Abstract

Objective

Men who have sex with men (MSM) have higher rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) than women and heterosexual men. This elevated risk persists across age groups and reflects biological and behavioral factors, yet there have been few direct comparisons of sexual behavior patterns between these populations.

Methods

We compared sexual behavior patterns of MSM and male and female heterosexuals aged 18–39 using 4 population-based random digit dialing surveys. A 1996–1998 survey in 4 U.S. cities and 2 Seattle surveys (2003, 2006) provided estimates for MSM; a 2003–2004 Seattle survey provided data about heterosexual men and women.

Results

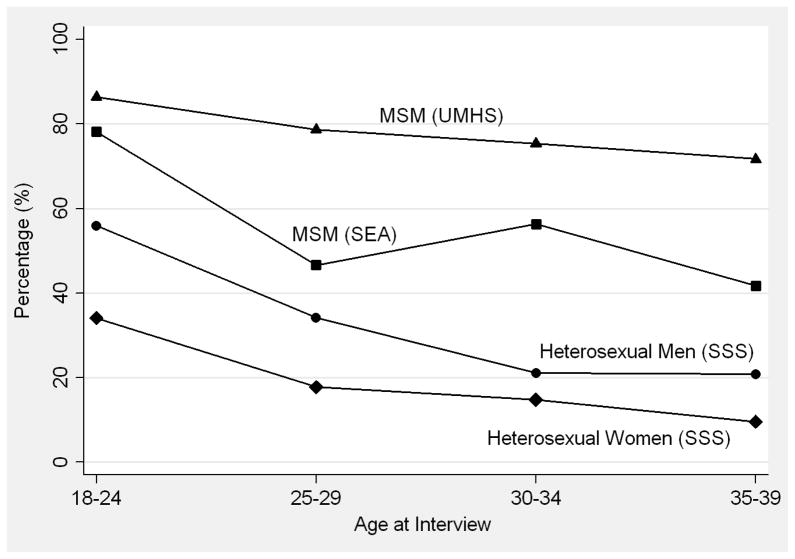

Sexual debut occurred earlier among MSM than heterosexuals. MSM reported longer cumulative lifetime periods of new partner acquisition than heterosexuals, and a more gradual decline in new partnership formation with age. Among MSM, 86% of 18–24 year olds and 72% of 35–39 year olds formed a new partnership during the prior year, compared to 56% of heterosexual men and 34% of women at ages 18–24, and 21% and 10%, respectively, at ages 35–39. MSM were also more likely to choose partners >5 years older and were 2–3 times as likely as heterosexuals to report recent concurrent partnerships. MSM reported more consistent condom use during anal sex than heterosexuals reported during vaginal sex.

Conclusions

MSM have longer periods of partnership acquisition, a higher prevalence of partnership concurrency, and more age-disassortative mixing than heterosexuals. These factors likely help explain higher HIV/STI rates among MSM, despite higher levels of condom use.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, heterosexuals, sexual behavior, HIV, STI

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) disproportionately affect men who have sex with men (MSM). MSM comprise approximately 2% of the U.S. population1, but accounted for 59% of new HIV infections and 62% of cases of early syphilis in 20092,3. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that HIV and early syphilis rates among MSM are >40 times higher than those among heterosexuals4. In part, these differences reflect the fact that an individual MSM can engage in both insertive and receptive sexual roles (i.e., versatility), while exclusively heterosexual men and women each engage in only one of these roles. Goodreau et al. demonstrated that an MSM population with a very high level of versatility would have a higher HIV prevalence than one with less versatility5. Furthermore, the transmission probability of HIV associated with anal sex is higher than that associated with vaginal sex6,7. These factors alone would result in significant disparities in HIV rates between MSM and heterosexuals even if both populations had similar numbers of sex partners, frequency of sex, and condom use levels8.

However, the sexual behaviors of MSM and of male and female heterosexuals are substantially different in ways that are not explained by biology alone. Prior research has found that MSM tend to have higher numbers of sex partners than heterosexuals9, but the dynamics of partnership formation10, concurrency11, and age mixing patterns12–14 have not been extensively characterized. These factors likely play important roles in the epidemiology of HIV/STI and in explaining observed disparities. While some of these behaviors have been assessed to better understand observed racial disparities in HIV/STI rates15–18, much less has been done to compare the behaviors of MSM and heterosexuals9,19. In this paper we used population-based studies to compare the sexual behaviors of MSM and heterosexual men and women in the U.S., paying particular attention to how patterns of behavior differed across age groups.

Methods

Study populations, study designs, and survey instruments

We used data from 4 random digit dialing (RDD) surveys (Table 1). To calculate sexual behavior estimates for MSM, we used the Urban Men’s Health Study (UMHS)20–22 and two Seattle surveys (SEA)23. For similar estimates among heterosexual men and women, we used data from the Seattle Sex Survey 2 (SSS)24.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the random digit dialing surveys; Seattle Sex Survey (2003–2004), Urban Men’s Health Study (1996–1998), and Seattle Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) RDD (2003 and 2006).

| Seattle Sex Survey [SSS] (Heterosexual Men & Women) | Urban Men’s Health Study [UMHS] (MSM) | Seattle MSM RDD [SEA] (MSM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 2003–2004 | 1996–1998 | 2003 & 2006 |

| Eligibility criteria |

|

|

|

| Sample size | N=1,194 (Heterosexuals, n=926) | N=2,881 (Age<40, n=1,621) | N=800 (Age<40, n=342) |

| Response rate | 24% | not reported | 46% (2003) & 22% (2006) |

| Cooperation rate | 46% | 78% | 97% (2003) & 87% (2006) |

| Partner-specific questions | Asked about up to 5 most recent partners (vaginal, oral, or anal sex) | Asked about up to 4 most recent male partners in the past year (any kind of sex) | Asked about up to 3 most recent male anal sex partners in the past year |

The SSS and the two SEA RDDs were conducted in the mid-2000s, while the UMHS, which enrolled MSM from 4 U.S. cities, was conducted from 1996–1998. For this analysis, we excluded SSS participants who had never had sex or reported partnerships that were not exclusively heterosexual. For UHMS and SEA, telephone numbers were sampled from zip codes with high proportions of MSM. Men who reported same-sex sexual behavior since age 14 were eligible. UMHS MSM were also eligible if they self-identified as homosexual, gay, or bisexual. Oral informed consent was obtained from all participants. To increase comparability across all surveys, we restricted analyses to participants aged 18–39 years.

Only SSS and SEA provided response rates, which were <50% and computed by dividing the number of interviews by an estimate of the number of eligible individuals from the RDD sampling frame. This denominator was the sum of the number of interviews, refusals, and an estimate of the number of eligible individuals among those for whom eligibility could not be determined25. The cooperation rates were based on the proportion of eligible individuals who opted to participate and were higher for UMHS and SEA (78–97%) than the SSS (46%). The UMHS and SEA surveys gathered partner-specific data only for partners in the past year. Thus, analyses regarding a participant’s most recent partner were restricted to heterosexual participants reporting at least one opposite-sex partner in the past year, and to MSM reporting at least one male partner in the past year. For partner-specific measures among MSM, UMHS data reflected participants’ most recent male partners while the SEA data included only male anal sex partners.

Measures

We chose sexual behavior measures that we hypothesized a priori might help explain differences in HIV/STI rates between MSM and heterosexual men and women. Although the exact wording of questions varied across surveys, most measures were similar. The Appendix includes specific survey questions and more detailed descriptions of each measure.

Age at sexual debut and number of partners

We calculated age at sexual debut with any partner among heterosexuals and UMHS MSM. (SEA MSM did not provide these data.) Among MSM only, we also compared age at sexual debut with a male partner and the age at anal sex debut. The SSS and UMHS provided data on lifetime number of partners, while all surveys included a question about number of partners in the past year.

Partnership formation and the cessation of new partner recruitment

We used partner-specific start and end dates (month and year) to estimate the time since the start of each participant’s most recently formed partnership. Using these data, we calculated the proportion of participants who had formed any new partnership in the past year. We defined the cessation of new partner recruitment as having last formed a new partnership >5 years ago. To estimate an individual’s total time of active partner-seeking to date, we calculated the number of years between a participant’s age at sexual debut and age at the start of the most recently formed partnership. Finally, we used the variable regarding number of partners in the past year to indicate if an individual had engaged in any sex in the past year.

Mixing by age

We used age data about each participant’s most recent partner to calculate the proportion who had partners with greater than a 5- or 10-year age difference.

Condom use

Across all surveys, we assessed whether or not participants always used condoms with their most recent partner. This was based upon partner-specific questions about how often condoms were used, or by comparing the total number of sex acts with the number of protected sex acts. As a proxy for partner type, we stratified these findings by partnership duration (≤3 or >3 months).

Sex partner concurrency

Using available partnership start and end dates (month and year), we determined the proportion of respondents who reported any overlapping partnerships in the past year. We classified participants with no partners in the past year as having no partner concurrency.

Partner meeting place

Using a question about how respondents met their most recent partner, we created three categories26: through formal social venues (e.g., friends, family, work, private party), through less formal social venues (e.g., bar, Internet, bath house, park), or by other means (i.e., participant chose the “other” option).

Statistical methods

We compared each measure among heterosexual men and women and MSM using descriptive statistics. As appropriate, we used t-tests, chi-square tests, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to assess for group differences, and linear and logistic regression to test for age trends. Although UMHS did include sampling weights, the SSS and SEA did not. Because we found no meaningful differences between the weighted and unweighted estimates in our analysis of UMHS data, we elected to apply a uniform analytic approach across datasets and all presented estimates are unweighted. Therefore, in the context of these study designs, p-values are best understood as a metric for comparing the strength of the observed associations within each study. We conducted all analyses using Intercooled Stata 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Study procedures were either exempt from IRB review (UMHS and SEA) or approved (SSS) by the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington.

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of participants included in this analysis was similar across surveys, ranging from 30.0–32.1 years. In all surveys, approximately three-quarters of participants were non-Hispanic white and two-thirds had obtained a 4-year college degree. Among MSM, 15.7% of UMHS participants and 10.1% of SEA participants reported being HIV-infected; no heterosexual participants reported HIV infection.

Age at sexual debut and number of partners

The mean age at same-sex sexual debut was 16.5 years among UMHS MSM and 17.0 years among SEA MSM (Table 2). Approximately one-quarter of UMHS MSM first had sex with a woman; when this was considered, the overall age at sexual debut among UMHS MSM was 15.4 years. Heterosexual debut was older at 17.4 years for men and 17.8 years for women. Anal sex debut among MSM was several years later than overall age of sexual debut, at 19.6 years in UMHS and 20.2 years in SEA.

Table 2.

Age-specific sexual behavior patterns of men who have sex with men (MSM) and heterosexual participants in three random digit dialing surveys; Seattle Sex Survey (SSS, 2003–2004), Urban Men’s Health Study (UMHS, 1996–1998), and Seattle MSM RDD (SEA, 2003 and 2006).

| Characteristic | Population/Survey | Age at interview | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 n=344 mean (95% CI) |

25–29 n=703 mean (95% CI) |

30–34 n=940 mean (95% CI) |

35–39 n=902 mean (95% CI) |

Overall n=2889 mean (95% CI) |

||

| Age at sexual debut | Heterosexual men | 16.7 (16.2–17.2) | 17.2 (16.7–17.7) | 17.6 (17.1–18.1) | 17.9 (17.3–18.5) | 17.4 (17.1–17.7) |

| Heterosexual women | 17.3 (16.8–17.7) | 18.0 (17.5–18.5) | 17.9 (17.4–18.3) | 18.1 (17.5–18.6) | 17.8 (17.6–18.1) | |

| MSM (UMHS) | 15.3 (14.8–15.9) | 15.5 (15.1–16.0) | 15.4 (15.0–15.7) | 15.4 (15.0–15.8) | 15.4 (15.2–15.6) | |

| MSM (SEA) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Age at male sexual debut | MSM (UMHS) | 16.4 (15.8–17.0) | 16.9 (16.3–17.4) | 16.5 (16.0–16.9) | 16.3 (15.8–16.7) | 16.5 (16.2–16.7) |

| MSM (SEA) | 16.8 (15.0–18.6) | 18.8 (17.3–20.3) | 16.7 (14.8–18.5) | 16.5 (15.0–18.1) | 17.0 (16.1–17.9) | |

| Age at anal sex debut | MSM (UMHS) | 18.2 (17.7–18.7) | 19.7 (19.3–20.1) | 19.7 (19.3–20.1) | 19.8 (19.4–20.3) | 19.6 (19.4–19.8) |

| MSM (SEA)* | 18.2 (16.1–20.3) | 20.2 (18.8–21.6) | 19.1 (17.4–20.8) | 21.1 (19.5–22.8) | 20.2 (19.2–21.1) | |

| Number of partners, last year [median, range] | Heterosexual men | 1 (0–99) | 1 (0–9) | 1 (0–10) | 1 (0–10) | 1 (0–99) |

| Heterosexual women | 1 (0–5) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–7) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–7) | |

| MSM (UMHS) | 4 (0–200) | 4 (0–200) | 4 (0–500) | 4 (0–400) | 4 (0–500) | |

| MSM (SEA)* | 3 (0–40) | 2 (0–35) | 3 (0–300) | 2 (0–50) | 2 (0–300) | |

| Number of partners, lifetime [median, range] | Heterosexual men | 4 (1–99) | 8 (1–99) | 9 (1–99) | 12 (1–99) | 8 (1–99) |

| Heterosexual women | 4 (1–25) | 6 (1–60) | 7 (1–40) | 7 (1–99) | 6 (1–99) | |

| MSM (UMHS) | 15 (1–3100) | 30 (1–2562) | 55 (1–7000) | 67 (0–9005) | 45 (0–9005) | |

| MSM (SEA) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Age of most recent partner was >5 years older or younger^ [%] | Heterosexual men | 7.9 (0.0–16.9) | 18.0 (5.3–30.6) | 45.5 (22.9–68.1) | 23.8 (3.9–43.7) | 20.8 (13.5–28.2) |

| Heterosexual women | 10.0 (0.0–21.4) | 42.3 (22.0–62.7) | 45.5 (22.9–68.1) | 18.2 (0.0–45.4) | 29.2 (19.6–38.8) | |

| MSM (UMHS) | 42.5 (33.5–51.5) | 37.9 (32.2–43.7) | 35.9 (31.2–40.6) | 43.0 (37.8–48.2) | 39.2 (36.4–42.0) | |

| MSM (SEA)† | 52.0 (31.0–73.0) | 44.1 (26.5–61.7) | 53.7 (40.0–67.4) | 44.8 (31.6–58.0) | 48.5 (41.0–56.1) | |

| Any concurrency in the last year** [%] | Heterosexual men | 13.9 (5.7–22.1) | 12.7 (6.6–18.8) | 7.7 (2.8–12.6) | 5.8 (1.2–10.3) | 9.7 (6.9–12.6) |

| Heterosexual women | 13.2 (6.1–20.3) | 8.7 (4.1–13.3) | 5.0 (1.6–8.4) | 4.9 (1.0–8.8) | 7.5 (5.2–9.7) | |

| MSM (UMHS) | 23.3 (16.5–30.2) | 31.6 (26.8–36.4) | 32.3 (28.4–36.2) | 32.3 (28.4–36.3) | 31.3 (29.1–33.6) | |

| MSM (SEA)† | 12.5 (0.4–24.6) | 12.3 (4.6–20.1) | 20.6 (12.4–28.8) | 20.0 (13.3–26.7) | 17.8 (13.8–21.9) | |

Male partners only.

Restricted to partners formed within the last year.

Anal sex partners only.

Includes those who reported no sex partners in the past year.

At all ages, heterosexual men and women reported a median of 1 partner in the past year, while MSM reported a median of 4 partners in UMHS and 2–3 male partners in SEA. MSM reported significantly more lifetime partners than heterosexual men and women at all ages (p<0.01 for each age group). The median lifetime number of sex partners among those aged 18–24 was 4 in heterosexuals and 15 in UMHS MSM, and among persons age 35–39, was 10 and 67, respectively. (The SEA did not ask about lifetime number of partners.)

Partnership formation and the cessation of new partner recruitment

Across all age groups, MSM were more likely than heterosexuals to report having a new partner in the past year (Figure 1a). Among UMHS MSM, 86.4% of the youngest MSM (age 18–24) and 71.7% of the oldest MSM (age 35–39) formed a new same-sex partnership in the prior year. These proportions were lower among SEA MSM – due, in part, to the fact that only male anal sex partners were counted – with 78.1% of the youngest MSM and 41.7% of the oldest MSM reporting a new male anal sex partnership in the past year. Among heterosexuals, the proportions were lower than in any of the MSM surveys, particularly among participants in their 30s. For example, 55.9% of the youngest men and 20.8% of the oldest men formed a new partnership in the prior year, compared with 34.1% of the youngest women and 9.6% of the oldest women.

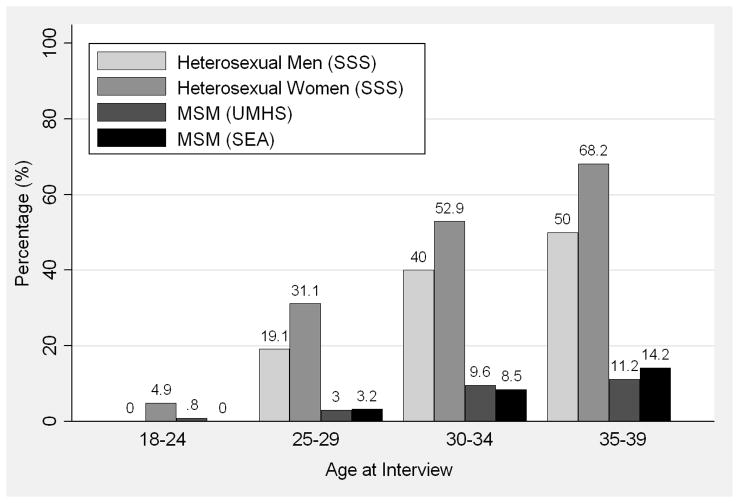

Figure 1.

(A) Proportion of men who have sex with men (MSM) and heterosexual men and women who formed a new partnership in the past year by age at interview; (B) Proportion of MSM and heterosexual men and women whose last new partnership began more than 5 years ago by age at interview; Seattle Sex Survey (SSS, 2003–2004), Urban Men’s Health Study (UMHS, 1996–1998), and Seattle MSM RDD (SEA, 2003 and 2006).

These trends are clearly seen when viewed over a 5-year period: a much higher proportion of heterosexuals than MSM reported that their last new partnership began >5 years ago (Figure 1b). For example, among participants aged 35–39, 50.0% of heterosexual men and 68.2% of heterosexual women reported that at least 5 years had passed since the start of their most recent partnership. Only 11.2% of UMHS MSM and 14.2% of SEA MSM in the same age range reported this. Consequently, MSM in each age group reported longer periods of new partner acquisition than heterosexuals, defined as the amount of time from sexual debut to the start of the most recently formed partnership. Because the age-specific means for heterosexual men and women, and MSM in both surveys, were so similar (within 1–3 years), we combined the data for these respective groups. Among participants ages 35–39, MSM reported an average of 20.2 years of new partner acquisition compared with 11.9 years among heterosexuals. This difference between heterosexuals and MSM increased linearly with age (p<0.01 for interaction).

At the same time, the proportion of individuals who reported no sexual activity may be higher among older MSM than among their heterosexual counterparts, though these findings were not consistent across surveys. Unlike UMHS MSM and heterosexuals, the proportion of SEA MSM who reported no male partner in the past year increased linearly by age, including nearly a quarter (23.0%) of those age 35–39 (p<0.01 for trend). This proportion was approximately four times higher than that observed among Seattle heterosexual men (4.8%) and women (6.7%) in the same age group (SEA MSM vs. heterosexual men and women, p<0.01).

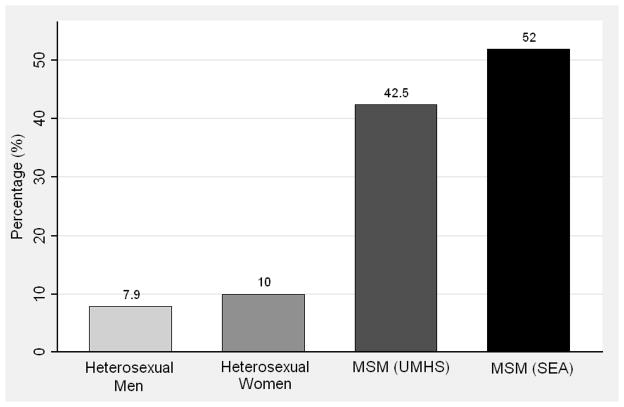

Mixing by age

To accurately capture partnerships formed at a given age, we restricted these analyses to participants reporting a new partnership in the past year. Among all 18–24 year olds, there were no recent partners who were >5 years younger. Over one-half (52.0%) of SEA MSM aged 18–24 reported a recent male anal sex partner who was >5 years older, while 42.5% of UMHS MSM reported this age difference with a recent male partner (Figure 2a). By contrast, only 7.9% of heterosexual men and 10.0% of heterosexual women in this age group reported a recent partner who was >5 years older (MSM vs. heterosexual men and women, p<0.01). No heterosexuals age 18–24 reported a recent partner with a 10-year age difference, while 16.7% of UMHS MSM and 28.0% of SEA MSM reported this (MSM vs. heterosexual men and women, p<0.001). At older ages, the difference in the proportion of MSM and heterosexuals reporting a 5-year age difference with their most recent partner was less apparent (Table 2), although MSM age 35–39 were more likely than heterosexuals to report a 5-year age difference with their most recent partner (p=0.018).

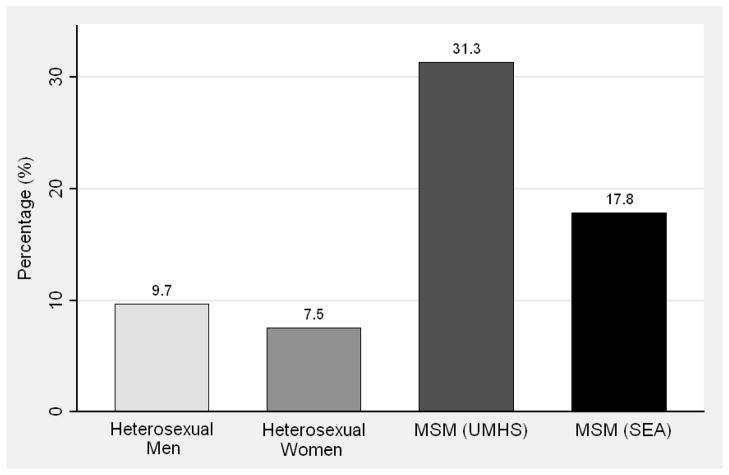

Figure 2.

(A) Proportion of men who have sex with men (MSM) and heterosexual men and women age 18 to 24 years who reported that their most recent partner was >5 years older or younger; (B) Proportion of MSM and heterosexual men and women who reported any concurrent (overlapping) partnerships in the past year; Seattle Sex Survey (SSS, 2003–2004), Urban Men’s Health Study (UMHS, 1996–1998), and Seattle MSM RDD (SEA, 2003 and 2006).

Condom use

Among recent partnerships lasting ≤3 months, approximately 80% of MSM in UMHS reported always using condoms during insertive anal sex. A similar proportion reported this during receptive anal sex. By contrast, only 57.4% of heterosexual men and 44.4% of heterosexual women reported consistent condom use during vaginal sex in partnerships of ≤3 months. For partnerships lasting >3 months, consistent condom use was reported by 48.0% and 46.8% of MSM during insertive and receptive anal sex, respectively, and by less than one-quarter of heterosexual men (23.8%) and women (19.7%). (Due to small cell sizes, we could not estimate position-specific (insertive and receptive) condom use among SEA MSM.)

Concurrency

As shown in Figure 2b, the prevalence of sex partner concurrency during the year was much lower among heterosexual men and women (9.7% and 7.5%, respectively) than among UMHS MSM (31.3%) and SEA MSM (17.8%) (MSM vs. heterosexual men and women, p<0.01). The prevalence of partner concurrency declined linearly with age among heterosexual men (p=0.03) and women (p=0.01). The prevalence of concurrency increased with age among MSM, though this trend was not statistically significant in either UMHS (p=0.11) or SEA (p=0.14) (Table 2).

Meeting new partners

Over three-quarters of heterosexual men (75.3%) and women (76.5%) met their most recent partner through a formal social venue (e.g., friends, family, work, school) compared with 32.9% of UMHS MSM and 30.3% of SEA-RDD MSM (p<0.001). MSM more often reported meeting partners through less formal social venues (e.g., bars, Internet, street). Among women and UMHS MSM, the proportion who met their most recent partner through formal social venues was lower among older age groups than younger age groups.

Discussion

We used data from several large population-based surveys to estimate the dynamics of sexual partnership formation, concurrency, and age mixing among MSM and heterosexuals. MSM initiated sexual activity at slightly younger ages than heterosexuals, reported larger numbers of recent partners, continued to form new partnerships later into adulthood, and displayed more age-disassortative mixing and sex partner concurrency. Along with biological factors, these sexual behavior patterns likely help explain the high HIV/STI rates among MSM. However, compared with heterosexuals, MSM used condoms more frequently and a larger proportion of MSM may become sexually abstinent in their 30s.

Our findings are most notable for demonstrating how partnership formation patterns differed between MSM and heterosexuals from time of sexual debut through their 30s. Approximately half of sexually active heterosexuals surveyed were effectively out of the risk pool for HIV/STI by age 30, as they reported no new partners during the prior 5 years. By contrast, a much higher proportion of MSM continued to form new partnerships well into their 30s. This is consistent with Australian HIV data that suggested that the formation rate among MSM peaks in the mid-30s27. Our study suggests that the average period of new partnership acquisition among MSM is at least twice as long as among heterosexuals. Indeed, mathematical models estimated that the mean age of HIV acquisition among Australian MSM is in the mid-30s27, and researchers in the UK found that HIV incidence was highest among MSM in this age group28, an age when most heterosexuals are no longer forming new partnerships.

The epidemiologic implications of sustained new partnership formation among MSM are likely magnified by the relatively high frequencies of disassortative age mixing observed among MSM compared to heterosexuals. For example, because HIV prevalence rises with age, younger MSM who have older partners are at increased risk for exposure to HIV infection12,29,30.

Mathematical models suggest that sex partner concurrency amplifies the spread of HIV through sexual networks11. We found that the prevalence of concurrent partnerships in the past year was several-fold higher among MSM than heterosexuals, and that, unlike among heterosexuals, the prevalence of concurrency did not decline with age. Data from other population-based studies have consistently found a higher prevalence of concurrency among heterosexual men than among women31–33. We also observed some gender asymmetry in the prevalence of concurrency among heterosexuals - slightly higher rates of concurrency for heterosexual men than women - which leads to small fragmented components (e.g., a man with two female partners) and reduces the impact that concurrency has on the connectivity of the network34. Among MSM practicing both insertive and receptive anal sex, however, concurrency may be more likely to be symmetric, which could lead to the rapid growth of larger connected network components and more efficient HIV/STI transmission within the network.

MSM overall reported both higher numbers of partners and more concurrency than heterosexuals. In a descriptive study like this it is not possible to tease apart the relative impact of these two factors. Both likely contribute to greater transmission. It is possible that the high rates of partner acquisition among MSM are sufficient to produce and sustain the observed disparities in HIV/STI prevalence. But it is also possible that concurrency produces a qualitative difference in transmission dynamics even in this context – creating more robust connectivity in the network, compounded by the window of high infectivity during acute infection. This qualitative effect has been shown in two recent modeling studies of heterosexual spread of HIV in Zimbabwe35,36, and a similar modeling study would be needed here to identify the independent and joint impacts of concurrency and rapid partner acquisition.

This study had several limitations. First, we used three different surveys which limited the comparability of measures between groups. To our knowledge, however, no single survey includes large numbers of MSM and heterosexuals from rigorously sampled representative populations as well as the parameters we sought to study. The Seattle-based heterosexual and MSM RDDs were all conducted in the mid-2000s, and our findings using the SEA survey were similar to what Levin et al. reported regarding age at first sex and condom use using the small number of MSM participating in the SSS [n=72]9. The UMHS, on the other hand, was conducted in 1996–98, which was 5–10 years earlier than the Seattle surveys. Since the mid-1990s, antiretroviral therapy for HIV was introduced, and some evidence suggests that serosorting and HIV testing frequency increased among MSM37,38. Despite these changes, we did not observe large, consistent differences in the sexual behavior patterns we evaluated in MSM between the UMHS and SEA. For example, although there were drastic changes in internet use between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, the proportion of MSM who met their partners through less formal social venues in general did not change. Another limitation of using UMHS data for this analysis was that it was conducted in different cities than the Seattle MSM surveys. Although not presented here, there were very few differences in behavior patterns between the UMHS cities suggesting that sexual behavior patterns among urban MSM were relatively similar.

A second limitation is that the low survey response rates may have affected the representativeness of our findings if there were differential participation rates associated with sexual behavior. Third, the cross-sectional data in these studies were prone to potential recall bias and the confounding of cohort effects, which can affect the estimation of longitudinal patterns. Finally, we did not directly measure the incidence of HIV or other STI. Because of this, we were unable to specifically evaluate the behaviors of persons with STI, which are clearly key with respect to transmission risk.

Our finding that MSM continued to form new partnerships later into adulthood than heterosexuals, coupled with much higher levels of concurrency and age-disassortative mixing, demonstrates important ways in which the sexual behavior and sexual network patterns of MSM and heterosexuals differ. While these differences may explain part of the observed disparity in HIV/STI rates by sexual orientation, our data provide relatively little insight into why these patterns of sexual behavior vary. Relatively few MSM partnerships in our analysis were formed in the context of personal social networks. Perhaps the separation of social and sexual networks observed among many MSM – a phenomenon that is at least partially conditioned by factors such as laws, culture, and attitudes toward homosexuality – plays a critical role in fostering the sustained HIV/STI epidemics in this population. Attitudes toward sexual minorities and laws affecting their relationships (e.g., gay marriage) are changing in many parts of the world. Thus, it is plausible that the long-standing cultural forces that promote relatively safe patterns of sexual behavior among heterosexuals have exerted relatively little influence on MSM. Insofar as social norms pertaining to same-sex relationships, marriage, and parenting continue to change, MSM sexual behavior patterns may also change, ultimately reducing risk for HIV/STI among MSM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.N.G. was supported to conduct this research by the University of Washington STD/AIDS Research Training Program (T32 AI007140) from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service. The Seattle Sex Survey RDD was funded by Public Health – Seattle & King County, the Center for Molecular and Clinical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, and the University of Washington Center for AIDS and STD. The 2003 Seattle MSM RDD was supported by a Comprehensive STD

Prevention System Syphilis Elimination grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the 2006 RDD was supported by a grant to M.R.G. (NIH K23 AI01846).

The Urban Men’s Health Study was conducted under the direction of Joe Catania and Ron Stall with support from NIMH (MH54320).

Footnotes

The authors state no conflicts of interest.

Portions of these data were presented at the 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (February 2010) in San Francisco, CA, and at the 4th Annual National Graduate Student Research Festival (November 2009) in Bethesda, MD.

Author Contribution: SNG and MRG conceptualized the present study. SNG conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft of the article. BF, SOA, LEM, and KKH designed the Seattle Sex Survey, while MG designed the Seattle MSM surveys. All authors contributed to the present study design, reviewed, and edited the article. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

List of Supplement Digital Content

References

- 1.Glick SN, Golden MR. Persistence of racial differences in attitudes toward homosexuality in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:516–523. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f275e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2009. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2009. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purcell DW, Johnson C, Lansky A, Prejean J, Stein R, Denning P, et al. Calculating disease rates for risk groups: estimating the national population size of men who have sex with men (abstract). Paper presented at: National STD Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodreau SM, Goicochea LP, Sanchez J. Sexual role and transmission of HIV Type 1 among men who have sex with men, in Peru. J Infect Dis. 2005;191 (Suppl 1):S147–58. doi: 10.1086/425268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGowan I, Taylor DJ. Heterosexual anal intercourse has the potential to cause a significant loss of power in vaginal microbicide effectiveness studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varghese B, Maher JE, Peterman TA, Branson BM, Steketee RW. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodreau SM, Golden MR. Biological and demographic causes of high HIV and sexually transmitted disease prevalence in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:458–462. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.025627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levin EM, Koopman JS, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Characteristics of men who have sex with men and women and women who have sex with women and men: results from the 2003 Seattle sex survey. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:541–546. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a819db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson SJ, Hughes JP, Foxman B, Aral SO, Holmes KK, White PJ, et al. Age- and gender-specific estimates of partnership formation and dissolution rates in the Seattle sex survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and the spread of HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:641–648. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurt CB, Matthews DD, Calabria MS, Green KA, Adimora AA, Golin CE, et al. Sex with older partners is associated with primary HIV infection among men who have sex with men in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:185–190. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c99114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Same race and older partner selection may explain higher HIV prevalence among black men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2007;21:2349–2350. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f12f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraut-Becher JR, Aral SO. Patterns of age mixing and sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:378–383. doi: 10.1258/095646206777323481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks RA, Lee SJ, Newman PA, Leibowitz AA. Sexual risk behavior has decreased among men who have sex with men in Los Angeles but remains greater than that among heterosexual men and women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20:312–324. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blair J. A probability sample of gay urban males: The use of two-phase adaptive sampling. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills TC, Stall R, Pollack L, Paul JP, Binson D, Canchola J, et al. Health-related characteristics of men who have sex with men: a comparison of those living in “gay ghettos” with those living elsewhere. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:980–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catania JA, Osmond D, Stall RD, Pollack L, Paul JP, Blower S, et al. The continuing HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:907–914. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menza TW, Kerani RP, Handsfield HH, Golden MR. Stable sexual risk behavior in a rapidly changing risk environment: findings from population-based surveys of men who have sex with men in Seattle, Washington, 2003–2006. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:319–329. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9626-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aral SO, Patel DA, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Temporal trends in sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted disease history among 18- to 39-year-old Seattle, Washington, residents: results of random digit-dial surveys. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:710–717. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175370.08709.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Disposition of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wand H, Wilson D, Yan P, Gonnermann A, McDonald A, Kaldor J, et al. Characterizing trends in HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Australia by birth cohorts: results from a modified back-projection method. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy G, Charlett A, Jordan LF, Osner N, Gill ON, Parry JV. HIV incidence appears constant in men who have sex with men despite widespread use of effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:265–272. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris M, Zavisca J, Dean L. Social and sexual networks: their role in the spread of HIV/AIDS among young gay men. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7:24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coburn BJ, Blower S. A major HIV risk factor for young men who have sex with men is sex with older partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:113–114. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d43999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris M, Kurth AE, Hamilton DT, Moody J, Wakefield S. Concurrent partnerships and HIV prevalence disparities by race: linking science and public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1023–1031. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ. Concurrent partnerships, nonmonogamous partners, and substance use among women in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:128–136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2230–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santhakumaran S, O’Brien K, Bakker R, Ealden T, Shafer LA, Daniel RM, et al. Polygyny and symmetric concurrency: comparing long-duration sexually transmitted infection prevalence using simulated sexual networks. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:553–558. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.041780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eaton JW, Hallett TB, Garnett GP. Concurrent sexual partnerships and primary HIV infection: a critical interaction. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:687–692. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9787-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodreau SM, Cassels S, Kasprzyk D, Montano DE, Greek A, Morris M. Concurrent Partnerships, Acute Infection and HIV Epidemic Dynamics Among Young Adults in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2010 Dec 30; doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9858-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:212–218. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helms DJ, Weinstock HS, Mahle KC, Bernstein KT, Furness BW, Kent CK, et al. HIV testing frequency among men who have sex with men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics: implications for HIV prevention and surveillance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:320–326. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.