Summary

It is well known that oocytes can reprogram differentiated cells, allowing animal cloning by nuclear transfer. We have recently shown that fertilized zygotes retain reprogramming activities [1], suggesting such activities might also persist in cleavage stage embryos. We have used chromosome transplantation techniques to investigate whether the blastomeres of two-cell stage mouse embryos can reprogram more differentiated cells. When chromosomes from one of the two blastomeres were replaced with the chromosomes of an embryonic or CD4+ T-lymphocyte donor cell, we observed nuclear reprogramming and efficient contribution of the manipulated cell to the developing blastocyst. Embryos produced by this method could be used to derive stem cell lines and also developed to term, generating mosaic “cloned” animals. These results demonstrate that blastomeres retain reprogramming activities and support the notion that discarded human preimplantation embryos may be useful recipients for the production of genetically tailored human embryonic stem cell lines.

Keywords: blastomere, mitosis, chromosome condensation, stem cell, reprogramming, development

Results and Discussion

Reprogramming by nuclear transfer allows the generation of animals and embryonic stem cell lines from somatic cells [2]. This approach, if successful with human cells, would allow the production of human stem cell lines from individual patients for personalized medicine or in vitro modeling of their condition [3–5]. However, attempts to produce human embryonic stem cell lines by nuclear transfer have thus far been unsuccessful, in part due to the limited availability of human oocytes.

Reprogramming by nuclear transfer is only successful under certain specific conditions, making it difficult to source the appropriate recipient cell-types. Reprogramming and embryonic development can occur in animals after transfer of somatic nuclei into oocytes and zygotes in metaphase of the cell cycle, but fails after transfer during interphase [6–8]. Nuclear transfer into embryonic blastomeres enucleated in interphase has also been attempted, but failed to demonstrated reprogramming activities [9, 10]. In particular, no development was observed after transfer of inner cell mass nuclei into 2-cell stage embryos enucleated in interphase [10].

Our results suggest that one key to successful reprogramming is the removal of the recipient cell genome at metaphase when the nuclear envelope is broken down and chromosomes are condensed (Fig. 1a). This suggests that reprogramming might also be possible in cell types other than oocytes or zygotes, if and only if their genome is removed in mitosis. Because they are relatively large embryonic cells, we first considered whether the blastomeres in a two-cell mouse embryo harbored reprogramming activities.

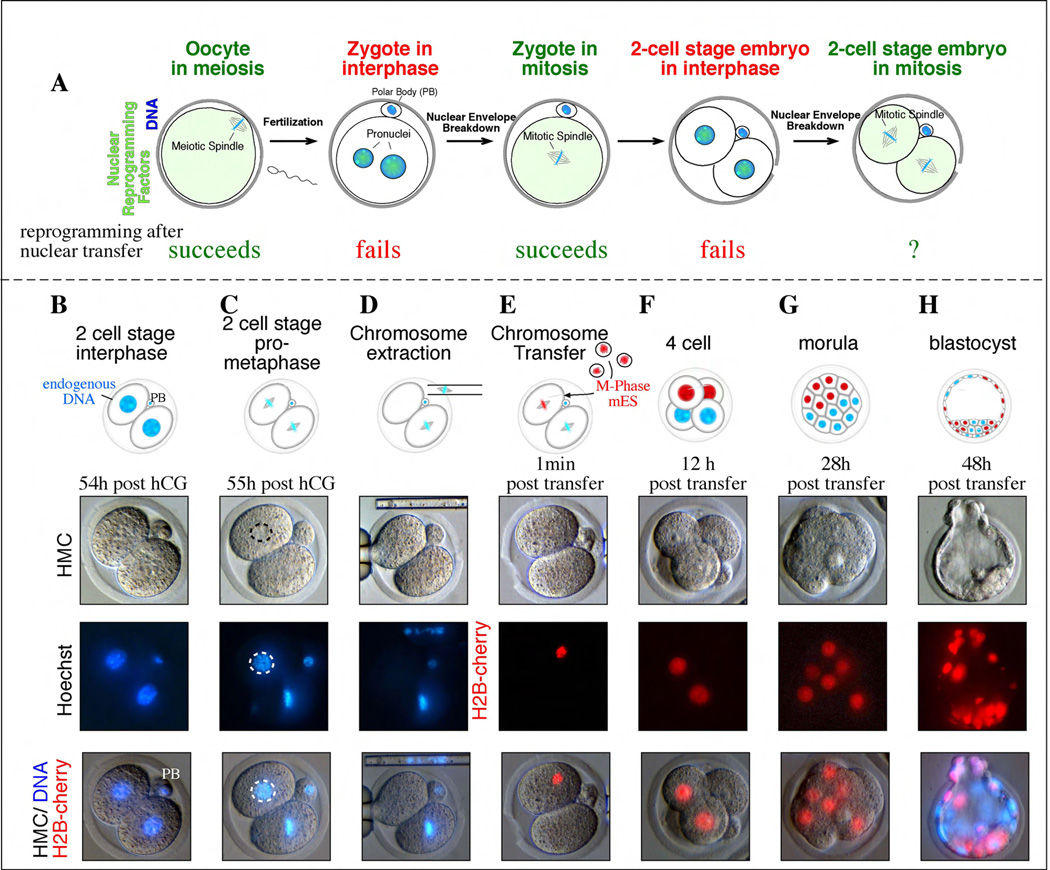

Figure 1. Chromosome transfer into mitotic blastomeres.

a, Stages of development from the unfertilized oocytes to the 2-cell stage embryo. Oocytes in meiosis and zygotes in mitosis are suitable for nuclear transfer, but not zygotes in interphase or even 2-cell stage embryos in interphase. Whether 2-cell stage embryos in mitosis can be used for transfer of a genome from a more differentiated cell is addressed here. b, 2-cell stage embryo in interphase 54h post hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone stimulating ovulation). c, Blastomeres in mitosis 55h post hCG. d, One blastomere had the genome removed in mitosis. e, One of the two blastomeres transferred with mouse ES cells expressing H2B-cherry. f, A 4-cell stage embryo 12h post transfer. g, Morula at 28h post transfer, composed of 8 cells, 4 of which are derived from the transferred blastomere. H) Blastocyst at 48h post transfer. PB= polar body.

To determine whether blastomeres contained reprogramming activities, we sought to stably but reversibly arrest them in mitosis for chromosome transfer studies. We isolated fertilized zygotes from superovulated mice and cultured them in vitro to the two-cell stage and then observed the embryos for entry into the second mitosis. The two blastomeres usually entered mitosis between 48 and 54 hours after administration of the hormone trigger for ovulation. Shortly after mitotic entry, the embryos divided to the 4-cell stage. To find the optimal conditions in which two-cell embryos could be arrested in mitosis, we cultured them in the presence of several nocodazole concentrations (Supplemental Table 1). Mouse 2-cell embryos required similar or slightly higher nocodazole concentrations for mitotic arrest then had zygotes [11]. To determine whether cell-cycle arrest was compatible with embryo viability, we released embryos from the mitotic block and allowed these embryos to develop in vitro to the blastocyst stage. We found that 32/35 embryos reached the blastocyst stage (91%), indicating that mitotic arrest with nocodazole did not significantly compromise later development. This finding was consistent with previous studies, which also suggested that a transient arrest in mitosis by nocodazole was non-toxic to the embryo [12].

When two-cell embryos were treated with 0.1µg/ml of nocodazole, we observed that they formed an irregular and unstable spindle that was presumably too disorganized to allow mitotic progression (Supplemental Fig. 1). Although the spindle was disorganized enough to cause mitotic arrest, it was still visible under Hoffman modulation contrast optics (Fig. 1c). When these two-cell embryos were further treated with cytochalasin B, to depolymerize the actin cytoskeleton, the spindle complex with attached chromosomes could still be indentified and removed by micromanipulation (Fig. 1D). In all cases, when the spindle was extracted from one of the two blastomeres, staining with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 demonstrated that the chromosomes were also successfully removed. We initially removed the chromosomes from only one of the two blastomeres and left the other blastomere intact because it would allow a direct comparison of developmental potential of the transferred with the non-transferred blastomere.

To optimize chromosome transfer into blastomeres and to determine whether they contained reprogramming activities, we arrested mouse ES cells in mitosis with nocodazole and injected their chromosomes into the enucleated blastomere (Fig. 1e, Supplemental Movie). To allow fate-mapping of the blastomere that had undergone nuclear transplant we used donor cells that expressed a histone H2B-cherry fluorescent fusion protein. Therefore the descendents of the nuclear transfer blastomere all possessed red fluorescent chromosomes and nuclei, allowing their identification within the embryo (Fig 1e–h). Upon release from mitotic arrest, both the transferred and the unmanipulated blastomeres completed mitosis and the embryos cleaved to the 4-cell stage. As expected, two cells within the embryo displayed H2B-cherry fluorescence, indicating that they carried the donor cell chromosomes (Fig. 1f). We found that these 4-cell embryos continued to develop efficiently in vitro to both the morula and blastocyst stages (Fig. 1g, h, Table 1).

Table 1.

Development after chromosome transfer into mitotic 2-cell stage blastomeres

| donor cell | # manipulated |

Cleaved to 4- cell stage (% of manipulated) |

morulae d4 post hCG |

blastocysts d4 post hCG |

Blastocysts with contribution from transferred blastomere % of cleaved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES cell | 294 | 223 (76) | 48 | 111 | 50 (111/223) |

| CD4+ T-lymphocyte (> 92% pure population) | 90 | 44 (48) | 23 | 8 | 18 (8/44) |

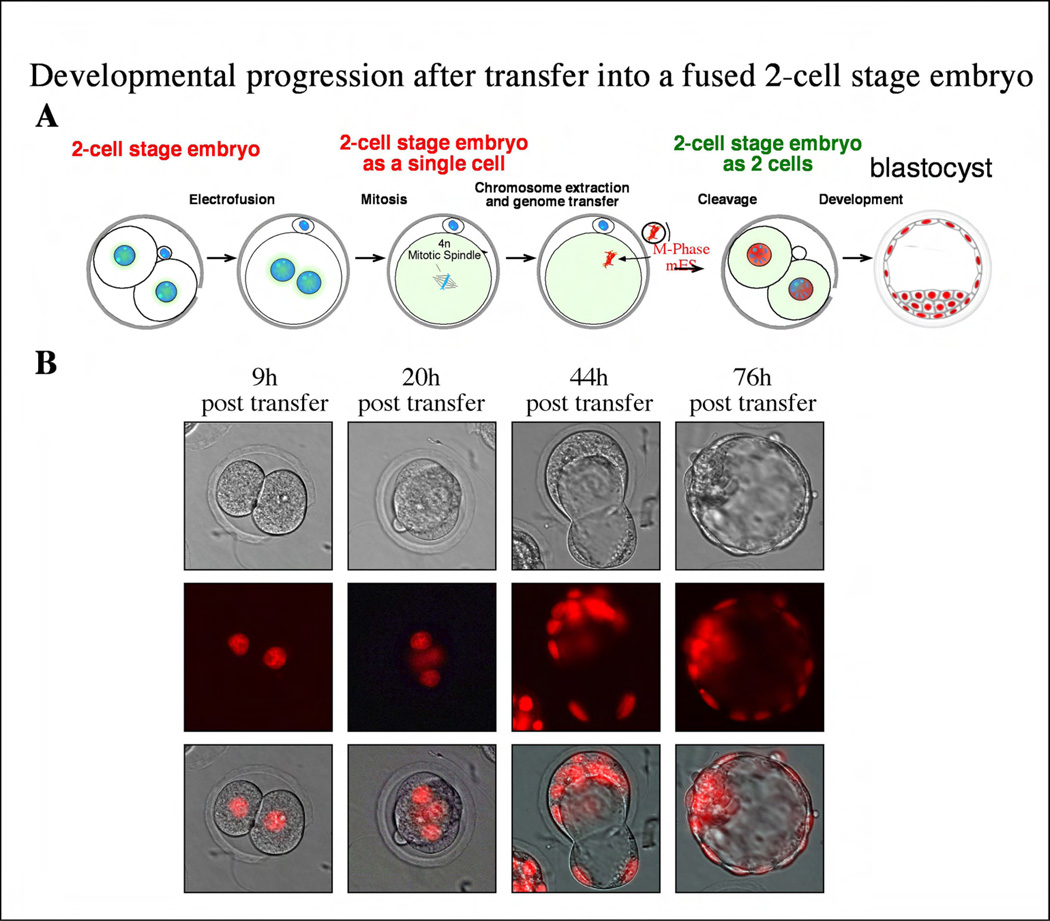

To exclude that this development depended on the presence of the non-manipulated blastomere, we generated embryos that were entirely derived from the donor genome. To do so, the two blastomeres were fused at the 2-cell stage, resulting in a tetraploid 2-cell stage embryo (Fig 2a). At mitosis, the tetraploid genome was removed and replaced by a diploid genome of an ES cell. These manipulated embryos cleaved to the 2-cell stage and efficiently proceeded in development to the blastocyst stage (8/11, or 72%). All nuclei of both trophectoderm and ICM expressed H2B-cherry, indicating that they were entirely derived from the injected donor chromosomes (Fig. 2b). Cavitation of the blastocyst is mediated by the expression of a set of novel genes that include a Na/K-ATPase and aquaporin which drive the movement of water across the trophectoderm cell layer to form a fluid-filled blastocoel [13]. Therefore, the ES donor cell had clearly been reprogrammed to express a set of novel genes to form a functional cell type.

Figure 2. Development after transfer into a fused 2-cell stage embryo.

A) Schematic representation of the experiment: 2-cell stage embryos are fused at interphase to form a tetraploid 1-cell stage embryo. These chromosomes will assemble in a spindle at the next mitosis, which can be removed and replace with a diploid genome. These embryos then cleave and develop to the balstocyst stage (B).

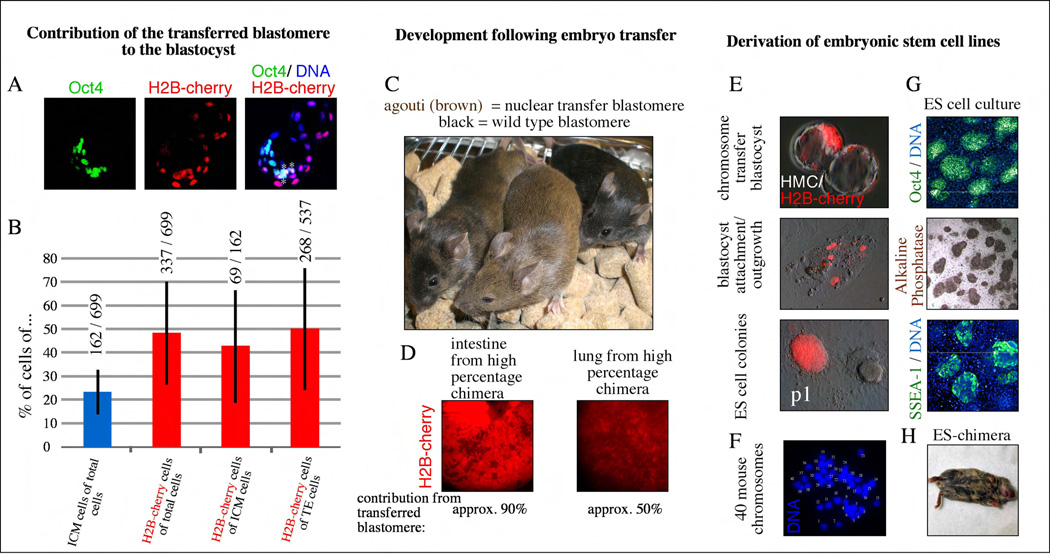

If the blastomere was able to reprogram the ES cell chromosomes, then the cells descended from the chromosome transfer blastomere might be expected to give rise to both the inner cell mass (ICM), from which ES cells are derived, and to the trophectoderm, which ES cells cannot normally generate. If reprogramming activities are no longer present in the mitotic cytoplasm of blastomeres, then blastomeres receiving ES cell chromosomes might only contribute to the ICM. To determine the relative contribution of the transferred blastomere to the trophectoderm and inner cell mass (ICM), blastocysts were stained with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 and with antibodies specific to the ICM specific protein Oct4 (Fig. 3a). Following staining, the number of red fluorescent cells in both the Oct4 positive (ICM) and Oct4 negative (trophectoderm) compartments were determined (Fig. 3b). We observed that in all blastocysts (11/11) the chromosome transfer blastomere contributed to both the ICM and trophectoderm, indicating that cellular reprogramming from an ES cell to trophectoderm identity had been allowed to occur. We further reasoned that if the reprogramming activities of the two-cell embryo were weaker or diminished, then the transferred blastomere might preferentially give rise to the ICM. However, we found no statistical evidence for such a bias. 50% of TE cells and 43% of ICM cells in the blastocyst were derived from the nuclear transfer blastomere (Fig. 3b). In addition and over all, we found that the total number of cherry positive cells derived from the manipulated blastomere was very similar or equal to the total number of cells from the untouched blastomere. This result suggests that the chromosome transfer method had little effect on the overall proportion of cells that the two blastomeres contributed to the blastocyst and that reprogramming was relatively complete.

Figure 3. Mice and stem cell lines produced by blastomere reprogramming.

a, Contribution of cells derived from the transferred blastomere marked by H2B-cherry to ICM and TE lineages at the blastocyst stage. Oct4 and H2B-cherry double positive cells are marked with a asterisk. b, quantification of H2B-cherry cells in TE and ICM (red columns). Total number of cells is indicated above each column. The total number of Oct4 positive cells as a marker of the ICM fate is 23% (blue column) at the expanded blastocyst stage. Bars indicate standard deviations. c, Contribution to full-term development of blastomeres transferred in mitosis. d, Contribution of cells derived from transferred (red) and nontransferred blastomere (dark) to a portion of the intestinal tube and the lung. e, Stem cells derived from chimeric blastocysts. P1= passage1 after manual picking of the ICM outgrowth. f, Karyotype of stem cells, showing a normal mouse karyotype of 40 chromosomes. Each chromosome is indicated with an arbitrary number of 1–40. g, Oct4 expression in embryonic stem cells derived after chromosome transfer, alkaline phosphatase staining, and SSEA-1 expression. h, chimeric mouse after injection of ES cells into BDF2 blastocysts. Tissue derived from the ES cell is brown, Tissue derived from the injected embryo is dark grey.

To test whether the chromosome transfer blastomere could further contribute to development after implantation, we transferred blastocysts to pseudopregnant recipient females, allowed the embryos to be carried to term and then assessed chimerism in the resulting offspring. In these experiments, the recipient embryos were isolated from a mouse strain with a black coat color while the donor cells were derived from a strain with an agouti (brown) coat. We performed embryo transfer with a total of 111 blastocysts that displayed red fluorescence and therefore had significant contribution from the nuclear transfer blastomere. After embryo transfer, a total of 7 pups were delivered by cesarean section, all of which survived to adulthood. Respiratory failure as observed after nuclear transfer into oocytes or zygotes was not observed [11, 14]. Five of these 7 mice had a black coat color, suggesting that they were predominantly or entirely derived from the unmanipulated recipient blastomere. However, in one animal, 30% of the coat was agouti and in the last animal, the coat color was exclusively agouti (Fig. 3c). The agouti coat color in these animals indicated that that they were chimeric “cloned” animals composed of both reprogrammed and normal cells.

To determine whether cells carrying the donor-cell genome had contributed widely to the development of the two chrimeric “cloned” animals, histological analysis was performed. We found that red fluorescent cells of donor origin, contributed significantly to the lungs, intestine and the skin (Fig. 3d). These results demonstrate that cells reprogrammed by blastomere nuclear transfer cannot only contribute significantly to a developing embryo but also that they are not necessarily outcompeted by normal embryonic cells.

Since the inception of in vitro fertilization, more than 400,000 embryos have been placed in frozen storage by couples undergoing assisted reproduction treatment [15]. Recent studies suggest that the vast majority of these embryos remain in storage even though they are no longer needed for reproductive purposes. Furthermore, 60% of the couples controlling the disposition of these embryos would prefer to have them donated for stem cell research rather than see them donated to another couple or simply discarded [16]. Although a small percentage of human embryos are frozen at the one cell stage a majority of embryos are frozen during cleavage stage of preimplantation development. Therefore, if methods for reprogramming somatic cells using chromosome transfer into blastomeres could be perfected, a conservative estimate would suggest that more than 100,000 embryos would be readily available for human reprogramming attempts.

However, if blastomere nuclear transfer is to be useful for the production of genetically tailored human embryonic stem cell lines, then it must be shown that ES cell lines can be derived from blastocysts that result from this approach and it must be demonstrated that blastomeres can reprogram terminally differentiated adult cells.

To determine whether ES cell lines could be derived from embryos created by blastomere chromosome transfer, 14 chimeric blastocysts were placed in culture on mouse embryonic fibroblasts for attempts at ES cell line derivation. Each of the embryos adhered to the feeder layer and 7 gave rise to ICM outgrowths. We found that attachment sites and ICM outgrowths consisted of both red fluorescent cells derived from the nuclear transfer blastomere, as well as non-fluorescent cells derived from the unmanipulated blastomere (Fig. 3e). 6 of the 7 blastocysts gave rise to ES cell cultures and 3 of these contained ES cells derived from both the chromosome transfer blastomere (Cherry positive colony)(Fig. 3e). When red fluorescent colonies in these cultures were manually picked and expanded into pure cultures, PCR confirmed that they contained the donor genome. Furthermore, nuclear transfer ES cell lines expressed the pluripotency transcription factor Oct4 (Fig. 3g) and contained a normal karyotype of 40 mouse chromosomes (Fig. 3f). And when injected into blastocysts, these ES cells gave rise to chimeric mice (Fig. 2h).

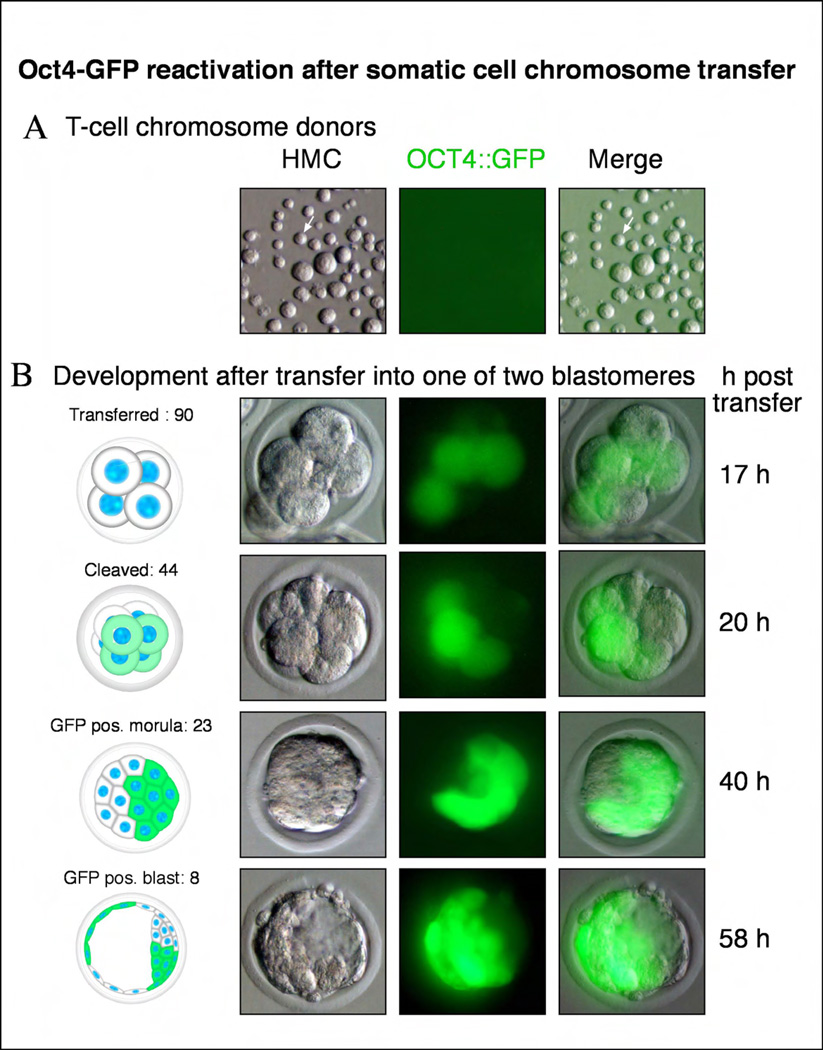

We next sought to demonstrate that the blastomeres of the two-cell stage embryo could reprogram a terminally differentiated adult cell. T- lymphocytes are terminally differentiated cells, which can be reprogrammed, but only at a very low efficiency [17, 18]. We therefore chose T-lymphocytes as donor cells because their reprogramming would be a stringent assay for reprogramming. To assess reprogramming of the T-cell genome, we used donor cells carrying a transgenic reporter in which regulatory sequences from the Oct4 gene control expression of GFP (Oct4::GFP). This transgene is not expressed in somatic tissues, which are therefore non-fluorescent. However, recent reprogramming studies with defined transcription factors, cell fusion and nuclear transfer have each demonstrated that reactivation of the Oct4::GFP reporter is a rigorous indicator of complete reprogramming [11, 19, 20].

CD4+ T-cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of transgenic Oct4::GFP mice as described previously [21]. FACS analysis of these preparations confirmed that more than 92% of the cells were indeed CD4+ T-lymphocytes. For T-cell chromosomes transfer, cultures of purified T-cells were stimulated to enter mitosis with antibodies directed against CD3ε and CD28, and arrested there with nocadazole. Like other somatic cells, T-cells did not express Oct4::GFP (Fig. 4a). As with ES donor cells, we found that mitotic T-cell chromosomes could be readily transferred into embryonic blastomeres at the two-cell stage. Following chromosome transfer, embryos efficiently underwent cleavage and could develop to the blastocyst stage (Table 1). 20 hours after chromosome transfer, we found that 24/67 embryos developed to the 6 to 8-cell stage and that 24/24 (100%) of these embryos contained cells expressing GFP. Oct4::GFP expression indicated that these cells carried the T-cell donor chromosomes and that these chromosomes had been successfully reprogrammed (Fig. 4b). After chromosome transfer, we found that Oct4::GFP continued to be highly expressed within a subset of cells in morula stage and blastocyst stage embryos, indicating that reprogramming was stable (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Blastomeres can reprogram terminally differentiated T-cells.

a, Mitotic CD4+ T-cell population. Donor T-cells do not show expression of an Oct4::GFP transgene. b, Upon transfer of a mitotic T cell into a blastomere in mitosis, development occurs and the Oct4::GFP transgene is reactivated within hours after transfer. Developmental progression to the blastocyst stage.

In summary, our chromosome transfer studies demonstrate that reprogramming activities persist in the blastomeres of cleavage stage embryos and that these activities are sufficient to allow the derivation of ES cell lines, the generation of chimeric “cloned” animals and the reprogramming of terminally differentiated nuclei. This is a particularly interesting finding because the proteins and transcripts within the two-cell blastomeres, just before their mitotic division to the 4-cell stage, are substantially different from those present in either the fertilized zygote or oocyte [22, 23]. We found that Oct4::GFP was reactivated within twenty hours following lymphocyte chromosome transfer at roughly the same time and stage that it would have been activated in a normally fertilized embryo. Taken together, these results imply that the blastomeres of a two-cell embryo can reprogram the incoming donor chromosomes to a state similar to that of the recipient blastomere. The reprogrammed cell then goes forward from that developmental stage, rather than reverting to some more primitive, oocyte or zygote-like transcriptional program before proceeding.

The finding that oocytes, zygotes, embryonic blastomeres and ES cells can each reprogram differentiated cells indicates that reprogramming activities persist through preimplantation development. When our results are combined with the recent observations that cell type specific transcription factors can exact reprogramming [24, 25] it suggests, that if the proper nuclear or chromosome transfer method could be developed, almost any cell might be reprogrammed into another. In fact it may be that the reprogramming activities in a particular cell type are one and the same with the transcription factors that specify its identity.

The generation of human ES cell lines by nuclear transfer is still a high priority. Only isogenic cell lines produced by various reprogramming approaches will allow the effectiveness and utility of the different methods to be accurately compared. Our results using mouse embryos suggest that cleavage stage human embryos are an important unexplored resource for nuclear transfer studies. Human embryos are commonly frozen at the 4 to 8 cell stage. Importantly, a single blastomere from a 4-cell human embryo is roughly the same size as the mouse zygote and a blastomere from a human 8-cell embryo is similar in diameter to a blastomere from the 2-cell mouse embryo. Thus, micromanipulation approaches similar to those described in this study may be feasible with the most readily available discarded human embryos. Sourcing this material for nuclear transfer studies will be considerably more routine than obtaining fresh human oocytes, or even frozen zygotes.

Experimental Procedures

The method followed largely the protocol of chromosome transfer into mitotic mouse zygotes [11]. Briefly, zygotes were collected from mated BDF1 females 20–24h post hCG and cultured to the 2-cell stage. 48h – 50h post hCG 2-cell stage embryos were cultured in the presence of 0.2µg/ml nocodazole to arrest them in mitosis. For removal of the donor cell genome, mouse embryos were placed on the heated stage of a microscope in HCZB with slightly lower nocodazole concentrations, between 0.02–0.04 µg/ml, and high cytochalasinB concentrations of about 10µg/ml to maximize fluidity of the cytoplasm. Under these low nocodazole concentrations mouse blastomeres arrest in mitosis with a spindle (Supplemental Figure 1) that can conveniently be removed (Supplemental Movie). Enucleation and transfer of a new genome was done between 50 and 57h post hCG (Supplemental Movie). The survival rate of the transfer was 136/244 (56%). After manipulation, embryos were cultured in KSOM at 37deg. C in 5% CO2. Male ES cells transgenic for pCAGGS:H2B-cherry were used as donors.

Equipment used consisted of a Nikon microscope equipped with a Narishige micromanipulator. Details of the microscope setup are essentially as after nuclear transfer into mouse [26]oocytes [27].

Mouse blastocysts were stained using the Oct3/4 antibody (Santa Cruz sc5279) at a dilution of 1:200. Cell numbers were quantified with the Imaris program.

CD4+ T-cells were isolated as previously described [21]. Briefly, total splenocytes and lymph node cells were harvested from 6–10 week old B6jcBA-Tg(Pou5fI-EGFP)2Mnn/J or H2B-GFP transgenic mice. The cells were labeled with an antibody cocktail, consisting of antibodies against CD8, CD11b, CD45R/B220, CD49b, and TER-119 (IMag Mouse CD4+ T Lymphocyte Enrichment Set – DM, BD Pharmingen). In order to enrich for CD4+ T cells, negative selection was performed. Labeled cells were magnetically depleted according to the protocol of the supplier. The negative selection was performed a second time on the enriched fraction in order to increase purity of CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells purity was higher than 92 % and the patterns of flow cytometry to check for quality of the enrichment was consistent with the data shown in the supplier's technical data sheet. Isolated CD4+ T cells were grown in suspension culture in 6-well plates with a density of a million cells per well in 5 ml/well of complete RPMI media. The plates were pre-coated with 1 µg/ml of each anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 antibodies to stimulate expansion of T-cells. 1–3 days after culture, T-cells were at maximal rates of proliferation and were arrested in mitosis by incubation with 0.1µg/ml nocodazole for 8 hours. Mitotic T-cells (1–10% of all T cells) were selected for transfer into blastomeres. Experiments with animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Harvard University/Faculty of Arts and Sciences IACUC for the humane care and use of animals in research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Garrett Birkhoff for help with the preparation of Figures and Inna Tabansky for help with the Imaris imaging software. This work was supported by a seed grant from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, NIH grant R01 HD045732-03 to K.E., as well as the Stowers Medical Institute D.E. is a Stan and Fiona Druckenmiller/NYSCF postdoctoral fellow. K.E. is a fellow of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Egli D, Birkhoff G, Eggan K. Mediators of reprogramming: transcription factors and transitions through mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Nuclear reprogramming and pluripotency. Nature. 2006;441:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/nature04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA, Svendsen CN. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, Goland R, et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Generated from Patients with ALS Can Be Differentiated into Motor Neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Giorgio FP, Boulting GL, Bobrowicz S, Eggan KC. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Motor Neurons Are Sensitive to the Toxic Effect of Glial Cells Carrying an ALS-Causing Mutation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrath J, Solter D. Inability of mouse blastomere nuclei transferred to enucleated zygotes to support development in vitro. Science. 1984;226:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.6542249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao S, Gasparrini B, McGarry M, Ferrier T, Fletcher J, Harkness L, De Sousa P, Wilmut I. Germinal vesicle material is essential for nucleus remodeling after nuclear transfer. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:928–934. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakayama T, Tateno H, Mombaerts P, Yanagimachi R. Nuclear transfer into mouse zygotes. Nat Genet. 2000;24:108–109. doi: 10.1038/72749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roh S, Guo J, Malakooti N, Morrison JR, Trounson AO, Du ZT. Birth of rats following nuclear exchange at the 2-cell stage. Zygote. 2003;11:317–321. doi: 10.1017/s0967199403002375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsunoda Y, Yasui T, Shioda Y, Nakamura K, Uchida T, Sugie T. Full-term development of mouse blastomere nuclei transplanted into enucleated two-cell embryos. J Exp Zool. 1987;242:147–151. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402420205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egli D, Rosains J, Birkhoff G, Eggan K. Developmental reprogramming after chromosome transfer into mitotic mouse zygotes. Nature. 2007;447:679–685. doi: 10.1038/nature05879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato Y, Tsunoda Y. Synchronous division of mouse two-cell embryos with nocodazole in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1992;95:39–43. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0950039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson AJ, Barcroft LC. Regulation of blastocyst formation. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D708–D730. doi: 10.2741/watson. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggan K, Akutsu H, Loring J, Jackson-Grusby L, Klemm M, Rideout WM, 3rd, Yanagimachi R, Jaenisch R. Hybrid vigor, fetal overgrowth, and viability of mice derived by nuclear cloning and tetraploid embryo complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6209–6214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101118898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradi D. Parents Torn Over Fate of Frozen Embryos. New York Times: 2008. p. A26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyerly AD, Steinhauser K, Voils C, Namey E, Alexander C, Bankowski B, Cook-Deegan R, Dodson WC, Gates E, Jungheim ES, et al. Fertility patients' views about frozen embryo disposition: results of a multi-institutional U.S. survey. Fertil Steril: 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Monoclonal mice generated by nuclear transfer from mature B and T donor cells. Nature. 2002;415:1035–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Mouse cloning with nucleus donor cells of different age and type. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:376–383. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<376::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boiani M, Eckardt S, Scholer HR, McLaughlin KJ. Oct4 distribution and level in mouse clones: consequences for pluripotency. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1209–1219. doi: 10.1101/gad.966002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brambrink T, Foreman R, Welstead GG, Lengner CJ, Wernig M, Suh H, Jaenisch R. Sequential expression of pluripotency markers during direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinohara ML, Kim JH, Garcia VA, Cantor H. Engagement of the type I interferon receptor on dendritic cells inhibits T helper 17 cell development: role of intracellular osteopontin. Immunity. 2008;29:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng F, Baldwin DA, Schultz RM. Transcript profiling during preimplantation mouse development. Dev Biol. 2004;272:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latham KE, Garrels JI, Chang C, Solter D. Quantitative analysis of protein synthesis in mouse embryos. I. Extensive reprogramming at the one- and two-cell stages. Development. 1991;112:921–932. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howlett SK, Barton SC, Surani MA. Nuclear cytoplasmic interactions following nuclear transplantation in mouse embryos. Development. 1987;101:915–923. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.4.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egli D, Eggan K. Nuclear transfer into mouse oocytes. J Vis Exp. 2006:116. doi: 10.3791/116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.