Abstract

Background

Smoking prevalence among persons in addiction treatment is 3–4 times higher than in the general population. However, treatment programs often report organizational barriers to providing tobacco-related services. This study assessed the effectiveness of a six month organizational change intervention, Addressing Tobacco Through Organizational Change (ATTOC), to improve how programs address tobacco dependence.

Methods

The ATTOC intervention, implemented in three residential treatment programs, included consultation, staff training, policy development, leadership support and access to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) medication. Program staff and clients were surveyed at pre- and post-intervention, and at 6 month follow-up. The staff survey measured knowledge of the hazards of smoking, attitudes about and barriers to treating smoking, counselor self-efficacy in providing such services, and practices used to address tobacco. The client survey measured knowledge, attitudes, and tobacco-related services received. NRT use was tracked.

Results

From pre- to post-intervention, staff beliefs became more favorable toward treating tobacco dependence (F(1, 163) = 7.15, p = 0.008), NRT use increased, and tobacco-related practices increased in a non-significant trend (F(1, 123) = 3.66, p = 0.058). Client attitudes toward treating tobacco dependence became more favorable (F(1, 235) = 10.58, p = 0.0013) and clients received more tobacco-related services from their program (F(1, 235) = 92.86, p < 0.0001) and from their counselors (F(1, 235) = 61.59, p < 0.0001). Most changes remained at follow-up.

Conclusions

The ATTOC intervention can help shift the treatment system culture and increase tobacco services in addiction treatment programs.

Keywords: Drug abuse treatment, Addiction, Smoking, Tobacco dependence

1. Introduction

While tobacco use claims 5 million lives annually worldwide, tobacco control efforts in the United States have reduced smoking prevalence from 40% in 1964 to 20.6% currently (World Health Organization, 2010; Department of Health Education and Welfare, 1964; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Schroeder and Warner (2010) admonish us not to forget tobacco’s continued toll on persons with mental health and substance use disorders, who consume 44% of all cigarettes in the U.S. (Lasser et al., 2000). Individuals with substance addiction are heavy smokers (Kozlowski et al., 1986; Hughes, 1996, 2002; Marks et al., 1997; Hays et al., 1999; Sobell, 2002), have limited success in quit attempts (Bobo et al., 1987; Kozlowski et al., 1989; Zimmerman et al., 1990; Joseph et al., 1993; Drobes, 2002; Sobell, 2002), and more often die from smoking-related causes than from other drug or alcohol-related causes (Hser et al., 1994; Hurt et al., 1996). In addiction treatment settings, client smoking prevalence ranges from 47% to 94% (Guydish et al., 2011).

The recommendation that addiction treatment programs should address tobacco, seen in the literature over 30 years (Hoffman and Slade, 1993; Currie et al., 2003; Stuyt et al., 2003; Olsen et al., 2005; Richter and Arnsten, 2006; Schroeder and Morris, 2010), is now codified in clinical guidelines (Fiore et al., 2008) and position statements (American Public Health Association, 2003; American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2008; NAADAC, n.d.). One longitudinal study found that self-reported smoking cessation during the first year after admission to addiction treatment was associated with improved alcohol and drug use outcomes (Tsoh et al., 2010). Despite these changes, three studies have concluded that tobacco dependence services are not provided in most addiction treatment programs (Richter et al., 2004; Fuller et al., 2007; Friedmann et al., 2008). Rothrauff and Eby (2010) attributed low adoption of tobacco cessation medications to historical program paradigms (e.g., 12-Step), among other factors. Knudsen and colleagues found that attitudes toward smoking cessation programs, type of facility (e.g., medical-based) and availability of resources affect the adoption of smoking cessation in addiction treatment (Knudsen, 2009; Knudsen et al., 2010). Other barriers include limitations on staff time and training, lack of reimbursement for tobacco services, the cost of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and elevated rates of staff smoking in some programs (Guydish et al., 2007). Staff resistance (Hurt et al., 1995; Hahn et al., 1999) is rooted in the belief that patients should avoid major life changes (including smoking cessation) early in recovery (Sees and Clark, 1993; Sussman, 2002). However, treating tobacco dependence does not jeopardize recovery from other drug use (Toneatto et al., 1995; Martin et al., 1997; Stuyt, 1997; Prochaska et al., 2004).

Observers have noted the systemic nature of these barriers, and suggested that organizational change is needed. For example, Campbell et al. (1995, p. 93) recommended “transforming the institutional culture so that it supports rather than conflicts with the goal of smoking cessation.”

Early investigators who tried to change this culture include Hoffman and Slade, who developed an organizational intervention described in Drug Free is Nicotine Free (Hoffman et al., 1997). Ziedonis and colleagues modified and expanded the organizational change components of Hoffman and Slade’s guidelines into the current Addressing Tobacco Through Organizational Change (ATTOC) intervention (Ziedonis et al., 2007; University of Massachusetts Medical School and Department of Psychiatry, n.d.). ATTOC has three phases and ten steps, and includes training on motivation based treatment approaches, links to quit lines and community services, use of communication planning, developing standard operating procedures, using performance improvement strategies, and assessment of agency strengths and weaknesses.

Sharp et al. (2003) reported on 3 programs that incorporated tobacco dependence treatment using an ATTOC-like approach (Slade and Hoffman, 1992; Hoffman et al., 1997) and contrasted this with failed attempts to integrate tobacco dependence without an organizational change model (Rustin, 1998). Similarly, a one-year retrospective evaluation of an ATTOC-like intervention in 30 New Jersey residential programs found that all programs provided more tobacco dependence treatment, half had adopted smoke-free grounds, and 41% of smokers did not smoke during their residential stay (Williams et al., 2005). To date, however, there are no published reports of rigorous prospective investigation concerning staff and client impacts of the manualized ATTOC intervention.

This study tested the ATTOC intervention in three agencies with residential treatment programs located in Massachusetts, Ohio and Oregon. In a multiple baseline design with each agency as its own control, the agencies participated in a 6 month ATTOC intervention that was designed to support staff-level change in tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes and practices, and increase client exposure to tobacco dependence intervention. Study hypotheses predicted improvement in: (1) staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning tobacco; (2) client knowledge, attitudes, and tobacco-related services received, and (3) utilization of NRT medication.

2. Methods

2.1. The ATTOC intervention

With consultation from the University of Massachusetts ATTOC Intervention Team, each agency identified an on-site Tobacco Champion, Tobacco Counselors, and a Leadership Team. During the first month of the intervention, the consult team visited each agency to conduct a detailed assessment (e.g., smoking on the campus, tobacco signage, review of client medical records and tobacco policies), and to meet with agency leaders, staff and patients. During the visit, agency leadership were trained on the ATTOC model, including performance improvement strategies, and all clinical staff received 8 h of basic training on tobacco assessment and treatment. Each agency developed broad patient, staff, and environment goals, written implementation plans, and workgroups to support implementation. Examples of program goals include starting new treatment services, improved medical records documentation, and new policies and procedures to support sustainability (Stuyt et al., 2003). Following the site visit two to three staff were identified as Tobacco Counselors, and received an additional 3-day off-site advanced tobacco training. Champions and Tobacco Counselors received at least weekly phone/email consultation to continue motivation and address problems. Monthly phone meetings with the Tobacco Leadership Team supported and monitored progress. The six-month ATTOC intervention has been described elsewhere (Ziedonis et al., 2007; University of Massachusetts Medical School and Department of Psychiatry, n.d.). Finally, the study funded NRT medications ($11,000 per agency) for use by both clients and staff, for 10 months from the start of the intervention. This means that NRT was available during the 6-month intervention period, and for an additional 4 months after the intervention ended. Our interest was that NRT could support organizational change during the intervention, and also sustain changes in the post-intervention period. Agencies purchased, managed, and monitored use of NRT.

2.2. Study design

For each agency, there were three measurements: at pre-intervention, at post-intervention (6 months after the pre-measure), and at follow-up (6 months after the intervention ended). The intervention was implemented sequentially in Site 1 (October 2006–April 2007), Site 2 (August 2007–January 2008), and Site 3 (July–December 2008). Because the intervention was implemented at a later time in Sites 2 and 3, it was possible to collect an earlier wave of data in these two sites. We name this “Baseline” to distinguish it from pre-intervention data collection. These baseline data allow for consideration of any trends toward improvement before the intervention began.

2.3. Program eligibility

Only residential programs were eligible. A notice about the study was sent to all residential programs participating in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN), and 11 responded. Three were selected using these criteria: (a) program size sufficient to include 50 paid staff and to enable cross-sectional samples of 50 clients at each observation, (b) one large physical site or a number of smaller sites in close proximity, and (c) current program practice did not include tobacco assessment and intervention for clients. One selected program dropped out prior to the intervention and was replaced by a smaller program.

The participating agencies represented large multi-service addiction treatment organizations. Within each agency, only residential treatment programs were included in the study, and length of stay (LOS) in these programs varied. Site 1 included both a women’s residential program (LOS 3–4 months) and men’s residential program (LOS 2–3 months). The women’s facility used a gender responsive holistic treatment approach that promoted family systems and support as well as child safety. The treatment approach at the men’s facility was a Therapeutic Community model, with peer accountability and strict adherence to rules. The majority of clients at both facilities were mandated to treatment by court order. Site 2 included a short term mixed-gender residential program (average LOS 25 days), and a longer term women-focused program that prioritized pregnant women and women with children (LOS 4–6 months). Treatment in Site 2 was historically grounded in the Twelve-Step model of addiction and recovery, with more recent incorporation of cognitive therapy, motivational enhancement, and psychiatric services. Site 3 included two gender-specific halfway houses (LOS 3–6 months) and a mixed-gender transitional living program (LOS 28 days). In Site 3 there was a specific emphasis on return to employment and on a holistic and biopsychosocial approach to treatment.

2.4. Participants

All paid staff who worked at least 20% time were eligible. While clinical staff may have the most opportunity to influence client smoking, all staff contribute to the organizational climate. For example, clerical, janitorial, and kitchen staff may model smoking behavior, smoke together with clients on breaks, and may resist or undermine programs policies designed to address smoking.

All clients were eligible, regardless of smoking status, once they had completed at least 14 days of treatment. While smoking clients are most likely to receive tobacco-related services if available, tobacco-related knowledge and attitudes of all program clients, including non-smokers, contribute to the organizational culture related to tobacco-use.

2.5. Data collection

In each clinic a research liaison provided names of all eligible staff, and the study team prepared a survey packet (cover letter, research information sheet, survey and return envelope) for each staff member. Surveys were completed in a staff meeting arranged for that purpose. Site liaisons distributed packets to staff who were not present at the meeting, and followed up with staff as needed. The survey was brief, self-administered, and confidential. Participants received a $25 gift card or, in one site, an equivalent amount paid to the program.

To recruit clients, the liaison posted sign up sheets and screened those signing for the 14-day inclusion criteria. Thereafter, the liaison monitored new admissions and, when they met inclusion criteria, recruited them. For interested clients, the liaison arranged a phone interview research staff. The interview used verbal informed consent, and no participants declined at this stage. After the interview, the liaison provided the $20 incentive. Procedures were approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Smoking-knowledge, attitudes, and practices (S-KAP)

The staff survey, in addition to demographic and smoking variables, assessed smoking-knowledge, attitudes, and practices (S-KAP; Delucchi et al., 2009). The five S-KAP scales, each scored from 1 to 5, reflect Knowledge of the hazards of smoking (α = 0.85), Attitudes about treating smoking in addiction programs (α = 0.74), Barriers to providing tobacco treatment (α = 0.81), counselor Self-efficacy in providing tobacco-related services (α = 0.72) and Practices used to address tobacco dependence with clients (α = 0.91) (Delucchi et al., 2009). S-KAP scales previously distinguished different levels of practices in different clinics (Tajima et al., 2009), and were used to assess change when clinics participated in smoking-cessation trials (Chun et al., 2009). Two scales are calculated for all staff (Knowledge, Attitudes), while remaining scales are calculated for clinical staff only (Barriers, Self-Efficacy, Practices). Participants who identified as a clinician, counselor, assistant counselor, or case manager in their job title were classified as clinicians. Participants in other job titles (e.g., program director, administrator) were classified as clinicians if they reported more than 5 client contact hours per week or a monthly caseload greater than 5.

2.6.2. Smoking-knowledge, attitudes, and services (S-KAS)

The client S-KAS measure, similar to the staff survey, also asked about tobacco-related services the client received while in treatment (Guydish et al., 2010). The four S-KAS scales, each scored from 1 to 5, reflect Knowledge (α = 0.57), Attitudes (α = 0.75) and tobacco-related Clinician Services (α = 0.82) and Program Services (α = 0.82). One scale is calculated for all clients (Knowledge), while three are calculated for smokers only (Attitudes, Clinician Service, Program Service).

2.7. NRT log

This included recipient ID number, type of NRT (gum or patch) and date and amount provided.

2.8. Data analysis

Outcomes are the five staff S-KAP scales, the four client S-KAS scales, and NRT use. Across all 9 scales the number of items per scale ranged from 4 to 11. Scale means were calculated only when data were present for at least 75% of items in the scale. Linear mixed-effects models were tested for each scale, including effects for time, site, and their interaction. Models accounted for nesting of staff and clients within program. The staff model allowed for correlations within site and within subject, as some staff respondents were the same person at multiple waves. The client model allowed for correlations within site only. As baseline demographic differences were observed between sites, staff and client models controlled for age, gender, Hispanic ethnicity, race, and smoking status. Staff analyses controlled for being in recovery from substance abuse, and client analyses controlled for primary drug of choice.

The relevant comparisons become Baseline to Pre-intervention for two sites (to assess any pre-existing trends that may affect interpretation), pre–post-intervention for all sites (to assess intervention effects), and pre-intervention to follow-up (to assess whether pre–post changes may be sustained 6 months after the intervention ends). All data collection was completed in September 2009, and data analyses reported were completed in December 2010.

3. Results

3.1. Survey completion

Number of eligible staff, proportion completing the staff survey, and number of clients surveyed, by site and wave, are shown in Table 1. Baseline data collection occurred at Sites 2 and 3 only. Across all sites, four eligible clients declined participation. An unknown number were lost because they left the program after becoming eligible but before the phone interview.

Table 1.

Sample size and survey completion rates at baseline, pre- and post-intervention, and follow-up.

| Site | Baseline | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff, N | Staff completion rate (%) |

Client, N | Staff, N | Staff completion rate (%) |

Client, N | Staff, N | Staff completion rate (%) |

Client, N | Staff, N | Staff completion rate (%) |

Client, N | |

| Site 1a | 57 | 95 | 50 | 57 | 95 | 50 | 59 | 95 | 50 | |||

| Site 2 | 46 | 98 | 50 | 49 | 88 | 50 | 42 | 90 | 50 | 36 | 83 | 50 |

| Site 3 | 20 | 95 | 50 | 18 | 94 | 50 | 24 | 83 | 50 | 24 | 92 | 50 |

| Totalb, c | 66 | 97 | 100 | 124 | 92 | 150 | 123 | 92 | 150 | 119 | 91 | 150 |

No baseline data for Site 1.

Staff N totals show number of surveys distributed (number of staff eligible).

Staff completion Ns are as follows: baseline = 64, pre = 114, post = 113, and follow-up = 108.

3.2. Participant characteristics

Demographic characteristics for staff and clients at pre-intervention, by clinic, are shown in Table 2. For all staff combined mean age was 45.1 (SD = 11.8) and 74.6% were women. Many (42.1%) were current smokers and 64.0% were in recovery from substance abuse. For all clients mean age was 35.1 (SD = 9.9), 58.7% were women, 4.7% held a college degree, and 85.3% were current smokers. Significant site differences are noted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics for staff (n = 114) and clients (n = 150) at pre intervention, by site.

| Staff | Client | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 (n = 54) | Site 2 (n = 43) | Site 3 (n = 17) | p-Value | Site 1 (n = 50) | Site 2 (n = 50) | Site 3 (n = 50) | p-Value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.28 (11.65) | 46.29 (10.18) | 35.41 (11.43) | <0.001 | 32.82 (10.22) | 38.26 (9.36) | 34.16 (9.56) | 0.016 |

| Gender, no. (%) | 0.086 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | 17 (31.5) | 6 (14.0) | 6 (35.3) | 18 (36.0) | 10 (20.0) | 34 (68.0) | ||

| Female | 37 (68.5) | 37 (86.0) | 11 (64.7) | 32 (64.0) | 40 (80.0) | 16 (32.0) | ||

| Education, no. (%) | 0.118 | 0.188 | ||||||

| No HS/GED | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 13 (26.0) | 15 (30.0) | 8 (16.0) | ||

| HS/GED | 27 (50.0) | 13 (30.2) | 9 (52.9) | 37 (74.0) | 32 (64.0) | 38 (76.0) | ||

| Bachelor/Associate | 19 (35.2) | 21 (48.8) | 7 (41.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.0) | 4 (8.0) | ||

| Graduate degreea | 6 (11.1) | 9 (20.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) | 0.022 | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (10.0) | 0.180 |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||||||

| African Am | 3 (5.6) | 21 (48.8) | 2 (11.8) | <0.0001 | 2 (4.0) | 20 (40.0) | 1 (2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 45 (83.3) | 20 (46.5) | 11 (64.7) | <0.001 | 44 (88.0) | 26 (52.0) | 42 (84.0) | <0.0001 |

| Otherb | 5 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | 6 (12.0) | ||

| Mixed race | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | ||

| Declined | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Current smoker, no. (%) | 24 (44.4) | 16 (37.2) | 8 (47.1) | 0.699 | 43 (86.0) | 38 (76.0) | 47 (94.0) | 0.039 |

| In recovery, no. (%) | 45 (83.3) | 19 (44.2) | 9 (52.9) | <0.001 | – | – | – | |

| Clinical staff,c no. (%) | 47 (87.0) | 36 (83.7) | 14 (82.4) | 0.850 | ||||

| Primary drug of choice, no. (%) | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Alcohol | – | – | – | 14 (28.0) | 11 (22.0) | 15 (30.0) | ||

| Crack/cocaine | – | – | – | 1 (2.0) | 27 (54.0) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| Heroin/opiate | – | – | – | 3 (6.0) | 10 (20.0) | 27 (54.0) | ||

| Methamphetamine | – | – | – | 22 (44.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Otherd | – | – | – | 10 (20.0) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| Smokers | n = 24 | n = 19 | n = 9 | n = 43 | n = 38 | n = 47 | ||

| Cigarettes/day,e mean (SD) | 15.17 (5.43) | 12.53 (7.19) | 17.25 (5.97) | 0.195 | 16.02 (9.10) | 18.03 (10.02) | 20.96 (8.10) | 0.036 |

For clients, information on graduate degree not available.

Includes Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan, and Other.

Clinician staff: Participants who identified as a clinician, counselor, assistant counselor, or case manager in their job title were classified as clinicians. Participants in other job titles (e.g., program director, administrator) were classified as clinicians if they reported more than 5 client contact hours per week or a monthly caseload greater than 5.

Includes Marijuana, Methadone, other prescription drugs including opiates.

Staff survey: How many cigarettes did you smoke in the past 24 h? Client survey: On a day you smoke, how many cigarettes do you usually smoke?

3.3. Use of NRT

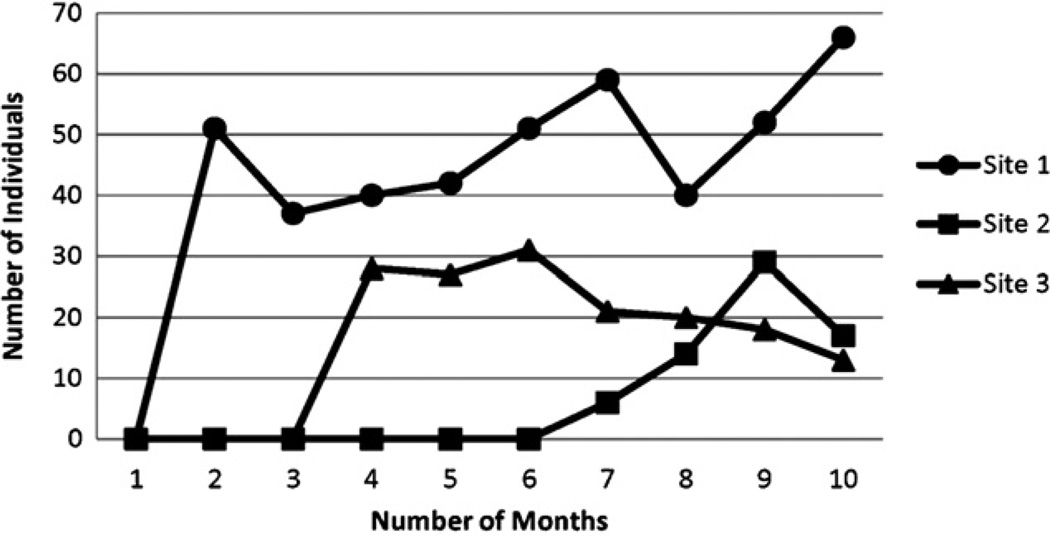

Prior to the ATTOC intervention, programs did not provide NRT. Site 1 adopted NRT rapidly, providing it to 51 persons by month 2. Given the same resources, Site 2 did not provide NRT until month 7. Fig. 1 shows the number of persons receiving NRT by month and by program, but many persons received NRT for multiple months. Overall, Site 1 provided NRT to 43 staff and 123 clients, Site 2–7 staff and 37 clients, and Site 3–17 staff and 145 clients.

Fig. 1.

Number of persons receiving NRT during and post-intervention, by site. Programs provided nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to both staff and clients. A single individual may receive NRT in multiple months. Overall, Site 1 provided NRT to 43 staff and 123 clients, Site 2–7 staff and 37 clients, and Site 3–17 staff and 145 clients.

3.4. Change over time among staff

Unadjusted means for staff scales (Knowledge, Beliefs, Barriers, Efficacy, Practice) are shown, for all time points, in the upper half of Table 3. Right hand columns show main effects for time comparing baseline and pre-intervention, pre- and post-intervention, and pre-intervention and follow-up. For the period from baseline to pre-intervention, there were no interactions (data not shown), and no main effects for time. Staff smoking was unchanged (42.2% at baseline vs. 40% at pre-intervention).

Table 3.

Results of linear mixed models testing differences for time, site and time by site interaction.

| Baseline (n = 64) | Pre-intervention (n = 114) |

Post-intervention (n = 113) |

Follow-up (n = 108) |

Time (baseline to pre) | Time (pre to post) | Time (pre to follow-up) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staffa | |||||||

| Knowledge, mean (SD) | 4.05 (0.55) | 3.98 (0.59) | 4.04 (0.70) | 4.00 (0.81) | F(1, 138) = 2.82, P = 0.095 | F(1, 164) = 1.96, P = 0.163 | F(1, 171) = 0.10, P = 0.749 |

| Beliefs | 3.34 (0.52) | 3.38 (0.56) | 3.69 (0.60) | 3.60 (0.69) | F(1, 138) = 0.04, P = 0.835 | F(1, 163) = 7.15, P = 0.008 | F(1, 171) = 6.28, P = 0.013 |

| Barriers | 2.11 (0.44) | 2.07 (0.45) | 2.01 (0.58) | 2.05 (0.48) | F(1, 115) = 0.20, P = 0.659 | F(1, 126) = 0.34, P = 0.561 | F(1, 138) = 0.30, P = 0.585 |

| Efficacy | 2.98 (0.49) | 2.95 (0.42) | 3.13 (0.55) | 3.13 (0.51) | F(1, 112) = 0.00, P = 0.997 | F(1, 126) = 2.21, P = 0.140 | F(1, 137) = 3.22, P = 0.075 |

| Practice | 2.05 (0.81) | 2.36 (0.87) | 2.75 (0.92) | 2.87 (1.00) | F(1, 112) = 1.67, P = 0.199 | F(1, 123) = 3.66, P = 0.058 | F(1, 135) = 12.01, P < 0.001 |

| Baseline (n = 100) | Pre-intervention (n = 150) | Post-intervention (n = 150) | Follow-up (n = 150) | Time (baseline to pre) | Time (pre to post) | Time (pre to follow-up) | |

| Clientb | |||||||

| Knowledge | 3.82 (0.68) | 3.94 (0.54) | 4.09 (0.51) | 4.00 (0.55) | F(1, 234) = 0.61, P = 0.437 | F(1, 281) = 9.75, P = 0.002 | F(1, 283) = 2.31, P = 0.129 |

| Attitudes | 3.53 (0.83) | 3.53 (0.72) | 3.78 (0.65) | 3.68 (0.66) | F(1, 198) = 0.26, P = 0.611 | F(1, 235) = 10.58, P = 0.001 | F(1, 240) = 3.48, P = 0.063 |

| Program Services | 1.89 (0.85) | 2.29 (1.09) | 3.25 (0.88) | 2.92 (0.90) | F(1, 198) = 0.06, P = 0.803 | F(1, 235) = 92.86, P < 0.001 | F(1, 240) = 49.21, P < 0.001 |

| Clinician Services | 1.93 (0.69) | 2.12 (0.72) | 2.90 (0.92) | 2.69 (0.83) | F(1, 198) = 0.38, P = 0.539 | F(1, 235) = 61.59, P < 0.001 | F(1, 240) = 37.62, P < 0.001 |

Scale means (SD) include all staff for Knowledge and Belief scales, and clinical staff only for remaining scales. Staff analysis controlled for age, gender, Hispanic ethnicity, race, smoking status, and whether the respondent was in recovery from substance abuse.

Scale means (SD) include all clients for Knowledge and smokers only for remaining scales. Client analysis controlled for age, gender, Hispanic ethnicity, race, smoking status, and primary drug of choice.

The period from pre- to post-intervention reflects the 6 month ATTOC intervention period. There were no time by site interactions for staff measures during this period (data not shown). One main effect for time (Beliefs) was significant such that, for all clinics combined, staff beliefs became more favorable toward treating tobacco dependence. The Practice scale, reflecting use of practices by staff to address smoking, increased but did not reach significance (F(1, 123) = 3.66, p = 0.058). Staff smoking decreased non-significantly (42.1% pre vs. 33% post).

The final period, from pre-intervention to follow-up, reflects a 12-month interval encompassing the 6-month ATTOC intervention and the 6 months after the intervention had ended. There were no interactions, and main effects for Time (Table 3) show that staff Belief and Practice scales increased significantly for all clinics combined. Staff smoking remained lower at follow-up (38.9%) compared to pre-intervention (42.1%), but this was not significant.

3.5. Change over time among clients

Unadjusted means for client scales (Knowledge, Attitudes, Program and Clinician Services) are shown in the lower half of Table 3. From baseline to pre-intervention there were no interactions (data not shown), and main effects for time show no change on any measure. Client smoking was unchanged (85% at both times).

From pre- to post-intervention there were significant time by site interactions for the Program Service and Clinician Service scales, driven by steeper increases in Site 3. These are accompanied by significant site effects such that the two remaining clinics tended to start and end in generally parallel lines. Inspection of means shows that both measures increased pre–post intervention in all sites. Main effects for time (Table 3) reflect significant pre–post increases on all four client measures. There was no change in client smoking (85.3% vs. 83.3%).

From pre-intervention to follow-up there was a single interaction, for Program Services (F(2, 240) = 3.8, p = 0.0237), also because one clinic reported a sharper increase than the others. Main effects for Time (Table 3) show that client report of Program and Clinician Services increased significantly for all clinics combined. Client smoking was the same at pre and follow-up (85.3%).

4. Discussion

Findings suggest that the ATTOC intervention was effective in modifying beliefs of both staff and clients concerning the need for tobacco treatment, and in increasing practices used to address tobacco dependence. From pre to post-intervention there were significant increases in the staff Belief scale and in all four client scales, and a trend toward increased use of tobacco-related practices. Of the changes observed on six scales from pre to post, four were maintained 6 months after the intervention ended. The increased use of NRT suggests that addiction treatment programs may use NRT, if available, to address tobacco dependence.

Several issues may warrant additional discussion. First, neither staff nor client knowledge scales showed change over time. This may be due to limitations of the scales themselves, or because smokers in addiction treatment are aware of the health risks associated with smoking. High levels of knowledge were not accompanied by high levels of tobacco-related services pre-intervention, suggesting that knowledge of the risks of smoking alone is not sufficient to support tobacco-related services in these settings. Second, increased provision of tobacco services was not associated with decreased smoking among staff, although the decrease observed among staff may be significant in a larger sample. Reducing smoking among staff seems a central goal because staff smoking prevalence in this study (33–42%) was above the national prevalence of 20.6% (CDCP, 2010), and because staff who smoke are less likely to address smoking among clients (Bobo and Davis, 1993; Campbell et al., 1998).

Third, smoking prevalence was unchanged in successive cross-sectional samples of program clients. One possibility is that clients had been enrolled in treatment for too short a time, at the point of the survey, to change tobacco-related behavior. While eligibility required being enrolled in treatment for at least 14 days, clients reported being in treatment for an average of 6.1 weeks (SD = 4.58) at pre- and 7.1 weeks (SD = 5.94) at post-intervention. Another possibility is that smoking decreased even though smoking prevalence did not change. Mean cigarettes per day among clients was 18.4 (SD = 9.21) at pre and 18.2 (SD = 8.92) at post, and the mean number of times participants had quit smoking for at least 24 h in the past year was 2.7 (SD = 6.34) at pre and 2.1 (SD = 3.44) at post. None of these differences were significant. Consequently, while tobacco-related services reported by both staff and clients increased pre–post, additional study is needed to associate increased provision of tobacco-related services with client smoking outcomes. Finally, residential programs may differ from outpatient programs with regard to tobacco-related intervention. In terms of creating more favorable attitudes toward quitting smoking and increasing tobacco-related services, residential and outpatient programs may respond similarly. But differences arise concerning policy, and particularly smoke-free grounds policies. In outpatient programs, smoke-free grounds require only that patients avoid smoking during their clinic visits. In residential programs, where patients are often confined to grounds during initial stages of treatment, smoke free grounds policies translate into forced quit-smoking periods.

In the current U.S. healthcare configuration, three-fourths of all addiction treatment is provided in the public sector (Mark et al., 2007; Mechanic et al., 1995). Program licensing and regulation activities, which may or may not support tobacco intervention, are usually centralized at the state level through addiction or behavioral health Single State Agencies. The most urgent need is for further research that can encourage these agencies to address tobacco among the patients they serve, and direct them toward effective tobacco intervention strategies and policies. State treatment systems could, for example, disseminate clinical guidelines for tobacco intervention to counselors, mandate counselor continuing education on tobacco (Hahn et al., 1999), reimburse programs for tobacco-related services, or provide cessation intervention for program staff (McCool et al., 2005). Literature to guide such decisions is limited however, as few studies have investigated program-level interventions (Bernstein and Stoduto, 1999; Bobo et al., 1997; Campbell et al., 1998; Capretto, 1993; McDonald et al., 2000; Joseph et al., 1990; Joseph, 1993) and very few report outcomes of multi-site or of system-level interventions concerning tobacco in addiction treatment (Joseph et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2005).

The ATTOC intervention, as implemented in this study, involves tailored technical assistance to agencies, and the intensity of the intervention and cost of external consultation may limit its use on a wide scale. Both New Jersey and New York modified ATTOC so that a smaller dose could be applied in a broader system (Williams et al., 2005; New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, 2008). Preliminary information concerning the New York intervention suggests that it increased tobacco-related services in outpatient settings but not in residential settings during its first year (Guydish et al., submitted for publication). Consequently, further research may be directed to components of the ATTOC intervention (e.g., NRT, staff training, organizational consultation alone or in combination) that may achieve similar results with more ability to scale up to treatment systems. Finally, research may explore impacts of other change strategies such as mandating tobacco-free campuses, providing multiple-agency training, and having current staff lead tobacco-related performance improvement projects.

Limitations of this work include the small number of programs and the inclusion of residential treatment only, both limiting generalizability. Sample size for both staff and client groups is modest, and we conducted multiple comparisons without correction for Type I error. Using a p-value of 0.01, for example, would eliminate one finding currently reported as significant for staff, and would not affect client findings. As this is the first rigorous test of the ATTOC intervention reported, we applied the standard 0.05 p-value to illuminate likely relationships. At the same time, our approach specified measures and hypotheses in advance, and tested all scales rather than a selected subset. We note that the overall pattern of findings is consistent with an interpretation of change in the desired direction over time, and we note that staff reports of providing more services were accompanied by independent client reports of receiving more services in the same clinics and at the same time. Factors other than the ATTOC intervention, especially change in state or local tobacco control policies, could account for the changes observed. We did assess the possibility that outcome measures were changing during the 6 months preceding intervention in two clinics, and found no change. Discussion with site investigators did not identify regional or system factors that could account for these changes independent of the ATTOC intervention. Increased tobacco-related services at these agencies did not reduce client smoking rates, and other research is needed to explore this question. Lastly, NRT availability was continued in this study for 4 months after the intervention ended, and this may have supported other changes sustained at follow-up. Further assessment of sustainability either in the absence of continued NRT, or over a period longer than 6 months post-intervention, would require long-term monitoring of change at the agencies. There is a potential that ATTOC effects could reverse with lack of NRT funding or lack of policy supports. The New Jersey ATTOC-like intervention was initially effective but gains were lost due to lack of enforcement (Williams et al., 2005).

In 2008, 2.3 million persons received addiction treatment in specialty clinics (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009), and most of those persons smoked (Guydish et al., 2011). Addiction treatment systems in several states have begun addressing (New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, 2008; Toussaint et al., 2009), or have committed to address (Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, n.d.) tobacco dependence. Study findings suggest that the ATTOC intervention can be effective in bringing increased tobacco services to addiction treatment populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank other members of the UMass ATTOC team: David Kalman, Sun Kim, Joseph DiFranza, Andrew Tapper, Fernando de Torrijos, Susan Hills, and Sarah Baker as well as acknowledge the excellent contributions by Greg Seward and Mia Zimmerman (of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey).

Role of funding source

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA020705), by the Western States research node of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (U10 DA015815), by the NIDA San Francisco Treatment Research Center (P50 DA009253), and by a NIDA 1K23 DA021512 to Dr. Brigham. These NIH agencies had no role in the project beyond financial support.

Footnotes

Contributors

Dr. Guydish, PI, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Barbara Tajima and Emma Passalacqua managed all staff data collection and conducted client phone interviews. Kevin Delucchi planned and Mable Chan executed data analysis and participated in interpretation of findings. Douglas Ziedonis led the ATTOC intervention team at all three participating clinic sites, Greg Seward assisted in this implementation, and Monika Kolodziej participated in manual development and intervention description. Lucy Zammarelli, Michael Levy and Greg Brigham were the site investigators, with oversight for research and intervention activities in their respective clinics.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- American Public Health Association. 2003–10 smoking cessation within substance abuse and/or mental health treatment settings. Association News 2003 Policy Statements. 2003:19–20.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Chevy Chase, MD: ASAM; 2008. Public Policy Statement on Nicotine Addiction and Tobacco (Formerly Nicotine Dependence and Tobacco) [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein SM, Stoduto G. Adding a choice-based program for tobacco smoking to an abstinence-based addiction treatment program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1999;17:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Anderson JR, Bowman A. Training chemical dependency counselors to treat nicotine dependence. Addict. Behav. 1997;22:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Davis CM. Recovering staff and smoking in chemical dependency programs in rural Nebraska. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Gilchrist LD, Schilling RF, Noach B, Schinke SP. Cigarette smoking cessation attempts by recovering alcoholics. Addict. Behav. 1987;12:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Krumenacker J, Stark MJ. Smoking cessation for clients in chemical dependence treatment. A demonstration project. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1998;15:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Wander N, Stark MJ, Holbert T. Treating cigarette smoking in drug abusing clients. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1995;12:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00002-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capretto NA. Confronting nicotine dependency at the Gateway Rehabilitation Center. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation—United States, 2008. MMWR. 2009;58:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Guydish JR, Delucchi K. Does the presence of a smoking cessation clinical trial affect staff practices related to smoking? J. Drug Issues. 2009;39:1. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie SR, Nesbitt K, Wood C, Lawson A. Survey of smoking cessation services in Canadian addiction programs. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2003;24:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Tajima B, Guydish J. Development of the Smoking Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (S-KAP) instrument. J. Drug Issues. 2009;39:347–364. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Education and Welfare. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1964. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Drobes DJ. Cue reactivity in alcohol and tobacco dependence. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:1928–1929. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040983.23182.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Jaén C, Baker T, Bailey W, Benowitz N, Currie S, Dorfman S, Froelicher ES, Goldstein MG, Healton CG, Henderson PN, Heyman RB, Koh HK, Kottke TE, Lando HA, Mecklenburg RE, Mermelstein RJ, Mullen PD, Orleans CT, Robinson L, Stitzer ML, Tommasello AC, Villejo L, Wewers ME. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Jiang L, Richter KP. Cigarette smoking cessation services in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2008;34:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BE, Guydish J, Tsoh J, Reid MS, Resnick M, Zammarelli L, Ziedonis DM, Sears C, McCarty D. Attitudes toward the integration of smoking cessation treatment into drug abuse clinics. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;32:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Chan M, Chun J, Bostrom A. Smoking prevalence in addiction treatment: a review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13:401–411. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Manser ST. Staff smoking and other barriers to nicotine dependence intervention in addiction treatment settings: a review. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:423–433. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Chan M, Delucchi KL, Ziedonis D. Measuring smoking knowledge, attitudes and services (S-KAS) among clients in addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;114:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Kulaga A, Zavalo R, Brown LS, Bostrom A, Chan M. The New York policy on smoking in addiction treatment: findings after one year. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300590. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Warnick TA, Plemmons S. Smoking cessation in drug treatment programs. J. Addict. Dis. 1999;18:89–101. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JT, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Patten CA, Hurt RD, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC. Response to nicotine dependence treatment in smokers with current and past alcohol problems. Ann. Behav. Med. 1999;21:244–250. doi: 10.1007/BF02884841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AL, Kantor B, Leech T, Lindberg D, Order-Connors B, Schreiber J, Slade J. Drug-free is Nicotine-free: A Manual for Chemical Dependency Treatment Programs. New Brunswick, NJ: Tobacco Dependence Program; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AL, Slade J. Following the pioneers. Addressing tobacco in chemical dependency treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Prev. Med. 1994;23:61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. Do smokers with current or past alcoholism need different or more intensive treatment? Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:1934–1935. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000041282.57396.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Treating smokers with current or past alcohol dependence. Am. J. Health Behav. 1996;20:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Croghan IT, Offord KP, Eberman KM, Morse RM. Attitudes toward nicotine dependence among chemical dependence unit staff—before and after a smoking cessation trial. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1995;12:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00024-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ., III Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment: role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA. 1996;275:1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM. Nicotine treatment at the Drug Dependency Program of the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. A researcher’s perspective. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Arikian NJ, An LC, Nugent SM, Sloan RJ, Pieper CF. Results of a randomized controlled trial of intervention to implement smoking guidelines in Veterans Affairs medical centers: increased use of medications without cessation benefit. Med. Care. 2004;42:1100–1110. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Nichol KL, Anderson H. Effect of treatment for nicotine dependence on alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Addict. Behav. 1993;18:635–644. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Nichol KL, Willenbring ML, Korn JE, Lysaght LS. Beneficial effects of treatment of nicotine dependence during an inpatient substance abuse treatment program. JAMA. 1990;263:3043–3046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK. Smoking cessation services in adolescent substance abuse treatment: opportunities missed? J. Drug Issues. 2009;9:257–276. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Studts JL, Boyd S, Roman PM. Structural and cultural barriers to the adoption of smoking cessation services in addiction treatment organizations. J. Addict. Dis. 2010;29:294–305. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.489446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Jelinek LC, Pope MA. Cigarette smoking among alcohol abusers: a continuing and neglected problem. Can. J. Public Health. 1986;77:205–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Skinner W, Kent C, Pope MA. Prospects for smoking treatment in individuals seeking treatment for alcohol and other drug problems. Addict. Behav. 1989;14:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, Coffey RM, Buck JA. Trends in spending for substance abuse treatment, 1986–2003. Health Aff. 2007;26:1118–1128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks JL, Hill EM, Pomerleau CS, Mudd SA, Blow FC. Nicotine dependence and withdrawal in alcoholic and nonalcoholic ever-smokers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1997;14:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JE, Calfas KJ, Patten CA, Polarek M, Hofstetter CR, Noto J, Beach D. Prospective evaluation of three smoking interventions in 205 recovering alcoholics: one-year results of Project SCRAP-Tobacco. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997;65:190–194. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool RM, Richter KP, Choi WS. Benefits of and barriers to providing smoking treatment in methadone clinics: findings from a national study. Am. J. Addict. 2005;14:358–366. doi: 10.1080/10550490591003693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CA, Roberts S, Descheemaeker N. Intentions to quit smoking in substance-abusing teens exposed to a tobacco program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2000;18:291–308. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD. Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Q. 1995;73:19–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAADAC. n.d. Position statement: nicotine dependence. http://www.naadac.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=236&Itemid=82 (retrieved 29.11.10)

- New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. Tobacco-Free Services: 2008 Title 14 NYCRR Part 856. 2008 http://www.oasas.state.ny.us/regs/856.cfm (retrieved 29.11.10)

- Olsen Y, Alford DP, Horton NJ, Saitz R. Addressing smoking cessation in methadone programs. J. Addict. Dis. 2005;24:33–48. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Arnsten JH. A rationale and model for addressing tobacco dependence in substance abuse treatment. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy. 2006;1:23. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Choi WS, McCool RM, Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS. Smoking cessation services in U.S. methadone maintenance facilities. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004;55:1258–1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothrauff TC, Eby LT. Counselors’ knowledge of the adoption of tobacco cessation medications in substance abuse treatment programs. Am. J. Addict. 2010;20:56–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustin TA. Incorporating nicotine dependence into addiction treatment. J. Addict. Dis. 1998;17:83–108. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Ann. Rev. Public Health. 2010;31:297–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SA, Warner KE. Don’t forget tobacco. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:201–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1003883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sees KL, Clark HW. When to begin smoking cessation in substance abusers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J, Schwartz S, Nightingale T, Novak S. Targeting nicotine addiction in a substance abuse program. Sci. Pract. Perspect. 2003:33–40. doi: 10.1151/spp032133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade J, Hoffman AL. Addressing Tobacco in the Treatment and Prevention of Other Addictions: Steps for Becoming Tobacco-free. New Brunswick, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB. Alcohol and tobacco: clinical and treatment issues. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:1954–1955. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000041008.52475.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyt E, Order-Connors B, Ziedonis D. Addressing tobacco through program and system change in mental health and addiction settings. Psychiatr. Ann. 2003;33:447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Stuyt EB. Recovery rates after treatment for alcohol/drug dependence. Tobacco users vs. non-tobacco users. Am. J. Addict. 1997;6:159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2009. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S. Smoking cessation among persons in recovery. Subst. Use Misuse. 2002;37:1275–1298. doi: 10.1081/ja-120004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima B, Guydish J, Delucchi K, Passalacqua E, Chan M, Moore M. Staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding nicotine dependence differ by setting. J. Drug Issues. 2009;39:365–384. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto A, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Kozlowski LT. Effect of cigarette smoking on alcohol treatment outcome. J. Subst. Abuse. 1995;7:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint DW, VanDeMark NR, Silverstein M, Stone E. Exploring factors related to readiness to change tobacco use for clients in substance abuse treatment. J. Drug Issues. 2009;39:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh JY, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Stopping smoking during first year of substance use treatment predicted 9-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;114:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Massachusetts Medical School and Department of Psychiatry. n.d. UMass Addressing Tobacco Through Organization Change (ATTOC) Consultation and Training Institute. http://www.umassmed.edu/psychiatry/ATTOC.aspx (retrieved 29.11.10)

- Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health. n.d. Recovery Plus Tobacco Project. http://www.dsamh.utah.gov/recovery_plus_tobacco_project.html (retrieved 29.11.10)

- Williams JM, Foulds J, Dwyer M, Order-Connors V, Springer M, Gadde P, Ziedonis DM. The integration of tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco-free standards into residential addictions treatment in New Jersey. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;28:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco Key Facts. 2010 http://www.who.int/topics/tobacco/facts/en/index.html (retrieved 29.11.10)

- Ziedonis DM, Zammarelli L, Seward G, Oliver K, Guydish J, Hobart M, Meltzer B. Addressing tobacco use through organizational change: a case study of an addiction treatment organization. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:451–459. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, Ulbrich PM, Auth JB. The relationship between alcohol use and attempts and success at smoking cessation. Addict. Behav. 1990;15:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]