Abstract

Culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions are needed to reduce the risk of DUI recidivism among diverse populations. Using core elements of Motivational Interviewing, we developed a culturally-relevant web-MI intervention (web-MI) in English and Spanish to serve as a standalone or adjunctive program in DUI educational settings and evaluated its feasibility and acceptability among clients with first-time DUI offenses. We conducted an iterative formative assessment using focus groups with staff (n = 8) and clients (n = 27), and usability interviews with clients (n = 21). Adapting MI for the web was widely accepted by staff and clients. Clients stated the web-MI was engaging, interactive and personal, and felt more comfortable than past classes and programs. Spanish-speaking clients felt less shame, embarrassment, and discomfort with the web-MI compared to other in-person groups. Results support the viability of web-MI for DUI clients at risk for recidivism and highlight the importance of adapting the intervention for diverse populations. Key decisions used to develop the web-MI are discussed.

Keywords: Brief intervention, computer and web intervention, Motivational Interviewing, DUI

1. Introduction

Alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents are a significant public health concern. Alcohol accounts for approximately one-third of the nation’s fatal crashes (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2008); for every death, 45 survivors require Emergency Department care (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2000). In most states, people who receive a first-time driving under the influence (DUI) offense are required to complete an alcohol education/counseling program (AEP); however, AEPs have shown only minimal results on reducing alcoholism and associated motor vehicle accidents (Daoud & Tashima, 2007; Wells-Parker & Williams, 2002). More than one-third of all DUI convictions are clients with repeat offenses, and a disproportionate number of DUI fatalities are caused by drivers previously convicted of an alcohol-related accident (Christophersen, Skurtveit, Grung, & Morland, 2002; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2005). These statistics underscore a need to increase access to effective care for clients with a first-time DUI offense to decrease recidivism.

When designing interventions appropriate for diverse groups, it is important to ensure the cultural and linguistic context is relevant for all groups, while also staying true to the fidelity of the original intervention (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). Interventions developed for predominantly White samples cannot be assumed to be generalizable and equally effective in other populations (Marín et al., 1994) because studies often exclude less acculturated, low income, and less literate non-English speaking populations (Humphreys & Weisner, 2000; Miller, Villanueva, Tonigan, & Cuzmar, 2009). Even linguistic translation using well-accepted methods does not guarantee the cultural appropriateness of an intervention (Weidmer, Brown, & Garcia, 1999) because literal translation does not always incorporate cultural meanings that cannot be dissociated from language (Castro et al., 2004). The lack of cultural appropriateness of interventions could lead to differential efficacy if the intervention fails to convey the intended message across cultures (Chapman & Carter, 1979). Thus, when developing interventions, the content should be accessible and relevant to diverse groups.

Incorporating cultural concerns into interventions is important when there may be subgroup differences in engagement (e.g., rates of treatment access, utilization, and completion), intervention mediators, and intervention outcomes (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Lau, 2006). For example, including cultural concerns, such as how drinking may affect the family, may be important for Latino individuals with core values to respect and be loyal to their family (Sue & Sue, 1999).

In California, Latinos are disproportionately more likely to be arrested for a DUI compared to other race/ethnicities, have higher rates of recidivism, and are more likely to die in alcohol-related crashes than their White counterparts (Hunter, Wong, Beighley, & Morral, 2006). In Los Angeles, Latinos represent 48% of the city’s population (U.S. Census Bureau., 2009) and comprise 58% of the DUI population. Those who receive a DUI must attend an alcohol education program to satisfy their sanctions; thus, the AEP represents a valuable and unique opportunity for outreach to Latinos and to provide culturally sensitive services to help curb future recidivism.

One well-studied counseling approach particularly suited for AEPs is Motivational Interviewing (MI), in which a counselor uses a non-confrontational and non-judgmental style to resolve a client’s ambivalence to changing their behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2007). This approach may be particularly helpful for individuals who have received a first-time DUI offense because the DUI event often increases an individual’s readiness to change their drinking behavior (Wells-Parker, Kenne, Spratke, & Williams, 2000) and an explorative approach such as MI may help elicit this change.

MI emphasizes collaboration between client and counselor by avoiding persuasion and promoting partnership through idea sharing; evocation by eliciting the client’s ideas about change and being accepting of where the client is at in regard to his/her drinking; and client autonomy/support, which involves leaving the decision to change up to the client and supporting them in their change process (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2010). Clinicians can use MI to deliver education and skill building, strategies often used by AEPs; thus incorporating MI into this setting is an easy way to help clients work more effectively toward making changes.

The effectiveness of brief in-person MI interventions on drinking outcomes, such as heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences is well established, and this approach has shown promise in Latino populations (Arroyo, Miller, & Tonigan, 2003; Carroll et al., 2009; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005). Few studies, however, have examined MI’s effectiveness with DUI clients who are mandated to treatment (Wells-Parker & Williams, 2002) and no studies to our knowledge have evaluated MI with Latino clients with DUI offenses.

The widespread use of in-person MI for DUI offenses is often limited by the availability of bilingual counselors, the cost to learn MI, and the difficulty of implementing the intervention uniformly and reliably. Interventions that merge MI with interactive technology (web-MI) may be an efficient and innovative way to address some of these issues because web-MIs can be disseminated to new settings, populations, and areas that might not otherwise have the capacity for in-person evidence-based care. Most community settings lack the resources to provide training in evidence-based care, and practical issues such as staff turnover can make it challenging to implement evidence-based care with fidelity. Web-MIs can address these issues because the content is programmable and automated, which may be particularly important when disseminating MI in diverse populations and in different languages.

Web-MIs are also less expensive than one-on-one treatment, offer easy access, and the anonymity overcomes the stigma sometimes associated with formal treatment (Kypri, Saunders, & Gallagher, 2003; Saitz et al., 2004; Walker, Roffman, Picciano, & Stephens, 2007); this may be especially important for Latinos with low acculturation, as they may be less likely to discuss alcohol issues in-person due to distrust or fear (Miranda, Estrada, & Firpo-Jimenez, 2000). In addition, simple interactive exercises may reduce barriers related to low literacy where reading and computer experience is limited. Several studies have successfully used computer programs with Latinos who had minimal literacy and computer experience. For example, Anger and colleagues developed computer-based trainings with Latino immigrants and found that individuals with three or more years of education found the trainings easy to understand (Anger, Tamulinas, Uribe, & Ayala, 2004) and helpful in learning about job safety (Anger et al., 2006). Leeman-Castillo and colleagues developed computer kiosk programs in English and Spanish to promote cardiovascular health and found improvements in nutrition and physical activity two months later (Leeman-Castillo, Beaty, Raghunath, Steiner, & Bull, 2010). A third of these patients did not complete high school. These studies provide some evidence that computer programs can be helpful even with individuals who have low literacy.

Web-based interventions for substance use have been evaluated with positive effects demonstrated for alcohol, nicotine, and other drug use (Copeland & Martin, 2004; Khadjesari, Murray, Hewitt, Hartley, & Godfrey, 2011); however, few of these web-based studies incorporated MI or targeted a multicultural population. A recent review (Khadjesari et al., 2011) identified 24 web intervention studies for drinking from 1997–2008; most targeted students (n = 18) and three targeted adult problem drinkers from the general population. In all these studies, participants were typically White (75–100%), with the exception of two studies (54% White and 30% White), and only five studies utilized MI as part of the intervention. Examples of web-MIs include the Drinker’s Check-Up for at-risk drinkers in the general population and military (Hester, Squires, & Delaney, 2005; Pemberton et al., 2011), an international smoking cessation intervention targeting English and Spanish-speakers (Muñoz et al., 2009), and a drug use intervention for postpartum women (Ondersma, Svikis, & Schuster, 2007). We know of no web-MI interventions, however, specifically intended for drinkers with a first-time DUI offense that have used culturally appropriate methods for both English and Spanish-speaking populations.

Furthermore, little research has evaluated the comparative effectiveness of in-person and web-MI. Most studies comparing modality have used interventions with different content and intensity (in-person MI vs. a computerized educational web intervention), making it difficult to discern if intervention effects are attributable to the content or the modality (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Carey, Carey, Henson, Maisto, & DeMartini, 2011). Because web-MI interventions solve problems associated with in-person interventions (e.g., expense and uniform implementation), research is needed to understand whether mode of delivery affects outcomes.

We developed our web-MI intervention in response to a growing need for alcohol education programs and specifically tailored our web-MI to diverse ethnic groups. The intervention’s innovations include: (1) making it appropriate for clients with a first-time DUI offense who have at-risk drinking and therefore are at increased likelihood of recidivism; (2) incorporating dynamic, collaborative, and interactive MI strategies traditionally provided by in-person counselors; and (3) making it culturally and linguistically acceptable for low-income, low-literacy English- and Spanish-speaking individuals who are predominantly Latino.

This paper describes our iterative formative assessment to develop an interactive web-MI intervention for English- and Spanish-speaking clients who had a first-time DUI offense and to test its feasibility and usability in this population. We conducted focus groups with DUI program staff and clients, and individual beta-testing interviews with clients to assess the acceptability and feasibility of the web-MI. This work is part of an ongoing study called Project REACH (REthinking Avenues for CHange; in Spanish, REtomondo Avenidas para el Cambio Hoy), a randomized controlled study that compares our web-MI to in-person MI for clients who have a first-time DUI offense (Watkins RC1AA019034). RAND’s internal review board approved all protocols and procedures. Documenting the formative assessment process is important to demonstrate the intervention’s feasibility and acceptability to both Spanish and English-speakers and to document the methods used to promote cultural and linguistic equivalence. Results from the efficacy study will be reported separately.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 8 AEP staff (5 counselors and 3 intake workers) and 48 (33 English-speaking, 15 Spanish-speaking) clients attending the AEP for a first-time DUI offense participated in the study. Staff were invited by DUI administrators to volunteer for one focus group because of their direct interaction with DUI clients. Clients were adults 18 and older who were enrolled in a 3-, 6-, or 9-month program at the AEP. Clients participated in either focus groups or usability testing; a more detailed sample description is located below.

2.2. Measures

The focus group protocol had two main sections: (1) the acceptability and feasibility of the in-person feedback sheet for a DUI population (e.g., Which messages were the most convincing to reduce drinking while driving? Least convincing? What was the most helpful information that you saw? Least helpful? What do you think would help other clients participate in this program?); and (2) the cultural acceptability of the intervention content (e.g., How can we make the program helpful to people from different backgrounds? What messages, images, or phrases are most meaningful, within and across cultures?).

The usability testing interviews were conducted in two ways to receive different types of feedback. The first method was through live narration where a research assistant sat next to the client and asked him/her to narrate or state aloud their comments about each screen of the web-MI (e.g., “Without pressing anything yet, please describe the options you see on this first page. What would you press first?”). This process allowed us to identify buttons that might be misplaced, as well as potentially confusing language and misleading instructions. The second method consisted of the client reviewing the program in its entirety and then being interviewed afterwards (e.g., “What did you think of the program?” and “What was most helpful/unhelpful?”). We also assessed what changes they would suggest for the web-MI and how it differed from other alcohol-related programs they had attended. Half of the participants (n = 10) did the first and second testing method, and the remaining half (n = 11) only did the second method.

2.3. Setting

Project REACH is conducted in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Alcohol and Drug Program Administration (ADPA) and three private AEPs under ADPA’s regulatory authority. In Los Angeles County, when an adult is arrested for DUI for the first time, in addition to a suspended driver’s license and other sanctions, the adult must also attend a 3-, 6-, or 9-month AEP that provides weekly educational classes and group sessions that review and discuss the physiological effects of alcohol and drugs, assertive communication, alcohol as a disease, family relationship skills, problem solving, abstinence, domestic violence, and relapse prevention.

Two of the DUI programs provide English and Spanish-speaking services to predominantly lower income clientele, and the third program provides bilingual services to a slightly higher income neighborhood. Each of these sites serves predominantly Latino clients.

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Overview

The Project REACH web-MI intervention evolved out of our previous research to develop brief, in-person MI interventions targeting the drinking behavior of English-speaking teens and adults. These interventions provided personalized feedback about drinking, expectancies and consequences, and also included MI components (e.g., confidence rulers) and other exercises that have been adapted for MI (e.g., willingness rulers and decisional balance). Studies using these components have showed that in-person MI interventions reduced alcohol, drug use, and associated consequences (D’Amico & Edelen, 2007; D’Amico, Miles, Stern, & Meredith, 2008; Osilla et al., 2010; Osilla, Zellmer, Larimer, Neighbors, & Marlatt, 2008).

Our intervention development team consisted of researchers and clinicians with expertise in MI, web-based interventions, and Spanish and Latino health literacy. One of the team members has expertise developing English and Spanish web-MIs for smoking (Muñoz et al., 2009). Two of the team members are clinical psychologists affiliated with the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) who have developed several MI interventions for different populations (D’Amico et al., 2008; D’Amico, Osilla, & Hunter, 2010; D’Amico et al., in press; Osilla et al., 2008). MINT affiliation requires the completion of a two-day workshop designed to teach the training methods, techniques, and spirit of the MI approach. Our goal was to develop a web-MI in English and Spanish that was appropriate and culturally relevant for both Latinos and non-Latinos. While we expected content to be the same for both English and Spanish-speakers and Latinos and non-Latinos, we wanted to be sure that presentation of the content was culturally relevant and would therefore reach diverse populations. To accomplish this, we first modified the content for our in-person MI interventions for use with a DUI population, creating a version in both English and Spanish. Next, we conducted focus groups to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the in-person MI intervention for DUI clients and to assess how to adapt the intervention delivery for the web in both languages. These strategies are consistent with developing interventions in a culturally-sensitive manner (Castro et al., 2004; Hall, 2001).

We utilized the focus group feedback from the in-person MI intervention to create the web-MI version, simultaneously developing it in English and Spanish, and integrating MI strategies traditionally provided by a counselor (e.g., collaboration, autonomy). Lastly, English and Spanish-speaking DUI clients tested our web-MI intervention for usability/acceptability and provided us feedback during individual interviews, which we used to iteratively edit the web-MI intervention. Each step is described in more detail in the following sections.

2.4.2. Modification made to our original in-person MI interventions to target a DUI population and Spanish speakers

We drew from our previous in-person brief interventions for English-speaking teens and adults and adapted the personalized feedback sheet for a DUI population by including consequences related to DUI (e.g., accidents and legal consequences), information about blood alcohol content (BAC), and strategies for avoiding future DUIs.

For content previously developed only in English (intervention manual and feedback sheet), we had a bilingual researcher, who was a native Spanish speaker and had experience with the subject matter and the target population, conduct the forward translation into Spanish. To inform the translation process, the research team started by reviewing existing Spanish in-person MI interventions, educational content, and alcohol language from validated instruments (Diez-Quevedo, Rangil, Sanchez-Planell, Kroenke, & Spitzer, 2001; Gandek et al., 1998; Hernandez et al., 2006; Saitz, Horton, Sullivan, Moskowitz, & Samet, 2003; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fuente, & Grant, 1993; Sobell et al., 2001; Wulsin, Somoza, & Heck, 2002). Another native Spanish speaker who was also bilingual then conducted a back translation, and a committee composed of bilingual researchers and field staff reviewed and identified discrepancies to reach consensus on the language equivalence (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, & Ferraz, 2000).

For new in-person intervention content, we used a parallel process of development (Rogers, Lin, & Rinaldi, 2011; Solano-Flores, Trumbull, & Nelson-Barber, 2002), in which bilingual and bicultural researchers developed material simultaneously in English and Spanish so that the language and cultural content would be equivalent and at a lower level of literacy. In this way, the words in English or Spanish were chosen to carry the same intended meaning in both languages without being constrained by using either language as the “gold standard.” Spanish content used “broadcast” or standard Spanish language. Examples of cultural adaptations of the intervention include translating idiomatic expressions (e.g., getting high or feeling drunk) and intervention key terms (e.g., BAC, DUI) in Spanish, providing examples of how drinking can affect the family, choosing the neutral name “Danny” to illustrate the balanced placebo design example, and using low literacy methods to convey messages (e.g., using a thermometer to convey how BAC impairment increases as BAC values increase; using beer bottles to illustrate normative feedback for number of drinks).

2.4.3. Conduct staff and client focus groups to assess feasibility/acceptability of the in-person MI intervention for DUI clients

We conducted one staff focus group. A DUI administrator identified all counselors and intake workers, who were then invited to participate in the focus group. Staff spoke from their professional capacity conducting classes and/or intakes in English and Spanish. Staff were not paid and verbally consented to participate.

We conducted two focus groups with English-speaking clients (n = 9, 11) and two with Spanish-speaking clients (n = 2, 5). Over the course of a month, we recruited clients at the beginning of DUI classes by giving them a consent-to-contact form. RAND called clients who consented and scheduled an in-person appointment to conduct informed consent procedures. All clients were enrolled in one of the three DUI programs. Clients provided informed consent and were paid $25 for their participation. Client focus groups were led by a clinical psychologist (K.O.) in English or a physician (M.L.) in Spanish. A bilingual co-facilitator was also present and took extensive notes. All groups were audio taped, lasted about two hours, and followed a written protocol of open-ended questions.

2.4.4. Adapt the in-person DUI intervention to a web format (web-MI) in both languages

Using feedback from the focus groups, we adapted the in-person intervention content to a 45-minute web-MI session that clients could test. The web-MI was designed so that feedback would be tailored to the client’s baseline survey about drinking behavior and perceptions and to their live responses while engaging in the program (e.g., if they clicked they were “surprised,” a video would pop up in the next screen tailored to that response). After clients completed an online baseline survey, survey responses populated the web-MI content. This content included personalized feedback on: (1) how their drinking and guesses of others’ drinking compared to other men/women their age in the U.S. (Chan, Neighbors, Gilson, Larimer, & Marlatt, 2007); (2) their positive beliefs about drinking and the balanced placebo design experiment, which describes how positive beliefs about alcohol can affect behavior (Marlatt & Rohsenow, 1980); (3) their negative consequences from drinking, including their estimated blood alcohol content value; and (4) strategies for avoiding consequences in the future. In addition, clients who scored 10 or more on their baseline Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), indicating moderate depression (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001), also received information on the biphasic response to alcohol.

We developed the web-MI simultaneously in Spanish and English in order to create an intervention with Spanish and English forms culturally equivalent in content, language, and literacy. We also collaborated with computer programmers and instructional technicians with expertise in programming interactive web programs to make the design of the program simple, clear, engaging, and easy to understand (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of Adapting In-Person MI for the Web

| MI Intervention Content | Web-MI Adaptation |

|---|---|

| Section 1: Introduction | |

| Intervention Philosophy |

|

|

| |

| Section 2: My Patterns | |

| Normative Feedback |

|

| Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) |

|

|

| |

| Section 3: My Beliefs | |

| Decisional Balance |

|

| Balanced Placebo Design |

|

| Biphasic Response to Alcoholb |

|

|

| |

| Section 4: Consequences | |

| Negative Consequences |

|

| Strategies |

|

|

| |

| Section 5: Next Steps | |

| Confidence and Willingness Rulers |

|

| One Thing I Learned Today |

|

| Conclusion |

|

Chan et al., 2007

For clients with moderate depression that scored 10 and higher on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Chan et al., 2007; Kroenke et al., 2001)

2.4.5. Conduct client usability testing interviews

Over the course of 4 months, we recruited 24 clients who had a first-time DUI offense. Due to poor internet activity at the DUI site, three clients were unable to complete the usability testing and excluded from analyses, resulting in a total of 21 clients (13 English, 8 monolingual Spanish-speaking) who completed usability testing, which is a sufficient number of interviews to identify the most important themes (Bernard & Ryan, 2009; Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006; Morgan, Fischoff, Bostrom, & Atman, 2002; Nielsen, 2000).

The mean age of the clients was 28.1 years old (SD = 6.6) and 76% were male. Of the 13 English-speaking clients, 10 were Latino; 11 were born in the United States and 2 were born in Mexico. All participants reported using the internet daily. Of the 8 monolingual Spanish-speaking clients, we had birth origin data for 6; 2 were born in the United States and 4 were born in Mexico. Three of the eight Spanish speakers had minimal internet usage (less than once a week), and one was not asked about his internet usage. While most participants were Latino, those who were bilingual chose to do the intervention in English instead of Spanish (and those who were monolingual chose the Spanish version).

We conducted two rounds of usability testing for each language. We recruited new and existing clients enrolled in the DUI programs through consent-to-contact procedures so that we could have a diverse sample.

During usability testing, research assistants interviewed clients using a written protocol of open-ended questions to assess their experience while clients were using and interacting with the web-MI. Questions addressed how clients navigated the system (e.g., please describe the options you see on this first page and what you think the buttons do; if you were exploring, what would you click on first?), client’s experiences completing exercises (e.g., what do you think is the purpose of this page?), and their impressions of the program (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2010a, 2010b). The usability testing was conducted with two rounds of different clients such that revisions could be made after the first round and then subsequently tested in the next round. For the purposes of this paper, we summarize together themes from both rounds of interviews.

2.5. Qualitative Data Analyses

After the completion of the focus groups and usability interviews, the first and third authors independently reviewed audiotapes, transcripts, and notes. Spanish focus groups were translated to English. The purpose of this review was to identify, label, and group together key points that spoke to the acceptability of the web-MI. Following grounded theory analyses (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), key points with similar themes were grouped together into a category if said several times (e.g., web-MI made me think about my drinking; Ryan & Bernard, 2003). The first and third authors then discussed each of the categories and generated underlying themes from the data (e.g., web-MI was interactive and felt personal). After themes were extracted, classic content analysis was used to identify quotes that fit each of the themes (Krippendorf, 1980; Weber, 1990). Each author independently sorted quotes by theme and then together reached a consensus on any discrepancies. Themes were aggregated by language and then aggregated to assess client feedback to the web-MI program.

3. Results

3.1. Staff and Client Focus Groups Themes

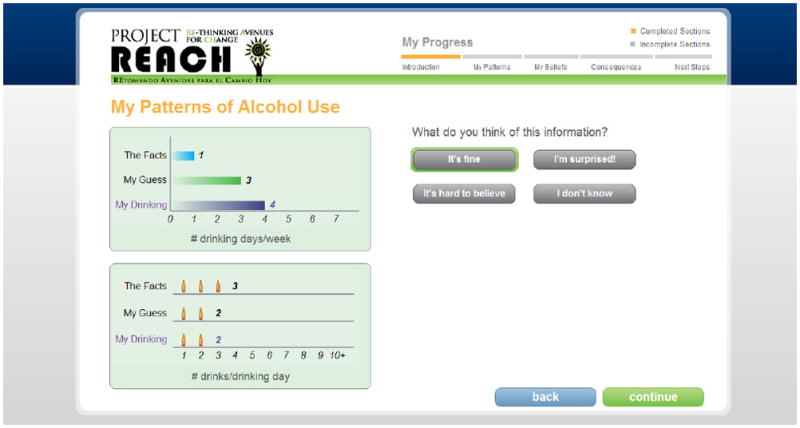

Table 2 summarizes underlying themes that emerged from staff and client focus groups. Focus group feedback informed the content and layout of our web-MI intervention. Staff and client feedback reinforced our plans to use MI-consistent language and to integrate exercises to actively engage client participation. Clients in the Spanish focus group stated it was important to feel comfortable talking without feeling shame or being judged. Both English and Spanish groups felt that financial punishments and discussing DUI consequences (e.g., death, accidents) affected them in the AEP program. Staff and clients suggested that in order to make the organization of information clearer, each topic should have its own screen and there should be a systematic design for each screen. We also simplified our charts by using pictures and simple labels such as “The Facts,” “My Guess,” “My Drinking” (see Figure 1), and deemphasized reading by using video and audio technology. We added additional positive beliefs and negative consequences that were culturally relevant to our baseline survey questions, but also allowed clients to type in their own responses. For example, we added consequences about not meeting family responsibilities or disappointing family and/or children based on feedback from Latino clients.

Table 2.

Staff and Client Focus Group Themes

| Focus Group Section | Staff/Counselors | Clients |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability and Feasibility |

|

|

| Comments about the Feedback sheet |

|

|

| Cultural considerations |

|

|

Figure 1.

Web-MI screenshot depicting client’s reaction to normative feedback

3.2. Web-MI Development and Client Feedback

To integrate MI into our web intervention, we used videos, audios, and artificial intelligence to convey core elements of in-person MI captured by the Motivational Interviewing Integrity Scale (MITI; Moyers et al., 2010), such as evocation, collaboration, empathy, and autonomy/support. First, we included open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective statements, and summaries, which framed user’s responses in MI language so that the intervention would feel collaborative and supportive of the client. Clients were invited to respond to questions (e.g., “What do you think of this information?” followed by multiple choice answers such as “It’s fine,” “I’m surprised,” “It’s hard to believe”) and a personalized video message appeared that was tailored to their response (e.g., if they clicked “I’m surprised”, a video conveyed how surprise is common and emphasized the importance of personal choice in using the information). Second, to increase evocation, we strategically asked clients to type in responses to elicit change talk (e.g., for the confidence rulers, why a 4 and not a 0?). Finally, to emphasize autonomy, we introduced the program by saying that any changes in drinking and driving behavior would be their decision. This strategy was also carried out throughout the program and the videos. Thus, the program did not force clients to choose a change strategy if they were not ready.

Table 3 summarizes underlying themes and respective quotes that emerged from the client web-MI usability interviews, which we categorized by key MI components (i.e., evocation, collaboration, and autonomy). Major themes included:

Table 3.

Web-MI Usability Feedback From English and Spanish Participants

| MI component | English | Spanish |

|---|---|---|

| Evocation: Web-MI engaged them in the change process |

|

|

| Collaboration and Empathy: Web-MI was interactive and felt personal |

|

|

| Autonomy/Support: Different from other classes/programs |

|

|

| Web-MI was simple and helpful |

|

|

| Things to change |

|

|

Evocation

Several clients felt the web-MI was evocative because it engaged them and encouraged them to think about things in a new way. Both English and Spanish-speaking clients consistently commented that the information was helpful, new, and meaningful to them. For example, many were surprised by the normative feedback and how their drinking compared to their peers and some commented that this information helped them to understand their drinking more.

Collaboration

Clients felt the web-MI was collaborative and personalized. Clients stated they were asked to share their thoughts and opinions, and they felt the web-MI was tailored to their responses.

Autonomy/Support

Clients also felt supported by the web-MI. Clients stated the program was different from other alcohol-related classes or programs because it was individualized. They also said they would be more comfortable with the web-MI intervention compared to an in-person class because there was less shame and embarrassment. This theme was more common among the Spanish clients. More Spanish-speaking clients commented on the non-judgmental nature of the web-MI program: “A lot of people are really afraid to either tell their problems or to accept them [in groups]…[with the web-MI] it’s just you and the screen.” Another client stated: “A lot of people have a problem communicating their problems, talking in person with a doctor, or somebody else, so if you are in front of the computer you are given that information but at the same time you are not feeling [bad].” Several Spanish clients said that interacting with the web-MI and typing in their responses was more comfortable than sharing in a group.

Other web-MI feedback

Clients also felt the web-MI was simple and helpful. This theme was important because some of the clients were of low literacy and had minimal computer experience. Clients thought the program was easy to navigate. Clients (n = 4) also provided feedback on the biphasic response to alcohol. One client stated he valued the information and could see how alcohol affected his mood over time. Another client thought the information was easy to follow. Finally, when asked about things we could add or change to the web-MI, English and Spanish clients consistently reported that we should add more negative consequences from drinking to our materials. Examples of these suggestions included adding statistics about the number of deaths and car accidents each year, describing the negative physical consequences from drinking, and relating stories about how families and relationships can suffer from drinking. To maintain consistency with the non-judgmental approach of MI, we opted to not include “scare tactics” and statistics related to alcohol-related negative consequences, but included other individual-level alcohol-related consequences from the Short Inventory of Problems instrument (e.g., I have had money problems because of my drinking; Miller et al., 1995).

4. Discussion

The current study addressed some limitations of previous research by utilizing linguistically and culturally appropriate methods to create a web-MI intervention that was feasible, acceptable, and equivalent for both English and Spanish-speaking clients mandated to DUI treatment. Strengths of our formative assessment process included our decision to simultaneously develop the web-MI in Spanish and English. This decision was important because interventions translated and culturally adapted “after the fact” may encounter problems with translation and cultural equivalence, which may ultimately impact overall effectiveness (Rogers et al., 2011; Solano-Flores et al., 2002).

Furthermore, our intervention extended the capacity of existing web-MI interventions by using interactive exercises, videos, and audios to engage the client. Importantly, clients noticed these differences as they found the web-MI evocative, collaborative, and autonomy-driven. We observed three differences between English and Spanish-speaking clients. First, Spanish monolingual clients were of slightly lower literacy and tended to use the internet minimally. Second, Spanish-monolingual clients recommended that the intervention emphasize more beliefs and consequences associated with family and friends (e.g., drinking problems affect the whole family). Third, Spanish-monolingual clients reported feeling less embarrassment, shame, and discomfort with the web-MI compared to English-speaking clients. The discomfort that Spanish-speaking clients reported with existing in-person programs could be due, in part, to concern about others’ opinions and “machismo.” For example, most alcohol-related programs for Spanish-speaking individuals can be more confrontational in nature. Thus, traditional programs that assert authority or “machismo” are typically not conducive to change (Hoffman, 1994). Research suggests that for both Whites and non-Whites (including Latinos), confrontational styles are not as effective when compared to less confrontational styles among individuals with problem drinking (Miller, Benefield, & Tonigan, 1993; White & Miller, 2007). In addition, MI may be a culturally appropriate approach for Latinos because the emphasis is on client autonomy, empowerment, and responsibility (Feldstein Ewing, 2010).

One surprising finding from our focus groups was that staff and clients both recommended integrating more negative consequences from alcohol use and DUI into the web-MI. This is interesting because existing research shows that scare tactics, education, and punishment alone do not create behavioral change (e.g., Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994; West & O’Neal, 2004), especially among individuals who drink and drive (Yu, Evans, & Clark, 2006). We hypothesize that staff and clients may have been reflecting on the differences between their alcohol education classes and the web-MI. For example, it is common for DUI programs to educate clients on the rates of DUI-related car accidents and the effects of alcohol on the liver. Future versions of the web-MI may explore how to integrate these types of facts in a MI-consistent way.

Although results provide important information on developing a web-MI, clients from these DUI programs may not be generalizable to clients in other DUI programs. In addition, we had only a small sample of monolingual Spanish-speaking clients as most of the Latino sample were bilingual and tested the English version of the web-MI. Future studies could examine client views in other geographical areas, over more DUI programs, and over several rounds of implementation in order to capture whether web-MI is acceptable and feasible in other non-White populations. Finally, while our results reflect important elements of MI, as one might expect, feedback from the clients on the web-MI did not always map onto the MITI global categories of evocation, collaboration, autonomy/support, and empathy in the same way in-person MI would. For example, it is difficult to know whether a client is accepting or resistant to information and offer empathy given there is no in-person interaction and “reading” of the client’s non-verbal behavior. This is an important limitation of web-MIs.

Strengths of this study include the involvement of both DUI program staff and clients in the intervention development process. Involving key stakeholders increases the likelihood of developing robust and sustainable treatments (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). Latinos are currently underrepresented in treatment programs (Schmidt, Ye, Greenfield, & Bond, 2007) and overrepresented in DUI programs (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Rodriguez, 2008; Hunter et al., 2006). Our finding that Spanish-speaking clients felt comfortable with the web-MI suggests it is a promising method to increase access to an intervention that may prevent recidivism. Providing a web-MI in DUI programs could help address disparities in access to evidence-based treatment for Latino clients with a first-time DUI offense. Future web-MI studies may incorporate information about treatment and treatment referrals for those who need it and are ready to take that step, and also offer other “aftercare” options for when clients end their AEP classes.

Finally, we built a module into the web-MI that addressed the effects of alcohol on depressed mood. Research suggests that untreated psychiatric co-morbidity might contribute to DUI recidivism (Hunter et al., 2006) and clients with depressed mood are more highly motivated and receptive to MI interventions (Wells-Parker, Dill, Williams, & Stoduto, 2006). Thus, incorporating co-occurring depression into web-MIs is important, and we plan to examine how mood may affect outcomes as part of our larger trial.

In sum, using the web to deliver an MI intervention for DUI clients was feasible and acceptable to the DUI staff and to the English and Spanish-speaking clients who had received a DUI and were mandated to receive treatment. Alcohol-related DUI accidents are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among Latinos, and the consequences are costly. Web-MIs make it possible to widely disseminate evidence-based protocols with high fidelity and at low costs and have the potential to reach at-risk populations that might not otherwise seek treatment. Future studies could examine the comparative effectiveness of web-MI compared to in-person MIs, the cost-effectiveness of web-MI compared to other DUI programs, and how outcomes may or may not differ by race and ethnicity. If web-MI is seen as a standalone intervention, future studies may also assess the extent to which clients comprehend the web-MI (e.g., post-web-MI quiz; Anger et al., 2004) to evaluate whether comprehension of the web-MI affects outcomes. We plan to address some of these issues as part of our larger randomized control trial comparing in-person MI to web-MI among English and Spanish-speaking clients with a first-time DUI offense (Watkins RC1AA019034).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the DUI programs for their support of this project and Elizabeth Maggio for her editorial assistance. The current study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (RC1AA019034) to Katherine Watkins.

References

- Anger WK, Tamulinas A, Uribe A, Ayala C. Computer-based training for immigrant Latinos with limited formal education. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(3):373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Anger WK, Stupfel J, Ammerman T, Tamulinas A, Bodner T, Rohlman DS. The suitability of computer-based training for workers with limited formal education: A case study from the US agricultural sector. International Journal of Training and Development. 2006;10(4):269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on long-term outcome in three alcohol-treatment modalities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2003;64(1):98–104. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Brief motivational intervention vs. computerized alcohol education with college students mandated to intervention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): Rates and predictors of DUI across Hispanic national groups. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2008;40(2):733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Henson JM, Maisto SA, DeMartini KS. Brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students: Comparison of face-to-face counseling and computer-delivered interventions. Addiction. 2011;106(3):528–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter T, Anez LM, Paris M, Suarez-Morales L, Szapocznik J, Miller WR, Rosa C, Matthews J, Farentinos C. A multisite randomized effectiveness trial of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance users. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):993–999. doi: 10.1037/a0016489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Martinez CR., Jr The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Marlatt GA. Epidemiological trends in drinking by age and gender: Providing normative feedback to adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DW, Carter JF. Translation procedures for the cross cultural use of measurement instruments. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1979;1(3):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Christophersen A, Skurtveit S, Grung M, Morland J. Rearrest rates among Norwegian drugged drivers compared with drunken drivers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Martin G. Web-based interventions for substance use disorders: A qualitative review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Wild TC, Cordingley J, Mierlo Tv, Humphreys K. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for alcohol abusers. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2023–2032. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Edelen MO. Pilot test of Project CHOICE: A voluntary afterschool intervention for middle school youth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):592–598. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Stern SA, Meredith LS. Brief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: A randomized pilot study in a primary care clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Hunter SB. Developing a group motivational interviewing intervention for adolescents at-risk for developing an alcohol or drug use disorder. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28(4):417–436. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2010.511076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Zhou AJ, Shih RA, Green HDJ. Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after school program for middle school students: Results from a custer randomized controlled trial of Project CHOICE. Prevention Science. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud SO, Tashima HN. Annual Report to the Legislature of the State of California. Sacramento, CA: Department of Motor Vehicles; 2007. Annual Report of the California DUI Management Information System. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Quevedo C, Rangil T, Sanchez-Planell L, Kroenke K, Spitzer R. Validation and utility of the patient health questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(4):679–686. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Tobler NS, Ringwalt CL, Flewelling RL. How effective is drug abuse resistance education? A meta-analysis of Project DARE outcome evaluations. American Journal Public Health. 1994;84(9):1394–1401. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW. Motivational Interviewing with minority youth. Paper presented at the 118th Annual American Psychological Association Convention; San Diego, CA, San Diego, CA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Sullivan M. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GC. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DV, Skewes MC, Resor MR, Villanueva MR, Hanson BS, Blume AW. A pilot test of an alcohol skills training programme for Mexican-American college students. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(4):320–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman F. Cultural adaptations of Alcoholics Anonymous to serve Hispanic populations. Substance Use and Misuse. 1994;29(4):445–460. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Weisner C. Use of exclusion criteria in selecting research subjects and its effect on the generalizability of alcohol treatment outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):588–594. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SB, Wong E, Beighley CM, Morral AR. Acculturation and driving under the influence: A study of repeat offenders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:458–464. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, Hartley S, Godfrey C. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(2):267–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Saunders JB, Gallagher SJ. Acceptability of various brief intervention approaches for hazardous drinking among university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003;38(6):626–628. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman-Castillo B, Beaty B, Raghunath S, Steiner J, Bull S. LUCHAR: Using computer technology to battle heart disease among Latinos. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(2):272–275. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Burhansstipanov L, Connell CM, Gielen AC, Helitzer-Allen D, Lorig K, Thomas S. A research agenda for health education among underserved populations. Health Education & Behavior. 1994;22(3):346–363. doi: 10.1177/109019819402200307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Rohsenow DJ. Cognitive processes in alcohol use: Expectancy and the balanced placebo design. In: Mello NK, editor. Advances in substance abuse: Behavioral and biological research. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1980. pp. 159–199. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(3):455–461. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Cuzmar I. Are special treatments needed for special populations? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2009;25(4):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Estrada D, Firpo-Jimenez M. Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal. 2000;8(4):341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan G, Fischoff B, Bostrom A, Atman CJ. Risk communication: A mental models approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) 2010 Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI3_1.pdf.

- Muñoz RF, Barrera AZ, Delucchi K, Penilla C, Torres LD, Perez-Stable EJ. International Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 year. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(9):1025–1034. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The Economic Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, Report No. DOT HS 809 446. Washington: Department of Transportation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts, Report No. DOT HS 810 631. Washington: Department of Transportation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts Research Note, Report No. DOT HS 810 936. Washington: Department of Transportation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J. Why You Only Need to Test with 5 Users. 2000 Retrieved June 14, 2010, from http://www.useit.com/alertbox/20000319.html.

- Ondersma SJ, Svikis DS, Schuster CR. Computer-based brief intervention: A randomized trial with post-partum women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osilla KC, dela Cruz E, Miles JN, Zellmer S, Watkins K, Larimer ME, Marlatt GA. Exploring productivity outcomes from a brief intervention for at-risk drinking in an employee assistance program. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osilla KC, Zellmer SP, Larimer ME, Neighbors C, Marlatt GA. A brief intervention for at-risk drinking in an employee assistance program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(1):14–20. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton MR, Williams J, Herman-Stahl M, Calvin SL, Bradshaw MR, Bray RM, Mitchell GM. Evaluation of two web-based alcohol interventions in the U.S. military. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(3):480–489. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WT, Lin J, Rinaldi CM. Validity of the simultaneous approach to the development of equivalent achievement tests in English and French. Applied Measurement in Education. 2011;24(1):39–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Helmuth ED, Aromaa SE, Guard A, Belanger M, Rosenbloom DL. Web-based screening and brief intervention for the spectrum of alcohol problems. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):969–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Horton NJ, Sullivan LM, Moskowitz MA, Samet JH. Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: A cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention. The screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(5):372–382. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente J, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: Results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, Ayala-Velazquez H, Echeverria L, Leo GI, Zioikowski M. Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: Alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Substance Use and Misuse. 2001;36(3):313–331. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano-Flores G, Trumbull E, Nelson-Barber S. Concurrent development of dual language assessments: An alternative to translating tests for linguistic minorities. International Journal of Testing. 2002;2(2):107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AC, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State & county Quickfacts: Los Angeles County, C.A. 2009 Retrieved December 15, 2010, from http://quickfacts.census.gov.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Usability Basics. 2010a Retrieved June 14, 2010, from http://usability.gov/basics/index.html.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Usability.gov: Your guide for developing usable & useful. 2010b Web sites Retrieved June 9, 2010, from http://www.usability.gov/

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Stephens RS. The check-up: in-person, computerized, and telephone adaptations of motivational enhancement treatment to elicit voluntary participation by the contemplator. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prevention Science. 2007;8(1):83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber RP. Basic content analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weidmer B, Brown J, Garcia L. Translating the CAHPS 1.0 survey instruments into Spanish. Medical Care. 1999;37(3 Suppl):MS89–MS96. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Parker E, Dill P, Williams M, Stoduto G. Are depressed drinking/driving offenders more receptive to brief intervention? Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(2):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Parker E, Williams M. Enhancing the effectiveness of traditional interventions with drinking drivers by adding brief individual intervention components. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;63(6):655–664. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Parker E, Kenne DR, Spratke KL, Williams MT. Self-efficacy and motivation for controlling drinking and drinking/driving: An investigation of changes across a driving under the influence (DUI) intervention program and of recidivism prediction. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(2):229–238. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SL, O’Neal KK. Project D.A.R.E. outcome effectiveness revisited. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(6):1027–1029. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Miller WR. The use of confrontation in addiction treatment: History, science, and time for change. Counselor. 2007;8(4):12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 to screen for depression in primary care in Honduras. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;4(5):191–195. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Evans PC, Clark LP. Alcohol addiction and perceived sanction risks: Deterring drinking drivers. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34(2):165–174. [Google Scholar]