crop Sci. 2005;45:812–819. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edwards R., Dixon D.P., Walbot V. Plant glutathione S-transferases: enzymes with multiple functions in sickness and in health. Trends. Plant Sci. 2000;5:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu T., Li Y.S., Chen X.F., Hu J., Chang X., Zhu Y.G. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing cotton glutathione S-transferase (GST) show enhanced resistance to methyl viologen. J. Plant Physiol. 2003;160:1305–1311. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.