Abstract

Islet transplantation is an experimental therapy for selected patients with type 1-diabetes (T1DM). It remains limited by immunosuppressive drug toxicity, progressive loss of insulin independence, allosensitization, and the need for multiple islet donors. We describe our experience with an efalizumab-based immunosuppressive regimen as compared to the prevailing standard regimen, the Edmonton protocol. Twelve patients with T1DM received islet transplants: 8 were treated with the Edmonton protocol; 4 were treated with daclizumab induction, a 6-month course of tacrolimus, and maintenance with efalizumab and mycophenolate mofetil. The primary endpoint was insulin independence after one islet infusion. Only 2 Edmonton protocol treated patients achieved the primary endpoint; 6 required islets from multiple donors, and all experienced leukopenia, mouth ulcers, anemia, diarrhea, and hypertransaminasemia. Four became allosensitized. All patients treated with the efalizumab-based regimen achieved insulin independence with normal hemoglobin A1c after a single islet cell infusion and remained insulin independent while on efalizumab. These patients experienced significantly fewer side effects and none became allosensitized. Trial continuation was terminated by withdrawal of efalizumab from the market. These data suggest that this efalizumab-based regimen prevents islet rejection, is well tolerated, and allows for single donor islet transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) afflicts over 1 million people in the United States (1). Intensive insulin therapy can forestall the development and progression of long-term complications of T1DM (2) but is burdensome to the patient and incompletely effective. Tight glucose control requires frequent blood glucose monitoring with multiple insulin injections or use of an insulin pump, and it is estimated that in practice less than half of patients striving for intensive insulin therapy actually sustain a HbA1c below 7.5% (3). Those maintaining intensive therapy face a 10% annual risk of severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention.

Given the limitations of exogenous insulin management there has been a sustained interest in strategies for β-cell replacement to achieve more physiologic and less cumbersome means of glucose control. In particular, islet transplantation (ITx) has continued to be a conceptually appealing approach, and in the last decade has been shown to achieve insulin-independence in selected patients with T1DM. The most successful approach has been termed the “Edmonton protocol” based upon the pioneering experience reported from the University of Alberta in 2000 (4). This method of islet production and delivery uses an immunosuppressive regimen consisting of daclizumab, tacrolimus and sirolimus and has proven successful for up to 1 year in approximately 60% of selected patients (5). Although a major advance, it has become clear that this regimen remains imperfect. Specifically, significant toxicities accompany the chronic administration of tacrolimus and sirolimus, the vast majority (90%) of patients lose insulin independence within five years, and most patients develop donor-HLA-specific alloantibodies. This later limitation impedes subsequent access to more conventional forms of transplantation, and is significantly exacerbated by the frequent requirement for multiple islet donors to achieve insulin-independence under the Edmonton approach.

In an effort to address these issues we evaluated an immunosuppressive regimen based on the use of efalizumab, a CD11a-specific humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the Leukocyte Function Antigen (LFA-1) pathway. LFA-1 is comprised of two subunits, CD11a and CD18, and binds Intercellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM)-1 (6). Efalizumab impedes LFA-1 to ICAM-1 binding and in doing so prevents lymphocyte diapedesis and disrupts adhesion events necessary for optimal T cell function. Preclinical murine and primate studies have demonstrated that LFA-1-specific antibodies prolong the survival of islet and other organ allografts (7–10) and phase I/II studies in renal transplantation have suggested that efalizumab has efficacy in preventing human allograft rejection. Phase III studies have indicated that efalizumab is safe, effective, and well tolerated for up to 3 years of treatment in patients with psoriasis (11) and until recently efalizumab has been approved for the treatment of psoriasis.

We thus initiated clinical studies with efalizumab using a regimen specifically designed to avoid the chronic toxicities of 3 prevalent immunosuppressive agents – glucocorticosteroids, sirolimus, and calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs). We sought to avoid the diabetagenic properties of CNIs and steroids to promote sustained insulin independence with single donor islet transplants, and to reduce CNI- and sirolimus-related toxicities, particularly those related to the indefinite maintenance use of these drugs inherent in the Edmonton protocol. Herein we report the results of our experience with efalizumab-based islet transplantation compared to our results using the Edmonton protocol. The results of this pilot study indicate that an efalizumab-based regimen facilitates insulin-independence after single donor islet transplantation and is associated with limited morbidity.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Patients

All patients were enrolled in a protocol approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and underwent extensive screening and informed consent. Patients for both groups were highly selected with the 12 enrolled patients being derived from 943 screened patients. Inclusion was limited to adult patients with the onset of T1DM prior to age 40, who were insulin-dependent for more than 5 years, had evidence of hypoglycemic unawareness despite intensive endocrinologist assisted insulin management, and a body mass index (BMI) less than 26. All patients were required to have preserved renal function (measured 24 hour creatinine clearance >70 ml/min/1.73 m2 for females and >80 ml/min/1.73 m2 for males, and urinary protein excretion rate < 300 mg/24h). Patients with evidence of insulin resistance (insulin requirements >0.8 units/kg/day) were excluded, as were patients with significant co-morbid conditions to include malignancy, hyperlipidemia, coagulopathy, pregnancy, substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, severe cardiac disease, active infection, anemia, or any other condition that suggested that it was unsafe to undergo an islet cell transplant. Patients were enrolled sequentially with Group 1 patients enrolled prior to Group 2. Table 1 shows the relevant characteristics of all patients.

Table 1.

Recipient characteristics

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Age (years) | 42.3 | 46.5 | 28.9 | 52.2 | 51.3 | 45 | 51.4 | 50.2 | 44.4 | 60.8 | 30.5 | 45 |

| Gender | F | M | F | M | F | F | F | F | M | F | M | M |

| Body Weight (kg) | 56.8 | 78.2 | 61.0 | 68.3 | 70.5 | 55.8 | 57.6 | 35.0 | 67.3 | 63.2 | 76.0 | 80.0 |

| Body Mass Index | 22.9 | 22.5 | 23.2 | 23.0 | 23.9 | 22.5 | 18.0 | 15.8 | 20.7 | 23.9 | 24.9 | 22.6 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 33.5 | 30 | 24 | 35 | 41 | 16 | 31 | 23 | 35.5 | 40 | 16 | 23.0 |

| WBC (10E3/mcL) | 4.0 | 4.6 | 9.5 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 5.8 |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 15.0 | 12.1 | 14.3 | 12.3 | 12.8 | 15.5 | 12.3 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 10.7 | 13.8 | 14.3 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) | 25 | 17 | 19 | 23 | 30 | 15 | 18 | 12 | 17 | 23 | 16 | 21 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) | 29 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 21 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 24 | 24 | 22 |

| Daily insulin (Units/kg) | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.53 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 8.3 |

| Class I / II PRA | 11/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

Efficacy Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the proportion of insulin-independent subjects at day 75 (± 5 days) following the first islet cell infusion. Subjects were considered insulin-independent if they were able to titrate off insulin therapy for at least 1 week and all of the following criteria were met: HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, highest fasting capillary glucose <140 mg/dL, 90 minute post-prandial capillary glucose <180 mg/dl, fasting plasma glucose level ≤ 126 mg/dL with evidence of endogenous insulin production defined as fasting or stimulated C-peptide levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL.

Secondary endpoints included the proportion of subjects achieving insulin independence and a normal HbA1c at one year after a single islet infusion, the proportion of patients attaining and maintaining insulin independence and a normal HbA1c at one year after their completion transplant, the proportion of study participants exhibiting HbA1c values less than 6.5% at months 6, 12, 24 and 36 after the completion islet transplant and the proportion of study participants exhibiting a successful response to a standard mixed meal test at 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after the completion islet transplant.

Outcomes

Islet transplant failure was defined as loss of C-peptide as evidenced by stimulation tests showing C-peptide levels below the level of detectability of the assay, with resumption of insulin use. Safety was recorded, including incidence of post-transplant infections, malignancies, procedural complications, morbidity, and other adverse events (e.g., increased body weight and hypertension) associated with conventional immunosuppression. Renal function was measured by serum creatinine, and other relevant laboratory parameters including triglycerides, and total and fractionated cholesterol was assessed over time.

Islet Preparation and infusion

Pancreata were obtained from brain-dead multi-organ donors ranging in age from 19–58 years. Standard criteria for donor exclusion were applied to minimize the risk of donor-derived infection or cancer. Pancreata were procured using standard surgical techniques developed and employed for the procurement of human pancreata for transplantation as whole organs.

Islet isolation was performed as previously described (5, 12–14) Pancreata were perfused with Liberase (Roche Pharmaceuticals) for all subjects in Group 1 and subject 1 in Group 2. In April 2007, it was determined that the liberase manufacturing process utilized bovine brain derived raw material causing concern for the potential transmission of prions resulting in spongiform encephalopathies. Subsequently, SERVA collagenase (SERVA electrophoresis) and neutral protease were used for pancreas perfusions. Islet number, purity, and viability were assessed similarly in both groups and included assessment of the in vitro glucose-stimulated insulin secretory response stimulation index. The islet preparation was infused intraportally via a mini-laparotomy over a period of 15 to 60 minutes with heparin at a dose of 70 U/kg of recipient body weight with portal vein pressure measured throughout the infusion. The details of the donors and isolations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Donor characteristics

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Transplant | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Donor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age, years | 40 | 55 | 44 | 47 | 58 | 26 | 37 | 36 | 19 | 48 | 25 | 46 | 40 | 49 | 47 | 48 | 36 | 29 | 30 | |||||||||||

| Sex, F or M | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | M | M | F | M | |||||||||||

| Body weight, Kg | 91.6 | 80.5 | 92 | 84 | 91.7 | 95 | 102.3 | 93.6 | 89 | 98.3 | 86.3 | 76.8 | 71.3 | 90 | 79.8 | 102 | 97.3 | 127 | 130 | |||||||||||

| BMI | 28 | 24.5 | 33 | 32.5 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 34.5 | 26.5 | 29.24 | 26.5 | 25 | 22.5 | 28.7 | 28.3 | 12.4 | 34.6 | 43.9 | 36.8 | |||||||||||

| Cause of death | Head Trauma |

CVA | Anoxia | Head Trauma |

CVA | Head Trauma |

Head Trauma |

CVA | Head Trauma |

Head Trauma |

Head Trauma |

CVA | Head Trauma |

Head Trauma |

CVA | CVA | Anoxia | Head Trauma |

Head Trauma |

|||||||||||

| Blood Glucose | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Admission | 297 | 163 | 294 | 161 | 154 | 131 | 173 | 434 | 203 | 234 | 168 | 106 | 180 | 103 | 298 | 128 | 141 | 174 | 219 | |||||||||||

| Peak | 297 | 380 | 294 | 379 | 224 | 260 | 224 | 434 | 315 | 234 | 389 | 198 | 208 | 182 | 298 | 324 | 131 | 215 | 219 | |||||||||||

| Graft | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cold Ischemia time(hr) |

6:14 | 1:35 | 5:16 | 7:17 | 4:22 | 2:23 | 7:44 | 4:27 | 4:40 | 9:33 | 7:05 | 5:37 | 7:12 | 7:55 | 6:16 | 6:19 | 6:35 | 4:08 | 5:29 | |||||||||||

| Tissue volume, mL |

3.5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1.2 | 3 | 2.5 | 1.7 | |||||||||||

| Total islet equivalent |

696,883 | 313,325 | 350,260 | 749,888 | 250,681 | 631,090 | 528,545 | 536,735 | 383,100 | 447,019 | 373,280 | 664,169 | 387,630 | 603,522 | 656,863 | 541,139 | 625,747 | 669,949 | 457,793 | |||||||||||

| Islet Equivalent/kg |

12,269 | 4,007 | 5,128 | 10,244 | 4,110 | 10,788 | 7,739 | 8,220 | 5,434 | 7,245 | 6,690 | 12,299 | 6,730 | 9,766 | 18,768 | 8,041 | 9,901 | 8,815 | 5,722 | |||||||||||

| Islet Purity, % | 83 | 76 | 78 | 89 | 79 | 80 | 75 | 81 | 70 | 50 | 78 | 70 | 68 | 79 | 80 | 95 | 70 | 77 | 80 | |||||||||||

| Islet Viability,% | 94 | 86 | 97 | 100 | 96 | 93 | 86 | 92 | 98 | 100 | 92 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 94 | - | 88 | 87 | 91 | |||||||||||

| Stimulation Index |

1.4 | 1.84 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.96 | 2.2 | 2.05 | 1.79 | - | 1.04 | 2.3 | |||||||||||

| Endotoxin, EU/dg |

0 | <0.08 | 3.89 | 9.75 | 8.1 | 5.3 | 4.69 | 10.96 | 6.06 | <47 | 7.29 | 0.73 | 12.22 | 6.11 | 5 | <23.0 | <23.0 | <2.3 | <9.72 | |||||||||||

Treatment Protocols

Two separate trials were performed sequentially as open label, single-center feasibility studies. In both protocols up to 3 islet infusions were permitted per subject until insulin independence was reached. Immunosuppression was administered for each protocol as follows:

Edmonton Protocol (Group 1)

Daclizumab (Zenapax®, Roche Laboratories Inc.; 1 mg/kg) was administered intravenously at transplantation and every 14-days post transplant, for 5 total doses. Subjects who underwent multiple islet transplants received an additional course of daclizumab if the subsequent transplant procedure occurred more than two months after the first procedure. Sirolimus (Rapamune®, Wyeth Laboratories; 0.2mg/kg) was administered orally immediately prior to transplantation, and daily post-procedure at 0.1 mg/kg once daily, with the dose adjusted to achieve 24-hour whole blood trough levels of 12–15 ng/mL. Tacrolimus (Prograf®, Astellas; 1 mg) was administered orally immediately prior to transplantation, and continued postoperatively with the dose adjusted to achieve 12-hour whole blood trough levels of 3–5 ng/mL.

Efalizumab-Based Protocol (Group 2)

Daclizumab was administered as in Group 1. Efalizumab (Raptiva®, Genentech, Inc.; 1mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously immediately prior to the transplant procedure and weekly thereafter at 1mg/kg, with dose adjustments based on tolerability. Mycophenolate Mofetil (CellCept, Roche, Inc.; 1000mg) was administered orally immediately prior to transplant and continued at 1000mg twice daily thereafter with dose adjustments made based on tolerability. Tacrolimus, 1 mg, was administered immediately prior to transplantation and was continued at a dose of 1.0 mg twice daily, with the dose adjusted to achieve 12-hour whole blood trough levels of 8–10ng/ml for 1 month, 5–8ng/ml for the next 2 months, and 3–5ng/ml until month 6. Tacrolimus discontinued in Subjects 2–4 at month 6 and in subject 1 at month 12.

Monitoring

Flow cytometric crossmatches was performed for all subjects as previously described (15). HLA typing was performed by sequence specific priming (16) using commercial SSP kits (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA; Pel Freez, Brown Deer, WI). Antibody detection was performed using FlowPRA® screening, specificity and single antigen bead assays (One Lambda, Inc.,) (17). Antibody titres were measured in all study subjects with confirmed DSA. Glucose tolerance was determined by serial measurement of fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, and mixed meal glucose tolerance test (MMT) according to the metrics developed by the NIH Clinical Islet Transplant Consortium.

Statistical methods

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were compared using Student’s t-test with significance defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Recipient, Donor, and Transplant Characteristics

Transplants were performed between March 30, 2003 and October 15, 2008. Eight recipients in Group 1 were initially treated with the Edmonton protocol (daclizumab, tacrolimus and sirolimus) and the four recipients in Group 2 initially received the efalizumab-based regimen. The groups were similar with respect to age, BMI, duration of diabetes, and pre-transplant insulin requirement (Table 1). Donor and graft characteristics were also similar although donor weight and BMI trended higher in group 2 (Table 2). Islets from 15 pancreata were transplanted into the 8 recipients in Group 1, while only 4 pancreata were required to supply islets for the 4 recipients in Group 2. The mean number of HLA-A, B and DR mismatches was 5.0 in Group 1 and 4.8 in Group 2, although the total number of HLA disparities in Group 1 exceeded those of Group 2 due to the use of multiple donors in these patients. The in vitro glucose-stimulated insulin secretory response stimulation index was similar in the two groups, as was islet purity and viability (Table 2).

Insulin independence

In Group 1, two subjects received single donor transplants, five received 2 islet cell infusions and one received 3 islet cell infusions (mean 1.7 +/− 0.6), whereas the four recipients in group 2 received 1 infusion each. The total islet mass infused/recipient body weight (IEQ/kg) was higher in Group 1 than Group 2 (16,636 +/− 1,929 IEQ/kg vs. 8,179 +/− 1784 IEQ/kg), although the mass of the first islet infusion did not differ between the groups 9,605 +/− 5091 vs. 8,179 +/− 1,784.

Using the metrics developed by the NIH Clinical Islet Transplant Consortium, we evaluated the rates of insulin-independence in the two groups 75 days after the initial islet infusion and after the completion transplant. In Group 1, all subjects experienced islet function defined as initial C-peptide detection ≥ 0.5 ng/ml, but only 2/8 subjects were insulin independent with a single donor transplant. Each of the four subjects in Group 2 achieved insulin independence with positive c-peptide response, and HbA1c was normalized by day 75 in 3 subjects.

In both groups the MMT demonstrated a non-diabetic response to glucose stimulation (postprandial BG ≤ 180mg/dl) with appropriate stimulated C-peptide response in all subjects who demonstrated insulin independence (Table 3). In Group 1 the mean fasting and stimulated C peptide was 0.89ng/ml (range 0.7–1.5 SD 0.34) and 1.96ng/ml (range 0.8– 5.0 SD 1.44) respectively. In Group 2 the mean fasting and stimulated C peptide was 1.43ng/ml (range 0.8–1.9 SD 0.46) and 1.22ng/ml respectively (range 1.1– 4.0 SD 1.27).

Table 3.

Outcomes at primary endpoint

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Body Mass Index | 21.8 | 20.0 | 22.2 | 19.9 | 23.5 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 17.7 | 20.1 | 22.8 | 23.5 | 21.4 |

| Total Islet Mass/kg | 12269 | 19379 | 14898 | 15959 | 12679 | 18989 | 16496 | 18768 | 8041 | 9901 | 8815 | 5722 |

| Number of Transplants | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| WBC (10E3/mcL) | 3.4 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 18.4 | 9.1 | 5.7 | 5.1 |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 12.3 | 13.4 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 8.8 | 13.3 | 15.2 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) | 36 | 24 | 61 | 29 | 33 | 17 | 30 | 16 | 15 | 10 | 22 | 25 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) | 37 | 24 | 50 | 32 | 35 | 23 | 17 | 24 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 24 |

| Daily insulin (Units/kg) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.8 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.7 |

| Change in HbA1c from Baseline | 0.1 | 1.3 | −1.2 | −1.5 | −0.5 | −1.3 | −0.2 | −1.2 | −0.2 | −1.4 | −1.0 | −1.6 |

| Fasting c-peptide (ng/ml) | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Stimulated c-peptide (ng/ml) | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 1.6 |

| Class I / II PRA | 25/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/53 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

| DSA | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

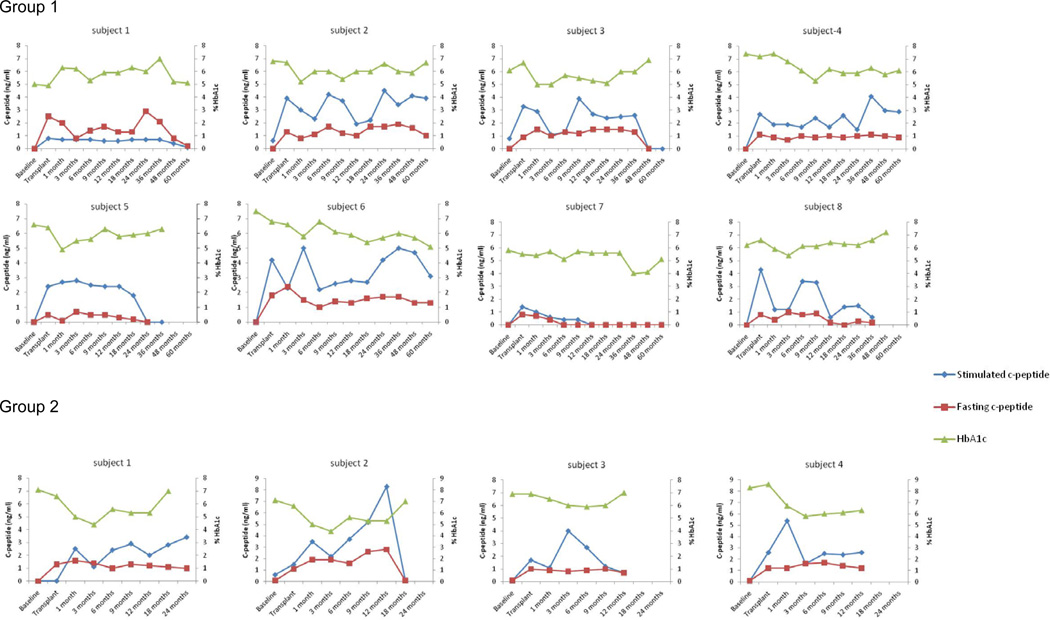

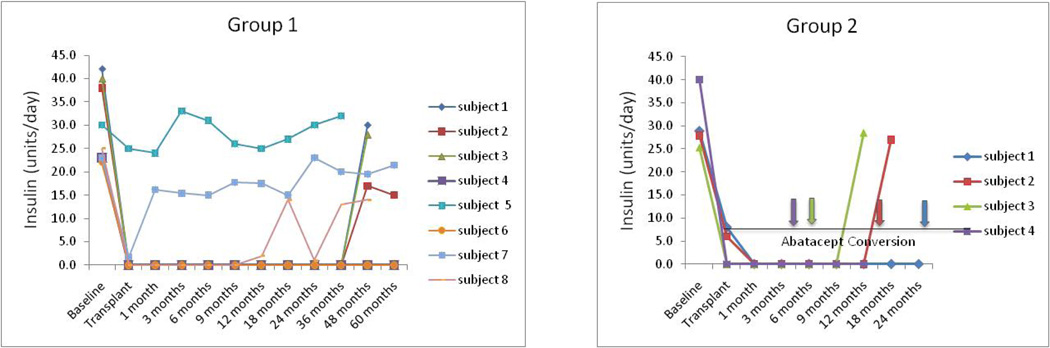

In Group 1, 6 of 8 subjects ultimately became insulin independent with a c-peptide >0.5 and a normal HbA1c after the completion transplant (Table 3; Figures 1 and 2). At 60 months follow-up, Subjects 4 and 6 continue to have complete graft function (insulin independent, HbA1c ≤ 6.5). The fasting and stimulated C-peptide at 60 months was 0.9 and 1.3, and 2.9 and 3.1 respectively. At > 60 months subjects 1 and 8 have partial graft function with significantly reduced insulin requirements, c-peptide >0.5 and a normal HbA1c. Subjects 2 and 3 showed insulin independence for 36 months and graft function for 48 and 36 months respectively.

Figure 1.

Stimulated c-peptide (blue), fasting c-peptide (red), and HbA1c (green) in all patients treated in this study.

Figure 2.

Insulin levels in all patients treated in this study. Arrows indicate times at which Group 2 patients were discontinued from efalizumab and converted to abatacept (patients 2–4) or voluntarily withdrew from immunosuppression (Subject 1).

As noted above, no subjects in Group 2 required repeat infusions to achieve insulin independence. The median duration of follow-up was 15 months (range 12–36 months). During the course of the trial, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market by the manufacturer (discussed below). Our four subjects were 26, 12, 6, and 4 months post-transplant at the time of efalizumab withdrawal. After informed consent, the subjects were withdrawn from efalizumab (as required) and converted to abatacept, a CD28 costimulation inhibiting fusion protein approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Subject 1 remained insulin independent for 29 months. At 24 months follow-up, HbA1c was 6.4 and fasting and stimulated C-peptide was 1.0 and 3.4, respectively. At 26 months post islet cell infusion efalizumab was converted to abatacept. Subject 1 voluntarily withdrew from the study at 29 months and returned to insulin therapy rather than convert to abatacept. Prior to withdrawal the HbA1c was 5.8. Subject 2 achieved insulin independence for 16 months. At 12 months HbA1c was 5.9 and fasting and stimulated C-peptide was 2.8 and 8.3, respectively (Figures 1 and 2). Subject 2 experienced graft failure 4 months and 7 days after conversion to abatacept. Subject 3 was insulin independent for 9 months post islet infusion and experienced graft failure 3 months and 12 days after conversion to abatacept. Subject 4 was converted to abatacept 4 months after transplant with sirolimus added 2.5 months after starting abatacept. Subject 2 continues to be insulin independent 16 months after single islet infusion on abatacept, MMF and sirolimus with HbA1c of 6.0 and fasting and stimulated C-peptide of 1.2 and 2.6 (Figures 1 and 2).

Adverse Events

There were no deaths, cancers or opportunistic infections in either group. Because of the differences in the duration of treatment on protocol and overall follow-up we compared the incidence of overall serious adverse events (SAEs), adverse events (AEs) and events of special interest in islet transplantation (leukopenia, anemia, peri-infusional elevations of serum liver enzyme concentrations, renal function, mouth ulcers, diarrhea and incisional hernias) at 75 days and six months. We also describe the overall SAEs and AEs for the complete follow-up of each group.

At the primary 75-day endpoint there were a total of 161 adverse events (20 AEs/subject) in Group 1 including 43 adverse events grade 2 or greater (5.4/subject). In Group 2 there were 27 total adverse events (6.8/subject) including 13 grade 2 or greater (3.3/subject). Similarly, the rate of AE’s in Group 1(80 total, 10/subject) was higher than in Group 2 (16 total, 4/subject) at 6 months.

The incidence of events of special interest at the 75-day endpoint is summarized in Table 4. There was a significant reduction (p=0.02) in morbidity associated with these immunosuppression related events in the subjects receiving efalizumab compared to subjects treated with the Edmonton protocol. Ultimately all subjects in Group 1 were converted from sirolimus to mycophenolate mofetil because of sirolimus-associated toxicities. Notably the subjects in Group 2 did not experience leukopenia, mouth ulcers, incisional hernias, and diarrhea. Only 2/4 experienced peri-infusional elevation of liver enzymes which were rated as grade 1. All subjects in Group 1 experienced peri-infusional elevation in LFT’s with 5/8 having a rating of grade 2 or greater. There was a statistically significant difference in the peak peri-infusional LFT values between the two groups (mean AST Group 1 158.13, Group 2 59.50, p = 0.03, mean ALT Group 1 164.88, Group 2 64.50, p= 0.03). There was no difference in LFT measurements at other time points.

Table 4.

Adverse events at primary endpoint

| Leukopenia | Anemia | LFT’s | Diarrhea | Mouth Ulcers |

Hernia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 8 / 8 | 8 / 8 | 8 / 8 | 7 / 8 | 5 / 8 | 5 / 8 |

| Group 2 | 0 / 4 | 2 / 4 | 2 / 4 | 0 / 4 | 0 / 4 | 0 / 4 |

There were no clinical opportunistic viral infections in either group. No routine viral load monitoring was performed in Group 1. In Group 2 routine whole blood EBV viral loads was assessed monthly. Three of four subjects in Group 2 developed detectable EBV, but none developed clinical signs or symptoms (Table 5). The EBV viral load decreased from 3300 to 1800 copies in subject 1 and from 3600 to 1000 copies in subject 2 after lowering the efalizumab and MMF dose by half. Subject 4 was monitored closely with no change in drug dosages and currently has an undetectable EBV viral load. Subject 1 and Subject 4 had a further decrease in EBV viral load once tacrolimus was discontinued. None of the three subjects developed clinical EBV disease. There was no PTLD in either group of subjects. JC viral load was also tested in Group 2 upon notification of PML occurring in psoriasis subjects taking efalizumab. All measurements were negative.

Table 5.

EBV viral load

| Group 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Baseline | <140 | Undetected | Undetected | ND |

| Transplant | 190 | Undetected | ND | Undetected |

| 3 months | 3300 | 3600 | Undetected | 5500 |

| 6 months | 650 | 380 | ND | 950 |

| 9 months | 2000 | 8900 | <300 | 330 |

| 12 months | 4400 | 32000 | Undetected | Undetected |

| 18 months | 1400 | 1000 | ND | ND |

| 24 months | 1800 | ND | ND | ND |

| Highest Level | 4400 | 77200 | <300 | 5500 |

Normal < 300 copies/ml

ND= Not determined

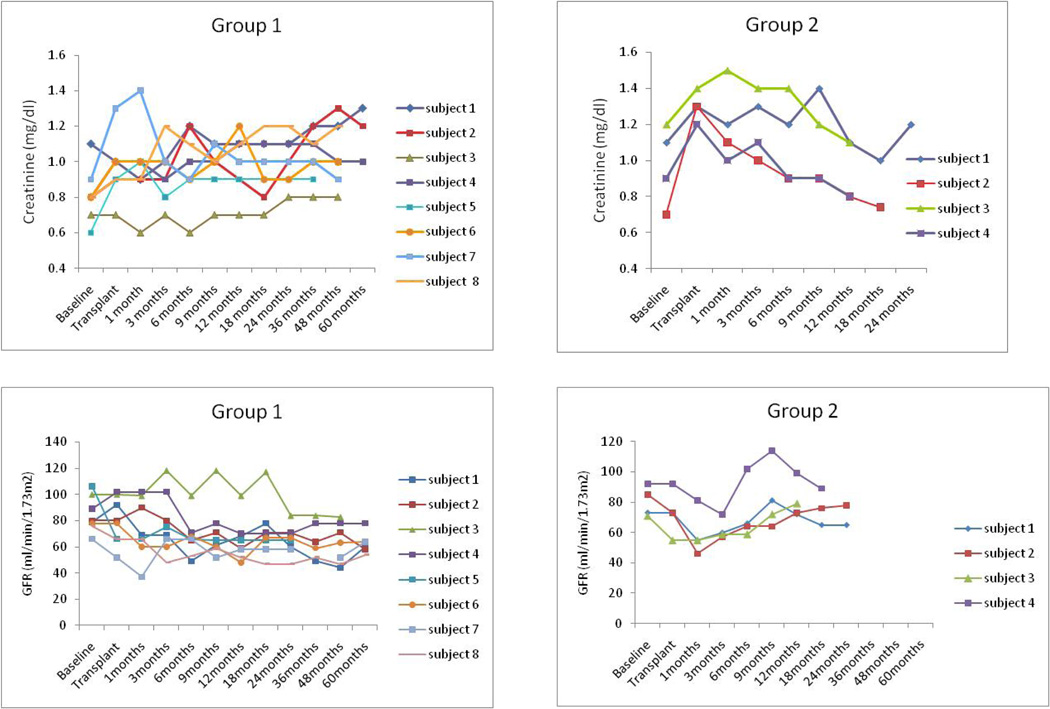

There were no clinically significant changes in renal function (Figure 3). Four of eight subjects in Group 1 developed donor specific antibodies (DSA) (Table 6). Thus far, none of the subjects in Group 2 have developed DSA.

Figure 3.

Serum creatinine levels and calculated GFR using MDRD calculation in all patients treated in this study.

Table 6.

Class I / II PRA and DSA

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Baseline | 25/00 | 00/00 | 11/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

| Day 75 | 25/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/53 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

| 1 year | 27/00 | 00/00 | 06/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/40 | 99/93 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/08 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

| Post IS Change | 08/00 | 00/00 | 83/75 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 21/00 | 99/93 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/13 | 00/00 | NA |

| Post Graft Loss | NA | 00/00 | 78/73 | NA | 92/18 | NA | 95/99 | 00/00 | ND | 00/11 | ND | NA |

| Current | 21/00 | 00/00 | 97/97 | 06/00 | 92/18 | 12/00 | 99/99 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 | 00/00 |

| DSA Day 75 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| DSA Current | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

IS = Immunosuppression

ND = Not determined

NA = Not applicable, no graft loss to date

DISCUSSION

The findings from our series of patients receiving islet allografts and the Edmonton protocol closely reproduced the findings of the Edmonton group and other centers using this approach. Some subjects enjoyed complete and prolonged graft function and insulin-independence more than 6 years, but most lost graft function despite immunosuppressive regimen compliance. Infusions of islets from multiple donors typically were required to achieve insulin independence, and there was a uniform and high rate of protocol-related toxicities, and allosensitization in 50% of patients to date. In contrast, patients treated with an efalizumab-based regimen had successful reversal of diabetes using islets from single donors, reduced rates of toxicity, and no allosensitization. This trial was unavoidably truncated due to the withdrawal of efalizumab from the market. Nevertheless, the potency of efalizumab in maintaining islet function was further suggested by the failure of islet allografts after discontinuation of efalizumab in 3 or 4 patients. While conclusions from this pilot experience should be made with due caution, our results may indicate that islets can be successfully transplanted without T cell depletion, sirolimus, steroids or long-term tacrolimus maintenance therapy, and suggest that efalizumab is efficacious in preventing rejection. We recognize that the treatment groups are sequential, and the change in enzyme blend may have influenced outcomes. Certainly, the improved toxicity profile without a decrement in efficacy in efalizumab-treated patients provides encouragement for protocols that spare or avoid sirolimus and CNIs.

The immunosuppressive properties of efalizumab may have particular advantages in islet transplantation. Efalizumab inhibits T cell function at multiple levels by blocking T cell adhesion to antigen presenting cells, destabilizing the immune synapse, preventing LFA-1 mediated activation signals, and denying T cells access to areas of inflammation and antigen presentation. In addition, efalizumab’s efficacy in ongoing autoimmune conditions such as psoriasis suggests that it inhibits memory cell responses. Interestingly, elevations of liver enzymes typically seen at the time of islet infusion in Edmonton protocol treated patients were conspicuously absent in the efalizumab treated subjects, suggesting that there was less liver inflammation perhaps through reduced trafficking of T cells to the sites of islet implantation. This may be an important factor facilitating better initial engraftment that requires further targeted research.

The rejection of islet allografts in 2 of 3 subjects after conversion from efalizumab to abatacept suggests that CD28-specific costimulation blockade may be of limited effectiveness in preventing islet rejection. Abatacept was selected to minimize the toxicities of currently available immunosuppressive agents and was based on successful conversion to abatacept in a small number of kidney transplant recipients at our center who were unable to tolerate tacrolimus or sirolimus. Abatacept appears incompletely effective in maintaining islet allografts. This is consistent with our ongoing non-human primate studies comparing abatacept with the second-generation CD28 costimulation blocker, belatacept. While it might have been preferable to offer subjects in this trial belatacept, that option was not available to us. It is possible that the rejection of islets after conversion to abatacept may not entirely reflect the lack of potency of abatacept. It has been reported that discontinuation of efalizumab can result in flares of disease activity in psoriatic subjects.

The lack of allosensitization during efalizumab therapy is encouraging as this is a significant problem in existing islet transplant trials. The prolonged lack of allosensitization despite islet loss may, however, be a reflection of the potency of costimulation blockade (abatacept) in preventing T cell dependent antibody responses (18). Given that allosensitization is a significant concern in ITx, this property of abatacept is attractive and may be a useful adjuvant when withdrawing immunosuppression from allograft recipients.

The safety of efalizumab certainly requires close scrutiny. During the conduct of our trial, the sponsor voluntarily withdrew efalizumab from the market and halted all efalizumab-based studies after 4 cases of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) were reported related to long-term (> 4 year) efalizumab use in approximately 40,000 patients with psoriasis. Interestingly, the safety signal for PML was quite specific with few cases of other opportunistic infections such CMV and EBV in the psoriasis experience. Nonetheless, given that non-life threatening nature of psoriasis and the availability of alternative therapies, the risk benefit ratio for efalizumab could not justify its continued use for that condition. The risk to benefit ratio is substantially different in patients with brittle T1DM, a lethal condition in which the prevailing standard therapies (both transplantation and tight control with exogenous insulin) have substantial toxicities greatly exceeding the currently reported PML risk. Interestingly, the risks of serious viral infections including PML are well established for commonly used immunosuppressive agents in transplantation including anti-thymocyte globulin, MMF, and rituximab (19–21). This suggests that the use of efalizumab may well be appropriate in T1DM and other transplant indications. Access to this, or similar reagents should be considered in appropriately controlled clinical trials.

In summary, carefully selected patients with T1DM can be rendered insulin independent after a single islet infusion with the novel immunosuppressive regimen reported herein. This regimen was associated with markedly lower rates of adverse events typically associated with islet transplantation. These data suggest that a critical appraisal of efalizumab in islet transplant is warranted. Carefully designed studies could potentially define an appropriate duration of therapy that would take advantage of the favorable properties of efalizumab, while minimizing risks in an effort to improve transplant outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Clinical Islet Transplant Program receives funding from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), Clinical Islet Transplant Consortium (CIT) and Genentech and is supported in part by PHS Grant UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program and PHS Grant M01 RR0039 from the General Clinical Research Center program, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources.

Funding Sources: JDRF, Genentech, General Clinical Research Center program

REFERENCES

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004 May;27(5):1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Diabetes. 1997 Feb;46(2):271–286. 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacqueminet S, Masseboeuf N, Rolland M, Grimaldi A, Sachon C. Limitations of the so-called "intensified" insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2005 Sep;31(4 Pt 2):4S45–4S50. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(05)88267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 27;343(4):230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolls MR, Gill RG. LFA-1 (CD11a) as a therapeutic target. Am J Transplant. 2006 Jan;6(1):27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriyama H, Yokono K, Amano K, Nagata M, Hasegawa Y, Okamoto N, et al. Induction of tolerance in murine autoimmune diabetes by transient blockade of leukocyte function-associated antigen-1/intercellular adhesion molecule-1 pathway. J Immunol. 1996 Oct 15;157(8):3737–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herold KC, Vezys V, Gage A, Montag AG. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes by treatment with anti-LFA-1 and anti-ICAM-1 monoclonal antibodies. Cell Immunol. 1994 Sep;157(2):489–500. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury SA, Nagata M, Yamada K, Nakayama M, Chakrabarty S, Jin Z, et al. Tolerance mechanisms in murine autoimmune diabetes induced by anti-ICAM-1/LFA-1 mAb and anti-CD8 mAb. Kobe J Med Sci. 2002 Dec;48(5–6):167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poston RS, Robbins RC, Chan B, Simms P, Presta L, Jardieu P, et al. Effects of humanized monoclonal antibody to rhesus CD11a in rhesus monkey cardiac allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2000 May 27;69(10):2005–2013. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonardi C, Menter A, Hamilton T, Caro I, Xing B, Gottlieb AB. Efalizumab: results of a 3-year continuous dosing study for the long-term control of psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008 May;158(5):1107–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froud T, Ricordi C, Baidal DA, Hafiz MM, Ponte G, Cure P, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus using cultured islets and steroid-free immunosuppression: Miami experience. Am J Transplant. 2005 Aug;5(8):2037–2046. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Finke EH, Olack BJ, Scharp DW. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 1988 Apr;37(4):413–420. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichii H, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Baidal DA, Khan A, Kuroda Y, et al. Rescue purification maximizes the use of human islet preparations for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005 Jan;5(1):21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bray RA, Lebeck LK, Gebel HM. The flow cytometric crossmatch. Dual-color analysis of T cell and B cell reactivities. Transplantation. 1989 Nov;48(5):834–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olerup O, Zetterquist H. HLA-DR typing by PCR amplification with sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) in 2 hours: An alternative to serological DR typing in clinical practice including donor-recipient matching in cadaveric transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 1992;38:255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tambur AR, Bray RA, Takemoto SK, Mancini M, Costanzo MR, Kobashigawa JA, et al. Flow cytometric detection of HLA-specific antibodies as a predictor of heart allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2000 Oct 15;70(7):1055–1059. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200010150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, Rostaing L, Bresnahan B, Darji P, et al. A Phase III Study of Belatacept-based Immunosuppression Regimens versus Cyclosporine in Renal Transplant Recipients (BENEFIT Study) American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10(3):535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calabrese LH, Molloy ES. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in the rheumatic diseases: assessing the risks of biological immunosuppressive therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec;67(Suppl 3):iii64–iii65. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirk AD, Cherikh WS, Ring M, Burke G, Kaufman D, Knechtle SJ, et al. Dissociation of depletional induction and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in kidney recipients treated with alemtuzumab. Am J Transplant. 2007 Nov;7(11):2619–2625. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neff RT, Hurst FP, Falta EM, Bohen EM, Lentine KL, Dharnidharka VR, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and use of mycophenolate mofetil after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2008 Nov 27;86(10):1474–1478. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818b62c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.