Abstract

Background:

We evaluated the prognostic importance of DNA ploidy in stage I and II endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EAC) of the endometrium with a focus on DNA index.

Patients and methods:

High-resolution DNA ploidy analysis was carried out in tumor material from 937 consecutive patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I and II EAC of the endometrium.

Results:

Patients with diploid (N = 728), aneuploid tumor with DNA index ≤1.20 (N = 118), aneuploid tumors with DNA index >1.20 (N = 39) and tetraploid tumor (N = 52) had 5-year recurrence rates 8%, 14%, 20% and 12%, respectively. Patients with aneuploid tumor with DNA index >1.20 had a poorer 5-year progression-free survival (67%) and overall survival (72%) compared with the patients with aneuploid tumor with DNA index ≤1.20 (81% and 89%, respectively). Aneuploid tumors with DNA index ≤1.20 relapsed mainly in the vagina and pelvis, whereas aneuploid tumors with DNA index >1.20 relapsed predominantly outside pelvis.

Conclusions:

The recurrence risk for the patients with aneuploid tumor is higher than the patients with diploid tumor in EAC of the endometrium. Based on DNA index with cut-off 1.20, aneuploid tumors can be separated into two subgroups with different recurrence pattern and survival.

Keywords: DNA index, DNA ploidy, endometrial carcinoma, EAC, image cytometry

introduction

The important prognostic factors for patients with endometrial carcinoma include the pathological stage of the disease, the extent of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and histological subtype [1,2]. In addition to these factors, DNA ploidy of the tumor has been reported as a prognostic factor [3–6], even in routine diagnostic setting [7]. The patients with diploid tumor have better survival compared with those with aneuploid tumor. In addition, DNA ploidy has been used to identify a subgroup of patients in need of adjuvant therapy [8–10].

Modern high-resolution image cytometry enables better detection of near-diploid peaks. This is usually difficult in flow cytometric DNA ploidy analysis from paraffin-embedded material [11], the method used in the majority of studies [5, 7, 8, 10, 12–14]. Whether minor deviation in tumor cell DNA content has a clinical relevance is still unknown.

Endometrial carcinoma is a histologically heterogeneous entity ranging from less-aggressive tumor such as endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EAC) grade 1 to highly aggressive malignancy such as serous adenocarcinoma [15]. In most of the DNA ploidy studies, all the histological subtypes are included in the analyses making the interpretation of DNA ploidy findings in a definite subtype difficult [3, 16, 17]. Furthermore, DNA ploidy statuses and the DNA index (DI) of aneuploid tumor are associated with the histological subtypes [18]. In order to evaluate the prognostic importance of DNA ploidy and DI, we have studied a large series of tumors from patients with EAC in stage I and II with a follow-up of at least 4 years.

patients and methods

We have carried out a study of the consecutive patients with endometrial carcinoma who were referred to the Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH), Oslo University Hospital from September 1998 to February 2006. The NRH is one of the four teaching cancer centers for gynecologic oncology and serves mainly as the regional cancer hospital for the Southeast region of Norway covering ∼56% of the total population of Norway. The samples for DNA ploidy analysis were prospectively collected. Based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections, the most representative block containing tumor from curettage or hysterectomy specimens were selected. Representative areas (most atypical, best preserved, without necrosis and blood) were marked and processed for DNA ploidy analysis. Only the cases with stage I and II disease with histological subtype EAC were included in the study. Patients with additional cancer, cases without representative tissue in the control H&E section, cases with diploid tumors with a high coefficient of variation (CV) of the peak (>5) were excluded. Furthermore, five patients with an aneuploid tumor diagnosed by 5c exceeding rate (5c ER) >1% (percentage of nuclei with a DNA content 2.5 times more than diploid nuclei) and one patient with a polyploid tumor were not included in the analysis due to the low numbers. Finally, 937 patients remained for the analyses. The information on stage [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 1988], recurrence and LVI was obtained from the clinical and pathology reports. The data on death were acquired from the Center Bureau of Statistics, which registers all deaths based on the death certificates transmitted by the patients’ physicians. DNA ploidy analysis was carried out in hysterectomy specimen in 686 and in curettage specimen in 251 cases. The treatment protocol for the period was abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy were carried out if suspicious of metastasis. Additional radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy were given to 62 and 20 patients with high-risk, respectively. DNA ploidy diagnosis was not taken into consideration for the adjuvant therapy of the patients. The patients with recurrence were treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or surgery depending on the localization of the recurrence and the hormone receptors’ expression of the tumor. Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Southeastern Norway.

histology of the tumors

Without knowledge of the outcome, all histology slides from the area, from which DNA ploidy was carried out, were reviewed by two pathologists (MP and BR). In discordant cases, a third gynecologic pathologist (VA) was consulted in order to reach consensus. The tumors were classified and graded according to World Health Organization recommendation [15]. We used reviewed diagnosis for the analysis as it has been shown to be prognostically better than initial routine diagnosis [12].

DNA image cytometry

The monolayers, prepared from 50-μm sections from paraffin-embedded blocks, were stained by Feulgen method as described in detail previously [18]. The DNA content in nuclei was measured using Ploidy Work Station (Room 4, Kent, UK), which consists of Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 546-nm green filter and a high-resolution digital camera. Integrated optical density (IOD) was calculated by multiplying the measured optical density and the area of each nucleus. The nuclear images were edited and grouped into different galleries for tumor nuclei, reference nuclei and discarded nuclei. DNA ploidy histograms were created from IOD of the nuclei using PWS Classifier (Room 4, Kent, UK). The mean IOD of a non-diploid peak was divided by the mean IOD of the diploid peak to compute DI. Using the reference nuclei as an internal diploid control, DNA ploidy histograms were classified into diploid, aneuploid, tetraploid and polyploid according to the criteria described earlier [18]. In order to find out the prognostic importance of near-diploid peaks, aneuploid tumors were further grouped into aneuploid tumors with DI 1.06–1.20 and aneuploid tumors with DI >1.20. DI, 5c ER and 9c ER were registered additionally.

reproducibility of DNA ploidy histogram evaluation

To evaluate the reproducibility of DNA ploidy histogram evaluation, 102 cases (∼10%) were randomly selected, and the DNA ploidy results were evaluated by another pathologist (BR).

statistical analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to recurrence or 31 August 2010 and both recurrence and death due to any cause were considered as events. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to death or 15 December 2010 and death due to any cause was considered as an event. The Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test were used for univariate survival analysis. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with backward stepwise elimination was used for multivariate survival analysis. Variables with P < 0.20 in univariate survival analysis were included in the model. Chi-square test was used to test the association between DI and histological grades. Fisher’s exact test was carried out to test the association between subgroups of aneuploid tumors and the site of recurrences. The reproducibility of DNA ploidy diagnosis and DI were evaluated by using Cohen’s kappa coefficient and intraclass correlation coefficient. CV of the IOD of diploid peaks was calculated for the quality assurance of histograms. All statistical tests were two-sided and P-values ≤0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

results

patient characteristics

The median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 64 years (mean 64, range 35–95 years). There were 181 patients in stage IA, 467 in stage IB, 164 in IC, 73 in IIA and 52 in IIB. By histological evaluation, 613 tumors were grade 1, 237 were grade 2 and 87 were grade 3 (Table 1). LVI was present in 16% cases (147 out of 905). In 32 cases, LVI data were not available. Both pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy were carried out in 72 (8%) and only pelvic lymphadenectomy was carried out in 159 (17%) patients. The recurrences were detected in the vagina (41 cases), in the pelvis (18 cases) and outside pelvis in 36 cases.

Table 1.

Recurrence rate, PFS and OS based on various prognostic factors in patients with stage I and II endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium

| Variables | Categories | Number of patients (%) | Number of recurrences (%) | Number of deaths (%) | Recurrence site | 5-year recurrence rate ± SE (%) | 5-year PFS | 5 year OS | ||||

| Vagina (%) | Pelvis (%) | Outside pelvis (%) | PFS ± SE (%) | P-valuea | OS ± SE (%) | P-valuea | ||||||

| Age (years) | <65 | 485 (52) | 28 (6) | 34 (7) | 10 (36) | 3 (11) | 15 (54) | 5 ± 1 | 93 ± 1 | <0.01 | 96 ± 1 | <0.01 |

| ≥65 | 452 (48) | 67 (15) | 156 (35) | 31 (46) | 15 (22) | 21 (31) | 15 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 82 ± 2 | |||

| FIGO stage | IA | 181 (19) | 1 (1) | 24 (13) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 ± 1 | 94 ± 2 | <0.01 | 94 ± 2 | <0.01 |

| IB | 467 (50) | 46 (10) | 79 (17) | 24 (52) | 7 (15) | 15 (33) | 9 ± 1 | 86 ± 2 | 91 ± 1 | |||

| IC | 164 (18) | 22 (13) | 53 (32) | 12 (55) | 3 (14) | 7 (32) | 14 ± 3 | 76 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | |||

| IIA | 73 (8) | 15 (21) | 22 (30) | 3 (20) | 5 (33) | 7 (47) | 20 ± 5 | 68 ± 5 | 81 ± 5 | |||

| IIB | 52 (6) | 11 (21) | 12 (23) | 2 (18) | 3 (27) | 6 (55) | 20 ± 6 | 77 ± 6 | 85 ± 5 | |||

| Grade | 1 | 613 (65) | 47 (8) | 99 (16) | 23 (49) | 12 (26) | 12 (26) | 7 ± 1 | 88 ± 1 | <0.01 | 92 ± 1 | <0.01 |

| 2 | 237 (25) | 30 (13) | 64 (27) | 14 (47) | 3 (10) | 13 (43) | 12 ± 2 | 81 ± 3 | 86 ± 2 | |||

| 3 | 87 (9) | 18 (21) | 27 (31) | 4 (22) | 3 (17) | 11 (61) | 22 ± 5 | 67 ± 5 | 77 ± 5 | |||

| LVIb | Absent | 758 (84) | 62 (8) | 131 (17) | 32 (52) | 11 (18) | 19 (31) | 8 ± 1 | 86 ± 1 | <0.01 | 91 ± 1 | <0.01 |

| Present | 147 (16) | 31 (21) | 53 (36) | 8 (26) | 6 (19) | 17 (55) | 21 ± 3 | 71 ± 4 | 78 ± 3 | |||

| Total | 937 (100) | 95 (10) | 190 (20) | 41 (43) | 18 (19) | 36 (38) | 10 ± 1 | 84 ± 1 | 89 ± 1 | |||

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SE, standard error.

Overall P-value by log-rank test.

Data not available in 32 cases.

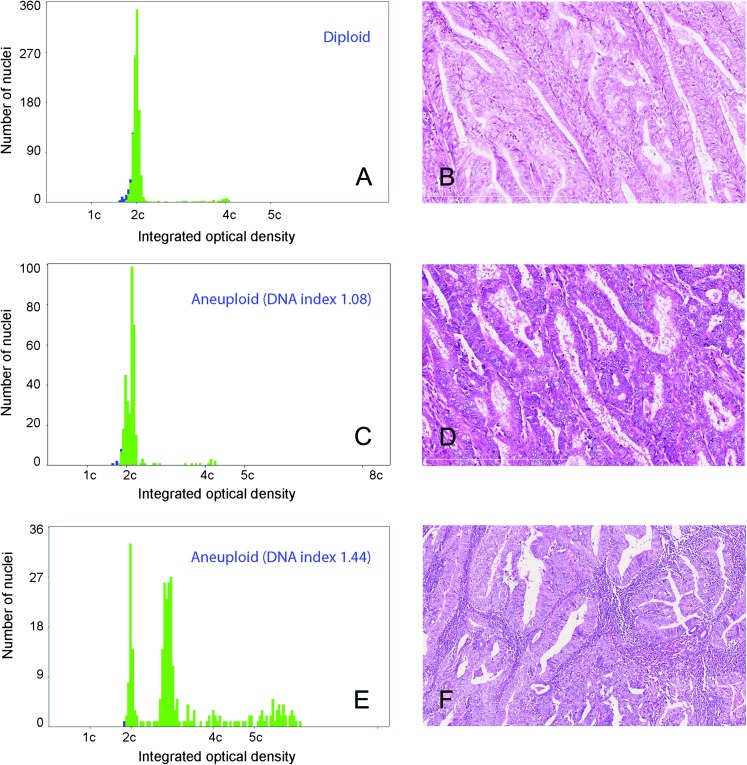

image cytometric DNA ploidy

The mean and median CV of the diploid peak in the DNA ploidy analyses were 2.9 and 2.8, respectively. The mean number of nuclei analyzed was 601 (median 300, range 99–1620). Most of the tumors were diploid (728 cases, 78%). Among the 157 aneuploid tumors, 118 (13%) had a DI between 1.06 and 1.20 and 39 (4%) had a DI >1.2 (Table 2, Figure 1), whereas 52 (6%) were tetraploid. In 867 cases, 5c ER was <1% and ≥1% in 70 cases. Tumors with DI ≤1.20 were mainly found in histological grade 1 and 2, whereas those with DI >1.2 were more frequent in grade 3 (P < 0.01, Table 3).

Table 2.

Recurrence rate, PFS and OS of patients with stage I and II endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium based on DNA ploidy

| Variables | Categories | Number of patients (%) | Number of recurrences (%) | Number of deaths (%) | Recurrence site | 5-year recurrence rate ± SE (%) | 5-year PFS | 5-year OS | ||||

| Vagina (%) | Pelvis (%) | Outside pelvis (%) | PFS ± SE % | P-valuea | OS ± SE % | P-valuea | ||||||

| DNA ploidy | Diploid | 728 (78) | 63 (9) | 136 (19) | 29 (46) | 13 (21) | 21 (33) | 8 ± 1 | 85 ± 1 | 0.03 | 90 ±1 | 0.02 |

| Aneuploid (DI ≤1.20) | 118 (13) | 18 (15) | 27 (23) | 9 (50) | 3 (17) | 6 (33) | 14 ± 3 | 81 ± 4 | 89 ± 3 | |||

| Aneuploid (DI >1.20) | 39 (4) | 8 (21) | 14 (36) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 6 (75) | 20 ± 7 | 67 ± 8 | 72 ± 7 | |||

| Tetraploid | 52 (6) | 6 (12) | 13 (25) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 12 ± 5 | 83 ± 5 | 85 ±5 | |||

| Total | 937 (100) | 95 (10) | 190 (20) | 41 (43) | 18 (19) | 36 (38) | 10 ± 1 | 84 ± 1 | 89 ± 1 | |||

DI, DNA index; OS, overall survival; PSF, progression-free survival; SE, standard error.

Overall P-value by log-rank test.

Figure 1.

A DNA histogram showing a diploid tumor and corresponding histology from a patient, who had disease-free survival for >5 years (A, B). DNA ploidy histogram and histology of a patient with aneuploid tumor with DNA index (DI) 1.08. The patient had recurrence after 8 months (C, D). An aneuploid tumor with DI 1.44, the patient had recurrence in liver, upper abdominal cavity and inguinal lymph nodes after 15 months (E, F).

Table 3.

DNA ploidy subgroups in relation to other parameters in endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma

| Parameters | DNA ploidy | |||||

| Diploid (%) | Aneuploid, DI ≤1.20 (%) | Aneuploid, DI >1.20 (%) | Tetraploid (%) | Total | ||

| Age | <65 | 384 (79) | 58 (12) | 16 (3) | 27 (6) | 485 |

| ≥65 | 344 (76) | 60 (13) | 23 (5) | 25 (5) | 452 | |

| Grade | 1 | 517 (84) | 75 (12) | 9 (2) | 12 (2) | 613 |

| 2 | 169 (71) | 37 (16) | 15 (6) | 16 (7) | 237 | |

| 3 | 42 (48) | 6 (7) | 15 (17) | 24 (28) | 87 | |

| Stage | IA | 140 (77) | 22 (12) | 7 (4) | 12 (7) | 181 |

| IB | 359 (77) | 64 (14) | 17 (4) | 27 (6) | 467 | |

| IC | 134 (82) | 15 (9) | 10 (6) | 5 (3) | 164 | |

| IIA | 55 (75) | 11 (15) | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 73 | |

| IIB | 40 (77) | 6 (12) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 52 | |

| LVIa | Absent | 598 (79) | 94 (12) | 25 (3) | 41 (5) | 758 |

| Present | 101 (69) | 22 (15) | 14 (10) | 10 (7) | 147 | |

| Specimen | Curettage | 193 (77) | 20 (8) | 12 (5) | 26 (10) | 251 |

| Hysterectomy | 535 (78) | 98 (14) | 27 (4) | 26 (4) | 686 | |

DI, DNA index; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

Data not available in 32 cases.

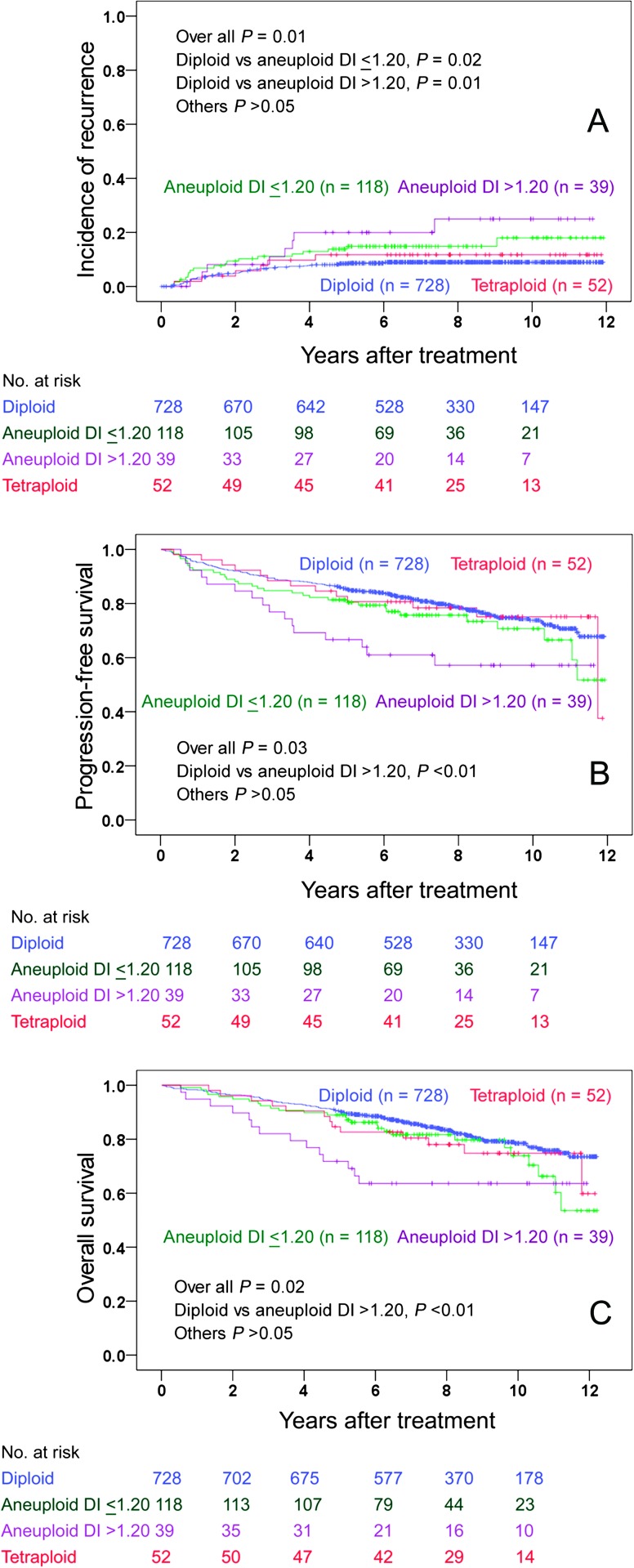

survival analyses

At the date of last follow-up, 95 patients had recurred and 190 were dead due to any cause. The 5-year recurrence rate, PFS and OS ± standard error for all patients were 10 ± 1%, 84 ± 1% and 89 ±1%, respectively. The 5-year recurrence rates for diploid, aneuploid with DI ≤1.20, aneuploid with DI >1.20 and tetraploid tumors were 8%, 14%, 20% and 12%, respectively (Table 2). Diploid and aneuploid tumors with DI ≤1.20 relapsed mainly in the vagina (Table 2). In contrast, aneuploid tumor with DI >1.20 relapsed outside pelvis (six cases, Table 2). The association of recurrence site and DI of aneuploid tumors was not statistically significant in spite of a big difference in proportions (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.09). This was probably due to small numbers. The patients with aneuploid tumor with DI >1.20 had significantly poorer PFS and OS than the patients with diploid tumor (Figure 2). Age (P <0.01), FIGO stage (P < 0.01), grade (P < 0.01), LVI (P < 0.01) and DNA ploidy (P < 0.03) were significantly associated with both PFS and OS (log-rank test). In multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazard regression, age (P < 0.01), histological grade (P = 0.01), LVI (P < 0.01) and FIGO stage (P < 0.01) were prognostic factors for PFS, whereas age (P < 0.01), LVI (P < 0.01) and grade (P = 0.03) were prognostic for OS (Table 4). We additionally carried out multivariate analysis using recurrence as an endpoint. Only age (P < 0.01), FIGO stage (P < 0.01), grade (P = 0.04) and LVI (P = 0.03) were retained in the model (Table 4). Dichotomized 5c ER with cut-off 1% showed borderline prognostic significance for PFS in the univariate analysis (P = 0.07). Furthermore, we analyzed OS in patients with recurrence in order to evaluate the response to salvage therapy in different DNA ploidy subgroups. The overall P-value for all subgroups was 0.04 (log-rank test). When the subgroups were tested pairwise, only the patients with diploid and tetraploid tumors differed significantly (P < 0.01). No significant difference in OS in the patients with recurrence was observed between diploid, aneuploid with DI 1.06–1.20 and aneuploid with DI >1.20 subgroups.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan–Meier curves of cumulative incidence of recurrence (A), progression-free survival (B) and overall survival (C) of different DNA ploidy subgroups.

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses of prognostic parameters in stage I and II endometrioid adenocarcinoma

| Recurrence |

Progression-free survival |

Overall survival |

||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age <65 | 1 | <0.01 | 1 | <0.01 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Age ≥65 | 2.52 (1.60–3.96) | 4.46 (3.22–6.19) | 5.77 (3.97–8.38) | |||

| No LVI | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | <0.01 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Presence of LVI | 1.74 (1.06–2.86) | 1.65 (1.17–2.32) | 2.16 (1.54–3.04) | |||

| Grade 1 | 1 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Grade 2 | 1.30 (0.80–2.11) | 0.29 | 1.30 (0.95–1.78) | 0.10 | 1.41 (1.01–1.97) | 0.04 |

| Grade 3 | 2.17 (1.2–3.94) | 0.01 | 1.84 (1.22–2.77) | <0.01 | 1.70 (1.09–2.67) | 0.02 |

| Stage IA | 1 | <0.01 | 1 | <0.01 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Stage IB | 14.93 (2.05–108.65) | <0.01 | 1.38 (0.87–2.19) | 0.17 | 0.98 (0.61–1.58) | 0.94 |

| Stage IC | 14.96 (1.99–112.72) | <0.01 | 1.70 (1.03–2.83) | 0.04 | 1.25 (0.74–2.12) | 0.41 |

| Stage IIA | 34.75 (4.56–264.53) | <0.01 | 2.68 (1.53–4.72) | <0.01 | 1.64 (0.90–2.99) | 0.11 |

| Stage IIB | 23.11 (2.91–183.56) | <0.01 | 1.67 (0.86–3.27) | 0.13 | 0.93 (0.44–1.99) | 0.86 |

| Diploid | 1 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.69 | |

| Aneuploid (DI ≤1.20) | 1.65 (0.97–2.82) | 0.07 | 1.16 (0.79–1.71) | 0.44 | 1.15 (0.75–1.75) | 0.53 |

| Aneuploid (DI >1.20) | 1.59 (0.71–3.53) | 0.26 | 1.28 (0.73–2.23) | 0.39 | 1.41 (0.77–2.55) | 0.26 |

| Tetraploid | 0.92 (0.37–2.27) | 0.85 | 0.78 (0.43–1.42) | 0.42 | 1.05 (0.57–1.92) | 0.88 |

CI, confidence interval; DI, DNA index; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; OR, Odds ratio.

We further evaluated whether the specimen used for DNA ploidy analysis has any impact in prognostication. DNA ploidy results from hysterectomy specimen (P < 0.01) were superior compared with results from curettage specimen (P = 0.76) to prognosticate biological behavior in patients with this tumor.

reproducibility of the DNA ploidy histogram

In the reproducibility study of 102 samples, DNA ploidy diagnoses were identical in 97 cases with a very good agreement (Cohen κ = 0.89). Intraclass correlation coefficient for DI was 0.94.

discussion

The DNA ploidy has repeatedly been reported as an important prognostic factor for patients with endometrial carcinoma by many investigators [3, 5, 6, 13]. Generally, the DNA ploidy results are grouped into two, namely, diploid and non-diploid (aneuploid and tetraploid together) [8, 19–21] or euploid (diploid and tetraploid together) and aneuploid [12]. We, earlier, observed that the histological subtypes of endometrial carcinoma associate with DNA ploidy status and DI. Most of the aneuploid EAC had DI ≤1.20, whereas aneuploid serous adenocarcinoma had DI >1.60. Furthermore, bimodal distribution of DI was seen in endometrial carcinoma [18]. Therefore, we identified four distinct DNA ploidy groups, namely, diploid, tetraploid, aneuploid tumors with a peak near to diploid peak (DI 1.06 to 1.20) and aneuploid tumors with a peak toward tetraploid peak (DI >1.20). The prognostic importance of these subgroups of DNA ploidy has not been studied. Moreover, endometrial carcinoma is a heterogeneous cancer with different aggressiveness ranging from less-aggressive tumor as EAC grade 1 to highly aggressive tumors such as serous and clear-cell adenocarcinomas. EAC is a different entity than serous and clear-cell adenocarcinomas regarding morphology [15], molecular expression [4], oncogenesis [22] and prognosis [23–25]. We, therefore, analyzed a relatively large series of EACs of the endometrium and found that these four DNA ploidy subgroups have different recurrence and survival patterns. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report analyzing the prognostic importance of subgroups of aneuploid tumor in EAC.

The aneuploid tumors with DI ≤1.20 were mainly found in grade 1 and grade 2 tumors and were three times more prevalent than aneuploid tumors with DI >1.20 (Table 2, Figure 1). We are not aware of any DNA ploidy studies specifically investigating the importance of near-diploid aneuploid tumors. Earlier, Atkins [26], using cytogenetic analysis, reported hyperdiploid populations in EAC with an additional chromosome and considered those prognostically favorable. We found that a minor DNA content deviation (DI ≤1.20) indicated a significantly higher risk for recurrence compared with the patients with diploid tumors, whereas the PFS and OS were not significantly different. Additionally, these tumors relapse mainly in the vagina and pelvis similar to diploid tumors. This might indicate that patients with aneuploid tumor with DI ≤1.20 can be followed up or be considered for vaginal brachytherapy. In a study by Mangili et al. [9], the patients with aneuploid tumor with DI ≤1.20 were grouped along with the patients with diploid tumor in order to take a decision regarding adjuvant therapy.

In contrast to the aneuploid tumors with DI ≤1.20, the aneuploid tumors with DI >1.20 were clinically aggressive and relapsed mainly outside pelvis similar to serous and clear-cell adenocarcinomas [27, 28], indicating that these patients can be potential candidates for chemotherapy. The incidence of tumors with DI >1.20 was found to be higher in grade 3 tumors than in grade 1 and 2 tumors (Table 3). The patients had significantly poorer PFS and OS than the patients with diploid tumor. Similar to our result, Mariani et al. [19] reported that DI >1.50 was a predictor for distant failure. However, they grouped diploid tumors and aneuploid tumors with DI <1.50 into one group and aneuploid tumor with DI >1.50 and tetraploid into another group.

In EAC, there is no data in the existing literature on the prognostic importance of tetraploidy since these tumors either were included in diploid [12] or in the aneuploid group [14]. In this series, we found a significant number of tetraploid tumors (52 cases, 5.4%) and the recurrence rate for these patients was slightly higher compared with the patients with diploid tumor. The PFS and OS of the patients with tetraploid tumor were intermediate between the patients with diploid and aneuploid tumors (Table 2, Figure 2), findings similar to ovarian carcinomas [29]. Furthermore, the patients with recurrent tetraploid tumor had worse OS compared with the patients with other recurrent tumors in this series.

Initially, we believed that the DNA ploidy results from hysterectomy and curettage specimens were interchangeable. Subsequently, after terminating the study, we found that the DNA ploidy results differed in the specimens in approximately one-fourth of the cases [30]. We found that DNA ploidy results from hysterectomy specimen provided better prognostic information compared with curettage specimen. This finding is also supported by the results in a relatively large series by Baak et al. [12]; however, other investigators reported that curettage specimen was useful for prognostication as well [31, 32]. The possible explanation might be that the biology of the deep infiltrating part of a tumor, which is best represented in hysterectomy specimen, plays a more important role in recurrence than the superficial part of the tumor obtained in curettage specimen [12]. Therefore, we believe that whenever possible, hysterectomy specimen should be used for DNA ploidy analysis.

In multivariate analysis in endometrial carcinoma, DNA ploidy has been reported as a prognostic marker by many investigators [3, 4, 11, 14]. However, multivariate analyses were carried out in a limited number of cases and events [33], using dichotomized DNA ploidy with dissimilar criteria for classification [3, 9, 17], and incorporating usually aneuploid type 2 carcinoma [3, 11]. Therefore, it is difficult to draw a conclusion on the prognostic superiority DNA ploidy over the traditional prognostic markers in the existing literature. In our series, only traditional prognostic markers retained statistical significance in multivariate analysis (Table 4). Therefore, DNA ploidy results along with other established parameters have to be taken in consideration for prognostication of the patients with endometrial carcinoma.

Most of the reported works on DNA ploidy were carried out by flow cytometry [5, 7, 8, 12–14], although image cytometry was found to be better in finding aneuploid subpopulations than flow cytometry [34]. Image cytometry enables discarding cut nuclei and duplets from the analysis and nuclei can be grouped in different galleries so that reference cells do not interfere in DNA ploidy analysis resulting in a more accurate result. Furthermore, the reproducibilities of the DNA ploidy diagnoses and DI were found to be very good (κ = 0.89). We additionally studied the prognostic importance of other DNA ploidy parameters, namely, S-phase and 5c ER. They did not add any further information than DNA ploidy and DI (data not shown).

In conclusion, DI of the aneuploid tumor has to be taken into consideration in DNA ploidy results as the two subgroups had different recurrence pattern and survivals. The patients with aneuploid tumor with DI >1.20 had higher recurrence rate, higher distant failure rate and poorer PFS and OS. The patients with aneuploid tumors with DI ≤1.20 relapsed mainly locally and had higher recurrence rate than the patients with diploid tumor. These findings suggest that extent of gross genomic aberration influences on cancer progression, implying further research.

funding

This work was supported by Radiumhospitalets Legater.

disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Signe Eastgate and Erika Thorbjørnsen for their technical assistance in DNA ploidy analyses. Special thanks to Odd Røyne, Yunyong Wang and Wanja Kildal, PhD for database management, clinical data entry and suggestions on the manuscript, respectively.

References

- 1.Prat J. Prognostic parameters of endometrial carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:649–662. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeler VM, Kjørstad KE. Endometrial adenocarcinoma in Norway. A study of a total population. Cancer. 1991;67:3093–3103. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910615)67:12<3093::aid-cncr2820671226>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundgren C, Auer G, Frankendal B, et al. Prognostic factors in surgical stage I endometrial carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:49–56. doi: 10.1080/02841860310018990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvesen HB, Akslen LA. Molecular pathogenesis and prognostic factors in endometrial carcinoma. APMIS. 2002;110:673–689. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.1101001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susini T, Amunni G, Molino C, et al. Ten-year results of a prospective study on the prognostic role of ploidy in endometrial carcinoma: DNA aneuploidy identifies high-risk cases among the so-called ‘low-risk’ patients with well and moderately differentiated tumors. Cancer. 2007;109:882–890. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terada K, Mattson D, Goo D, Shimizu D. DNA aneuploidy is associated with increased mortality for stage I endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wik E, Trovik J, Iversen OE, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy in endometrial carcinoma: a reproducible and valid prognostic marker in a routine diagnostic setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindahl B, Masback A, Persson J, et al. Adenocarcinoma corpus uteri stage I-II: results of a treatment programme based upon cytometry. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4731–4735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangili G, Montoli S, De Marzi P, et al. The role of DNA ploidy in postoperative management of stage I endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1278–1283. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Högberg T, Fredstorp-Lidebring M, Alm P, et al. A prospective population-based management program including primary surgery and postoperative risk assessment by means of DNA ploidy and histopathology. Adjuvant radiotherapy is not necessary for the majority of patients with FIGO stage I-II endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:437–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaino RJ, Davis AT, Ohlsson-Wilhelm BM, Brunetto VL. DNA content is an independent prognostic indicator in endometrial adenocarcinoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17:312–319. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baak JP, Snijders W, van Diermen B, et al. Prospective multicenter validation confirms the prognostic superiority of the endometrial carcinoma prognostic index in international Federation of gynecology and obstetrics stage 1 and 2 endometrial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4214–4221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordström B, Strang P, Lindgren A, et al. Carcinoma of the endometrium: do the nuclear grade and DNA ploidy provide more prognostic information than do the FIGO and WHO classifications? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996;15:191–201. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santala M, Talvensaari-Mattila A. DNA ploidy is an independent prognostic indicator of overall survival in stage I endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:5191–5196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg SG, Kurman RJ, Nogales F, et al. Tumours of uterine corpus. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2003. pp. 218–232. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorbe B, Risberg B. Prognostic importance of the nuclear proteins p53 and Rb in conjunction with DNA, nuclear morphometry and grading in endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:34–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1997.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ørbo A, Rydningen M, Straume B, Lysne S. Significance of morphometric, DNA cytometric features, and other prognostic markers on survival of endometrial cancer patients in northern Norway. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:49–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pradhan M, Abeler VM, Danielsen HE, et al. Image cytometry DNA ploidy correlates with histological subtypes in endometrial carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariani A, Sebo TJ, Webb MJ, et al. Molecular and histopathologic predictors of distant failure in endometrial cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim P, Aquino-Parsons CF, Wong F, et al. Low-risk endometrial carcinoma: assessment of a treatment policy based on tumor ploidy and identification of additional prognostic indicators. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:191–195. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundgren C, Auer G, Frankendal B, et al. Nuclear DNA content, proliferative activity, and p53 expression related to clinical and histopathologic features in endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:110–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lax SF. Molecular genetic pathways in various types of endometrial carcinoma: from a phenotypical to a molecular-based classification. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 6th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S105–S143. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abeler VM, Kjørstad KE. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: a histopathological and clinical study of 97 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:207–217. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90279-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abeler VM, Kjørstad KE, Berle E. Carcinoma of the endometrium in Norway: a histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1992;2:9–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1992.02010009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkin NB. Frequency of hyperdiploid chromosome complements in endometrioid tumors of the endometrium whereas similar tumors in the ovary tend to show hypodiploidy: a significant difference that may not be distinguishable by flow cytometry of DNA content. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;97:39–42. doi: 10.1159/000064053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abeler VM, Vergote IB, Kjørstad KE, Tropé CG. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium. Prognosis and metastatic pattern. Cancer. 1996;78:1740–1747. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961015)78:8<1740::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benito V, Lubrano A, Arencibia O, et al. Pure papillary serous tumors of the endometrium: a clinicopathological analysis of 61 cases from a single institution. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1364–1369. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b7a1d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristensen GB, Kildal W, Abeler VM, et al. Large-scale genomic instability predicts long-term outcome for women with invasive stage I ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1494–1500. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pradhan M, Abeler VM, Davidson B, et al. DNA ploidy heterogeneity in endometrial carcinoma: comparison between curettage and hysterectomy specimens. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:572–578. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181e2e8ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Susini T, Rapi S, Massi D, et al. Preoperative evaluation of tumor ploidy in endometrial carcinoma: an accurate tool to identify patients at risk for extrauterine disease and recurrence. Cancer. 1999;86:1005–1012. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990915)86:6<1005::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podratz KC, Wilson TO, Gaffey TA, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis facilitates the pretreatment identification of high-risk endometrial cancer patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodama S, Kase H, Tanaka K, Matsui K. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in patients with endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;53:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kærn J, Wetteland J, Tropé CG, et al. Comparison between flow cytometry and image cytometry in ploidy distribution assessments in gynecologic cancer. Cytometry. 1992;13:314–321. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]