Abstract

Until now, the lack of a means to detect a deficiency or to measure the pharmacologic effect in the human brain in situ has been a hindrance to the development of antioxidant-based prevention and treatment of dementia. In this study, a recently developed 1H MRS approach was applied to quantify key human brain antioxidant concentrations throughout the course of an aggressive antioxidant-based intervention. The concentrations of the two most abundant central nervous system chemical antioxidants, vitamin C and glutathione, were quantified noninvasively in the human occipital cortex prior to and throughout 24 h after bolus intravenous delivery of 3 g of vitamin C. Although the kinetics of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter and physiologic blood vitamin C concentrations predict theoretically that brain vitamin C concentration will not increase above its homeostatically maintained level, this theory has never been tested experimentally in the living human brain. Therefore, human brain vitamin C and glutathione concentrations were quantified noninvasively using MEGA-PRESS double-edited 1H MRS and LCModel. Healthy subjects (age, 19–63 years) with typical dietary consumption, who did not take vitamin supplements, fasted overnight and then reported for the measurement of baseline antioxidant concentrations. They then began controlled feeding which they adhered to until after vitamin C and glutathione concentrations had been measured at 2, 6, 10 and 24 h after receiving intravenous vitamin C. Two of the twelve studies were sham controls in which no vitamin C was administered. The main finding was that human brain vitamin C and glutathione concentrations remained constant throughout the protocol, even though blood serum vitamin C concentrations spanned from the low end of the normal range to very high.

Keywords: antioxidants, ascorbate, glutathione, MRS, noninvasive, human, brain, intravenous

INTRODUCTION

Because multiple lines of evidence implicate oxidative damage as a cause, cofactor or consequence of compromised brain function in normal aging and age-related neurodegenerative disease (1), several epidemiological and prospective studies have investigated the relationship between antioxidant consumption and cognitive function (2). Although the balance of published data suggests that antioxidants reduce the incidence and severity of dementia (3,4), the absence of a tool to follow brain antioxidant concentrations in living humans has hindered the development of an effectual intervention. The lack of ability to measure a pharmacologic effect is a documented hindrance to the development of antioxidant-based interventions against dementia (3). Given a recent finding that only when systemic antioxidants were depleted at baseline could a benefit of antioxidant-based treatment be realized (5), it follows that the inability to measure baseline antioxidant concentrations in the human brain has also been a hindrance to the development of interventions.

Recently, a method for the detection of MRS resonances from two important antioxidants in the human brain in situ has been developed (6), and the concentrations quantified from these resonances have been substantiated (7–11). Ascorbate (Asc) and glutathione (GSH) are the two most concentrated chemical antioxidants in the human central nervous system, and together they are associated with four of the six most recognized antioxidant systems. The compartmentalization of Asc predominantly to neurons and of GSH predominantly to glia (12) suggests that sufficient concentrations of both are important for neuroprotection. However, the capacity for Asc and GSH to regenerate one another (13) and the transport mechanisms available between neurons and glia (14) suggest that the sum of these concentrations may be a better indicator of antioxidant capacity. Although the micromolar concentration of vitamin E, an important membrane antioxidant, is below the detection threshold of in vivo 1H MRS, Asc spares and restores the antioxidant capacity of vitamin E (13,15,16), suggesting that Asc may provide a surrogate marker of the antioxidant capacity of vitamin E. GSH supports the maintenance of Asc in its reduced state and is a substrate for the important antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase. Given that Asc and GSH are associated with two-thirds of the predominant antioxidant systems, the MRS-measured antioxidant profile reflects a substantial proportion of brain antioxidant capacity.

The delivery of Asc to the brain via the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the kinetics of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter (SVCT2), which regulates the uptake of Asc from the CSF into the brain, have been studied extensively (17). The Km value for SVCT2 is within the typical range of blood serum Asc concentrations ([Asc]serum), and is therefore ideally suited to homeostatically concentrate brain Asc to a basal level that is not expected to increase after vitamin C supplementation. However, vitamin C homeostasis has never been demonstrated experimentally in the human brain. The objective of this project was to quantify brain Asc concentration ([Asc]brain) in human subjects with [Asc]serum within and above the normal range. The approach was to administer an acute intervention that caused [Asc]serum to go from the low end to well above the normal range in each of several healthy subjects. Our methods accommodated the simultaneous quantification of GSH with Asc. Therefore, human [Asc]brain and brain GSH concentration ([GSH]brain) were followed prior to and throughout 24 h after treatment with an effective (i.e. intravenous, IV) bolus delivery of the ‘lowest observed adverse effect level’ (18) of vitamin C.

EXPERIMENTAL DETAILS

Protocol

All study components were approved in advance by the human subjects’ protection committee at the University of Minnesota, and all subjects provided informed consent. Candidates were screened with regard to health status, diet, supplementation, smoking and metal implants. Qualified participants were instructed to avoid vitamin C supplementation for at least 1 week prior to MRS and to begin fasting when they went to bed the night before the study. Asc and GSH concentrations were measured prior to and 2, 6, 10 and 24 h after IV administration of vitamin C to avoid missing a transient change or a longer term effect. After 24 h, given the 10-day half-life of Asc in the body (19), no further changes were expected. A total of five MRS sessions were performed over approximately 24 h, i.e. at baseline, 2, 6, 10 and 24 h. All subjects reported to the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR) at the University of Minnesota between 7:51 and 10:45 AM for baseline quantification of antioxidant concentrations. Next, they reported to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) of the University of Minnesota to submit a baseline blood sample and to receive the 3-g bolus (delivered over 15–17 min) of IV vitamin C, which was begun 2 h and 14 min (on average) after beginning the antioxidant-detecting portion of the baseline MRS. Whilst under observation, subjects began controlled feeding that continued throughout the remaining 24 h of the protocol. After submitting the first post-infusion blood sample, subjects were transported to CMRR for MRS. The time elapsed between the start of the delivery of vitamin C and the start of the antioxidant portion of MRS was 2 h and 17 min on average. Subjects were removed from the scanner to rest and wait for the 6-h MRS (the average time between the start of IV vitamin C and the start of the antioxidant portion of MRS was 6 h and 2 min), which was preceded by blood sampling. The 10-h MRS (average time between the start of IV vitamin C and the start of the antioxidant portion of MRI was 9 h and 47 min) was completed analogously. Subjects went home for the night and then reported for the 24-h blood sample and MRS (23 h and 55 min after the start of IV vitamin C). Subjects submitted dietary compliance documentation before release.

Subjects

Eleven healthy adults [three men and eight women; age, 28 ± 13 years (mean ± SD); body mass index, 24 ± 3 kg/m2 (mean ± SD); n = 12], one of whom was both treated and studied as a sham, were recruited using flyers posted throughout the University of Minnesota and postings at research volunteerism websites. Individuals with typical fruit and vegetable consumption, which was below the recommended daily allowance, were recruited because, putatively, they had lower antioxidant reserves and thus a greater likelihood of responding to treatment with an increase in brain antioxidant concentration (5). Subjects with advanced-stage dementia were excluded to avoid the possible depletion of brain antioxidants via neurodegenerative disease. Candidates were prescreened using a telephone interview to rule out vitamin C supplementation, atypical dietary habits, smoking, the presence of metal implants or chronic illness. The candidates then reported to GCRC for a more thorough screening that included a questionnaire, a wellness examination and laboratory work. Pregnancy (women) was tested and affirmed to be negative immediately prior to the IV administration of vitamin C. Ten subjects completed the protocol including treatment with vitamin C. Two sham studies in which no vitamin C was delivered and no IV was placed were also completed. One of the sham studies was completed by a subject who completed the treatment study 2 months prior to participating as a sham, and the other sham study was completed by a subject who never received IV vitamin C.

Dietary management of vitamin C

To ensure consistency among subjects, a diet designed to contain the recommended dietary allowance, 30 mg of vitamin C per 1000 kcal, was provided to all subjects over the 24 h following the vitamin C infusion. An estimate of total energy needs for each participant was made by the calculation of the resting basal energy expenditure (REE) using the Harris Benedict equation and adjustment for daily activity. The minimal energy needs for all participants was based on REE × 1.6; higher levels of adjustment were used for participants who reported strenuous physical activity. As the diets were isoenergic, subjects were asked to consume all of the diet provided and no other foods or beverages. All foods were prepared in the metabolic kitchen of GCRC. In order to minimize differences in the metabolism of vitamin C, subjects were asked to abstain from strenuous activity over the 24 h after vitamin C infusion. Subjects were required to document compliance to the study diet. Deviation from compliance was calculated on the basis of the self-reported foods consumed, and quantified relative to the total calories and vitamin C provided.

IV vitamin C

IV administration was utilized because it can induce much higher [Asc]serum than can be achieved orally (20); 3.375 g of sodium ascorbate (CENOLATE®, Ascorbic Acid Injection, USP, 500 mg/mL; Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) was dissolved in 250 cm3 of Ringer’s lactate solution under full sterile conditions in the investigational pharmacy on the morning of the study. Within 2.25 h of preparation, it was delivered to the subject intravenously over 15–17 min. Local cooling was applied to prevent thrombophlebitis (21).

Serum Asc concentration

Blood vitamin C concentrations were measured in conjunction with each MRS. For this assay, a saline lock was placed in the arm contralateral to that in which the sodium ascorbate was delivered; 8 mL of whole blood was collected in a tube containing sodium heparin (preservative) and placed immediately on wet ice. Serum was separated immediately at 21°C and aliquoted into preservative. Ampoules were submitted frozen (−70°C) to ARUP Laboratories, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) for analysis by spectrophotometry.

MRS protocol

Images and spectra were measured using a 4-T, 90-cm horizontal bore MR scanner (Siemens/Oxford Magnet Technology, Oxford, UK) interfaced to a Varian INOVA spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The magnet was equipped with a gradient system (40 mT/m, 400 μs rise time) which included second-order shim coils with maximum shim strengths of XZ = YZ = 5 Hz/cm2, Z2 = 12 Hz/cm2 and XY = X2 − Y2 = 2.5 Hz/cm2. Pre-emphasis was used (22). Shim coil currents were controlled using amplifiers from Resonance Research, Inc. (Bellerica, MA, USA). The radio-frequency (RF) amplifiers (CPC, Brentwood, NY, USA) provided maximum power of 2.6 kW at the coil. A half-volume 1H surface coil (23) combined with quadrature hybrids, with a fixed 90° phase shift, was used for RF signal transmission and reception. The two geometrically decoupled circular RF coil loops were both 14 cm in diameter. The maximum transmit B1 field was just above 40 μT in the center of the occipital lobe. For each MRS session, the subject was positioned supine inside the magnet with the RF transceiver subjacent to the occipital lobe. The protocol for each MRS session began with localizer multislice anatomic MRI [rapid acquisition relaxation enhancement mode; TR = 4.0 s; TE = 60 ms; echo train length, 8; matrix, 256 × 128; two averages; slice thickness, 2 mm; five slices) to select a cubic volume of interest (VOI, 3 × 3 × 3 cm3) centered on the mid-sagittal plane in the occipital lobe. Consistency in positioning the human brain within the magnet bore was standardized using three points of reference. The external occipital protuberance was laid over the marked coil center. The bridge of the nose and the middle of the chin were used to define the median plane, which was centered in the bore to ensure that the midline of the brain was parallel to the axis of the magnet. Once subjects were lying in this position, superficial marks were placed on the forehead (laser-guided cross-hairs) from above, and on the ear and chin from the side (relative to solid features of the RF coil). These marks were reinforced before each MRS session and used to position the subject identically for all MRS. For the first MRS session, the subject was moved into the magnet until the VOI was at the isocenter. The lateral boundaries of the VOI were chosen to place the average midline of the occipital lobe in the center of the VOI. The remaining boundaries were set to keep the VOI outside the cerebellum, but inside the skull. The images measured at baseline were used to set the boundaries of the VOI for subsequent MRS sessions. Spectra were measured from the occipital lobe, because delivery via the CSF (24) may render Asc availability most variant in the cortex, and because the sensitivity of measurement of the spectra is highest in superficial regions. The adjustment of all first- and second-order shim currents to optimize B0 homogeneity in VOI was achieved using FASTMAP with echo planar imaging readout (25). The homogeneity achieved resulted in a 9-Hz linewidth on average (range, 7–12 Hz). Anatomic MRI was repeated at the end of the MRS session to make sure that the subject did not move, i.e. that spectra were, indeed, measured from the intended VOI (assuming the subject did not move away from and then back into the same position over the course of the study). Motion was also continuously monitored indirectly via changes in linewidth and chemical shift of the prominent N-acetylaspartate (NAA) resonance in the sub (i.e. presubtracted) spectra (6). Each MRS session took approximately 1.5 h.

1H MRS

Double editing for Asc and the cysteine residue of GSH (2.95 ppm) was achieved using a slight modification (11) of double editing with (DEW) MEGA-PRESS, as described previously (6). Water suppression and outer volume saturation were applied (26). Slice-selective excitation was achieved using a 2-ms sinc RF pulse with a bandwidth (full width at half-maximum) of 2.0 kHz. Slice-selective refocusing used a 3-ms sinc RF pulse with a bandwidth of 1.5 kHz. DEW MEGA-PRESS spectra were collected at TR = 4500 ms and TE = 102, 112, 122, 132, 142 and 152 ms. Detection over a range of TE in each MRS session was a new development that retained the same detection sensitivity, but reduced complications from coedited compounds and allowed the calculation of T2 (11). Knowledge of T2 would allow the testing of assumptions typically used for quantification. The chemical shift (ppm) and length of the DEW MEGA-PRESS editing pulses were adjusted to accommodate each TE as detailed in Table 1. For each person and MRS session, 96 excitations were repeated at each TE in an interleaved fashion. The RF power (B1) of the 40-ms editing pulse was calibrated by placing the center frequency on water and incrementing B1 until the resonance from water was minimized (27). The B1 values for the other editing pulses were calculated relative to the B1 value of the 40-ms editing pulse based on the well-known relationship between pulse length and power required to achieve inversion. The chemical shifts of the editing pulses were adjusted whenever the B0 drift exceeded ± 10 Hz to avoid contamination of the edited Asc resonance (9) and to keep Asc editing efficiency loss under 8%. The spectral width was 6000 Hz and 4035 complex points were acquired for each spectrum. Spectra were zero filled to 32,768 points, Fourier transformed using a Gaussian time constant of 0.15 s and displayed in phase-sensitive mode. Each single free induction decay was stored separately in memory, and then the frequency and phase of each free induction decay were corrected on the basis of the NAA methyl signal prior to summation of all spectra measured at all TE for a given person and MRS session.

Table 1.

TE and respective chemical shifts (f) and lengths (l) of Gaussian editing pulses

| TE (ms) | 102 | 112 | 122 | 132 | 142 | 152 |

| fAsc (ppm) | 4.18 | 4.13 | 4.10 | 4.06 | 4.04 | 4.01 |

| lAsc (ms) | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 |

| fGSH (ppm) | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.56 |

| lGSH (ms) | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 |

Asc, ascorbate; GSH, glutathione.

Quantification of Asc and GSH concentrations

The strengths of all of the signals in the edited spectra were measured using LCModel (28) version 6.2 with Asc, GSH, myo-inositol, lactate, NAA, phosphorylcholine, glycerophosphorylcholine and phosphorylethanolamine in the basis set. The baseline was constrained flat (via the ALPBMN parameter). Basis spectra were simulated at each TE using the quantum mechanics density matrix formalism with published values of J-coupling constants and chemical shifts (29). These simulations were performed using Matlab and home-written programs (30). Crusher gradients were simulated by performing simulations across a large range of frequency offsets, and then averaging the resulting magnetization. Shaped pulses were simulated as a series of square pulses. Frequency offset was taken into account in the Hamiltonian using H = ΩIz, where Ω is the frequency offset for spin I. MEGA-PRESS-edited spectra simulated as such have been shown to be in good agreement with those measured from pure solutions (11). The basis spectrum for each metabolite was created by summing the spectra simulated at all six TEs after weighting them for the same in vivo T2 relaxation for all subjects and scans [56 ms for Asc (11), 67 ms for GSH (11) and 190 ms for all other compounds based on the range of previously reported values for NAA (31), glutamate (32) and creatine (32)]. Concentrations were calculated using 10 μmol/g NAA as an internal reference, as described previously (6). The calculation of in vivo Asc and GSH (antioxidant) concentrations was based on the assumption that differences between the T2 relaxation of NAA and the T2 relaxation of the antioxidant had the same impact on resonance intensity in vitro and in vivo, i.e. the ratio exp[−TE/T2(NAA)]/exp[−TE/T2(antioxidant)] was approximately the same under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Deviation from this assumption would result in a systematic overestimation or underestimation of the measured antioxidant concentrations.

Statistical analysis

The sample size for this study (10 treated subjects) was preset to have 80% power to detect, at the 0.05 level, a true difference in vitamin C concentration larger than 25% between pre- and post-infusion of vitamin C, assuming the variance achieved previously using a very similar method (6). Tests of change from baseline and the confidence intervals (CIs) associated with them were made using a mixed linear model, which generalizes repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), to distinguish the variation between persons in overall level from the variation between persons in changes in antioxidant levels between time points. Confounding was tested by calculating Pearson’s correlation without consideration of multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

1H MRS

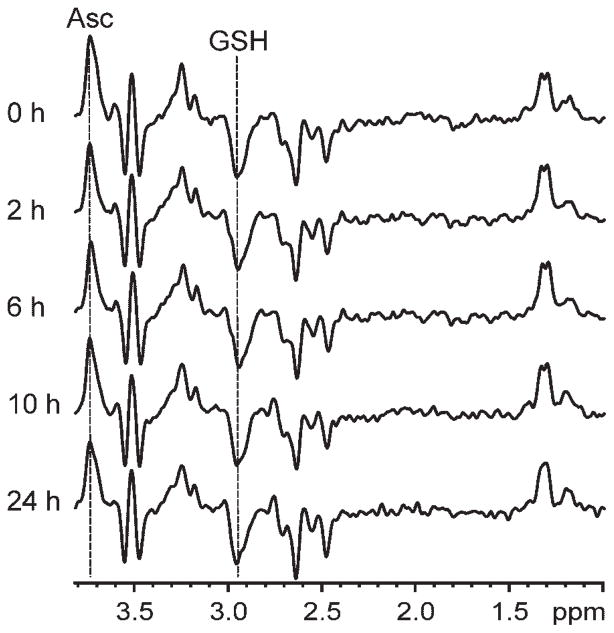

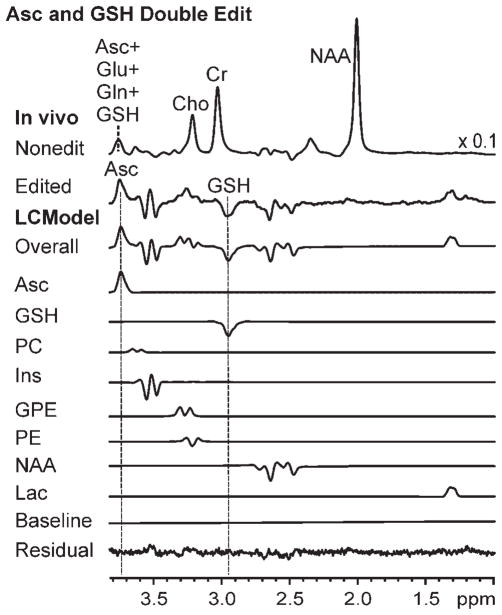

Figure 1 illustrates the double-edited spectra measured from one representative subject prior to and at all four time points after IV administration of vitamin C. Figure 2 illustrates a representative Asc and GSH double-edited spectrum from one subject and one time point and the output of LCModel analysis used to quantify the concentrations therefrom. The average [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain values measured in this study were approximately 1 μmol/g, which agrees with the value of 1 μmol/g measured previously using noninvasive MRS (6,7,11) and the [Asc]brain value measured using invasive post-mortem methods (33). The images contained landmarks that facilitated the demarcation of the same brain region at all time points. Images measured at the end of each MRS session showed no trend for motion in a given direction when averaged over all sessions (average motion <1 mm for each axis). Motion exceeded ±4 mm along a single axis for only two MRS sessions during which each subject moved approximately 7 mm along the magnetic field axis (superior–inferior direction).

Figure 1.

Ascorbate (Asc) and glutathione (GSH) edited MRS (4 T; TR = 4.5 s; number of excitations, 576; TE spanning 102–152 ms) measured from a representative human subject (volume of interest, 27 mL occipital lobe) prior to (i.e. 0 h post-infusion time) and throughout 24 h after intravenous administration of vitamin C.

Figure 2.

Ascorbate (Asc) and glutathione (GSH) edited MRS (4 T; TR = 4.5 s; number of excitations, 576; TE spanning 102–152 ms) measured from a human brain (volume of interest, 27 mL occipital lobe) in vivo during a representative MRS session in this study (21-year-old treated woman at the 2-h time point), and results of quantification via LCModel. In vivo: nonedited spectrum (note scaling of × 0.1 relative to the intensity of the edited spectrum), or sum of spectra measured in the absence and presence of the editing pulse (resonances from a large number of neurochemicals are visible); Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate edited spectrum, i.e. difference between spectra measured in the absence and presence of the editing pulse (resonances from Asc, GSH and several co-edited neurochemicals are visible). LCModel: overall fit of the edited spectrum, fitted components for Asc, GSH, phosphorylcholine (PC), myo-inositol (Ins), glycerophosphorylcholine (GPE), phosphoethanolamine (PE), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), lactate (Lac), baseline component of LCModel fitting, and fitted residual.

Brain response to IV vitamin C

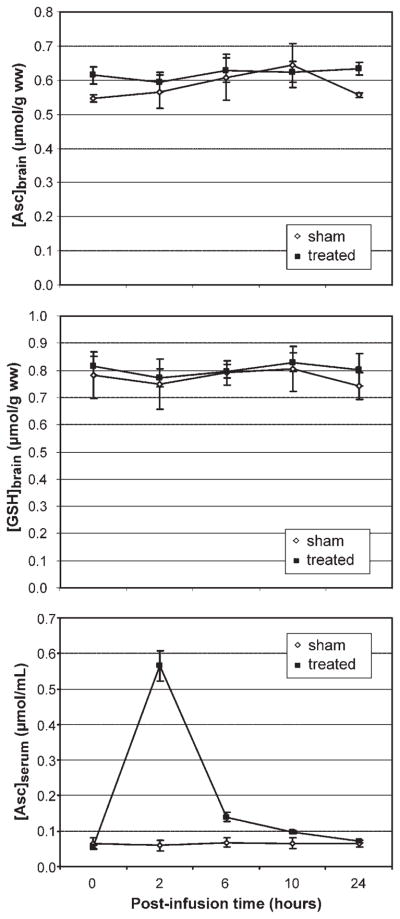

Figure 3 illustrates that no change from baseline [Asc]brain or [GSH]brain was measured (p >0.27 testing for differences between times within the treated group) at any of the time points investigated (2, 6, 10 and 24 h) after IV bolus delivery of 3 g of vitamin C. [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain time courses for the sham and treated groups were no different (p >0.8) based on the interaction of group and time (repeated-measures ANOVA). Measured concentrations were not consistent with a brain antioxidant response of altered [Asc]brain or [GSH]brain of greater than 0.06 μmol/g (95% CI) at any time point. There was no apparent relationship between the extent of motion and either the relative concentrations or the time courses of [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain measured in each individual (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Average [Asc]brain, [GSH]brain and [Asc]serum (mean ± SEM) measured in the sham (n = 2) and treated (n = 10) groups prior to (i.e. 0 h post-infusion time) and at several time points after the intravenous administration of vitamin C. Asc, ascorbate; GSH, glutathione.

Serum Asc

Figure 3 illustrates the range of blood vitamin C concentrations ([Asc]serum) that were studied. The change in [Asc]serum from baseline at the 2-h time point was not correlated (|r|<0.3) with the change in [Asc]brain at any time point in treated subjects. [Asc]brain and [Asc]serum measured at all time points were not correlated (|r|<0.2), independent of whether sham studies were included in the dataset.

Compliance and confounding

Compliance to abstaining from vitamin C supplementation was high (only one individual reported vitamin C supplement consumption), as was compliance to controlled feeding (consumption range 71–100% of calories given, 53–100% of vitamin C given), and compliance to controlled feeding (calories and vitamin C) did not correlate (r2 ≤ 0.5) with the change in [Asc]brain or [GSH]brain at any time point. There was insufficient variance in age among subjects to facilitate testing for confounding by age. There were insufficient men in this group to compare [Asc]brain or [GSH]brain in men vs women.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated experimentally that bolus IV delivery of 3 g of vitamin C to healthy, vitamin C-sufficient human subjects did not disrupt the theoretically predicted [Asc]brain homeostasis. Neither [Asc]brain nor [GSH]brain changed from baseline through-out 24 h after vitamin C delivery. On the basis of the 95% CIs for Asc and GSH concentrations measured before and in response to intervention at any time point, the antioxidant profiling methodology would have been sufficiently sensitive to detect a change as small as 15% post-treatment if this phenomenon had been present in the cohort. Therefore, these data demonstrate that noninvasive 1H MRS can be used to measure antioxidant deficiency and to monitor the pharmacologic effect of antioxidant-based treatment approaches in the living human brain.

The constancy of [Asc]brain after the IV administration of vitamin C is consistent with the slow turnover (34), low absorption (35) and homeostatic mechanisms (36) described. The Km value for the Asc transporter [50–115 μM (17,37)] and the normal [Asc]serum (60 μM before treatment in this study) are approximately the same, which sets up homeostatic maintenance of [Asc]CSF at around 160 μM (17,37). As basal [Asc]CSF is much higher than Km, even if treatment increases [Asc]CSF, there will be no additional transport into brain cells (17,37). However, the same kinetics suggest that circumstances of vitamin C deficiency could lead to a diminished [Asc]brain. [Asc]serum drops as low as 5 μM, i.e. far below Km, in some persons (38,39), which could make [Asc]CSF as low as 20–50 μM (i.e. less than Km) (40), which could then create a circumstance of limited supply of Asc for transport into cells. It is also possible that the number and functionality of SVCT2 could be impacted by changes that take place in the choroid plexus with aging (41) or disease. It is feasible that vitamin C-based intervention would be more effective under these circumstances (5).

Findings from several recent studies have suggested that high levels of brain Asc, as well as its transporter (36), throughout a lifespan are essential to support neuronal development (42–44), cognitive function (38) and protection from oxidative damage (45). In addition to its role as an antioxidant, Asc is an enzyme cofactor and is involved in neurotransmission. Indeed, the mechanism by which acute high doses of vitamin C improve cognition may be associated more strongly with neurotransmitter function than with oxidative stress (43).

The 3-g bolus IV vitamin C protocol is only one among many paradigms that could be investigated. Other protocols, such as more natural (46) or prolonged supplementation, might be more effective. Similarly, interventions designed to have a more specific impact on GSH, or on the total antioxidant capacity, also have the potential to induce a measurable brain antioxidant response.

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the high spectral and fitting quality achieved. The absence of a subtraction artifact from NAA (2.01 ppm) in all edited spectra is evidence of artifact-free difference editing, which is very important in detecting the GSH resonance without confounding from the strong nearby creatine resonance. Indeed, all of the expected resonances appear in the edited spectrum, and all of the resonances in the spectrum can be attributed to co-edited compounds, which demonstrates the absence of unexplained artifacts. The spectral patterns at all pre- and post-infusion time points are highly repeatable, further demonstrating detection in the absence of random artifacts. The constant shape and size of the edited and Asc and GSH resonances at all time points are consistent with the quantification of the same concentrations at all time points, and demonstrate the highly consistent and effective B0 shimming achieved. The absence of discernible resonances from lipids or residual water in the nonedited spectrum (Fig. 2) is evidence of excellent localization and water suppression performance. All spectra show a high signal-to-noise ratio, undistorted lineshapes and a flat baseline, all of which contribute to improved fitting. The absence of discernible resonances in the fitted residual is consistent with the completeness and accuracy of the LCModel basis set, and therefore of high fitting quality.

Given the distribution of Asc [0.1–0.4 mM in CSF, 50 mM in blood, 1 mM in glia and up to 10 mM in neurons (12,14,47,48)] and GSH [0.04 mM in CSF, 0.5–1 mM in whole blood, 3.8 mM in glia and 2.5 mM in neurons (12,49,50)] in cortical brain tissue (approximately 10–20% CSF, 6–10% blood, 25% glia and 49% neurons), signal contributions to the measured [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain in VOI were predominantly intracellular, and contributions from the vasculature were negligible. Using a worst case scenario for Asc [blood volume, 10%; interstitial volume, 20%; glial volume, 25%; neuron volume, 45%; voxel [Asc] = 0.8 μmol/g (6,12)], blood concentrations would have to increase by more than 20-fold (i.e. far more than the less than 10-fold change measured in this study) to cause a 14% change in [Asc]brain measured in VOI (i.e. the largest change that would be consistent with our data). In addition, MRS resonances from molecules that move out of VOI during TE of the signal-generating module cannot be detected. Therefore, signal contributions from the vasculature to the measured [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain were negligible, even though blood Asc concentrations were increased by nearly 10-fold.

Neither theoretical calculations based on the kinetics of SVCT2 nor the data from the present study support the approximately 25% increase in [Asc]brain measured previously in two subjects 10 h after an IV bolus of 3 g of vitamin C using nonedited PRESS (TE = 30 ms) 1H MRS at 3 T (51). On the basis of the 95% CI for [Asc]brain measured at baseline and at 10 h post-infusion, the current data are not consistent with a change in [Asc]brain larger than 15%. To our knowledge, this preliminary finding at 3 T has not been substantiated, although the related matter of the detectability of Asc from standard 1H MRS at 3 T has (52). The advantages of quantifying Asc from nonedited short-TE 1H spectra (TE = 6 ms) measured at high field (7 T) have been described (53,54).

Antioxidant profiling MRS methodology will continue to improve with ongoing improvement in spectroscopic and fitting methods (11,53,55), making it possible to study smaller, deeper and thus more tissue-focused regions of interest, or alternatively to shorten scan times (i.e. making protocols more tolerable and economical). Because of relative concentrations, this assay is sensitive to the intracellular compartment (where Asc functions as an antioxidant and enzyme cofactor) and insensitive to the extracellular compartment (where Asc functions as a neuro-transmitter). As such, this novel methodology has the potential to assist with the elucidation of the mechanisms by which the maintenance of high [Asc]brain levels protect neuronal integrity and cognitive function throughout a lifespan.

Supplementary Material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the onlineversion of this article:

Fig. S1. [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain time courses for each individual subject (shams, S1–S2 and treated probands P1–P10, sham and proband studies S2 ans P2 were both completed by the same person). The error bars are the Cramer Rao Lower Bounds from LCModel. Two scans were not completed because of a power outage. The three symbols denote data points for which overall motion (i.e. the sum over all three axes of the absolute value of how much the subject moved during the scan session) was minor (open diamonds for ≤ 3 mm), moderate (filled diamonds for 4–6 mm) and marked (circled diamonds for 7–9 mm).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the professionalism with which the nutrition and nursing staff at GCRC executed this protocol. We thank Darlette Luke at the pharmacy for assistance in designing and safely executing this protocol, Dianne Hutter for assistance with administering the protocol and managing [Asc]serum samples, Tonya White for assistance with choosing landmarks and setting the protocol for repeatable positioning of VOI, our subjects for their willingness to participate and for cooperation, Ivan Tkac for MRS-related advice throughout the project, and colleagues at CMRR for maintaining spectrometer performance, as well as for accommodating our usage of the scanner for this protocol. The National Institutes of Health (R21-AG029582; P41-RR008079; P30-NS057091; M01-RR00400) provided financial support.

Abbreviations used

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- Asc

ascorbate

- [Asc]brain

brain ascorbate concentration

- [Asc]serum

blood serum ascorbate concentration

- CI

confidence interval

- CMRR

Center for Magnetic Resonance Research

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- GCRC

General Clinical Research Center

- GSH

glutathione

- [GSH]brain

bran glutathione concentration

- IV

intravenous

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- REE

resting basal energy expenditure

- RF

radiofrequency

- SVCT2

sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter

- VOI

volume of interest

References

- 1.Esposito E, Rotilio D, Di Matteo V, Di Giuliio C, Cacchio M, Algeri S. A review of specific dietary antioxidants and the effects of biochemical mechanisms related to neurodegenerative processes. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:719–735. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casetta I, Govoni V, Granieri E. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2033–2052. doi: 10.2174/1381612054065729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnen JA, Breitner JC, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR, Quinn JF, Montine TJ. Free radical-mediated damage to brain in Alzheimer’s disease and its transgenic mouse models. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Section 10.5.11. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. Antioxidants, epidemiology and neuro-degenerative disease; pp. 645–646. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson HJ, Heimendinger J, Sedlacek S, Haegele A, Diker A, O’Neill C, Meinecke B, Wolfe P, Zhu Z, Jiang W. 8-Isoprostane F2α excretion is reduced in women by increased vegetable and fruit intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:768–776. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terpstra M, Marjanska M, Henry P-G, Tkac I, Gruetter R. Detection of an antioxidant profile in the human brain in vivo via double editing with MEGA-PRESS. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1192–1199. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terpstra M, Henry P-G, Gruetter R. Measurement of reduced glutathione (GSH) in human brain using LCModel analysis of difference-edited spectra. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:19–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terpstra M, Vaughan TJ, Ugurbil K, Lim KO, Schulz SC, Gruetter R. Validation of glutathione quantitation from STEAM spectra against edited 1H NMR spectroscopy at 4T: application to schizophrenia. Magma. 2005;18:276–282. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terpstra M, Gruetter R. 1H NMR detection of vitamin C in human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:225–229. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terpstra M, Tkac I, Rao R, Gruetter R. Quantification of vitamin C in the rat brain in vivo using short echo time 1H MRS. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:979–983. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emir U, Deelchand D, Henry P-G, Terpstra M. Simultaneous quantitation of T2 and concentration of ascorbate and glutathione in the human brain from the same double edited spectra. NMR Biomed. 2010 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1583. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice ME, Russo-Menna I. Differential compartmentalization of brain ascorbate and glutathione between neurons and glia. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob RA. The integrated antioxidant system. Nutr Res. 1995;15:755–766. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heideger MA. New view at C. Nat Med. 2002;8:445–446. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, May JM. Ascorbic acid spares alpha-tocopherol and prevents lipid peroxidation in cultured H4IIE liver cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;247:171–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1024167731074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitazawa M, Podda M, Thiele J, Traber M, Iwasaki K, Sakamoto K, Packer L. Interactions between vitamin E homologues and ascorbate free radicals in murine skin homogenates irradiated with ultraviolet light. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;65:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison FE, May JM. Vitamin C function in the brain: vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium and Carotenoids. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; Washington DC: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallner A, Hartmann D, Hornig D. Steady-state turnover and body pool of ascorbic acid in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:530–539. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Kalz A, Wesley RA, Levine M. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:533–537. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riordan HD, Hunninghake RB, Riordan NH, Jackson JJ, Meng X, Taylor P, Casciari JJ, Gonzales MJ, Miranda-Massari JR, Mora EM, Rosario N, Rivera A. Intravenous ascorbic acid: protocol for its application and use. PR Health Sci J. 2003;22:287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terpstra M, Andersen PM, Gruetter R. Localized eddy current compensation using quantitative field mapping. J Magn Reson. 1998;131:139–143. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adriany G, Gruetter R. A half-volume coil for efficient proton decoupling in humans at 4 Tesla. J Magn Reson. 1997;125:178–184. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czosnyka M, Czosnyka Z, Momjian S, Picakrd JD. Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Physiol Meas. 2004;25:R51–R76. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/5/r01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruetter R, Tkac I. Field mapping without reference scan using asymmetric echo-planar techniques. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:319–323. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200002)43:2<319::aid-mrm22>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tkac I, Starcuk Z, Choi I, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1ms echo time. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:649–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<649::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mescher M, Merkle H, Kirsch J, Garwood M, Gruetter R. Simultaneous in vivo spectral editing and water suppression. NMR Biomed. 1998;11:266–272. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199810)11:6<266::aid-nbm530>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:260–264. doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Govindaraju G, Young K, Maudsley A. Proton, NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13:129–153. doi: 10.1002/1099-1492(200005)13:3<129::aid-nbm619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry P, Marjanska M, Walls J, Valette J, Gruetter R, Ugurbil K. Proton-observed carbon-edited NMR spectroscopy in strongly coupled second-order spin systems. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:250–257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soher BJ, Pattany PM, Matson GB, Maudsley A. Observation of coupled 1H metabolite resonances at long TE. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1283–1287. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi C, Coupland NJ, Bhardwaj PP, Kalra S, Casault CA, Reid K, Allen PS. T2 measurement and quantification of glutamate in human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:971–977. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice ME. Ascorbate regulation and its neuroprotective role in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spector R, Johanson C. Micronutrient and urate transport in choroid plexus and kidney: implications for drug therapy. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2515–2524. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Yamamoto F, Gondo S, Yanase T, Mukai T, Maeda M. 6-Deoxy-6[131I]iodo-L-ascorbic acid for the in vivo study of ascorbate: autoradiography, biodistribution in normal and hypolipidemic rats, and in tumor-bearing nude mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1906–1911. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukaguchi H, Tokui T, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Chen X-Z, Wang Y, Brubaker RF, Hediger MA. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature. 1999;399:70–75. doi: 10.1038/19986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spector R. Nutrient transport systems in brain: 40 years of progress. J Neurochem. 2009;111:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tveden-Nyborg P, Johansen LK, Riada Z, Villumsen CK, Larsen JO, Lykkesfeldt J. Vitamin C deficiency in early postnatal life impairs spatial memory and reduces the number of hippocampal neurons in guinea pigs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:540–546. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, Welch RW, Washko PW, Dhariwal KR, Park JB, Lazarev A, Graumlich JF, King J, Cantilena LR. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiber H, Ruff M, Uhr M. Ascorbate concentration in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum. Intrathecal accumulation and CSF flow rate. Clin Chim Acta. 1993;217:163–173. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(93)90162-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serot J-M, Bene M-C, Faure GC. Choroid plexus, ageing of the brain, and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Biosci. 2003;8:S515–S521. doi: 10.2741/1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sotiriou S, Gispert S, Cheng J, Wang Y, Chen A, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Miller GF, Kwon O, Levine M, Guttentag SH, Nussbaum RL. Ascorbic-acid transporter Slc23a1 is essential for vitamin C transport into the brain and for perinatal survival. Nat Med. 2002;8:514–517. doi: 10.1038/0502-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrison FE, Hosseini AH, McDonald MP, May JM. Vitamin C reduces spatial learning deficits in middle-aged and very old APP/PSEN1 transgenic and wild-type mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qui S, Li L, Weeber EJ, May JM. Ascorbate transport by primary cultured neurons and its role in neuronal function and protection against excitotoxicity. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1046–1056. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison FE, Yu SS, Van Den Bossche KL, Li L, May JM, McDonald MP. Elevated oxidative stress and sensorimotor deficits but normal cognition in mice that cannot synthesize ascorbic acid. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1198–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai Q, Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Jackson JC, Larson EB. Fruit and vegetable juices and Alzheimer’s disease: the Kame project. Am J Med. 2006;119:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rengachary SS, Ellenbogen RS, editors. Principles of Neurosurgery. Elsevier Mosby; Edinburgh: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hrabetova S, Nicholson C. Contribution of dead-space microdomains to tortuosity of brain extracellular space. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flaring UB, Hebert C, Wernerman J, Hammarqvist F, Rooyackers OE. Circulating and muscle glutathione turnover in human endotoxaemia. Clin Sci. 2009;117:313–319. doi: 10.1042/CS20080462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kyparos A, Vrabas IS, Nikolaidis MG, Riganas CS, Kouretas D. Increased oxidative stress blood markers in well-trained rowers following two thousand-meter rowing ergometer race. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:1418–1426. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a3cb97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elverfeldt DV, Buechert M, Kaufmann R, Huell M, Hennig J. Evidence for detection of ascorbic acid in the human brain at 3T. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting ISMRM; Seattle, WA, USA. 2006. p. 3145. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shih Y, Buchert M, Chung H, Hennig J, von Elverfeldt D. Vitamin C estimation with standard 1H spectroscopy using a clinical 3T MR system: detectability and reliability within the human brain. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:351–358. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tkac I, Oz G, Adriany G, Ugurbil K, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the human brain at high magnetic fields: metabolite quantification at 4T vs 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:868–879. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terpstra M, Ugurbil K, Tkac I. Noninvasive quantification of human brain ascorbate concentration using 1H NMR spectroscopy at 7 T. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:227–232. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gambarota G, Mekle R, Xin L, Hergt M, van der Zwaag W, Krueger G, Gruetter R. In vivo measurement of glycine with short echo-time 1H MRS in human brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Mater Phys. 2009;22:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the onlineversion of this article:

Fig. S1. [Asc]brain and [GSH]brain time courses for each individual subject (shams, S1–S2 and treated probands P1–P10, sham and proband studies S2 ans P2 were both completed by the same person). The error bars are the Cramer Rao Lower Bounds from LCModel. Two scans were not completed because of a power outage. The three symbols denote data points for which overall motion (i.e. the sum over all three axes of the absolute value of how much the subject moved during the scan session) was minor (open diamonds for ≤ 3 mm), moderate (filled diamonds for 4–6 mm) and marked (circled diamonds for 7–9 mm).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.