Abstract

The central nervous system is composed of the brain and the spinal cord. The brain is a complex organ that processes and coordinates activities of the body in bilaterian, higher-order animals. The development of the brain mirrors its complex function as it requires intricate genetic signalling at specific times, and deviations from this can lead to brain malformations such as anencephaly. Research into how the CNS is specified and patterned has been studied extensively in chick, fish, frog, and mice, but findings from the latter will be emphasised here as higher-order mammals show most similarity to the human brain. Specifically, we will focus on the embryonic development of an important forebrain structure, the striatum (also known as the dorsal striatum or neostriatum). Over the past decade, research on striatal development in mice has led to an influx of new information about the genes involved, but the precise orchestration between the genes, signalling molecules, and transcription factors remains unanswered. We aim to summarise what is known to date about the tightly controlled network of interacting genes that control striatal development. This paper will discuss early telencephalon patterning and dorsal ventral patterning with specific reference to the genes involved in striatal development.

1. Striatum: An Overview

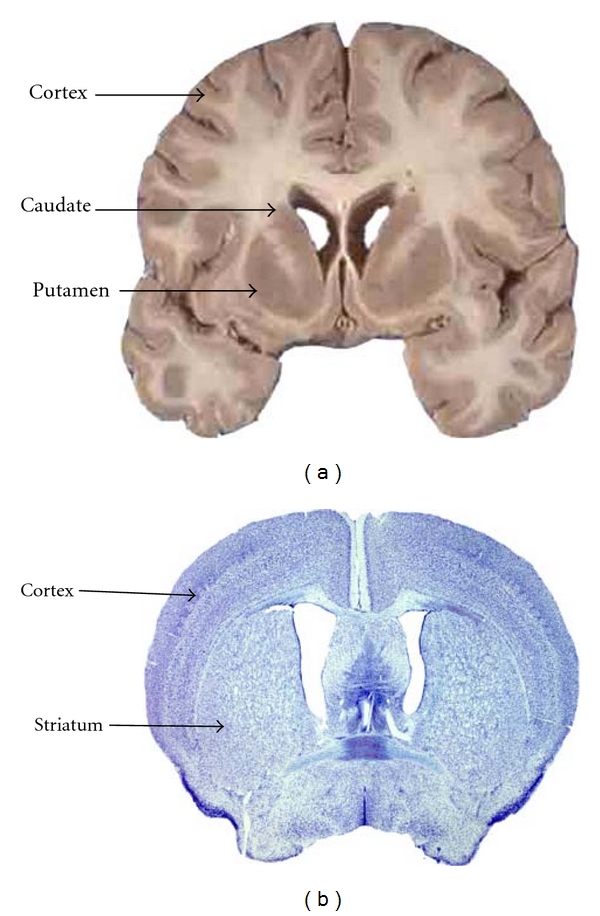

The striatum plays a vital role in the coordination of movement (primary motor control), emotions, and cognition [1–3]. In humans, the striatum is divided into two nuclei, the caudate and the putamen, by the internal capsule, whereas in mice it is one structure. This is shown in Figure 1. The complexity and importance of the striatum is best highlighted when it is impaired. There are a number of diseases that may produce striatal damage, including acquired conditions such as a stroke and genetically inherited conditions such as Huntington's disease (HD). HD is a condition that is characterised by neuronal dysfunction and neuronal loss that principally affects the medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the striatum. MSNs are the major projection neuron and constitute the vast majority of neurons in this structure. HD results in progressive deterioration of movement and cognition and, in many cases, additional behavioural deficits over a period of 15–30 years, and eventually renders an individual unable to care for themselves. To date there is little in the way of symptomatic treatment and no disease-modifying agents available. A better understanding of striatal development is likely to accelerate our understanding of the pathogenic processes underlying conditions such as HD and is central to the development of protocols to engineer stem cells to be suitable as donor tissue for cell replacement therapy [3–5].

Figure 1.

(a) Coronal section of a human brain showing the cortex, the caudate, and the putamen separately that when combined make up the striatum in comparison to (b) a caudal section of a mouse brain stained with cresyl violet showing the striatum as one structure and the cortex [1].

2. Neuronal Development

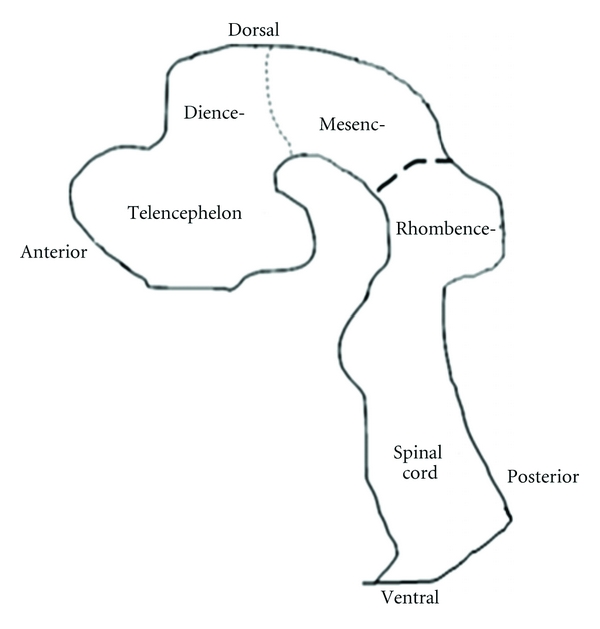

Development of the nervous system starts with neural induction, followed by neurulation that gives rise to the neural tube, and finally, patterning of this tube along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis. Following AP patterning, the neural tube folds and is subdivided into the prosencephalon (forebrain), the most anterior (rostral) part of the neural tube, which consists of the telencephalon and diencephalon, the mesencephalon (midbrain), and the rhombencephalon (hindbrain) [6]. These major subdivisions are shown in Figure 2. Regional patterning of the putative brain regions is then controlled by a series of interacting gene networks, of which the ones controlling telencephalic development are the most complex.

Figure 2.

Patterning of the neural tube. The neural plate folds to form the neural tube, which comprises developing areas of the CNS. The prosencephalon is split into the telencephalon and diencephalon and the mesencephalon and rhombencephalon.

3. Regional Patterning of the Developing Telencephalon

The embryonic telencephalon, which is located at the most rostral end of the neural tube, is divided into the dorsal telencephalon (also called pallium), which gives rise to the neocortex, and the ventral telencephalon (also called the subpallium), which forms the striatum and is the origin of cells that populate the olfactory bulb, globus pallidus (GP), and some cells that also populate the cortex [7]. This paper will concentrate on the development of the ventral telencephalon. Although the adult striatum is different between all mammalian species, the initial subdivisions observed in the telencephalon are comparable [8, 9].

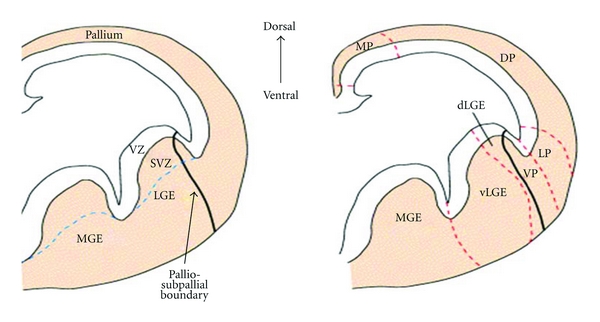

Due to the rapid migration of postmitotic neurons in the subpallium, three prominent intraventricular bulges form; the septum, the medial, and lateral ganglionic eminences (MGE/LGE), collectively referred to as the whole ganglionic eminence (WGE), shown in Figure 3. The MGE, the most ventral eminence, gives rise to the amygdaloid body and the GP whilst the LGE, that is situated more dorsally, gives rise to the caudate and putamen [10, 11]. The LGE is further divided into the dorsal LGE (dLGE) and the ventral LGE (vLGE) on the basis of regional gene expression, which is discussed later.

Figure 3.

Coronal hemisections of the mouse telencephalon at E12.5 showing morphologically defined structures and the progenitor subdomains. The ventricular zone (VZ) extends along the DV axis and contains proliferative neuronal precursor cells. The subventricular zone (SVZ) (shown by the blue dashed lines) also contains precursor cells. Progenitor cells migrate radially and tangentially from these zones to populate the specific areas of the brain. The dashed red lines indicate the approximate boundaries between distinct telencephalon progenitor domains. Abbreviations: MGE/LGE medial/lateral ganglionic eminence; MP: medial pallium, DP: dorsal pallium LP: lateral pallium, VP: ventral pallium. Picture taken from [15].

Within the surrounding neural epithelium of the developing telencephalon, there are two proliferative zones, which are shown in Figure 3, the ventricular zone (VZ), which is positioned on the perimeter of the lateral ventricles, and the subventricular zone (SVZ) (unique to the telencephalon), which extends from the basal region of the VZ [12]. It is in the proliferative zones of the ventral telencephelon that both projection neurons (including MSNs) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) interneurons are born before migrating to the regions they populate in the adult brain. Specifically, striatal projection neurons are born in the LGE and make up nearly 90% of LGE neurons. Interneurons originating from the LGE populate the cortex, olfactory bulb, and striatum, whereas those from the MGE migrate to the cortex, GP, and also the striatum [13–16].

4. Unzipping Telencephalon Development

The telencephalon is the most complex region of the mammalian brain and shows vast heterogeneity in terms of its various neuronal populations, structures, and function. Telencephalon development requires a variety of signals secreted from surrounding signalling centres to ensure the correct positional identity of the neurons, which will populate the adult forebrain. Several gene families are involved in coordinating the initial events for telencephalon patterning: principally fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), bone morphogenic proteins (Bmps), Wnts (originated from the drosophila gene wingless), retinoic acid (RA), and sonic hedgehog (Shh). These genes are responsible for activating downstream factors that enable signalling cascades to be initiated that allow cells to gain a positional and molecular identity [17]. It is likely that only a proportion of the factors required for neuronal identity have so far been identified, and the precise way in which such factors interact to specify the timing and terminal differentiation of particular neuronal subpopulations is not yet defined. However, there have been clear advances in knowledge in this area over the last few decades and we summarise here what is known about some of the key factors so far identified as being involved in striatal development.

5. FGF8

FGFs are ligands that activate several pathways, for example, Ras Map kinase (MAPK) pathway upon binding FGF receptors (FGFR) 1, 2, or 3 [18] and at least 5 FGF proteins have been indentified in CNS development [19]. Fgf8 is expressed rostrally from the anterior neural ridge (ANR) in mammals and has roles in proliferation and cell survival. In addition, it has been shown that Fgf8 regulates the expression of forkhead box protein G1 (FOXG1) (previously bf1), a rostral forebrain marker. It was shown that FGF8 could renew Foxg1 expression in mouse explants that had the ANR removed and secondly that inhibitors of Fgf8 reduced Foxg1 expression in neural plate explants [20, 21]. In addition, reduction in Fgf8 leads to rostral truncations and midline defects in the developing forebrain [22]. In Fgf8 null mice (Fgf8−/−), the telencephalon was smaller than in wild-type (WT) littermates and exhibited patterning abnormalities [22–24]. Specifically, loss of function studies showed that the MGE and LGE are absent, and there was loss of genes found in the ventral regions, for example, Nkx2.1 and Dlx2 and an expansion of the dorsal marker Pax6 [23]. These results suggest a role for Fgf8 in ventralisation of the telencephalon. However, it seems unlikely that Fgf8 is the sole factor involved in the induction of rostral forebrain development due to the continued presence of the telencephalon in Fgf8−/−or FGFR null mutants [22]. One explanation for the telencephalon still remaining in these mutants is that compensation is achieved by other Fgfs expressed at the same time. However, others in the field are of the opinion that overlapping Fgf expression profiles do not exist and that each Fgf has exclusive roles in telencephalon development [25, 26]. Therefore, the reason the telencephalon is not lost completely in the Fgf8 mutant is that Fgf8 alone is not essential for telencephelon generation [26, 27]. However, the fact that beads soaked in FGF8 added to anterior neural explants lacking an ANR promote expression of Foxg1 suggests FGFs are necessary for telencephalon induction [20].

Recently, work supporting the gain of function studies has allowed greater insight into the role of FGFs and FGFR in telencephalon development. Triple FGFR knockouts have shown that prior to telencephalon development at E10.5, embryos showed abnormalities in the anterior structures and by E12.5, a time when the telencephalic structures should be morphologically distinguishable, mutants lacked all anterior head structures and had no visible telencephalon except for the dorsal midline [19]. In addition, Foxg1 was not expressed, together with complete absence of the ventral markers Dlx2 and Nkx2.1. Unexpectedly, the dorsal marker Emx1 was also absent suggesting that FGF has a role in forming the dorsal telencephalon in addition to the ventral telencephalon [19].

The phenotype of the FGFR triple knockout was markedly more severe than the mild phenotype observed in single or double receptor mutants [18]. This supports the argument that these receptors do compensate for each other and do not have exclusive roles. However, this compensation is not absolute given that a mild phenotype was still evident in single or double mutants. This suggests the compensating receptors can function, but as they are not the first choice for the ligand, they produce signalling cascades at lower efficiencies [19]. Therefore, results from the different combinations of FGFR mutants suggest that the FGFR1 receptor is responsible for the majority of signalling, but it is the overall levels of FGF signalling that operate to initiate, pattern, and sustain early telencephalon development as a whole rather than specific ligands patterning different areas [19]. What is left to be answered is if the FGFs function as morphogens or independent to a concentration dependant gradient.

Foxg1 and Fgf8 are both expressed at approximately the same time in the ANR (~E8) and function through a tightly linked positive feedback loop [19, 20]. FGF signalling is sufficient and necessary for Foxg1 expression, and Foxg1 is necessary for Fgf8 expression [20]. However, the different phenotypes between Foxg1 mutants and the FGFR triple mutant suggest that both genes must function at least partially through independent genetic pathways, the details of which are still unknown [19].

6. SHH

SHH is a member of the hedgehog (Hh) family of secreted proteins and acts as a morphogen that is first secreted from the notochord, which underlies the posterior structures of the brain, following which expression is from the overlying neural plate [6, 27, 28]. By E9.5 Shh is expressed in neural epithelium of the ventral telencephelon [29], and by E12 it is expressed in the mantle zone and is no longer detectable in the neuroepithelium [30]. Shh operates through a concentration gradient that spans the DV axis at different time points to confer different neuronal identities on the developing precursors, and expression is first seen in the ventral telencenphelon from E11.5 [31, 32]. SHH expression directs neural progenitors to a ventral fate and importantly is both necessary and sufficient to induce specific ventral forebrain markers [32–34]. Shh is expressed in the ventral telencephalon and is thought to maintain Fgf8 expression [32, 35] as well as induce expression of forebrain markers. Specifically, SHH activates several TFs including Nkx2.1 [36, 37], Gsx2 (formerly Gsh2) [38–40], and Pax6 [41].

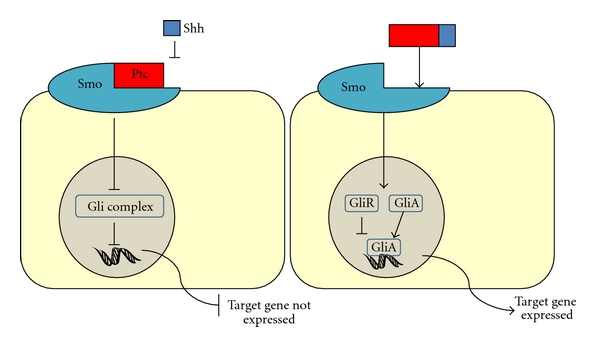

SHH acts as a ligand for a pathway involving two transmembrane proteins, patched (Ptc) and smoothened (Smo). Normally, Ptc is bound to Smo and the pathway is inactive as Smo is not free to activate the Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 3 (Gli3). This is illustrated in Figure 4. However, when SHH binds Ptc, Smo is de-repressed which results in the Gli repressor (GliR) becoming activated (GliA) and being able to translocate to the nucleus and activate gene expression, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The Shh pathway for target gene expression: (a) repressed pathway—when SHH cannot bind Ptc, ptc represses gene expression by being bound to Smo. Smo cannot then activate the Gli complex meaning the target gene is repressed. (b) Induction pathway—when SHH binds ptc, smo is released which allows the GliA to bind the DNA and activate gene expression. Abbreviations: SHH: sonic hedgehog, Ptc: patched, Smo: smoothened, GliA: Gli Activator.

There are three members of the Gli family of zinc- finger TFs, Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3 and all have been shown to regulate SHH-dependant gene expression. Gli proteins have both activator and repressor activities, the N-terminal encodes a repressor function, and the C-terminal region is required for positive activity [43]. It is believed that the Gli3 protein functions principally in its repressor form and it appears that its activity is negatively regulated by Shh [44, 45], whereas Gli1 and 2 function primarily as transcriptional activators [46, 47]. The negative regulation by Shh on Gli3 is observed in the limb, where Shh inhibits Gli3 from processing into its repressor form [43]. Analysis of mouse mutants for each of the Gli genes (Gli1−/−), Gli2−/−, and Gli3−/−) has shown that mice lacking Gli3 or Gli2 show only slight defects in telencephelon development [48], whereas mice lacking Gli3 have strong defects in dorsal telencephelon patterning [49–51]. At the dorsal region of the telencephelon, where the concentration of SHH is limited, the Gli3 protein is cleaved from an activator into a repressor form and promotes dorsal patterning [43]. It is the inhibition of the Gli3 repressor complex in the ventral region that facilities telencephalon development; therefore, the primary function of Shh is to prevent the production of excessive Gli repressors. However, as Gli3 has been shown to be able to function as a weak activator of Shh in vivo [52], the question recently investigated by Yu and colleagues [53] is whether this protein (or either Gli1 or 2) has an activating role in ventral telencephalon [53]. Recent work by this group suggests Gli activators do have a role in specification, differentiation, and positioning of some subgroups of telencephalon neuronal progenitors that arise from the interganglionic sulcus [53], but further experiments need to be carried out to learn more about the role of Gli proteins as activators, and therefore this paper will concentrate on the role of Gli3 as a repressor in DV patterning.

The relationship between Shh and Gli3 has been shown functionally through varying combinations of mutants. In Shh −/− mutants, the ventral markers Dlx2, and Gsx2 were reduced, whereas in Gli3−/− mutants the expression pattern of these genes was extended into more dorsal regions [43]. Overall the Shh −/− mutant shows more severe telencephelon abnormalities than the Gli3−/− mutant [49, 50]. In accord with the loss of ventral markers in Shh mutants (Shh−/−), there is a loss of ventral telencephalic cells leading to an altered morphology of the ventral telencephalon together with the ectopic expression of dorsal forebrain markers [33–35, 43]. Specifically, the mutants lack any MGE development as shown by the absence of Nkx2.1 [43]. In vitro, cultures of telencephalon explants treated with SHH result in expression of ventral markers such as Nkx2.1 [33]. The complimentary gain of function experiments carried out in both fish and mice has shown that SHH promotes ventral identity in dorsal telencephalic cells in vivo with induction of the ventral forebrain markers Gsx2, Dlx2 and Nkx2.1 [38, 54]. Importantly, conditional knockouts using a FoxG1-Cre to knock-out Shh have allowed the optimal window of signalling in telencephalon development to be investigated. Fuccillo et al. [55] showed that if Shh is knocked-out at E8.5, there are severe defects of all ventral telencephalic regions [55]. However, in knockouts at E10-12 using a Nestin-Cre, there are limited defects in ventral telencephalic patterning and cortical interneurons are affected rather than gross patterning deficits [56].

In the Shh−/− and Gli3−/+ mutants, telencephalon morphology is largely restored to WT, but regional gene expression is not fully restored. The ventral marker Nkx2.1 is not rescued unless both copies of the Gli3 protein are removed, suggesting Nkx2.1 is very sensitive to the antagonism between Shh and Gli3 [43]. Also, in Gli3−/− mutants, the expression of Nkx2.1 is not extended dorsally like Dlx2 and Gsx2, nor can it be expressed ectopically in the cortex when exogenous Shh is added. From this Rallu and colleagues suggested that the Gli2 protein has a complimentary role to Gli3. It is thought that Gli2 functions as a weaker repressor and can repress the expansion of Nkx2.1 in Gli3−/− mutants but is not strong enough to prevent the expansion of the more ventral genes Dlx2 and Gsx2 [43]. Moreover, in the Shh−/− and Gli3−/−, double mutant ventral markers such as Gsx2 and Dlx again were largely restored to WT levels [43, 57]. In support of this, Nkx2.1 expression was expanded in Ptc mutant mice (Ptc−/−). In this mutant, Smo should be persistently de-repressed and Gli proteins should remain in their activated form, thus having a repressive effect on Nkx2.1 expression in the MGE [58]. However, the fact that Dlx2 and Gsh2 were restored in the absence of Shh signalling in this mutant suggests that other genes and signalling pathways, independent to Shh signalling, have a role in DV patterning of the telencephalon [43].

In summary between E9 and E12.5, SHH acts mainly by inhibiting the formation of the Gli3 repressor [43] and contributes to the establishment of DV patterning [34, 55]. Secondly, SHH signalling also supports the expansion of progenitors of the ventral telencephalon by inducing and maintaining the expression of Nkx2.1 until at least E14 and later into neurogenesis [56].

7. Retinoic Acid

RA is the biologically active form of vitamin A and has been implicated in survival, specification, proliferation, and differentiation during forebrain development [58–60]. Two oxidation events occur to ensure RA is successfully derived to function as a ligand for either RA receptors (RARs) (RARα, RARβ and RARγ) or retinoid X receptors (RXRα, RXRβ, and RXRγ) that belong to the steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily [61]. Initially retinol dehydrogenases oxidate retinol to retinaldehyde and then the rate-limiting enzymes, retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (Raldh), are required to oxidate retinaldehyde to RA [62].

The first known source of RA in the developing striatum is in the LGE at approximately E12.5 and is produced from reactions mainly catalysed by Raldh3 [63]. It is not until E14 that RA and Raldh3 are obviously expressed in the LGE and promote GABAergic neuronal differentiation by inducing Gad67, an enzyme needed for GABA synthesis [64]. Raldh3 continues to promote GABAergic differentiation at E18.5, and RA continues to be expressed into adulthood [64]. It has also been reported that in vitro LGE-derived neurospheres and human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) induce GABAergic differentiation once RA was added to the media [64]. However, it is thought that the RA in the LGE is not only a product from Raldh3-mediated reactions as Raldh3−/− mutant mice do not show an obvious telencephalic phenotype [65]. It has been shown that retinoids from the glia found in the LGE are also functioning in striatal neuronal differentiation [66]; therefore, it is possible that these, and other sources not yet known could be compensating for Raldh3.

Furthermore, at this time the RARs α and β are present in the ventral telencephalon, with RARβ preferentially expressed in LGE together with RXRγ [67]. In RAR β −/− mutant mice, there is a loss of striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase mRNA, a gene regulated by RA in the striatum [67], and a reduction of striatal dopamine and cAMP-regulated protein (DARPP-32) positive neurons together with dynophin, μ-opioid receptor (MOR1), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) compared to WT mice [59, 67]. It has also been shown that when chick explants of LGE are treated with RAR antagonists, LGE specification is prevented [58]. The complimentary experiment shows that when exogenous RA was added to dorsal explants, LGE was evident instead of MGE [58]. Additionally, supplementation of RA to LGE cultures showed an increase in DARPP-32 positive neurons, whilst there was no effect seen in the MGE relevant to increasing doses of RA [66]. Moreover, blocking RA in chick embryos prevents the expression of Meis2 which is expressed in progenitor cells of the intermediate zone of the telencephalon and is the earliest known marker of striatal precursors [66]. Taken together, these results confirm the importance of RA in LGE specification.

As well as being important in embryonic development, RA expression remains in the forebrain throughout adult life and has been shown to maintain the expression of Fgf8 and Shh in this region, as when RA is removed, Fgf8 and Shh expression is lost [59, 60]. It has recently been proposed that Nolz1, a zinc finger TF that is expressed in the proliferative SVZ in LGE precursor cells, is implicated in RA signalling [68]. At E12.5 Nolz1-induced neurogenesis partially depends on RA signalling as it has been shown that this TF activates the RAR β receptor in LGE-derived neural precursor cells and that this effect was inhibited when RA was removed [68]. However, Nolz1 expression was not affected in Raldh3 mutant mice (Raldh3−/−), which lacks RA in the LGE, or when a vitamin A deficient diet was fed to the mothers [63, 69] suggesting RA is not essential to Nolz1 expression throughout development and is only needed to induce early expression. RA activates Nolz1 to induce initial neurogenesis during early striatal development at E12.5 but is not sufficient for its maintenance beyond this time [68]. Also, it has also been shown that Nolz1 contributes to later striatal development by working downstream of Gsx2 to activate the RARβ receptor.

8. Wnt Signalling

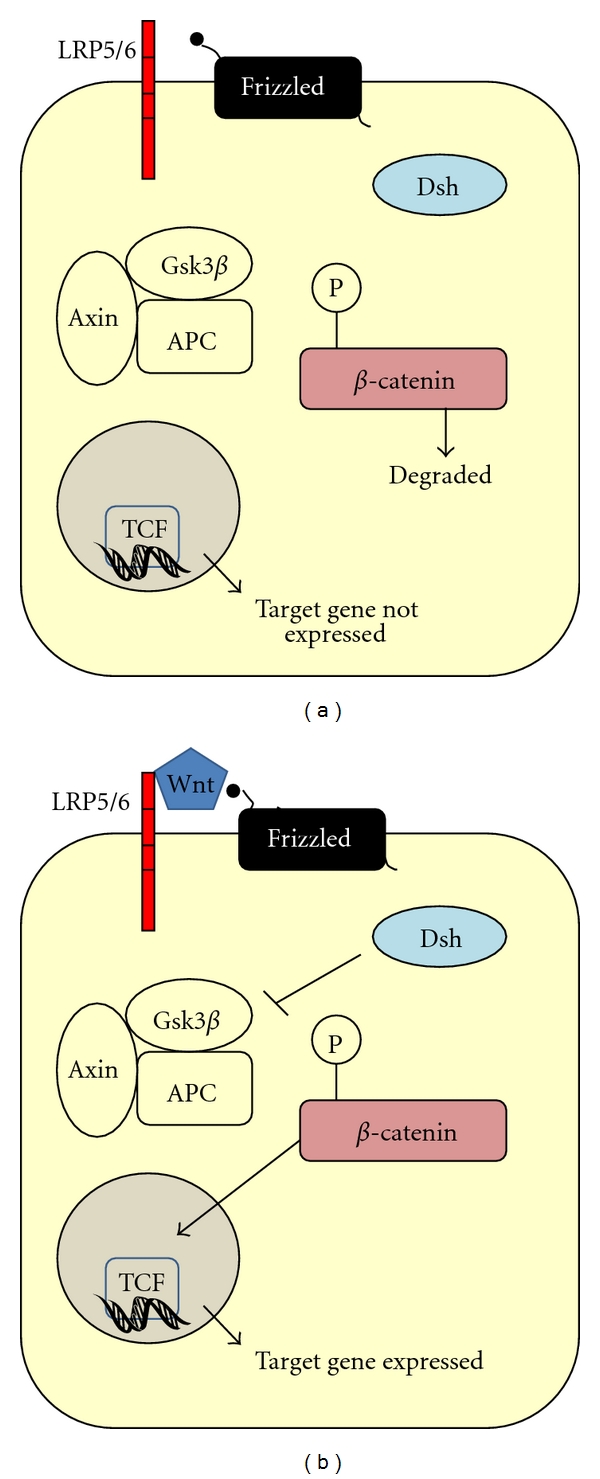

Wnts belong to the wingless protein family and are a class of ligands that are crucial in embryogenesis and have been implicated in CNS development. Wnts can signal through three different pathways: the canonical pathway, the planar cell polarity pathway, and the calcium pathway and it is the canonical pathway that is important in telencephalon development. In the canonical pathway, β-catenin is indirectly activated by a WNT ligand binding to the cell surface receptor, Frizzled. Upon binding, frizzled activates its intracellular component dishevelled (Dsh) that dephosphorylates β-catenin preventing its degradation by the axin-glycogen synthase kinas 3β (GSK3β) complex (in the absence of WNT signalling, β-catenin is phosphorylated by the GSK3β complex and degraded). β-catenin then translocates to the nucleus where it can activate the transcription of Wnt target genes such as T-cell factors (TCF), which in turn regulate genes such as c-myc. This pathway is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The canonical Wnt pathway for target gene expression. (a) When a WNT ligand is absent, β-catenin is phosphorylated by the Gsk3β complex and is targeted for degradation and there is no gene expression. (b) When a Wnt ligand binds Frizzled, Dsh is activated and inhibits the axin-Gsk3β complex phosphorylating β-catenin enabling it to translocate to the nucleus and can activate TCF which can activate gene expression. Abbreviations: APC: adenomatous polyposis coli, Dsh: Dishevelled; GSK3β: glycogen synthase kinase 3 β; TCF: T-cell factor.

Wnts are part of the cohort of caudalizing factors that are involved in the initial AP orientation of the neural plate and are crucial for the generation of the dorsal telencephelon [70]. Specific concentrations of WNTs are needed to further refine regional patterning and to induce the expression of Pax6, a dorsal telencephelon marker [71]. A reporter line carrying a LacZ reporter gene under the control of β-catenin/TCF response elements showed that WNT signalling is active in the pallium at E11.5 and E16.5 but not in the subpallium [72, 73]. In the absence of canonical signalling, there was ectopic expression of Gsx2, Dlx2, and Ascl1 (formerly Mash1) in dorsal telencephelon together with downregulation of the dorsal markers Emx1, 2 and 3 [73]. This ectopic expression of ventral genes facilitated the cells of the dorsal telencephelon to adopt a ventral fate, therefore allowing these cells to have the potential to become GABAergic projection neurons [73]. Therefore, this work in mice has shown that WNT signalling is necessary for ensuring the correct molecular characterisation, and thus morphology, of the dorsal telencephelon before the onset of neurogenesis and that inhibition of WNT signalling is necessary for subpallidal development [73]. In addition, gain of function experiments carried out in chicks has shown the importance of Wnt gene expression in dorsal telencephelon patterning. Using chick explant cultures, Gunhaga et al. [71] showed that Wnt3a or Wnt8 expression can convert the ventral telencephalic cells into Pax6 and Ngn2 positive cells at the expense of Ascl1 and Nkx2.1 [71].

9. BMPs

Although BMP inhibition is required for neuronal development, graded concentrations are necessary in the neural plate to establish medial-to-lateral patterning [42]. BMPs belong to the TGFβ family of secreted proteins. It is thought that BMPs are also needed to dorsalize the telencephalon and restrict ventral telencephalic development. Forebrain patterning was repressed in forebrain explant cultures when BMPs were added as shown by inhibition of Foxg1, Nkx2.1, and Dlx2 [74]. Similarly beads soaked in BMP4 or BMP5 that were implanted into the neural tube of a chick forebrain induced dorsal markers, for example, Wnt4 and repressed ventral markers [75]. Additionally, when the telencephalic roof plate (a source of BMPs) was ablated, there was a reduction in cortical size and a decrease of one of the most dorsal cortical markers, Lhx2 [76]. BMPs are inhibited by several factors including chordin and noggin. In mice that lacked both copies of the chordin gene (chordin −/−) and one copy of the noggin gene (noggin +/−), a dorsal, rather than ventral telencephalon was evident. However, this effect may not be direct because of an increase in BMP and may be in part due to the decreased levels of Shh and Fgf8 expression in the forebrain caused by increased BMP levels [77].

10. Foxg1

Foxg1 is a member of the winged helix family of TFs and is the earliest recognised marker of the telencephalon [78]. This TF was first identified in the rat brain, where it was shown that its expression was restricted to the telencephelon [78]. By E8.5 Foxg1 is expressed in the neural tube, specifically in the anterior plate cells that are fated to contribute to the telencephalon [20, 79], and functions to establish and subdivide the telencephalon.

Foxg1−/− mutant mice show no morphological differences in the size of the developing telencephalon at E10.5. However, the ventral markers Ascl1, Nkx2.1, Gsx2, and Dlx1/2 are absent, and instead the dorsal markers, Emx2 and Pax6, are expressed throughout the telencephelon [80, 81]. It has also been shown that Fgf8 was reduced in the mutant telencephalon at E10.5 [81]. By E12.5 there were considerable morphological differences in the ventral telencephalon of the mutant when compared to WT; notably the GEs were absent but there were no defects in the dorsal area [80, 81]. A reason for the absence of the ventral telencephalon in these mutants is the loss of proliferating cells in this region (shown through BrdU staining) with telencephalic proliferation being restricted to the dorsal region [80]. This decrease in proliferation could be a direct consequence of the lack of Foxg1 expression or could be due to effectors of Foxg1 not being able to function optimally.

It has also been shown that Foxg1 coordinates signalling pathways of SHH and WNTs, which are required for the development of the subpallial and pallial telencephalon, respectively, and have been described above [82]. Dorsal identity is prevented by Foxg1 inhibiting the Wnt pathway, further confirming the role of Foxg1 in ventral telencephalon induction in an independent way to SHH. Manuel et al. [17] cultured cells from Foxg1−/− mice and showed that the addition of SHH and FGF8 alone could not induce the expression of other ventral telencephalon genes. Also, further experiments where Foxg1−/− cells were grafted into Foxg1−/− / Foxg1+/+chimeras, showed that the mutant cells, were specified abnormally, did not integrate with WT cells and expressed dorsal rather than ventral markers [17]. Recently, Manuel et al. [83] have also shown that the reason for mutant cells behaving differently is due to them having an increased cell cycle, something initially reported by Martynoga et al. [81]. Specifically, Manuel and colleagues have shown that this is due to a decrease in Pax6 expression, a cell cycle organiser. Upon addition of PAX6, the mutant phenotype was partially rescued [83]. This work suggests that Foxg1 not only promotes the production of ventralising cues, but has a cell autonomous role in regulating Pax6 [83]. Foxg1 is crucial in forebrain development and is absolutely required for the regulation of telencephalic identity.

11. Dorsoventral (DV) Organisation of the Developing Telencephalon

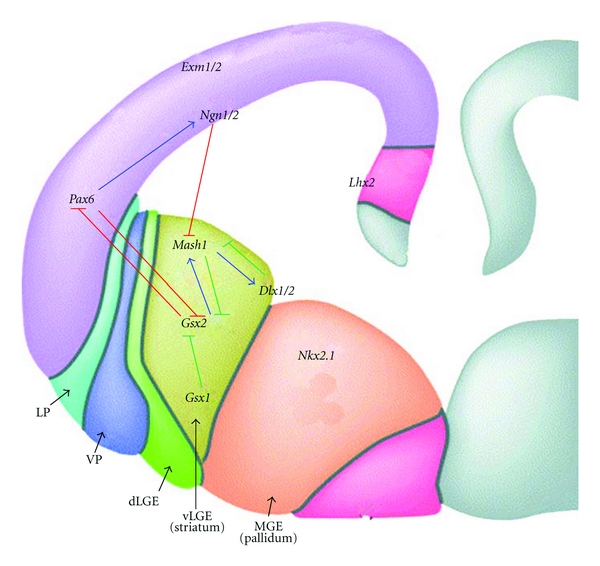

As discussed already, the developing telencephalon is divided into the dorsal region, and the ventral region and these areas can be defined on a morphological and genetic basis. In the dorsal telencephalon Pax6, Neurogenin (Ngn) 1/2 and Emx1/2 are expressed; in the ventral telencephalon, Gsx2, Asc1, Dlx1/2, and Nkx2.1 are expressed, as shown in Figure 6 [84]. The pallial genes will only be discussed briefly in the context of them as markers, not to fully elucidate their role in cortical development. Emx1/2 expression profiles are restricted to the most dorsal region of the cortex with no expression seen in the ventral cortical region. Ngn 1 and 2 are basic helix loop helix (bHLH) TFs which are expressed throughout the cortex together with Pax6. In the absence of Ngn expression, Ascl1 is ectopically expressed in the dorsal telencephalon thus priming these cells to adopt a ventral fate and becoming GABAergic rather than glutamatergic neurons. Therefore, the role of Ngn1/2 is to maintain the DV boundary in the developing telencephalon and to inhibit ventral gene expression such as Ascl1 [24, 85].

Figure 6.

Schematic coronal section through the developing telencephalon at E12.5—the dorsal and ventral subdomains are shown and defined by unique gene expression patterns. Dorsal telencephalic markers shown are Emx1/2, Ngn1/1, and Pax6. The ventral telencephalic markers shown can be split into identifying the LGE or MGE. Mash1(Ascl1), Gsx1/2, and Dlx1/2 are associated with the LGE (specifically the vLGE), and Nkx2.1 is associated with the MGE. Some of the gene interactions are shown on the diagram. One of the important interactions is between Pax6 and Gsx2; these genes work together to ensure the subpallalial/pallial border is maintained. Arrows denote positive interactions; T-bars denote inhibitory control. The green arrows represent the genetic signalling that has been unravelled in more recent data and occurs at later time points. Figure adapted from [42].

Homeodomain gene interactions are crucial in mediating DV patterning and importantly, in setting up regional subdivisions within the developing telencephalon, as well as within the ventral telencephelon, and are principally regulated through Shh [36–41]. Pax6 and Gsx2 are two members of this homeodomain family [86]. These proteins have overlapping expression profiles and work in synergy to ensure the subpallium-pallium border is maintained [39]. Their expression profiles mirror each other; Pax6 is expressed in a dorsal (high) to ventral (low) gradient and Gsx2 is expressed in a ventral (high) to dorsal (low) gradient [87].

The embryonic patterning role of Pax6 was initially identified through genetic mapping of the classical “small eye” (sey) mouse mutant [88]. Pax6 is needed for cortical development and to establish the subpallial-pallial border and is initially detected in the developing forebrain at E8 [89]. It is not until the neural tube stage that expression is downregulated in ventral regions simultaneous with the up regulation of Nkx2.1 in this region, thus instantaneously setting up the DV ventral border on the basis of differential gene expression [37, 38, 90]. In Pax6 mutant mice (Pax6−/−), there is a shift in the cortical-striatal boundary [91] and the cortical markers Ngn1/2 and Emx1 are downregulated, and Dlx1/2 [39, 41, 92], Ascl11 [39, 41] and Gsx2 [39] are ectopically expressed in dorsal regions of the telencephalon. Nkx2.1 also expands dorsally into the LGE shifting the LGE-MGE border [41].

Gsx2 is first detected in the developing forebrain between E9 and E10 and is expressed in the LGE. Gsx2 mutants (Gsx2−/−) have the opposite phenotype to that seen in Pax6 mutants; there is ectopic expression of Pax6 and Ngn2 in the LGE accompanied by the loss of Ascl1 and Dlx2 [38–40]. On the whole, there was a reduction in the size of the LGE at E12 [93], which by E18.5 led to a reduction in the size of the striatum [94] and reduced expression of striatal projection neurons confirmed through a marked decrease in DARPP-32 and the earlier MSN marker, Forkhead box P1 (FoxP1) [38–40, 95]. However, there was a slight increase in the striatal-matrix marker calbindin [95]. These results suggest that Gsx2 is a crucial inducer of Ascl1, Dlx1, and Dlx2 whilst repressing dorsal character and is implicated in the differentiation of calbindin positive neurons. However, in mice that lack both Gsx2 and Pax6 (Gsx2−/− and Pax6−/−), the phenotype observed was more subtle than the single mutations as is the case in Shh −/− Gli3−/− double mutants [38]. This suggests that other genes are also important in mediating DV patterning and positioning of the pallial-subpallial boundary.

Gsx1, a gene closely related to Gsx2, is also expressed in the ventral telencephalon but unlike Gsx2 its expression is restricted to the ventral most region of the LGE [96]. It is thought that Gsx1 can partially compensate for the phenotype observed in Gsx2−/− mutants [95, 97, 98]. In the Gsx2−/− mutant, Gsx1 expression spreads throughout the LGE between E11 and E14.5 and shows similar expression patterns to Ascl1 in the LGE [95]. DARPP-32 expression is lost in both Gsx2−/− /Ascl1− /− and Gsx2−/− Gsx1−/− double mutants suggesting Ascl1 has a role in regulating Gsx1 to compensate for Gsx2 in Gsx2−/− mutants [95]. Until recently the role of Gsx1 has remained elusive as no phenotype has been discovered through using knockouts. Pei et al. [99] have shown that Gsx1 and Gsx2 differentially regulate the maturation of LGE progenitors. Gain-of-function experiments were carried out to distinguish if these two closely linked genes do indeed carry out different roles in the LGE or if Gsx1 is simply a “backup” for Gsx2. Results showed that Gsx2 maintains LGE progenitors in an undifferentiated position before Gsx1, in part through the downregulation of Gsx2, directs the progenitors to acquire a mature neuronal phenotype [99]. This is shown in Figure 6. These novel results indicate that the Gsx genes regulate LGE patterning through a controlled balance of signalling allowing proliferation and differentiation of neuronal progenitors [99].

Ascl1 is also a member of the bHLH family of TFs. It has a primary role in the correct development of the ventral telencephalon and relies on Gsx2 for normal expression [38–40, 100]. In contrast to Ngn1/2 that is expressed in the dorsal telencephelon, Ascl1 is expressed throughout the ventral telencephalon and ASCL1 protein is seen in the VZ and SVZ, where neuronal precursor cells reside [101]. When Ascl1 was ectopically expressed in the dorsal telencephalon, it was able to induce neurons to express Dlx1/2 at the expense of cortical markers [24]. Ascl1 interacts with Dlx1/2 that in turn activates GAD/67, the rate-limiting enzyme for GABAergic synthesis, and the two combined function to facilitate GABAergic differentiation in the telencephalon [85, 100]. However, in Ascl1 knockout experiments (Ascl1−/−), Dlx and Gad/67 are still expressed in the ventral telencephelon [100]. Together with the fact that these developing neurons can still acquire a GABAergic phenotype in the absence of Dlx1 and 2, this suggests an element of redundancy in this signalling pathway and/or the involvement of other genes not yet identified. Expression of Gsx2 in the Ascl1−/− mutant is the same at E12.5, but by E18.5 there is an increase in Gsx2 expressing cells suggesting that Ascl1 has the additional role of repressing Gsx2 function later in development. This is shown in Figure 6 [94]. Ascl1−/− mutants also show a reduction in the number of early born striatal (cholinergic) and cortical (GABAergic) interneurons and a reduction in size of the MGE [100]. This phenotype can be explained by the initial loss of precursor cells in the SVZ, subsequently leads to a decrease in neurons populating the mantle zone [100, 102]. Conversely, TH, D2R, and enkephalin positive neurons are only slightly reduced in this mutant. This is expected considering the LGE is only partially reduced [102]. However, Wang et al. [94] suggest that the reason for the Ascl1 mutant not giving a more severe phenotype is that Gsx2 signals through another bHLH TF.

From these experiments, it can be concluded that Ascl1 has the dual role of specifying precursors and controlling the timing of their differentiation, principally in the MGE and possibly has a role in the LGE, although it is not crucial in this later eminence [98, 102]. Recent experiments by Castro and colleagues have looked more closely into the precise mechanisms by which Ascl1 controls proliferation of neuronal precursors [103]. Gene expression analysis carried out from embryonic brains and neural stem cell cultures showed that Ascl1 has a role in regulating genes concerned with cell cycle progression and ultimately showed that there was a direct association between neural progenitor expansion and the corresponding phases of cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation [103]. What is clear is that Ascl1 is autonomously involved in patterning of early telencephalic progenitors (~E10.5) and nonautonomously involved in repressing the differentiation of adjacent progenitors through Notch signalling [100]. After Ascl1 has been expressed to aid neurogenesis, Dlx1 and 2 repress Ascl1 and subsequent notch signalling to promote terminal neuronal differentiation [104].

The Dlx family bears homology to the drosophila distal less-homeobox gene family of which there are 6 murine members, 4 of which are expressed in the developing MGE and LGE [105]. Dlx1 and Dlx2 are expressed by subsets of cells in the VZ and by most cells in the SVZ and switch off as cells start to differentiate [101, 106]. Dlx5 and Dlx6 are expressed in the SVZ and mantle zone only [13]. Single mutations of Dlx1 or 2 show no noticeable forebrain defects; although in the absence of both Dlx1 and 2; there is arrested migration of matrix neurons within the SVZ [13, 106]. However, striatal development is not stopped completely, and this phenotype suggests other genes are involved in neuronal migration or that other genes such as Gsx2 and Ascl1 are compensating somehow by directly activating the targets of Dlx1 and 2. A series of experiments from Rubenstein's lab have sought to identify other genes and TFs that could function downstream and upstream of Dlx1/2 to control LGE specification and differentiation through a series of gene expression arrays and in situ hybridisations [107]. It is likely that further work will continue to find relationships between these genes and Dlx1 and 2.

As mentioned above, Dlx1 and 2 activate GAD67, an enzyme needed for GABA synthesis and found in neuronal precursors of the SVZ and neurons of the mantle zone in the ventral telencephalon [100], and in Dlx1/2− /− there are decreased levels of GAD67 in the dLGE [108]. It is has been suggested that Dlx1/2 indirectly activate GAD67 and that cooperation with other proteins is needed to promote a GABA neuronal phenotype [109]. Necidin is a maternally imprinted gene and is only expressed in the paternal allele [110, 111]. Mutant mice that lacked the paternal necidin allele showed a significant decrease in the differentiation of GABAergic neurons in vivo and in vitro, therefore suggesting that necidin facilitates the specification of GABAergic neurons in cooperation with Dlx proteins [109].

Nkx2.1 is expressed exclusively in the MGE and is another homedomain protein. The primary role of Nkx2.1 is in ventral specification of the telencephalon where it acts to repress LGE identity, and it is also important in the development of striatal interneurons [7, 37]. Nkx2.1 is induced by Shh at E8 [33], and as earlier mentioned, inhibition of Shh leads to reduced expression of Nkx2.1 and dorsalisation of the ventral embryo [34]. In the Nkx2.1 mutant mouse (Nkx2.1−/−), there are a lack of MGE derivatives and a DV switch of the MGE as it shows properties similar to the LGE rather than the MGE, for example some cells have been shown to express DARPP-32 [37]. The loss of Nkx2.1 also showed a reduction of GABA and calbindin positive neurons from the cortex [37]. Additionally, generation of an (Nkx2.1−/−) mouse with the addition of a DlxtauLacZ reporter gene showed loss of early migration of Dlx2-expressing progenitors [30].

It is clear that DV patterning of the telencephelon requires the precise orchestration of several genes and TFs that work together to ensure the correct development of the striatum. It is likely that further experiments using the ever expanding range of genetic tools will further disclose the roles of genes already known, further elucidate the signalling pathways they operate through, and identify novel genes that have a functional role in striatal development and that can be used as specific regional markers [112–114].

12. Conclusion

This paper has aimed to summarise and organise research that is being carried out to understand the genetic mechanisms controlling striatal development. However, it is clear that there are still many pieces of the jigsaw to be found and fitted into the gaps of this puzzle. The more that is known about the development of the striatum, and, importantly, the development and differentiation of striatal MSN neurons, the more precise the protocols can be to direct the fate of renewable cell sources, such as embryonic stem cells, to a functional MSN phenotype for use in cell replacement therapy for HD. An additional aspiration is to identify specific genes to detect MSN precursors rather than relying on markers of terminally differentiated MSNs, such as DARPP-32. Earlier markers of putative MSNs could be used to facilitate the generation and refinement of neuronal differentiation protocols as well as tracking neuronal differentiation in grafts.

References

- 1.Bates G, Harper PS, Jones L. Huntigton's Disease. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser RA, Furtado S, Cimino CR, et al. Bilateral human fetal striatal transplantation in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 2002;58(5):687–695. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization. Trends in Neurosciences. 1992;15(4):133–139. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90355-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly CM, Dunnett SB, Rosser AE. Medium spiny neurons for transplantation in Huntington’s disease. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2009;37(1):323–328. doi: 10.1042/BST0370323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachoud-Lévi AC, Gaura V, Brugières P, et al. Effect of fetal neural transplants in patients with Huntington’s disease 6 years after surgery: a long-term follow-up study. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(4):303–309. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubenstein JLR, Shimamura K, Martinez S, Puelles L. Regionalization of the prosencephalic neural plate. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1998;21:445–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain M, Armstrong RJE, Barker RA, Rosser AE. Cellular and molecular aspects of striatal development. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;55(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez AS, Pieau C, Repérant J, Boncinelli E, Wassef M. Expression of the Emx-1 and Dlx-1 homeobox genes define three molecularly distinct domains in the telencephalon of mouse, chick, turtle and frog embryos: implications for the evolution of telencephalic subdivisions in amniotes. Development. 1998;125(11):2099–2111. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puelles L, Kuwana E, Puelles E, et al. Pallial and subpallial derivatives in the embryonic chick and mouse telencephalon, traced by the expression of the genes Dlx-2, Emx-1, Nkx-2.1, Pax-6, and Tbr-1. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;424(3):409–438. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000828)424:3<409::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturrock RR. A comparative quantitative and morphological study of ageing in the mouse neostriatum, indusium griseum and anterior commissure. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 1980;6(1):51–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1980.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deacon TW, Pakzaban P, Isacson O. The lateral ganglionic eminence is the origin of cells committed to striatal phenotypes: neural transplantation and developmental evidence. Brain Research. 1994;668(1-2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell K. Dorsal-ventral patterning in the mammalian telencephalon. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2003;13(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson SA, Qiu M, Bulfone A, et al. Mutations of the homeobox genes Dlx-1 and Dlx-2 disrupt the striatal subventricular zone and differentiation of late born striatal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell K, Olsson M, Björklund A. Regional incorporation and site-specific differentiation of striatal precursors transplanted to the embryonic forebrain ventricle. Neuron. 1995;15(6):1259–1273. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson M, Björklund A, Campbell K. Early specification of striatal projection neurons and interneuronal subtypes in the lateral and medial ganglionic eminence. Neuroscience. 1998;84(3):867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Rahilly R, Muller F. The Embryonic Human Brain: An Atlas of Development Stages. New York, NY, USA: Wiley-Liss; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manuel M, Martynoga B, Yu T, West JD, Mason JO, Price DJ. The transcription factor Foxg1 regulates the competence of telencephalic cells to adopt subpallial fates in mice. Development. 2010;137(3):487–497. doi: 10.1242/dev.039800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason I. Initiation to end point: the multiple roles of fibroblast growth factors in neural development. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(8):583–596. doi: 10.1038/nrn2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paek H, Gutin G, Hébert JM. FGF signaling is strictly required to maintain early telencephalic precursor cell survival. Development. 2009;136(14):2457–2465. doi: 10.1242/dev.032656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimamura K, Rubenstein JLR. Inductive interactions direct early regionalization of the mouse forebrain. Development. 1997;124(14):2709–2718. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye W, Shimamura K, Rubenstein JLR, Hynes MA, Rosenthal A. FGF and Shh signals control dopaminergic and serotonergic cell fate in the anterior neural plate. Cell. 1998;93(5):755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanmugalingam S, Houart C, Picker A, et al. Ace/Fgf8 is required for forebrain commissure formation and patterning of the telencephalon. Development. 2000;127(12):2549–2561. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Storm EE, Garel S, Borello U, et al. Dose-dependent functions fo Fgf8 in regulating telencephalic patterning centers. Development. 2006;133(9):1831–1844. doi: 10.1242/dev.02324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson SW, Rubenstein JLR. Induction and dorsoventral patterning of the telencephalon. Neuron. 2000;28(3):641–651. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cholfin JA, Rubenstein JLR. Frontal cortex subdivision patterning is coordinately regulated by Fgf8, Fgf17, and Emx2. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;509(2):144–155. doi: 10.1002/cne.21709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borello U, Cobos I, Long JE, Murre C, Rubenstein JLR. FGF15 promotes neurogenesis and opposes FGF8 function during neocortical development. Neural Development. 2008;3(1, article 17) doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Echelard Y, Epstein DJ, St-Jacques B, et al. Sonic hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity. Cell. 1993;75(7):1417–1430. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roelink H, Porter JA, Chiang C, et al. Floor plate and motor neuron induction by different concentrations of the amino-terminal cleavage product of sonic hedgehog autoproteolysis. Cell. 1995;81(3):445–455. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimamura K, Hartigan DJ, Martinez S, Puelles L, Rubenstein JLR. Longitudinal organization of the anterior neural plate and neural tube. Development. 1995;121(12):3923–3933. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nery S, Corbin JG, Fishell G. Dlx2 progenitor migration in wild type and Nkx2.1 Mutant telencephalon. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13(9):895–903. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.9.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jessell TM. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2000;1(1):20–29. doi: 10.1038/35049541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohtz JD, Baker DP, Corte G, Fishell G. Regionalization within the mammalian telencephalon is mediated by changes in responsiveness to Sonic Hedgehog. Development. 1998;125(24):5079–5089. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ericson J, Muhr J, Placzek M, Lints T, Jessell TM, Edlund T. Sonic hedgehog induces the differentiation of ventral forebrain neurons: a common signal for ventral patterning within the neural tube. Cell. 1995;81(5):747–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, et al. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383(6599):407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohkubo Y, Chiang C, Rubenstein JLR. Coordinate regulation and synergistic actions of BMP4, SHH and FGF8 in the rostral prosencephalon regulate morphogenesis of the telencephalic and optic vesicles. Neuroscience. 2002;111(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00616-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura S, Hara Y, Pineau T, et al. The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain, and pituitary. Genes and Development. 1996;10(1):60–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JLR. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126(15):3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbin JG, Gaiano N, Machold RP, Langston A, Fishell G. The Gsh2 homeodomain gene controls multiple aspects of telencephalic development. Development. 2000;127(23):5007–5020. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toresson H, Potter SS, Campbell K. Genetic control of dorsal-ventral identity in the telencephalon: opposing roles for Pax6 and Gsh2. Development. 2000;127(20):4361–4371. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.20.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun K, Potter S, Rubenstein JLR. Gsh2 and Pax6 play complementary roles in dorsoventral patterning of the mammalian telencephalon. Development. 2001;128(2):193–205. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoykova A, Treichel D, Hallonet M, Gruss P. Pax6 modulates the dorsoventral patterning of the mammalian telencephalon. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(21):8042–8050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08042.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson SW, Houart C. Early steps in the development of the forebrain. Developmental Cell. 2004;6(2):167–181. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rallu M, Machold R, Gaiano N, Corbin JG, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Dorsoventral patterning is established in the telencephalon of mutants lacking both Gli3 and hedgehog signaling. Development. 2002;129(21):4963–4974. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marigo V, Johnson RL, Vortkamp A, Tabin CJ. Sonic hedgehog differentially regulates expression of GLI and GLI3 during limb development. Developmental Biology. 1996;180(1):273–283. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B, Fallon JF, Beachy PA. Hedgehog-regulated processing of Gli3 produces an anterior/posterior repressor gradient in the developing vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;100(4):423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai CB, Joyner AL. Gli1 can rescue the in vivo function of Gli2. Development. 2001;128(24):5161–5172. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dai P, Akimaru H, Tanaka Y, Maekawa T, Nakafuku M, Ishii S. Sonic hedgehog-induced activation of the Gli1 promoter is mediated by GLI3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(12):8143–8152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park HL, Bai C, Platt KA, et al. Mouse Gli1 mutants are viable but have defects in SHH signaling in combination with a Gli2 mutation. Development. 2000;127(8):1593–1605. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grove EA, Tole S, Limon J, Yip LW, Ragsdale CW. The hem of the embryonic cerebral cortex is defined by the expression of multiple Wnt genes and is compromised in Gli3-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125(12):2315–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Theil T, Alvarez-Bolado G, Walter A, Rüther U. Gli3 is required for Emx gene expression during dorsal telencephalon development. Development. 1999;126(16):3561–3571. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tole S, Ragsdale CW, Grove EA. Dorsoventral patterning of the telencephalon is disrupted in the mouse mutant extra-toes. Developmental Biology. 2000;217(2):254–265. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai CB, Stephen D, Joyner AL. All mouse ventral spinal cord patterning by Hedgehog is Gli dependent and involves an activator function of Gli3. Developmental Cell. 2004;6(1):103–115. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu W, Wang Y, McDonnell K, Stephen D, Bai CB. Patterning of ventral telencephalon requires positive function of Gli transcription factors. Developmental Biology. 2009;334(1):264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaiano N, Kohtz JD, Turnbull DH, Fishell G. A method for rapid gain-of-function studies in the mouse embryonic nervous system. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2(9):812–819. doi: 10.1038/12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuccillo M, Rallu M, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Temporal requirement for hedgehog signaling in ventral telencephalic patterning. Development. 2004;131(20):5031–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.01349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu Q, Wonders CP, Anderson SA. Sonic hedgehog maintains the identity of cortical interneuron progenitors in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 2005;132(22):4987–4998. doi: 10.1242/dev.02090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulacsi A, Anderson SA. Shh maintains Nkx2.1 in the MGE by a Gli3-independent mechanism. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:i89–95. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marklund M, Sjödal M, Beehler BC, Jessell TM, Edlund T, Gunhaga L. Retinoic acid signalling specifies intermediate character in the developing telencephalon. Development. 2004;131(17):4323–4332. doi: 10.1242/dev.01308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider RA, Hu D, Rubenstein JLR, Maden M, Helms JA. Local retinoid signaling coordinates forebrain and facial morphogenesis by maintaining FGF8 and SHH. Development. 2001;128(14):2755–2767. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haskell GT, LaMantia AS. Retinoic acid signaling identifies a distinct precursor population in the developing and adult forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(33):7636–7647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0485-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Function of retinoid nuclear receptors: lessons from genetic and pharmacological dissections of the retinoic acid signaling pathway during mouse embryogenesis. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2006;46:451–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134(6):921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molotkova N, Molotkov A, Duester G. Role of retinoic acid during forebrain development begins late when Raldh3 generates retinoic acid in the ventral subventricular zone. Developmental Biology. 2007;303(2):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chatzi C, Brade T, Duester G. Retinoic acid functions as a key gabaergic differentiation signal in the basal ganglia. PLoS Biology. 2011;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000609. Article ID e1000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dupé V, Matt N, Garnier JM, Chambon P, Mark M, Ghyselinck NB. A newborn lethal defect due to inactivation of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 3 is prevented by maternal retinoic acid treatment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(2):14036–14041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336223100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toresson H, De Urquiza AM, Fagerström C, Perlmann T, Campbell K. Retinoids are produced by glia in the lateral ganglionic eminence and regulate striatal neuron differentiation. Development. 1999;126(6):1317–1326. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liao WL, Liu FC. RARβ isoform-specific regulation of DARPP-32 gene expression: an ectopic expression study in the developing rat telencephalon. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21(12):3262–3268. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urbán N, Martín-Ibáñez R, Herranz C, et al. Nolz1 promotes striatal neurogenesis through the regulation of retinoic acid signaling. Neural Development. 2010;5(1, article 21) doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verma AK, Shoemaker A, Simsiman R, Denning M, Zachman RD. Expression of retinoic acid nuclear receptors and tissue transglutaminase is altered in various tissues of rats fed a vitamin A-deficient diet. Journal of Nutrition. 1992;122(11):2144–2152. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houart C, Caneparo L, Heisenberg CP, Barth KA, Take-Uchi M, Wilson SW. Establishment of the telencephalon during gastrulation by local antagonism of Wnt signaling. Neuron. 2002;35(2):255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gunhaga L, Marklund M, Sjödal M, Hsieh JC, Jessell TM, Edlund T. Specification of dorsal telencephalic character by sequential Wnt and FGF signaling. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6(7):701–707. doi: 10.1038/nn1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maretto S, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, et al. Mapping Wnt/β-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(6):3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Backman M, Machon O, Mygland L, et al. Effects of canonical Wnt signaling on dorso-ventral specification of the mouse telencephalon. Developmental Biology. 2005;279(1):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Furuta Y, Piston DW, Hogan BLM. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) as regulators of dorsal forebrain development. Development. 1997;124(11):2203–2212. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Golden JA, Bracilovic A, Mcfadden KA, Beesley JS, Rubenstein JLR, Grinspan JB. Ectopic bone morphogenetic proteins 5 and 4 in the chicken forebrain lead to cyclopia and holoprosencephaly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(5):2439–2444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Monuki ES, Porter FD, Walsh CA. Patterning of the dorsal telencephalon and cerebral cortex by a roof plate-lhx2 pathway. Neuron. 2001;32(4):591–604. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson RM, Lawrence AR, Stottmann RW, Bachiller D, Klingensmith J. Chordin and noggin promote organizing centers of forebrain development in the mouse. Development. 2002;129(21):4975–4987. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tao W, Lai E. Telencephalon-restricted expression of BF-1, a new member of the HNF- 3/fork head gene family, in the developing rat brain. Neuron. 1992;8(5):957–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hébert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Developmental Biology. 2000;222(2):296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xuan S, Baptista CA, Balas G, Tao W, Soares VC, Lai E. Winged helix transcription factor BF-1 is essential for the development of the cerebral hemispheres. Neuron. 1995;14(6):1141–1152. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martynoga B, Morrison H, Price DJ, Mason JO. Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Developmental Biology. 2005;283(1):113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Danesin C, Peres JN, Johansson M, et al. Integration of telencephalic Wnt and hedgehog signaling center activities by Foxg1. Developmental Cell. 2009;16(4):576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Manuel MN, Martynoga B, Molinek MD, et al. The transcription factor Foxg1 regulates telencephalic progenitor proliferation cell autonomously, in part by controlling Pax6 expression levels. Neural Development. 2011;6(1, article 9) doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schuurmans C, Guillemot F. Molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate specification in the developing telencephalon. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2002;12(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fode C, Ma Q, Casarosa S, Ang SL, Anderson DJ, Guillemot F. A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes and Development. 2000;14(1):67–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hsieh-Li HM, Witte DP, Szucsik JC, Weinstein M, Li H, Potter SS. Gsh-2, a murine homeobox gene expressed in the developing brain. Mechanisms of Development. 1995;50(2-3):177–186. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00334-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hébert JM, Fishell G. The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: some assembly required. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9(9):678–685. doi: 10.1038/nrn2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hill RE, Favor J, Hogan BLM, et al. Mouse small eye results from mutations in a paired-like homeobox-containing gene. Nature. 1991;354(6354):522–525. doi: 10.1038/354522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stoykova A, Gruss P. Roles of Pax-genes in developing and adult brain as suggested by expression patterns. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(3):1395–1412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01395.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crossley PH, Martinez S, Ohkubo Y, Rubenstein JLR. Coordinate expression of Fgf8, Otx2, Bmp4, and Shh in the rostral prosencephalon during development of the telencephalic and optic vesicles. Neuroscience. 2001;108(2):183–206. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stoykova A, Götz M, Gruss P, Price J. Pax6-dependent regulation of adhesive patterning, R-cadherin expression and boundary formation in developing forebrain. Development. 1997;124(19):3765–3777. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stoykova A, Fritsch R, Walther C, Gruss P. Forebrain patterning defects in small eye mutant mice. Development. 1996;122(11):3453–3465. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Szucsik JC, Witte DP, Li H, Pixley SK, Small KM, Potter SS. Altered forebrain and hindbrain development in mice mutant for the Gsh- 2 homeobox gene. Developmental Biology. 1997;191(2):230–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang B, Waclaw RR, Allen ZJ, Guillemot F, Campbell K. Ascl1 is a required downstream effector of Gsx gene function in the embryonic mouse telencephalon. Neural Development. 2009;4(1, article 5) doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang RM, Zhang QG, Li J, Yang LC, Yang F, Brann DW. The ERK5-MEF2C transcription factor pathway contributes to anti-apoptotic effect of cerebral ischemia preconditioning in the hippocampal CA1 region of rats. Brain Research. 2009;1255(C):32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Valerius MT, Li H, Stock JL, et al. Gsh-l: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in the central nervous system. Developmental Dynamics. 1995;203(3):337–351. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Toresson H, Campbell K. A role Gsh1 in the developing striatum and olfactory bulb of Gsh2 mutant mice. Development. 2001;128(23):4769–4780. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.23.4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yun K, Garel S, Fischman S, Rubenstein JLR. Patterning of the lateral ganglionic eminence by the Gsh1 and Gsh2 homeobox genes regulates striatal and olfactory bulb histogenesis and the growth of axons through the basal ganglia. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003;461(2):151–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.10685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pei Z, Wang B, Chen G, Nagao M, Nakafuku M, Campbell K. Homeobox genes Gsx1 and Gsx2 differentially regulate telencephalic progenitor maturation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(4):1675–1680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008824108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Casarosa S, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 regulates neurogenesis in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 1999;126(3):525–534. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Porteus MH, Bulfone A, Liu JK, Puelles L, Lo LC, Rubenstein JLR. DLX-2, MASH-1, and MAP-2 expression and bromodeoxyuridine incorporation define molecularly distinct cell populations in the embryonic mouse forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(11 I):6370–6383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marín O, Anderson SA, Rubenstein JLR. Origin and molecular specification of striatal interneurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(16):6063–6076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06063.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Castro DS, Martynoga B, Parras C, et al. A novel function of the proneural factor Ascl1 in progenitor proliferation identified by genome-wide characterization of its targets. Genes and Development. 2011;25(9):930–945. doi: 10.1101/gad.627811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yun K, Fischman S, Johnson J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Weinsmaster G, Rubenstein JLR. Modulation of the notch signalling by Mash1 and Dlx1/2 regulates sequential specification and differentiation of progenitor cell types in the subcortical telencephalon. Development. 2002;129(21):5029–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu JK, Ghattas I, Liu S, Chen S, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx genes encode DNA-binding proteins that are expressed in an overlapping and sequential pattern during basal ganglia differentiation. Developmental Dynamics. 1997;210(4):498–512. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199712)210:4<498::AID-AJA12>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nery S, Wichterle H, Fishell G. Sonic hedgehog contributes to oligodendrocyte specification in the mammalian forebrain. Development. 2001;128(4):527–540. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Long JE, Swan C, Liang WS, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx1&2 and Mash1 transcription factors control striatal patterning and differentiation through parallel and overlapping pathways. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2009;512(4):556–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.21854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Long JE, Garel S, Alvarez-Dolado M, et al. Dlx-dependent and -independent regulation of olfactory bulb interneuron differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(12):3230–3243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5265-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuwajima T, Nishimura I, Yoshikawa K. Necdin promotes GABAergic neuron differentiation in cooperation with Dlx homeodomain proteins. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(20):5383–5392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1262-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jay P, Rougeulle C, Massacrier A, et al. The human NECDIN gene, NDN, is maternally imprinted and located in the Prader-Willi syndrome chromosomal region. Nature Genetics. 1997;17(3):357–361. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.MacDonald HR, Wevrick R. The necdin gene is deleted in Prader-Willi syndrome and is imprinted in human and mouse. Human Molecular Genetics. 1997;6(11):1873–1878. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arlotta P, Molyneaux BJ, Chen J, Inoue J, Kominami R, MacKlis JD. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45(2):207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Martín-Ibáñez R, Crespo E, Urbán N, et al. Ikaros-1 couples cell cycle arrest of late striatal precursors with neurogenesis of enkephalinergic neurons. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2010;518(3):329–351. doi: 10.1002/cne.22215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tamura S, Morikawa Y, Iwanishi H, Hisaoka T, Senba E. Foxp1 gene expression in projection neurons of the mouse striatum. Neuroscience. 2004;124(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]