Abstract

Magnesium sulfate and nimesulide are commonly used drugs with reported neuroprotective effects. Their combination as stroke treatment has the potential benefits of decreasing individual drug dosage and fewer adverse effects. This study evaluated their synergistic effects and compared a low-dose combination with individual drug alone and placebo. Sprague-Dawley rats underwent 90 min of focal ischemia with intraluminal suture occlusion of the middle cerebral artery followed by reperfusion. The rats were randomly assigned to receive one of the following treatments: placebo, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; 45 mg/kg) intravenously immediately after the induction of middle cerebral artery occlusion, nimesulide (6 mg/kg) intraperitoneally before reperfusion, and combined therapy. Three days after the ischemia-reperfusion insult, therapeutic outcome was assessed by 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining and a 28-point neurological severity scoring system. Cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin E2, myeloperoxidase, and caspase-3 expression after treatment were evaluated using Western blot analyses and immunohistochemical staining, followed by immunoreactive cell analysis using tissue cytometry. Only the combination treatment group showed a significant decrease in infarction volume (10.93±6.54% versus 26.43±7.08%, p<0.01), and neurological severity score (p<0.05). Low-dose MgSO4 or nimesulide showed no significant neuroprotection. There was also significant suppression of cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin E2, myeloperoxidase, and caspase-3 expression in the combination treatment group, suggesting that the combination of the two drugs improved the neuroprotective effects of each individual drug. MgSO4 and nimesulide have synergistic effects on ischemia-reperfusion insults. Their combination helps decrease drug dosage and adverse effects. Combined treatment strategies may help to combat stroke-induced brain damage in the future.

Key words: in vivo studies, ischemia, middle cerebral artery occlusion, therapeutic approach, stroke

Introduction

Brain ischemia remains a major health problem with high morbidity and mortality despite decades of research. Complicated mechanisms such as energy deprivation, glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and ionic imbalance, oxidative/nitrosative stress, and apoptotic-like cell death are major mechanisms leading to cell death during ischemic insults (Lo, 2008; Mehta et al., 2007). These mechanisms demonstrate overlapping and redundant features, making the development of neuroprotective agents a difficult task. Many neuroprotective agents targeting specific mechanisms of ischemic injury are effective in preclinical trials, but fail in clinical trials (Ginsberg, 2008,2009).

Magnesium is critical to cellular energy metabolism (Lin et al., 2002). Inorganic magnesium ion (Mg2+) blocks synaptic transmission by preventing the release of neurotransmitters and blocking N-methyl-D-asparate (NMDA)-coupled calcium channels, thereby inhibiting calcium entry into neurons (Kass et al., 1988). Both in vitro (Greensmith et al., 1995) and in vivo experiments (Izumi et al., 1991; Marinov et al., 1996) suggest that magnesium ions reduce the neuronal damage brought about by ischemia or excitatory amino acids. But despite favorable results in preclinical studies, the neuroprotective effects of Mg2+ are still controversial. Differences in dosage, time of administration, and hypothermia are contributing factors to the conflicting results (Meloni et al., 2006). Sufficient doses should be given as early as possible to block the deleterious cascade of cellular injury mechanisms induced by ischemia. Many studies showed a positive neuroprotective effect of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) at a dosage of 90 mg/kg administered before or immediately after the onset of ischemia. It is well known that the adverse effects of MgSO4, such as cardiovascular depression, suppression of respiration, and central nervous system depression, are associated with rapid bolus infusions. To decrease the effective therapeutic dose and adverse effects of MgSO4, combination with another drug targeting the downstream pathophysiologic events is a reasonable approach.

Ischemic injury also triggers inflammatory cascades in the parenchyma that further amplify tissue damage (Allan and Rothwell, 2001; Barone and ad Feuerstein, 1999). Numerous studies have found a dramatic increase in cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression following ischemia. Increased COX-2 activity may induce increased arachidonic acid levels, which may have direct excitotoxic effects (Katsuki and Okuda, 1995). Free radicals produced by COX-2 while converting arachidonic acid to eicosanoids may contribute to ischemic neuronal damage (Katsuki and Okuda, 1995). Prostaglandins may potentiate post-ischemic inflammation by increasing edema and by allowing entry of proinflammatory cells into the brain (Ferreira, 1972). These findings suggest that COX-2 has an important role in ischemic brain injury.

The neuroprotective effect of COX-2 inhibitors has been widely studied in animal models of ischemic insults (Candelario-Jalil and Fiebich, 2008). Nimesulide is one of the few COX-2 inhibitors that has been extensively studied in different models of brain ischemia. Findings indicate that nimesulide may be a promising neuroprotective agent. It is a preferential COX-2 inhibitor widely used clinically as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. The recommended dose for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is 3–6 mg/kg per day for adult patients. Adverse reactions include gastrointestinal damage, hepatic and renal toxicity, and cardiovascular complications (Rainsford, 2006). Several studies report significant neuroprotective effects of nimesulide at a dosage of 12 mg/kg (Candelario-Jalil and Fiebich, 2008; Candelario-Jalil et al., 2004,2007). However, a daily dose of 12 mg/kg increases the risk of adverse drug reactions (Singla et al., 2000).

Combinations of established neuroprotective agents with distinct mechanisms has been considered in stroke therapy. Combination therapy may reduce the dose of individual agents, with a consequent reduction in the undesirable adverse effect of toxicity. The current study used an ischemia and reperfusion model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) to test the synergism of MgSO4 and nimesulide at half their usual dose. The neuroprotective effects of three protocols, MgSO4 alone, nimesulide alone, and a combination of both, were evaluated.

Methods

Animals

The National Cheng Kung University Animal Ethics Committee approved all of the experimental procedures, and appropriate measures were taken to minimize the pain and distress of the animals used in this study. The animals were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of National Cheng Kung University and housed on bagasse bedding in groups of three in cages. The animals were given rodent pellet chow and water ad libitum. One hundred and fifty adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 220–250 g were used.

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

Anesthesia was inducted with 5% isoflurane mixed with 70% N2O and 30% O2 in an induction chamber and regulated as necessary. Surgical-depth anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane. Rectal temperature was monitored by digital thermometer. MCAO was induced by using an occluding intraluminal suture as previously described (Longa et al., 1989; Zhang et al., 2003). Briefly, an area of skull 2 mm posterior and 6 mm lateral to the bregma was decorticated. The tip of a laser doppler probe (Oxylab LDF™; Oxford Optronix Ltd, Oxford, U.K.) was positioned on the decorticated skull window to monitor regional cerebral blood flow (laser doppler flow, LDF).

A 22-mm-long 4-0 nylon thread, heat treated to produce a dilated segment 4 mm in length and 0.28 mm in diameter was used as an occluder. The occluder was inserted through the arteriotomy into the internal carotid artery and advanced until the LDF dropped to less than 30% of baseline, indicating MCAO. Cerebral blood flow was monitored for 5 min to ensure maintenance of cerebral blood flow below 30% of baseline. After wound closure, the rats were allowed to awaken from anesthesia in a warm cage. Anesthetic time was limited to 20 min. This short anesthetic period minimized the influence of anesthesia on the outcome of MCAO.

Following 90 min with the occluder in place, the neurologic status of the rats was examined. Rats without front limb asymmetry when suspended by their tail were regarded as failed MCAO and excluded from the experiments. For reperfusion, the nylon occluder was withdrawn and cerebral blood flow was monitored. Rats that failed to regain more than 80% of basal LDF were regarded as failed reperfusion and were excluded. During the surgical course, room temperature surrounding the operative bench was kept around 28±2°C with an electrical heater. The rats were allowed to self-regulate their body temperature.

Drugs

Standard-strength nimesulide was provided by Lotus Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taiwan, R.O.C. Nimesulide was dissolved in 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) as vehicle for intraperitoneal injection. Ten percent MgSO4 was purchased from Taiwan Biotech Co., Ltd., Taiwan, R.O.C., and was diluted to 5% with normal saline. Normal saline and 2% PVP were used as placebos in the experiments.

Experimental groups

Rats weighing 220–250 g were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: group SVe, treated with placebo (0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP); group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg. MgSO4 or normal saline was injected intravenously immediately after MCAO. Nimesulide or PVP was injected intraperitoneally just before reperfusion. Five cohorts of rats (n=30 for each cohort) were used in the evaluation of infarct volume, brain edema evaluation, Western blot analysis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Neurobehavioral testing

Neurological outcome was evaluated using a Neurological Severity Score (NSS) developed by Clark and associates (Clark et al., 2000). At 24 and 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion, the animals were scored for neurologic deficits by a 28-point scoring system. Scores were assigned to each animal (0- to 4-point scale) for each of seven functional tests: gait, body symmetry, climbing, turning behavior, front leg extension, compulsory circling, and sensory response. Two investigators blinded to the treatment groups independently scored the animals, and the higher score of the two observations was taken as the final score of the rat.

Infarct volume assessment

Quantification of infarct volume was performed as previously reported (Lin et al., 1993; Swanson et al., 1990). Briefly, the animals were euthanatized under deep anesthesia and the brains were removed, frozen, and coronally sectioned into seven 2-mm-thick slices (from rostral to caudal, first to seventh) using a rat brain matrix (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The brain slices were incubated for 30 min in a 2% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C and fixed by immersion in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Seven TTC-stained brain sections per animal were digitalized using a color flatbed scanner (Microtek Scanmaker 6100) within 3 days. The digital images were analyzed using an image processing program (ImageJ ver. 2.1; National Institutes of Health [NIH]). An investigator blinded to treatment group performed the measurements of infarction volume. The unstained area of the fixed brain section was defined as the infarction area, and its margin was outlined manually. Infarction areas and total hemispheric areas were calculated separately for each coronal slice. Total infarct volume was calculated by multiplying the infarction area by the slice thickness and summing the volume of the six slices. The effect of brain edema was compensated for by the indirect method proposed by Swanson and colleagues (Swanson et al., 1990). Infarction volume was calculated by the formula: percentage of infarction=(LT – RN)×100/RT, where LT was the total left hemisphere volume, RN was the non-infarcted volume in the right hemisphere, and RT was the total right hemisphere volume.

Evaluation of cerebral edema

Forty-eight hours after MCAO, cerebral edema was determined by measuring brain water content according to the wet-dry method. The rats were euthanized and the brains were immediately removed and placed on a frozen plate. The brains were dissected from the midline. The samples were immediately weighted to obtain the wet weight. The samples were then dried in a desiccating oven at 80°C for 24 h and weighed again to obtain the dry weight. The percentage of water content in the hemisphere was calculated by the formula: % water content=(wet weight – dry weight) ×100/wet weight. Differences in water content between the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres are presented as Δ% water content (Hatashita et al., 1998).

Western blotting

Western blotting was preformed following the protocol previously described by Tsai and associates (Tsai et al., 2010). The middle third of the right hemisphere was dissected out. The dissected brain samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen with denaturing lysis buffer. The total protein in the brain sample was extracted. The protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equivalent amounts of protein were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 4% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween-20 (TTBS), and incubated with the primary antibody (rabbit anti-COX-2 Ab, 1:10,000, or goat anti-rat caspase-3 Ab, 1:1000) at 4°C overnight. After three washing steps with TTBS, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary Ab (1:3000; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h at room temperature. The signal was analyzed. Amounts of caspase-3 and COX-2 were expressed as arbitrary units. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) concentrations in the brain tissue were measured 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion. Brain samples were weighed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. PGE2 and MPO concentrations in the supernatant were measured by a specific ELISA-based assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (PGE2, Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI; MPO, HyCult Biotechnology, Uden, Netherlands).

Brain section preparation

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with heparinized saline followed by 300 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and post-fixed 4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Coronal sections (5-μm thick) were taken every millimeter from 2.2 to –6.3 mm relative to the bregma.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC analysis was performed following a previously described protocol (Tsai et al., 2007). The sections were de-paraffinized with xylene and hydrated in a graded ethanol series to distilled water. Each series was reacted with rabbit monoclonal IgG against COX-2 (1:200 dilution), MPO (1:200 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.), and activated caspase-3 (1:200 dilution; Imgenex, San Diego, CA), in humid chambers overnight at 4°C to reveal the immunoreactions. After incubation with the primary antibody, the sections were developed with the Dako Envision Detection System (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 60 min. Diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen to visualize the sites expressing immunoreactivity. Finally, the sections were counterstained by hematoxylin and eosin to better reveal histologic details, dehydrated, and mounted. The sections were processed in parallel under standardized conditions for immunostaining to minimize variability in labeling conditions.

Image analysis and cell counting

Sections taken from 0.26 mm posterior to the bregma were analyzed. Images were digitized with an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) BX-50 microscope (20× objective) with an Optronics microscope camera. Image analysis software (ImageJ) was used for the analysis of immunoreactivity in the histologic brain sections. The inner boundary zone of the infarction was defined as inner 1.0-mm border of infarction (Supplementary Fig. 1; see online supplementary material at http://www.liebertonline.com; Kitagawa et al., 1998; Li et al., 1995; Suzuki et al., 2005). Two areas of interest (AOIs; 0.25 mm2 each) were chosen in the inner boundary zone of infarction. The number of immunoreactive cells labeled for COX-2, MPO, and active caspase-3 in the AOIs were calculated. The amounts of active caspase-3 and COX-2 immunoreactive cells were expressed as percentages of immunoreactive cells in all cells. Numbers of MPO-immunoreative cells in the AOIs were calculated. The staining intensity was quantified by tissue cytometry using HistoQuest analysis software (TissueGnostics, Tarzana, CA). Antibody-mediated chromogen stain and the counter-stain were separated by HistoQuest software and displayed in scattergrams.

Statistical analysis

Neurological Severity Scores were analyzed by non-parametric tests for independent groups (i.e., the Kruskal-Wallis/Mann-Whitney U test). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's protected least-significant difference (LSD) post-hoc comparison was used to evaluate differences between groups. Dunnett's post-hoc t-test (Dunnett's test) was used to evaluate the difference between the therapeutic groups and the placebo group. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Changes of LDF signal and body temperature during MCAO and reperfusion

The successful rate of surgery for MCAO and reperfusion was 74.6%, with 112 rats included for further evaluation. Changes of LDF signals and body temperature during MCAO and reperfusion are shown in Table 1. Decrease and restoration of local cerebral flow as detected by LDF after MCAO and reperfusion had no significant difference between groups (p>0.05). All rats had post-ischemic hyperthermia in the present study. Elevation of anal temperature after MCAO and reperfusion had no significant difference between groups (p>0.05).

Table 1.

Changes of LDF Signal and Temperature during MCAO and Reperfusion

| Treatment group | %LDF after MCAO | %LDF after reperfusion | BT after MCAO | BT after reperfusion | BT elevation 90 min after MCAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVe (n=25) | 23.7±1.9 | 107.2±5.0 | 36.89±0.18 | 38.58±0.09 | 1.67±0.18 |

| MgVe (n=29) | 23.6±1.3 | 101.2±5.1 | 37.23±0.10 | 38.66±0.08 | 1.43±0.13 |

| SNi (n=28) | 24.1±1.5 | 94±4.6 | 37.37±0.13 | 38.76±0.10 | 1.40±0.16 |

| MgNi (n=30) | 22.8±1.1 | 100.8±5.8 | 37.17±0.09 | 38.73±0.08 | 1.56±0.12 |

Changes of LDF signal and body temperature (BT, °C) are summarized. Changes of LDF signal are presented as percentage of baseline signal (%LDF). All data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean.

Groups: group SVe, treated with placebo (0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP); group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg.

LDF, laser doppler flow; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; MgSO4 magnesium sulfate.

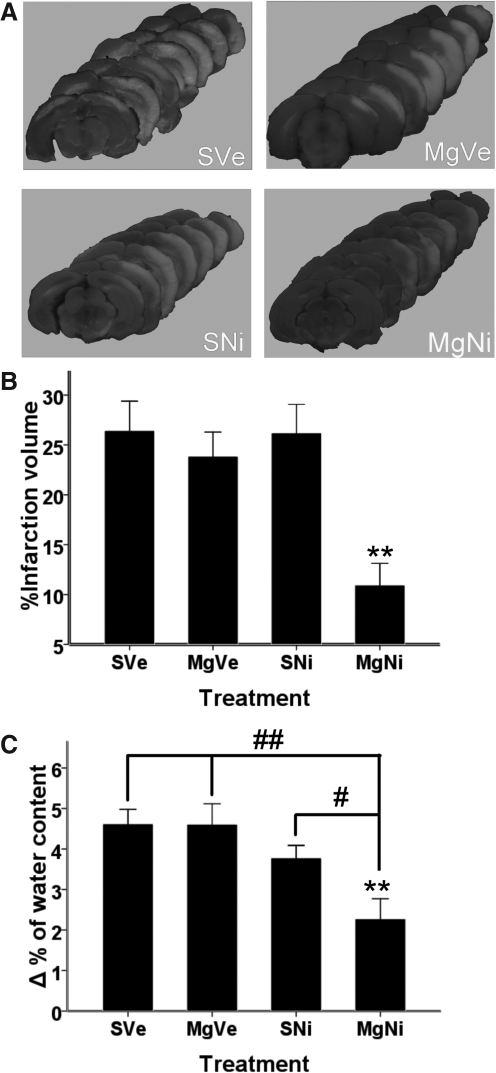

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide treatment on infarct volume

Infarct volume was assessed by TTC staining at 72 h of reperfusion after 90 min of MCAO. A single dose of MgSO4 did not decrease infarction volume, and a single dose of nimesulide also had no neuroprotective effect. There was attenuated total infarction volume, from 26.43±7.80% in the placebo group to 10.93±6.54% in the combination treatment group (p=0.007 by Dunnett's test; Fig. 1A and B). There was also a significant decrease in infarction volume in the combination treatment group compared to the groups that received either MgSO4 or nimesulide alone (p=0.001 and p=0.001, respectively, by LSD test).

FIG. 1.

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide on infarct volume and brain edema. (A) Representative pictures of TTC staining. (B) Percentage of infarction volume shown as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM; n=7–8). Combined treatment with MgSO4 and nimesulide significantly attenuated total infarction volume (**p<0.01 by Dunnett's test), whereas MgSO4 or nimesulide alone had no statistically significant effect on attenuating infarct volume. (C) Brain edema was evaluated by wet-dry weight (n=5–6). Differences in water content between the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres (Δ% of water content) 48 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury are represented as mean±SEM. Only combination treatment significantly attenuated brain edema (p=0.002 by Dunnett's test; **p<0.01). Brain edema in the combination treatment group was significantly reduced compared to the groups treated with MgSO4 alone and nimesulide alone (p=0.001 and p=0.024, respectively, by Fisher's protected least-significant difference test; #p<0.05; ##p<0.01; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; TTC, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg).

Effect of MgSO4 and nimesulide treatment on post-ischemia brain edema

According to previous publications, the disruption of the blood–brain barrier after ischemia is maximal at 48 h (Candelario-Jalil et al., 2007). The difference in water content in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemisphere (Δ% of water content) 48 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury was evaluated by wet-dry weight. Combined treatment with MgSO4 and nimesulide significantly attenuated post-ischemia brain edema after MCAO with 48 h of reperfusion, compared to the placebo group (p=0.023 by Dunnett's test). Treatment with nimesulide or MgSO4 alone showed no effect on lessening brain edema (Fig. 1C).

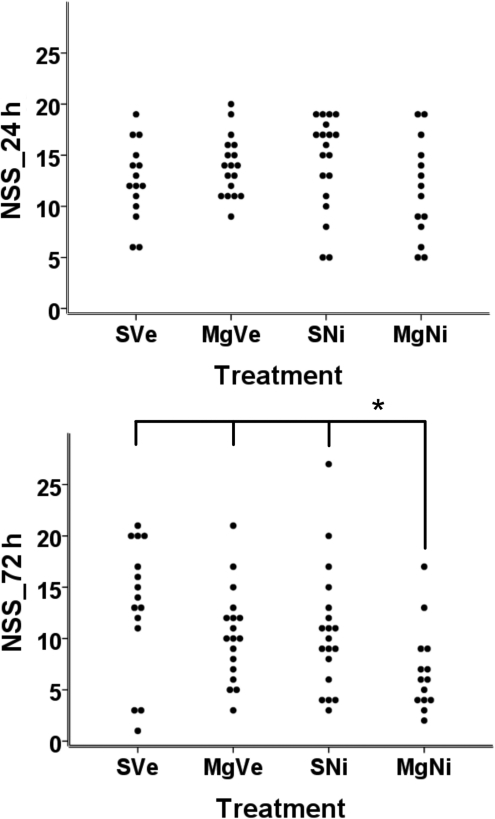

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide treatment on functional outcome

Scattergrams of NSS per treatment group are presented in Figure 2. Twenty-four hours after ischemia-reperfusion, there was no significant difference in neurological severity score among the groups (Fig. 2A). Seventy-two hours after MCAO, the combination treatment group showed significantly reduced neurologic deficit compared to groups treated with placebo, MgSO4 only, and nimesulide only. (p=0.015, 0.04, and 0.021 respectively; Mann-Whitney test) (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Effect of combined treatment on functional outcome after MCAO with reperfusion. Scattergrams of Neurological Severity Score (NSS) per treatment group are shown (n=15–20). (A) There were no significant differences in NSS for all groups 24 h after MCAO. (B) Combined treatment significantly reduced the neurologic deficit seen after MCAO with 72 h reperfusion compared to groups treated with vehicle, MgSO4 only, and nimesulide only (p=0.015, 0.04., and 0.021, respectively, by; Mann-Whitney U test; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg).

Consistent with decreasing infarction volume after treatment with the combination protocol, neurological outcome in the combination treatment group also showed significant improvement compared to the other groups. There was significantly reduced infarction volume, attenuated brain edema, and improved functional outcome, suggesting that combination treatment improved the neuroprotective effect of each individual drug.

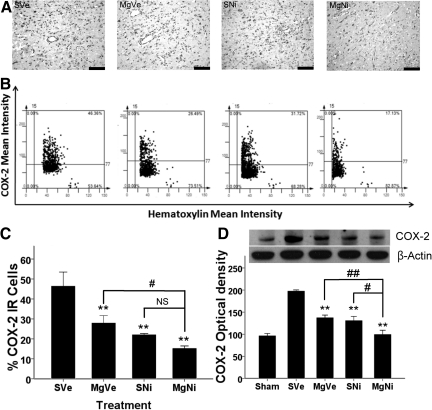

Effect of MgSO4 and nimesulide treatment on COX-2 expression in the inner boundary zone of infarction

Induction of COX-2 expression in neurons was most obvious in the penumbra. Seventy-two hours after MCAO with reperfusion, the number of COX-2-immunoreactive (IR) cells in the inner boundary of the ischemia of the frontal cortex was significantly reduced in all groups that received treatment compared to the placebo group (p<0.001 by Dunnett's test). Only the difference in the amount of COX-2-expressing cells between the groups receiving the combined treatment and MgSO4 was statistically significant (p<0.05 by LSD test). However, the difference between the combination treatment group and the nimesulide-only group was not statistically significant (Fig. 3), which suggested that the synergistic effect of MgSO4 and nimesulide was not significant in the penumbra area.

FIG. 3.

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide on COX-2 expression 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for COX-2 (scale bars=100 μm). (B) Representative images of tissue cytometry using TissueQuest software. COX-2-immunoreactive (IR) positive and negative cells were counted and the signal intensity was quantified. (C) The amount of COX-2 IR cells in the inner boundary zone of infarction was recorded as the percentage of IR cells in all cells (n=5 per group). Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). All treatments suppressed COX-2 protein expression compared to the placebo group (p<0.001 for MgNi; p=0.007 for SNi; p=0.021 for MgVe; **p<0.01 by Dunnett's test). Combined treatment improved the effect of MgSO4 (p=0.02 by least-significant difference [LSD] test). The difference between groups receiving nimesulide alone or combined treatment was not statistically significant (p=0.163; #p<0.05; NS, not significant). (D) Western blot analysis of brain tissue for COX-2 protein 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Single or combined treatments significantly reduced COX-2 protein expression 72 h after MCAO with reperfusion (n=4–5; **p<0.001 by Dunnett's test). Data are presented as mean±SEM. Combined treatment showed improved effects on reducing COX-2 expression compared to treatment with MgSO4 or nimesulide alone (p=0.004 and 0.011, respectively, by LSD test; #p<0.05; ##p<0.01; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone).

Effects of combined treatment on suppressing COX-2 expression in brain tissue

Expression of COX-2 protein 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion insult was evaluated by Western blot analysis of brain tissue. COX-2 protein expression was significantly reduced in all treatment groups compared to the placebo group (p<0.001 by Dunnett's test; Fig. 3D). The combination treatment group had a statistically significant reduction in COX-2 protein expression compared to the MgSO4-only or nimesulide-only groups (p=0.004 and 0.011, respectively, by LSD test).

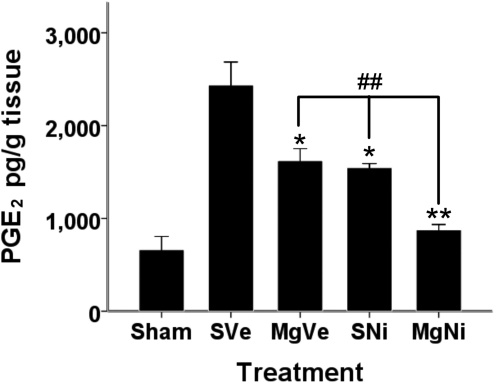

Effect of combined treatment on PGE2 expression after ischemic infarction

PGE2 concentration in brain tissue was significantly reduced by administration of either MgSO4 or nimesulide (p=0.001 by Dunnett's test; Fig. 4). Combined treatment improved the effect of individual drugs. PGE2 expression in the combination treatment group was significantly reduced compared to groups treated with MgSO4 alone and nimesulide alone (p=0.001 and 0.003, respectively, by LSD test).

FIG. 4.

ELISA of PGE2 expression in brain 72 h after ischemic-reperfusion injury. The expression of PGE2 after ischemic-reperfusion injury is shown here (n=4–5). Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. PGE2 concentrations in the brain tissue were significantly reduced by both MgSO4 or nimesulide alone (*p<0.01, **p<0.001 by Dunnett's test). Combined treatment significantly reduced the PGE2 concentration compared to the group treated with nimesulide only (##p<0.01; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg).

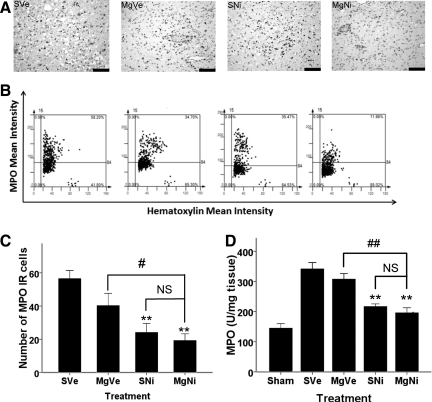

Effect of combined treatment on MPO expression

Immunohistochemistry showed that the amount of MPO IR cells in the inner boundary zone of infarction decreased in groups received nimesulide alone or combined with MgSO4 (p=0.004 and p=0.001, respectively, by Dunnett's test; Fig. 5). Treatment with MgSO4 alone showed no effect on MPO suppression (p=0.144 by Dunnett's test).

FIG. 5.

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide on MPO expression 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for MPO (scale bars=100 μm). (B) Representative scatterplots of tissue cytometry using TissueQuest software. MPO immunoreactive-(IR) positive and negative cells were counted, and the signal intensity was quantified. (C) Immunohistochemistry (n=5 per group) showed the number of MPO IR cells in the inner boundary zone of infarction. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. Data showed that MPO IR cells significantly decreased in nimesulide only and combination (p=0.004 and 0.001 respectively Dunnett's test). **p<0.01;. Differences between the combination treatment group and nimesulide only group was not significant, but the difference between the MgSO4 only and the combination treatment groups was significant (#p<0.05, NS: p>0.05). (D) ELISA of MPO expression 72 hours after ischemia-reperfusion. (n=5 per group). MPO concentration in brain tissue is presented as mean±standard error of the mean. MPO expression was not suppressed by treatment with MgSO4 alone. Treatment with nimesulide alone or combined with MgSO4 showed significant suppression compared to the placebo group (**p<0.01 by Dunnett's test), but the difference between these two groups was not significant (##p<0.01 by least-significant difference test; NS, not significant; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg).

ELISA of MPO in brain tissue showed that treatment with MgSO4 alone did not attenuate MPO expression (Fig. 5D). Treatment with nimesulide alone or combined with MgSO4 significantly suppressed MPO expression compared to the placebo group (p=0.001 by Dunnett's test), but the difference between these two groups was not significant.

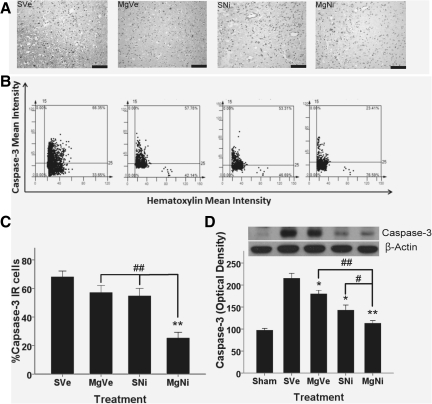

Caspase-3 expression in brain tissue

Immunohistochemistry of the inner boundary zone of infarction showed that the presence of caspase-3-IR cells could be significantly suppressed only in the combination treatment group (p<0.001 by Dunnett's test; Fig. 6). Although the amount of caspase-3-IR cells decreased in the nimesulide-alone group, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.074 by Dunnett's test), whereas treatment with MgSO4 alone had no effect. Western blot analyses showed that the expression of activated caspase-3, indicating progression of apoptosis, was attenuated in the groups treated with MgSO4 alone, nimesulide alone, and the combination protocol (p=0.038, 0.001, and <0.001, respectively, by Dunnett's test; Fig. 6D). The differences between the groups treated with individual drugs and the combination treatment group were also significant (p=0.001 versus the MgSO4 group, and p=0.05 versus the nimesulide group by LSD test).

FIG. 6.

Effect of combined MgSO4 and nimesulide on caspase-3 expression 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury. (A) Immunohistochemistry in the inner boundary zone of infarction for caspase-3 (scale bars=100 μm). (B) Representative images of tissue cytometry using TissueQuest software. Caspase-3-immunoreactive (IR) positive and negative cells were counted and the signal intensity was quantified. (C) The amount of caspase-3-IR cells were recorded as percentages of IR cells in all cells, and are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM; n=5 per group). The amount of IR cells in the inner boundary zone of infarction was significantly decreased only in the combination treatment group (**p<0.01 by Dunnett's test). The difference between the nimesulide-only and the combination treatment group was also statistically significant (##p<0.01 by least-significant difference test). (D) Western blot analysis of caspase-3 expression in brain tissue 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury (n=5 per group). Data are presented as mean±SEM. Administration of MgSO4 alone or nimesulide alone significantly attenuated caspase-3 expression in brain tissue (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 by Dunnett's test). The combination treatment significantly decreased caspase-3 expression in brain tissue after MCAO with reperfusion (MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MgSO4 magnesium sulfate; group SVe, treated with placebo [0.25 mL normal saline and 0.25 mL 2% PVP]; group MgVe, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and 0.25 mL 2% PVP; group SNi, treated with 0.25 mL normal saline and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; and group MgNi, treated with MgSO4 45 mg/kg and nimesulide 6 mg/kg; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone).

Discussion

Trying to find a single drug that acts against the pathologic events after stroke may be difficult because of the complicated and inter-chelated path of physiologic changes seen after ischemic insults. A combination of established neuroprotective agents with distinct mechanisms of action has been considered in stroke therapy. Combination therapy may reduce the doses needed of individual agents, with consequent reductions in undesirable adverse effects and toxicity. Furthermore, the additive or synergistic effects of combined therapy may help attain outcomes that are better than those achieved with either agent alone.

The present study combined two potential neuroprotectants, MgSO4 and a COX-2 inhibitor, to treat ischemic stroke in an animal model. The dosage used for each individual drug was reduced to half of the dosage usually used in animal models in order to examine the synergism between the two agents. The data show that intravenous administration of MgSO4 45 mg/kg immediately after MCAO, and administration of a COX-2 inhibitor (nimesulide, 6 mg/kg) intraperitoneally before reperfusion work synergistically to attenuate infarction volume and improve the functional outcome after 90 min of MCAO followed by 72 h of reperfusion.

The neuroprotective potential of MgSO4 remains controversial. Of 13 studies examining the neuroprotective effect of Mg2+ following focal cerebral ischemia, 8 reported significant neuroprotective activity of Mg2+. Different dosages, routes, and times of administration, and post-ischemia hypothermia are all posited as possible causes of the discrepancies seen in the findings (Meloni et al., 2006). The most popular protocol of MgSO4 administration is 90 mg/kg given immediately after or before the onset of ischemia. Only two studies using MgSO4 dosages less than 90 mg/kg reported significant neuroprotective effects of Mg2+ (Kass et al., 1998; Kinoshita et al., 2001). Hypothermia has been proposed as an important confounding factor in evaluating the neuroprotective effects of Mg2+. Izumi and associates (Izumi et al., 1991) showed that Mg2+-treated (MgCl2, 1 mmol/kg) animals experienced a drop of 0.5°C in rectal temperature when measured 1.5 h after transient focal ischemia. In the present study, body temperature measured 1.5 h after MCAO showed that hypothermia did not develop in rats receiving low-dose MgSO4 (0.275 mmol/kg). On the contrary, hyperthermia developed in all groups, though the inter-group differences were not significant. It was proposed that hypothalamic ischemia during intraluminal MCAO may induce hyperthermia, but the development of hyperthermia had no influence on infarction volume (Li et al., 1999). No influence of hypothermia on neuroprotective effects was observed in the present study.

The neuroprotective effect of Mg2+ is influenced by its bio-availability in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; Meloni et al., 2006). Mg2+ is an important ion for maintaining cell function, and is tightly regulated in the CSF. It has been found that after intravenous or intramuscular doses that increase serum Mg2+ concentrations by 50–100%, the CSF total magnesium concentration rises by only approximately 20% (Fuchs-Buder et al., 1997; Thurnau et al., 1987). It is thus reasonable to propose that MgSO4 be given as a bolus to achieve therapeutic concentrations in the CSF. However, bolus administration of MgSO4 increases the risk of adverse effects, such as cardiovascular depression, respiratory suppression, and central nervous system depression. Combined therapy with a second agent to decrease the therapeutic dose and adverse effects is thus desirable. Ischemia triggers a deleterious cascade of cellular injury. Some biochemical reactions, such as free radical formation and post-ischemic inflammation, are not affected by Mg2+. Early bolus administration of Mg2+ may partially block the cascade of cell injury originating upstream, but its effect may be overwhelmed by downstream biochemical reactions. Combination with agents targeting the downstream mechanisms may help enhance the neuroprotective effect of Mg2+. The neuroprotective effects of COX-2 inhibitors has been widely studied in animal models of ischemic insults (Candelario-Jalil and Fiebich, 2008). Several studies report significant neuroprotective effects of nimesulide at a dosage of 12 mg/kg (Candelario-Jalil et al., 2004,2007). However, a daily dose of 12 mg/kg increases the risk of adverse drug reactions (Singla et al., 2000). The neuroprotective effect of nimesulide in clinically relevant doses (3–6 mg/kg) has been studied using global ischemia models. Candelario-Jalil and colleagues (Candelario-Jalil et al., 2007; Candelario-Jalil, 2008) showed that delayed treatment with nimesulide reduces oxidative stress following global ischemic brain injury. Wakita and associates (Wakita et al., 1999) showed that nimesulide attenuates white matter damage in chronic cerebral ischemia. In the present study, the neuroprotective effect of nimesulide at 6 mg/kg following MCAO with reperfusion was not significant. The discrepancy may be due to different animal models and times of drug administration.

The current data show that neither nimesulide 6 mg/kg administered immediately before reperfusion, nor MgSO4 45 mg/kg administered immediately after MCAO had statistically significant neuroprotective effects. Though our sample size was not large enough to conclude that the individual drugs are ineffective in the treatment of ischemic stroke, the combination of the two drugs at low dosages dramatically improved the neuroprotective effect of each drug, and decreased the risk of development of dosage-related adverse effects.

Expression of COX-2 in the brain is regulated by NMDA-dependent synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Miettinen and colleagues have shown that induction of COX-2 expression after focal brain ischemia is regulated through NMDA receptors and phospholipase A2 (Miettinen et al., 1997). Cortical induction of COX-2 can be reduced by NMDA receptor antagonists (Yamagata et al., 1993). MgSO4 is an intrinsic NMDA receptor antagonist, and can attenuate COX-2 expression 72 h after focal ischemia. Several studies also showed that COX-2 expression may be influenced by its downstream product, PGE2, suggesting that COX-2 inhibitors may suppress COX-2 expression (Faour et al., 2001; Minghetti et al., 1997; Murakami et al., 1997). In the current study, both MgSO4 and nimesulide attenuated COX-2 expression. The combination of both drugs enhances their respective effects by inhibiting different points of the cascade regulating COX-2 expression. In the present study, IHC was used to evaluate COX-2 expression in the penumbra, whereas samples for Western blotting included both the core of infarction and the penumbra. The effect of combination treatment on COX-2 suppression was less significant by IHC than by Western blotting. This discrepancy may result from differences in sampling areas. There is also increasing evidence that COX-2 exerts its neurotoxic effect through prostanoids, PGE2 in particular (FitzGerald, 2003; Manabe et al., 2004; Miettinen et al., 1997). Our data show that PGE2 concentrations 72 h after ischemia-reperfusion, consistent with COX-2 expression, can be suppressed by MgSO4 or nimesulide alone, but their combination significantly improves the effects of the individual drugs.

Post-ischemic inflammation is an important contributor to the progression of ischemic insults (Barone and Feuerstein, 1999; Chamorro and Hallenbeck, 2006). Infiltration of inflammatory cells, followed by generation of toxic substances such as ROS and matrix metalloproteinase, is important to the progression of post-ischemic inflammation (Hartl et al., 1996). COX-2 may enhance inflammation through products of prostanoid synthesis, PGE2 and free radicals. MPO is a key component in azurophilic granules in neutrophils, and is an important biochemical marker for neurophils. MPO-mediated radicalization of molecules induces apoptosis and nitro-tyrosination of proteins (Breckwoldt et al., 2008). In the present study, MPO protein expression increased after ischemia-perfusion insults. Administration of MgSO4 immediately after MCAO did not attenuate MPO expression, while nimesulide given before reperfusion attenuated MPO elevations in brain tissue. The combination of the two drugs showed no improvement in MPO suppression. These data suggest that MgSO4 cannot inhibit infiltration of neutrophils. Thus MgSO4 improves the neuroprotective effect of nimesulide through mechanisms other than reducing inflammation.

In the penumbra of ischemia, apoptotic cell death is an important contributor to the expansion of the ischemic infarct. PGE2 induces apoptotic cell death in rat cortical and hippocampal neurons (Takadera and Ohyashiki, 2006; Takadera et al., 2002). Suppression of COX-2 and PGE2 expression may attenuate the progression of apoptosis and decrease the infarction volume. Decreased expression of caspase-3 in brain tissue supports the anti-apoptotic effect of the combined protocol. Suppression of caspase-3 is more prominent in the penumbra, as examined using IHC, consistent with the concept that the penumbra is the target for neuroprotection after ischemic insults (Lo, 2008).

In conclusion, the present study evaluates the therapeutic effect of a novel combination treatment for ischemic infarction. Combined MgSO4 and nimesulide at reduced dosages have neuroprotective effects, with improved functional outcomes consistent with decreased infarction volume. Though the exact mechanisms of synergism were not clarified in this study, decreased COX-2 and PGE2 expression, attenuated neutrophil infiltration, and suppressed progression of caspase-3-mediated apoptosis suggest anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of this protocol. The low dosages of the drugs used in the combination treatment also decrease the risk of dosage-related adverse effects. However, the dosages and times of administration used in this study were established according to previous studies. The optimal dosages and therapeutic windows of this combination protocol deserve further evaluation. Our combination treatment represents a potential therapy for ischemic stroke and has valuable clinical relevance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wan-Lin Chao, Ya-Chun Hsiao, and Chin-Lan Jua for technical support. We are also grateful to Dr. Kuen-Jer Tsai and Yi-Ru Gu for the image acquisition and analysis from the FACS-like Tissue Cytometry in the Research Center of Clinical Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Hospital Medical Center. These studies were supported by Program Project Grant NCKUH-9803016 of the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Allan S.M. Rothwell N.J. Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:734–744. doi: 10.1038/35094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone F.C. ad Feuerstein G.Z. Inflammatory mediators and stroke: new opportunities for novel therapeutics. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:819–834. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckwoldt M.O. Chen J.W. Stangenberg L. Aikawa E. Rodriguez E. Qiu S. Moskowitz M.A. Weissleder R. Tracking the inflammatory response in stroke in vivo by sensing the enzyme myeloperoxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:18584–18589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803945105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E. Fiebich B.L. Cyclooxygenase inhibition in ischemic brain injury. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:1401–1418. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E. Gonzalez-Falcon A. Garcia-Cabrera M. Leon O.S. Fiebich B.L. Post-ischaemic treatment with the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor nimesulide reduces blood-brain barrier disruption and leukocyte infiltration following transient focal cerebral ischaemia in rats. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:1108–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E. Gonzalez-Falcon A. Garcia-Cabrera M. Leon O.S. Fiebich B.L. Wide therapeutic time window for nimesulide neuroprotection in a model of transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Brain Res. 2004;1007:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E. Nimesulide as a promising neuroprotectant in brain ischemia: New experimental evidences. Pharmacol. Res. 2008;57:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro A. Hallenbeck J. The harms and benefits of inflammatory and immune responses in vascular disease. Stroke. 2006;37:291–293. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000200561.69611.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W.M. Rinker L.G. Lessov N.S. Hazel K. Hill J.K. Stenzel-Poore M. Eckenstein F. Lack of interleukin-6 expression is not protective against focal central nervous system ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31:1715–1720. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faour W.H. He Y. He Q.W. de Ladurantaye M. Quintero M. Mancini A. Battista J.A.D. Prostaglandin E2 regulates the level and stability of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in interleukin-1 beta-treated human synovial fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31720–31731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S.H. Prostaglandins, aspirin-like drugs and analgesia. Nature New Biol. 1972;240:200–203. doi: 10.1038/newbio240200a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald G.A. COX-2 and beyond: approaches to prostaglandin inhibition in human disease. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2003;2:879–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Buder T. Tramer M.R. Tassonyi E. Cerebrospinal fluid passage of intravenous magnesium sulfate in neurosurgical patients. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 1997;9:324–328. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg M.D. Current status of neuroprotection for cerebral ischemia. Synoptic overview. Stroke. 2009;40:111–114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg M.D. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:363–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greensmith L. Mooney E.C. Waters H.J. Houlihan-Burne D.G. Lowrie M.B. Magnesium ions reduce motoneuron death following nerve injury or exposure to N-methyl-D-aspartate in the developing rat. Neuroscience. 1995;68:807–812. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00196-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl R. Schurer L. Schmid-Schonbein G.W. del Zoppo G.J. Experimental anti-leukocyte interventions in cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1108–1119. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatashita S. Hoff J.T. Salamat S.M. Ischemic brain edema and the osmotic gradient between blood and brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998;8:552–559. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi Y. Roussel S. Pinadr E. Seylaz J. Reduction of infarct volume by magnesium after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:1025–1030. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass I.S. Cottrell J.E. Chambers G. Magnesium and cobalt, not nimodipine, protect neurons against anoxic damages in the rat hippocampal slice. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:710–715. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H. Okuda S. Arachidonic acid as a neurotoxic and neurotrophic substance. Prog. Neurobiol. 1995;46:607–636. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00016-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita Y. Ueyama T. Senba E. Terada T. Nakai K. Itakura T. Expression of c-fos, heat shock protein 70, neurotrophins, and cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in response to focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats and their modification by magnesium sulfate. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:435–445. doi: 10.1089/089771501750171038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa H. Hayashi T. Mitsumoto Y. Koga N. Itoyama Y. Abe K. Reduction of ischemic brain injury by topical application of GDNF after permanent MCAO in rats. Stroke. 1998;29:1417–1422. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.7.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Omae T. Fisher M. Spontaneous hyperthermia and its mechanism in the intraluminal suture middle cerebral artery occlusion model of rats. Stroke. 1999;30:2464–2471. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.Y. Chung S.Y. Lin M.C. Cheng F.C. Effects of magnesium sulfate on energy metabolites and glutamate in the cortex during focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in the gerbil monitored by a dual-probe micro-dialysis technique. Life Sci. 2002;71:803–811. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.N. He Y.Y. Wu G. Khan M. Hsu C.Y. Effect of brain edema on infarct volume in a focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Stroke. 1993;24:117–121. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Chopp M. Jiang N. Zaloga C. In situ detection of DNA fragmentation after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Mol. Brain Res. 1995;28:164–168. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo E.H. A new penumbra: transitioning from injury into repair after stroke. Nat. Med. 2008;14:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nm1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa E.Z. Weinstein P.R. Carlson S. Cummings R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniotomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y. Anrather J. Kawano T. Niwa K. Zhou P. Ross E. Iadecola C. Prostanoids, not reactive oxygen species, mediate COX-2-dependent neurotoxicity. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:668–675. doi: 10.1002/ana.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinov M.B. Harbaugh K.S. Hoopes P.J. Pikus H.J. Harbaugh R.E. Neuroprotective effects of pre-ischemia intra-arterial magnesium sulfate in reversible focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosurg. 1996;85:117–124. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S.L. Manhas N. Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res. Rev. 2007;54:34–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni B.P. Zhu H. Knuckey N.W. Is magnesium neuroprotective following global and focal cerebral ischemia? A review of published studies. Magnes. Res. 2006;19:123–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen S. Fusco F.R. Yrjanheikki J. Keinanen R. Hirvonen T. Roivainen R. Närhi M. Hökfelt T. Koistinaho J. Spreading depression and focal brain ischemia induce cyclooxygenase-2 in cortical neurons through N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-receptors and phospholipase A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6500–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L. Polazzi E. Nicolini A. Cre'minon C. Levi G. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in cultured microglia by prostaglandin E2, cyclic AMP, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M. Kuwata H. Amakasu Y. Shimbara S. Nakatani Y. Atsumi G. Kudo I. Prostaglandin E2 amplifies cytosolic phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase-2-dependent delay prostaglandin E2 generation in mouse osteoblastic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19891–19897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainsford K.D. Current status of the therapeutic uses and actions of the preferential cyclo-oxygenase-2 NSAID, nimesulide. Inflammopharmacology. 2006;14:120–137. doi: 10.1007/s10787-006-1505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla A.K. Chawla M. Singh A. Nimesulide: some pharmaceutical and pharmacological aspects and update. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000;52:467–486. doi: 10.1211/0022357001774255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S. Yamashita T. Tanaka K. Hattori H. Sawamoto K. Okano H. Suzuki N. Activation of cytokine signaling through leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR)/gp130 attenuates ischemic brain injury in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:685–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R.A. Morton M.T. Tsao-Wu G. Savalos R.A. Davidson C. Sharp F.R. A semi-automated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:290–293. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takadera T. Ohyashiki T. Prostaglandin E2 deteriorates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated cytotoxicity possibly by activating EP2 receptors in cultured cortical neurons. Life Sci. 2006;78:1878–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takadera T. Yumoto H. Tozuka Y. Ohyashiki T. Prostaglandin E2 induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in rat cortical cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;317:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurnau G.R. Kemp D.B. Jarvis A. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of magnesium in patients with pre-eclampsia after treatment with intravenous magnesium sulfate: a preliminary report. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1987;157:1435–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai K.J. Tsai Y.C. Shen C.K. G-CSF rescues the memory impairment of animal models of Alzheimer's disease. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1273–1280. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai K.J. Yang C.H. Fang Y.H. Cho K.H. Chien W.L. Wang W.T. Wu T.W. Lin C.P. Fu W.M. Shen C.K. Elevated expression of TDP-43 in the forebrain of mice is sufficient to cause neurological and pathological phenotypes mimicking FTLD-U. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1661–1673. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakita H. Tomimoto H. Akiguchi I. Lin J.X. Miyamoto K. Oka N. A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor attenuates white matter damage in chronic cerebral ischemia. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1461–1465. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K. Andreasson K.I. Kaufmann W.E. Barnes C.A. Worley P.F. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron. 1993;11:371–386. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90192-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Chen T.Y. Kirsch J.R. Toung T.J.K. Traystman R.J. Koehler R.C. Hurn P.D. Bhardwaj A. Kappa-opioid receptor selectivity for ischemic neuroeprotection with BRL 52537 in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2003;97:1776–1783. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000087800.56290.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.