Summary

The mechanisms by which epithelial cells distinguish pathogens from commensal microbes have long puzzled us. Now, McEwan et al. and Dunbar et al. demonstrate that in C. elegans, microbial toxin-induced inhibition of host cellular functions, especially blockade of protein translation, activates the effector-triggered immune response dependent on the transcription factor ZIP-2.

During the last two decades fundamental mechanisms of pathogen sensing have been under intense investigation and debate, mainly focusing on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and the pathogen or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs) that they recognize. According to this paradigm, a broad range of microbial molecules that share common structural motifs, such as the bacterial peptidoglycan or fungal cell wall components, are recognized by evolutionarily conserved receptor proteins on antigen presenting cells (APCs) and other inflammatory cells. Probably the best-known examples of these PRRs are the mammalian Toll-like receptors, which recognize a plethora of microbial components and trigger multiple defense response pathways, including NF-κB, IRF, and MAPK signaling pathways. Once activated through their PRR(s), these cells in turn signal the presence of an infection and can further activate the adaptive immune system (Medzhitov, 2009). This model, however, has some serious caveats. First, MAMPs are universal to all microbes, and therefore the model fails to distinguish a dangerous pathogen from a harmless commensal microbe. The danger model partially by-passed this problem suggesting that in addition to MAMPs, APCs can be activated by alarm signals (Danger-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs, or alarmins) released by nearby injured cells (Matzinger, 2002; Vance et al., 2009). Second, viruses are essentially made from the same building blocks as the host cell, and are still being recognized. And third, many organisms such as plants and nematodes lack professional circulating immune cells and adaptive immune responses. In addition, nematodes lack NF-κB, and their single Toll-like receptor homolog has only been indicated to play a role in immune signaling against Salmonella (Tenor and Aballay, 2008). Still, nematodes are perfectly capable of eliciting defense responses to various pathogens. Therefore, it has been proposed that instead of the MAMPs or PAMPs, immune signaling may be triggered in the nematode in response to the pathogen-induced damage or disruption in the cellular homeostasis. One particular example of this type of response is effector-triggered immunity (ETI), which is well demonstrated in plants. In this system, the host immune response is triggered by recognition of the effector molecules (i.e. virulence factors that microbes deliver into the host cells) or their effects on the host cellular homeostasis/function (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Göhre and Robatzek, 2008).

Two articles in this issue of Cell Host & Microbe, and a related publication in Cell, now elucidate previously uncharacterized mechanisms of ETI in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (McEwan et al., 2012; Dunbar et al., 2012; Melo and Ruvkun, 2012). C. elegans feeds on bacteria and a non-pathogenic E. coli is usually used as a food source in laboratory. However, ingestion of virulent bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14, can lead to a lethal intestinal infection. Virulence of PA14 is partially due to Exotoxin A (ToxA), which, like diphtheria and shiga toxins, is known to inhibit protein translation by altering a post-translational modification in elongation factor 2 (EEF2). In C. elegans, defense responses to P. aeruginosa are mediated by a bZIP transcription factor ZIP-2. This leads to transcription of target genes, including infection response gene-1 (irg-1) (Estes et al., 2010). To study if a xenobiotic molecule, such as ToxA, is sufficient to activate C. elegans immune responses, McEwan and colleagues fed the worms with a normally non-pathogenic E. coli engineered to express ToxA. They found that ToxA alone induced a subset of the genes normally upregulated following P. aeruginosa infection, indicating an ETI induced by the ribosomal inhibitor ToxA. This ToxA induced transcriptional program required the ZIP-2 transcription factor.

Since ToxA is a known inhibitor of protein translation, McEwan et al. also tested other translation inhibitors to determine if the translational block was sufficient to trigger these defense response pathways. Indeed, both hygromycin B and G418 induced irg-1 together with a subset of other immune response genes. Worms with mutated EEF2 (lacking the site for ToxA activity), or worms fed with catalytically inactive ToxA showed no irg-1 transcription, emphasizing the role of translational block in triggering defense responses.

The accompanying paper by Dunbar et al. confirms these findings and reveals the mechanism by which the defense-triggered ZIP-2 expression is activated despite the ToxA-mediated blockade of translation. Initially, they screened for RNAi targets that induced irg-1 expression in the absence of an infection or other stressors, and identified several core host pathways, especially translation machinery components. Next, translation elongation was blocked with cycloheximide and was also found to result in ZIP-2-dependent induction of irg-1 expression. Furthermore, they demonstrated in agreement with McEwans et al. that P. aeruginosa infection blocks protein production in the host intestine and this is due to ToxA that enters the cells by endocytosis. To reveal the mechanism by which inhibiting translation activates irg-1 transcription, Dunbar et al. further investigated the dynamics and regulation of zip-2 expression. zip-2 mRNA levels were found to be similarly high in both uninfected and infected animals. However, a zip-2–GFP protein fusion reporter showed dramatically different results. While GFP was barely detected in conventionally reared reporter animals, P. aeruginosa induced robust zip-2-GFP expression and nuclear localization in intestinal cells. Cycloheximide treatment mimicked the effects of P. aeruginosa infection, further supporting the notion that a blockade of translation initiation triggers the production of ZIP-2 protein. Finally, Dunbar et al. suggest that an upstream open reading frame (uORF) in 5’ UTR of zip-2 plays a key role in overriding the pathogen-induced block in translation, which in turn leads to increased levels of ZIP-2 transcription factor, and induction of transcription of irg-1 and other defense response genes.

Another recent paper from Melo and Ruvkun (2012) extends the notion of defense responses triggered by damaging key cellular machinery beyond the translation apparatus. In this study, an RNAi screen was engineered to identify genes involved in regulating the behavioral response to microbial food sources. Through this screen, they discovered that disruption of many core cellular functions, such as protein translation, mitochondrial respiration, proteasome activity, or actin cytoskeleton and microtubule dynamics, results in activation of detoxification and immune responsive gene expression programs (including ZIP-2-dependent irg-1 expression), in addition to behavioral changes.

While ETI is a well-characterized immune sensing mechanism in plants (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Göhre and Robatzek, 2008), similar phenomenona in animal systems have only recently been reported. For example, Boyer et al. (2011) studied a toxin, CNF1, from uropathogenic E. coli that catalyzes deamidation and activation of Rac2. In the Drosophila system, they found that the activated Rac2 binds the adaptor protein IMD, a core component of one of the major NF-κB immune signaling pathways in flies, and triggers immune responses independent of PRR-mediated recognition. Similar findings were also reported with activated Rac2 interacting with RIP1 or RIP2 and triggering NF-κB responses in mammalian cells. Now, this current batch of papers from the C. elegans systems suggests that disruption of many cellular processes are also likely to trigger immune defense transcriptional responses.

Indirect sensing of pathogens and ETI clearly offer significant advantages for the host. Monitoring of only few core pathways and cellular activities instead of (or in addition to) evolving specific PRRs for multiple unknown toxins or environmental threats creates a more versatile and adaptable infection/stress sensing system. Since many pathogens are known to avoid detection by modifying PAMPs or subverting PRR signaling (Roy and Mocarski, 2007), the ETI response offers the host added protection from these virulent microbes. Also, the activation of ETI defense response pathways is likely faster than if the response would depend solely upon danger signals (DAMPs) released from dead cells. In addition, of course, non-biologic xenobiotic threats can be sensed and defended against through these pathways. Regardless, these recent advances open new avenues for further investigation into the links between cellular damage, caused by either chemical or biological agents, and stress or immune defense-associated transcriptional responses.

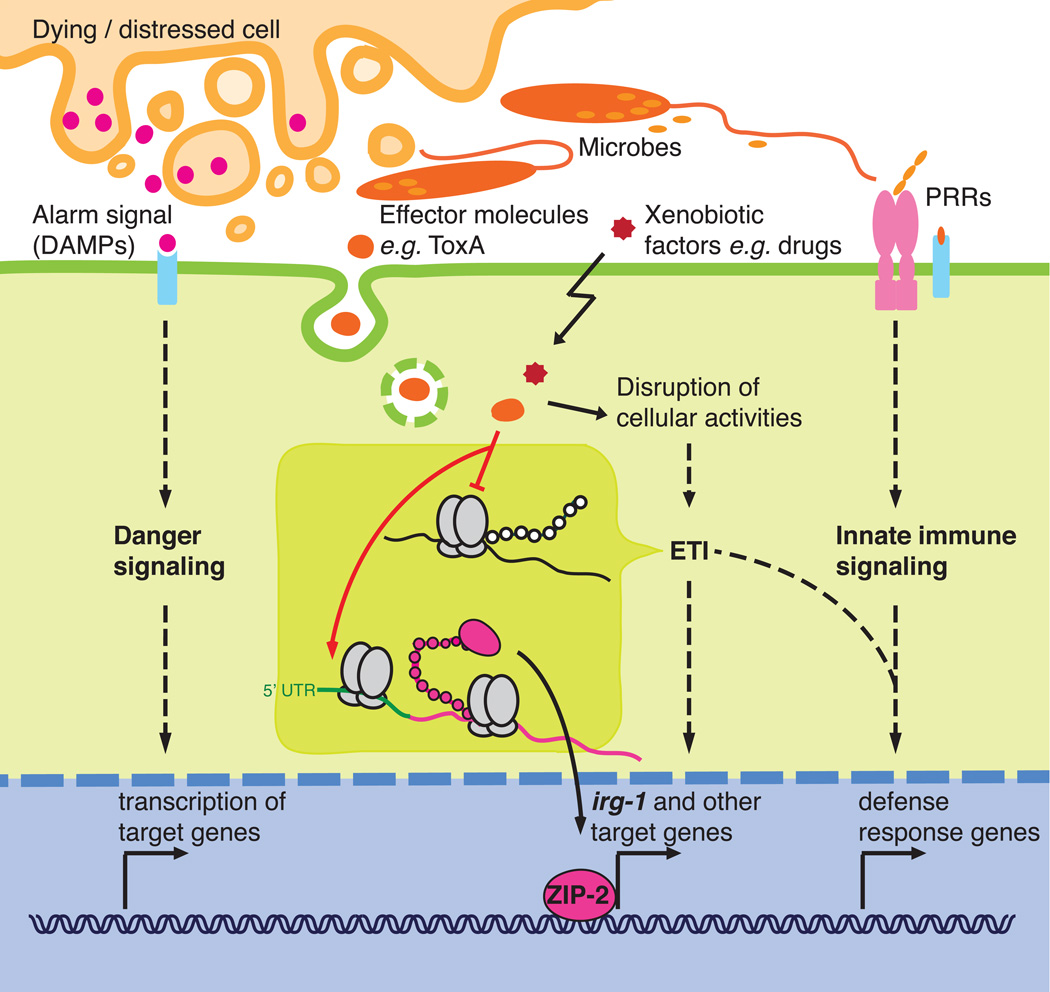

Figure 1. Model for activation of metazoan innate immune responses.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) bind microbial components and trigger signaling cascades, which lead to the transcription of potent antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, and other defense response genes. To discriminate harmless commensal microbes from pathogens and to indirectly sense the presence of pathogenic effector molecules (toxins/virulence factors) that PRRs fail to recognize, cells monitor alarm signals from distressed or dying neighboring cells (Danger model) and/or the integrity of essential cellular functions in the effector-triggered immunity model (ETI). For example, inhibition of translation by bacterial toxins or drugs activates translation of the ZIP-2 message and the induction of the irg-1 response in C. elegans.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Boyer L, Magoc L, Dejardin S, Cappillino M, Paquette N, Hinault C, Charriere GM, Ip WE, Fracchia S, Hennessy E, et al. Identification of a conserved mechanism of effector-triggered immunity mediated by IMD and Rip proteins. Immunity. 2011;35:536–549. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar TL, Yan Z, Balla KM, Troemel ER. C. elegans detects pathogen-induced translational inhibition to activate bZIP immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.008. IN PRESS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes KA, Dunbar TL, Powell JR, Ausubel FM, Troemel ER. bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:2153–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914643107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre V, Robatzek S. Breaking the barriers: microbial effector molecules subvert plant immunity. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2008;46:189–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.46.120407.110050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. The danger model: A renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan DL, Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A triggers an immune response in Caenorhabditis elegans through translational inhibition. Cell Host Microbe. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.007. IN PRESS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Approaching the asymptote: 20 years later. Immunity. 2009;30:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of conserved genes induces microbial aversion, drug detoxification, and innate immunity in C. elegans. Cell. 2012 IN PRESS. [Google Scholar]

- Roy CR, Mocarski ES. Pathogen subversion of cell-intrinsic innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1179–1187. doi: 10.1038/ni1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenor JL, Aballay A. A conserved Toll-like receptor is required for Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:103–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Isberg RR, Portnoy DA. Patterns of pathogenesis: Discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]