Abstract

Myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas represent a heterogeneous group of mesenchymal tumors characterized by a predominantly myxoid matrix, including myxoid liposarcoma (MLS), low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS), extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC), myxofibrosarcoma, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma (MIFS), and myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses have shown that many of these sarcomas are characterized by recurrent chromosomal translocations resulting in highly specific fusion genes (e.g., FUS-DDIT3 in MLS, FUS-CREB3L2 in LGFMS, EWSR1-NR4A3 in EMC, and COL1A1-PDGFB in myxoid DFSP). Moreover, recent molecular analysis has demonstrated a translocation t(1; 10)(p22; q24) resulting in transcriptional upregulation of FGF8 and NPM3 in MIFS. Most recently, the presence of TGFBR3 and MGEA5 rearrangements has been identified in a subset of MIFS. These genetic alterations can be utilized as an adjunct in diagnostically challenging cases. In contrast, most myxofibrosarcomas have complex karyotypes lacking specific genetic alterations. This paper focuses on the cytogenetic and molecular genetic findings of myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas as well as their clinicopathological characteristics.

1. Introduction

Myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas encompass a heterogeneous group of rare tumors characterized by a marked abundance of mucoid/myxoid extracellular matrix. The main clinicopathological entities in this group are myxoid liposarcoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma, and myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans [1–4]. The correct classification of these sarcomas is important because of their distinct biological behaviors and potentially different treatments. However, it is often difficult to set apart many of these sarcomas due to overlapping histological features and lack of a distinct immunohistochemical profile. Moreover, the use of core needle biopsies to diagnose these sarcomas has become increasingly common, and this shift has created additional challenges.

Cytogenetic and molecular genetic assays are routinely used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes in molecular pathology laboratories [5]. Many of myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas are characterized by recurrent chromosomal translocations resulting in highly specific fusion genes [6, 7]. Advances in knowledge of the genetics of these sarcomas are leading to more accurate diagnosis. This paper reviews the cytogenetic and molecular genetic findings in these sarcoma types and their relationship with clinicopathological features. The consistent genetic alterations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chromosomal alterations and related molecular events in myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas.

| Tumor type | Chromosomal alteration | Molecular event | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myxoid/round cell liposarcoma | t(12; 16)(q13; p11) | FUS-DDIT3 | >90% |

| t(12; 22)(q13; q12) | EWSR1-DDIT3 | <5% | |

| Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma | t(7; 16)(q32–34; p11) | FUS-CREB3L2 | >95% |

| t(11; 16)(p11; p11) | FUS-CREB3L1 | <5% | |

| Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma | t(9; 22)(q22; q12) | EWSR1-NR4A3 | 75% |

| t(9; 17)(q22; q11) | TAF15-NR4A3 | 15% | |

| t(9; 15)(q22; q21) | TCF12-NR4A3 | <1% | |

| t(3; 9)(q12; q22) | TFG-NR4A3 | <1% | |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | Complex karyotype | Not known | Not applicable |

| Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma | t(1; 10)(p22; q24) | Deregulation of FGF8 and NPM3 | Not applicable |

| Rearrangement of TGFBR3 and MGEA5 | Not applicable | ||

| Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | t(17; 22)(q22; q13)* | COL1A1-PDGFB | >90% |

*Rearrangement also frequently seen as a ring chromosome.

2. Approaches to the Genetics of Soft-Tissue Sarcomas

Conventional karyotyping is the most comprehensive method for spotting the various translocations and other structural or numerical aberrations. It is dependent on the availability of fresh, sterile tumor tissue, the success of tumor cell growth in culture, and quality of metaphase cell preparations. When dividing cells are not available for cytogenetic studies, molecular approaches such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), or gene expression microarray can be used to evaluate genetic alterations.

FISH is the most helpful method for identifying specific gene rearrangements. It is more adaptable to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues although imprint slides are preferred. Interphase FISH is particularly useful to assess intratumoral genetic heterogeneity as long as adequate combination of probes are used. FISH probes are readily available for a variety of relevant gene targets, including DDIT3 (12q13), FUS (16p11), EWSR1 (22q12), FKHR (13q14), SYT (18q11.2), and ALK (2p23) (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, Ill, USA). It has been realized that FISH is a valuable adjunct in the diagnosis of myxoid soft-tissue tumors [8].

CGH is a method for genome-wide analysis of DNA sequence copy number in a single experiment. It maps the origins of amplified and deleted DNA sequences on normal chromosomes, thereby highlighting regions harboring potential oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. However, CGH cannot detect rearrangements such as balanced translocations or inversions. Recently, a higher resolution version of CGH, so-called array CGH, has been made available. A distinct advantage of array CGH is the ability to directly map the copy number changes to the genome sequence. Similar to array CGH, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array is capable of identifying small regions of chromosomal gains and losses at a high resolution. Also, SNP array can provide information regarding loss of heterozygosity.

RT-PCR is the most sensitive method to detect small numbers of translocation-bearing cells that are mixed within a tissue consisting of largely nonneoplastic cells. Sensitivity levels of 1 in a 100,000 cells are typically achieved. It may be suitable for the detection or monitoring of minimal residual disease [9]. However, the diagnostic success rate is variable and dependent on multiple factors. First, RNA quality may be inadequate because of RNA degradation. The second impediment of this methodology is the high risk of reagent contamination, mainly with PCR products, particularly in small laboratory spaces.

Microarray is a method for genome-wide monitoring of gene expression in a single experiment. A variety of commercial and noncommercial platforms can be used to perform global gene expression profiling. It is hoped that application of this technology will afford increased understanding of sarcoma biology and facilitate the development of new diagnostic markers and therapeutic agents [10–12].

Approximately one-third of all soft issue sarcomas exhibit a nonrandom chromosomal translocation. In addition, a subset of soft-tissue tumors carries specific oncogenic mutations (e.g., KIT or PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumor). FISH and RT-PCR are commonly applied for the detection of specific genetic alterations in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue sarcomas.

3. Myxoid Liposarcoma

The working group of the World Health Organization (WHO) for classification of tumors of soft-tissue and bone combined myxoid and round cell liposarcomas under myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) [13]. MLS is the second most common subtype of liposarcoma, representing approximately one-third of all liposarcomas. MLS occurs predominantly in the deep soft-tissues of lower extremities and has a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life with no gender predilection. Pure MLS is considered low-grade and has a 5-year survival rate of 90% [14]. In contrast, MLS containing a greater than 5% round cell component is considered high-grade and has a worse prognosis. The clinical outcome of multifocal MLS is poor [15]. In contrast to other soft-tissue sarcomas, MLS tends to metastasize to unusual sites such as retroperitoneum, opposite extremity, and bone.

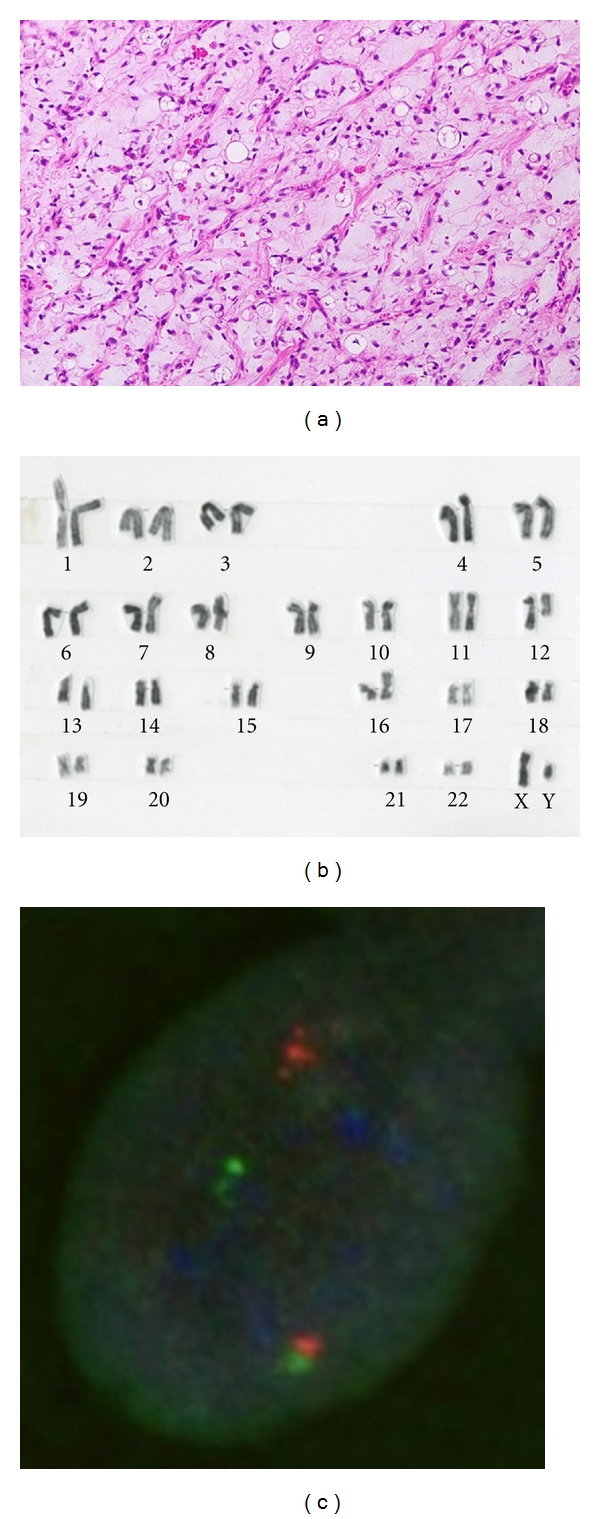

Histologically, pure MLS is composed of primitive mesenchymal cells in a myxoid matrix, often featuring mucinous pools (Figure 1(a)). Lipoblasts are most often univacuolated, small, and tend to cluster around vessels or at the periphery of the lesion. A delicate plexiform capillary vascular network is present and provides an important clue for distinguishing MLS from intramuscular myxoma [16]. A subset of MLS shows histological progression to hypercellular or round cell morphology. The round cell areas are characterized by solid sheets of primitive round cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and a prominent nucleolus. Pure round cell liposarcoma is extremely rare and may be confused with other round cell sarcomas such as Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma.

Figure 1.

(a) Myxoid liposarcoma with a myxoid background containing a delicate arborizing capillary vascular network, small uniform mesenchymal cells, and lipoblasts. (b) G-banded karyotype showing a 12; 16 translocation as the sole aberration. (c) Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis using a DDIT3 (12q13) break-apart probe shows a split of the orange and green signals, indicating a disruption of the DDIT3 locus.

MLS is characterized by a recurrent translocation t(12; 16)(q13; p11) in more than 90% of cases (Figure 1(b)), which fuses the 5′ portion of the FUS gene on chromosome 16 with entire reading frame of the DDIT3 gene on chromosome 12 [17–19]. A small percentage of cases carry a variant translocation t(12; 22)(q13; q12) resulting in an EWSR1-DDIT3 fusion gene [15, 20–28]. The presence of these translocations and molecular alterations is highly sensitive and specific for MLS. Therefore, cytogenetics is an excellent analytic method for the initial workup of a suspected MLS. FISH and RT-PCR can also be used to provide support for the diagnosis of MLS (Figure 1(c)) [8, 29–32]. In addition, several nonrandom secondary alterations have been identified, including 6q deletion, isochromosome 7q10, trisomy 8, and unbalanced 1; 16 translocation [17, 24, 33–35]. Conventional and array CGH studies have shown gains of 8p21–23, 8q, and 13q [36–38].

To date, 12 FUS-DDIT3 and four EWSR1-DDIT3 variants of fusion transcripts have been described in MLS [22, 26, 28, 39, 40]. Most cases of MLS are one of three different FUS-DDIT3 fusion transcript types, including varying portions of FUS. The FUS-DDIT3 fusion transcript type does not appear to have a significant impact on clinical outcome [22, 26]. On the other hand, Suzuki et al. [28] reported that MLS with a type 1 EWSR1-DDIT3 fusion transcript may show more favorable clinical behavior than MLS with other types of fusion transcripts. Interestingly, clinical data suggest that the fusion transcript type may influence response to therapy with trabectedin [41].

Several receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are highly expressed in MLS, including RET, MET, and IGF1R [42, 43]. These RTKs promote cell survival and cell proliferation through the PI3K/AKT and the Ras-Raf-ERK/MAPK pathways [42]. Recently, Barretina et al. [44] demonstrated that mutation of PIK3CA, encoding the catalytic subunit of PI3K, is associated with AKT activation and poor clinical outcome. AKT activation functions as a master switch to generate a plethora of intracellular signals and intracellular responses and is more frequent in the round cell variant [43]. It has also been shown that the NF-κB pathway is highly active in MLS [40]. Moreover, Göransson et al. [45] showed that NF-κB is a major factor controlling IL8 transcription in FUS-DDIT3-expressing cells. NF-κB is an inducible cellular transcription factor that regulates a variety of cellular genes, including those involved in immune regulation, inflammation, cell survival, and cell proliferation. These findings will help to develop new potential therapeutic strategies for MLS patients with advanced disease.

4. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS), first described by Evans [46] in 1987, is a rare but distinctive fibromyxoid variant of fibrosarcoma. It includes the tumor originally designed as hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes [47]. LGFMS occurs primarily in young to middle-aged adults with a male predominance, but this tumor may affect children [48, 49]. LGFMS typically presents as a slowly growing, painless mass in the deep soft-tissues of lower extremities or trunk. Local recurrence and metastatic rates are 9%–21% and 6%–27%, respectively [49, 50]. The overall prognosis for superficial LGFMS appears to be better than that for deep LGFMS [48].

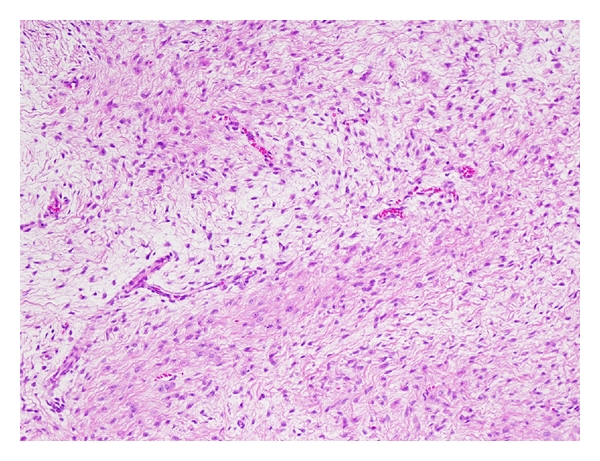

Histologically, LGFMS shows alternating fibrous and myxoid areas with bland spindle-shaped cells arranged in a whorled pattern (Figure 2). Cellularity is variable but generally low and mitoses are scarce. There is often a prominent network of branching capillary-sized blood vessels reminiscent of myxoid liposarcoma. Approximately 40% of cases have giant collagen rosettes characterized by a central zone of eosinophilic collagen surrounded by a palisade of round to oval tumor cells [13]. This variant was originally termed hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes [47]. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and focally for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [48, 50]. Immunostains for S-100 protein, desmin, and CD34 are typically negative.

Figure 2.

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with alternating fibrous and myxoid areas.

LGFMS is characterized by a recurrent balanced translocation t(7; 16)(q34; p11) resulting in an FUS-CREB3L2 fusion gene [50–53]. This same translocation was identified in cases of hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes [54, 55], suggesting a pathogenetic link between these two entities. A small percentage of cases carry a variant translocation t(11; 16)(p11; p11) leading to a fusion of the FUS and CREB3L1 genes [50, 53]. Interestingly, supernumerary ring chromosomes have been observed as the sole anomaly in a subset of LGFMS [52, 56, 57]. FISH and CGH studies have demonstrated that ring chromosomes are composed of material from chromosomes 7 and 16 [56, 57]. Bartuma et al. [57] showed that the FUS-CREB3L2 fusion gene can be present in ring chromosomes.

The breakpoints in the fusion transcripts are mostly at exon 6 or 7 of FUS and exon 5 of CREB3L2 or CREB3L1 [50–53, 58]. CREB3L2 is a member of CREB3 family of transcription factors and contains a basic DNA-binding and leucine zipper dimerization domain, highly similar to that in CREB3L1. Panagopoulos et al. [59] suggested that the FUS-CREB3L2 fusion protein is a more potent transcriptional activator than the native CREB3L2 and may contribute to the pathogenesis of LGFMS through the deregulation of its target genes. The molecular variability of fusion transcripts in LGFMS does not appear to have a significant impact on microscopic appearances or clinical outcome [53].

5. Extraskeletal Myxoid Chondrosarcoma

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is categorized by the WHO as a tumor of uncertain differentiation, because there is a paucity of convincing evidence of cartilaginous differentiation [13]. Most EMCs arise in the deep soft-tissues of the proximal extremities and limb girdles, especially the thigh and popliteal fossa, similar to MLS. EMC has a peak incidence in the fifth and six decades of life with a male predominance. Only a few cases have been encountered in children and adolescents [60–62]. Patients typically present with a slowly growing mass that causes pain or tenderness in approximately one-third of cases [16]. Local recurrence and metastatic rates are 48% and 46%, respectively [61]. EMC has a 10-year survival rate of 63%–88%, but a 10-year disease-free survival is much lower, ranging from 14% to 36% [61, 63–66]. Large tumor size (especially >10 cm), advanced age, and proximal tumor location appear to be poor prognostic factors in EMC [61, 63, 67].

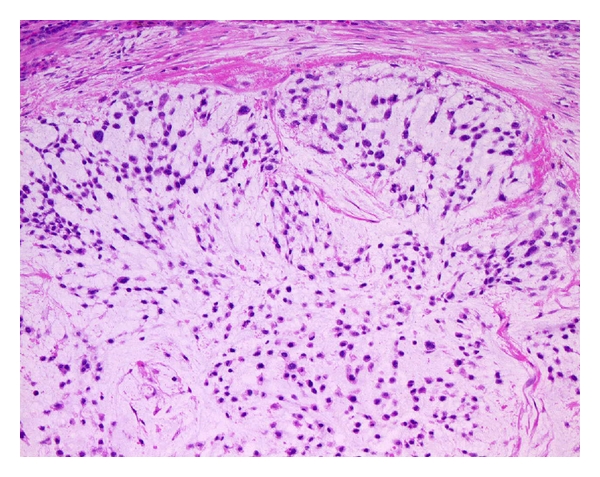

Histologically, EMC is characterized by multinodular growth of a cord-like or lace-like arrangement of round or slightly elongated cells in an abundant myxoid matrix (Figure 3). The tumor cells have small hyperchromatic nuclei and a narrow rim of deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional cells show cytoplasmic vacuolization [16]. Mitotic figures are rare in most cases. In contrast to the bland-looking or low-grade morphology, cellular or high-grade EMC has also been described [61, 68, 69]. Some authors have suggested that the cellular or high-grade EMC is likely to have a worse prognosis than conventional EMC [63, 68, 70] although its prognostic significance has not yet been established [67]. Immunohistochemically, vimentin is the only marker consistently positive in EMC. S-100 protein is expressed in approximately 30% of cases [67], often with focal and weak immunoreactivity. Only a small percentage of cases may show scattered cells that are EMA positive [67]. Recent immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies have demonstrated that some EMCs may have neuroendocrine differentiation [63, 69, 71].

Figure 3.

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with an abundant myxoid matrix containing round or slightly elongated cells with small hyperchromatic nuclei.

EMC is characterized by a recurrent translocation t(9; 22)(q22; q12) in approximately 75% of cases, which fuses the EWSR1 gene on 22q12 with the NR4A3 gene on 9q22 [72–78]. A second variant translocation, t(9; 17)(q22; q11), has been detected in approximately 15% of EMC and results in a TAF15-NR4A3 fusion gene [78–82]. In addition, two additional variant translocations, t(9; 15)(q22; q21) resulting in a TCF12-NR4A3 fusion gene and t(3; 9)(q12; q22) resulting in a TFG-NR4A3 fusion gene, have also been identified, each only in a single case [83, 84]. Because these fusion genes have not yet been described in any other tumor type, they represent useful diagnostic markers. Moreover, several nonrandom secondary alterations have been identified in approximately 50% of cytogenetically analyzed cases, including gain of 1q and trisomy for chromosomes 7, 8, 12, and 19 [77, 78]. The biological significance of these chromosomal alterations remains unknown.

Two main EWSR1-NR4A3 fusion transcript types have been reported for the t(9; 22)(q22; q12) in EMC [69, 77, 78]. The most common fusion transcript contains exon 12 of EWSR1 fused to exon 3 of NR4A3 (type 1), whereas exon 7 of EWSR1 is fused to exon 2 of NR4A3 in the type 2 fusion transcript. In the TAF15-NR4A3 fusion transcript, exon 6 of TAF15 is fused exclusively to exon 3 of NR4A3 [77]. NR4A3 is a member of NR4A subfamily within the nuclear receptor superfamily and contains a zinc finger DNA-binding domain. The EWSR1-NR4A3 fusion protein is thought to function as a potent transcriptional activator for NR4A3-target genes [85, 86]. It has also been shown that the TAF15-NR4A3 fusion protein functions a strong transcriptional activator [87]. It is unclear whether the fusion transcript type is associated with particular morphological features or clinical outcome.

Gene expression profiling studies of EMC have revealed overexpression of the CHI3L1, METTL1, RELB, MYB, NMB, DKK1, DNER, CLCN3, DEF6, NDRG2, and PPARG genes [78, 88, 89]. In addition, several genes encoding neural-neuroendocrine markers have been expressed, including SCG2, NEF3, GFAP, GAD2, ENO2, SYP, CHGA, NEF3, and INSM1 [78, 88]. CHI3L1 encodes a glycoprotein member of the glycosyl hydrolase 18 family, which is secreted by activated chondrocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and synovial cells. Sjögren et al. [78] suggested that CHI3L1 may be useful as a serum marker monitoring disease progression in EMC patients. NMB is a member of bombesin-related peptide family in mammals and a secreted protein involved in stimulation of smooth muscle contraction [90]. Subramanian et al. [88] suggested that NMB may prove to be a serological marker of EMC recurrence. DKK1 encodes a protein that is a member of the dickkopf family. DKK1 is involved in embryonic development through its inhibition of the WNT signaling pathway. Because DKK1 is a secreted protein, it may serve as a prognostic marker for evaluation of EMC. PPARG encodes a member of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subfamily of nuclear receptors. PPARG is known as a regulator of adipocytic differentiation [91]. Interestingly, Filion et al. [89] demonstrated that PPARG is the first direct transcriptional target of the EWSR1-NR4A3 fusion protein. These findings will lead to the development of molecularly targeted therapies for patients with advanced EMC.

6. Myxofibrosarcoma

Myxofibrosarcoma, formerly known as myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), is now defined as a distinct histological entity [13]. It is one of the most common soft-tissue sarcomas in elderly patients. Most myxofibrosarcomas arise in the dermal and subcutaneous tissues of the limbs (especially lower limbs) and limb girdles. Myxofibrosarcoma has a peak incidence in the sixth to eighth decades of life with a slight male predominance. Patients typically present with a slowly growing, painless mass. Recently, an epithelioid variant of myxofibrosarcoma with an aggressive course has been described [92].

Grading of myxofibrosarcoma is somewhat controversial. Myxofibrosarcoma has been subdivided into three or four grades based on the degree of cellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic activity [93, 94]. Local recurrences occur in up to 50% to 60% of cases [93–95], irrespective of histological grade. Whereas low-grade myxofibrosarcomas usually do not metastasize, intermediate and high-grade lesions may develop metastases in approximately 16% to 38% of cases [93–95]. Importantly, low-grade myxofibrosarcomas may become higher grade in subsequent recurrences and acquire metastatic potential. The overall 5-year survival rate is 60%–70% [13].

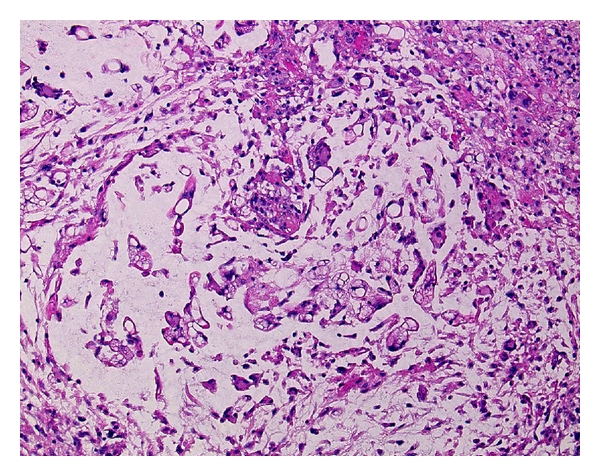

Histologically, myxofibrosarcoma is characterized by multinodular growth of spindle or stellate-shaped cells within variably myxoid stroma containing elongated, curvilinear blood vessels (Figure 4). The tumor cells have slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and mildly atypical, hyperchromatic nuclei. Vacuolated cells with cytoplasmic acid mucin, mimicking lipoblasts, are also seen [13]. Mitotic figures are rare in low-grade lesions. In contrast, high-grade myxofibrosarcomas are composed of solid sheets and fascicles of atypical spindled and pleomorphic tumor cells with hemorrhagic and necrotic areas. Bizarre, multinucleated giant cells are also occasionally found. Mitotic figures, including abnormal mitoses, are frequent. At least focally, however, areas of a lower grade neoplasm with a prominent myxoid matrix are present [13]. Intermediate-grade myxofibrosarcomas are more cellular than low-grade lesions and often contain minute solid areas showing flank pleomorphism. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and occasionally for muscle specific actin and α-smooth muscle actin, suggestive of focal myofibroblastic differentiation.

Figure 4.

Myxofibrosarcoma with a myxoid stroma containing spindle or stellate-shaped cells with mildly atypical, hyperchromatic nuclei.

Data on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of myxofibrosarcoma are difficult to evaluate, because the diagnostic criteria for this tumor have changed with time. In general, myxofibrosarcomas are associated with highly complex karyotypes lacking specific structural aberrations [96–98]. The only recurrent gain involves chromosome 7, whereas losses primarily affect chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 6, 10, 12, 16, 17, and 19 [7]. The presence of ring chromosomes has been described in some cases of low-grade myxofibrosarcoma (or myxoid MFH) [98–100]. In addition, homogeneously staining regions, double minutes, and marker chromosomes have been found. Recently, Willems et al. [98] proposed the concept of progression of myxofibrosarcoma as a multistep genetic process ruled by genetic instability.

A conventional CGH study of 22 myxofibrosarcomas showed gains of 19p and 19q, losses of 1q, 2q, 3p, 4q, 10q, 11q, and 13q, and high-level amplifications of the central regions of chromosome 1, 5p, and 20q [101]. Interestingly, gain of 5p and loss of 4q are not observed in low-grade myxofibrosarcomas as opposed to higher grade neoplasms, suggesting that these aberrations are late events in the oncogenesis of myxofibrosarcoma. In addition, array CGH studies showed gains of 7p21-22, 7q31–35, and 12q15–21 and losses of 10p13-14, 10q25-26, and 13q14–34 [38, 102, 103]. These findings suggest that loss of chromosome 13q is the most frequent genomic imbalance in myxofibrosarcoma, leading to inactivation of the RB pathway.

Recently, Lee et al. [103] reported that MET is expressed in approximately two-third of cases and its overexpression is highly related to deep location, higher grades, and more advanced stages. The authors suggested that MET may represent a target of choice to develop novel therapeutic strategies for myxofibrosarcoma.

A recent gene expression analysis has shown that the WISP2, GPR64, and TNXB genes are upregulated in myxofibrosarcoma compared with other spindle cell and pleomorphic sarcomas [104]. WISP2 encodes a member of the WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein subfamily, which belongs to the connective tissue growth factor family. WISP2 is a secreted protein involved in several important human diseases or conditions that are marked by aberrant cell proliferation and migration [105]. GPR64 is a highly conserved, tissue-specific, seven-transmembrane receptor of the human epididymis [106]. TNXB encodes a member of the tenascin family of extracellular matrix glycoproteins. TNXB is thought to function in matrix maturation during wound healing, and its deficiency is associated with the connective tissue disorder Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [107]. Nakayama et al. [104] suggested that these genes may serve as novel diagnostic markers for myxofibrosarcoma. Most recently, Barretina et al. [44] demonstrated that NF1 is mutated or deleted in 10.5% of myxofibrosarcomas.

7. Myxoinflammatory Fibroblastic Sarcoma

Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma (MIFS), also known as inflammatory myxohyaline tumor of the distal extremities with virocyte or Reed-Sternberg-like cells, is a recently described soft-tissue tumor entity [108, 109]. MIFS occurs predominantly in the subcutaneous tissues of distal extremities and has a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life with no gender predilection. Patients typically present with a slowly growing, painless, ill-defined mass. The preoperative diagnosis in most cases is benign and may include tenosynovitis, ganglion cyst, and giant cell tumor of tendon sheath [13]. Local recurrence and metastatic rates are 31.3% and 3.1%, respectively [110].

Histologically, MIFS is multinodular, poorly delineated, and characterized by a prominent myxoid matrix containing numerous inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils [109]. Germinal centers are occasionally encountered. Neoplastic cells include spindle-shaped and epithelioid cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia, large polygonal and bizarre ganglion-like cells, Reed-Sternberg-like cells with huge inclusion-like nucleoli, and multivacuolated lipoblast-like cells (Figure 5). Hemosiderin deposition may be conspicuous. Mitotic activity is usually low, and necrosis is rarely present. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and focally for CD68 and CD34 [16]. Occasional cases may show scattered cells that stain for cytokeratin or α-smooth muscle actin. Immunostains for S-100 protein, HMB-45, desmin, EMA, leukocyte common antigen, CD15, and CD30 are typically negative.

Figure 5.

Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma with a myxoid background containing spindle-shaped and epithelioid cells, inflammatory cells, and pseudolipoblasts.

Cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic studies have identified the frequent presence of a balanced or unbalanced t(1; 10)(p22; q24) translocation and ring chromosomes containing amplified material from the 3p11-12 region in MIFS [111–113]. A balanced translocation, t(2; 6)(q31; p21.3), has also been described as the sole anomaly in a single case [114]. Most recently, Antonescu et al. [115] demonstrated the presence of TGFBR3 (1p22) and MGEA5 (10q24) gene rearrangements by FISH in a subset of MIFS. It is of interest that the t(1; 10) translocation and these gene rearrangements have also been identified in hemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumor (HFLT) [113, 115–117]. These findings suggest that MIFS and HFLT may represent different morphologic variants of the same entity.

Conventional and array CGH studies showed amplification of 3p11-12 [113, 118]. Notably, Hallor et al. [113] demonstrated that 3p11-12 amplification is associated with an increased expression of VGLL3 and CHMP2B. VGLL3 encodes a protein that is a cofactor of transcription factors of the TEAD family. It has also been shown that VGLL3 is amplified and overexpressed in myxofibrosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, and dedifferentiated liposarcoma [119]. These findings strongly suggest that VGLL3 is the main target of 3p11-12 amplification and this genetic event plays an important role in the development and progression of certain subsets of soft-tissue sarcomas.

A recent gene expression analysis has shown that the FGF8 and NPM3 genes are upregulated in the t(1; 10) -positive tumors compared with tumors without such a translocation [113]. These two genes downstream of MGEA5 have been mapped to 10q24. FGF8, a member of the fibroblast growth factor family, is a secreted heparin-binding protein, which has transforming potential. FGF8 is widely expressed during embryonic development. Overexpression of FGF8 has been shown to increase tumor growth and angiogenesis [120]. Hallor et al. [113] suggested that deregulation of FGF8 may constitute an important event in the development of a subset of MIFS.

8. Myxoid Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare but distinctive variant of DFSP with a prominent myxoid matrix. Clinically, myxoid DFSP is similar to typical DFSP [121–123]. DFSP occurs primarily young to middle-aged adults with a male predominance, but this tumor may affect children, including congenital occurrence [124]. It typically presents as a slowly growing, plaque-like or small nodular lesion. The most common location is the trunk, followed by the limbs and head and neck. Local recurrence and metastatic rates are 0%–52% and 0%–1.7%, respectively [125]. The overall prognosis of typical DFSP is excellent if completely excised with negative microscopic margins. Reimann and Fletcher [122] stated that myxoid DFSP appears to have a similarly good prognosis. Recognition of this DFSP variant is important to avoid misdiagnosis of more or less aggressive myxoid soft-tissue tumors.

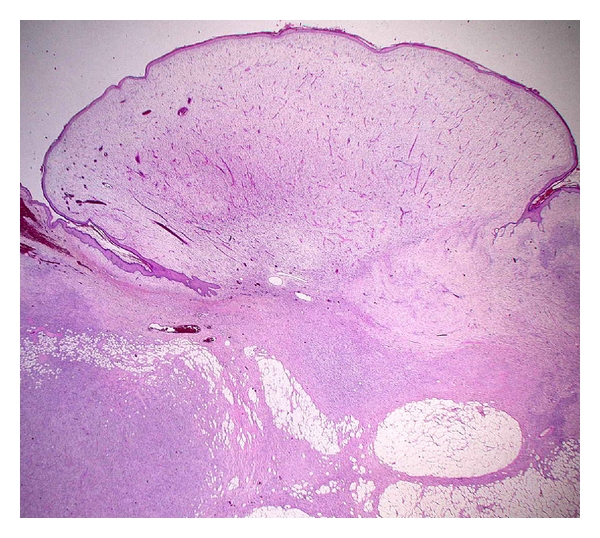

Histologically, myxoid DFSP is characterized by a sheet-like to vaguely lobular proliferation of bland spindle cells in an abundant myxoid stroma (Figure 6). The tumor cells have slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and stellate to oval nuclei with indistinct nucleoli. Branching, thin-walled blood vessels are frequently present. All cases display at least focally a strikingly infiltrative growth pattern, with trapping of subcutaneous adipose tissue in the characteristic honeycomb manner also observed in typical DFSP [122]. Mitotic activity is usually low. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and CD34. Immunostains for S-100 protein, desmin, muscle specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, cytokeratin, and EMA are typically negative. Apolipoprotein D (APOD) has been found to be highly expressed in DFSP and its histological variants [126].

Figure 6.

Typical example of a myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

DFSP is characterized by an unbalanced translocation t(17; 22)(q22; q13), which fuses the COL1A1 gene on 17q21-22 with the PDGFB gene on 22q13 [127–130]. The same molecular event is also seen in supernumerary ring chromosomes derived from the t(17; 22) [129, 130]. Identical genetic changes have also been shown in the histological variants, including myxoid DFSP [123], pigmented DFSP (Bednar tumor) [131], Granular cell DFSP [132], juvenile variant of DFSP (giant cell fibroblastoma) [128], and fibrosarcomatous variant of DFSP [133, 134]. Other rare translocations, including t(X; 7), t(2; 7), t(9; 22), and t(5; 8), have also been described [135–138]. Moreover, several secondary nonrandom alterations have been identified, including trisomy 5 and trisomy 8 [130]. The clinical and biological implications of these chromosomal alterations are virtually unknown.

Conventional and array CGH studies showed gain or high-level amplification of 17q and 22q in most cases [139–141]. DFSP is occasionally misdiagnosed as benign lesions such as dermatofibroma, leading to improper primary management. We suggested that CGH may be a useful diagnostic tool for distinguishing DFSP from dermatofibroma [140]. The presence of gain in 8q was also observed [140–142]. Interestingly, FISH and CGH studies have indicated an association between an increased number of COL1A1-PDGFB genomic copies and fibrosarcomatuos transformation in a subset of DFSP [139, 143, 144]. Most recently, Salgado et al. [145] reported that the majority of DFSP harbor the COL1A1-PDGFB fusion and FISH should be recommended as a routine diagnostic tool.

The breakpoint of PDGFB is remarkably constant (exon 2). In contrast, the COL1A1 breakpoint may occur in any of the exons in the α-helical coding region (exons 6–49). The most frequently rearranged COL1A1 exons are exon 25, 32, and 47 [146]. PDGFB encodes the β chain of platelet-derived growth factor. PDGFB is a potent mitogen for a variety of cells [147]. COL1A1 encodes the pro-α1 chains of type I collagen whose triple helix comprises two α1 chains and one α2 chain. Type I collagen is a major structural protein found in the extracellular matrix of connective tissue such as skin, bone, and tendon. The COL1A1-PDGFB fusion protein is posttranslationally processed to a functional PDGFB, and results in PDGFB-mediated autocrine and/or paracrine activation of PDGFRB [128, 148]. Inhibitors of PDGFRB, such as imatinib mesylate, have been reported to show clinical activity for metastatic or locally advanced DFSP [149–151]. These results support the concept that DFSP cells are dependent on aberrant activation of PDGFRB for cellular proliferation and survival. No correlation between the molecular subtype of COL1A1-PDGFB fusion gene and the clinicopathological features has been established [146, 152].

Gene expression profiling studies of DFSP have revealed overexpression of the PDGFB, PDGFRB, APOD, SPRY2, NRP1, EGR2, and MEOX1 genes [10, 153]. SPRY2 encodes a protein belonging to the sprouty family and is involved in the regulation of the EGF, FGF, and Ras/MAPK signaling pathways. NRP1 is a membrane-bound coreceptor to a tyrosine kinase receptor for both vascular endothelial growth factor and semaphorin family members and plays a role in angiogenesis, cell survival, migration, and invasion. EGR2 is a transcription factor with three tandem C2H2-type zinc fingers and plays a role in the PTEN-induced apoptotic pathway [154]. MEOX1 has been mapped to 17q21 and encodes a member of a subfamily of nonclustered, diverged, antennapedia—like homeobox—containing genes. The homeobox genes are involved in early embryonic development and the determination of cell fate. Linn et al. [153] proposed the possibility that DFSP are derived from early embryonic mesenchymal cells.

9. Conclusions

It is important to be familiar with the clinicopathological and molecular genetic features of myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas for their accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. In our experience, FISH is a valuable ancillary diagnostic tool for these sarcomas, especially on limited tissue samples. Novel diagnostic and/or prognostic molecular markers as well as promising therapeutic targets have gradually been recognized. In the future, treatment decisions and prognosis assessment for myxoid soft-tissue sarcomas will increasingly be based on a combination of histological criteria and molecular identification of genetic alterations indicative of biological properties.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Kaibara Morikazu Medical Science Promotion Foundation, Japan Orthopaedics and Traumatology Foundation, Fukuoka Cancer Society, Clinical Research Foundation, and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (21791424) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PCW, Fletcher CDM. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35(4):291–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willems SM, Schrage YM, Baelde JJ, et al. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue: the so-called myxoid extracellular matrix is heterogeneous in composition. Histopathology. 2008;52(4):465–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.02967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willems SM, Van Remoortere A, Van Zeijl R, Deelder AM, McDonnell LA, Hogendoorn PC. Imaging mass spectrometry of myxoid sarcomas identifies proteins and lipids specific to tumour type and grade, and reveals biochemical intratumour heterogeneity. Journal of Pathology. 2010;222(4):400–409. doi: 10.1002/path.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willems SM, Wiweger M, van Roggen JFG, Hogendoorn PCW. Running GAGs: myxoid matrix in tumor pathology revisited: what’s in it for the pathologist. Virchows Archiv. 2010;456(2):181–192. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0822-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridge JA. Advantages and limitations of cytogenetic, molecular cytogenetic, and molecular diagnostic testing in mesenchymal neoplasms. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2008;13(3):273–282. doi: 10.1007/s00776-007-1215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki H, Nabeshima K, Nishio J, et al. Pathology of soft-tissue tumors: daily diagnosis, molecular cytogenetics and experimental approach: review Article. Pathology International. 2009;59(8):501–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertens F, Panagopoulos I, Mandahl N. Genomic characteristics of soft tissue sarcomas. Virchows Archiv. 2010;456(2):129–139. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downs-Kelly E, Goldblum JR, Patel RM, et al. The utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in the diagnosis of myxoid soft tissue neoplasms. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2008;32(1):8–13. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181578d5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willeke F, Sturm JW. Minimal residual disease in soft-tissue sarcomas. Seminars in Surgical Oncology. 2001;20(4):294–303. doi: 10.1002/ssu.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baird K, Davis S, Antonescu CR, et al. Gene expression profiling of human sarcomas: insights into sarcoma biology. Cancer Research. 2005;65(20):9226–9235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen TO. Microarray analysis of sarcomas. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2006;13(4):166–173. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AH, West RB, van de Rijn M. Gene expression profiling for the investigation of soft tissue sarcoma pathogenesis and the identification of diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers. Virchows Archiv. 2010;456(2):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0774-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Nakashima H, Ishiguro N. Clinicopathologic prognostic factors of pure myxoid liposarcoma of the extremities and trunk wall. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2010;468(11):3041–3046. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1396-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonescu CR, Elahi A, Healey JH, et al. Monoclonality of multifocal myxoid liposarcoma: confirmation by analysis of TLS-CHOP or EWS-CHOP rearrangements. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(7):2788–2793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Mosby; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandberg AA. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: liposarcoma. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2004;155(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conyers R, Young S, Thomas DM. Liposarcoma: molecular genetics and therapeutics. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/483154. Article ID 483154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishio J. Contributions of cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics to the diagnosis of adipocytic tumors. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2011;2011:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/524067. Article ID 524067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panagopoulos I, Höglund M, Mertens F, Mandahl N, Mitelman F, Åman P. Fusion of the EWS and CHOP genes in myxoid liposarcoma. Oncogene. 1996;12(3):489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dal Cin P, Sciot R, Panagopoulos I, et al. Additional evidence of a variant translocation t(12;22) with EWS/CHOP fusion in myxoid liposarcoma: clinicopathological features. Journal of Pathology. 1997;182(4):437–441. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199708)182:4<437::AID-PATH882>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonescu CR, Tschernyavsky SJ, Decuseara R, et al. Prognostic impact of P53 status, TLS-CHOP fusion transcript structure, and histological grade in myxoid liposarcoma: a molecular and clinicopathologic study of 82 cases. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7(12):3977–3987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosaka T, Nakashima Y, Kusuzaki K, et al. A novel type of EWS-CHOP fusion gene in two cases of myxoid liposarcoma. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2002;4(3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60698-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birch NC, Antonescu CR, Nelson M, et al. Inconspicuous insertion 22;12 in myxoid/round cell liposarcoma accompanied by the secondary structural abnormality der(16)t(1;16) Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2003;5(3):191–194. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60472-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsui Y, Ueda T, Kubo T, et al. A novel type of EWS-CHOP fusion gene in myxoid liposarcoma. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;348(2):437–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bode-Lesniewska B, Frigerio S, Exner U, Abdou MT, Moch H, Zimmermann DR. Relevance of translocation type in myxoid liposarcoma and identification of a novel EWSR1-DDIT3 fusion. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2007;46(11):961–971. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alaggio R, Coffin CM, Weiss SW, et al. Liposarcomas in young patients: a study of 82 cases occurring in patients younger than 22 years of age. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2009;33(5):645–658. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181963c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki K, Matsui Y, Endo K, et al. Myxoid liposarcoma with EWS—CHOP type 1 fusion gene. Anticancer Research. 2010;30(11):4679–4683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanas MR, Goldblum JR. Fluorescence in situ hybridization in the diagnosis of soft tissue neoplasms: a review. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2009;16(6):383–391. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanas MR, Rubin BP, Tubbs RR, Billings SD, Downs-Kelly E, Goldblum JR. Utilization of fluorescence in situ hybridization in the diagnosis of 230 mesenchymal neoplasms: an institutional experience. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2010;134(12):1797–1803. doi: 10.5858/2009-0571-OAR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thway K, Rockcliffe S, Gonzalez D, et al. Utility of sarcoma-specific fusion gene analysis in paraffin-embedded material for routine diagnosis at a specialist centre. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2010;63(6):508–512. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.076133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonescu CR, Elahi A, Humphrey M, et al. Specificity of TLS-CHOP rearrangement for classic myxoid/round cell liposarcoma: absence in predominantly myxoid well-differentiated liposarcomas. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2000;2(3):132–138. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60628-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sreekantaiah C, Karakousis CP, Leong SPL, Sandberg AA. Trisomy 8 as a nonrandom secondary change in myxoid liposarcoma. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1991;51(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(91)90132-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibas Z, Miettinen M, Limon J, et al. Cytogenetic and immunohistochemical profile of myxoid liposarcoma. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1995;103(1):20–26. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mrozek K, Bloomfield CD. Der(16)t(1;16) is a secondary chromosome aberration in at least eighteen different types of human cancer. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 1998;23(1):78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parente F, Grosgeorge J, Coindre JM, Terrier P, Vilain O, Turc-Carel C. Comparative genomic hybridization reveals novel chromosome deletions in 90 primary soft tissue tumors. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1999;115(2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt H, Bartel F, Kappler M, et al. Gains of 13q are correlated with a poor prognosis in liposarcoma. Modern Pathology. 2005;18(5):638–644. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohguri T, Hisaoka M, Kawauchi S, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of myxoid liposarcoma and myxofibrosarcoma by array-based comparative genomic hybridisation. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2006;59(9):978–983. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.034942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powers MP, Wang WL, Hernandez VS, et al. Detection of myxoid liposarcoma-associated FUS-DDIT3 rearrangement variants including a newly identified breakpoint using an optimized RT-PCR assay. Modern Pathology. 2010;23(10):1307–1315. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willems SM, Schrage YM, Bruijn IHB, Szuhai K, Hogendoorn PCW, Bovée JVMG. Kinome profiling of myxoid liposarcoma reveals NF-kappaB-pathway kinase activity and Casein Kinase II inhibition as a potential treatment option. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 257 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grosso F, Jones RL, Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy of trabectedin (ecteinascidin-743) in advanced pretreated myxoid liposarcomas: a retrospective study. The Lancet Oncology. 2007;8(7):595–602. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng H, Dodge J, Mehl E, et al. Validation of immature adipogenic status and identification of prognostic biomarkers in myxoid liposarcoma using tissue microarrays. Human Pathology. 2009;40(9):1244–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negri T, Virdis E, Brich S, et al. Functional mapping of receptor tyrosine kinases in myxoid liposarcoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(14):3581–3593. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S, et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):715–721. doi: 10.1038/ng.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Göransson M, Andersson MK, Forni C, et al. The myxoid liposarcoma FUS-DDIT3 fusion oncoprotein deregulates NF-κB target genes by interaction with NFKBIZ. Oncogene. 2009;28(2):270–278. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans HL. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. A report of two metastasizing neoplasms having a deceptively benign appearance. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1987;88(5):615–619. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/88.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lane KL, Shannon RJ, Weiss SW. Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: a distinctive tumor closely resembling low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1997;21(12):1481–1488. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billings SD, Giblen G, Fanburg-Smith JC. Superficial low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (Evans tumor): a clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases with a unique observation in the pediatric population. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2005;29(2):204–210. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146014.22624.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folpe AL, Lane KL, Paull G, Weiss SW. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: a clinicopathologic study of 73 cases supporting their identity and assessing the impact of high-grade areas. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000;24(10):1353–1360. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guillou L, Benhattar J, Gengler C, et al. Translocation-positive low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of a series expanding the morphologic spectrum and suggesting potential relationship to sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma—a study from the French sarcoma group. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2007;31(9):1387–1402. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180321959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storlazzi CT, Mertens F, Nascimento A, et al. Fusion of the FUS and BBF2H7 genes in low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(18):2349–2358. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panagopoulos I, Storlazzi CT, Fletcher CDM, et al. The chimeric FUS/CREB3L2 gene is specific for low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2004;40(3):218–228. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mertens F, Fletcher CDM, Antonescu CR, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular genetic characterization of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and cloning of a novel FUS/CREB3L1 fusion gene. Laboratory Investigation. 2005;85(3):408–415. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bejarano PA, Padhya TA, Smith R, Blough R, Devitt JJ, Gluckman L. Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes—a soft tissue tumor with mesenchymal and neuroendocrine features: an immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and cytogenetic analysis. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2000;124(8):1179–1184. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1179-HSCTWG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reid R, de Silva MVC, Paterson L, Ryan E, Fisher C. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes share a common t(7;16)(q34;p11) translocation. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2003;27(9):1229–1236. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mezzelani A, Sozzi G, Nessling M, et al. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: further low-grade soft tissue malignancy characterized by a ring chromosome. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2000;122(2):144–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bartuma H, Möller E, Collin A, et al. Fusion of the FUS and CREB3L2 genes in a supernumerary ring chromosome in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2010;199(2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M, Shimajiri S, et al. Molecular detection of FUS-CREB3L2 fusion transcripts in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2006;30(9):1077–1084. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209830.24230.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panagopoulos I, Möller E, Dahlén A, et al. Characterization of the native CREB3L2 transcription factor and the FUS/CREB3L2 chimera. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2007;46(2):181–191. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hachitanda Y, Tsuneyoshi M, Daimaru Y, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in young children. Cancer. 1988;61(12):2521–2526. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880615)61:12<2521::aid-cncr2820611222>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meis-Kindblom JM, Bergh P, Gunterberg B, Kindblom LG. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a reappraisal of its morphologic spectrum and prognostic factors based on 117 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1999;23(6):636–650. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199906000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yi JW, Park YK, Choi YM, Hong HP, Chang SG. Bulbous urethra involved in perineal extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in a child. International Journal of Urology. 2004;11(6):436–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oliveira AM, Sebo TJ, McGrory JE, Gaffey TA, Rock MG, Nascimento AG. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ploidy analysis of 23 cases. Modern Pathology. 2000;13(8):900–908. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGrory JE, Rock MG, Nascimento AG, Oliveira AM. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2001;(382):185–190. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawaguchi S, Wada T, Nagoya S, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a multi-institutional study of 42 cases in Japan. Cancer. 2003;97(5):1285–1292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drilon AD, Popat S, Bhuchar G, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a retrospective review from 2 referral centers emphasizing long-term outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3364–3371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hisaoka M, Hashimoto H. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: updated clinicopathological and molecular genetic characteristics. Pathology International. 2005;55(8):453–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lucas DR, Fletcher CDM, Adsay NV, Zalupski MM. High-grade extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a high-grade epithelioid malignancy. Histopathology. 1999;35(3):201–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okamoto S, Hisaoka M, Ishida T, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 18 cases. Human Pathology. 2001;32(10):1116–1124. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.28226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oshiro Y, Shiratsuchi H, Tamiya S, Oda Y, Toyoshima S, Tsuneyoshi M. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with rhabdoid features, with special reference to its aggressive behavior. International Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000;8(2):145–152. doi: 10.1177/106689690000800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goh YW, Spagnolo DV, Platten M, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a light microscopic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and immuno-ultrastructural study indicating neuroendocrine differentiation. Histopathology. 2001;39(5):514–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sciot R, Dal Cin P, Fletcher C, et al. T(9;22)(q22-31;q11-12) is a consistent marker of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: evaluation of three cases. Modern Pathology. 1995;8(7):765–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stenman G, Andersson H, Mandahl N, Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Translocation t(9;22)(q22;q12) is a primary cytogenetic abnormality in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. International Journal of Cancer. 1995;62(4):398–402. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Labelle Y, Zucman J, Stenman G, et al. Oncogenic conversion of a novel orphan nuclear receptor by chromosome translocation. Human Molecular Genetics. 1995;4(12):2219–2226. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.12.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark J, Benjamin H, Gill S, et al. Fusion of the EWS gene to CHN, a member of the steroid/thyroid receptor gene superfamily, in a human myxoid chondrosarcoma. Oncogene. 1996;12(2):229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brody RI, Ueda T, Hamelin A, et al. Molecular analysis of the fusion of EWS to an orphan nuclear receptor gene in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;150(3):1049–1058. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of the EWS/CHN and RBP56/CHN fusion genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2002;35(4):340–352. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sjögren H, Meis-Kindblom JM, Örndal C, et al. Studies on the molecular pathogenesis of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma—cytogenetic, molecular genetic, and cDNA microarray analyses. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162(3):781–792. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63875-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Panagopoulos I, Mencinger M, Dietrich CU, et al. Fusion of the RBP56 and CHN genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas with translocation t(9;17)(q22;q11) Oncogene. 1999;18(52):7594–7598. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Attwooll C, Tariq M, Harris M, Coyne JD, Telford N, Varley JM. Identification of a novel fusion gene involving hTAF(II)68 and CHN from a t(9;17)(q22;q11.2) translocation in an extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Oncogene. 1999;18(52):7599–7601. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sjögren H, Meis-Kindblom J, Kindblom LG, Åman P, Stenman G. Fusion of the EWS-related gene TAF2N to TEC in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Cancer Research. 1999;59(20):5064–5067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harris M, Coyne J, Tariq M, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: a pathologic, cytogenetic, and molecular study of a case with a novel translocation t(9;17)(q22;q11.2) American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000;24(7):1020–1026. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sjögren H, Wedell B, Meis Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Stenman G. Fusion of the NH2-terminal domain of the basic helix-loop-helix protein TCF12 to TEC in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with translocation t(9;15)(q22;q21) Cancer Research. 2000;60(24):6832–6835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hisaoka M, Ishida T, Imamura T, Hashimoto H. TFG is a novel fusion partner of NOR1 in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2004;40(4):325–328. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Labelle Y, Bussières J, Courjal F, Goldring MB. The EWS/TEC fusion protein encoded by the t(9;22) chromosomal translocation in human chondrosarcomas is a highly potent transcriptional activator. Oncogene. 1999;18(21):3303–3308. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohkura N, Nagamura Y, Tsukada T. Differential transactivation by orphan nuclear receptor NOR1 and its fusion gene product EWS/NOR1: possible involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase I, PARP-1. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2008;105(3):785–800. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim S, Hye JL, Hee JJ, Kim J. The hTAFII68-TEC fusion protein functions as a strong transcriptional activator. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;122(11):2446–2453. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Subramanian S, West RB, Marinelli RJ, et al. The gene expression profile of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Journal of Pathology. 2005;206(4):433–444. doi: 10.1002/path.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Filion C, Motoi T, Olshen AB, et al. The EWSRI/NR4A3 fusion protein of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma activates the PPARG nuclear receptor gene. Journal of Pathology. 2009;217(1):83–93. doi: 10.1002/path.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ohki-Hamazaki H. Neuromedin B. Progress in Neurobiology. 2000;62(3):297–312. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ . Cell. 1995;83(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nascimento AF, Bertoni F, Fletcher CDM. Epithelioid variant of myxofibrosarcoma: expanding the clinicomorphologic spectrum of myxofibrosarcoma in a series of 17 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2007;31(1):99–105. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213379.94547.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Merck C, Angervall L, Kindblom LG, Odén A. Myxofibrosarcoma. A malignant soft tissue tumor of fibroblastic-histiocytic origin. A clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 110 cases using multivariate analysis. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica—Supplement. 1983;282:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mentzel T, Calonje E, Wadden C, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 75 cases with emphasis on the low-grade variant. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1996;20(4):391–405. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang HY, Lal P, Qin J, Brennan MF, Antonescu CR. Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 49 cases treated at a single institution with simultaneous assessment of the efficacy of 3-tier and 4-tier grading systems. Human Pathology. 2004;35(5):612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mertens F, Fletcher CDM, Dal Cin P, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of 46 pleomorphic soft tissue sarcomas and correlation with morphologic and clinical features: a report of the champ study group. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 1998;22(1):16–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199805)22:1<16::aid-gcc3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kawashima H, Ogose A, Gu W, et al. Establishment and characterization of a novel myxofibrosarcoma cell line. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2005;161(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Willems SM, Debiec-Rychter M, Szuhai K, Hogendoorn PCW, Sciot R. Local recurrence of myxofibrosarcoma is associated with increase in tumour grade and cytogenetic aberrations, suggesting a multistep tumour progression model. Modern Pathology. 2006;19(3):407–416. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meloni-Ehrig AM, Chen Z, Guan XY, et al. Identification of a ring chromosome in a myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma with chromosome microdissection and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1999;109(1):81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nilsson M, Meza-Zepeda LA, Mertens F, Forus A, Myklebost O, Mandahl N. Amplification of chromosome 1 sequences in lipomatous tumors and other sarcomas. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;109(3):363–369. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Idbaih A, Coindre JM, Derré J, et al. Myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma and pleomorphic liposarcoma share very similar genomic imbalances. Laboratory Investigation. 2005;85(2):176–181. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kresse SH, Ohnstad HO, Bjerkehagen B, Myklebost O, Meza-Zepeda LA. DNA copy number changes in human malignant fibrous histiocytomas by array comparative genomic hybridisation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11, article e15378) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee JC, Li CF, Fang FM, et al. Prognostic implication of MET overexpression in myxofibrosarcomas: an integrative array comparative genomic hybridization, real-time quantitative PCR, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemical analysis. Modern Pathology. 2010;23(10):1379–1392. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nakayama R, Nemoto T, Takahashi H, et al. Gene expression analysis of soft tissue sarcomas: characterization and reclassification of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Modern Pathology. 2007;20(7):749–759. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Russo JW, Castellot JJ. CCN5: biology and pathophysiology. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling. 2010;4(3):119–130. doi: 10.1007/s12079-010-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Obermann H, Samalecos A, Osterhoff C, Schröder B, Heller R, Kirchhoff C. HE6, a two-subunit heptahelical receptor associated with apical membranes of efferent and epididymal duct epithelia. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2003;64(1):13–26. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Burch GH, Gong Y, Liu W, et al. Tenascin-X deficiency is associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Nature Genetics. 1997;17(1):104–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Montgomery EA, Devaney KO, Giordano TJ, Weiss SW. Inflammatory myxohyaline tumor of distal extremities with virocyte or Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a distinctive lesion with features simulating inflammatory conditions, Hodgkin’s disease, and various sarcomas. Modern Pathology. 1998;11(4):384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1998;22(8):911–924. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tejwani A, Kobayashi W, Chen YLE, et al. Management of acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5733–5739. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lambert I, Debiec-Rychter M, Guelinckx P, Hagemeijer A, Sciot R. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma with unique clonal chromosomal changes. Virchows Archiv. 2001;438(5):509–512. doi: 10.1007/s004280000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mansoor A, Fidda N, Himoe E, Payne M, Lawce H, Magenis RE. Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma with complex supernumerary ring chromosomes composed of chromosome 3 segments. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2004;152(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hallor KH, Sciot R, Staaf J, et al. Two genetic pathways, t(l;I0) and amplification of 3pll -12, in myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma, haemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumour, and morphologically similar lesions. Journal of Pathology. 2009;217(5):716–727. doi: 10.1002/path.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ida CM, Rolig KA, Hulshizer RL, et al. Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma showing t(2;6)(q31;p21.3) as a sole cytogenetic abnormality. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2007;177(2):139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Consistent t(1;10) abnormality in both myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma (MIFS) and hemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumor (HFLT) Modern Pathology. 2011;24(supplement 1):p. 9A. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wettach GR, Boyd LJ, Lawce HJ, Magenis RE, Mansoor A. Cytogenetic analysis of a hemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumor. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2008;182(2):140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Elco CP, Mariño-Enríquez A, Abraham JA, Dal Cin P, Hornick JL. Hybrid myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma/hemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumor: report of a case providing further evidence for a pathogenetic link. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2010;34(11):1723–1727. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f17d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Baumhoer D, Glatz K, Schulten HJ, et al. Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: investigations by comparative genomic hybridization of two cases and review of the literature. Virchows Archiv. 2007;451(5):923–928. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Pérot G, Chibon F, et al. YAP1 and VGLL3, encoding two cofactors of TEAD transcription factors, are amplified and overexpressed in a subset of soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2010;49(12):1161–1171. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mattila MM, Härkönen PL. Role of fibroblast growth factor 8 in growth and progression of hormonal cancer. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2007;18(3-4):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Frierson HF, Cooper PH. Myxoid variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1983;7(5):445–450. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reimann JDR, Fletcher CDM. Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a rare variant analyzed in a series of 23 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2007;31(9):1371–1377. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802ff7e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mentzel T, Schärer L, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of eight cases. American Journal of Dermatopathology. 2007;29(5):443–448. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318145413c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Maire G, Fraitag S, Galmiche L, et al. A clinical, histologic, and molecular study of 9 cases of congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Archives of Dermatology. 2007;143(2):203–210. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fiore M, Miceli R, Mussi C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated at a single institution: a surgical disease with a high cure rate. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(30):7669–7675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.West RB, Harvell J, Linn SC, et al. Apo D in soft tissue tumors: a novel marker for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2004;28(8):1063–1069. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126857.86186.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pedeutour F, Simon MP, Minoletti F, et al. Translocation, t(17;22)(q22;q13), in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a new tumor-associated chromosome rearrangement. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 1996;72(2-3):171–174. doi: 10.1159/000134178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Simon MP, Pedeutour F, Sirvent N, et al. Deregulation of the platelet-derived growth factor B-chain gene via fusion with collagen gene COL1A1 in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and giant-cell fibroblastoma. Nature Genetics. 1997;15(1):95–98. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sandberg AA, Bridge JA. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and giant cell fibroblastoma. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2003;140(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00848-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sirvent N, Maire G, Pedeutour F. Genetics of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans family of tumors: from ring chromosomes to tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2003;37(1):1–19. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Ishiguro M, et al. Supernumerary ring chromosome in a Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans) is composed of interspersed sequences from chromosomes 17 and 22: a fluorescence in situ hybridization and comparative genomic hybridization analysis. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2001;30(3):305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Maire G, Pédeutour F, Coindre JM. COL1A1-PDGFB gene fusion demonstrates a common histogenetic origin for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and its granular cell variant. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2002;26(7):932–937. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang J, Morimitsu Y, Okamoto S, et al. COL1A1-PDGFB fusion transcripts in fibrosarcomatous areas of six dermatofibrosarcomas protuberans. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2000;2(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60614-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mahajan H, Sharma R, Darmanian A, Peters GB. Fibrosarcomatous variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans showing COL1A1-PDGFB gene fusion, detected using a novel and disease-specific RT-PCR protocol. Pathology. 2010;42(5):488–491. doi: 10.3109/00313025.2010.494290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Craver RD, Correa H, Kao Y, Van Brunt T. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with 46,XY,t(X;7) abnormality in a child. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1995;80(1):75–77. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)93814-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sinovic J, Bridge JA. Translocation (2;17) in recurrent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans [1] Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1994;75(2):156–157. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sonobe H, Furihata M, Iwata J, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans harboring t(9;22)(q32;q12.2) Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1999;110(1):14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bianchini L, Maire G, Guillot B, et al. Complex t(5;8) involving the CSPG2 and PTK2B genes in a case of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans without the COL1A1-PDGFB fusion. Virchows Archiv. 2008;452(6):689–696. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kiuru-Kuhlefelt S, El-Rifai W, Fanburg-Smith J, Kere J, Miettinen M, Knuutila S. Concomitant DNA copy number amplification at 17q and 22q in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 2001;92(3-4):192–195. doi: 10.1159/000056901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Ohjimi Y, et al. Overrepresentation of 17q22∼qter and 22q13 in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans but not in dermatofibromaa comparative genomic hybridization study. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2002;132(2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kaur S, Vauhkonen H, Böhling T, Mertens F, Mandahl N, Knuutila S. Gene copy number changes in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans—a fine-resolution study using array comparative genomic hybridization. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2006;115(3-4):283–288. doi: 10.1159/000095925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Ohjimi Y, et al. Supernumerary ring chromosomes in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may contain sequences from 8q11.2∼qter and 17q21∼qter: a combined cytogenetic and comparative genomic hybridization study. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2001;129(2):102–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Abbott JJ, Erickson-Johnson M, Wang X, Nascimento AG, Oliveira AM. Gains of COL1A1-PDGFB genomic copies occur in fibrosarcomatous transformation of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Modern Pathology. 2006;19(11):1512–1518. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Segura S, Salgado R, Toll A, et al. Identification of t(17;22)(q22;q13) (COL1A1/PDGFB) in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans by fluorescence in situ hybridization in paraffin-embedded tissue microarrays. Human Pathology. 2011;42(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Salgado R, Llombart B, M. Pujol R, et al. Molecular diagnosis of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comparison between reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization methodologies. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2011;50(7):510–517. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Giacchero D, Maire G, Nuin PAS, et al. No correlation between the molecular subtype of COL1A1-PDGFB fusion gene and the clinico-histopathological features of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130(3):904–907. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Heldin CH, Östman A, Rönnstrand L. Signal transduction via platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1378(1):F79–F113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shimizu A, O’Brien KP, Sjöblom T, et al. The dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans-associated collagen type Iα1/platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B-chain fusion gene generates a transforming protein that is processed to functional PDGF-BB. Cancer Research. 1999;59(15):3719–3723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Maki RG, Awan RA, Dixon RH, Jhanwar S, Antonescu CR. Differential sensitivity to imatinib of 2 patients with metastatic sarcoma arising from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. International Journal of Cancer. 2002;100(6):623–626. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(10):1772–1779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kérob D, Porcher R, Vérola O, et al. Imatinib mesylate as a preoperative therapy in dermatofibrosarcoma: results of a multicenter phase II study on 25 patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(12):3288–3295. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Llombart B, Sanmartín O, López-Guerrero JA, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinical, pathological, and genetic (COL1A1-PDGFB) study with therapeutic implications. Histopathology. 2009;54(7):860–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]