Summary

Pathogens commonly disrupt host cell processes or cause damage, but the surveillance mechanisms used by animals to monitor these attacks are poorly understood. Upon infection with pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the nematode C. elegans upregulates infection response gene irg-1 using the zip-2 bZIP transcription factor. Here we show that P. aeruginosa infection inhibits mRNA translation in the intestine via the endocytosed translation inhibitor Exotoxin A, which leads to an increase in ZIP-2 protein levels. In the absence of infection we find that the zip-2/irg-1 pathway is upregulated following disruption of several core host processes, including inhibition of mRNA translation. ZIP-2 induction is conferred by a conserved upstream open reading frame in zip-2 that could de-repress ZIP-2 translation upon infection. Thus, translational inhibition, a common pathogenic strategy, can trigger activation of an immune surveillance pathway to provide host defense.

Introduction

Epithelial cells are exposed to microbes that can be pathogenic, innocuous or beneficial. In particular, epithelial cells in the human intestine are in contact with trillions of microbes, representing hundreds of different microbial species (Qin et al., 2010; Turnbaugh et al., 2007). Intestinal epithelial cells are important for defense responses, but must carefully regulate these responses so they are only activated under appropriate conditions (Lai and Gallo, 2009; Rescigno, 2011; Sansonetti, 2011; Sansonetti and Medzhitov, 2009). For example, inappropriate activation of defense responses can lead to inflammatory disorders such as inflammatory bowel diseases (Khor et al., 2011; Xavier and Podolsky, 2007). How do epithelial cells discriminate between different types of microbes? One mechanism for detecting and discriminating microbes involves recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs (Ishii et al., 2008). However, despite their name, PAMPs such as the Gram-negative cell wall component lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are found in both pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes. Thus, a more accurate term used often in plant immunity research is MAMPs (microbe-associated molecular patterns) (Ausubel, 2005; Sanabria et al., 2010). Much is known about the metazoan signaling pathways activated by PAMPs/MAMPs, involving pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs) like Toll-like receptor 4 used to detect LPS. In contrast, little is known about how animals detect pathogen attack, in order to discriminate pathogens from innocuous microbes.

Two general methods could be used to detect pathogen attack. First, virulence factors or the machinery used to deliver them could be directly detected. For example, detection of the bacterial type III secretion machinery was recently described in mammals (Auerbuch et al., 2009; Kofoed and Vance, 2011; Miao et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2011). Second, hosts could detect the effects of virulence factors, which often act to disrupt host cell processes. For example, the “danger hypothesis” posits that cells detect “damage-associated molecular patterns” or DAMPs, which can be molecules such as ATP or other cellular components that are released by damaged cells (Lotze et al., 2007; Medzhitov, 2009; Minnicozzi et al., 2011; Vance et al., 2009). Alternatively, hosts could use “surveillance pathways” to monitor either individual proteins or processes that have been altered by pathogens. Elegant work in plant immunity has established the importance of this kind of defense, which is often called effector-triggered immunity (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Jones and Dangl, 2006), and a similar phenomenon has recently been described in flies and mammals (Boyer et al., 2011). Virulence factor detection, DAMPs and surveillance pathways are all part of a conceptual framework called “patterns of pathogenesis” that could be used to discriminate pathogens from innocuous microbes (Vance et al., 2009). Many questions remain about the strategies animals use for this distinction, which is especially critical for epithelial cells that are situated on the front lines of defense.

To address the question of how animals discriminate pathogens from innocuous microbes we are investigating the C. elegans early response to infection by the bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa causes a lethal intestinal infection in the nematode C. elegans that requires some of the same virulence factors required for infections in mammalian hosts (Tan et al., 1999). We defined a set of C. elegans early infection response genes that are induced specifically by P. aeruginosa (Troemel et al., 2006). Using a reporter for one of these genes, infection response gene-1 (irg-1), we identified a bZIP transcription factor called zip-2 that is required for induction of irg-1 and for defense against killing by P. aeruginosa (Estes et al., 2010). irg-1 is induced only by pathogenic P. aeruginosa, but not by non-pathogenic P. aeruginosa strains, nor by other pathogens that kill C. elegans with similar kinetics, such as Staphylococcus aureus. Thus, irg-1 provides a specific read-out for pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa. We hypothesized that the zip-2/irg-1 response pathway was triggered either by toxin(s) produced by P. aeruginosa, or by the effects of these toxins.

Here we show that C. elegans responds to P. aeruginosa infection by detecting Exotoxin A-triggered translational inhibition. This translational inhibition leads to activation of the zip-2/irg-1 pathway, which functions in surveillance of essential host processes to provide defense. An accompanying manuscript demonstrates that Exotoxin A is sufficient to induce the zip-2/irg-1 pathway when expressed in non-pathogenic bacteria (McEwan et al., 2012). In our study we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen for regulators of irg-1 expression and found that disruption of translation, as well as disruption of other essential core processes, induces irg-1 expression in the absence of infection, and that this induction requires zip-2. We found that P. aeruginosa infection leads to translational inhibition in the intestine, and this effect is dependent on Exotoxin A. We found that host endocytosis during infection is important for irg-1 induction, suggesting that C. elegans senses P. aeruginosa virulence factors imported via endocytosis. Interestingly, we found that both infection and translational inhibition increase levels of ZIP-2 protein. Furthermore, the infection-induced increase of ZIP-2 protein expression is mediated by a region of zip-2 that contains an upstream open reading frame (uORF) that is conserved with the sister species C. briggsae. Translation attenuation in this uORF by Exotoxin A could thus act to switch on ZIP-2 expression and its downstream effectors upon infection. This toxin-induced method of defense may represent a form of surveillance immunity, comprising an important part of the innate immune armamentarium that enables animals to discriminate pathogens from innocuous microbes.

Results

Disruption of core host processes activates zip-2-dependent irg-1 expression in the absence of infection

To identify regulators of the zip-2/irg-1 response pathway we conducted a genome-wide RNAi screen by feeding irg-1p::GFP animals RNAi clones of E. coli (the laboratory food source for C. elegans). This collection of RNAi clones corresponded to approximately 94% of C. elegans genes. We then screened for constitutive irg-1p::GFP expression on E. coli in the absence of infection. Out of ~18,000 RNAi clones tested, we identified 57 RNAi clones that caused increased expression of irg-1p::GFP in comparison to control RNAi-treated worms (Table S1). Genes identified in this screen fell into several functional classes, including tRNA synthetases, translation factors, histones, metabolic enzymes, and regulators of fatty acid homeostasis. As noted in Table S1, RNAi against most of these genes caused some sort of developmental delay, indicating that disruption of several essential processes can cause upregulation of irg-1 expression.

To characterize these RNAi hits, we investigated whether their effects on irg-1 expression were dependent on the bZIP transcription factor zip-2, similar to the effects of P. aeruginosa infection. Our previous studies utilized the zip-2(tm4067) mutation, which is likely a partial loss-of-function mutation since it causes less severe defects than zip-2 RNAi (Estes et al., 2010). For this study, we characterized an additional deletion allele of zip-2 called tm4248 (Figure S1). We found that the zip-2(tm4248) mutation causes greater defects in irg-1 and irg-2 induction than the zip-2(tm4067) mutation (Figure 1A–D). In addition, zip-2(tm4248) had slight defects in induction of other genes that are not affected by zip-2(tm4067) or zip-2 RNAi (Figure 1D, (Estes et al., 2010). In summary, zip-2(tm4248) appears to be a stronger loss-of-function allele than zip-2(tm4067), and has a pronounced defect in irg-1 induction.

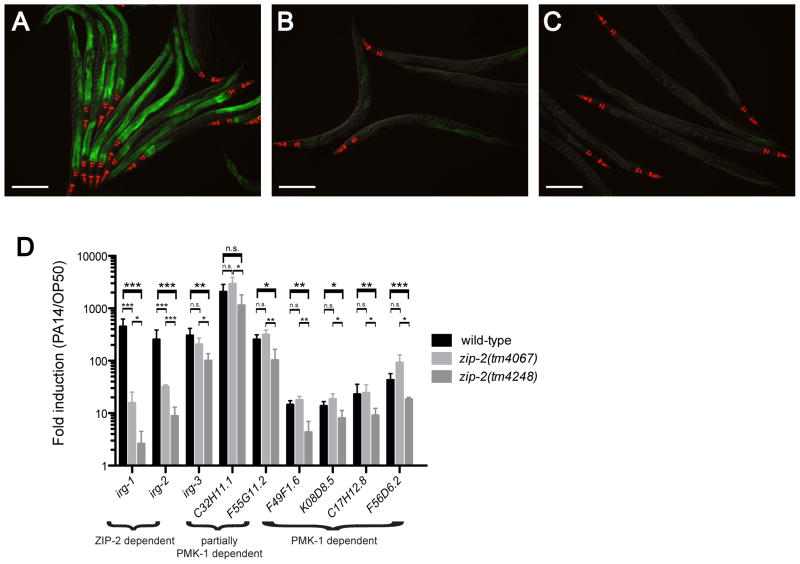

Figure 1. zip-2(tm4248) mutants are defective in inducing irg-1 and irg-2 in response to infection.

(A) Wild-type irg-1p::GFP animals infected with PA14. (B) zip-2(tm4067);irg-1p::GFP animals infected with PA14 – note reduced GFP fluorescence. (C) zip-2(tm4248);irg-1p::GFP animals infected with PA14 – note even further reduced fluorescence. Green is irg-1p::GFP and red is myo-2::mCherry expression in the pharynx as a marker for the transgene. Images in (A–C) are overlays of green, red and Nomarski channels. Scale bar is 200 μm. (D) qRT-PCR comparison of PA14 –induced gene expression in wild-type, zip-2(tm4067) and zip-2(tm4248) mutants. Note greater defect in irg-1 induction in zip-2(tm4248) compared to zip-2(tm4067). Results shown are the average of three independent biological replicates, error bars are SD. *** is p<0.001, ** is p<0.01, * is p<0.05 using one-sample one-tail or two-sample two-tail t-tests. n.s is not significant. See also Figure S1.

By performing RNAi knockdown in the zip-2(tm4248) deletion background, we found that many of the hits from our RNAi screen no longer had an effect on irg-1 expression, indicating their dependence on wild-type zip-2 (Table S1). For example, RNAi against all 19 tRNA synthetases, and against translation elongation and termination factor genes, caused irg-1p::GFP induction that was dependent on zip-2. However, RNAi against translation initiation factor genes caused irg-1p::GFP induction that was largely independent of zip-2. Histones fell into both zip-2-dependent and zip-2-independent classes: H2A and H2B histones had zip-2-dependent effects, whereas H3 and H4 histones had zip-2-independent effects. Thus, most RNAi clones from our screen that induce irg-1 in the absence of infection appear to signal through zip-2, although other pathways may also be involved (see Text S1 for details on other hits).

Translational inhibition activates irg-1 mRNA expression and requires zip-2

RNAi against tRNA synthetase genes caused a very strong induction of irg-1 (measured by irg-1p::GFP fluorescence and qRT-PCR of endogenous irg-1 mRNA) that in all cases was dependent on zip-2 (Table S1 and Figure 2A–D). In addition, we found other genes in our screen that are important for translational elongation, such as translation elongation factor 2 (EF-2), eef-2: RNAi against eef-2 caused irg-1 induction that was dependent on zip-2 (Table S1). Therefore, we next asked whether direct inhibition of translation elongation with a chemical inhibitor would have the same effect. We treated irg-1p::GFP animals with cycloheximide, a translational elongation inhibitor (Schneider-Poetsch et al., 2010), and found that it strongly induced irg-1 (Figure 2E), which was dependent on zip-2. Thus, either genetic or chemical inhibition of mRNA translation led to zip-2-dependent upregulation of irg-1 expression.

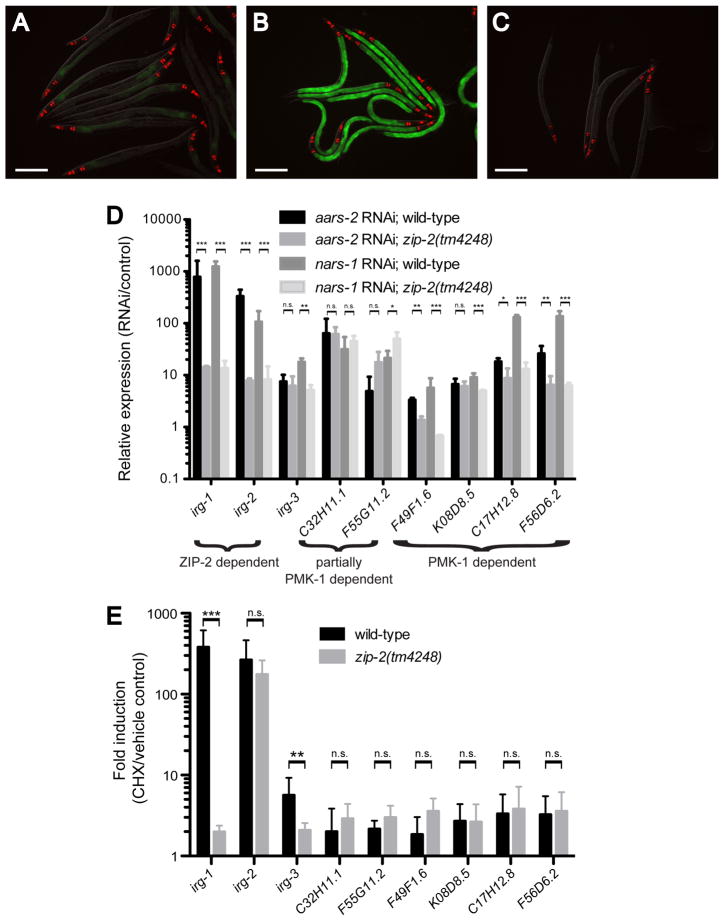

Figure 2. Translational inhibition induces zip-2-dependent expression of irg-1 in the absence of infection.

(A) RNAi control (L4440)-treated irg-1p::GFP animals grown on E. coli. (B) tRNA synthetase nars-1 RNAi treated irg-1p::GFP animals grown on E. coli have increased GFP expression. (C) nars-1 RNAi treated irg-1p::GFP;zip-2(tm4248) animals grown on E. coli do not have increased GFP expression. Green is irg-1p::GFP and red is myo-2::mCherry expression in the pharynx as a marker for presence of the transgene. Images in (A–C) are overlays of green, red and Nomarski channels. Scale bar is 200 μm. (D) qRT-PCR comparison of infection response gene expression in animals grown on E. coli, as upregulated by aars-2 or nars-1 tRNA synthetase RNAi treatment compared to L4440 control treated animals, in wild-type or zip-2(tm4248) mutant background. (E) qRT-PCR comparison of infection response gene expression induced by 4 hours of 2 mg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) treatment compared to ethanol (vehicle control), in wild-type or zip-2(tm4248) mutant background. (D, E) Results shown are the average of three independent biological replicates, error bars are SD. *** is p<0.001, ** is p<0.01, * is p<0.05 using one-sample one-tailed t-test. n.s is not significant. See also Table S1.

We also examined whether translational inhibition caused induction of other P. aeruginosa infection-induced genes. Infection response gene-2 (irg-2) is another gene induced by P. aeruginosa via zip-2 (Estes et al., 2010). qRT-PCR analysis indicated that translational inhibition either through tRNA synthetase RNAi or cycloheximide treatment caused robust induction of irg-2 (Figure 2D–E). However, while tRNA synthetase RNAi induction of irg-2 was dependent on zip-2, cycloheximide induction of irg-2 was independent of zip-2, suggesting that cycloheximide may also activate other pathways. Cycloheximide treatment caused very little induction of zip-2-independent genes like C32H11.1 (Figure 2E), which we previously demonstrated to depend either partially or completely on the PMK-1 p38 MAPK pathway (and not on zip-2) for their induction by P. aeruginosa (Estes et al., 2010; Troemel et al., 2006). In contrast, tRNA synthetase RNAi did cause robust induction of C32H11.1 and other p38 MAPK-dependent genes (Figure 2D). In summary, either genetic or chemical inhibition of translation caused induction of the zip-2/irg-1 pathway in the absence of infection, although translational inhibition may also activate other signaling pathways.

P. aeruginosa infection blocks protein production in the intestine

The results described above suggest that P. aeruginosa infection might induce irg-1 mRNA expression through inhibition of host translation. To examine this possibility, we took an image-based approach to analyzing translational efficiency during infection with P. aeruginosa. We used transgenic animals that express a heat shock inducible GFP reporter to test whether mRNA transcripts newly made during P. aeruginosa infection are translated into protein. dvIs70[hsp-16.2::GFP] transgenic animals induce GFP broadly throughout the animal in many tissues after heat shock treatment (Link et al., 1999), (Figure 3A, C, E). In striking contrast, when animals were first infected with P. aeruginosa and then heat shocked, they have much less GFP induction in the intestine, which is the site of P. aeruginosa attack (Figure 3B, D, E). However, they retain relatively normal GFP induction in other tissues, such as the pharynx, hypodermis and eggs. One possible explanation for this result is that P. aeruginosa blocks heat shock-induced GFP transcription during infection. However, qRT-PCR analysis indicated that GFP mRNA was not expressed less in P. aeruginosa-infected animals compared to control E. coli-fed animals (Figure S2A). We also performed RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to examine GFP mRNA levels specifically in the intestines of infected and uninfected animals. Importantly, there was not less GFP mRNA signal in the intestines of P. aeruginosa infected animals compared to uninfected animals, and in fact there was more signal (Figure S2B). Therefore, GFP transcription does not appear to be blocked in the intestine of infected animals. Altogether these results suggest that P. aeruginosa infection impairs mRNA translation in the C. elegans intestine early during the infection process.

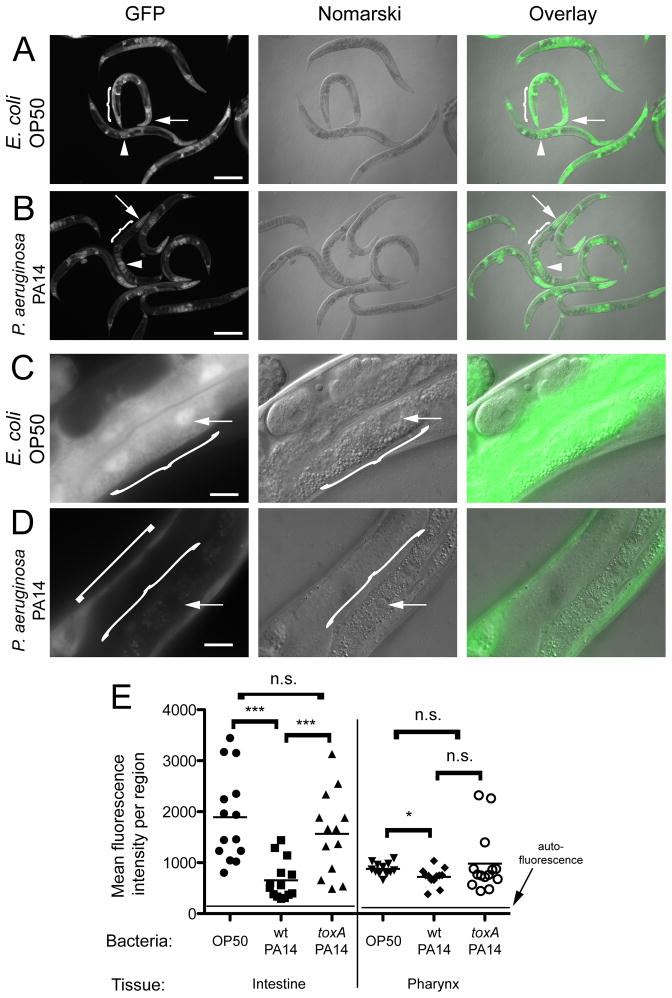

Figure 3. P. aeruginosa infection blocks production of heat shock induced GFP in the intestine.

(A) Animals grown on E. coli: hsp-16.2::GFP is induced broadly. (B) Animals infected with P. aeruginosa: hsp-16.2::GFP is still induced in many tissues, but is induced less in the intestine. In (A and B) pharynx indicated with arrow, developing embryos indicated with arrowhead, and intestine indicated with curly brace. Scale bar is 200 μm. (C) Animal grown on E. coli: hsp-16.2::GFP is induced strongly in the intestine, indicated with curly brace. (D) Animal infected with P. aeruginosa: hsp-16.2::GFP is not induced in the intestine indicated with curly brace, but is induced in hypodermis, indicated with square bracket. (C and D) Arrow indicates an intestinal nucleus and scale bar is 20 μm. (E) GFP fluorescence levels after heat shock in either the intestine or pharynx of animals fed either E. coli OP50, infected with wild-type P. aeruginosa PA14, or infected with toxA mutant P. aeruginosa. Each dot represents fluorescence quantified in one animal, horizontal lines for each sample indicate the mean, and the horizontal line at the bottom indicates the level of autofluorescence. Difference in the intestine is significant between OP50 and wild-type PA14, and between wild-type and toxA mutant PA14 (*** p<0.001 with a two-tailed t-test), but not between OP50 and toxA mutant PA14 (p=0.32). Difference in the pharynx is moderately significant between OP50 and wild-type PA14 (* p<0.05 with a two-tailed t-test) and not significant between wild-type PA14 and toxA mutant (p=0.16), or OP50 and toxA mutant PA14 (p=0.56). Similar results were obtained in seven independent experiments comparing OP50 and wild-type PA14, and four independent experiments also comparing toxA mutant PA14. See also Figure S2.

How might P. aeruginosa infection cause translational inhibition in the C. elegans intestine? P. aeruginosa expresses a toxin called Exotoxin A (ToxA), which is endocytosed by host cells and then ADP ribosylates EF-2 to inhibit host translation (FitzGerald et al., 1980; Ogata et al., 1990). In order to determine whether ToxA is required for the P. aeruginosa-mediated block of intestinal translation, we tested whether a toxA mutant (Rahme et al., 1995; Tan et al., 1999) blocks heat shock induction of GFP. Interestingly, we found that the toxA mutant did not block heat shock-induced GFP expression (Figure 3E). Therefore, ToxA is required for the block in intestinal GFP production caused by P. aeruginosa infection.

Because ToxA is required for infection-induced translational inhibition (Figure 3E), and translational inhibition causes irg-1 induction (Figure 2), we next asked whether ToxA was required for irg-1 induction upon infection. We found that the toxA P. aeruginosa mutant still induced irg-1::GFP, suggesting that ToxA is not required for this response (data not shown). Then we used qRT-PCR to quantitatively test the toxA mutant for its ability to induce endogenous irg-1 mRNA expression and found that the toxA mutant had a slight but reproducible defect in irg-1 mRNA induction compared to wild-type P. aeruginosa (Figure S3A). The fact that toxA mutants are strongly defective in translational inhibition, but only slightly defective for irg-1 induction, suggests that P. aeruginosa may produce additional toxins to block other pathways that also regulate irg-1 induction. Such pathways could include those identified in our screen (Table S1).

Endocytosis is important for induction of infection response genes

We next investigated whether endocytosis is required to trigger an infection response in the C. elegans intestine during infection. Previous work with electron microscopy indicated that P. aeruginosa bacterial cells do not enter C. elegans intestinal cells in the first 24 hours of infection (Irazoqui et al., 2010). However, it is well-established that Exotoxin A and other bacterial toxins can enter host cells via endocytosis (FitzGerald et al., 1980; Ogata et al., 1990; Zdanovsky et al., 1993). To disrupt endocytosis we used a temperature-sensitive dyn-1(ky51ts) mutant, which is defective in dynamin, a protein required for fission of clathrin-dependent endocytic vesicles in the intestine (Clark et al., 1997; Grant et al., 2001). We grew dyn-1(ky51ts);irg-1p::GFP animals at the permissive temperature to allow them to develop normally. Then we shifted them to the restrictive temperature during the L4/young adult stage, infected them with P. aeruginosa, and examined irg-1::GFP induction. We found that pathogen-induced irg-1p::GFP expression was much lower in dyn-1 mutant animals compared to wild-type controls (Figure 4A–B), suggesting that endocytosis is indeed required to trigger full irg-1 induction. We next examined irg-1 mRNA induction in dyn-1 mutants with qRT-PCR and found that induction of many infection response genes was abrogated. This result indicates that endocytosis is required for triggering irg-1 induction, as well as triggering induction of other genes in response to infection, including ZIP-2-dependent transcripts like irg-2, and ZIP-2-independent transcripts like C32H11.1 (Figure 4C). Because dyn-1 mutants have a slower feeding rate, we examined pathogen load but found that it was similar in wild-type animals and dyn-1 mutants (Figure 4D). Thus a feeding defect does not likely account for the lower gene induction in dyn-1 mutants. Our results suggest that dyn-1 mutants fail to induce irg-1 and other infection response gene expression due to a defect in intestinal endocytosis.

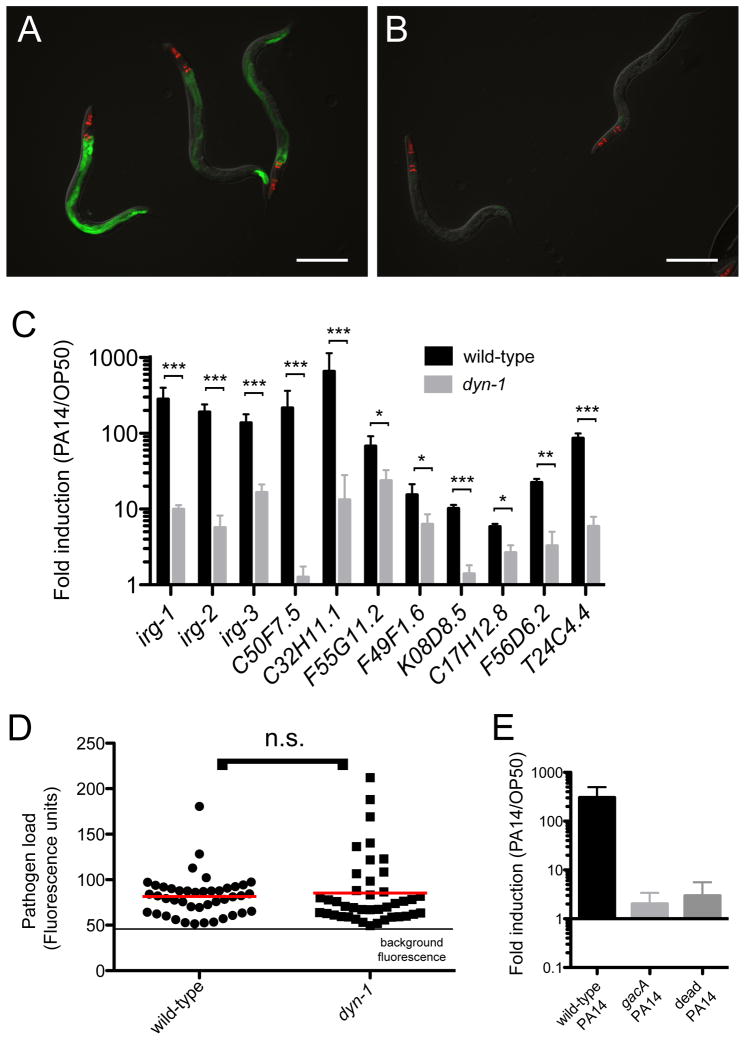

Figure 4. Endocytosis is important for induction of irg-1 and other infection response genes.

(A)Wild-type irg-1p::GFP animals infected with P. aeruginosa for 8 hours. (B) dyn-1(ky51ts);irg-1p::GFP mutant animals infected with P. aeruginosa for 8 hours. (A, B) Green is irg-1p::GFP, red is myo-2::mCherry expression in the pharynx as a marker for presence of the transgene. (C) qPCR of wild-type vs. dyn-1(ky51ts) endocytosis-defective mutants. Results shown are the average of three independent biological replicates. Error bars are SD. *** is p<0.001, ** is p<0.01, * is p<0.05 using one-sample two-tailed t-test. (D) Pathogen load in wild-type and dyn-1(ky51ts) mutants. Each dot represents the entire intestine quantified in one animal, the red horizontal line indicates the mean of several animals and the horizontal line at bottom indicates autofluorescence. Difference is not significant (p=0.26, with a two-tailed t-test). (E) qRT-PCR measurements of irg-1 mRNA show that it is highly induced by wild-type PA14, but not by gacA mutant PA14 or heat-killed PA14. Results are the average of three independent experiments, error bars are SD. See also Figure S3.

Our previous microarray studies indicated that all of the genes analyzed in Figure 4C have less induction in response to the less virulent gacA mutant than to wild-type P. aeruginosa, suggesting that they are induced by virulence factors (Troemel et al., 2006). Further analysis using heat-killed PA14 (which is completely non-pathogenic) indicated that there was almost no induction of these genes as assessed by qRT-PCR (Irazoqui et al., 2010), although irg-1 was not analyzed in this study. In a separate study we analyzed the irg-1 response to P. aeruginosa virulence using gacA mutants and 19 P. aeruginosa strains and found a close correlation between irg-1 induction and virulence (Estes et al., 2010). To extend this analysis, we also analyzed irg-1 induction by heat-killed PA14 and found very little induction, similar to the response to gacA (Figure 4E). Because dyn-1 is defective in induction of these genes, which are largely or entirely a response to virulence, this suggests that endocytosis of virulence factors is important for the C. elegans transcriptional response to infection.

P. aeruginosa infection and translational inhibition activate ZIP-2::GFP production

To learn more about the mechanism of irg-1 activation, we examined regulation of zip-2 expression, since zip-2 controls irg-1 induction. zip-2 mRNA appears to be highly expressed in uninfected conditions based on EST analysis, in situ hybridization and microarray analysis (see Text S1 for more details). And our previous microarray analysis indicated that zip-2 mRNA expression only increases 2.7-fold upon infection (Estes et al., 2010). To further examine zip-2 mRNA expression and tissue distribution, we generated a transgene that contains 2 kb of genomic DNA upstream of the predicted zip-2 translational start site fused to GFP (zip-2p::GFP, aka F21). Animals containing this transgene showed GFP expression in the pharynx, as well as expression throughout the intestine (Figure S4A). We found that intestinal expression was greatly reduced when these animals were fed zip-2 RNAi (Figure S4B), perhaps because the zip-2 RNAi clone targets the zip-2 5′UTR, or because ZIP-2 regulates its own expression. However, consistent with microarray analysis, this expression did not change substantially upon infection with P. aeruginosa (Figure S4C and see below). Altogether these data indicate that zip-2 mRNA levels are relatively high in uninfected animals and do not increase substantially upon infection.

Next, we investigated whether induction of ZIP-2 protein could account for the robust irg-1 induction upon infection. To examine ZIP-2 expression and localization, we generated transgenic animals that express ZIP-2 C-terminally tagged with GFP. Specifically, they contain 2 kb upstream of the zip-2 predicted ATG start site followed by the zip-2 genomic coding region with GFP fused to the C-terminus right before the predicted ZIP-2 stop codon. These ZIP-2::GFP transgenic animals showed virtually no expression when feeding on E. coli, suggesting that while zip-2 mRNA is expressed in uninfected animals, it is not efficiently translated into protein (Figure 5A). Strikingly, we found that ZIP-2::GFP was induced in animals infected with P. aeruginosa, with nuclear localization in intestinal cells (Figure 5C). At 4 hours after infection (the time of robust irg-1 induction), we found that animals infected with P. aeruginosa had significantly more GFP expression than animals feeding on E. coli (Figure 5E). In order to assess whether ZIP-2::GFP localization reflects the endogenous localization of ZIP-2, we confirmed that it rescued the defect of irg-1 mRNA induction in zip-2(tm4248) mutants (Figure 5F). Therefore, the ZIP-2::GFP transgene is functional, and its increase in levels upon infection and nuclear localization likely reflect the endogenous expression and localization of ZIP-2 protein.

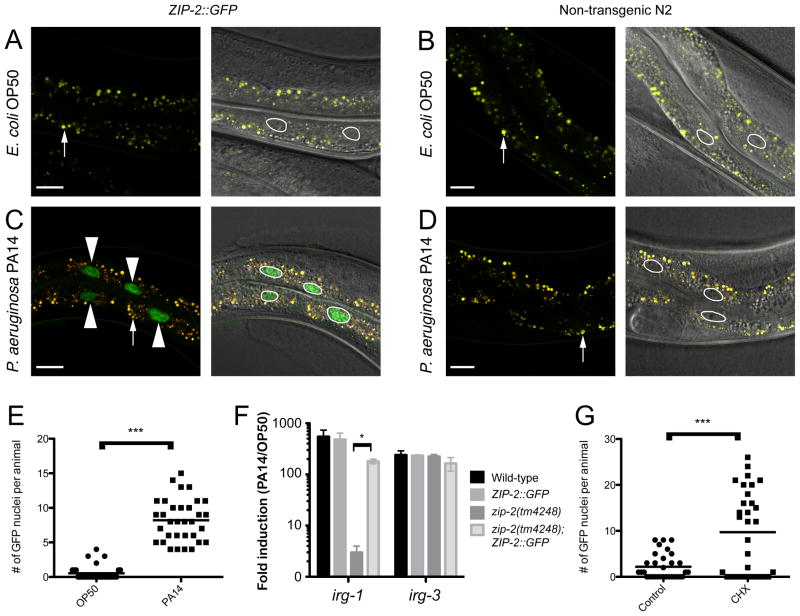

Figure 5. ZIP-2::GFP transgene is induced by PA14 infection and translational inhibition.

(A–D) In each panel, the left image shows GFP fluorescence in green indicated with arrowheads, and autofluorescence in yellow indicated with small arrows; the right image shows an overlay of Nomarski with the left image and white outlines to indicate nuclei. Scale bars are 20 μm. (A) ZIP-2::GFP transgenic animals do not show GFP expression when feeding on E. coli OP50, only autofluorescence. (B) N2 (non-transgenic) animals show autofluorescence on E. coli. (C) ZIP-2::GFP transgenic animals show nuclear GFP expression in the intestine when infected with P. aeruginosa PA14. Arrowheads indicate four examples of nuclei expressing GFP. (D) N2 animals show autofluorescence on PA14. (E) Number of intestinal nuclei with GFP expression per animal 4 hours after transfer to PA14 or OP50; each dot represents an animal and the horizontal bar indicates the mean. (F) qRT-PCR shows that the ZIP-2::GFP transgene rescues the irg-1 induction defect of zip-2(tm4248) mutants. Results are the average of two biological replicates, error bars are SD, * p<0.05 with two-tailed t-test. (G) Number of intestinal nuclei with GFP expression in animals 6 hours after transfer to 2 mg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) or ethanol (vehicle control); each dot represents an animal and the horizontal bar indicates the mean. (E and G) Experiments shown are representative of at least three independent biological replicates, >30 animals scored per condition in each experiment. *** indicates p<10−3 with a two-tailed t-test. See also Figure S4.

Our data suggest that a key event in P. aeruginosa infection leading to zip-2-dependent irg-1 induction is translational inhibition. To determine whether translational inhibition with cycloheximide could activate ZIP-2::GFP production, we compared ZIP-2::GFP expression in animals treated with cycloheximide to those treated with vehicle control. Similar to P. aeruginosa infection, we found that cycloheximide treatment caused activation of ZIP-2::GFP expression in the intestine (Figure 5G). Thus, our data suggest that P. aeruginosa infection in C. elegans causes translational inhibition, which leads to increased levels of ZIP-2 protein.

The zip-2 upstream region contains upstream open reading frames, and confers infection-induced upregulation

The increase in ZIP-2 protein levels we observed with infection and translational inhibition is reminiscent of the translational activation of yeast GCN4 and mammalian ATF4, which are bZIP transcription factors regulated by nutrient stress (Hinnebusch, 2005; Vattem and Wek, 2004). Translation of these transcription factors is regulated by upstream ORFs (uORFs) in their 5′UTR’s. Therefore we investigated whether the zip-2 5′UTR contains uORFs. There are two mRNA isoforms predicted for zip-2 based on EST analysis, both of which have long 5′UTRs (Figure 6A). Both of these isoforms contain an intron spliced out of the 5′UTR. We used an open reading frame finder to look for additional ORFs in this region and identified three predicted uORFs in the zip-2 5′UTR (Figure 6A). uORFa starts before the predicted zip-2 start, and overlaps the zip-2 ORF out-of-frame. uORFb and uORFc start further upstream, and stop before the predicted zip-2 start. uORFb and uORFc both cross the 5′UTR splice site, providing a possible explanation for why the “untranslated region” has an intron – it may indeed be translated.

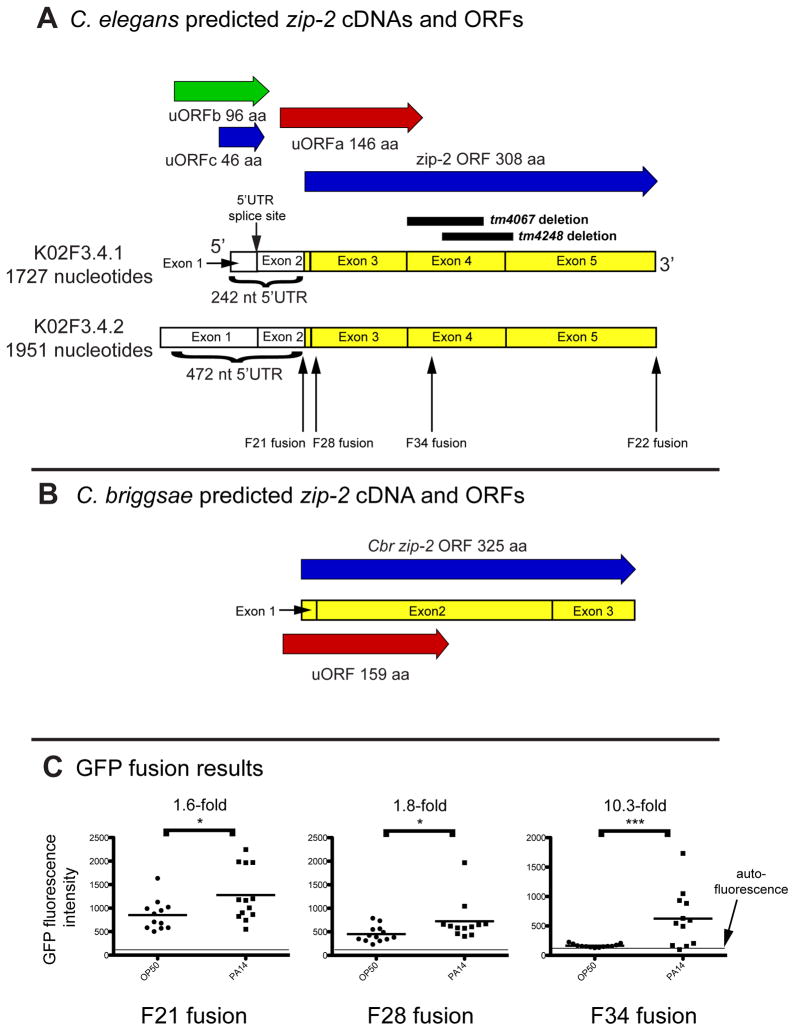

Figure 6. The zip-2 upstream region contains uORFs and confers upregulation upon infection.

(A) K02F3.4.1 is a major mRNA isoform for zip-2, K02F3.4.2 is a minor mRNA isoform for zip-2. Both contain the predicted zip-2 ORF of 308 amino acids. zip-2(tm4067) and zip-2(tm4248) alleles are deletions (see Figure S1). Three predicted uORFs: uORFa in the -1 frame, uORFb in the -2 frame, uORFc in frame with ZIP-2. F21, F22, F28 and F34 refer to the location of GFP fusions. (B) C. briggsae predicted zip-2 cDNA and ORFs. uORF is in the -1 frame. Note that this predicted uORF has similar start, stop and frame as uORFa in C. elegans zip-2. (C) zip-2 region with uORFa confers induction of GFP upon infection with P. aeruginosa. Strains analyzed in this panel include jyEx6 (F21), jyEx21 (F28) and jyEx67 (F34). Results are from the same experiment with all strains tested in parallel. Each dot represents fluorescence quantified in one animal, the mean is shown with a horizontal line in the middle, and autofluorescence is indicated by a line at the bottom. * p<0.05, *** p<0.005 with a two-tailed t-test. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

If uORFs are important for ZIP-2 function, we reasoned that they would be conserved in the sister species Caenorhabditis briggsae. We analyzed the sequence upstream of the C. briggsae ZIP-2 ortholog, a predicted 325 amino acid protein that is 46% identical in the amino acid level to C. elegans ZIP-2. Because of a lack of EST data we only analyzed the region just upstream of the predicted C. briggsae ZIP-2 start and found a uORF strikingly similar to C. elegans uORFa in length, frame and placement (Figure 6B; see Text S1 for uORF amino acid sequences). In summary, an overlapping uORF appears to be a conserved feature of ZIP-2, supporting a possible role in ZIP-2 regulation.

To examine whether the uORFs could confer infection-induced regulation of zip-2 expression, we generated transgenic lines containing the zip-2 upstream region and portions of the overlapping uORFa fused to GFP, in frame with the zip-2 ORF (locations of GFP fusions are illustrated in Figure 6A). We then infected animals containing these transgenes and compared GFP expression in uninfected animals to P. aeruginosa-infected animals. The zip-2p::GFP fusion called F21 contains none of the ZIP-2 coding region and part of uORFa. This transgene showed a small but significant upregulation upon infection (1.6-fold, * p<0.05), as did zip-2p::GFP fusion F28 (1.8-fold, * p<0.05), which contains 8 more amino acids of uORFa (Figure 6C). By comparison, zip-2p::GFP fusion F34, which contains the entire uORF, showed robust upregulation upon infection (10.3-fold, *** p<0.005, Figure 6C), consistent with the model that uORFa plays an important role in the infection-induced upregulation of ZIP-2 protein levels. In addition, there was less transgene expression in uninfected F34 transgenic animals, compared to F21 or F28 transgenic animals, suggesting that uORFa may act to repress ZIP-2 mRNA translation in the absence of infection. In summary the zip-2 upstream region contains a conserved uORF, which confers induction of ZIP-2 expression upon P. aeruginosa infection.

Discussion

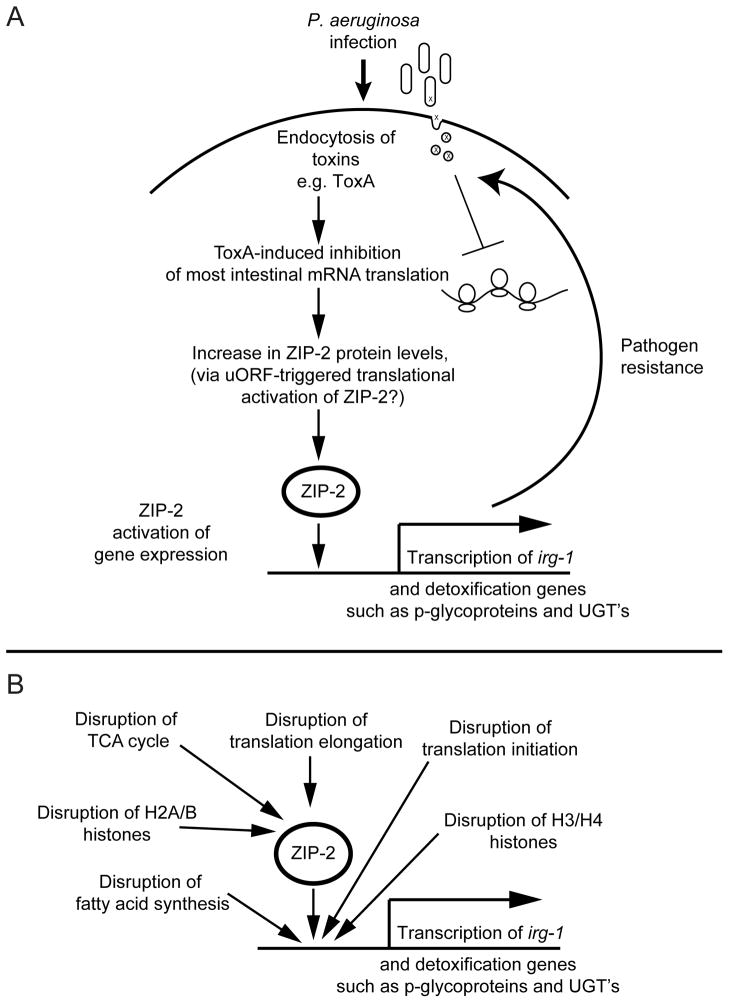

Epithelial cells regularly encounter a variety of microbes, only some of which are pathogenic. Thus, these cells need specific mechanisms to determine when microbes have launched a pathogenic attack and need to respond appropriately. We describe a surveillance pathway in C. elegans intestinal epithelial cells that detects translational inhibition as a method to discriminate pathogens from innocuous microbes (Figure 7A). Our data indicate that upon P. aeruginosa infection, C. elegans intestinal cells likely endocytose Exotoxin A, which ADP ribosylates EF-2 to inhibit mRNA translation. Inhibition of translation then switches on ZIP-2 translation (see below) to induce expression of irg-1 and other downstream effectors to provide defense. We previously showed that zip-2 contributes to defense against killing by P. aeruginosa (Estes et al., 2010), and an accompanying manuscript demonstrates that zip-2 is required for defense against killing by E. coli expressing ToxA (McEwan et al., 2012). ZIP-2 may provide defense by regulating expression of genes such as p-glycoprotein transporters that could pump toxins out of the cell, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases that could inactivate toxins (Estes et al., 2010).

Figure 7. Model for induction of C. elegans zip-2/irg-1 surveillance pathway.

(A) Endocytosis of P. aeruginosa toxins causes translational inhibition, which activates zip-2 immune response pathway. (B) zip-2/irg-1 pathway is activated by disruption of several core host processes. See Discussion for details.

We only found a minor role for Exotoxin A in irg-1 induction caused by P. aeruginosa infection (Figure S3). However, the accompanying manuscript demonstrates that ToxA expression in non-pathogenic bacteria is sufficient to cause robust irg-1 induction, and this induction is dependent on the catalytic residues in ToxA (McEwan et al., 2012). Therefore, ToxA may act redundantly with other toxins that inhibit other essential host processes that control irg-1 expression, such as those we identified in our RNAi screen (Figure 7B). This redundancy would not be surprising, as studies of pathogens like L. pneumophila have uncovered extensive virulence factor redundancy (O’Connor et al., 2011).

How does infection-induced translational inhibition ultimately result in increased levels of ZIP-2 protein? The zip-2 5′UTR contains several uORFs including a conserved overlapping uORF, and this region confers infection-induced upregulation of ZIP-2 translation. Interestingly, there are several examples from yeast to mammals of stress response factors only being translated into protein during times of stress, and this regulation is conferred by uORFs (Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009). For example, the yeast bZIP transcription factor GCN4 is only translated during amino acid starvation and translational inhibition (Hinnebusch, 2005). When amino acids and/or ternary complex is limiting, the scanning ribosomes fail to initiate translation at the inhibitory uORFs, and thus can initiate translation at the start codon of GCN4. This phenomenon is conserved with the mammalian bZIP transcription factor ATF4, which also responds to amino acid starvation (Vattem and Wek, 2004). A related but distinct example comes from the mammalian cat-1 amino acid transporter, which contains a uORF that causes formation of an internal ribosomal entry site when translation elongation is attenuated, in order to induce translation of cat-1 during starvation (Fernandez et al., 2005; Yaman et al., 2003). Perhaps the zip-2 5′UTR and uORFs use a related mechanism to specifically induce ZIP-2 translation during infection. An alternative non-uORF-based explanation for our results is that zip-2 mRNA is normally bound by a labile repressor, which is lost upon translational attenuation to then allow translation of zip-2 mRNA. This model shares similarity with NFκB activation in macrophages by translation attenuation, which causes decreased levels of the labile repressor IκB, ultimately leading to NFκB nuclear translocation and cytokine gene expression (Fontana et al., 2011). And perhaps uORFa itself encodes a repressor protein, although BLAST analysis of uORFa protein sequence (Text S1) against the nr database yielded no hits with an E-value less than 0.4. Further work will be needed to distinguish among these models for how infection-induced inhibition of translation can somewhat paradoxically lead to an increase in ZIP-2 protein.

Our data indicate that the zip-2/irg-1 pathway provides surveillance for several core host functions, in addition to mRNA translation (Figure 7B). For example, we found that RNAi against histones induced irg-1 expression. However, there was a distinction between central histone components H3/H4, which are the histones loaded onto DNA first, and H2A/B histones, which are loaded next and are more easily removed (Burgess and Zhang, 2010). RNAi against H3/H4 histones caused zip-2-independent irg-1 induction, while RNAi against H2A/B histones caused zip-2-dependent irg-1 induction. A similar theme emerged from RNAi against translation factors. RNAi against initiation factors caused mostly zip-2-independent irg-1 induction, while RNAi against elongation factors like EF-2 (eef-2) caused zip-2-dependent irg-1 induction. One explanation for these results is that an unidentified transcription factor, possibly in parallel to zip-2, mediates irg-1 activation upon disruption of early steps in core host functions, while ZIP-2 alone mediates irg-1 activation upon disruption of later steps, like H2A/B loading and translation elongation. RNAi against translation factors also activates gene expression mediated by SKN-1, another C. elegans bZIP transcription factor (Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010). Interestingly, there are distinct mechanisms of SKN-1-dependent gene activation depending on whether initiation or elongation are inhibited. Further work will be needed to identify the transcription factors involved in surveillance of early steps in host functions and how these factors are integrated with ZIP-2 and SKN-1.

In addition to translation and histones, we also found that RNAi clones that perturb mitochondrial function and fatty acid synthesis cause upregulation of irg-1 expression. A recent study has shown that disruption of some of the same core processes identified here, including translation and mitochondrial pathways, can cause aversion behavior and defense gene expression in C. elegans (Melo and Ruvkun, 2012). Thus, both escape responses and upregulation of immune gene expression appear to be activated by surveillance pathways that monitor many essential host functions.

We found an important role for endocytosis in the C. elegans intestinal immune response. Interestingly, endocytosis is also important for the C. elegans hypodermal response to infection, where host defense proteins localize to endosomes (Dierking et al., 2011). We propose that endocytosis serves to internalize P. aeruginosa-derived proteins like Exotoxin A, since P. aeruginosa bacterial cells themselves are not found inside intestinal cells within 24 hours (Irazoqui et al., 2010). Exotoxin A has been long known to be endocytosed by mammalian cells (FitzGerald et al., 1980). Perhaps much of the C. elegans epithelial response to infection is triggered by endocytosis of toxins, instead of by MAMPs/PAMPs binding to cell surface PRRs, as occurs in professional immune cells of flies and mammals (although endocytosis has recently been shown to be important for Toll signaling in flies (Huang et al., 2010)). In contrast to flies and mammals, C. elegans lacks professional immune cells, and PRRs have not yet been found. While there is a single C. elegans Toll-like receptor, it is not important for most immune responses (Pujol et al., 2001; Pukkila-Worley and Ausubel, 2012). Our previous results indicated that the majority of the C. elegans transcriptional response to P. aeruginosa is activated by virulence factors, not by PAMPs/MAMPs (Estes et al., 2010; Troemel et al., 2006) (Irazoqui et al., 2010), (Figure 4E). While there is evidence that C. elegans responds to PAMPs/MAMPs (Irazoqui et al., 2010; Pukkila-Worley et al., 2011), we speculate that detection of toxins by endocytosis is a major resistance strategy for C. elegans, whose defense relies heavily on epithelial cells. Perhaps toxin-sensing is an optimal mode of defense for epithelial cells, which are regularly in contact with both pathogenic and innocuous microbes.

Translational inhibition is a very common pathogenic attack strategy. In addition to infection by bacteria, infection by viruses commonly causes arrest of host translation to allow viral transcripts privileged access to host translational machinery (Walsh and Mohr, 2011). Because of the ubiquitous nature of this form of attack, it would not be surprising if response to translational inhibition would be a conserved form of host defense. For example, translation inhibition induces cytokine production in mammals (Youngner et al., 1965). As mentioned above, there is a role for NFκB in this response, which can be activated by a cocktail of translation inhibitors delivered by the bacterial pathogen L. pneumophila (Fontana et al., 2011). There are several other bacterial toxins known to target host translation, such as Diphtheria toxin, Ricin toxin and Shiga toxin. Indeed, the translational elongation inhibitor cycloheximide was originally isolated from the soil bacterium Streptomyces griseus (Schneider-Poetsch et al., 2010). These translation-blocking toxins cause substantial impact on human health, for example by causing lethal gastrointestinal infections (Bielaszewska et al., 2011; Frank et al., 2011). Like Exotoxin A, these toxins can be endocytosed into the host cell to block translation (Deng and Barbieri, 2008). Perhaps human intestinal epithelial cells (and also professional immune cells) monitor disruption of host protein synthesis using a surveillance pathway similar to what we describe in C. elegans intestinal epithelial cells, in order to specifically detect and respond to pathogen attack.

Experimental Procedures

RNAi experiments and feeding RNAi screen

Feeding RNAi experiments were performed as described (Estes et al., 2010). The Ahringer and Vidal Uniques RNAi libraries were used for the irg-1p::GFP RNAi screen (Kim et al., 2005). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Pathogen infection experiments

P. aeruginosa infection experiments were performed as described (Powell and Ausubel, 2008). In brief, overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 were seeded onto SK plates, then incubated at 37°C for 24 h, followed by 25°C for 24 h. Animals were washed onto plates and were harvested 4 h later for qRT-PCR experiments, or viewed 8–20 h later for irg-1::GFP experiments. P. aeruginosa were heat-killed by incubating at 95°C for 30–40 minutes, and killing was confirmed by streaking onto LB plates to look for the absence of colonies.

Gene expression analysis

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and qRT-PCR were performed as described (Troemel et al., 2006). qRT-PCR primer sequences are available upon request. For all qRT-PCR experiments, each biological replicate was measured in duplicate and normalized to a control gene, which did not change expression upon conditions tested (nhr-23 for infection, cycloheximide and RNAi experiments; snb-1 for heat shock GFP experiments). The Pffafl method was used for quantifying data (Pfaffl, 2001). All qRT-PCR studies of P. aeruginosa induction were performed at 4 h post-inoculation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Disruption of translation and other host processes activates zip-2 immune signaling

P. aeruginosa uses Exotoxin A to block translation in the C. elegans intestine

Endocytosis is required for C. elegans transcriptional response to infection

zip-2 5′UTR contains uORFs and confers infection-mediated increase in ZIP-2 protein

Acknowledgments

We thank the CGC for some strains described in this paper. We thank R. Luallen for backcrossing and initial characterization of the zip-2(tm4248) strain. We thank A. Chisholm, E. Bier, M. Hansen, R. Luallen, A. Ma and S. Szumowski for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank M. Bakowski for help with the graphical abstract. We also thank D. McEwan, F. Ausubel, J. Melo, and G. Ruvkun for communicating results prior to publication and for helpful discussions. Supported by NIH T32 GM07240 training grant to T.L.D.; NSF predoctoral fellowship to K.M.B.; NIAID R01 AI087528, Moores Cancer Center grant, Searle Scholars Program, Ray Thomas Edwards Foundation, David & Lucille Packard Foundation fellowship to E.R.T.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information contains supplemental text, four figures, one table, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Auerbuch V, Golenbock DT, Isberg RR. Innate immune recognition of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III secretion. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5:e1000686. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM. Are innate immune signaling pathways in plants and animals conserved? Nature immunology. 2005;6:973–979. doi: 10.1038/ni1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Kock R, Fruth A, Bauwens A, Peters G, Karch H. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer L, Magoc L, Dejardin S, Cappillino M, Paquette N, Hinault C, Charriere GM, Ip WK, Fracchia S, Hennessy E, et al. Pathogen-derived effectors trigger protective immunity via activation of the Rac2 enzyme and the IMD or Rip kinase signaling pathway. Immunity. 2011;35:536–549. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RJ, Zhang Z. Histones, histone chaperones and nucleosome assembly. Protein Cell. 2010;1:607–612. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0086-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SG, Shurland DL, Meyerowitz EM, Bargmann CI, van der Bliek AM. A dynamin GTPase mutation causes a rapid and reversible temperature-inducible locomotion defect in C. elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:10438–10443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JD. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature. 2001;411:826–833. doi: 10.1038/35081161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Barbieri JT. Molecular mechanisms of the cytotoxicity of ADP-ribosylating toxins. Annual review of microbiology. 2008;62:271–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierking K, Polanowska J, Omi S, Engelmann I, Gut M, Lembo F, Ewbank JJ, Pujol N. Unusual regulation of a STAT protein by an SLC6 family transporter in C. elegans epidermal innate immunity. Cell host & microbe. 2011;9:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes KA, Dunbar TL, Powell JR, Ausubel FM, Troemel ER. bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:2153–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914643107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez J, Yaman I, Huang C, Liu H, Lopez AB, Komar AA, Caprara MG, Merrick WC, Snider MD, Kaufman RJ, et al. Ribosome stalling regulates IRES-mediated translation in eukaryotes, a parallel to prokaryotic attenuation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald D, Morris RE, Saelinger CB. Receptor-mediated internalization of Pseudomonas toxin by mouse fibroblasts. Cell. 1980;21:867–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana MF, Banga S, Barry KC, Shen X, Tan Y, Luo ZQ, Vance RE. Secreted Bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis are critical for induction of the innate immune response to virulent Legionella pneumophila. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1001289. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C, Werber D, Cramer JP, Askar M, Faber M, Heiden MA, Bernard H, Fruth A, Prager R, Spode A, et al. Epidemic Profile of Shiga-Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 Outbreak in Germany - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Zhang Y, Paupard MC, Lin SX, Hall DH, Hirsh D. Evidence that RME-1, a conserved C. elegans EH-domain protein, functions in endocytic recycling. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:573–579. doi: 10.1038/35078549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annual review of microbiology. 2005;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HR, Chen ZJ, Kunes S, Chang GD, Maniatis T. Endocytic pathway is required for Drosophila Toll innate immune signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:8322–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irazoqui JE, Troemel ER, Feinbaum RL, Luhachack LG, Cezairliyan BO, Ausubel FM. Distinct pathogenesis and host responses during infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ, Koyama S, Nakagawa A, Coban C, Akira S. Host innate immune receptors and beyond: making sense of microbial infections. Cell host & microbe. 2008;3:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Gabel HW, Kamath RS, Tewari M, Pasquinelli A, Rual JF, Kennedy S, Dybbs M, Bertin N, Kaplan JM, et al. Functional Genomic Analysis of RNA Interference in C. elegans. Science (New York, NY) 2005 doi: 10.1126/science.1109267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed EM, Vance RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Gallo RL. AMPed up immunity: how antimicrobial peptides have multiple roles in immune defense. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Matilainen O, Jin C, Glover-Cutter KM, Holmberg CI, Blackwell TK. Specific SKN-1/Nrf stress responses to perturbations in translation elongation and proteasome activity. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link CD, Cypser JR, Johnson CJ, Johnson TE. Direct observation of stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans using a reporter transgene. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999;4:235–242. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1999)004<0235:doosri>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, Rubartelli A, Sparvero LJ, Amoscato AA, Washburn NR, Devera ME, Liang X, Tor M, Billiar T. The grateful dead: damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and reduction/oxidation regulate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:60–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan DL, Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM. Host Translational Inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A Triggers an Immune Response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell host & microbe. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Approaching the asymptote: 20 years later. Immunity. 2009;30:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of essential cellular pathways stimulates microbial avoidance behavior, drug detoxification, and pathogen defense-related responses in C. elegans. Cell. 2012 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Miao EA, Mao DP, Yudkovsky N, Bonneau R, Lorang CG, Warren SE, Leaf IA, Aderem A. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:3076–3080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnicozzi M, Sawyer RT, Fenton MJ. Innate immunity in allergic disease. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:106–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TJ, Adepoju Y, Boyd D, Isberg RR. Minimization of the Legionella pneumophila genome reveals chromosomal regions involved in host range expansion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:14733–14740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111678108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Chaudhary VK, Pastan I, FitzGerald DJ. Processing of Pseudomonas exotoxin by a cellular protease results in the generation of a 37,000-Da toxin fragment that is translocated to the cytosol. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:20678–20685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JR, Ausubel FM. Models of Caenorhabditis elegans infection by bacterial and fungal pathogens. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;415:403–427. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-570-1_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol N, Link EM, Liu LX, Kurz CL, Alloing G, Tan MW, Ray KP, Solari R, Johnson CD, Ewbank JJ. A reverse genetic analysis of components of the Toll signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:809–821. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM. Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. Candida albicans infection of Caenorhabditis elegans induces antifungal immune defenses. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002074. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science (New York, NY. 1995;268:1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescigno M. The intestinal epithelial barrier in the control of homeostasis and immunity. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria NM, Huang JC, Dubery IA. Self/nonself perception in plants in innate immunity and defense. Self Nonself. 2010;1:40–54. doi: 10.4161/self.1.1.10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonetti PJ. To be or not to be a pathogen: that is the mucosally relevant question. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:8–14. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonetti PJ, Medzhitov R. Learning tolerance while fighting ignorance. Cell. 2009;138:416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Poetsch T, Ju J, Eyler DE, Dang Y, Bhat S, Merrick WC, Green R, Shen B, Liu JO. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation elongation by cycloheximide and lactimidomycin. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, Lee SS, Ausubel FM, Kim DH. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS genetics. 2006;2:e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Isberg RR, Portnoy DA. Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell host & microbe. 2009;6:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D, Mohr I. Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Robida-Stubbs S, Tullet JM, Rual JF, Vidal M, Blackwell TK. RNAi screening implicates a SKN-1-dependent transcriptional response in stress resistance and longevity deriving from translation inhibition. PLoS genetics. 2010:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaman I, Fernandez J, Liu H, Caprara M, Komar AA, Koromilas AE, Zhou L, Snider MD, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, et al. The zipper model of translational control: a small upstream ORF is the switch that controls structural remodeling of an mRNA leader. Cell. 2003;113:519–531. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngner JS, Stinebring WR, Taube SE. Influence of inhibitors of protein synthesis on interferon formation in mice. Virology. 1965;27:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdanovsky AG, Chiron M, Pastan I, FitzGerald DJ. Mechanism of action of Pseudomonas exotoxin. Identification of a rate-limiting step. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:21791–21799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang J, Shi J, Gong YN, Lu Q, Xu H, Liu L, Shao F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.