Abstract

The main causative agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in Suriname is Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis. This case report presents a patient infected with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis, a species never reported before in Suriname. This finding has clinical implications, because L. braziliensis has a distinct clinical phenotype characterized by mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, a more extensive and destructive form of CL that requires different treatment. Clinicians should be aware that chronic cutaneous ulcers in patients from the Guyana region could be caused by L. braziliensis.

Introduction

The parasitic disease cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an increasing health threat in Suriname and is caused by single-cell parasites of the genus Leishmania. In Suriname, Leishmania parasites cause a chronic infection with a spectrum of skin ulcers as the main clinical presentation. In Suriname, CL is known as boschyaws or boessie-yassi,1 and the parasite Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis is the most common cause of the disease2; the diversity of clinical CL forms suggests that other Leishmania species may be present in Suriname. Indeed, recent reports from Suriname confirm infection with Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni, Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis, and Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi.3,4 Variation in treatment outcome alongside parasite species diversity indicates that the standard therapy (pentamidine intramuscular [IM]) may not always be suitable. Therefore, identification of parasite species is important. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) are the standard techniques for species identification and have a high sensitivity and specificity.5,6

This report describes a patient who presented with ulcerative lesions after a hunting trip to West Suriname. With NAAT analysis, the patient proved to be infected with Leishmania braziliensis, a species of Leishmania not reported in Suriname until now.

Patient, Materials, And Methods

Case report.

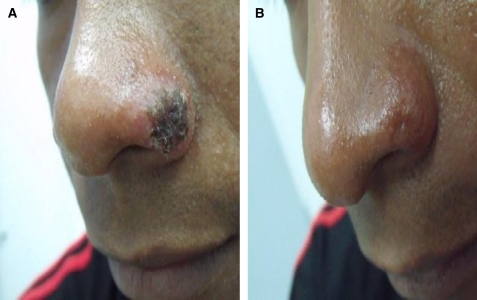

A 26-year-old male presented at the outpatient clinic of the Dermatology Service in Paramaribo (Suriname) in January 2010 with three nodular lesions with central ulceration, two (20 and 27 mm in diameter, respectively) on the right lower arm and one (12 mm in diameter) on the nostril (Figure 1A). He noticed the skin lesions 2 weeks after returning from a visit to the hinterlands in West Suriname in December 2009. Although he travels often to this area for fishing and hunting, this is the first time he acquired these types of lesions. The lesions increased in size over the period of 1 month and the patient developed lymphadenopathy on the right lower arm. During the first visit, no apparent mucosal lesions were noticed.

Figure 1.

Ulcerative lesion with hemorrhagic crust caused by Leishmania braziliensis on the nostril of the patient, January–April 2010, Dermatologic Service, Paramaribo Suriname. (A) Before treatment and (B) 12 weeks after treatment with two doses of 7 mg/kg body weight pentamidine isethionate intramuscular (IM).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis was suspected and lesional biopsy material was obtained. A Giemsa stain of biopsy smear, histopathology, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were all positive for Leishmania parasites. After written informed consent was obtained, the patient was entered into the PELESU study (Clinical, Parasitological, and Pharmaco-Economical evaluation of 3 days versus 7 days pentamidine isethionate regimen for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Suriname, Trial ID: NTR 2076). The patient received two IM injections of pentamidine each of 7 mg per kg body weight, with an interval of 2 days. After treatment the patient was followed up 6 and 12 weeks later to evaluate the healing process.

Clinical samples.

The lesion and the adjacent skin were cleaned and sterilized with disinfectant. Using a sterile disposable skin biopsy puncher, three skin biopsy samples of 2 mm in diameter were taken aseptically from the edge of the lesion according to the recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO).7 One biopsy was taken before treatment, one 6 weeks after treatment, and one 12 weeks after treatment, all from the same lesion. The biopsies were placed in 1 mL L6 lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris HCl (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, CT), 5 M guSCN (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), 20 mM EDTA (Tritriplex, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and 0.1% Triton-X-100 (Packard, Downers Grove, IL), and stored at −20°C.

Leishmania DNA extractions were performed according to the protocol described by Boom and others.8 Briefly, the skin biopsy samples were disrupted by shaking with a 5-mm stainless steel bead in a mini-beadbeater-16 model 607 (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for 5 min. Next, the ahomogenates were collected and mixed for 5 min with 30 μL silica gel (SiO2, Sigma S5631; St. Louis, MO) to trap the DNA, and centrifuged for 15 sec at 12,000×g. The silica pellet was collected, and washed repeatedly with L2 wash buffer (50 mM Tris HCl (Boehringer), 5 M guSCN (Fluka), 70% ethanol and acetone. The DNA was eluted in 100 μL TE buffer (Tris EDTA buffer, 100× concentrated Sigma) and stored at −20°C until analysis.

To identify the infecting Leishmania species, a PCR- restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) assay was performed on the spliced leader RNA gene PCR-RFLP (mini-exon) as described by Marfurt and others.9 Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis MHOM/BR/75/M4147 and L. (Viannia) brasiliensis MHOM/BR/79/M2903 were included in the PCR run as reference DNA. After amplification, the PCR amplicons were digested using the restriction enzyme HaeIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 2 h at 37°C. The resultant restriction digestions were analyzed on a 3% agarose gel and fragments were visualized by UV light.

To confirm that the patient was infected with L. braziliensis, sequencing of the mini-exon was performed using primers Fme2 and Rme2 (5′-ACT TTA TTG GTA TGC GAA ACT TCC GG-3′ and 5′ACA GAA ACT GAT ACT TAT ATA GCG TTA G-3′). Products were sequenced using primer Rme2 (Macrogen Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The obtained nucleotide sequence was submitted to GenBank database under accession no. HE610677.

Results And Discussion

The PCR-RFLP and sequencing revealed that this patient was infected with L. braziliensis, a species previously not observed in Suriname. After pentamidine treatment, all lesions healed within 6 weeks without adverse events. At Week 12, all lesions had healed with atrophic scars and no relapse had occurred (Figure 1B). The patient did not return with relapse symptoms and could not be traced after completion of the study.

Leishmania braziliensis infection is often diagnosed in countries in South and Central America10,11; however, this is the first confirmed case in Suriname. In neighboring French Guyana L. guyanensis is the main cause of CL, although cases caused by L. braziliensis are occasionally encountered.12 Until recently it was believed that L. guyanensis was the only species prevailing in Suriname.13 Because of the increasing travel between Suriname and neighboring countries, like Brazil and French Guyana, it is possible that other Leishmania species, such as L. braziliensis, have been imported.

The current treatment of CL in Suriname with pentamidine isethionate dates back to 1994 and has since then been used successfully.2 Pentamidine isethionate (4 mg/kg body weight) intramuscularly is given three times with a 2- to 3-day interval. Recent observations of treatment failures and relapses after the pentamidine standard therapy (Lai A Fat RF, personal communication) indicates the emergence of reduced parasite susceptibility, or the possible introduction in Suriname of pentamidine-resistant species, other than L. guyanensis.

Here, the patient was successfully treated with pentamidine; however, this is not the preferred treatment of CL caused by L. braziliensis in Brazil and other Latin American countries. Pentavalent antimonials and recently oral miltefosine show fewer treatment failures and/or relapses.14,15 For local treatment of L. braziliensis WHO recommends: 1) 15% paromomycin and 12% methylbenzethonium chloride ointment twice daily for 20 days, 2) thermotherapy: 1–3 sessions with localized heat (50°C for 30 s), 3) intralesional antimonials: 1–5 mL per session every 3–7 days (1–5 infiltrations).16 Recommended systemic treatment of L. braziliensis according to the WHO includes: 1) pentavalent antimonials; 20 mg Sb5+/kg per day IM or intravenous for 20 days, 2) amphotericin B deoxycholate: 0.7 mg/kg per day, by infusion, for 25–30 doses, 3) liposomal amphotericin B: 2–3 mg/kg per day, by infusion, up to 20–40 mg/kg total dose.16

Although this patient showed no signs of mucosal involvement, it has been reported that 3–5% of patients with L. braziliensis develop mucocutaneous lesions (MCL) in Brazil.11,17 In Suriname MCL caused by L. guyanensis is very rare. Since we reported the occurrence of L. braziliensis in Suriname, clinicians need to be aware of possible mucocutaneous involvement in patients who contracted CL in Suriname.

In conclusion, L. braziliensis is present in Suriname. Here, a patient presented with ulcerations on the arms and nose, but no mucous lesions were observed. Treatment with pentamidine, the standard treatment of CL in Suriname, healed all lesions. Clinicians need to be aware of MCL caused by L. braziliensis in CL patients from Suriname. Further investigation and species identification is needed, especially for the patients who show treatment failure to the standard pentamidine regimen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Aldert Bart (Parasitology group, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam) and Gerard Schoone (KIT Biomedical Research, Amsterdam) for their advice with sequencing the mini-exon gene.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study received financial support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research/Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research–Science for Global Development (project W016531300; Integrated Programme “Leishmaniasis in Suriname”).

Authors' addresses: Ricardo V. P. F. Hu and Leslie O. A. Sabajo, Dermatology Service, Ministry of Health, Paramaribo, Suriname, E-mails: ricahu@gmail.com and lesdolores13@hotmail.com. Alida D. Kent and Dennis R. A. Mans, Department of Parasitology, Anton de Kom University of Suriname, Paramaribo, Suriname, E-mails: alida24@yahoo.com and d.mans@uvs.edu. Emily R. Adams, Charlotte van der Veer, and Henk D. F. H. Schallig, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen (KIT)/Royal Tropical Institute, KIT Biomedical Research, Parasitology Unit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, E-mails: e.adams@kit.nl, c.vd.veer@kit.nl, and h.schallig@kit.nl. Henry J. C. de Vries, Department of Dermatology, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and STI outpatient clinic, Cluster Infectious Diseases, Municipal Health Service Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, E-mail: h.j.devries@amc.uva.nl. Rudy F. M. Lai A. Fat, Department of Dermatology, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, E-mail: rlaiafat@sr.net.

References

- 1.Flu PC. Die aetiologie der in Surinam vorkommenden sogenannten “Boschyaws,” einer der Aleppobeule analogen Erkrankung. Centralbl Bakt parasit Kde Orig. 1911;60:624–637. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai A Fat EJ, Vrede MA, Soetosenojo RM, Lai A Fat RF. Pentamidine, the drug of choice for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Surinam. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:796–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Meide WF, de Vries H, Pratlong F, van der Wal A, Sabajo L. Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis infection in Suriname. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:857–859. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.070433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Thiel PP, Gool T, Kager PA, Bart A. First cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi infection in Surinam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:588–590. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Meide WF, Schoone GJ, Faber WR, Zeegelaar JE, de Vries HJ, Schallig HD, Ozbel Y, Lai A Fat RF, Coelho LJ, Kassi M, Schallig HD. Quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based assay as a new molecular tool for the detection and qualification of Leishmania parasites in skin biopsies. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5560–5566. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5560-5566.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schonian G, Nasereddin A, Dinse N, Schweynoch C, Schallig HDFH, Presber W, Jaffe CL. PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Control of the leishmaniasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;48:793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boom R, Sol C, Salimans M, Jansen C, Wertheim van Dillen P, van der Noordaa L. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marfurt J, Niederwieser I, Makia N, Beck H, Felger I. Diagnostic genotyping of Old and New World Leishmania species by PCR-RFLP. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimaldi G, Jr, Mahan-Pratt D. Leishmaniasis and its etiologic agents in the New World: an overview. Prog Clin Parasitol. 1991;2:73–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones TC, Johnson WD, Jr, Bareto AC, Lago E, Badaro R, Cerf B, Reed SG, Netto EM, Tada MS, Franca TF. Epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis braziliensis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:73–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotureau B. Ecology of the Leishmania species in the Guianan ecoregion complex. Am J Trop Med. 2006;74:81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Meide WF, Jensema AJ, Akrum RA, Sabajo LO, Lai A Fat RF, Lambregts L, Schallig HD, van der Paardt M, Faber WR. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Suriname: a study performed in 2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado PR, Ampeuro J, Guimaraes LH, Villasboas L, Rocha AT, Schriefer A, Sousa RS, Talhari A, Penna G, Carvalho EM. Miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis in Brazil: a randomized and controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen EM, Cruz-Saldarriaga M, Llanos-Cuentas A, Luz-Cjuno M, Echevarria J, Miranda-Verastegui C, Colina O, Berman JD. Comparison of meglumine antimoniate and pentamidine for Peruvian cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Control of the leishmaniasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2010;949:62–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lessa MM, Lessa HA, Castro TW, Oliveira A, Scherifer A, Machado P, Carvalho EM. Mucosal leishmaniasis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73:843–847. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]