Abstract

Dengue, endemic in Puerto Rico, reached a record high in 2010. To inform policy makers, we derived annual economic cost. We assessed direct and indirect costs of hospitalized and ambulatory dengue illness in 2010 dollars through surveillance data and interviews with 100 laboratory-confirmed dengue patients treated in 2008–2010. We corrected for underreporting by using setting-specific expansion factors. Work absenteeism because of a dengue episode exceeded the absenteeism for an episode of influenza or acute otitis media. From 2002 to 2010, the aggregate annual cost of dengue illness averaged $38.7 million, of which 70% was for adults (age 15+ years). Hospitalized patients accounted for 63% of the cost of dengue illness, and fatal cases represented an additional 17%. Households funded 48% of dengue illness cost, the government funded 24%, insurance funded 22%, and employers funded 7%. Including dengue surveillance and vector control activities, the overall annual cost of dengue was $46.45 million ($12.47 per capita).

Introduction

Dengue fever, or break bone fever, is an infectious tropical diseasedisease transmitted to humans through bites of infected Aedes mosquitos, principally Ae. aegypti.1 Dengue has been increasingly recognized as a major global public health concern since the 1950s.2,3 It is endemic in more than 100 countries and is expanding to new regions, including Africa and West Asia,4–6 with nearly 3 billion people at risk of infection.7 The World Health Organization (WHO) reported a 30-fold increase in dengue incidence over the past 50 years.6 After adjusting for underreporting, an estimated 100 to 200 million dengue infections, 34 million cases of dengue fever, 2 million cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever, and 20,000 dengue deaths occur yearly,8–10 making dengue the most important vector-borne viral disease of humans.8

The emergence of dengue has resulted in considerable threats to population health and caused substantial costs.11–13 A dynamic disease with a wide clinical spectrum that ranges from an asymptomatic infection to a self-limiting febrile illness to severe dengue and to a life-threatening condition characterized by extensive capillary permeability and shock,5,6 dengue is considered the world's most rapidly spreading mosquito borne illness.14,15

Dengue is a flavivirus virus with four different antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV1–DENV4).16,17 Infection with one dengue virus serotype provides lifelong immunity to reinfection by the homologous serotype.18 However, cross-protection heterotypic immunity typically lasts from 2 weeks to 3 months,19 but thereafter, individuals infected with one serotype are fully susceptible to infection with other types; these subsequent infections may be accompanied by increased severity of the disease.16,18 One factor leading to severe dengue is “antibody-mediated immune enhancement, where antibodies developed from a previous infection cause enhanced viral uptake with a new infection of a different serotype.”20,21 Other factors relate to the person's genetic risk, the strain and serotype of the infecting virus, the degree of viremia, and immune pathology.5,9,22,23

Currently, there is no specific medication or antibiotic to treat dengue.1,5,14 For non-severe minor febrile cases, treatment includes relief of symptoms, rest, and adequate hydration. Because the disease may progress rapidly, careful management is needed, sometimes requiring hospitalization. Dengue hemorrhagic fever requires continued monitoring of vital signs and urine output, whereas dengue shock syndrome is considered a medical emergency that requires intensive care unit hospitalization.4,6

Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, is one of the few areas within the United States with substantial dengue transmission.24 According to the Dengue Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Puerto Rico, 61,844 suspected dengue cases were reported between 2002 and 2010.25 Of these cases, 22,648 cases were confirmed dengue cases, with nearly 1.6% (N = 350) having dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). In 2010, Puerto Rico declared an epidemic of dengue with its largest ever outbreak of over 21,000 suspected dengue cases, of which 46% were laboratory confirmed with a general infection rate of 24.94 per 10,000.25 Because mild cases are often not reported, the incidence in 2010 was probably several times higher.26

Currently, the only available control strategies are reducing mosquito abundance, reducing adult mosquito lifespan, and preventing mosquito–human contact.13,14 The CDC Dengue Branch, the Puerto Rico Department of Health, and larger municipalities maintain surveillance systems to monitor the epidemic of dengue, inform policy makers, and recommend control measures.27 Puerto Rico law requires reporting all cases of dengue fever and DHF in both ambulatory and hospitalized settings.25,28 Physicians are given special training to improve the diagnosis and treatment of dengue.28 Through mass media and educational campaigns, citizens are educated on prevention of dengue and control of vectors.27,29 Larger municipalities and the Puerto Rico Department of Health conduct vector programs using recommended guidelines.13,30

Costs for dengue treatment are incurred not only by the government but also by insurers, employers, patients, and their families. The 1977 dengue epidemic in Puerto Rico cost $6.16 million for medical treatment and prevention,31 and the 1994 epidemic cost $12 million for medical treatment alone.32 However, as numbers of suspected dengue cases have been escalating, with evidence of increasing disease severity30 and substantial variation among years (from a low of 3,162 in 2002 to a high of 21,319 in 2010),25 more research summarizing the numbers of cases and costs of treatment over a series of years is needed for a more comprehensive picture.

To address the variability of dengue cases and cost across years, this paper estimates the annual average aggregate economic costs of treated dengue cases in Puerto Rico during the period of 2002 through 2010. We use data collected from multiple sources, including patients, insurers, and clinicians, combined with the results of our previous study on costs of dengue surveillance and vector control,27 and incorporate sensitivity analyses.

Methods

Sample selection.

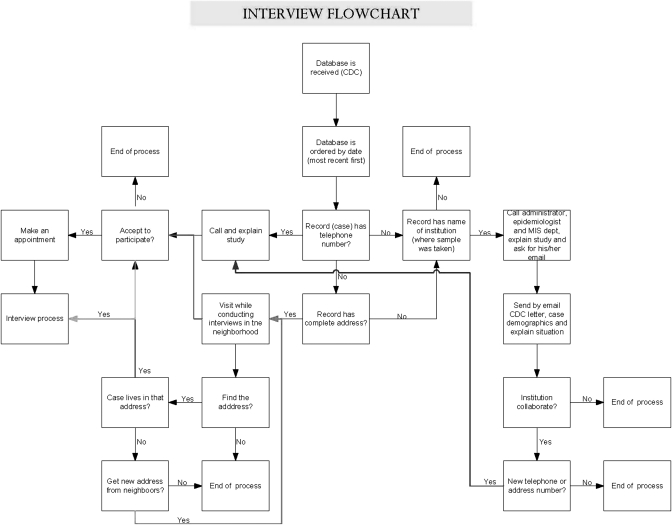

Working from the compulsorily reported dengue cases33 during the prospective study period of July of 2008 through March of 2010, the CDC Dengue Branch provided the study interviewers with a password-protected list of laboratory-confirmed dengue patients who met the WHO clinical case definition of dengue.34 For each case, CDC staff and the study interviewers contacted the facility where the patient sought care to request patient's contact information. Public health officials then contacted the patient to update his/her contact information and obtain their consent for future interviews when they were fully recovered from the dengue episode. Appendix 1 describes the study's sampling and enrollment processes. The final sample consisted of 100 laboratory-confirmed dengue patients who had an episode of dengue during the period of 2008–2010, consisting of 44 children (i.e., patients < 15 years; 31 hospitalized and 13 received ambulatory care) and 56 adults (i.e., patients aged 15+ years; 36 hospitalized and 20 received ambulatory care).

Cost of non-fatal ambulatory and hospitalized cases.

The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at Brandeis University and the CDC reviewed and approved the research protocol. After receiving patients' or legal surrogates' consents for the interview and access to medical and insurance records, the study interviewer contacted each patient (or parent) at the time of the patient's full recovery from the illness episode. The interviewers followed a structured questionnaire adapted from a previous study,12 which was previously validated on a prospective sample of dengue hospitalized and ambulatory patients, that was programmed into a handheld device (personal data assistant) with QDS software and translated into Spanish. The software's automated branching and cross-referencing validated responses and obviated most coding and data entry. The survey instrument measured patients' qualities of life during a dengue episode, duration of illness, use of medical services, dengue impact on schooling, work productivity, and leisure time, out of pocket illness-related payments, and income lost as well as the time and income loss of caretakers because of the patient's illness. Standard routines for cleaning, consistency checks, and analysis were performed.

Cost analysis framework.

The direct medical cost captures the payments by insurers, government, employers, and households (including copayment and deductibles, if any) for medical services and prescriptions. For hospitalized cases, payments by insurers were compiled from insurance companies and/or hospital financial departments. For ambulatory cases, out-of-pocket payments, number of visits, and types of settings were obtained from patients during the interview, whereas insurance payments were obtained from insurers. Payments were imputed for 7 of 100 patients where actual amounts were not available through any source. The imputation was based on other patients in the study with similar age, days of sickness, severity, number of ambulatory visits, type of provider, and number of hospitalized days (including the number of days spent at the intensive care unit [ICU]). Some hospitalized patients received ambulatory care in addition to inpatient care, which was often not reflected in hospital bills or insurance claims. For the cost of ambulatory treatment, we used insurance and facility-level data as well as patients' estimates of the cost of the ambulatory medical services received and associated charges (e.g., prescription charges and other out of pocket payments) through the interviews. We estimated the actual payments for ambulatory services as 70% of their median charges based on the ratio under the government health insurance plan, which covers most of the island's population.35 For 61 hospitalized subjects, we were able to validate self-reported data on days of hospitalization using administrative data from hospitals and insurers. We calculated the ratio of the self-reported number to the number shown in insurance and hospital records and computed the mean and 95% confidence interval.

Direct non-medical cost represents expenses for transportation, meals, and lodging while seeking care during the dengue episode; this information was obtained during patient interviews. Indirect cost consists of the opportunity cost associated with days of schooling lost for children and working days lost for both patients and caregivers because of illness. Although it was not possible to access school and work records to confirm absenteeism from work or school, our validation of self-reported length of stay indicated that respondents generally reported their illness accurately. For school children, the duration of illness and the number of days absent from school were obtained from the interviews. The cost of $42.75 per day of schooling (derived by dividing the annual budget of the Puerto Rico Department of Education by Puerto Rico school enrollment according to the US Census Bureau36) was used to calculate the economic cost of schooling lost because of the illness episode. For adults, the duration of illness and the number of days absent from work, if any, were obtained through the interview. The minimum daily wage of $49.2037 was used to estimate the opportunity cost of absence from work. Similarly, we asked whether patients had any caregivers during their illness. If the caregivers were paid, we obtained the amount paid directly from the interview. If caregivers were not paid for their services (e.g., family members), we asked patients to estimate the days of care provided by caregivers, and we estimated the costs of care using the aforementioned minimum daily wage.

Projection of annual number of dengue cases.

The number of laboratory-positive confirmed dengue cases between 2002 and 2010 was obtained from the CDC's Dengue Branch in Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rico Department of Health. To adjust for underreporting, we used an expansion factor of 2.42 for hospitalized and fatal cases and 10 for ambulatory cases.38 The work by Meltzer and others39 estimated expansion factors of 10–27 to project the number of dengue cases based on reported cases through 1994.39,40 We chose the lower bound for ambulatory cases, because dengue awareness has increased; additionally, Puerto Rico's dengue surveillance system has strengthened appreciably from 1994 to 2010.28,29,41 Our expansion factor for fatal cases is consistent with a recent study showing that enhanced surveillance of deaths from acute fever episodes revealed a substantial number of dengue deaths not previously recognized.42

Cost of fatal dengue cases.

We assumed that the fatal cases will be severe cases treated at hospitals and will have the same age distribution as hospitalized cases. We estimated the cost of fatal dengue as the economic value of the years lost from premature death caused by dengue. We estimated the average age of children who died prematurely because of dengue to be 8 years and the average age for adults who died prematurely because of dengue to be 32 years. We calculated their years of life lost as the sum of their discounted (at an annual rate of 3%) remaining life expectancy at their age of death based on the US Social Security Administration's period life table.43 Then, we multiplied the average discounted years by Puerto Rico's gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for 2010.40 Because most fatal cases die within 4 or 5 days of illness,42 we estimated the aggregate cost of fatal cases as the cost of premature death because of dengue in addition to the direct medical and non-medical costs and indirect cost of an average cost of a hospitalized case. Reported dengue deaths represented 0.36% of hospitalized cases (annual average of 16 deaths per 4,431 cases).

Projection of annual cost of dengue.

The total cost for each of the six categories of cases (child hospitalized [ambulatory and death] and adult hospitalized [ambulatory and death]) was estimated by multiplying the average cost per case by the projected number of these cases. The overall cost was computed using the weighted average cost of child and adult patients using projected numbers of cases. The cost was further broken down by financing agent categories (insurer, household, government, and employer), type of cost (direct medical cost, direct non-medical cost, and indirect cost), and type of care (hospitalization and ambulatory care). All costs were standardized to 2010 US dollars.

Uncertainty of total cost estimation and sensitivity analysis.

After we calculated the treatment cost for each case, we bootstrapped all types of treatment costs, including the aggregate cost, with 10,000 repetitions and generated a 95% confidence interval (CI) of the dengue illness cost. The bootstrapping was conducted using MATLAB 2009b (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) for hospitalized and ambulatory cases only. We used various expansion factors to estimate the number of dengue cases in Puerto Rico.31,39,44 These factors vary inversely with the severity of the epidemic under study and the quality of the surveillance and reporting systems. Our sensitivity analyses examined a range of expansion factors for ambulatory care ranging from 5 to 27 based on our literature review.39

Results

Table 1 shows the reported and projected average number of ambulatory and hospitalized dengue cases as well as the average number of fatal dengue cases (included in the hospitalized cases) for the years 2002 through 2010.

Table 1.

Average annual number of reported laboratory-positive dengue and projected dengue cases and the average fatal cases between 2002 and 2010

| Age group | Hospitalized | Ambulatory | Total | Fatal* | Row (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported cases | |||||

| Children < 15 years | 566 | 146 | 712 | 2 | 29 |

| Adults 15+ years | 1,265 | 445 | 1,710 | 5 | 71 |

| Total | 1,831 | 591 | 2,422 | 7 | 100 |

| Projected cases | |||||

| Children < 15 years | 1,370 | 1,460 | 2,830 | 5 | 27 |

| Adults 15+ years | 3,061 | 4,450 | 7,511 | 11 | 73 |

| Total | 4,431 | 5,910 | 10,341 | 16 | 100 |

Fatal cases are included in the number of hospitalized cases.

The projection of hospitalized and fatal cases uses an expansion factor of 2.42 from a laboratory-based capture/recapture surveillance system for Puerto Rico (average of 1991–1995). Ambulatory cases use the lower bound of 10 from the range in the work by Meltzer et al.39

On average, hospitalized patients averaged 4.5 days in hospital (3.9 days in a ward and 0.6 day in ICU). Our validation of self-reported length of stay found that self-reported hospitalized nights agreed reasonably well with the number shown in administrative data. The average ratio was 1.16, with a 95% CI of 1.05 to 1.26. Table 2 shows the average cost per dengue case by age group and types of cost and care as well as the average days affected from a dengue episode by age group. The average costs per hospitalized case and per ambulatory case were similar between children and adults. Children tended to have higher direct medical costs than adults, but the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, hospitalized adults had much higher indirect costs (P < 0.05), which compensated for their lower direct costs. The direct nonmedical cost was higher for children in both hospitalized (P < 0.01) and ambulatory (P < 0.05) settings. In ambulatory care, indirect costs were the major component of a dengue episode cost, constituting 62% and 71% of the total cost in child and adult dengue cases, respectively. We also found that the cost of the dengue treatment varied greatly among patients. The coefficients of variation for child and adult hospitalized cases were 57% and 51%, respectively, and for child and adult ambulatory cases were 45% and 56%, respectively. The average cost per death was $428,559 overall, being $474,712 for a child death and $407,903 for an adult death.

Table 2.

Average cost per adult and child case by setting and type of cost and days affected by a dengue episode from 2002 to 2010

| Setting and type of cost | Children | Adults | All | t Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized (total) | $5,387 | $5,518 | $5,497 | −0.18 |

| Direct medical cost | $4,031 | $3,515 | $3,687 | 0.90 |

| Direct non-medical cost | $187 | $123 | $144 | 2.69* |

| Indirect costs | $1,170 | $1,880 | $1,666 | −2.29† |

| Ambulatory (total) | $1,236 | $1,293 | $1,279 | −0.24 |

| Direct medical cost | $425 | $358 | $375 | 1.00 |

| Direct non-medical cost | $39 | $19 | $24 | 2.47* |

| Indirect costs | $773 | $916 | $880 | −0.58 |

| Fatal (indirect cost)‡ | $474,712 | $407,903 | $432,188 | na |

| All settings | $4,075 | $3,604 | $3,733 | na |

| Days affected (patient and caregivers) | ||||

| School- and work-related absenteeism | 6.5 | 8.3 | 7.2 | −0.99 |

| Work absenteeism | 4.3 | 6.9 | 5.3 | −1.64 |

| Total affected | 30.9 | 29.9 | 30.5 | 0.31 |

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

The fatal indirect cost indicates the cost of premature death from dengue.

na = not applicable.

In general, the average days of a patient's school and work absenteeism were 7.2 days, of which 5.3 days were days of work absenteeism. Time lost because of caregiving raised the number of affected days because of a dengue episode to 30.5 days. We found no statistically significant differences between children and adults.

Table 3 shows the cost per case by age group and source of financing. In absolute costs, households incurred a higher financial burden for an adult hospitalized dengue patient compared with a hospitalized child dengue case (P < 0.05). The pattern for ambulatory cases was similar but not statistically significant. Households paid 21% of the total cost for child hospitalized dengue cases and 37% for adult hospitalized cases. In the ambulatory setting, households accounted for 51% of total cost for a child with dengue and 63% for an adult with dengue. The government paid about 30% and 29% of hospitalized dengue cases costs for child and adult cases, respectively. For ambulatory cases, the government paid a larger amount for the treatment of child dengue cases (29% compared with 16% for adult cases). Among fatal dengue cases, households bore 89.8% of the total indirect cost, whereas the government incurred 10.2% of the total indirect cost as lost tax revenues.45

Table 3.

Average cost per child and adult case by setting and financing source from 2002 to 2010

| Setting and financing source | Child | Adult | All | t Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized (non-fatal) | $5,387 | $5,518 | $5,497 | −0.18 |

| Insurance | $2,353 | $1,487 | $1,761 | 1.45 |

| Households | $1,156 | $2,027 | $1,764 | −2.29* |

| Employers | $285 | $387 | $357 | −0.97 |

| Government | $1,593 | $1,616 | $1,615 | −0.04 |

| Ambulatory | $1,236 | $1,293 | $1,279 | −0.24 |

| Insurance | $102 | $105 | $104 | −0.04 |

| Households | $627 | $809 | $764 | −0.82 |

| Employers | $154 | $178 | $172 | −0.26 |

| Government | $353 | $202 | $239 | 1.89 |

| Fatal† | $474,712 | $407,903 | $432,188 | – |

| Insurance | – | – | $0 | – |

| Households | $426,291 | $366,297 | $388,063 | – |

| Employers | – | – | $0 | – |

| Government | $48,421 | $41,606 | $44,063 | – |

P < 0.05.

The cost of fatal cases represents the indirect cost of premature death from dengue. This cost represents the discounted cost of the Puerto Rican GDP per capita and is shared by both households (89.8%) and the government (10.2%).

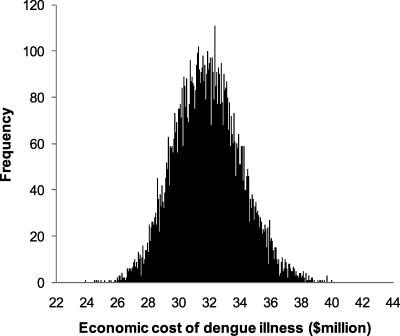

Table 4 shows the aggregate cost of treated dengue cases based on the projected number of dengue cases from Table 1. Our analysis estimated an annual aggregate dengue illness cost of $38.7 million in Puerto Rico, equivalent to $10.40 per capita per year. Of all the illness cost, children represented 30%, whereas adults constituted the remaining 70% (not shown in the table); 63% of illness cost was incurred by hospitalized patients, 20% of illness cost was incurred by ambulatory cases, and 18% of illness cost was incurred by the indirect cost of fatal cases. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of estimated total treatment cost of dengue. The CI shows that the total treatment cost of dengue was estimated between $28.1 and $36.5 million, which is equivalent to $7.54–9.80 per capita in 2010.

Table 4.

Aggregate annual cost of projected dengue case by setting, type of cost, source of financing, and result of the bootstrapping with 95% CI of the dengue illness cost from 2002 to 2010 (in thousands of 2010 US dollars)

| Type or source | Hospitalized | Ambulatory | Fatal | Total | SE* | 95% CI | Col. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower* | Upper* | |||||||

| Breakdown by type of cost | ||||||||

| Direct medical costs | $16,280 | $2,215 | $1 | $18,495 | $1,591 | $16 | $21,976 | 48 |

| Direct non-medical costs | $634 | $141 | $0 | $775 | $62 | $1 | $916 | 2 |

| Indirect costs | $7,356 | $5,203 | $6,914 | $19,474 | $1,248 | $11 | $15,509 | 50 |

| Total | $24,270 | $7,559 | $6,915 | $38,744 | $2,148 | $28,101 | $36,508 | 100 |

| Breakdown by source of financing | ||||||||

| Insurance | $7,775 | $616 | $0 | $8,392 | $1,354 | $6,033 | $11,437 | 22 |

| Households | $7,789 | $4,516 | $6,209 | $18,514 | $1,337 | $10,008 | $15,365 | 48 |

| Employers | $1,575 | $1,015 | $0 | $2,590 | $413 | $1,914 | $3,597 | 7 |

| Government | $7,131 | $1,413 | $705 | $9,248 | $1,440 | $6,203 | $12,026 | 24 |

| Total | $24,270 | $7,559 | $6,915 | $38,744 | $2,148 | $28,101 | $36,508 | 100 |

| Row (%) | 63 | 20 | 18 | 100 | ||||

These values were obtained through the bootstrapping analysis for ambulatory and hospitalized cases only. They do not include the indirect cost of fatal cases because of premature death.

The cost of fatal cases is the sum of direct medical and non-medical costs and indirect cost of an average cost of a hospitalized case plus the indirect cost of dengue premature death.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of estimated annual aggregate dengue treatment cost in Puerto Rico in $US million (2002–2010).

We also disaggregated dengue illness costs by type of cost and source of financing. For the aggregate cost, the cost of fatal cases was computed as the sum of the direct medical and non-medical costs and the indirect cost of an average cost of hospitalized cases plus the indirect cost of dengue premature death. We found that direct non-medical cost represented only a minuscule 2% share of total costs. Direct medical cost represented 48% of aggregate treatment cost, and indirect costs represented 50%. Examining the aggregate cost by sources of financing, we found that households fund the highest share (48%) followed by government (24%), insurers (22%), and employers (7%). Households in Puerto Rico bear most of the financial burden from dengue illness. Table 5 shows the total cost by sources of financing and type of costs to understand the contribution of households to each type of cost. Among the costs incurred by households, about 50% were because of hidden indirect costs, such as the cost of absenteeism from work and school and the premature death of a household member from dengue.

Table 5.

Aggregate average annual financing of projected dengue cases by type of cost and source of financing averaged per year (2002–2010; in thousands of 2010 US dollars)

| Source of financing | Direct medical costs | Direct non-medical costs | Indirect costs | All types of costs | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance | $8,391 | $0 | $0 | $8,391 | 22 |

| Households | $2,305 | $775 | $15,434 | $18,514 | 48 |

| Employers | $0 | $0 | $2,590 | $2,590 | 7 |

| Government | $7,798 | $0 | $1,450 | $9,248 | 24 |

| Total | $18,495 | $775 | $19,474 | $38,744 | 100 |

| Percent | 48 | 2 | 50 | 100 |

Table 6 presents the total cost of treated dengue cases corresponding to the range of expansion factors on ambulatory care. With the increase of the expansion factors from 5 to 27, the total treatment cost of dengue increased by 43% from $26.2 ($7.03 per capita) to $37.49 million ($1.06 per capita). With larger expansion factors, more financial burden shifted to households, because households have to pay higher relative costs for ambulatory care than for inpatient care. The contribution of households to the total treatment cost of dengue increases to 51.6% if we use an expansion factor of 27 for ambulatory care compared with 48.7% if we use an expansion factor of 5.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis on the aggregate average annual cost of dengue illness using a range of expansion factors for ambulatory care (in millions of US dollars) from 2002 to 2010

| Type of cost and source of financing | Possible expansion factor | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | |

| Breakdown by type of cost ($) | ||||||||||||

| Direct medical costs | 12.24 | 12.55 | 12.86 | 13.17 | 13.49 | 13.80 | 14.11 | 14.42 | 14.73 | 15.04 | 15.36 | 15.67 |

| Direct non-medical costs | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.73 |

| Indirect costs | 13.44 | 14.13 | 14.83 | 15.52 | 16.22 | 16.92 | 17.61 | 18.31 | 19.01 | 19.70 | 20.40 | 21.09 |

| Breakdown by source of financing ($) | ||||||||||||

| Insurance | 5.89 | 5.97 | 6.06 | 6.14 | 6.23 | 6.31 | 6.40 | 6.48 | 6.57 | 6.65 | 6.74 | 6.82 |

| Households | 12.75 | 13.35 | 13.96 | 14.56 | 15.16 | 15.76 | 16.36 | 16.96 | 17.56 | 18.16 | 18.76 | 19.36 |

| Employers | 1.38 | 1.52 | 1.65 | 1.79 | 1.93 | 2.06 | 2.20 | 2.33 | 2.47 | 2.61 | 2.74 | 2.88 |

| Government | 6.16 | 6.36 | 6.57 | 6.78 | 6.98 | 7.19 | 7.40 | 7.60 | 7.81 | 8.02 | 8.22 | 8.43 |

| Total | 26.18 | 27.21 | 28.24 | 29.26 | 30.29 | 31.32 | 32.35 | 33.38 | 34.41 | 35.44 | 36.47 | 37.49 |

The aggregate average annual economic cost of dengue illness in Puerto Rico is $38.7 million ($10.40 per capita). As shown in Table 7, combining the cost of dengue illness with costs associated with dengue surveillance and vector control activities, estimated recently for the years 2002 to 2007 in Puerto Rico and adjusted to 2010 price levels,27 increases the total economic cost of dengue illness to $46.4 million ($12.47 per capita). Analyzing the overall economic cost of dengue in Puerto Rico, including dengue surveillance and vector control activities, indicates that 36% of this cost is incurred by the government (both the state and municipalities), 40% is incurred by households, 18% is incurred by insurance, and 6% is incurred by employers.

Table 7.

The average annual aggregate economic cost of dengue in Puerto Rico for 2002–2010

| Aggregate amount (million) | Per capita amount | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illness costs | |||

| Total illness cost | $38.74 | $10.40 | 83.4 |

| Direct cost | $19.27 | $5.17 | 41.5 |

| Indirect cost | $19.47 | $5.23 | 41.9 |

| Vector control and surveillance* | |||

| Total prevention cost† | $7.70 | $2.07 | 16.6 |

| Vector control | $6.98 | $1.87 | 15.0 |

| Surveillance | $0.73 | $0.20 | 1.6 |

| Total | $46.45 | $12.47 | 100.0 |

Excludes the in-kind contribution of CDC dengue branch in Puerto Rico.

Prevention cost refers to dengue vector control and surveillance.

Discussion

The burden of dengue illness is high in Puerto Rico: the weighted average cost of treatment per case is $3,078, representing 19% of the per capita GDP ($16,300 in 2010).40 Of this burden, 48% is incurred by households, 24% is incurred by the government, 22% is incurred by insurance, and 7% is incurred by employers; 50% of this cost is because of productivity losses (indirect cost) that affect households and employers as well as the government. The number of days affected by dengue for both patients and household members averaged 30.5 days per case, of which 24.6% (7.2 days) are because of absenteeism from school and work. The aggregate time lost for all patients and household members was 136 person-years for laboratory-confirmed cases and 579 person-years lost after adjustment for underreporting.

The economic impact of dengue per case on work absenteeism in Puerto Rico (5.3 days) is higher than the corresponding numbers of workdays missed for the following other conditions: laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States (2.8–4.9 days),46 laboratory-confirmed influenza in other industrialized countries (1.5--4.9 days),47 1.6 days for working mothers and 0.6 days for working fathers of children with acute otitis media (AOM) in Israel, and 1.9 days for AOM in Finland.48,49

During the last decade, several studies have addressed the economic burden of dengue in various settings.12,50–61 Some of these studies were retrospective and relied on official records, some focused on hospitalized cases (treatment setting), and others reported cases and direct medical cost. Few conducted a comprehensive analysis of the economic impact of dengue using a prospective design and included direct non-medical cost as well as indirect costs to the overall cost of dengue.12,52,58,61 Moreover, these studies were facility-based and focused on limited geographic areas, population, or an epidemic year.

This paper is the first, to our knowledge, to use a systematic and comprehensive approach to estimate the economic impact of dengue for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico by combining multiple sources: patient interviews, medical records, and financial data from health facilities, insurance companies, and patients. The methodology used assists in addressing the variation in dengue cases observed in epidemic versus endemic years by taking the average number of cases reported between 2002 and 2010. To our knowledge, this paper is also the first to show how the economic cost of a dengue episode was distributed among different societal groups; households, employers, insurers, and the government.

Several limitations in the study must be acknowledged. First, the patient interviews took place, on average, 2 months after the onset of symptoms because of the multiple steps in analyzing the laboratory data, contacting the facility, contacting the patient, and arranging the interview. This unavoidable lag raised some concerns regarding recall bias. Nevertheless, our validation showed that self-reporting of hospital duration was reasonably accurate, with the ratios being close to the ideal value of 1.00. Second, our sample was limited to non-fatal cases; we used mortality data from the Pan American Health Organization to reach our estimates for fatal cases of 17.8% of aggregate illness cost and 14.9% of the overall economic cost of dengue.62 Third, because of data limitations, we were not able to estimate the impact of dengue on travelers or tourism. Dengue has been diagnosed in an increasing proportion of febrile travelers returning from infected areas, posing a risk for travelers who may both acquire and spread dengue virus.63–65 Research elsewhere has shown that the potential impacts on tourism could be substantial.66 Therefore, our estimates are conservative.

The share of dengue costs for illness in Puerto Rico (83%) is roughly comparable with the share from Panama (56%), the only other known comparable study.52 The per capita economic cost of dengue illness, surveillance, and vector control activities in Puerto Rico ($12.47) is double the cost in Panama ($5.22) in 2005. Although Panama's GDP per capita ($4,630)52 was much lower than the GDP for Puerto Rico ($16,300),40 the data from Panama come from an epidemic year when illness costs might be unusually high.52 The work by Suaya and others12 estimated the economic impact of dengue illness for officially reported dengue cases in five countries in the Americas. This cost was $135.2 million ($0.73 per capita) in Brazil, $10.2 million ($0.38 per capita) in Venezuela, $1.7 million ($0.28 per capita) in El Salvador, $1.2 million ($0.09 per capita) in Guatemala, and $0.9 million ($0.28 per capita) in Panama.12 The relatively higher economic cost of dengue for officially laboratory-confirmed dengue cases in Puerto Rico ($10.8 million [$2.89 per capita]) is consistent with the island's higher GDP per capita.

The aggregate overall economic cost of dengue, including disease surveillance and vector control, represents 0.06% of Puerto Rico's overall GDP for the year 2010 and based on GDP per capita, is equivalent to the aggregate annual economic output of 2,450 people. Because the cost of illness is five times the cost of surveillance and vector control, it is likely that increases in surveillance and vector control would pay off economically. For example, if a 10% increase in spending on vector control could reduce dengue incidence by 10%, it could reduce the cost of illness by 10% and save $5 on illness treatment for every $1 increase in surveillance and vector control spending. Of all publicly funded health spending in Puerto Rico, 62% is funded by the federal government.67 Sound investments related to dengue would benefit not only the residents of Puerto Rico but all taxpayers throughout the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to Jose A. Suaya, MD, PhD, for the initial questionnaire development; Rana Sughayyar, MS, for programming the questionnaire; Migda Dieppa, MS, for patient interviews; D. Fermin Aguello, MD, and Kay Tomashek, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Dengue Branch for ongoing support and assistance with surveillance data; Laurent Coudeville, PhD, and Camille Reygrobellet, PharmD, MSc, for helpful comments; and Clare L. Hurley, MMHS, for editorial assistance.

Appendix 1. Flowchart of interviewee sampling and enrollment process.

Footnotes

Financial support: This article is part of a study to estimate the economic burden of dengue in Puerto Rico funded by a contract from Sanofi Pasteur to Brandeis University.

Disclosure: This article is part of a study to estimate the economic burden of dengue in Puerto Rico funded by a contract from Sanofi Pasteur to Brandeis University. However, the sponsor was not involved in the implementation of the research or the preparation of the manuscript.

Authors' addresses: Yara A. Halasa, Donald S. Shepard, and Wu Zeng, Brandeis University, Schneider Institutes for Health Policy, The Heller School, Waltham, MA, E-mails: yara@brandeis.edu, shepard@brandeis.edu, and wuzengcn@brandeis.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Vector Borne Diseases Dengue: Entomology and Ecology. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/entomologyEcology/index.html Available at. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- 2.Farrar J, Focks D, Gubler D, Barrera R, Guzman MG, Simmons C, Kalayanarooj S, Lum L, McCall PJ, Lloyd L, Horstick O, Dayal-Drager R, Nathan MB, Kroeger A. Towards a global dengue research agenda. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzman A, Isturiz RE. Update on the global spread of dengue. Int J Antimicrob. 2010;36S:S40–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guha-Sapir D, Schimmer B. Dengue fever: new paradigm for changing epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2005;2:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehorn J, Farrar J. Dengue. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:161–173. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control—New Edition. Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank, WHO; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singhasivanon P, Jacobson J. Dengue is a major global health problem. Foreword. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(09)70285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubler DJ. Emerging vector-borne flavivirus diseases: are vaccines the solution? Vaccine. 2011;10:563–565. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman MG, Halstead SB, Artsob H, Buchy P, Farrar J, Gubler DJ, Hunsperger E, Kroeger A, Margolis HS, Martínez E, Nathan MB, Pelegrino JL, Simmons C, Yoksan S, Peeling RW. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:S7–S16. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beatty M, Beutels P, Meltzer MI, Shepard DS, Hombach J, Hutubessy R, Dessis D, Coudeville L, Dervaux B, Wichmann O, Margolis HS, Kuritsky JN. Health economics of dengue a systematic literature review and expert panel's assessment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:473–488. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyle JL, Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Siqueira JB, Martelli CT, Lum LCS, Tan LH, Kongsin S, Jiamton S, Garrido F, Montaya R, Armien B, Huy R, Castillo L, Sah BK, Sughayyar R, Tyo KR, Halsted SB. Cost of dengue cases in eight countries in Americas and Asia, a prospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:845–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Media Center Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever, Fact Sheet No. 117. 2009. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/index.html Available at. Accessed December 10, 2009.

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO) Report of the Scientific Working Group on Dengue. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemungkorn M, Thisyakorn U, Thisyakorn C. Dengue infection: a growing global health threat. Biosci Trends. 2007;1:90–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halstead SB. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science. 1988;239:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster DP, Farrar J, Rowland-Jones S. Progress towards a dengue vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:678–687. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isturiz RE, Gubler DJ, Castillo JB. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in Latin America and the Caribbean. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:121–140. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiura H. Duration of short-lived cross-protection immunity against a clinical attack of dengue: a preliminary estimate. Dengue Bull. 2008;32:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halstead SB. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2003;60:421–467. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)60011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kliks SC, Nisalak A, Brandt WE, Wahl L, Burke DS. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus growth in human monocytes as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:444–451. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schieffelin JS, Costin JM, Nicholson CO, Orgeron NM, Fontaine KA, Isern S, Michael SF, Robinson JE. Neutralizing and non-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against dengue virus E protein derived from a naturally infected patient. Virol J. 2010;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilder-Smith A, Ooi EE, Vasudevan SG, Gubler DJ. Update on dengue: epidemiology, virus evolution, antiviral drugs, and vaccine development. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morens DM, Fauci AS. Dengue and hemorrhagic fever: a potential threat to public health in the United States. JAMA. 2008;299:214–216. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.31-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Departamento de Salud Gobierno de Puerto Rico, CDC Dengue Branch Informe Semanal de Vigilancia de Dengue. 2011. http://www.salud.gov.pr/Datos/VDengue/DengueInfo/Pages/DatosEstadisticos.aspx Available at. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control Dengue Branch, Puerto Rico Department of Health Dengue Update. 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/Dengue/dengue_upd/index.html Available at. Accessed May 11, 2011.

- 27.Perez-Guerra C, Halasa Y, Rivera R, Peña M, Ramírez V, Cano MP, Shepard DS. Economic cost of dengue public prevention activities in Puerto Rico. Dengue Bull. 2010;34:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigau-Perez JG, Clark GG. How to respond to a dengue epidemic: overview and experience in Puerto Rico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17:282–293. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winch P, Leontsini E, Rigau-Perez JG, Ruiz-Perez M, Clark GG, Gubler DJ. Community-based dengue prevention programs in Puerto Rico: impact on knowledge, behavior, and residential mosquito infestation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:363–370. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomashek KM, Rivera A, Munoz-Jordan JL, Hunsperger E, Santiago L, Padro O, Garcia E, Sun W. Description of a large island-wide outbreak of dengue in Puerto Rico, 2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Allmen SD, Lopez-Correa RH, Woodall JP, Morens DM, Chiriboga J, Casta-Velez A. Epidemic dengue fever in Puerto Rico, 1977: a cost analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:1040–1044. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez E. Dengue Outbreak in Puerto Rico (1994–95): Hospitalization Cost Analysis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Division of Vector Borne and Infectious Diseases Dengue in Puerto Rico. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/about/inPuerto.html Available at. Accessed January 9, 2011.

- 34.World Health Organization (WHO) Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi AS, Finnegan B, Shin P, Jones E, Rosenbaum S. Examining the Experiences of Puerto Rico's Community Health Centers under the Government Health Insurance Plan, Policy Research Brief No. 8. Washington, DC: George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Census Bureau School Enrollment 2000. Table 1. Population Aged 3 and Over by Enrollment Status and Level for the United States, Regions, States, and for Puerto Rico: 1990 and 2000. 2003. http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-26.pdf Available at. Accessed January 19, 2011.

- 37.Central Intelligence Agency Federal and State Minimum Wage Rates, Laws, and Resources. 2008. http://www.minimum-wage.org/states.asp?state=Puerto%20Rico Available at. Accessed January 20, 2011.

- 38.Dechant EJ, Rigau-Perez JG, Puerto Rico Association of Epidemiologists Hospitalizations for suspected dengue in Puerto Rico, 1991–1995: estimation by capture-recatpure methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:574–578. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meltzer MI, Rigau-Perez JG, Clark GG, Reiter P, Gubler DJ. Using disability-adjusted life years to assess the economic impact of dengue in Puerto Rico: 1984–1994. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:265–271. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramos MM, Argüello DF, Luxemburger C, Quiñones L, Muñoz JL, Beatty M, Lang J, Tomashek KM. Epidemiological and clinical observations on patients with dengue in Puerto Rico: results from the first year of enhanced surveillance—June 2005–May 2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Guerra C, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, Vargas-Torres D, Clark G. Community beliefs and practices about dengue in Puerto Rico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;25:218–226. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivera A, Tomashek KM, Munoz J, Hunsperger E, Blau D, Sharp T, Torres J, Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch Gonzalez L, Deseda C, Rivera I, Sanabria D, Torres J, Rodriguez R, Serrano J, Davila F, Lopez D, Margolis H. Enhanced Surveillance for Fatal Dengue in Puerto Rico. Philadelphia, PA: 2011. Presented at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 60th Annual Meeting. December 4–8, Abstract 1335. [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Social Security Administration Actuarial Publications, Period Life Table. 2007. http://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html Available at. Accessed November 1, 2011.

- 44.Neff JM, Morris L, Gonzalez-Alcover R, Coleman PH, Lyss SB, Negron H. Dengue fever in a Puerto Rican community. Am J Epidemiol. 1967;86:162–184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welcome to Puerto Rico Economy. 2006. http://www.topuertorico.org/economy.shtml Available at. Accessed October 21, 2010.

- 46.Akazawa M, Sindelar JL, Paltiel AD. Economic costs of influenza-related work absenteeism. Value Health. 2003;6:107–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keech M, Beardsworth P. The impact of influenza on working days lost: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:911–924. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niemela M, Uhari M, Mottonen M, Pokka T. Costs arising from otitis media. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:553–556. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenberg D, Bilenko N, Liss Z, Shagan T, Zamir O, Dagan R. The burden of acute otitis media on the patient and the family. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:576–581. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson KB, Chunsuttiwat S, Nisalak A, Mammen MP, Jr, Libraty DH, Rothman AL, Green S, Vaughn DW, Ennis FA, Endy TP. Burden of symptomatic dengue infection in children at primary school in Thailand: a prospective study. Lancet. 2007;369:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Añez G, Balza R, Valero N, Larreal Y. Impacto económico del dengue y del dengue hemorrágico en el Estado de Zulia, Venezuela, 1997–2003. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19:314–320. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892006000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armien B, Suaya JA, Quiroz E, Sah BK, Bayard V, Marchena L, Campos C, Shepard DS. Clinical characteristics and national economic cost of the 2005 dengue epidemic in Panama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:364–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canyon DV. Historical analysis of the economic cost of dengue in Australia. J Vector Dis. 2008;45:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chandralekha GP, Trikha A. The north Indian dengue outbreak 2006: a retrospective analysis of intensive care unit admissions in a tertiary care hospital. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark DV, Mammen MP, Jr, Nisalak A, Puthimethee V, Endy TP. Economic impact of dengue fever/dengue hemorrhagic fever in Thailand at the family and population levels. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:786–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coudeville L, Shepard DS, Zambrano B, Dayan G. Dengue Economic Burden in the Americas: Estimates from Dengue Illness. Washington, DC: 2009. Presented at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 58th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, November 18–22, poster 442. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garg P, Nagpal J, Kairnar P, Sinveratne SL. Economic burden of dengue infections in India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huy R, Wichmann O, Beatty M, Ngan C, Duong S, Margolis HS, Vong S. Cost of dengue and other febrile illnesses to households in rural Cambodia: a prospective community-based case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torres JR, Castro J. The health and economic impact of dengue in Latin America 1. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23((Suppl 1)):S23–S31. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007001300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valdés LG, Mizhrahi JV, Guzmáán MG. Impacto económico de la epidemia de dengue 2 en Santiago de Cuba, 1997. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 2002;54:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kongsin S, Jaimton S, Suaya J, Vasanawathana S, Sirisuvan P, Shepard DS. Cost of dengue in Thailand. Dengue Bull. 2010;34:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Fact Sheet: Dengue. http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=264&Itemid=363&lang=en Available at. Accessed November 1, 2011.

- 63.Allwinn R, Hofknecht N, Doerr HW. 12 Denue in travelers is still underestimated. Intervirology. 2008;12:695–699. doi: 10.1159/000131667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.LaRouche G, Renaudat C, Tarantola A, Caro V, Ledrans M, Dejour-Salamanca D, Diancourt L, Tolou H, Grandadam M, Gastellu-Etchegorry M. Increase in dengue fever imported from Cote d'Ivoire and West Africa to France. Dengue Bull. 2010;34:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization (WHO) Weekly Epidemiological Monitor. Cairo, Egypt: Regional Office of the Eastern Mediterranean; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mavalankar D, Puwar T, Murtola T, Vasan S, Field R, Alphey N, Gong H-F, Shepard DS. Quantifying the Impact of Chikungunya and Dengue on Tourism Revenues. W.P.No. 2009-02-03. Ahmedabad, India: Indian Institute of Management Working Paper Series; 2009. http://www.iimahd.ernet.in/publications/data/2009-02-03Mavalankar.pdf Accessed July 30, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Health Systems Profile Puerto Rico: Monitoring and Analysis Health Systems Change/Reform. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization and USAID; 2007. [Google Scholar]