Abstract

Dopamine is the most intensely studied monoaminergic neurotransmitter. Dopaminergic neurotransmission plays an important role in regulating several aspects of basic brain function, including motor, behavior, motivation, and working memory. To date, there are numerous positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radiotracers available for targeting different steps in the process of dopaminergic neurotransmission, which permits us to quantify dopaminergic activity in the living human brain. Degeneration of the nigrostriatal dopamine system causes Parkinson's disease (PD) and related Parkinsonism. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that has been classically associated with the reinforcing effects of drug abuse. Abnormalities within the dopamine system in the brain are involved in the pathophysiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Dopamine receptors play an important role in schizophrenia and the effect of neuroleptics is through blockage of dopamine D2 receptors. This review will concentrate on the radiotracers that have been developed for imaging dopaminergic neurons, describe the clinical aspects in the assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders, and suggest future directions in the diagnosis and management of such disorders.

1. Introduction

Neuropsychiatric disorders cause severe human suffering and are becoming a major socioeconomic burden to modern society. The rapid development of noninvasive tools for imaging human brains will improve our understanding of complex brain functions and provide more insight into the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuroimaging techniques currently utilized in neuropsychiatric disorders include a variety of modalities, such as ultrasound, X-rays, computed tomography (CT), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and nuclear medicine imaging [1].

The interactions between transporters/receptors and neurotransmitters play a key role in the diagnosis and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. In contrast with conventional diagnostic imaging procedures, which simply provide anatomical or structural pictures of organs and tissues, nuclear medicine imaging is the only tool to visualize the distribution, density, and activity of neurotransmitters, receptors, or transporters in the brain. Nuclear medicine imaging involves the administration of radioactively labeled tracers, which decay over time by emitting gamma rays that can be detected by a positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanner [2, 3]. PET uses coincidence detection in lieu of absorptive collimation to determine the positron-electron annihilation, which produces two 511 keV photons in opposite direction. This partially explains the greater spatial resolution and sensitivity of PET. Radioisotopes used in PET imaging typically have short physical half-life and consequently many of them have to be produced with an on-site cyclotron. Radioisotopes used for labeling PET radiopharmaceuticals include 11C, 13N, 15O, 18F, 64Cu, 62Cu, 124I, 76Br, 82Rb, and 68Ga, with 18F being the most clinically utilized. SPECT radiotracers typically have longer physical half-life than most PET tracers; thus a central radiopharmaceutical laboratory can prepare radiotracers for delivery to SPECT facilities within a radius of several hundred miles. There are a range of radioisotopes (such as 99mTc, 201Tl, 67Ga, 123I, and 111In) that can be used for labeling SPECT radiopharmaceuticals, depending on the specific application. 99mTc is the most used radionuclide for nuclear medicine because it is readily available, relatively inexpensive, and gives lower radiation exposure [2–4].

A major advantage of nuclear medicine imaging is the extraordinarily high sensitivity: a typical PET scanner can detect between 10−11 mol/L to 10−12 mol/L concentrations, whereas MRI has a sensitivity of around 10−3 mol/L to 10−5 mol/L [4]. Because many molecules relevant to neuropsychiatric disorders are present at concentrations below 10−8 M, nuclear medicine imaging is currently the only available in vivo method capable of quantifying subtle cerebral pathophysiological changes that might occur before neurostructural abnormalities take place [5].

Radiotracers must fulfill several criteria to be successful for PET or SPECT imaging: including readily labeled with appropriate radionuclide and the labeled radiotracer being stable in vivo and nontoxic; sufficient affinity and high selectivity for the specific receptor combined with low nonspecific binding to brain tissue not containing the receptor of interest; rapid permeation through the blood-brain barrier permitting high access of tracers to receptors, as well as allowing high initial brain uptake and fast clearance of the activity from the brain. A large number of radiotracers have been developed for brain imaging, but most of them were utilized only in vitro or in experimental animals and only few have the potentiality in clinical practice. Selective radiotracers are available for the study of dopaminergic, acetylcholinergic, serotonergic, and norepinephrine systems, as well as β-amyloid plaques with promising results [5, 6].

Dopamine is the most intensely studied monoaminergic neurotransmitter. Dopaminergic neurotransmission plays an important role in regulating several aspects of basic brain function, including motor, behavior, motivation, and working memory, and is involved in the pathogenesis of several psychiatric and neurological disorders. Degeneration of the nigrostriatal dopamine system causes Parkinson's disease (PD) and related Parkinsonism. Postsynaptic receptors may be involved in neurodegenerative disorders; they are functionally changed in Parkinsonism. Dopamine is thought to be involved in drug abuse. Most drugs of abuse, with the exception of benzodiazepines, have a direct effect on increasing the dopamine reward cycle in the brain. Abnormalities within the dopamine system in the brain play a major role in the pathophysiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Dopamine receptors also play an important role in schizophrenia and the effect of neuroleptics is through blockage of dopamine D2 receptors [6]. Neuroimaging techniques permit us to quantify dopaminergic activity in the living human brain, which has become increasingly part of the assessment and diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders. To date, there are numerous PET and SPECT radiotracers available for targeting different steps in the process of dopaminergic neurotransmission. This paper will concentrate on the radiotracers that have been developed for imaging dopaminergic neurons, describe their unique strengths and limitations in the assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders, and suggest future directions in the diagnosis and management of neuropsychiatric disorders.

2. Radiotracers for Imaging Dopaminergic Neurons

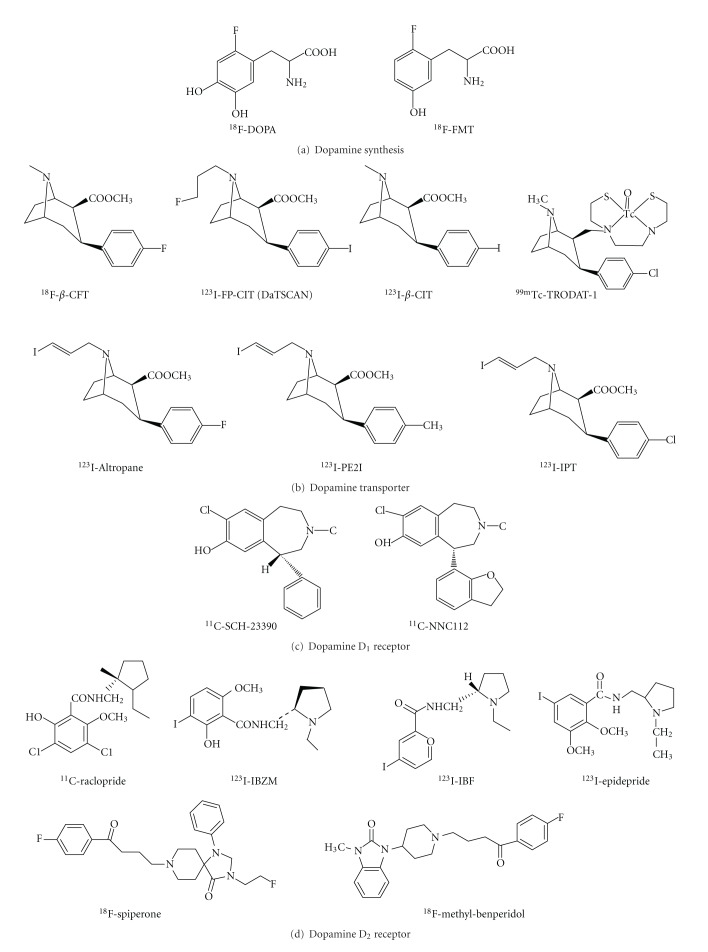

Diagnosis of neurological and psychiatric disorders associated with disturbances of dopaminergic functioning can be challenging, especially in the early stages. The evolution of neuroimaging technique over the past decade has yielded unprecedented information about dopaminergic neurons. PET and SPECT techniques have been successfully employed to visualize the activity of dopamine synthesis, reuptake sites, and receptors (Table 1). The Chemical structure of various radiotracers for the assessment of dopamine system is illustrated on Figure 1. DOPA decarboxylase activity and dopamine turnover can both be measured with 18F-DOPA or 18F-FMT PET [7]. 18F-DOPA PET was the first neuroimaging technique validated for the assessment of presynaptic dopaminergic integrity. The uptake of 18F-DOPA reflects both the density of the axonal terminal plexus and the activity of the striatal aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), the enzyme responsible for the conversion of 18F-DOPA to 18F-dopamine. However, AADC is present in the terminals of all monoaminergic neurons, measurements of 18F-DOPA uptake into extrastriatal areas provides an index of the density of the serotonergic, norepinephrinergic, and dopaminergic terminals [8–10].

Table 1.

Radiotracers available for targeting different steps in the process of dopaminergic neurotransmission and clinical applications.

| Targeting | Tracer | Chemical name | Clinical studies (references) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine synthesis and turn over | 18F-DOPA | L-3,4-dihydroxy-6-[18F]-fluorophenylalanine | PD [11, 20–23], gene therapy for PD [24–26], ADHD [27], schizophrenia [28, 29] |

| 18F-FMT | O-[18F]-fluoromethyl-D-tyrosine | Gene therapy for PD [30, 31] | |

|

| |||

| Dopamine transporter | 11C-CFT | [11C]-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-ltropane | Heroin abuse [32] |

| 11C-altropane | 2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-((E)-3-iodo-prop-2-enyl)tropane | ADHD [33] | |

| 123I-β-CIT (Dopascan) | [123I]-(1R)-2-β-carbomethoxy-3-β-(4-iodophenyl)-tropane | PD [11, 20], PM [34], PD & ET [35], cocaine abuse [36, 37], ADHD [38] | |

| 123I-FP-CIT (DaTSCAN) | [123I] N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane | PM [39–41], PM & ET [42], PD & DLB [43], AD, PD & DLB [44], ADHD [45–47], schizophrenia [48] | |

| 99mTc-TRODAT-1 | [99mTc]technetium [2-[[2-[[[3-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1]oct-2-yl]-methyl](2-mercaptoethyl)amino]-ethyl]amino]ethane-thiolato(3-)-N2,N2′,S2,S2′]oxo-[1R-(exo-exo)] | PD [23, 49–51], MSA [52], PM & VP [53], DRD [54], PSP [55], genetic study of PD [51, 56], genetic study of MJD [57], cocaine abuse [58], opiate abuse [59], nicotine dependence [60, 61], ADHD [62–68] | |

| 123I-altropane | [123I]-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-(1-iodoprop-1-en-3-yl) ortropane | PD [21], ADHD [69] | |

| 123I-IPT | [123I]-N-(3-iodopropen-2-yl)-2-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4-chlorophenyl) tropane | ADHD [70] | |

|

| |||

| Dopamine D1 receptor | 11C-NNC 112 | (+)-5-(7-Benzofuranyl)-8-chloro-7-hydroxy-3-methyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine | Schizophrenia [71] |

| 11C-SCH 23390 | (R)-(+)-8-Chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-3-[11C]methyl-5-phenyl-1H-3-benzazepin-7-ol | Schizophrenia [72, 73] | |

|

| |||

| Dopamine D2 receptor | 11C-Raclopride | 3,5-dichloro-N-{[(2S)-1-ethylpyrrolidin-2-yl]methyl}-2-hydroxy-6-[11C]methoxybenzamide | Drug abuse [74–79] cocaine abuse [80, 81], methamphetamine abuse [82], opiate abuse [83], alcohol dependence [84], ADHD [85, 86], antipsychotics [48, 87–89] |

| 123I-IBZM | (S)-(-)-3-[123I]iodo-2-hydroxy-6-methoxy-N-[(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl]benzamide | PM [40, 41], schizophrenia [90], antipsychotics [89, 91, 92] | |

|

| |||

| vesicular monoamine transporter type-2 | 11C-DTBZ | (±)-α-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine | PD [7, 11, 20] |

| 18F-FP-DTBZ (AV-133) | 9-[18F]fluoropropyl-(+)-dihydrotetrabenazine | PD [93], DLB & AD [94] | |

Abbreviations: Parkinson's disease (PD), Parkinsonism (PM), multiple-system atrophy (MSA), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), essential tremor (ET), vascular Parkinsonism (VP), Machado-Joseph disease (MJD), DOPA-responsive dystonia (DRD), dementia with Lewy bodies disease (DLB), Alzheimer's disease (AD), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of various radiotracers for the assessment of dopamine synthesis, reuptake sites, and receptors.

Dopamine transporter (DAT) is a protein complex located in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals, which serves as the primary means for removing dopamine from the synaptic cleft. The availability of presynaptic DAT can be assessed with various radiotracers, which are typically tropane based [7, 11]. Several PET tracers (11C-CFT, 18F-CFT, 18F-FP-CIT, and 11C-PE2I) and SPECT tracers such as 123I-β-CIT (Dopascan), 123I-FP-CIT (ioflupane, DaTSCAN), 123I-altropane, 123I-IPT, 123I-PE2I, and 99mTc-TRODAT-1 are now available to measure DAT availability [8, 11–17]. 123I-β-CIT was the first widely applied SPECT tracer in imaging DAT, however, the lack of specificity is a disadvantage. This radiotracer binds not only to DAT but also to norepinephrine transporter (NET) and serotonin transporter (SERT). Another disadvantage of 123I-β-CIT is considered not convenient for routine out-patient evaluations since adequate imaging should be performed 20–30 h following the injection [11]. The faster kinetics of 123I-FP-CIT is a clear advantage for clinical use, which allows adequate acquisition as early as 3 h following injection [18]. Conversely, 123I-altropane SPECT images have been less extensively investigated and are more difficult to quantify owing to rapid wash out from the brain [19]. The technetium based 99mTc-TRODAT-1 has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and available in kit form. The easy preparation of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 from lyophilized kits could be an ideal agent for daily clinical application [16]. However, its specific signal is lower than the 123I-based SPECT tracers. To date, only DaTSCAN (123I-FP-CIT) and 99mTc-TRODAT-1 are commercially available in the market and licensed for detecting loss of functional dopaminergic neuron terminals in the striatum.

In the brain, dopamine activates the five known types of dopamine receptors—D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5. Dopamine receptors belong to the G-protein-coupled superfamily. The dopamine D1 and D5 receptor subtypes are known as D1-like receptors and couple to inhibitory G-proteins, whereas the dopamine D2, D3, D4 receptor subtypes are known as D2-like family and couple to stimulatory G-proteins. Only dopamine D1 and D2 receptors have been imaged in humans. For dopamine D1 subtype, the most commonly used radiotracers are 11C-SCH23390 and 11C-NNC112 [7]. As assessment of D1-like receptors has not gained clinical significance; therefore many investigations have focused on the D2-like receptor system in the past. Dopamine D2 receptors are assessed most commonly with the use of benzamide radiotracers. 11C-raclopride, 18F-spiperone, and 18F-methyl-benperidol have been developed for PET imaging; alternatively, 123I-IBZM (123I-iodobenzamide), 123I-epidrpride, and 123I-IBF have been developed for SPECT imaging. 11C-raclopride is currently the gold standard PET tracer for dopamine D2 receptors. In contrast to 11C-raclopride, with a physical half-life of approximately 20 min, 123I-IBZM allows shipment over considerable distances since the radiotracer has a longer physical half-life of 13.2 h [95, 96]. 123I-epidrpride, displaying very high affinity to D2/D3 receptors, has been exploited for quantification and visualization of low density extrastriatal D2/D3 receptors [97].

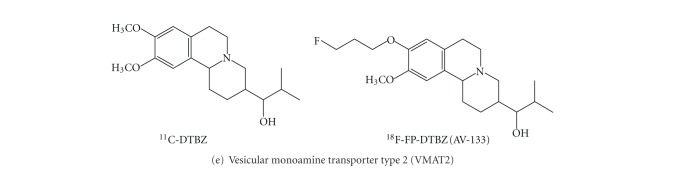

The vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) is expressed by all monoaminergic neurons and serves to pump monoamines from cytosol into synaptic vesicles thereby protecting the neurotransmitters from catabolism by cytosolic enzymes and packaging them for subsequent exocytotic release [98]. In striatum, more than 95% of VMAT2 is associated with dopaminergic terminals and VAMT2 concentration linearly reflects to the concentration of dopamine in the striatum [20, 99]. The most widely used radiotracer is [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ), which binds specifically and reversibly to VMAT2 and is amenable to quantification of striatal, diencephalic, and brain stem neurons and terminals with PET [98]. The 18F-labeled VAMT2 tracer, 18F-FP-DTBZ (AV-133), has been developed with the advantage of having a half-life of nearly 2 h, which allows shipment of tracers over considerable distances to PET centers without an on-site cyclotron [93, 100].

3. Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders

Parkinson's disease, the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by severe loss of dopamine neurons, resulting in a deficiency of dopamine [101, 102]. Clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease relies on the presence of characteristic motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, rigidity and resting tremors, but the rate of misdiagnosis of Parkinson's disease using this method was as high as 24% according to previous studies [103–105]. Good response to dopaminergic drugs, particularly levodopa, is often used to support the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. However, some patients with pathologically confirmed Parkinson's disease have a poor response to levodopa; conversely, some patients with early multiple-system atrophy (MSA) or progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) have beneficial responses to drug treatment [106]. Since the introduction of in vivo molecular imaging techniques, the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease became more reliable by assessing dopaminergic and even nondopaminergic systems [107].

Imaging of striatal denervation in Parkinson's disease was first reported with 18F-DOPA PET and has been extended in imaging studies of DAT and VMAT2 [11, 13, 14, 21–23, 34, 39, 49, 94, 98, 108]. All these markers demonstrate reduced uptake in the striatum, the location of the presynaptic nigral dopamine terminal projections. More specifically, these imaging studies in Parkinson's disease patients have shown the nigral neuron loss is asymmetric, where the putamenal reductions are more profound than those in caudate [10]. Studies with 18F-DOPA and DAT tracers indicated a reduction in radiotracer uptake of approximately 50–70% in the putamen in Parkinson's disease subjects [21, 34, 39, 49]. In general, all these DAT markers show similar findings in Parkinson's disease to those seen with 18F-DOPA PET and are able to differentiate early Parkinson's disease from normal subjects with a sensitivity of around 90% [6, 50]. A multicenter phase III trial conducted at Institute of Nuclear Energy Research (INER) in Taiwan indicated that patients with Parkinson's disease were easily distinguished from healthy volunteers with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT, which had a sensitivity of 97.2% and a specificity of 92.6% (unpublished data).

18F-DOPA PET is considered as a standard procedure for evaluating dopaminergic metabolism. However, use of 18F-DOPA PET may sometimes overestimate the nigral cell reserve in Parkinson's disease, since it may show a better than actual uptake due to compensatory increased activity of dopa decarboxylase that occurs with dopamine cell terminal loss [11]. On the contrary, the striatal uptake of DAT radiotracers in early Parkinson's disease may overestimate the reduction in terminal density due to the relative downregulation of DAT in the remaining neurons as a response to nigral neuron loss, a compensatory mechanism that acts to maintain synaptic dopamine levels [23]. Additionally, DAT activity falls with age in healthy subjects, but striatal 18F-DOPA uptake does not appear to be age dependent [8, 9, 22].

The signs and symptoms present in early Parkinson's disease can resemble those of many other movement disorders, particularly other forms of parkinsonism such as progressive supranuclear palsy, progressive supranuclear palsy, drug-induced Parkinsonism (DIP), vascular Parkinsonism (VP), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and essential tremor (ET) [10, 40]. It is important to discriminate between idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD) and other neurodegenerative Parkinsonian syndromes because there are marked differences in the prognoses and therapies.

Neuroimaging studies indicate that the pattern of dopaminergic neurons loss in Parkinsonian syndromes is less region-specific than in idiopathic Parkinson's disease, the putamen and caudate are more equally effected. Moreover, left and right striatal radiotracer uptake in these disorders is also more symmetric than in idiopathic Parkinson's disease [10]. Lu et al. found DAT imaging with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 probably could provide important information to differentiate progressive supranuclear palsy from Parkinson's disease. The striatal binding was more symmetrically reduced in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy, in contrast to the greater asymmetric reduction in the Parkinson's disease groups [52]. Essential tremor is a condition most commonly misdiagnosed with Parkinson's disease; up to 25% of cases are initially diagnosed as having Parkinson's disease. DAT imaging using 123I-β-CIT and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT has been successfully proven in differentiating essential tremor from Parkinson's disease; subjects with essential tremor have normal levels of striatal uptake. Such studies have found the sensitivity and specificity for clinical diagnosis of distinguishing Parkinson's disease from essential tremor to be 95% and 93%, respectively [35, 42]. Vascular Parkinsonism is a disorder caused by cerebrovascular disease and accounts for 4.4–12% of all cases of Parkinsonism [109]. Dopaminergic imaging studies may help with the diagnosis of vascular Parkinsonism, although studies have provided conflicting results. Two studies (using 123I-β-CIT or 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT) found near normal DAT binding in patients with vascular Parkinsonism, differentiating them from patients with Parkinson's disease, whereas other studies have found reduced DAT binding in some patients with vascular Parkinsonism [19, 34, 53]. Dementia with Lewy bodies, characterized by severe nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuron degeneration, is the second most common form of degenerative dementia (after Alzheimer's disease, AD). Accurate diagnosis in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies is particularly important in the early stage of the disease for the treatment and management of the patient. 18F-DOPA, DAT, and VMAT2 markers can differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies, who display lower striatal binding in the putamen, caudate, and midbrain, from those with Alzheimer's disease, who have normal striatal binding similar to those observed in healthy controls. Mean sensitivity of 123I-FP-CIT scans for a clinical diagnosis of probable dementia with Lewy bodies was 77.7%, while the mean specificity for excluding non-Lewy body dementia was 90.4%, giving overall diagnostic accuracy of 85.7% [19, 43, 44, 94]. In addition, a DAT study with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 scan in DOPA-responsive dystonia (DRD) patients, a hereditary progressive disorder with sustained response to low-dosage levodopa but entirely different prognosis from Parkinson's disease, showed significant higher DAT uptake in patients with DOPA -responsive dystonia than those in patients with young onset Parkinson disease (P < 0.001), suggesting a normal nigrostriatal presynaptic dopaminergic terminal in DOPA -responsive dystonia [54].

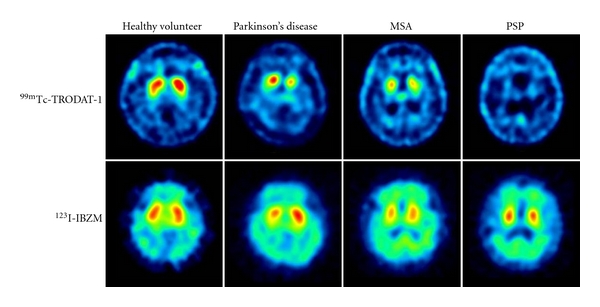

Higher diagnostic accuracy in the differential diagnosis of Parkinsonism may be achieved by combining pre- and postsynaptic quantitative information about the dopaminergic system. Previous imaging studies with the most commonly used dopamine D2 receptor tracers, 11C-raclopride and 123I-IBZM, have shown that the uptake of DAT are downregulated in patients with early idiopathic Parkinson's disease, but D2 receptors are comparable to normal subjects in medicated Parkinson's disease patients and may even be mildly increased in unmedicated patients. With the progression of Parkinson's disease, striatal D2 receptor activity returns to normal or may fall below normal levels [98]. In contrast to Parkinson's disease, patients with atypical Parkinsonism like progressive supranuclear palsy or progressive supranuclear palsy typically show reductions in both DAT and D2 binding [7, 40, 41]. Figure 2 illustrates the DAT scans with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 and the D2 receptor scans with 123I-IBZM of healthy volunteer and patients with Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy. However, the small differences in D2 binding failed to discriminate between idiopathic Parkinson's disease, nonidiopathic Parkinson's disease, and healthy control groups, according to a report of a multicenter phase III trial conducted by INER (unpublished data). Nevertheless, the dopamine D2 receptor imaging is successfully demonstrated in differentiation of the subtypes of progressive supranuclear palsy: Richardson's syndrome (RS) and progressive supranuclear palsy-parkinsonism (PSP-P). Assessment of pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic activities in Richardson's syndrome, PSP-P, or idiopathic Parkinson's disease with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 and 123I-IBZM images showed that the activities of D2 receptor were reduced in Richardson's syndrome but not in PSP-P (P < 0.01), which was consistent with the clinical manifestation of PSP-P group with better prognosis and levodopa responsiveness than that of RS patients [55].

Figure 2.

Dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 and dopamine D2 receptor imaging with 123I-IBZM of healthy volunteer and patients with Parkinson's disease (PD), multiple-system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). The striatal DAT uptakes were significantly decreased in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP, whereas the dopamine D2 receptor uptakes were mildly decreased in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP.

Imaging the distribution and density of single molecules in the living brain will give us straightforward information of the genetic linkages among different aspects of Parkinsonism. Genetic studies have identified at least 9 genes with mutation that cause 10% to 15% of Parkinson's disease cases [103]. SNCA, Parkin, PINK1, DJ-1, LRRK2, and ATP13A2 have been identified to be the causative genes for familial and early onset Parkinson's disease (EOPD) [51]. A 99mTc-TRODAT-1 scan revealed that patients with the PINK1 mutation displayed a rather even, symmetrical reduction of dopamine uptake, whereas patients with late-onset Parkinson's disease (LOPD) displayed a dominant decline in dopamine uptake in the putamen [56]. The contribution of genetic variants in ATP13A2 to Parkinson's disease of Taiwanese patients was investigated with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT, showing that the striatal uptake of patients carrying the variants of G1014S and A746T were similar to that of idiopathic Parkinson's disease [51]. In addition, 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT was exploited to examine the DAT activity in Machado-Joseph disease (MJD) patients and gene carriers, showing that the DAT concentration was significantly reduced in patients with Machado-Joseph disease and in asymptomatic gene carriers compared to those of healthy volunteers (P < 0.001) [57].

Molecular imaging is also a major tool for the evaluation of new experimental therapeutic strategies in Parkinson's disease. Cell transplantation to replace lost neurons is a recent approach to the treatment of progressive neurodegenerative diseases. Transplantation of human embryonic dopamine neurons into the brains of patients with Parkinson's disease has proved beneficial in open clinical trials [7, 24]. Several teams of investigators have reported the results from double-blind placebo-controlled trials of human embryonic dopaminergic tissue transplantation for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Evaluations with 18F-DOPA scans have shown that significant declines in the motor scores over time after transplantation (P < 0.001), based on the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), were associated with increases in putamen 18F-DOPA uptake at 4 years posttransplantation followups (P < 0.001). Furthermore, posttransplantation changes in putamen PET signals and clinical outcomes were significantly intercorrelated (P < 0.02) [24, 25]. Gene therapy may be potentially useful for ameliorating the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Several gene therapy studies in humans investigated transductions (with various viral vectors) of glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurturin (NTN), AADC, or glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). Brain imaging with 18F-DODA or 18F-FMT PET has been exploited to evaluate clinical outcomes adjunct to the UPDRS scores [26, 30, 31, 110–112].

4. Drug Abuse and Addicted Brain

Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that has been classically associated with the reinforcing effects of drug abuse. This notion reflects the fact that most of the drugs of abuse increase extracellular dopamine concentration in limbic regions including nucleus accumbens (NAc). The involvement of dopamine in drug reinforcement is well recognized but its role in drug addiction is much less clear. Imaging studies have provided evidences of how the human brain changes as an individual becomes addicted [74–77].

Cocaine is considered one of the most reinforcing drug of abuse; therefore, this drug has been extensively investigated the associated reinforcing effects in humans. Cocaine is believed to work by blocking the DAT and thereby increasing the availability of free dopamine within the brain. The relationship between DAT blockage and the reinforcement effects of cocaine abuser has been assessed with 11C-cocaine PET, showing that intravenous cocaine at doses commonly abused by human (0.3–0.6 mg/kg) blocked between 60 to 77% of DAT sites in these subjects. Moreover, the magnitude of the self-reported “high” was positively correlated with the degree of DAT occupancy, and at least 47% of the transporters had to be blocked for subjects to perceive cocaine's effects [80]. When compared to normal controls, cocaine abusers showed significant decreases in dopamine D2 receptor availability that persisted 3-4 months after detoxification. Decreases in dopamine D2 receptor availability were associated with decreased metabolism in several regions of the frontal lobes, most markedly in orbito-frontal cortex and cingulate gyri [81]. PET studies with 11C-raclopride have consistently shown that subjects with a wide variety of drug addictions (cocaine, heroin, alcohol, and methamphetamine) have significant reductions in dopamine D2 receptor availability in the striatum that persist months after protracted detoxification [76, 78, 82–84, 113].

Since dopamine D2 receptors are involved in the response to reinforcing properties of natural as well as drug stimuli, it has been postulated that reduced D2 receptor levels in drug-addicted subjects would make them less sensitive to natural reinforcers. Volkow et al. compared the function of the dopamine system of 20 cocaine-dependent subjects with 23 controls using 11C-raclopride PET by measuring the relative changes in extracellular dopamine induced by intravenous methylphenidate. Cocaine-dependent subjects showed reduced dopamine release in the striatum and also had a reduced “high” relative to controls, indicating that methylphenidate-induced striatal dopamine increased in cocaine abusers were significantly blunted when compared with those of controls [74, 113].

Despite the similarities between cocaine and methylphenidate in their affinity to the DAT, cocaine is much more abused than methylphenidate. Using 11C labeled cocaine and methylphenidate for PET imaging, it has been demonstrated that the regional distribution of 11C-methylphenidate was identical to that of 11C-cocaine and they competed with each other for the same binding site. However, these two drugs differed markedly in their pharmacokinetics. Both drugs entered the brain rapidly after intravenous administration (in less than 10 min) while the rate of clearance of 11C-methylphenidate from striatum (90 min) was significantly slower than that of 11C-cocaine (20 min). Therefore, it is postulated that the initial uptake of these stimulant drugs into the brain, not their steady-state presence, is necessary for drug-induced reinforcement [76, 114].

In addition to differences in bioavailability, the route of administration significantly affects the effects of stimulant drugs presumably via its effects on pharmacokinetics. This is particularly relevant to methylphenidate because it is abused when taken intravenously but rarely so when taken orally. Volkow et al. measured the dopamine changes induced by oral and intravenous administration of methylphenidate that produce equivalent DAT occupancy (about 70%). Even though the dopamine increases were comparable for oral and intravenous (approximately 20% changes in specific binding of 11C-raclopride in striatum), oral methylphenidate did not induce significant increases in self-reports of “high.” Intravenous administration of methylphenidate leads to fast dopamine changes, whereas oral administration increases dopamine slowly. The failure to observe the “high” with oral methylphenidate is likely to reflect the slower pharmacokinetics [76, 77, 85].

A view of DAT regulation in cocaine addicts may improve our understanding of clinical aspects of cocaine dependence, including drug-induced carving, dysphoria, and relapse. The DAT levels in the brain of cocaine-dependence were measured by 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT. It has shown that there were significantly higher DAT levels in cocaine-dependent subjects compared to controls for the anterior putamen, posterior putamen, and caudate. DAT levels in these regions were 10%, 17%, and 8% higher in the cocaine dependent subjects compared to controls. This study also showed that 99mTc-TRODAT-1 uptake was negatively correlated with the duration of time since last use of cocaine [58]. Malison et al. examined the striatal DAT levels in 28 cocaine-abusing subjects with 123I-β-CIT SPECT and found that striatal DAT levels were significantly increased (approximately 20%) in acutely abstinent cocaine-abusing subjects (96 h or less) [36]. Another study using 123I-β-CIT SPECT also showed approximately a 14% increase in DAT availability in acutely abstinent (3.7 days on average) cocaine subjects compared to controls [37].

Human imaging studies suggest that preexisting differences in dopamine circuits may be one mechanism underlying the variability in responsiveness to drug abuse. In particular, baseline measures of striatal dopamine D2 receptors in nonaddicted subjects have been shown to predict subjective responses to the reinforcing effects of intravenous methylphenidate treatment. Individuals describing the experience as pleasant had substantially lower levels of dopamine D2 receptors compared with those describing methylphenidate as unpleasant [74, 79].

Methadone maintenance treatment has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing or eliminating opioid drug use. Despite its therapeutic effectiveness, relatively little is known about neuronal adaptations in the brains of methadone users. A PET study with 11C-CFT has documented reduced DAT availability in patients with prolonged abstinence and with methadone maintenance treatment. Furthermore, the subjects with methadone maintenance treatment showed significant decreases of DAT uptake function in the bilateral putamen in comparison to the prolonged abstinence subjects [32]. Another study examined the differences between opioid-dependent users treated with a very low dose of methadone or undergoing methadone-free abstinence. The striatal DAT availability was significantly reduced in low-dose methadone users (0.78 ± 0.27) and methadone-free abstinence (0.94 ± 0.28) compared to controls (1.16 ± 0.26), which has demonstrated that methadone treatment or abstinence can benefit the recovery of impaired dopamine neurons. Moreover, lower midbrain SERT availability also was noted in methadone maintenance treatment and methadone-free abstinence groups, which implicated deregulation of serotoninergic neurons in opioid abuse [59].

The behavioral and neurobiological effects of tobacco smoking, in which nicotine may play an import role, are similar to those of addictive drugs. The pre- and postsynaptic activity of dopamine neuron was examined in male smokers with 99mTc-TRODAT-1/123I-IBZM SPECT. A decrease in DAT availability was found in the striatum of male smokers (P < 0.05), suggesting cigarette smoking may alter central dopamine functions, particularly at the presynaptic sites. Moreover, the total FTND (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence) scores correlated negatively with striatal DAT availability in male smokers, but not with striatal D2 bindings [60].

5. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common disorder of childhood characterized by inattention, excessive motor activity, impulsiveness, and distractibility. It is associated with serious disability in children, adolescents and adults. There is converging evidence that abnormalities within the dopamine system in the brain play a major role in the pathophysiology of ADHD [33, 62, 63]. Despite extensive investigation of the neuropathophysiology of ADHD by a wide array of methodologies, the mechanism underlying this disorder is still unknown.

Neuroimaging holds promise for unveiling the neurobiological causes of ADHD and provides invaluable information for management of the disease. Ernst et al. investigated the integrity of presynaptic dopaminergic function in children with ADHD through the use of 18F-DOPA PET and found a 48% increase in DOPA decarboxylase activation in the right midbrain in ADHD children compared with normal controls [27].

Methylphenidate is considered as a first-line medication for ADHD in children and adults [86, 115]. This medicine is very effective for the treatment of ADHD; it is estimated that 60–70% of ADHD subjects have favorable responses. Volkow et al. utilized 11C-cocaine and 11C-raclopride PET to assess the DAT and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy for a given dose of methylphenidate. It has been proven that this drug significantly blocked DAT (60 ± 11%) and increased synaptic dopamine levels (16 ± 8%) reduction in 11C-raclopride binding in the striatum [86].

It is widely accepted that the therapeutic effects of methylphenidate are through the blocking of DAT; therefore, it seems appropriate to investigate the DAT availability in patients with ADHD. The first DAT imaging study was conducted in 6 adults with ADHD by using 123I-altropane SPECT, showing that the DAT levels in unmedicated patients were approximately 70% higher than those in controls [69]. However, following studies with a variety of DAT markers have shown a much smaller increase even not reaching statistical significance than that found in the first study with 123I-altropane [38, 45, 64, 65, 70]. Dresel et al. investigated DAT binding in 17 treatment naïve adults with ADHD compared with 10 age- and gender-matched control subjects by using 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT. Patients with ADHD exhibited a significantly increased specific DAT binding in the striatum (average 17%) compared with normal subjects (P < 0.01) [64]. Furthermore, Krause et al. examined DAT binding in an expanded sample of 31 adults with ADHD and 15 control subjects; the earlier findings of greater DAT binding in adults with ADHD was replicated [62]. DAT density has been compared in 9 treatment naïve children with ADHD and 6 normal children using 123I-IPT SPECT, showing that mean DAT binding in the basal ganglia was significantly increased with 40% on the left and 51% on the right side compared with the controls [70]. By using 11C-altropane PET, a highly selective radiotracer and technically superior imaging modality, Spencer et al. found that the overall DAT binding was increased 28% in adults with ADHD compared with controls [33]. However, the 123I-β-CIT SPECT study showed no significant difference in striatal density between adult patients with ADHD and normal controls [38]. Furthermore, Hesse et al. found the striatal DAT binding ratio (specific to nondisplaceable binding) was significantly reduced in treatment naïve adults with ADHD by using 123I-FP-CIT SPECT (ADHD: 5.18 ± 0.98; control: 6.36 ± 1.34) [46]. The cause of divergent findings might be the clinical heterogeneity of the ADHD phenotype rather than differences in imaging technology, applied tracer type, or outcome measurement method.

It has been shown that methylphenidate lowers DAT availability very effectively in normal subjects and in patients with ADHD. After treatment with methylphenidate (5 mg t.i.d), the specific DAT binding decreased (average 29%) significantly in all patients (P < 0.01), investigated by 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT [64]. Vles et al. examined DAT binding in 6 treatment naïve boys with ADHD (aged 6–10 years), using 123I-FP-CIT SPECT. Three months after treatment with methylphenidate, a 28–75% decrease of DAT binding in the striatum was found [47]. Generally nonresponse to methylphenidate is known to occur in approximately 30% of patients with ADHD, which may be caused by lower baseline DAT availability in these patients. Krause et al. assessed the relationship between DAT availability and treatment outcome using 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT. It has shown that ADHD patients with poor response to methylphenidate had a low primary DAT availability, whereas most of patients with high DAT availability exhibited good clinical response to methylphenidate [66, 67].

Previous studies have confirmed the reduction of DAT availability by nicotine [60, 61]. Patients with ADHD and with a history of nicotine abuse displayed lower DAT availability than nonsmokers with ADHD. DAT seems to be elevated in nonsmoking ADHD patients suffering from the purely inattentive subtype of ADHD as well as in those with the combined or purely hyperactive/impulsive subtype [63, 68].

6. Schizophrenia and the Effects of Antipsychotics

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness characterized by disturbances of thoughts, perceptions, volition, and cognition. Manifestations of the illness are commonly divided into positive (delusions, hallucinations, thought disorganization, paranoia), negative (lack of drive and motivation, alogia, social withdrawal), and cognitive symptoms (poor performance on cognitive tasks involving attention and working memory). Positive symptoms are considered to be a result of the increased subcortical release of dopamine causing greater stimulation of D2 receptors. The negative and cognitive symptoms are thought to arise from reduced D1 receptor stimulation [28, 90, 116].

With the advance of brain imaging techniques, direct evidence suggestive of dysregulation of dopaminergic transmission in schizophrenia has emerged. Several lines of study have documented an increase in the striatal accumulation of 18F-DOPA or 11C-DOPA in patients with schizophrenia, which is consistent with increased activity of DOPA decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in dopamine synthesis [28, 90]. More recently, Howes et al. assessed striatal dopaminergic function in patients with prodromal schizophrenia using 18F-DOPA PET and found elevated striatal 18F-DOPA uptake, which gradually reached the level in those with schizophrenia. In addition, increased striatal 18F-DOPA uptake was correlated with the severity of prodromal psychopathologic and neuropsychological impairment [29].

Since the primary target of many antipsychotic drugs is antagonism at striatal D2 receptors, Abi-Dargham et al. compared striatal D2 receptor availability before and during pharmacologically induced acute dopamine depletion with 123I-IBZM SPECT in 18 untreated patients and 18 controls. At baselines, no difference has been found between these 2 groups. However, after depletion of endogenous dopamine, D2 receptor availability was significantly higher in patients with schizophrenia compared with controls (P < 0.01). In addition, the study suggests elevated synaptic dopamine is predictive of good treatment response of positive symptoms to antipsychotic drugs [90].

PET studies with 11C-SCH2390 or 11C-NNC112 in drug naïve schizophrenia patients have reported divergent findings in D1 receptor binding and cognitive functioning. Some studies have shown a decrease in prefrontal D1 receptor binding [72], whereas others have shown an increase in D1 receptor binding [71] or reported no differences between patients and controls [73]. A few have shown a relationship between D1 dysfunction and working memory performance in treatment naïve patients. The variability in the results was possibly influenced by parameters of the particular patient populations including duration of illness, symptoms and medications.

Nuclear medicine imaging technique has been widely used for the drug development in recent years. There are several approaches such as microdosing, measurement of in vivo receptor occupancy, and biomarkers [117]. Most imaging studies in the past have concentrated on antipsychotics. Several lines of research indicate the efficacy of antipsychotics to be related to their capacity to antagonize dopamine. Brain Imaging with PET or SPECT allows determination of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy rate in the human brain during treatment with antipsychotics, which are associated with extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) of antipsychotic drugs [118]. Farde et al. found that the classical antipsychotics occupied 60–85% of striatal dopamine D2 receptor was necessary for treating positive symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by 11C-raclopride PET imaging. However, D2 receptor occupancies above 80% were associated with a significantly higher risk of extrapyramidal symptoms [87, 118, 119].

Several new antipsychotics have been introduced to market with lower affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, for which the term “atypical antipsychotics” had been coined. Atypical antipsychotics display with a low or nonexistent propensity of extrapyramidal symptoms as compared to classical neuroleptics [88].

Therapeutic concentrations reported from clinical studies have been confirmed by D2 receptor imaging for classical antipsychotics and a number of atypical antipsychotics (i.e., amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, and zotepine). From available studies, the atypical antipsychotics clozapine and quetiapine appear to have the lowest striatal D2 receptor occupancy rates and the typical antipsychotic haloperidol has the highest. Risperidone, sertindole, and zotepine hold an intermediate position. The incidence of EPS ranged from none with clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, to 80% of patients treated with haloperidol [89, 91, 92, 120]. The effect of DAT on a neuroleptic was examined by 123I-FP-CIT SPECT. Mateos and coworkers found in schizophrenic patients 4 weeks of treatment with risperidone did not influence striatal DAT binding ratios significantly [48].

7. Conclusions

With the appropriate radiotracers, neuroimaging enables the visualization of the presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in the dopaminergic system. Imaging these markers provides key insights into the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease and related neurodegenerative diseases and it becomes an important endpoint in clinical trials of potential disease-modifying therapy for Parkinson's disease such as gene therapy or cell replacement therapy. The availability of easy-to-apply diagnostic procedures such as metabolic and DAT imaging is encouraging. Nonetheless, it should also be emphasized that these results are no replacement for thorough clinical investigation. Future studies are needed in the development of new radiotracers to target nondopaminergic brain pathways and the glial reaction to disease.

Neuroimaging studies have provided evidences of how the human brain changes as an individual becomes addicted. Although available studies have mostly focused on dopamine, the interaction of dopamine with other neurotransmitters such as GABA, glutamate, and serotonin plays an important role in modulating the magnitude of the dopamine responses to drugs.

At this time, knowledge from DAT imaging studies in patients with ADHD is limited by the use of various radiotracers and small sample size. In the future, measurements of DAT with PET or SPECT should be performed in greater collectives, allowing the assignment to different subtypes of ADHD. Of further interest will be whether the DAT availability has a prognostic value for the treatment response of methylphenidate. Furthermore, since methylphenidate exerts its therapeutic efficacy is through blocking DAT and NET, the role of norepinephrinergic system in the pathophysiology of ADHD will become increasing important as the recently available of NET radiotracers.

The clinically most important contribution from neuroimaging on D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia is probably the identification of the optimal therapeutic window for antipsychotic drugs. Based on this concept, the striatal D2 receptors binding profiles of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents has been determined.

In the future, the role of neuroimaging may become more significant in guiding therapy. Enhancements in image resolution and specific molecular tags will permit accurate diagnoses of a wide range of diseases, based on both structural and molecular changes in the brain. For widespread application, advances in molecular imaging should include the characterization of new radiotracers, application of modeling techniques, standardization and automation of image-processing techniques, and appropriate clinical settings in large multicenter trials. The growing field of neuroimaging is helping nuclear medicine physicians identify pathways into personalized patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the research teams of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital for carrying out the clinical studies for the neuroimaging agents developed at Institute of Nuclear Energy Research. The development of neuroimaging agents was partially supported by the Grant from National Science Council (NSC99-3111-Y-042A-013).

References

- 1.Wong DF, Gründer G, Brasic JR. Brain imaging research: does the science serve clinical practice? International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19(5):541–558. doi: 10.1080/09540260701564849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metter FA, Guiberteau MJ. Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Imaging. 5th edition. chapter 1. Saunders, Elsevier; 2006. Radioactivity, radionuclides, and radiopharmaceuticals; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metter FA, Guiberteau MJ. Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Imaging. 5th edition. chapter 13. Saunders, Elsevier; 2006. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging; pp. 359–423. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Molecular imaging. Radiology. 2001;219(2):316–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fumita M, Innis RB. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. 1st edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiss WD, Herholz K. Brain receptor imaging. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47(2):302–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sioka C, Fotopoulos A, Kyritsis AP. Recent advances in PET imaging for evaluation of Parkinson’s disease. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2010;37(8):1594–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavese N, Brooks DJ. Imaging neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1792(7):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavese N, Kiferle L, Piccini P. Neuroprotection and imaging studies in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2010;15(supplement 4):S33–S37. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seibyl JP. Imaging studies in movement disorders. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 2003;33(2):105–113. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2003.127303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks DJ, Frey KA, Marek KL, et al. Assessment of neuroimaging techniques as biomarkers of the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Neurology. 2003;184(supplement 1):S68–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rinne JO, Laihinen A, Någren K, Ruottinen H, Ruotsalainen U, Rinne UK. PET examination of the monoamine transporter with [11C]β-CIT and [11C]β-CFT in early Parkinson’s disease. Synapse. 1995;21(2):97–103. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinne JO, Ruottinen H, Bergman J, Haaparanta M, Sonninen P, Solin O. Usefulness of a dopamine transporter PET ligand [18F]β-CFT in assessing disability in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;67(6):737–741. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinne JO, Nurmi E, Ruottinen HM, Bergman J, Eskola O, Solin O. [18F]FDOPA and [18F]CFT are both sensitive PET markers to detect presynaptic dopaminergic hypofunction in early Parkinson’s disease. Synapse. 2001;40(3):193–200. doi: 10.1002/syn.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meegalla SK, Plössl K, Kung MP, et al. Synthesis and characterization of technetium-99m-labeled tropanes as dopamine transporter-imaging agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1997;40(1):9–17. doi: 10.1021/jm960532j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kung MP, Stevenson DA, Plössl K, et al. [99mTc]TRODAT-1: a novel technetium-99m complex as a dopamine transporter imaging agent. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1997;24(4):372–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00881808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro MJ, Vidailhet M, Loc’h C, et al. Dopaminergic function and dopamine transporter binding assessed with positron emission tomography in Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology. 2002;59(4):580–586. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booij J, Tissingh G, Winogrodzka A, et al. Practical benefit of [123I]FP-CIT SPET in the demonstration of the dopaminergic deficit in Parkinson’s disease. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1997;24(1):68–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01728311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings JL, Henchcliffe C, Schaier S, Simuni T, Waxman A, Kemp P. The role of dopaminergic imaging in patients with symptoms of dopaminergic system neurodegeneration. Brain. 2011;134(11):3146–3166. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravina B, Eidelberg D, Ahlskog JE, et al. The role of radiotracer imaging in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(2):208–215. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149403.14458.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez HH, Friedman JH, Fischman AJ, Noto RB, Lannon MC. Is altropane SPECT more sensitive to fluoroDOPA PET for detecting early Parkinson’s disease? Medical Science Monitor. 2001;7(6):1339–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nurmi E, Ruottinen HM, Bergman J, et al. Rate of progression in Parkinson’s disease: a 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa PET study. Movement Disorders. 2001;16(4):608–615. doi: 10.1002/mds.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang WS, Chiang YH, Lin JC, Chou YH, Cheng CY, Liu RS. Crossover study of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT and 18F-FDOPA PET in Parkinson’s disease patients. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44(7):999–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, et al. Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(10):710–719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y, Tang C, Chaly T, et al. Dopamine cell implantation in Parkinson’s disease: long-term clinical and 18F-FDOPA PET outcomes. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(1):7–15. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marks WJ, Jr., Ostrem JL, Verhagen L, et al. Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: an open-label, phase I trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7(5):400–408. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernst M, Zametkin AJ, Matochik JA, Pascualvaca D, Jons PH, Cohen RM. High midbrain [18F]DOPA accumulation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1209–1215. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel NH, Vyas NS, Puri BK, Nijran KS, Al-Nahhas A. Positron emission tomography in schizophrenia: a new perspective. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(4):511–520. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):13–20. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eberling JL, Jagust WJ, Christine CW, et al. Results from a phase I safety trial of hAADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70(21):1980–1983. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312381.29287.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muramatsu SI, Fujimoto KI, Kato S, et al. A phase I study of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Molecular Therapy. 2010;18(9):1731–1735. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi J, Zhao LY, Copersino ML, et al. PET imaging of dopamine transporter and drug craving during methadone maintenance treatment and after prolonged abstinence in heroin users. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;579(1–3):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Madras BK, et al. In vivo neuroreceptor imaging in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a focus on the dopamine transporter. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinn N. A multicenter assessment of dopamine transporter imaging with DOPASCAN/SPECT in parkinsonism. Neurology. 2001;57(4):746–747. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.746-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asenbaum S, Pirker W, Angelberger P, Bencsits G, Pruckmayer M, Brucke T. [123I] β-CIT and SPECT in essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neural Transmission. 1998;105(10–12):1213–1228. doi: 10.1007/s007020050124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malison RT, Best SE, van Dyck CH, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine transporters during acute cocaine abstinence as measured by [123I]β-CIT SPECT. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(6):832–834. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobsen LK, Staley JK, Malison RT, et al. Elevated central serotonin transporter binding availability in acutely abstinent cocaine-dependent patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(7):1134–1140. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Dyck CH, Quinlan DM, Cretella LM, et al. Unaltered dopamine transporter availability in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):309–312. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booij J, Speelman JD, Horstink MWIM, Wolters EC. The clinical benefit of imaging striatal dopamine transporters with [123I]FP-CIT SPET in differentiating patients with presynaptic parkinsonism from those with other forms of parkinsonism. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;28(3):266–272. doi: 10.1007/s002590000460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch W, Hamann C, Radau PE, Tatsch K. Does combined imaging of the pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic system increase the diagnostic accuracy in the differential diagnosis of parkinsonism? European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2007;34(8):1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plotkin M, Amthauer H, Klaffke S, et al. Combined 123I-FP-CIT and 123I-IBZM SPECT for the diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes: study on 72 patients. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2005;112(5):677–692. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benamer TS, Patterson J, Grosset DG, et al. Accurate differentiation of parkinsonism and essential tremor using visual assessment of [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT imaging: the [123I]-FP-CIT study group. Movement Disorders. 2000;15(3):503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colloby S, O’Brien J. Functional imaging in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2004;17(3):158–163. doi: 10.1177/0891988704267468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien JT, Colloby S, Fenwick J, et al. Dopamine transporter loss visualized with FP-CIT SPECT in the differential diagnosis of dementia with lewy bodies. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61(6):919–925. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larisch R, Sitte W, Antke C, et al. Striatal dopamine transporter density in drug naive patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2006;27(3):267–270. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hesse S, Ballaschke O, Barthel H, Sabri O. Dopamine transporter imaging in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2009;171(2):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vles JSH, Feron FJM, Hendriksen JGM, Jolles J, van Kroonenburgh MJPG, Weber WEJ. Methylphenidate down-regulates the dopamine receptor and transporter system in children with Attention Deficit Hyperkinetic Disorder (ADHD) Neuropediatrics. 2003;34(2):77–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mateos JJ, Lomeña F, Parellada E, et al. Lower striatal dopamine transporter binding in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients is not related to antipsychotic treatment but it suggests an illness trait. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):805–811. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang WS, Lin SZ, Lin JC, Wey SP, Ting G, Liu RS. Evaluation of early-stage Parkinson’s disease with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 imaging. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42(9):1303–1308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weng YH, Yen TC, Chen MC, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT imaging in differentiating patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease from healthy subjects. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(3):393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CM, Lin CH, Juan HF, et al. ATP13A2 variability in Taiwanese Parkinson’s disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics B. 2011;156(6):720–729. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu CS, Weng YH, Chen MC, et al. 99mTc-TRODAT-1 imaging of multiple system atrophy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tzen KY, Lu CS, Yen TC, Wey SP, Ting G. Differential diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and vascular parkinsonism by 99mTc-TRODAT-1. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42(3):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang CC, Yen TC, Weng YH, Lu CS. Normal dopamine transporter binding in dopa responsive dystonia. Journal of Neurology. 2002;249(8):1016–1020. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0776-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin WY, Lin KJ, Weng YH, et al. Preliminary studies of differential impairments of the dopaminergic system in subtypes of progressive supranuclear palsy. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2010;31(11):974–980. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32833e5f90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weng YH, Chou YHW, Wu WS, et al. PINK1 mutation in Taiwanese early-onset parkinsonism: clinical, genetic, and dopamine transporter studies. Journal of Neurology. 2007;254(10):1347–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yen TC, Tzen KY, Chen MC, et al. Dopamine transporter concentration is reduced in asymptomatic Machado-Joseph disease gene carriers. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43(2):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crits-Christoph P, Newberg A, Wintering N, et al. Dopamine transporter levels in cocaine dependent subjects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98(1-2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeh TL, Chen KC, Lin SH, et al. Availability of dopamine and serotonin transporters in opioid-dependent users—a two-isotope SPECT study. Psychopharmacology. 2012;220(1):55–64. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang YK, Yao WJ, Yeh TL, et al. Decreased dopamine transporter availability in male smokers—a dual isotope SPECT study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Newberg A, Lerman C, Wintering N, Ploessl K, Mozley PD. Dopamine transporter binding in smokers and nonsmokers. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2007;32(6):452–455. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000262980.98342.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, la Fougere C, Ackenheil M. The dopamine transporter and neuroimaging in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27(7):605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krause J. SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2008;8(4):611–625. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dresel S, Krause J, Krause KH, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the dopamine transporter before and after methylphenidate treatment. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2000;27(10):1518–1524. doi: 10.1007/s002590000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K. Increased striatal dopamine transporter in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate as measured by single photon emission computed tomography. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;285(2):107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krause J, la Fougere C, Krause KH, Ackenheil M, Dresel SH. Influence of striatal dopamine transporter availability on the response to methylphenidate in adult patients with ADHD. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;255(6):428–431. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.La Fougère C, Krause J, Krause KH, et al. Value of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT to predict clinical response to methylphenidate treatment in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2006;27(9):733–737. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000230077.48480.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K, Ackenheil M. Stimulant-like action of nicotine on striatal dopamine transporter in the brain of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;5(2):111–113. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702002821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, Fischman AJ. Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet. 1999;354(9196):2132–2133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheon KA, Ryu YH, Kim YK, Namkoong K, Kim CH, Lee JD. Dopamine transporter density in the basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2003;30(2):306–311. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abi-Dargham A, Mawlawi O, Lombardo I, et al. Prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors and working memory in schizophrenia. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(9):3708–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okubo Y, Suhara T, Suzuki K, et al. Decreased prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in schizophrenia revealed by PET. Nature. 1997;385(6617):634–635. doi: 10.1038/385634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karlsson P, Farde L, Halldin C, Sedvall G. PET study of D1 dopamine receptor binding in neuroleptic-naive patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):761–767. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. The addicted human brain viewed in the light of imaging studies: brain circuits and treatment strategies. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(supplement 1):S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM, Telang F. Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(11):1575–1579. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM. Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results from imaging studies and treatment implications. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9(6):557–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Baler R, Telang F. Imaging dopamine’s role in drug abuse and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(supplement 1):S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Reinforcing effects of psychostimulants in humans are associated with increases in brain dopamine and occupancy of D2 receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;291(1):409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Prediction of reinforcing responses to psychostimulants in humans by brain dopamine D2 receptor levels. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1440–1443. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, et al. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386(6627):827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1993;14(2):169–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, et al. Low level of brain dopamine D2 receptors in methamphetamine abusers: association with metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2015–2021. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor availability in opiate-dependent subjects before and after naloxone-precipitated withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20(9):1594–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Volkow ND, Wang G, Fowler JS, et al. Therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate significantly increase extracellular dopamine in the human brain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(2) doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-j0001.2001. Article ID RC121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Relationship between blockade of dopamine transporters by oral methylphenidate and the increases in extracellular dopamine: therapeutic implications. Synapse. 2002;43(3):181–187. doi: 10.1002/syn.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Farde L, Pauli S, Hall H, et al. Stereoselective binding of 11C-raclopride in living human brain—a search for extrastriatal central D-2 dopamine receptors by PET. Psychopharmacology. 1988;94(4):471–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00212840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nord M, Farde L. Antipsychotic occupancy of dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2011;17(2):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kasper S, Tauscher J, Küfferle B, Barnas C, Pezawas L, Quiner S. Dopamine- and serotonin-receptors in schizophrenia: results of imaging-studies and implicationsfor pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1999;249(supplement 4):S83–S89. doi: 10.1007/pl00014189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, et al. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(14):8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tauscher J, Küfferle B, Asenbaum S, Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Kasper S. Striatal dopamine-2 receptor occupancy as measured with [123I]iodobenzamide and SPECT predicted the occurrence of EPS in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics and haloperidol. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162(1):42–49. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kasper S, Tauscher J, Küfferle E, Hesselmann B, Barnas C, Brücke T. IBZM-SPECT imaging of dopamine D2 receptors with typical and atypical antipsychotics. European Psychiatry. 1998;13(supplement 1):S9–S14. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)89488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Okamura N, Villemagne VL, Drago J, et al. In vivo measurement of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 density in Parkinson disease with 18F-AV-133. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(2):223–228. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Villemagne VL, Okamura N, Pejoska S, et al. In vivo assessment of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 in dementia with lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kung HF, Guo YZ, Billings J, et al. Preparation and biodistribution of [125I]IBZM: a potential CNS D-2 dopamine receptor imaging agent. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation B. 1988;15(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(88)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kung HF, Pan S, Kung MP, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of [123I]IBZM: a potential CNS D-2 dopamine receptor imaging agent. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1989;30(1):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pinborg LH, Videbaek C, Ziebell M, et al. [123I]epidepride binding to cerebellar dopamine D2/D3 receptors is displaceable: implications for the use of cerebellum as a reference region. Neuroimage. 2007;34(4):1450–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bohnen NI, Frey KA. Imaging of cholinergic and monoaminergic neurochemical changes in neurodegenerative disorders. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2007;9(4):243–257. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lu W, Wolf ME. Expression of dopamine transporter and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 mRNAs in rat midbrain after repeated amphetamine administration. Molecular Brain Research. 1997;49(1-2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin KJ, Weng YH, Wey SP, et al. Whole-body biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 18F-FP-(+) -DTBZ (18F-AV-133): a novel vesicular monoamine transporter 2 imaging agent. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(9):1480–1485. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.078196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology. 1999;56(1):33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tolosa E, Wenning G, Poewe W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pahwa R, Lyons KE. Early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease: recommendations from diagnostic clinical guidelines. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2010;16(supplement 4):S94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Blankson S, Lees AJ. A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 1993;50(2):140–148. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540020018011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rajput AH, Rozdilsky B, Rajput A. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinsonism—a prospective study. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1991;18(3):275–278. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100031814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Antonini A. Imaging for early differential diagnosis of parkinsonism. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(2):130–131. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Felicio AC, Shih MC, Godeiro-Junior C, Andrade LAF, Bressan RA, Ferraz HB. Molecular imaging studies in Parkinson disease reducing diagnostic uncertainty. Neurologist. 2009;15(1):6–16. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318183fdd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vlaar AMM, de Nijs T, Kessels AGH, et al. Diagnostic value of 123I-ioflupane and 123I- iodobenzamide SPECT scans in 248 patients with Parkinsonian syndromes. European Neurology. 2008;59(5):258–266. doi: 10.1159/000115640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thanvi B, Lo N, Robinson T. Vascular parkinsonism—an important cause of parkinsonism in older people. Age and Ageing. 2005;34(2):114–119. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Berry AL, Foltynie T. Gene therapy: a viable therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s disease? Journal of Neurology. 2010;258(2):179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Leriche L, Björklund T, Breysse N, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging demonstrates correlation between behavioral recovery and correction of dopamine neurotransmission after gene therapy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(5):1544–1553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4491-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson’s disease: an open label, phase I trial. The Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature. 1997;386(6627):830–833. doi: 10.1038/386830a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(6):456–463. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]