Abstract

The presence of metaplastic ossification within atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma (ALT/WDLPS) is a rare occurrence. When present, bone formation is most often found in association with a dedifferentiated component arising within the primary tumor. It is important for the radiologist not only to recognize the differential diagnosis of a calcified or ossified soft tissue mass but also be aware of the various soft tissue neoplasms, both aggressive and non-aggressive, that may show such features. We report a case of ALT/WDLPS with unusual extensive metaplastic bone formation without an element of dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

Keywords: Atypical lipomatous tumor, well-differentiated liposarcoma, metaplastic ossification

Introduction

Metaplastic ossification within atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma (ALT/WDLPS) is a rare occurrence[1], and when present is often associated with a dedifferentiated component[2–4]. We report the radiologic and pathologic features of a rare case of ALT/WDLPS with extensive metaplastic ossification, however without an element of dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS).

Case report

A 67-year-old Caucasian man presented with bilateral shoulder pain. Radiographs indeed revealed bilateral symmetric degenerative disease. However, a large densely calcified mass was incidentally seen in the soft tissues overlying the right scapula (Fig. 1). The patient was unaware of the mass and denied trauma to the site, focal or asymmetric pain, weight loss, other constitutional symptoms, or known history of malignancy. The possibilities of heterotopic ossification, myositis ossificans, tumoral calcinosis, and soft tissue sarcoma were raised; the patient was thus referred for further clinical and radiographic evaluation.

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the right shoulder shows a large mass with extensive calcific density (arrow) overlying the right scapula.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, technetium-99 m-methylene diphosphonate [99mTc]MDP) bone scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed. CT scan demonstrated a large 13 × 8 × 5 cm well-circumscribed mass with a thin capsule medially located in the right posterior shoulder, superficial to the scapula. Centrally the mass revealed dense, cloud-like calcification, which made up the bulk of the lesion. This was surrounded by a rim of mostly simple appearing fat. Associated thinning and irregularity of the underlying scapula were present, and were thought to be due to pressure erosion (Fig. 2). [99mTc]MDP bone scan demonstrated a large amount of activity associated with the primary mass. An additional focus of tracer accumulation in the right posterior seventh rib corresponded to a remote, healing rib fracture (Fig. 3). MRI demonstrated a large, lobulated, circumscribed mass adjacent to the rotator cuff musculature, displacing the infraspinatous and teres minor. A large central area of hypointensity on both T1 and T2 sequences corresponded to areas of dense calcification seen on radiograph and CT. A surrounding rim of fatty tissue showed minimal internal septation and hyperintense signal on T1-weighted imaging (Fig. 4A). Post-contrast T1 fat-saturated images revealed thin linear areas of enhancement traversing both the calcified and fatty component (Fig. 4B), with suppression of hyperintense signal of the fatty component.

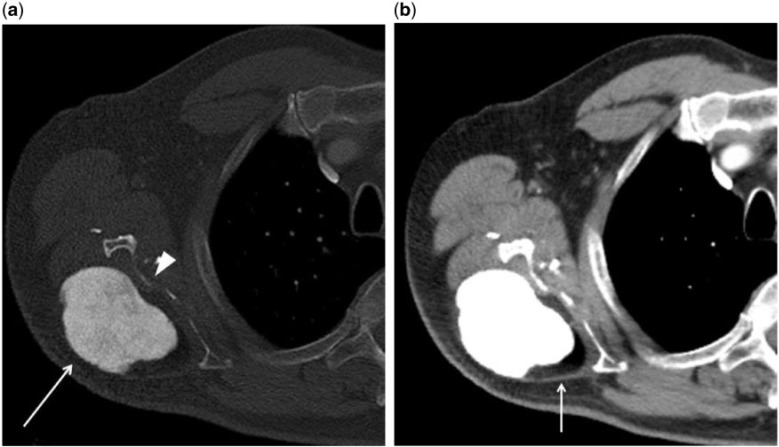

Figure 2.

Axial CT scan of the right shoulder in (a) bone and (b) soft tissue windows reveals the mass in question. The bone window reveals a central cloud-like area of high density, consistent with ossification (arrow). Thinning and irregularity of the adjacent scapula, likely secondary to chronic pressure erosion (arrow head) is also present. The soft tissue window reveals to advantage the encapsulated fatty component at the periphery of the mass (arrow).

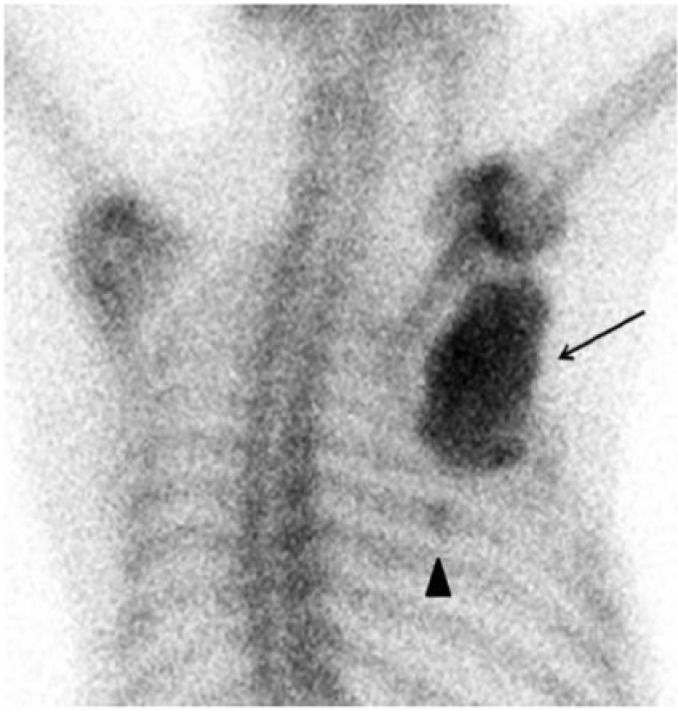

Figure 3.

Posterior view from a [99mTc]MDP bone scan reveals intense tracer accumulation within the primary tumor, most intensely in the central area of ossification (arrow). A remote, healing seventh rib fracture was seen incidentally (arrow head).

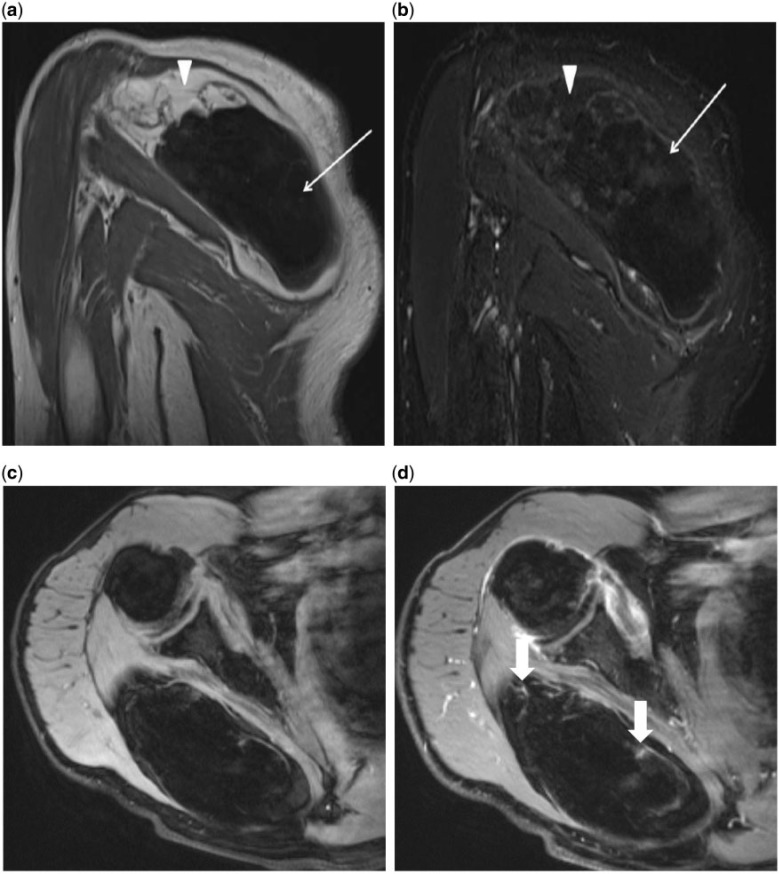

Figure 4.

(A) Oblique coronal T1-weighted MRI of the right shoulder reveals a large mass overlying the right scapula and displacing the infraspinatous and teres minor. The central area of signal dropout corresponds to the ossified portion of the mass (arrow), and the surrounding area of hyperintensity is consistent with fat (arrowhead). (b) Oblique coronal post-contrast T1-weighted MRI with fat saturation demonstrates the area of signal drop out within the tumor corresponding to fat (arrowhead). Minimal linear enhancement extending throughout the mass and faint enhancement of the central ossified portion (arrow) is seen. (c) Axial pre-contrast T1-weighted MRI with fat saturation. (d) Axial post-contrast T1-weighted MRI with fat saturation demonstrates minimal linear enhancement extending throughout the mass and faint enhancement of the central ossified portion (arrows).

Based on the imaging, the differential diagnosis for the mass included both benign and malignant entities. Benign entities included metastatic calcification, benign lipoma with calcified fat necrosis, variants of benign lipoma such as osteolipoma and chondrolipoma, parosteal lipoma, and myositis ossificans; malignant entities included extraskeletal osteosarcoma and liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation.

The patient was subsequently referred for percutaneous biopsy, and samples of both the calcified and non-calcified portions of the mass were obtained. CT-guided core-needle biopsy of the right upper back mass was performed using a 13.5-gauge introducer, an 18-gauge × 15-cm Temno biopsy needle and lateral to medial approach. Four core biopsies were obtained through the soft tissue component of the mass; a single core was obtained through the calcified portion of the mass using a bonopty drill advanced though the introducer. Tumor seeding along a needle path is sufficiently rare as not to be an issue in clinical practice for sarcomas.

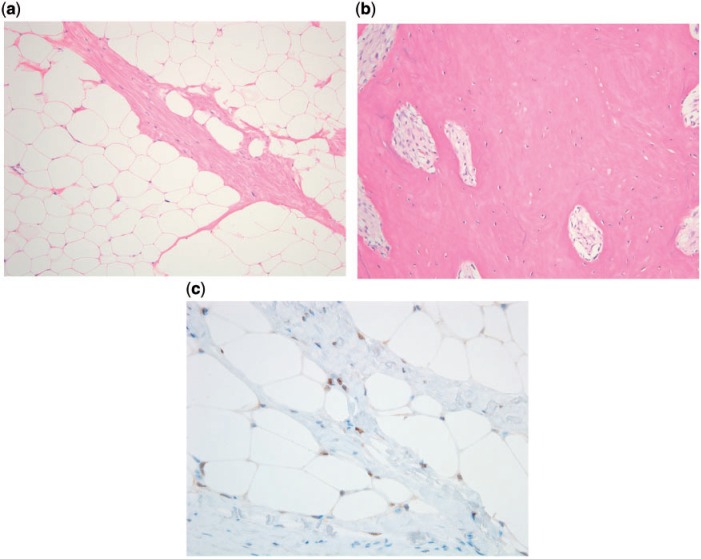

Histologically, the peripheral, non-calcified portion of the mass consisted of adipose tissue with slight variation in adipocyte size and occasional hyperchromatic stromal cells that were focally positive for MDM2 and CDK4 by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5). Cytogenetic analysis showed ring chromosomes. These features are characteristic of atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT). ALT/WDLPS contains ring and giant marker chromosomes composed of amplified material from the long arm of chromosome 12 (12q13–15), which leads to overexpression of both MDM2 and CDK4[2]. Immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can therefore be used to confirm the diagnosis[2,5,6], because benign lipomatous tumors do not harbor these genetic abnormalities. The central portion of the mass revealed devitalized bony fragments.

Figure 5.

Histology of atypical lipomatous tumor with extensive ossification. (a) Non-ossified adipocytic component showing slight variation in adipocyte size, thickened fibrous septum, and occasional hyperchromatic cells. (b) The dominant ossified component was composed of mature trabecular bone. (c) Immunohistochemical staining for MDM2 showed positive nuclear staining, confirming the diagnosis.

With the diagnosis of ALT, the patient went on to full surgical excision for definitive treatment. The lesion was easily excised from the surrounding soft tissues, and no bony invasion was seen intra-operatively. Gross examination revealed a mass that was over 95% ossified, with the remainder being composed of lobulated adipose tissue. The histologic diagnosis of ALT with extensive metaplastic ossification was made. No dedifferentiated component was identified. No adjuvant therapy was recommended, although due to the unusual finding of metaplastic ossification, the patient was closely followed clinically and radiographically. Approximately 3 years after resection, the patient remains without evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Discussion

Lipogenic tumors, both benign and malignant, are common entities that have been reported throughout the body[5,7,8], accounting for nearly 50% of soft tissue neoplasms clinically encountered[8]. Liposarcoma (LPS) accounts for approximately 25% of all sarcomas presenting in adults[5].

Both benign and malignant lipogenic tumors have varying radiologic presentations with significant overlap in appearance; final diagnosis is often made by genetic and histologic analysis. For example, in a study by Gaskin and Helms[9] in which 126 consecutive fatty masses were evaluated by MRI, the positive predictive value was only 38% when the diagnosis of well-differentiated LPS was suggested, with final pathologic diagnosis often being that of simple lipoma or a benign lipoma variant.

Similarly, the presence of calcification or ossification within an adipocytic lesion can be a diagnostic dilemma for the radiologist. Benign entities such as lipoma should be considered, as trauma or ischemia can lead to central fat necrosis and subsequent calcification[7], although the extent of ossification and homogeneity seen in our case would be atypical. Myositis ossificans in the late stages (more than 6 months) presents as a densely ossified mass and can therefore appear similar, particularly on radiographs, although the presence of fat as in this case would be unusual. History of trauma and various stages of maturation of myositis ossificans on imaging are important differentiating features[10]. Moreover, zonal pattern of ossification toward the periphery on histology is a characteristic feature. Other rare, benign lipoma variants including chondrolipoma and osteolipoma can have grossly visible metaplastic bone formation[11,12]. Chondrolipoma, furthermore, has a propensity to present in the proximal extremities and limb girdles[11]. Parosteal lipoma, a benign lipoma adherent to the underlying bone, was a consideration in our case, as the scapula is a common location for this lesion and the mass itself can cause reactive changes in the associated bone[13].

Malignant tumors should always be considered in the differential for adipocytic masses with calcification or ossification. For example, rarely, metaplastic bone formation can be seen associated with well-differentiated LPS[1], and DDLPS not uncommonly shows metaplastic bone formation and heterologous elements, including osteosarcomatous differentiation[3,14–16]. Ossification in the soft tissues without surrounding fatty tissue should also raise concern for extraskeletal osteosarcoma.

The nomenclature used to describe the tumor in our case warrants particular attention. The term atypical lipomatous tumor and well-differentiated liposarcoma are indeed two names for the same entity. Histologically and genetically, the tumors are identical, consisting of well-differentiated adipocytic tissue with sometimes subtle histologic differences from benign lipoma (including variation in adipocyte size, thickened fibrous septa, and atypical hyperchromatic stromal cells) and ring or giant marker chromosomes containing amplified material from the long arm of chromosome 12 (12q13–15), resulting in MDM2 and CDK4 overexpression in most cases[5]. Subtypes of benign lipomatous lesion are initially distinguished from well-differentiated liposarcoma by the image-guided percutaneous core-needle biopsies. FISH for MDM2 performed on core-needle biopsy material is reported to be more sensitive and specific than immunohistochemistry for well-differentiated liposarcoma; however, FISH and immunohistochemistry have similar results on resection specimens[17].The behavior of the tumors, furthermore, is the same in that they have no metastatic potential. The World Health Organization refers to these tumors as a single entity[18]. The true distinction, therefore, is solely anatomic, with tumors presenting in the extremities and subcutaneous tissues being labeled as ALT and tumors in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, mesentery, spermatic cord, or other locations being labeled as WDLPS. The distinction in terminology, however, does carry differing connotations. This developed from the idea that tumors presenting in the extremities or superficial tissues, the so-called atypical lipomatous tumors, have higher rates of complete surgical excision, lower rates of local recurrence, and lower risk of undergoing dedifferentiation compared with tumors arising in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, or spermatic cord; hence the term well-differentiated liposarcoma[3,5,8,9].

The entities of ALT/WDLPS and DDLPS are often considered together due to their common genetic alterations, with the distinction of DDLPS based on the histologic finding of a non-lipogenic component[3,5]. The histologic appearances of DDLPS vary greatly, ranging from a relatively uniform spindle cell morphology to a highly pleomorphic undifferentiated appearance. Certain patterns, including a meningothelial-like whorling pattern of dedifferentiation, have been recently linked to bone formation within DDLPS in some cases[1,3,4,14–16]. Our case is rare in that it demonstrates extensive metaplastic ossification within an ALT/WDLPS not associated with meningothelial-like, osteosarcomatous, or other types of dedifferentiated tissue.

Conclusion

Although a rare entity, ALT/WDLPS with metaplastic ossification should be considered in the differential diagnosis for a calcified soft tissue mass. Although our case represents an instance when no dedifferentiation was seen, it is important to be aware that metaplastic bone formation is often associated with tumors harboring a dedifferentiated component. Proper diagnosis is essential for optimal surgical planning and possible subsequent treatment.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Gupta R, Sharma A, Arora R, Kulkarni MP, Chattopadhaya TK, Singh MK. Well differentiated mesenteric liposarcoma with osseous metaplasia: a potential diagnostic dilemma for the pathologist. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41:79–83. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thway K, Robertson D, Thway Y, Fisher C. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma with meningothelial-like whorls, metaplastic bone formation, and CDK4, MDM2, and p16 expression: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:356–63. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820832c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nascimento AG, Kurtin PJ, Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a report of nine cases with a peculiar neural like whorling pattern associated with metaplastic bone formation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:945–55. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song JS, Gardner JM, Tarrant WP, et al. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma with peculiar meningothelial-like whorling and metaplastic bone formation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coindre JM, Pédeutour F, Aurias A. Well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:167–79. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binh MB, Sastre-Garau X, Guillou L, et al. MDM2 and CDK4 immunostainings are useful adjuncts in diagnosing well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma subtypes: a comparative analysis of 559 soft tissue neoplasms with genetic data. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1340–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000170343.09562.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JY, Park JM, Lim GY, Chun KA, Park YH, Yoo JY. Atypical benign lipomatous tumors in the soft tissue: radiographic and pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:1063–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200211000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kooby DA, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF, Singer S. Atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma of the extremity and trunk wall: importance of histological subtype with treatment recommendations. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:78–84. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaskin CM, Helms CA. Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:733–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy EF, Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:609–19. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch B, Hermann G, Klein MJ, Abdelwahab IF. Ossifying chondroid lipoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:475–80. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heffernan EJ, Lefaivre K, Munk PL, Nielsen TO, Masri BA. Ossifying lipoma of the thigh. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e207–10. doi: 10.1259/bjr/38805072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das P, Safaya R. Ossifying parosteal lipoma of shoulder: diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:312–13. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.41711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M. Liposarcoma with meningothelial-like whorls: a study of 17 cases of a distinctive histological pattern associated with dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:414–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macarenco RS, Erickson-Johnson M, Wang X, Jenkins RB, Nascimento AG, Oliveira AM. Cytogenetic and molecular genetic findings in dedifferentiated liposarcoma with neural-like whorling pattern and metaplastic bone formation. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;171:126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toms AP, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS. Low-grade liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous dedifferentiation: radiological and histological features. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:286–9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver J, Rao P, Goldblum JR, et al. Can MDM2 analytical tests performed on core needle biopsy be relied upon to diagnose well-differentiated liposarcoma? Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1301–6. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. IARC. 2002:227–32. [Google Scholar]