Abstract

Yersinia enterocolitica is the most common bacteriological cause of gastrointestinal disease in many developed and developing countries. Although contaminated food is the main source of human infection due to Y. enterocolitica, animal reservoir and contaminated environment are also considered as other possible infection sources for human in epidemiological studies. Molecular based epidemiological studies are found to be more efficient in investigating the occurrence of human pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in natural samples, in addition to conventional culture based studies.

1. Introduction

Foodborne diseases are a widespread and growing public health problem in developed and developing countries [1]. Amongst those, yersiniosis due to infection with the bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica is the frequently reported zoonotic gastrointestinal disease after campylobacteriosis and salmonellosis in many developed countries, especially in temperate zones [2]. Within developed countries, incidences of yersiniosis and foodborne outbreaks are appeared to be lower in the United States than many European countries [3–5]. In European countries, numbers of reported cases of human in England and Wales are lower than those in other European countries where fewer than 0.1 cases of yersiniosis per 100,000 individuals were reported in the United Kingdom in 2005, in contrast to 12.2 in Finland and 6.8 in Germany [6]. On the other hand, the high prevalence of gastrointestinal illness including fatal cases due to yersiniosis is also observed in many developing countries like Bangladesh [7], Iraq [8], Iran [9], and Nigeria [10], which indicates major underlying food safety problems in low- and middle-income countries. Worldwide, infection with Y. enterocolitica occurs most often in infants and young children with common symptoms like fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which is often bloody. Older children and young adults are not out of risk. The predominant symptoms within these age groups are right-sided abdominal pain and fever, sometimes confused with appendicitis. Occasionally, the Y. enterocolitica associated complications such as skin rash, joint pains, or spread of bacteria to the bloodstream can also occur.

Although Y. enterocolitica is a ubiquitous microorganism, the majority of isolates recovered from asymptomatic carriers, infected animals, contaminated food, untreated water, and contaminated environmental samples are nonpathogenic having no clinical importance [11]. At the same time, the epidemiology of Y. enterocolitica infections is complex and remains poorly understood because most sporadically occurred cases of yersiniosis are reported without an apparent source [3, 12–14]. However, most pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains associated with human yersiniosis belong to bioserotypes 1B/O:8, 2/O:5,27, 2/O:9, 3/O:3, and 4/O:3. Within these reported strains, fully pathogenic strains carry an approximately 70 kb plasmid termed pYV (plasmid for Yersinia virulence) [15] that encodes various virulence genes (tccC, yadA, virF, ysa) with traditional chromosomal virulence genes (inv, ail, yst) whereas other pathogenic strains, having no pYV plasmid, produce a thermostable enterotoxin (ystA) [16–18]. These virulence genes located in chromosome or plasmid of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica has been widely used to identify pathogenic strains in epidemiological studies for example, chromosomal ail gene [19, 20].

2. Epidemiological Studies and Outbreaks

Many factors related to the epidemiology of Y. enterocolitica, such as human and nonhuman sources, and contamination routes in foods remain obscure in developing countries and tropical regions of developed countries. Additionally, epidemiological data on the prevalence of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in animals in developed countries are missing as the reporting of this pathogen in animals is not mandatory in most European countries [26].

2.1. Animal Reservoirs Involved in Zoonosis

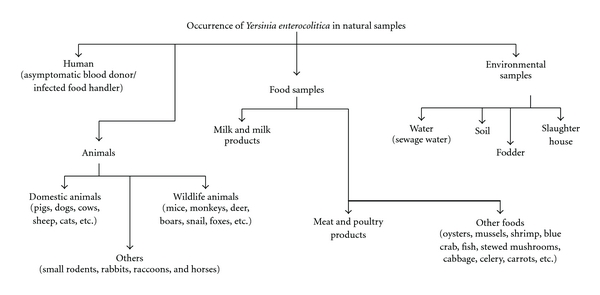

Animals have long been suspected of being significant reservoirs for Y. enterocolitica and, therefore, sources of human infections [3]. Numerous studies have been carried out to isolate Y. enterocolitica strains from a variety of animals (Figure 1) [56]. Interestingly, most of the strains isolated from the animal kingdom carry unique serotypes of Y. enterocolitica compared to the strains isolated from humans with yersiniosis.

Figure 1.

Occurrence of Y. enterocolitica in natural samples.

Pigs have been shown to be a major reservoir of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica involved in human infections, particularly for strains of bioserotype 4/O:3 which has been almost exclusively isolated in European countries like Denmark, Italy, Belgium, Spain, and Sweden [24, 64]. The rate of isolation of Y. enterocolitica including bioserotype 4/O:3 from tonsils and tongues of pigs is generally greater than the rate of isolation from cecal or fecal materials [20].

Occasionally, pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains, mostly of bioserotype 4/O:3, have also been isolated from dogs and cats [82]. Although pigs are the primary source of human infection with Y. enterocolitica throughout world, these pets may also be a potential source of human infection with pathogenic Y. enterocolitica because of their intimate contact with people, especially young children [28].

In addition with mostly isolated bioserotype 4/O:3, Y. enterocolitica strains of biotypes 2 and 3 and serotypes O:5,27, O:8, and O:9 have also been isolated from slaughter pigs, cows, sheep, and goats; however, the reservoir of these bioserotypes is not clearly established [81, 83–85]. In above cases, contamination of pluck sets (tongue, tonsils, and trachea hanging together with thoracic organs such as lungs, liver, and heart) and carcasses with enteropathogenic Yersinia from tonsils and feces may occur during the slaughtering stage [5, 82, 86–88]. On the other hand, strains of very rare bioserotypes, such as bioserotype 5/O:2,3, have been isolated from sheep, hares, and goats and bioserotype 3/O:1,2a,3 from chinchillas (small rodent). Thus, the patterns of the pathogenic strains isolated from humans with yersiniosis compared to those from the animals suggest that the human infection due to Y. enterocolitica originated from the animals.

2.2. Contaminated Food Involved in Infections

Food has been proposed to be the main source of intestinal yersiniosis although pathogenic isolates have seldom been recovered from food samples [105]. The low recovery rates of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in food samples may be due to limited sensitivity of culture methods [11]. However, Y. enterocolitica has been isolated from milk and milk products, egg products, raw meats (beef, pork, and lamb) and poultry, vegetables, and miscellaneous prepared food products. The occurrence of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in natural sample including foods has been estimated by both culture- and molecular-based methods (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in natural samples with PCR and culture methods.

| Sample | No. of samples | No. of culture+vesamplesa (%) | No. of PCR+vesamples (%) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | ||||||

| Pig tonsils | 185 | 48 | (26) | 58 | (31) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [21] |

| 252 | 0 | 90 | (36) | Boyapalle et al. [22] | ||

| 24 | 15 | (63) | 18 | (75) | Nesbakken et al. [23] | |

| 829 | 411 | (50) | 0 | Martínez et al. [24] | ||

| 630 | 278 | (44) | 0 | Martínez et al. [25] | ||

| 212 | 72 | (34) | 186 | (88) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [26] | |

| Pig faeces | 255 | 0 | 80 | (31) | Boyapalle et al. [22] | |

| 24 | 3 | (13) | 3 | (13) | Nesbakken et al. [23] | |

| 2793 | 114 | (4) | 345 | (12) | Bhaduri et al. [27] | |

| 150 | 3 | (2) | 0 | Okwori et al. [10] | ||

| Mesenteric l. n. | 257 | 0 | 103 | (40) | Boyapalle et al. [22] | |

| 24 | 1 | (4) | 2 | (8) | Nesbakken et al. [23] | |

| Submaxillary l. n. | 24 | 1 | (4) | 3 | (13) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [20] |

| Sheep feces | 200 | 2 | (1) | 0 | Okwori et al. [10] | |

| Dog feces | 448 | 0 | 6 | (1) | Wang et al. [28] | |

| Food b | ||||||

| Pig tongues | 15 | 7 | (47) | 10 | (67) | Vishnubhatla et al. [29] |

| 99 | 79 | (80) | 82 | (83) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa and Korkeala [11] | |

| Pig offalc | 110 | 38 | (35) | 77 | (70) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [20] |

| Chitterlings | 350 | 8 | (2) | 278 | (79) | Boyapalle et al. [22] |

| Ground pork | 350 | 0 | 133 | (38) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [20] | |

| 100 | 32 | (32) | 47 | (47) | Vishnubhatla et al. [29] | |

| Ground beef | 100 | 23 | (23) | 31 | (31) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [20] |

| Minced pork | 255 | 4 | (2) | 63 | (25) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa and Korkeala [11] |

| Porkd | 300 | 6 | (2) | 50 | (17) | Johannessen et al. [30] |

| 91 | 6 | (7) | 9 | (10) | Lambertz & Danielsson-Tham [31] | |

| 62 | 0 | 20 | (32) | Grahek-Ogden et al. [32] | ||

| Chicken | 43 | 0 | 0 | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [11] | ||

| Fish | 150 | 0 | 0 | Okwori et al. [10] | ||

| Heated soup | 100 | 3 | (3) | Okwori et al. [10] | ||

| Cow milk | 250 | 3 | (1) | Okwori et al. [10] | ||

| Lettuce | 250 | 0 | 3 | (3) | Okwori et al. [10] | |

| Tofu | 50 | 0 | 6 | (12) | Vishnubhatla et al. [29] | |

| Vegetables | 27 | 1 | (4) | 4 | (15) | Cocolin & Comi [33] |

| Salad | 42 | 16 | (38) | 16 | (38) | Sakai et al. [34] |

| Environment | ||||||

| Water | 105 | 1 | (1) | 11 | (10) | Sandery et al. [35] |

| Slaughterhouse/ Farm | 89 | 5 | (6) | 12 | (13) | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [36] |

| 46 | 44 | (96) | 0 | Martínez et al. [24] | ||

| 45 | 31 | (61) | 0 | Martínez et al. [25] | ||

aPathogenicity of isolates confirmed, ball meat samples are raw, cliver, heart, kidney, dexcept pig offal & tongues, and +vepositive.

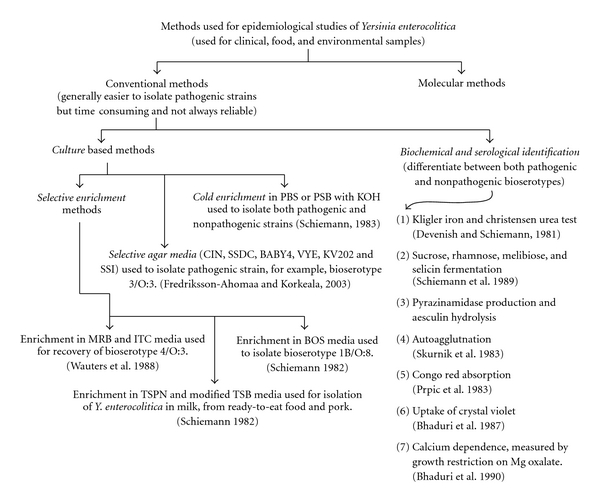

Figure 2.

Methods used for epidemiological studies of Y. enterocolitica-1. Selective enrichment methods [43]; selective agar media [11]; cold enrichment method [57]; biochemical & serological identification methods [58–63]. (PBS: Phosphate buffered saline; PSB: Phosphate-buffered saline with sorbitol and bile salts; MRB: Modified Rappaport broth containing magnesium chloride, malachite green, and carbenicillin; ITC: Modified Rappaport base supplemented with irgasan, ticarcillin, and potassium chlorate; BOS: Bile-oxalate-sorbose medium; TSB: Tryptic soy broth; TSPN: TSB with polymyxin and novobiocin; CIN: Cefsulodin-irgasan-novobiocin; SSDC: Salmonella-Shigella deoxycolate calcium chloride; VYE: Virulent Yersinia enterocolitica; SSI: Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark, enteric medium).

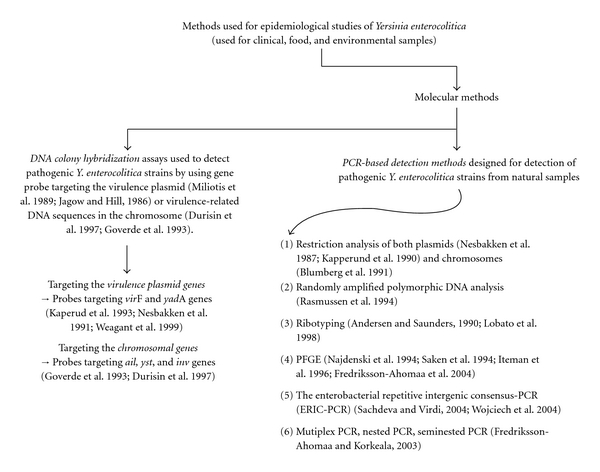

Figure 3.

Methods used for epidemiological studies of Y. enterocolitica-2. DNA colony hybridization assays [51, 65–70]; PCR based detection methods [11, 71–81]. (inv: gene for invasin, an outer membrane protein that is required for efficient translocation of bacteria across the intestinal epithelium; ail: gene for adhesin, an outer membrane protein that may contribute to adhesion, invasion and resistance to complement-mediated lysis; yst: gene for heat-stable enterotoxin that may contribute to the pathogenesis of diarrhea associated with acute yersiniosis; virF: gene for transcriptional activator; yadA, gene for Yersinia adhesin A; PFGE: pulsed field gel electrophoresis).

2.2.1. Contaminated Meat and Poultry Products Correlated with yersiniosis

Indirect evidence considering food, particularly pork and pork products, indicates that there is an important link between consumption of raw, undercooked, or improperly handled pork product and human Y. enterocolitica infections [20]. This positive correlation between the consumption of raw or undercooked pork and the prevalence of yersiniosis has been demonstrated in case-control studies [32, 64, 106–109]. Using molecular techniques, ail-positive Y. enterocolitica strains were detected in raw pork samples (loin, fillet, chop, ham, and minced meat) and in ready-to-eat pork products [31]. However, the isolation rates of pathogenic bioserotypes of Y. enterocolitica have been low in raw pork, except for in edible pig offal, with the most common type isolated being bioserotype 4/O:3 (Table 2). In other studies, pathogenic yst-positive Y. enterocolitica strains have been isolated from ground beef [29] but not detected in chicken food samples [110].

Table 2.

Detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in pork products by culture methods (partially adapted from Fredriksson-and Korkeala [11]).

| Sample |

No. of samples |

No. of samples positive for |

Country of origin of sample |

Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O:3 | O:5,27 | O:8 | O:9 | ||||

| Tongue | 302 | 165 | 3 | Belgium | Wauters [37] | ||

| 37 | 11 | Canada | Schiemann [38] | ||||

| 31 | 2 | 6 | USA | Doyle et al. [39] | |||

| 47 | 26 | Norway | Nesbakken [40] | ||||

| 50 | 20 | Japan | Shiozawa et al. [41] | ||||

| 125 | 8 | Spain | Ferrer et al. [42] | ||||

| 29 | 28 | Belgium | Wauters et al. [43] | ||||

| 40 | 6 | 2 | The Netherlands | de Boer and Nouws [44] | |||

| 55 | 14 | Germany | Karib and Seeger [45] | ||||

| 86 | 2 | Italy | de Guisti et al. [46] | ||||

| 99 | 79 | Finland | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [47] | ||||

| 20 | 15 | Germany | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [48] | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Tonsil | 89 | 81 | 8 | Belgium | Martínez et al. [24] | ||

| 137 | 136 | 1 | Italy | Martínez et al. [24] | |||

| 185 | 185 | Spain | Martínez et al. [24] | ||||

| 212 | 69 | 6 | 1 | Switzerland | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [26] | ||

|

| |||||||

| Offala | 34 | 17 | Finland | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [36] | |||

| 16 | 5 | Finland | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [47] | ||||

| 100 | 46 | Germany | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [48] | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Porkb | 91 | 1 | 1 | Canada | Schiemann [38] | ||

| 127 | 1 | Norway | Nesbakken et al. [49] | ||||

| 70 | 22 | 3 | Japan | Shiozawa et al. [41] | |||

| 267 | 6 | Denmark | Christensen [50] | ||||

| 50 | 12 | Belgium | Wauters et al. [43] | ||||

| 400 | 3 | 1 | The Netherlands | de Boer and Nouws [44] | |||

| 45 | 8 | Norway | Nesbakken et al. [51] | ||||

| 67 | 1 | 8c | 3 | China | Tsai and Chen [52] | ||

| 48 | 1 | 1 | Germany | Karib and Seeger [45] | |||

| 40 | 2 | 4 | 1 | Ireland | Logue et al. [53] | ||

| 1278 | 64 | 14 | Japan | Fukushima et al. [54] | |||

| 255 | 4 | Finland | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [55] | ||||

| 300 | 6 | Norway | Johannessen et al. [30] | ||||

| 120 | 14 | Germany | Fredriksson-Ahomaa et al. [36] | ||||

| 60 | 20 | Norway | Grahek-Ogden et al. [32] | ||||

aOffal, excluding tongue, bother pork products, excluding offal, cisolates belonging to serotype O:5 and showing autoagglutination activity and calcium-dependent growth.

2.2.2. Contaminated Milk and Milk Products Associated with Human Disease

Y. enterocolitica has been isolated from raw milk in many countries, like Australia, Canada, Czechoslovakia, and USA. There were also a few reports on the isolation of this pathogenic strain associated with human disease from pasteurized milk [4, 111]. It may be due to the malfunction in the pasteurization process leading to inadequate treatment or postprocess contamination, or it may be due to the contamination with heat-resistant strains of Y. enterocolitica. So, the presence of this pathogen in pasteurized milk should be a cause for concern. However, heat-resistant strains of Y. enterocolitica have not been still reported in milk samples.

2.2.3. Other Contaminated Foods Involved in Outbreaks

Strains of Y. enterocolitica have been isolated from oysters, mussels, shrimp, blue crab, fish, salad, stewed mushrooms, cabbage, celery, and carrots [112]. In Korea, Lee et al. [113] isolated ail-positive Y. enterocolitica strain of bioserotype 3/O:3 from ready-to-eat vegetables, which indicate that vegetables can be a source of human infection. Furthermore, Sakai et al. [34] reported an outbreak of food poisoning by Y. enterocolitica serotype O:8 in Japan where salad was proposed the cause of infection. Recently, Y. enterocolitica 2/O:9 has been isolated from chicken eggshell surfaces in Argentina [114]. Contamination of the egg surface might have occurred from contact with other Y. enterocolitica-contaminated animal products, such as pork product, during collection on farms or during transportation or handling in retail shops.

2.3. Contaminated Environment Reported as Source of Infection

Most of the Y. enterocolitica isolates recovered from environmental samples, including the slaughterhouse, fodder, soil, and water, have been nonpathogenic [89, 115–119]. Occasionally, strains of bioserotype 4/O:3 have been isolated from the slaughterhouse [120, 121] and sewage water [50]. Within the environmental sampling sites, drinking water has been relatively widely investigated and revealed to be a significant reservoir for nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica. However, Sandery et al. [35] detected pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in environmental water by molecular studies. In a case-control study, untreated drinking water has been reported to be a risk factor for sporadic Y. enterocolitica infections in Norway [107]. Recently, Falcão et al. [122] tested 67 Y. enterocolitica strains isolated in Brazil from untreated water for the presence of virulence genes. They found that all 38 strains of serotype O:5,27 possessed inv, ail, and yst genes, suggesting that untreated water may be responsible for the human infection with Y. enterocolitica. In another study, Y. enterocolitica O:8 strains have been isolated from stream water in Japan, which indicate that stream water may be a possible infection source for human Y. enterocolitica O:8 infections [84, 123].

3. Conclusion

Epidemiological studies of human infection with Y. enterocolitica (Table 3) constitute an important element in the exploitation of apparent sources and contamination routes of human yersiniosis and in the development and implementation of effective control strategies to prevent future outbreaks. Efficient laboratory methods used for epidemiological study are also a vital requirement in Y. enterocolitica's monitoring and control purposes. Molecular methods should be needed with conventional culture methods to provide a better estimation of epidemiology of Y. enterocolitica particularly pathogenic strains in natural samples

Table 3.

Epidemiological studies of human infection with Y. enterocolitica.

| Year | Country | Outcome of the study | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981–1990 | Georgia | Report of 84 clinical isolates of Y. enterocolitica, the most frequently reported serotypes were O:5; O:10,46; O:6,30 | Sulakvelidze et al. [89] |

| 1982–1991 | The Netherlands | Analysis of clinical information from 261 Dutch patients with gastrointestinal infections caused by Y. enterocolitica serotypes O:3 and O:9 | Stolk-Engelaar and Hoogkamp-Korstanje [90] |

| 1982a | Canada | Outbreak of gastroenteritis among hospitalized patients associated with Y. enterocolitica serotype O:5 | Ratnam et al. [91] |

| 1982–1985 | Canada | Examination of 125 isolates of Y. enterocolitica, serotypes O:7,8; O:5; O:6,30, were frequently obtained from symptomatic patients | Noble et al. [92] |

| 1983 | Finland | Report of 46 fecal isolates of Y. enterocolitica, including two serotypes O:7; O:6, associated with occurrence | Skurnik et al. [60] |

| 1984a | Bangladesh | Case report of a fatal diarrheal illness associated with serotypes O:7; O:8 | Butler et al. [7] |

| 1984a | Hong Kong | Report of Y. enterocolitica-associated septicemia in four patients regarding serotypes O:17 | Seto and Lau [93] |

| 1984-1985 | UK | Report of two nosocomial outbreaks of Y. enterocolitica serotypes O:10; O:6 infections in hospitalized children | Greenwood and Hooper [94] |

| 1986a | UK | Case report of nosocomial transmission of serotypes O:6,30 associated with gastroenteritis | McIntyre and Nnochiri [95] |

| 1986–1992 | Canada | Report of 79 symptomatic children with culture-proven infection, including serotypes O:5; O:6,30; O:7,8 | Cimolai et al. [96] |

| 1987 | UK | Report of 77 Y. enterocolitica strains from patients, including serotypes O:6,30; O:7 | Greenwood and Hooper [97] |

| 1987-1988 | Australia | Report of 11 cases of Y. enterocolitica enteritis, including most frequently serotypes O:6,30 | Butt et al. [98] |

| 1987–1989 | Chile | A prospective case-control study of infants with diarrhoea in Chile, showing a significantly reported serotypes O:6; O:7,8; O:7; O:10 | Morris et al. [99] |

| 1988–1991 | Nigeria | Of nine strains of Y. enterocolitica obtained from stool samples of children with diarrhoea | Onyemelukwe [100] |

| 1988–1993 | New Zealand | Of 918 isolates of Y. enterocolitica from symptomatic patients | Fenwick and McCarthy [101] |

| 1968–2000 | Brazil | Of 106 strains (selected from the collection of the Yersinia Reference Laboratory in Brazil), 71 were bioserotype 4/O:3, isolated from human and animal clinical material, and 35 were of biotype 1A or 2, isolated from food | Falcão et al. [102] |

| 2002 | Iran | Report of 8 cases of Y. enterocolitica infection out of 300 children with acute diarrhoea aged 0–12 years who were attending a pediatric hospital in Tehran | Soltan-Dallal and Moezardalan [9] |

| 2002–2004 | Nigeria | Detection of Y. enterocolitica belonging to bioserotype 2/O:9 in investigating 500 human samples | Okwori et al. [10] |

| 2004 | Japan | Report of 16 cases food poisoning due to Y. enterocolitica serotype O:8 | Sakai et al. [34] |

| 2005–2006 | Norway | Investigation of an outbreak involving 11 persons infected with Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 | Grahek-Ogden et al. [32] |

| 2001-2008 | Germany | Almost 90% of Y. enterocolitica strains were diagnosed as serotype O:3 | Rosner et al. [103] |

| 2009a | Iraq | Identification of three children with diarrhoea caused by Y. enterocolitica infection | Kanan and Abdulla [8] |

| 2009 | Australia | Report of 1 outbreak with 3 cases due to consumption of roast pork contaminated with Y. enterocolitica | OzFoodNet sites [104] |

aYear of publication.

References

- 1.Schlundt J. New directions in foodborne disease prevention. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2002;78(1-2):3–17. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yersinia. EFSA Journal. 2007;130:190–195. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997;10(2):257–276. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cover TL, Aber RC. Yersinia enterocolitica. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(1):16–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Linström M, Korkeala H. Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis . In: Juneja VK, Sofos NJ, editors. Pathogens and Toxins in Foods: Challenges and Interventions. ASM Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trends and sources of zoonoses and zoonotic agents in the European Union in 2007. EFSA Journal. 2009;223 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler T, Islam M, Islam MR, et al. Isolation of Yersinia enterocolitica and Y. intermedia from fatal cases of diarrhoeal illness in Bangladesh. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1984;78(4):449–450. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanan TA, Abdulla ZA. Isolation of Yersinia spp. from cases of diarrhoea in Iraqi infants and children. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2009;15(2):276–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soltan-Dallal MM, Moezardalan K. Frequency of Yersinia species infection in paediatric acute diarrhoea in Tehran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2004;10(1-2):152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okwori AEJ, Martínez PO, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Agina SE, Korkeala H. Pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica 2/O:9 and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis 1/O:1 strains isolated from human and non-human sources in the Plateau State of Nigeria. Food Microbiology. 2009;26(8):872–875. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korkeala H. Low occurrence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in clinical, food, and environmental samples: a methodological problem. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2003;16(2):220–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.220-229.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: overview and epidemiologic correlates. Microbes and Infection. 1999;1(4):323–333. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapperud G. Yersinia enterocolitica in food hygiene. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1991;12(1):53–66. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90047-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostroff S. Yersinia as an emerging infection: epidemiologic aspects of Yersiniosis. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;13:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portnoy DA, Martinez RJ. Role of a plasmid in the pathogenicity of Yersinia species. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 1985;118:29–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70586-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brubaker RR. Factors promoting acute and chronic diseases caused by yersiniae. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1991;4(3):309–324. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carniel E. Chromosomal virulence factors of Yersinia: an update. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;13:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornelis GR, Boland A, Boyd AP, et al. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 1998;62(4):1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakajima H, Inoue M, Mori T, Itoh KI, Arakawa E, Watanabe H. Detection and identification of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by an improved polymerase chain reaction method. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1992;30(9):2484–2486. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2484-2486.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Korkeala H. Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2006;47(3):315–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Björkroth J, Hielm S, Korkeala H. Prevalence and characterization of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in pig tonsils from different slaughterhouses. Food Microbiology. 2000;17(1):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyapalle S, Wesley IV, Hurd HS, Reddy PG. Comparison of culture, multiplex, and 5′ nuclease polymerase chain reaction assays for the rapid detection of Yersinia enterocolitica in swine and pork products. Journal of Food Protection. 2001;64(9):1352–1361. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.9.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nesbakken T, Eckner K, Høidal HK, Røtterud OJ. Occurrence of Yersinia enterocolitica and Campylobacter spp. in slaughter pigs and consequences for meat inspection, slaughtering, and dressing procedures. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2003;80(3):231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez PO, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Pallotti A, Rosmini R, Houf K, Korkeala H. Variation in the prevalence of enteropathogenic Yersinia in slaughter pigs from Belgium, Italy, and Spain. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2011;8(3):445–450. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez PO, Mylona S, Drake I, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korkeala H, Corry JEL. Wide variety of bioserotypes of enteropathogenic Yersinia in tonsils of English pigs at slaughter. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2010;139(1-2):64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Stephan R. Prevalence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in pigs slaughtered at a Swiss abattoir. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2007;119(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhaduri S, Wesley IV, Bush EJ. Prevalence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains in pigs in the United States. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(11):7117–7121. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7117-7121.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Cui Z, Wang H, et al. Pathogenic strains of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) belonging to farmers are of the same subtype as pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains isolated from humans and may be a source of human infection in Jiangsu Province, China. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(5):1604–1610. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01789-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vishnubhatla A, Fung DYC, Oberst RD, Hays MP, Nagaraja TG, Flood SJA. Rapid 5' nuclease (TaqMan) assay for detection of virulent strains of Yersinia enterocolitica . Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(9):4131–4135. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.4131-4135.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannessen GS, Kapperud G, Kruse H. Occurrence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in Norwegian pork products determined by a PCR method and a traditional culturing method. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2000;54(1-2):75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(99)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambertz ST, Danielsson-Tham ML. Identification and characterization of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica isolates by PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(7):3674–3681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3674-3681.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grahek-Ogden D, Schimmer B, Cudjoe KS, Nygård K, Kapperud G. Outbreak of Yersinia enterocolitica serogroup O:9 infection and processed pork, Norway. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(5):754–756. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.061062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cocolin L, Comi G. Use of a culture-independent molecular method to study the ecology of Yersinia spp. in food. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2005;105(1):71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakai T, Nakayama A, Hashida M, Yamamoto Y, Takebe H, Imai S. Outbreak of food poisoning by Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O8 in Nara Prefecture: the first case report in Japan. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;58(4):257–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandery M, Stinear T, Kaucner C. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in environmental waters by PCR. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1996;80(3):327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korte T, Korkeala H. Contamination of carcasses, offals, and the environment with yadA-positive Yersinia enterocolitica in a pig slaughterhouse. Journal of Food Protection. 2000;63(1):31–35. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-63.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wauters G. Carriage of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype 3 by pigs as a source of human infection. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1979;5:249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiemann DA. Isolation of toxigenic Yersinia enterocolitica from retail pork products. Journal of Food Protection. 1980;43:360–365. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-43.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle MP, Hugdahl MB, Taylor SL. Isolation of virulent Yersinia enterocolitica from porcine tongues. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1981;42(4):661–666. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.4.661-666.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nesbakken T. Comparison of sampling and isolation procedures for recovery of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3 from the oral cavity of slaughter pigs. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 1985;26(1):127–135. doi: 10.1186/BF03546570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiozawa K, Akiyama M, Sahara K, et al. Pathogenicity of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 3B and 4, serotype O:3 isolates from pork samples and humans. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1987;9:30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrer MG, Otero BM, Figa PC, Prats G. Yersinia enterocolitica infections and pork. The Lancet. 1987;2(8554):p. 334. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90920-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wauters G, Goossens V, Janssens M, Vandepitte J. New enrichment method for isolation of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica serogroup O:3 from pork. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1988;54(4):851–854. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.4.851-854.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Boer E, Nouws JFM. Slaughter pigs and pork as a source of human pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica . International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1991;12(4):375–378. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90151-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karib H, Seeger H. Presence of Yersinia and Campylobacter spp. in foods. Fleischwirtschaft. 1994;74:1104–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Guisti M, de Vito E, Serra A, et al. Occurrence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in slaughtered pigs and pork products. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;13:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Lyhs U, Korte T, Korkeala H. Prevalence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in food samples at retail level in Finland. Archiv fur Lebensmittelhygiene. 2001;52(3):66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Bucher M, Hank C, Stolle A, Korkeala H. High prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica 4:O3 on pig offal in Southern Germany: a slaughtering technique problem. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 2001;24(3):457–463. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nesbakken T, Gondrosen B, Kapperud G. Investigation of Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersinia enterocolitica-like bacteria, and thermotolerant campylobacters in Norwegian pork products. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1985;1(6):311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christensen SG. The Yersinia enterocolitica situation in Denmark. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1987;9:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nesbakken T, Kapperud G, Dommarsnes K, Skurnik M, Hornes E. Comparative study of a DNA hybridisation method and two isolation procedures for detection of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 in naturally contaminated pork products. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1991;57(2):389–394. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.389-394.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai SJ, Chen LH. Occurrence of Yersinia enterocolitica in pork products from northern Taiwan. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1991;12:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Logue CM, Sheridan JJ, Wauters G, Mc Dowell DA, Blair IS. Yersinia spp. and numbers, with particular reference to Y. enterocolitica bio/serotypes, occurring on Irish meat and meat products, and the influence of alkali treatment on their isolation. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1996;33(2-3):257–274. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukushima H, Hoshina K, Itogawa H, Gomyoda M. Introduction into Japan of pathogenic Yersinia through imported pork, beef and fowl. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1997;35(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Hielm S, Korkeala H. High prevalence of yadA-positive Yersinia enterocolitica in pig tongues and minced meat at the retail level. Journal of Food Protection. 1999;62(2):123–127. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurvell B. Zoonotic Yersinia enterocolitica infection: host range, clinical manifestations, and transmission between animals and man. In: Bottone EJ, editor. Yersinia Enterocolitica. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1981. pp. 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiemann DA. Alkatolerance of Yersinia enterocolitica as a basis for selective isolation from food enrichments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1983;46(1):22–27. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.1.22-27.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Devenish JA, Schiemann DA. An abbreviated scheme for identification of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from food enrichments on CIN (cefsulodin-irgasan-novobiocin) agar. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1981;27(9):937–941. doi: 10.1139/m81-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schiemann DA. Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotubercu losis. In: Doyle MP, editor. Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 1989. pp. 601–672. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skurnik M, Nurmi T, Granfors K, Koskela M, Tiilikainen AS. Plasmid associated antibody production against Yersinia enterocolitica in man. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1983;15(2):173–177. doi: 10.3109/inf.1983.15.issue-2.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prpic JK, Robins-Browne RM, Davey RB. Differentiation between virulent and avirulent Yersinia enterocolitica isolates by using congo red agar. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1983;18(3):486–490. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.3.486-490.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhaduri S, Conway LK, Lachica RV. Assay of crystal violet binding for rapid identification of virulent plasmid-bearing clones of Yersinia enterocolitica . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1987;25(6):1039–1042. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.6.1039-1042.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhaduri S, Turner-Jones C, Taylor MM, Lachica RV. Simple assay of calcium dependency for virulent plasmid-bearing clones of Yersinia enterocolitica . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28(4):798–800. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.4.798-800.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Siitonen A, Korkeala H. Sporadic human Yersinia enterocolitica infections caused by bioserotype 4/O:3 originate mainly from pigs. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2006;55(6):747–749. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miliotis MD, Galen JE, Kaper JB, Morris JG., Jr. Development and testing of a synthetic oligonucleotide probe for the detection of pathogenic Yersinia strains. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1989;27(7):1667–1670. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1667-1670.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jagow J, Hill WE. Enumeration by DNA colony hybridization of virulent Yersinia enterocolitica colonies in artificially contaminated food. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1986;51(2):441–443. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.2.441-443.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Durisin MD, Ibrahim A, Griffiths MW. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in milk and pork using a DIG-labelled probe targeted against the yst gene. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1997;37(2-3):103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goverde RLJ, Jansen WH, Brunings HA, Veld JHIV, Mooi FR. Digoxigenin-labelled inv- and ail-probes for the detection and identification of pathogenic Yersinia enterocilitica in clinical specimens and naturally contaminated pig samples. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1993;74(3):301–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kapperud G, Vardund T, Skjerve E, Hornes E, Michaelsen TE. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in foods and water by immunomagnetic separation, nested polymerase chain reactions, and colorimetric detection of amplified DNA. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59(9):2938–2944. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2938-2944.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weagant SD, Jagow JA, Jinneman KC, Omiecinski CJ, Kaysner CA, Hill WE. Development of digoxigenin-labeled PCR amplicon probes for use in the detection and identification of enteropathogenic Yersinia and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from foods. Journal of Food Protection. 1999;62(5):438–443. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.5.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nesbakken T, Kapperud G, Sorum H, Dommarsnes K. Structural variability of 40–50 MDa virulence plasmids from Yersinia enterocolitica . Acta Pathologica Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica—Section B. 1987;95(3):167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1987.tb03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kapperud G, Nesbakken T, Aleksic S, Mollaret HH. Comparison of restriction endonuclease analysis and phenotypic typing methods of differentiation of Yersinia enterocolitica isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28(6):1125–1131. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1125-1131.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rasmussen HN, Rasmussen OF, Andersen JK, Olsen JE. Specific detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by two-step PCR using hot-start and DMSO. Molecular and Cellular Probes. 1994;8(2):99–108. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1994.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andersen JK, Saunders NA. Epidemiological typing of Yersinia enterocolitica by analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms with a cloned ribosomal RNA gene. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1990;32(3):179–187. doi: 10.1099/00222615-32-3-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lobato MJ, Landeras E, González-Hevia MA, Mendoza MC. Genetic heterogeneity of clinical strains of Yersinia enterocolitica traced by ribotyping and relationships between ribotypes, serotypes, and biotypes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36(11):3297–3301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3297-3302.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Najdenski H, Iteman I, Carniel E. Efficient subtyping of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1994;32(12):2913–2920. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2913-2920.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saken E, Roggenkamp A, Aleksic S, Heesemann J. Characterisation of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica serogroups by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of genomic NotI restriction fragments. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1994;41(5):329–338. doi: 10.1099/00222615-41-5-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iteman L, Guiyoule A, Carniel E. Comparison of three molecular methods for typing and subtyping pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1996;45(1):48–56. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-1-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Koch U, Klemm C, Bucher M, Stolle A. Different genotypes of Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3 strains widely distributed in butcher shops in the Munich area. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2004;95(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sachdeva P, Virdi JS. Repetitive elements sequence (REP/ERIC)-PCR based genotyping of clinical and environmental strains of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A reveal existence of limited number of clonal groups. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2004;240(2):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wojciech L, Staroniewicz Z, Jakubczak A, Ugorski M. Typing of Yersinia enterocolitica isolates by ITS profiling, REP- and ERIC-PCR. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series B. 2004;51(5):238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korte T, Korkeala H. Transmission of Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3 to pets via contaminated pork. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2001;32(6):375–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fukushima H, Gomyoda M, Aleksic S, Tsubokura M. Differentiation of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:5,27 strains by phenotypic and molecular techniques. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1993;31(6):1672–1674. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1672-1674.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hayashidani H, Ishiyama Y, Okatani TA, et al. Molecular genetic typing of Yersinia enterocolitica serovar O:8 isolated in Japan. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2003;529:363–365. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48416-1_72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fearnley C, On SLW, Kokotovic B, Manning G, Cheasty T, Newell DG. Application of fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism for comparison of human and animal isolates of Yersinia enterocolitica . Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(9):4960–4965. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.4960-4965.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Hallanvuo S, Korte T, Siitonen A, Korkeala H. Correspondence of genotypes of sporadic Yersinia enterocolitica bioserotype 4/O:3 strains from human and porcine sources. Epidemiology and Infection. 2001;127(1):37–47. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801005611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laukkanen R, Martínez PO, Siekkinen KM, Ranta J, Maijala R, Korkeala H. Transmission of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in the pork production chain from farm to slaughterhouse. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(17):5444–5450. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02664-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laukkanen R, Martínez PO, Siekkinen KM, Ranta J, Maijala R, Korkeala H. Contamination of carcasses with human pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3 originates from pigs infected on farms. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2009;6(6):681–688. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sulakvelidze A, Dalakishvili K, Barry E, et al. Analysis of clinical and environmental Yersinia isolates in the Republic of Georgia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34(9):2325–2327. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2325-2327.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stolk-Engelaar VMM, Hoogkamp-Korstanje JAA. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of gastrointestinal infections by Yersinia enterocolitica in 261 Dutch patients. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;28(6):571–575. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ratnam S, Mercer E, Picco B, Parsons S, Butler R. A nosocomial outbreak of diarrheal disease due to Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:5, biotype 1. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1982;145(2):242–247. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Noble MA, Barteluk RL, Freeman HJ, Subramaniam R, Hudson JB. Clinical significance of virulence-related assay of Yersinia species. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1987;25(5):802–807. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.5.802-807.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seto WH, Lau JTK. Septicaemia due to Yersinia enterocolitica biotype I in Hong Kong. Journal of Infection. 1984;8(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(84)93246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Greenwood MH, Hooper WL. Excretion of Yersinia spp. associated with consumption of pasteurized milk. Epidemiology and Infection. 1990;104(3):345–350. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800047361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McIntyre M, Nnochiri E. A case of hospital-acquired Yersinia enterocolitica gastroenteritis. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1986;7(3):299–301. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(86)90084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cimolai N, Trombley C, Blair GK. Implications of Yersinia enterocolitica biotyping. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1994;70(1):19–21. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Greenwood M, Hooper WL. Human carriage of Yersinia spp. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1987;23(4):345–348. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-4-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Butt HL, Gordon DL, Lee-Archer T, Moritz A, Merrell WH. Relationship between clinical and milk isolates of Yersinia enterocolitica . Pathology. 1991;23(2):153–157. doi: 10.3109/00313029109060816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morris JG, Jr., Prado V, Ferreccio C, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from two cohorts of young children in Santiago, Chile: incidence of and lack of correlation between illness and proposed virulence factors. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1991;29(12):2784–2788. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2784-2788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Onyemelukwe NF. Yersinia enterocolitica as an aetiological agent of childhood diarrhoea in Enugu, Nigeria. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1993;39(9):192–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fenwick SG, McCarthy MD. Yersinia enterocolitica is a common cause of gastroenteritis in Auckland. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1995;108(1003):269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Falcão JP, Falcão DP, Pitondo-Silva A, Malaspina AC, Brocchi M. Molecular typing and virulence markers of Yersinia enterocolitica strains from human, animal and food origins isolated between 1968 and 2000 in Brazil. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2006;55(11):1539–1548. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46733-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rosner BM, Stark K, Werber D. Epidemiology of reported Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Germany, 2001–2008. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:p. 337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. OzFoodNet sites, 1 July to 30 September 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Prpic JK, Robins-Browne RM, Davey RB. In vitro assessment of virulence in Yersinia enterocolitica and related species. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1985;22(1):105–110. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.1.105-110.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tauxe RV, Vandepitte J, Wauters G, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica infections and pork: the missing link. The Lancet. 1987;1(8542):1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ostroff SM, Kapperud G, Hutwagner LC, et al. Sources of sporadic Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Norway: a prospective case-control study. Epidemiology and Infection. 1994;112(1):133–141. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kanazawa Y, Ikemura K, Sasagawa I, Shigeno N. A case of terminal ileitis due to Yersinia pseudotuberculosis . Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1974;48(6):220–228. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.48.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fosse J, Seegers H, Magras C. Foodborne zoonoses due to meat: a quantitative approach for a comparative risk assessment applied to pig slaughtering in Europe. Veterinary Research. 2008;39(1) doi: 10.1051/vetres:2007039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korkeala H. Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2003;529:295–369. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48416-1_56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ackers ML, Schoenfeld S, Markman J, et al. An outbreak of Yersinia enterocolitica O:8 infections associated with pasteurized milk. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;181(5):1834–1837. doi: 10.1086/315436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Swaminathan B, Harmon MC, Mehlman IJ. Yersinia enterocolitica. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1982;52(2):151–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1982.tb04838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lee TS, Lee SW, Seok WS, et al. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility, and virulence factors of Yersinia enterocolitica and related species from ready-to-eat vegetables available in Korea. Journal of Food Protection. 2004;67(6):1123–1127. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Favier GI, Escudero ME, de Guzmán AMS. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from the surface of chicken eggshells obtained in Argentina. Journal of Food Protection. 2005;68(9):1812–1815. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.9.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Berzero R, Volterra L, Chiesa C. Isolation of yersiniae from sewage. Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology. 1991;12:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Christensen SG. Yersinia enterocolitica in Danish pigs. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1980;48(3):377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1980.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cork SC, Marshall RB, Madie P, Fenwick SG. The role of wild birds and the environment in the epidemiology of Yersiniae in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 1995;43(5):169–174. doi: 10.1080/00480169.1995.35883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mafu A, Higgins A, Nadeau M, Cousineau G. The incidence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia enterocolitica in swine carcasses and the slaughterhouse environment. Journal of Food Protection. 1989;52(9):642–645. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-52.9.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sammarco ML, Ripabelli G, Ruberto A, Iannitto G, Grasso GM. Prevalence of Salmonellae, Listeriae, and Yersiniae in the slaughter house environment and on work surfaces, equipment, and workers. Journal of Food Protection. 1997;60:367–371. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nesbakken T. Enumeration of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 from the porcine oral cavity, and its occurrence on cut surfaces of pig carcasses and the environment in a slaughterhouse. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1988;6(4):287–293. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(88)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fransen NG, van den Elzen AMG, Urlings BAP, Bijker PGH. Pathogenic micro-organisms in slaughterhouse sludge—a survey. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 1996;33(2-3):245–256. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Falcão JP, Brocchi M, Proença-Módena JL, Acrani GO, Corrêa EF, Falcão DP. Virulence characteristics and epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersiniae other than Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis isolated from water and sewage. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2004;96(6):1230–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Iwata T, Une Y, Okatani AT, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica serovar O:8 infection in breeding monkeys in Japan. Microbiology and Immunology. 2005;49(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]