Abstract

The new direction in Maya archaeology is toward achieving a greater understanding of people and their roles and their relations in the past. To answer emerging humanistic questions about ancient people's lives Mayanists are increasingly making use of new and existing scientific methods from archaeology and other disciplines. Maya archaeology is bridging the divide between the humanities and sciences to answer questions about ancient people previously considered beyond the realm of archaeological knowledge.

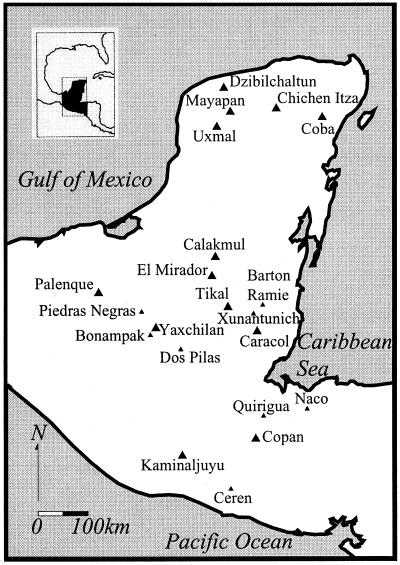

Questions about time, space, and people form the core of the social sciences. Given the material and spatial nature of the archaeological record, archaeologists have always been at the forefront of research on time and space. Over the past century Maya archaeologists have developed a deep understanding of the duration and spatial extent of occupation in the Maya area [which extends at least as far back as the Paleo-Indian period ca. 10,000 before Christ and includes what is now Guatemala, Belize, southern Mexico, western Honduras, and El Salvador; Fig. 1 (1–4)].† The new direction in Maya archaeology, and archaeology in general, is toward a greater understanding of people in the past (5). The fundamental, but inanimate, questions of what, when, and where, are being complemented by animate questions of how, why, by whom, and with what meaning.

Figure 1.

Map of the Maya area showing major sites and sites mentioned in the text.

This study of a peopled past brings to the interpretive foreground what we have always known: the disembodied materials that constitute the contemporary archaeological record are simply the remains of once active ancient landscapes. To answer humanistic questions about the lives of ancient people Maya archaeologists are increasingly making use of new and existing scientific methods to complement more conventional archaeological and art historical analyses. This multidisciplinary research bridges the divide between the humanities and sciences. It enables archaeologists to propose answers to questions previously considered beyond the realm of archaeological knowledge—questions about people's life cycles and life histories, and their perceptions of the world. Another significant breakthrough in the ability of archaeologists to understand ancient Maya people has been the decipherment of the Classic (anno Domini 250–900) Maya hieroglyphic writing system. Classic Maya rulers recorded versions of their life histories in hieroglyphic texts and images inscribed throughout their cities. These public narratives combined history, worldview, and personal and political goals, strategies, and agendas. They provide personalized glimpses into the lives of rulers and other elites.‡

Finding Out About the People

An example of the new multidisciplinary work in Maya archaeology comes from the Early Copán Acropolis Project, directed by Robert Sharer. Excavations in the civic-ceremonial heart of this ancient city in Honduras located the tomb of a male considered to be the dynastic founder, Yax K'uk' Mo'. Throughout world history—and Copán is no exception here—kings have sought to legitimate their power by claiming to have arrived from a distant realm. In one of his inscriptions, Copán's founder seems to make such a claim. Archaeologists and historians often have been baffled to determine the truth behind such statements. Did the king really come from afar? Or was he just using that claim to legitimate his power? How would we know if all we have access to, beyond the claim, is the buried remains of the king's body? Jane Buikstra's innovative application of strontium isotope ratio analysis on Yax K'uk' Mo's remains determined both that Yax K'uk' Mo' had arrived at Copán in late adulthood and had likely come from the Petén area of Guatemala, where the major Maya city of Tikal is located (7). Corroborating evidence for Yax K'uk' Mo's extensive network of long-distance communications comes from Ellen Bell, Dorie Reents-Budet, and Ron Bishop's neutron activation analysis of the ceramic offerings from his tomb (8). The tomb contained locally manufactured vessels, as well as those manufactured in various other locales in the Maya area and in highland Mexico, near the city of Teotihuacan. Stylistically, the vessels in Yax K'uk' Mo's tomb resemble those of royal tombs from the Maya cities of Tikal and Kaminaljuyu. To date, the study of epigraphy, bone chemistry, and ceramic chemistry at Copán combine to provide an unusual glimpse into Yax K'uk' Mo's personal origins and suggest close, and likely face-to-face, interaction among ancient Maya elites.

The analysis of burials, from social and bioarchaeological perspectives, has always been a critical means for archaeologists to assess past people—rich and poor. Maya burial studies are particularly illuminating because the ancient Maya typically buried people in the floors of their houses, rather than in cemeteries. Like archaeologists studying cemeteries, Mayanists have analyzed burials to examine how personhood (self, gender, sexuality, age, beauty) intersect with socio-economic (status, diet, health), political, and religious dimensions of life. But because people were buried in the floors of their houses, Mayanists also can use burial analyses to reconstruct family grouping and from these infer kin organization and relationships (9, 10). Even from some of the humblest households, Patricia McAnany has discerned from distinctive patterning in the form and location of interments how ordinary people revered the important personages (ancestors) from their kin group (11).

Even more intimate details of people's lives are now being gleaned through new applications of existing bioarchaeological techniques. Lori Wright and Francisco Chew have used collagen analysis in infant bones and stable oxygen isotope ratios of adult tooth enamel to determine how long women living in the Dos Pilas region of Guatemala breast fed their children (12). The up to 4 years of ancient mothers' breast feeding is more than twice as long as contemporary breast feeding. Intriguingly, the Classic period adults of this area survived childhood anemia to a much greater extent than contemporary people survive this disease. This leads Wright and Chew to the seemingly counterintuitive conclusion that ancient Maya children were living under healthier conditions than modern Maya children, and that this enhanced health is related in part to the benefits of extended breast feeding.

Knowledge about the past is not merely esoterica about some place and some people that no longer exist. In research such as the aforementioned, there are many “lessons from the past” that can provide useful information for today's world (13).

Some of the most extensive discussions of the intimate aspects of ancient people's lives are based on advances in archaeological and art historical analyses of images of people—images molded as figurines, painted on ceramics, or inscribed on monuments. Iconographic (refs. 14–17; Fig. 2) and textual (18) research is pushing these analyses forward to answer questions about ancient people's perceptions of self, beauty, status, and sexuality. From the oft opposing corners of humanism and science, research interests are intersecting to reveal personal details about ancient people once deemed beyond the reach of archaeology.

Figure 2.

Human face from a residential area in La Sierra, the Late Classic (anno Domini 600–800) capital of the Naco Valley, Honduras. Ear ornaments and head band may indicate this person's elite status. Photograph by Ellen Bell.

Exacavating Where People Really Lived: Household, Community, and Settlement Studies

Peopling the past is not just about finding ancient people. In many archaeological contexts it is impossible to locate actual people (in human remains, images, or texts). Peopling the past is about understanding the interconnections between people and other aspects of social life. Whether or not we can find people in the archaeological record, we can infer their presence, roles, and relations. In Maya studies, as in archaeological research around the world, the development of household, community, and settlement archaeology has been a springboard for analyses of a peopled past. It has now been many decades since Maya archaeology deserved its old stereotype of being “the archaeology of temples and tombs.” From the 1960s onward the pioneering work of Gordon Willey and Wendy Ashmore, among many others, has inspired new generations of archaeological research into the places where people really lived: households, communities, and settlements (19–21). To illustrate this research I discuss below two household archaeology case studies, one from the Cerén Project directed by Payson Sheets (22, 23), and the other from the Xunantunich Archaeological Project, directed by Richard Leventhal and Wendy Ashmore (24–28).

The rural village of Cerén in El Salvador is the Pompeii of the New World. Around anno Domini 600 the Loma Caldera volcano erupted, burying Cerén below 5 meters of ash. Because the eruption was sudden, Cerén's inhabitants could only run from the village and had to leave their possessions behind. Given its abandonment and the preservative properties of volcanic ash, Cerén provides Maya archaeologists§ an unprecedented opportunity to examine the daily life of commoners at a precise moment in time. Researchers are drawing on archaeological, geophysical, volcanological, and paleoethnobotanical techniques to answer questions about Cerén (22).

Even the footprints in the gardens, the foot traffic marks through the yards, and the finger swipes across food left in dishes were found. The Loma Caldera eruption seems to have happened in August because the corn plants in fields had matured and the first corn harvest was underway. It is also likely that it happened early in the night, after dinner because the dishes were still dirty, but the sleeping mats were rolled up.

People at Cerén seem to have taken care to “child-proof” their houses as they had secured their sharp cutting items and valuables in hard to reach places, such as in the roofing thatch or on top of walls (23). Cerén's inhabitants were farmers and cotton cloth producers. Because perishables were preserved at Cerén we even know the types of wood people used in construction and the range of food they planted, ate, and presumably traded or provided as tribute (42). Interestingly, the residents of Cerén's humble households had sufficient housing, a good food supply, and an elaborate aesthetic sense (which included objects of their own manufacture as well as highly regarded objects acquired from elsewhere). Indeed the quality of life for ancient Cerén inhabitants was much better than that of contemporary rural El Salvadoraneos. But Sheets (22) cautions us not to see Cerén as a “Garden of Eden.” Cerén's inhabitants were not economically self-sufficient. Many of their daily essentials came from elsewhere and their local resources were hardly equal to those of the higher status people with whom they interacted.

Given the poor preservation in the tropics, we usually can't assess the richness of people's everyday lives the way we can at Cerén. But Mayanists are turning to more extensive excavations of households, and even whole neighborhoods and communities, to collect more comprehensive information on people's everyday lives. Even at Cerén, the excavation of a house in isolation or the excavation of a test pit (a small, often no larger than 2 m by 2 m, excavation resembling a telephone booth) into a house, would not provide sufficient evidence for documenting everyday life. We conducted extensive excavations of rural settlements throughout the Xunantunich polity in Belize, in conjunction with excavations within the city of Xunantunich itself.

Chan Nòohol is one of many small agrarian settlements that comprise the Xunantunich polity's dispersed hinterlands (24–26). Through terracing and fertilization—the latter evidenced through soil chemical analysis—Chan Nòohol's farmers converted the sloping land around them into a productive agricultural landscape that supported over a century of habitation and presumably surpluses. The agricultural enhancement of Chan Nòohol's farmsteads is quite compatible with the soil chemical evidence that Nicholas Dunning (29) has procured from elsewhere in the Maya region. Archaeological, soil chemical, and paleoethnobotanical studies of Chan Nòohol's outdoor spaces allowed me to define the activity areas and pathways which provided the basis for reconstructing how Chan Nòohol's farmers constructed, used, and moved around their farmsteads and community as part of daily and seasonal work routines.

Chan Nòohol's short-term occupation in the Late Classic (anno Domini 660–780), is parallel to that of many other small agrarian settlements in the Xunantunich hinterlands, and perhaps unsurprisingly, concurrent with Xunantunich's rise to regional political power and its largest construction boom. Direct and indirect interactions between polity elites and people living in hinterland settlements suggests an interrelationship between local settlements and the regional political system, in which each simultaneously impacts and is impacted by the other.

Xunantunich's hinterlands were far from homogeneous as Jason Yaeger's work at San Lorenzo attests (25–28). Although San Lorenzo is located only 4 km from Chan Nòohol, its historical trajectory, resource base, productive economy, and socio-political relations with the polity elites were quite different. San Lorenzo was a more socio-economically heterogeneous and longer lived settlement than Chan Nòohol. Its populace farmed alluvial flood plains and had access to chert deposits (the material used to make stone tools). Some people at San Lorenzo displayed their links to Xunantunich elites by using and wearing exotic objects. Increasing archaeological evidence such as these studies clearly illustrate that Maya commoners were far from an isolated homogeneous peasantry. Maya commoners were a diverse and innovative group, who actively and variably partook in their society.

Although these two case studies pertain to Maya commoners, household archaeology is not synonymous with the study of commoners. Household archaeology did open the door for the study of commoners through the remains of their houses, where archaeology had previously assessed only elites through the remains of temples in cities. But household archaeology entails the study of the houses of all people, and Mayanists are equally assessing details of elite lives through household studies (30–33). Commoners as well as elites lived in cities and rural areas. Residential patterns in cities and their hinterlands were complex, as Anne Pyburn's findings of economically distinct neighborhoods indicates (34).

The Social Differences That Distinguished Them: Gender, Status, and Identity

“The Maya” is our term for a diverse group of people. Three critical lines of diversity that are currently receiving attention are gender, status, and identity.

Rosemary Joyce has compared depictions of women and men on different mediums—royal art, elite polychrome vessels, and figurines from a range of households—to assess how gender roles and identities varied across status lines (14). Imagery from elite and commoner household contexts portrays men as warriors, ritual hunters, and musicians and women as weavers and food preparers. In royal imagery men are portrayed in a complimentary manner, whereas women are shown in ritual, not productive, roles. Whereas male roles were portrayed consistently across status lines, female roles were portrayed differently across status lines (although the ceramic bowls and cloth bundles that women hold in royal images may reference their production of these items). Joyce suggests that the absence of images of women's labor in royal art may represent the royalty's interests in de-emphasizing the potential economic importance of household production.

In royal images there were often correlations between gender roles (or relations) and their spatial location on a monument or within a city (15, 35). By contrast, in elite (32) and commoner (24) households space was not exclusively partitioned into male and female areas, suggesting distinctions between the gendering of political ideologies and of domestic life, as Julia Hendon (32) argues. Variability in gender relations likely will continue to emerge as new research expands in this area. But an underlying principle of gender complementarity seems pervasive in the ancient Maya past. Gender complementarity implies that the female-male pair is the significant unit in society and that this unit is constructed through the union of different actions undertaken by differently gendered persons.

Schortman and Urban's work (36) on Maya to non-Maya interaction provides a similar critique of static models of social interaction, but in their case the interaction is between distinct identity groups. It is often assumed that the more complex group (the Maya) in a sphere of interaction will dominate the less complex group (the non-Maya). In terms of non-Maya peoples living in the Naco Valley of Honduras who were interacting with Maya peoples from the polities of Copán and Quirigua, neither group was able to dominate resources, production, transportation, and military processes and therefore predetermine a network of dependency between the two groups.

Recent research on gender, status, and identity is reconfiguring our understanding of organization and power relations in Maya society. Historically, social scientists have deemed the powerful actors of history to be elites, male elites, or Western male elites. New research on “other” groups—groups considered to be marginal in contemporary western society—now shows that these other groups play active and integral roles within their society. Although some groups may have less power than others, this does not mean that they were powerless.

The Beliefs That Bound Them

Despite their differences there seem to be certain core beliefs about the world that ancient Maya people held in common. The archaeology of belief is as new as the archaeology of people. It has often been considered even more impossible to assess the thoughts of ancient people than to assess the now deceased people themselves. But, as Wendy Ashmore (37) has shown, ancient people arranged their buildings in meaningful ways throughout Maya cities and a cultural map of their worldview can be inferred from a city's plan. For the ancient (and modern) Maya the cardinal directions were a key organizational principle for their world. Kings often constructed royal residences in northern locations within cities plausibly to represent their power as a zenith of power (in Maya cosmology north is associated with the sun's ascension to zenith, the northern position in the sky). Within individual images people were systematically depicted in certain locations to represent powerful positions and balances of power between different groups—gender groups, kin groups, and political factions (15, 35). At the regional scale similar principles of directionality were invoked for the positioning of cities. This past year Gair Tourtellot and colleagues (38) predicted and located the position of four minor cities situated equidistant and in cardinal orientations from the city of La Milpa in Belize.

Representations of the cardinal world axes often depict a cave at the center of these axes. Indeed James Brady and colleagues (39, 40) have shown that many Maya cities were constructed on top of caves. But even more intriguing they have found cases where caves do not occur naturally, but the Maya dug an artificial cave below their city.

Does this worldview represent an elite worldview or a variant of the perspectives of all Maya people? At Chan Nòohol, the farmers of one farmstead deposited a cache of ordinary river cobbles on top of a small chultun [an underground storage chamber with a cave-like shape (24)]. I interpreted the cobbles as a cache because their arrangement and coloration are reminiscent of modern and ancient Maya quadripartite directional cosmograms, where each cardinal direction and the center corresponds to a color with green in the center, white to the north, yellow to the south, red to the east, and black to the west. Other recent excavations have uncovered caches of mundane objects deposited in a quadripartite pattern in a number of commoner households throughout the Maya area (11).¶ It appears that Maya commoners, as well as elites, reckoned a world represented by the cardinal directions and a center.

Identifying commoner rituals is a more recent development than the identification of elite rituals. Because the items commoners use in rituals are often ordinary objects, their ritual significance could be overlooked. As Lisa Lucero and William Walker (41) have shown in their reanalysis of a house construction sequence from Barton Ramie, Belize, archaeologists can recognize the myriad of pathways through which the familiar can be imbued with ritual practices. If the ritual practices archaeologists initially recognized as Classic Maya elite rituals were indeed preformed ubiquitously throughout commoner households in the Classic and earlier periods, then it just may be that many Classic period elite rituals were derived from the domestic ritual practices of ordinary Maya people (11, 41).

Conclusion

Jeremy Sabloff, the director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, opened his book on the Maya with the shocking statement, “I am not particularly interested in ancient objects” (1). Of course we are interested in ancient objects because these are the material record that we study. But the new direction in archaeology is to use the interpretation of inanimate objects to understand the animate societies from which the objects derived. The old view that portrayed the ancient Maya landscape as a relatively unpopulated expanse of empty ceremonial centers where a few priests guided the lives of a few peasants is certainly giving way to a picture of an active and vibrant Maya world, with a socially and economically distinctive cast of characters who all had something to offer their society and us.

Acknowledgments

I thank Jeremy Sabloff, Ellen Bell, Payson Sheets, Bill Middleton, Dorie Reents-Budet, Jason Yaeger, Lisa Lucero, David Lentz, and Edward Robin for their helpful comments on this review. Robert Sharer and Ellen Bell were generous in providing access to original artifact photographs. I thank Mark Schwartz for creating Fig. 1. Bridget Coughlin's advice greatly simplified the process of manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

I refer readers to the aforementioned reviews for more extensive bibliographies than space permits here.

A review of recent research in Maya epigraphy would require a separate article. For an overview of recent research see ref. 6. Herein I will reference epigraphic research as it is part of multidisciplinary research programs.

We do not know whether Cerén's inhabitants were ethnically Maya or Lenca.

Garber, J. & Brown, M. K., 61st Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, April 11, 1996, New Orleans, LA.

References

- 1.Sabloff J A. The New Archaeology and the Ancient Maya. New York: Scientific American Library; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fash W L. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1994;23:181–203. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus J. J Archaeol Res. 1995;3:3–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucero L J. J World Prehistory. 1999;13:211–263. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brumfiel E M. Am Anthropol. 1992;94:551–567. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schele L, Freidel D A. A Forest of Kings. New York: Morrow; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buikstra J. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan. Bell E E, Canuto M A, Sharer R J, editors. Los Angeles: Cotsen Press; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell E E, Reents-Budet D. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan. Bell E E, Canuto M A, Sharer R J, editors. Los Angeles: Cotsen Press; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haviland W A. In: Household and Community in the Mesoamerican Past. Wilk R R, Ashmore W, editors. Albuquerque: New Mexico Univ. Press; 1988. pp. 121–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robin C. Preclassic Maya Burials at Cuello, Belize. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports International Series; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAnany P A. Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya Society. Austin: Texas Univ. Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright L E, Chew F. Am Anthropol. 1999;100:924–939. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice D S, Rice P M. Latin Am Res Rev. 1984;19:7–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce R A. Curr Anthropol. 1993;34:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyce R A. In: Gender in Archaeology: Essays in Research and Practice. Wright R P, editor. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Univ. Press; 1996. pp. 167–198. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joyce R A. In: Recovering Gender in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. Klein C, editor. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell, E. (1991) B.A. honors thesis (Kenyon College, Gambier, OH).

- 18.Houston S, Stuart D. Res Anthropol Aesthetics. 1998;33:73–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashmore W, editor. Lowland Maya Settlement Patterns. Albuquerque: New Mexico Univ. Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilk R R, Ashmore W, editors. Household and Community in the Mesoamerican Past. Albuquerque: New Mexico Univ. Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster D, Gonlin N. J Field Archaeol. 1988;15:169–190. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheets P. The Cerén Site. Brace, Jovanovitch, New York: Harcourt; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheets P. Revista Española Anthropol Am. 1998;28:63–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robin C. Ph.D. thesis. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashmore W, Yaeger J, Robin C. In: The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation. Rice D, Rice P, Demarest A, editors. Boulder: Westview; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaeger J, Robin C. In: Ancient Maya Commoners. Valdez F, Lohse J, editors. Austin: Texas Univ. Press; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaeger J. Ph.D. thesis. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaeger J. In: The Archaeology of Communities: A New World Perspective. Yaeger J, Canuto M, editors. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smyth M P, Dore C D, Dunning N P. J Field Archaeol. 1995;22:321–347. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chase D Z, Chase A F, editors. Mesoamerican Elites: An Archaeological Assessment. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendon J A. Am Anthropol. 1991;93:894–918. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendon J A. In: Women in Prehistory: North America and Mesoamerica. Claassen C, Joyce R A, editors. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Univ. Press; 1997. pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeCount L J. Latin Am Antiquity. 1999;10:239–258. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyburn K A. In: The Archaeology of City States: Cross Cultural Approaches. Charleton T, Nichols D, editors. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1997. pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robin C. In: New Directions in Kinship Studies. Stone L, editor. Boulder: Rowman and Littlefield Press; 2001. pp. 204–228. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schortman E M, Urban P A. Curr Anthropol. 1994;35:401–430. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashmore W. Latin Am Antiquity. 1991;2:199–226. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tourtellot G, Wolf M, Estrada Belli F, Hammond N. Antiquity. 2000;74:481–482. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brady J E, Ashmore W. In: Ideational Landscapes: Conceived and Constructed. Ashmore W, Knapp A B, editors. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999. pp. 124–148. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brady J E, Veni G. Geoarchaeology. 1992;7:149–167. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker W H, Lucero L J. In: Agency in Archaeology. Dobres M-A, Robb J E, editors. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lentz D L, Beaudry-Corbett M P, Reyna de Aguilar M L, Kaplan L. Latin Am Antiquity. 1996;7:247–262. [Google Scholar]