Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinicopathological features and analyze the prognostic factors of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Patients and Methods

The clinical data of 1,788 breast cancer patients was collected and analyzed. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival. Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors for survival was performed using the Cox regression model.

Results

Patients with TNBC exhibited characteristics significantly differing from those with non-TNBC. There was a higher proportion of patients with age < 35 years, stage III disease, tumor size > 5 cm, lymph node positivity, and histological grade 3. The 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates of TNBC and non-TNBC patients were 75.7 and 79.6%, respectively (p < 0.05). 5-year overall survival (OS) was 86.6 and 93.5%, respectively (p < 0.05). In multivariate Cox regression analysis, the independent prognostic factors for shorter DFS were age < 35 years (hazard ratio (HR) 2.105), positive lymph nodes (HR 7.039), histological grade 3 (HR 1.841), and for shorter OS positive lymph nodes (HR 4.626).

Conclusion

The proportion of TNBC in breast cancer in China is higher than in other areas. TNBC is correlated with younger age, larger tumor size, positive lymph nodes, higher clinical stage and histological grade, and lower DFS and OS, which is consistent with previous reports.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features, prognosis; Multivariate analysis

Abstract

Hintergrund

Ziel dieser Studie war es, die klinischpathologischen Merkmale und Prognosefaktoren des tripel-negativen Mammakarzinoms (triple-negative breast cancer, TNBC) zu untersuchen.

Patienten und Methoden

Die klinischen Daten von 1.788 Mammakarzinom-Patientinnen wurden erhoben und analysiert. Die Kaplan-Meier-Methode wurde zur Berechnung des Überlebens eingesetzt. Die Multivariatanalyse der Prognosefaktoren bezüglich des Überlebens wurde nach dem Cox-Regressionsmodell durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse

Verglichen mit anderen Formen des Brustkrebs wiesen Patientinnen mit TNBC signifikant abweichende Merkmale auf. Es bestand ein höherer Anteil an Patientinnen im Alter von < 35 Jahren, Erkrankungen im Stadium III, Tumorgröße > 5 cm, positivem Lymphnknotenstatus und histologischem Grad 3. Das erkrankungsfreie Überleben über 5 Jahre von Patientinnen mit TNBC bzw. nicht-TNBC war 75,7 bzw. 79,6% (p < 0,05). Das Gesamtüberleben über 5 Jahre war 86,6 bzw. 93,5% (p < 0,05). Die multivariate Cox-Regressionsanalyse ergab folgende unabhängige Prognosefaktoren für ein kürzeres erkrankungsfreies Überleben: Alter < 35 Jahre (Hazard-Ratio (HR) 2,105), positiver Lymphknotenstatus (HR 7,039) und histologischer Grad 3 (HR 1,841). Bezüglich des kürzeren Gesamtüberlebens war ein positiver Lymphknotenstatus ein unabhängiger Prognosefaktor (HR 4,626).

Schlussfolgerung

Der Anteil an TNBC-Patientinnen ist höher in China als in anderen Regionen. TNBC ist mit einem jüngeren Alter, größeren Tumoren, positivem Lymphknotenstatus, einem höheren klinischen Stadium und histologischen Grad sowie einem niedrigeren erkrankungsfreien Überleben und Gesamtüberleben korreliert. Dies ist im Einklang mit anderen Berichten.

Introduction

Breast cancer has become one of the most common cancers in women. Recent studies suggest that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, and that patients with similar clinicopathologic features could show dramatically different clinical outcomes [1]. Therefore, to improve treatment outcome and reduce mortality, it is critical to further understand the biology of the disease [2, 3]. Based on gene expression profiling, 5 subtypes of breast cancer can be distinguished: luminal A, luminal B, normal breast-like, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu)-overexpressing, and basal-like. Each subtype has a different prognosis [4, 5]. Basal-like breast cancer is also named triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), defined as estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER-2/neu-negative. Although the incidence of TNBC is relatively low (10–20.8%), the extremely aggressive biological behavior of this disease leads to a poor prognosis [6, 7]. In this study, we collected the data of 356 cases of TNBC and analyzed their clinicopathologic and prognostic characteristics in order to provide a reliable basis for the treatment of TNBC.

Patients and Methods

Patients

A total of 1,778 patients who had received a histologically confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer between June 2003 and December 2004 constituted the study cohort. Patients with clinical state IV were excluded from this analysis. Complete clinical information and follow-up data of all patients including general status, pathological diagnosis, tumor stage, treatment, and survival status were collected. ER, PR, and HER-2/neu status were determined using immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. Tumors with more than 10% positive cells were considered ER/PR-positive. According to the clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), HER-2/neu IHC staining of 0 or + is judged to be negative, staining of +++ is positive, and staining of ++ should be further validated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). In this study, IHC staining of ++ without FISH analysis was classified as positive. Breast cancer with ER, PR, and HER-2/neu negativity is defined as TNBC. The remaining cases are termed non-TNBC. The clinicopathologic features of the 1,778 breast cancer patients are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features of TNBC and non-TNBC patients

| Clinical features | TNBC (n = 356) | non-TNBC (n = 1,422) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median DFS, months | 38.5 | 41.0 | 0.012 |

| Median OS, months | 43.0 |

46.5 | 0.004 |

| n (%) |

|||

| Age, years | |||

| < 35 | 30 (8.4) | 50 (3.5) | < 0.001 |

| $$ 35 | 326 (91.6) | 1,372 (96.5) | |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Premenopausal | 188 (52.8) | 800 (56.3) | 0.241 |

| Postmenopausal | 168 (47.2) | 622 (43.7) | |

| Family history | |||

| No | 274 (77.0) | 1,140 (80.2) | 0.180 |

| Yes | 82 (23.0) | 282 (19.8) | |

| Stage | |||

| I + II | 278 (78.1) | 1,185 (83.3) | 0.020 |

| III | 78 (21.9) | 237 (16.7) | |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| $$ 5 | 307 (86.2) | 1,323 (93.0) | < 0.001 |

| 5 | 49 (13.8) | 99 (7.0) | |

| Lymph node | |||

| Negative | 155 (43.5) | 720 (50.6) | 0.017 |

| Positive | 201 (56.5) | 702 (49.4) | |

| Histological grade | |||

| 1 + 2 | 280 (78.7) | 1,214 (85.4) | 0.002 |

| 3 | 76 (21.4) | 208 (14.6) | |

| Tumor type | |||

| Invasive ductal | 229 (64.3) | 974 (68.5) | 0.133 |

| Other | 127 (35.7) | 448 (31.5) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 321 (90.2) | 1,276 (89.7) | 0.808 |

| No | 35 (9.8) | 146 (10.3) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 86 (24.2) | 399 (28.1) | 0.139 |

| No | 270 (75.8) | 1,023 (71.9) | |

| Surgery | |||

| Radical | 114 (32.0) | 320 (22.5) | 0.001 |

| Modified radical | 223 (62.6) | 984 (69.2) | |

| Other | 19 (5.3) | 118 (8.3) |

TNBC = Triple-negative breast cancer; DFS = disease-free survival; OS = overall survival.

Follow-Up

Follow-up was completed by reviewing the clinical charts and directly contacting the patients. The median follow-up time was 46.5 months. Estimation of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) was the main objective of this survey. DFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to development of clinical or radiographic metastatic disease or to the last follow-up without disease. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the last follow-up or time of death.

Data Analysis

SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Baseline demographic and tumor characteristics were compared between the TNBC and non-TNBC groups using Pearson's chi-square test for frequency. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were carried out for DFS and OS with known prognostic variables such as age, tumor size, stage, lymph node, tumor type, and family history. The log-rank test was used to examine the statistical significance of the differences observed between the groups. For those found to be significantly associated with DFS and OS in univariate analysis (table 2), hazard ratios were calculated using multivariate Cox regression analysis. Estimates were considered statistically significant for two-tailed values of p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis to determine the association of baseline characteristics with DFS and OS in TNBC patients

| Clinical features | Cases, n | DFS, % | p | OS, % | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 years | 5 years | 3 years | 5 years | ||||

| Entire TNBC cohort | 356 | 84.0 | 76.7 | 92.6 | 87.1 | ||

| Age, years | |||||||

| < 35 | 30 | 76.4 | 53.1 | 0.016 | 93.0 | 80.1 | 0.512 |

| ≥ 35 | 326 | 84.7 | 78.9 | 92.6 | 87.7 | ||

| Menopausal status | |||||||

| Premenopausal | 188 | 87.4 | 76.3 | 0.283 | 94.9 | 88.5 | 0.160 |

| Postmenopausal | 168 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 90.1 | 85.0 | ||

| Family history | |||||||

| No | 274 | 82.4 | 72.5 | 0.060 | 91.5 | 83.5 | 0.074 |

| Yes | 82 | 88.8 | 85.3 | 96.0 | 96.0 | ||

| Stage | |||||||

| I + II | 278 | 86.3 | 80.4 | 0.003 | 95.1 | 90.1 | 0.022 |

| III | 78 | 76.3 | 60.9 | 84.7 | 75.8 | ||

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||

| ≤ 5 | 307 | 85.0 | 78.8 | 0.019 | 94.4 | 90.0 | 0.014 |

| 5 | 49 | 77.8 | 57.4 | 83.1 | 68.0 | ||

| Lymph node | |||||||

| Negative | 155 | 95.8 | 94.8 | < 0.001 | 99.1 | 94.9 | 0.001 |

| Positive | 201 | 74.8 | 61.4 | 87.6 | 80.1 | ||

| Histological grade | |||||||

| 1 + 2 | 280 | 87.1 | 78.2 | 0.003 | 93.8 | 87.6 | 0.185 |

| 3 | 76 | 72.6 | 67.1 | 88.4 | 83.2 | ||

| Tumor type | |||||||

| Invasive ductal | 229 | 80.5 | 70.4 | 0.019 | 90.4 | 82.9 | 0.056 |

| Other | 127 | 89.7 | 84.3 | 96.3 | 92.8 | ||

| Surgery | |||||||

| Radical | 114 | 85.1 | 85.1 | 0.138 | 91.0 | 85.2 | 0.437 |

| Modified radical | 223 | 83.4 | 71.2 | 93.4 | 87.2 | ||

TNBC = Triple-negative breast cancer; DFS = disease-free survival; OS = overall survival.

Results

Clinicopathologic Features of TNBC Patients

In this sample, 356 of the 1,778 patients (20%) were defined as having TNBC. The disease stages were I–III; hence, the vast majority of patients was surgically treated. Patients with TNBC exhibited characteristics significantly different to those of patients with non-TNBC (table 1), namely a higher proportion of age < 35 years (p < 0.001), stage III (p = 0.020), tumor size > 5 cm (p < 0.001), lymph node positivity (p = 0.017), and histological grade 3 (p = 0.002).

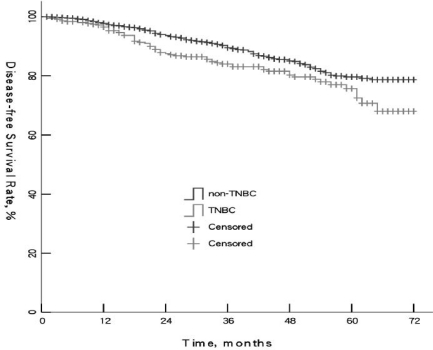

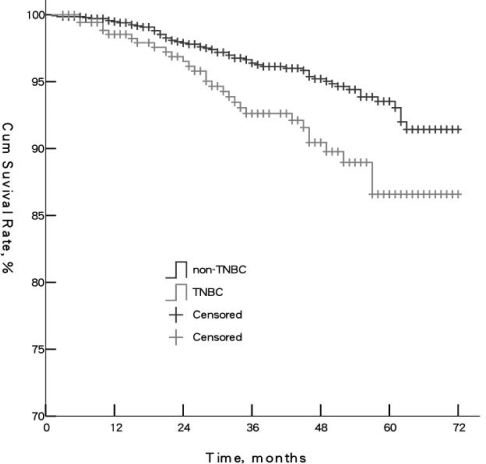

Survival Rates for TNBC and Non-TNBC Patients

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were carried out to compare DFS and OS. Median DFS of TNBC and non-TNBC was 38.5 and 41 months, respectively (p = 0.012). Median OS was 43 and 46.5 months, respectively (p = 0.004). 5-year DFS rates of TNBC and non-TNBC were 75.7 and 79.6%, respectively. 5-year OS rates were 86.6 and 93.5%, respectively. The 2 groups were significantly different (p < 0.05) (figs. 1 and 2). Survival rates in the TNBC group showed the most significant decline during month 15–25 of follow-up, which indicated TNBC patients had higher risk of metastasis and death during that time.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of overall survival of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and non-TNBC patients (p = 0.003).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of overall survival of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and non-TNBC patients (p = 0.003).

Univariate Analysis of Prognosis in TNBC

Clinical parameters significantly associated with shorter DFS were age < 35 years (p = 0.016), clinical stage III (p = 0.003), tumor size > 5 cm (p = 0.019), lymph node positivity (p < 0.001), histological grade 3 (p = 0.003), invasive ductal pathological type (p = 0.019). Prognostic factors associated with shorter OS were clinical stage III (p = 0.022), tumor size > 5 cm (p = 0.014), and lymph node positivity (p = 0.001) (table 2).

Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of Prognosis in TNBC

In multivariate Cox regression analysis, bicategorical pretreatment baseline characteristics that showed significance for DFS in the univariate analysis (table 2) were included: age, clinical stage, tumor size, lymph node status, histological grade, and pathological type. It became evident that the following parameters were independent for shorter DFS: age < 35 years (hazard ratio (HR) 2.105, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08–4.13, p = 0.006); positive lymph nodes (HR 7.039, 95% CI 2.95–16.78, p < 0.001); and histological grade 3 (HR 1.841, 95% CI 1.07–3.18, p < 0.001). The independent prognostic factor for shorter OS was positive lymph node status (HR 4.626, 95% CI 1.54–13.93, p = 0.006).

Discussion

As a special subtype of breast cancer, TNBC has attracted more attention both clinically and experimentally. It has been reported that TNBC is characterized by the following biological features: large tumor size; high histological grade; expression of basal cytokeratin (CK5/6, CK17), P-cadherin, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and P53 in most cases; and rare expression of androgen receptor, E-cadherin, and cyclin D. DFS and OS are lower than in non-TNBC, and local recurrence and distant metastasis tend to appear earlier [8]. Because of its high-risk biological characteristics, TNBC exhibits less drug targets, resulting in less effective treatment options and lack of benefit from endocrine and targeted therapies for patients [9, 10].

In the current study, we collected and analyzed the data of 1,778 Chinese breast cancer patients in order to explore new therapeutic strategies for TNBC. 356 (20%) of the 1,778 breast cancer patients had TNBC, which was consistent with rates from a previous report from Korea by Rhee et al. [11]. Other reports show rates of 13.4% (America) [12] and 11.2% (Canada) [4], while another study from China reported an incidence as high as 24% [13]. This discrepancy may be due to different ethnic backgrounds of the cohorts, or varying test methods and standards. Identification of the exact reasons would require multicenter trials with more patients. Compared with non-TNBC, TNBC was correlated with younger age (< 35 years, 8.4%), larger tumor size, more positive axillary lymph nodes, and higher histological and pathologic grade, which was consistent with previous reports [6, 14].

Brown et al. [15] showed 5-year OS rates of 76.2% for TNBC, compared to 75.9% in ER(–), PR(–), HER-2-overexpressing breast cancer patients and 94.2% for the remaining types of breast cancer. Dent et al. [4] conducted a long-term follow-up study of TNBC patients and found that recurrence and death mainly occurred in the first 5 years after surgery. Our study showed that 5-year DFS (75.7%) and 5-year OS (86.6%) were significantly lower in TNBC compared to non-TNBC patients, which was similar to other reports. The slightly different survival rates among these studies may be caused by personal circumstances, treatment methods, and different levels of medical care in local hospitals [16, 17]. Some trials revealed that the sensitivity to chemotherapy of TNBC was comparable or even higher than that of other types of breast cancer. The reason for the poor prognosis of TNBC may be special biological characteristics such as non-susceptibility to endocrine and targeted therapy. Because of this, TNBC patients are left without an ideal adjuvant therapy after conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy to prevent metastasis and recurrence [10, 18, 19]. Siziopikou et al. [20] reported that TNBC expresses EGFR. In a multicenter randomized phase II clinical trial, 120 patients with metastatic TNBC were randomized to receive gemcitabine and carboplatin with or without BSI-201. The total relative risk was significantly higher in patients with BSI-201 than in those without (48 vs. 15%; p = 0.002), and the clinical benefit rate (complete remission + partial remission + stable disease > 6 months) was significantly increased (62 vs. 21%; p = 0.0002) [21]. This highlights the future possibilities of platinum therapy in combination with PARP-1 inhibitors for TNBC.

In the present study, univariate analysis showed that the factors affecting DFS in TNBC patients were age, clinical stage, tumor size, lymph node status, histological grade, and pathological type. Factors affecting the OS were clinical stage, tumor size, and lymph node status. Bauer et al. [22] pointed out that younger TNBC patients had faster recurrence and metastasis, which is closely related to their high level of estrogen and progesterone. Other reports showed that premenopausal breast cancer patients with a poor prognosis are more likely to develop local recurrence and distant metastasis [18, 23]. These results indicate that during follow-up, particular attention must be paid to younger TNBC patients in order to treat them immediately when the disease progresses. Clinical stage and histological grade are significantly related to the prognosis of TNBC: the higher the pathological stage and histological grade of the tumor, the lower the DFS and OS of the patient. Furthermore, patients with positive lymph nodes have a poor prognosis. One study further analyzed the relationship between number and location of the positive lymph nodes and prognosis but did not find any significant correlation [24]. In clinical treatment, node-positive TNBC patients should not only receive adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy but also biological treatments and other new therapy methods. Postoperative follow-up is also critical in improving the prognosis.

There are some limitations to our study. First, in some cases, IHC staining for ER, PR, or HER-2 had not been performed, and follow-up data were missing in several cases whose survival status was therefore difficult to analyze. Second, CerbB-2(–) and (+) were classified as HER-2/neu-negative and considered as TNBC, while CerbB-2(++) and (+++) were classified as HER-2/neu-positive and non-TNBC. However, a number of trials showed that classification of CerbB-2(++) as HER-2/neu-positive or -negative did not affect the clinical outcome [25]. Third, some patients with short follow-up should be observed longer in order to analyze the changes in recurrence hazard in the long term, which would provide information for physicians when choosing a treatment plan.

In summary, this data from China showed that the proportion of TNBC in breast cancer patients (20%) was higher than that published for other areas. This discrepancy may be due to different ethnic backgrounds of the cohorts or varying test methods and standards. 5-year DFS (75.7%) and 5-year OS (86.6%) were significantly lower for TNBC than for non-TNBC, which is similar to other reports. In our study, TNBC was correlated with young age, large tumor size, positive lymph nodes, and higher clinical stage and histological grade, which is consistent with previous reports from other countries. Additional efforts should be directed towards standardization of current test methods and development of new treatment strategies.

Disclosure Statement

No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and the manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

References

- 1.Kinne DW, Butler JA, Kimmel M, et al. Estrogen receptor protein of breast cancer in patients with positive nodes: high recurrence rates in the postmenopausal estrogen receptor-negative group. Arch Surg. 1987;122:1303–1306. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1987.01400230089016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parl FF, Schmidt BP, Dupont WD, et al. Prognostic significance of estrogen receptor status in breast cancer in relation to tumor stage, axillary node metastasis, and histopathologic grading. Cancer. 1984;54:2237–2242. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841115)54:10<2237::aid-cncr2820541029>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichon MF, Broet P, Magdelenat H, et al. Prognostic value of steroid receptors after long-term follow-up of 2257 operable breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1545–1551. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakha EA, El Sayed ME, Green AR. Prognostic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K, et al. Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5367–5374. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee S, Reis-Filho JS, Ashley S, et al. Basal-like breast carcinomas: clinical outcome and response to chemotherapy. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:729–735. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.033043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keam B, Im SA, Kim HJ, Oh DY, Kim JH, Lee SH, Chie EK, Han W, Kim DW, Moon WK, et al. Prognostic impact of clinicopathologic parameters in stage II/III breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant docetaxel and doxorubicin chemotherapy: paradoxical features of the triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleator S, Heller W, Coombes RC. Triple-negative breast cancer: therapeutic options. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee J, Han SW, Oh DY, et al. The clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic significance of triple-negativity in node-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onitilo AA, Engel JM, Greenlee RT, Mukesh BN. Breast cancer subtypes based on ER/PR and Her2 expression: comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival. Clin Med Res. 2009;7:4–13. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2009.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan ZY, Wang SS, Gao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer: a report of 305 cases. Ai Zheng. 2008;27:561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mersin H, Yildirim E, Berberoglu U, Gülben K. The prognostic importance of triple negative breast carcinoma. Breast. 2008;17:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown M, Tsodikov A, et al. The role of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in the survival of women with estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, invasive breast cancer: the California Cancer Registry, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2008;112:737–747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field TS, Buist DS, Doubeni C, et al. Disparities and survival among breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:88–95. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joslyn SA. Hormone receptors in breast cancer: racial differences in distribution and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;73:45–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1015220420400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroger N, Milde-Langosch K, Riethdorf S, et al. Prognostic and predictive effects of immunohistochemical factors in high-risk primary breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:159–168. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, et al. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5678–5685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siziopikou KP, Cobleigh M. The basal subtype of breast carcinomas may rep resent the group of breast tumors that could benefit from EGFR – targeted therapies. Breast. 2007;16:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Shaughnessy J, Osborne C, Pippen J, et al. Efficacy of BSI-201, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine/carboplatin (G/C) in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol (meet abstr) 2009;27:15S. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, et al. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109:l721–728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleator S, Heller WR, Coombes C. Triple-negative breast cancer: therapeutic options. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grann VR, Troxel AB, Zojwalla NJ, Jacobson JS, Hershman D, Neugut AI. Hormone receptor status and survival in a population-based cohort of patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:2241–2251. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haffty BG, Yang Q, Reiss M, Kearney T, Higgins SA, Weidhaas J, Harris L, Hait W, Toppmeyer D. Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5652–5657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]