Abstract

Objective

Mutations in the type IV collagen alpha 1 gene (COL4A1) cause dominantly inherited cerebrovascular disease. We seek to determine the extent to which COL4A1 mutations contribute to sporadic, non-familial, intracerebral hemorrhages (ICHs).

Methods

We sequenced COL4A1 in 96 patients with sporadic ICH. The presence of putative mutations was tested in 145 ICH–free controls. The effects of rare coding variants on COL4A1 biosynthesis were compared to previously validated mutations that cause porencephaly, small vessel disease and HANAC syndrome.

Results

We identified two rare non–synonymous variants in ICH patients that were not detected in controls, two rare non–synonymous variants in controls that were not detected in patients and two common non–synonymous variants that were detected in patients and controls. No variant found in controls affected COL4A1 biosynthesis. Both variants (COL4A1P352L and COL4A1R538G) found only in patients changed conserved amino acids and impaired COL4A1 secretion much like mutations that cause familial cerebrovascular disease.

Interpretation

This is the first assessment of the broader role for COL4A1 mutations in the etiology of ICH beyond a contribution to rare and severe familial cases and the first functional evaluation of the biosynthetic consequences of an allelic series of COL4A1 mutations that cause cerebrovascular disease. We identified two putative mutations in 96 patients with sporadic ICH and show that these and other previously validated mutations inhibit secretion of COL4A1. Our data support the hypothesis that increased intracellular accumulation of COL4A1, decreased extracellular COL4A1, or both, contribute to sporadic cerebrovascular disease and ICH.

Introduction

Strokes are common and devastating neurological events with poor clinical outcomes for which there are few effective treatments. Intracerebral hemorrhages (ICHs) are the most fatal and least treatable form of stroke. Although only accounting for 10–15% of all strokes, ICH is associated with the highest rate of mortality 1. Up to 50% of individuals die within the first year following ICH and the majority of survivors suffer life-long disability 2. Approximately 90,000 people suffer from ICH each year in the United States and this number is expected to double in the next 50 years as life expectancies increase 1. Current therapies offer little hope for substantially improving the outcome. Prevention is therefore of paramount importance for reducing the personal and societal burden of ICH. Identifying the genetic factors that predispose to ICH allows identification of individuals who are at greater risk and facilitates understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying disease and the promise of novel drug targets.

Sporadic ICH generally occurs in the elderly and most commonly occurs in the setting of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) or hypertensive vasculopathy. Epidemiological studies have identified modifiable risk factors that contribute to ICH, notably alcohol consumption, hypertension and cigarette smoking, but suggest that they account for only small proportions of the overall attributable risk3. Mutations in several genes are well established to contribute to familial syndromic ICH in the young, unfortunately, to date, these have not proven to contribute broadly to sporadic cases.

Dominant mutations in the gene coding for type IV collagen alpha 1 (COL4A1) cause highly penetrant cerebrovascular diseases, including ICH, and are being identified in an increasing number of patients 4–14. COL4A1 and its binding partner, COL4A2, are the most abundant and ubiquitous basement membrane proteins and are present in cerebral vascular basement membranes. One COL4A2 and two COL4A1 peptides assemble into heterotrimers within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) before being transported to the Golgi and secreted into the extracellular space 15, 16. Heterotrimers associate into a meshwork and form flexible sheets that provide structure and strength to basement membranes in the extracellular space. At the carboxy termini of COL4A1 and COL4A2 are globular domains responsible for conferring binding partner specificity and initiating heterotrimer formation within the ER 17. The amino terminal domains are responsible for higher–order inter–trimer associations in the extracellular matrix. The vast majority (> 90%) of the COL4A1 protein consists of a long, triple helix–forming domain composed of repeating Gly-Xaa-Yaa amino acid residues that are characteristic of collagens. Extensive data from many types of collagens in several species demonstrate that missense and splice site mutations that disrupt triple helix assembly cause protein misfolding and are highly pathogenic 18. This is also true for COL4A1. To date, 11 out of 13 mutations identified in mice 4, 19, 20 and 21 out of 24 mutations identified in human patients occur within the triple helix–forming domain 4–14, 21–23.

The phenotypes resulting from COL4A1 mutations are genetically complex and pleiotropic; often involving other organ systems. Mutations in COL4A1 have already been reported to underlie a spectrum of cerebrovascular diseases. We demonstrated that mice with a mutation in Col4a1 had pre– and perinatal ICH, porencephalic cavities, progressive, multi-focal and recurrent ICH, and, occasionally, sub–arachnoid hemorrhages 4, 5 in addition to other ocular, renal and muscular phenotypes 21. To date, we, and others, have discovered independent COL4A1 mutations in multiple patients with porencephaly 4, 6, 22–24 or with other forms of cerebrovascular diseases 5, 7–14, 22, 23. We identified a COL4A1 mutation in a French family diagnosed with a multi–system small–vessel disease that not only affected the cerebrovascular system but also the renal and retinal vasculature, demonstrating that COL4A1 mutations affect multiple organ systems in human patients 5. More recently mutations were identified in six families presenting with a multi–system disorder referred to as HANAC syndrome (Hereditary Angiopathy, Nephropathy, Aneurysms and Cramps); which is reported to be associated with milder cerebrovascular diseases than that observed in other patients with COL4A1 mutations 9, 13, 25, 26. The mutations in these patients cluster within a 31 amino acid region of the COL4A1 protein that encompasses putative integrin binding domains leading to the suggestion that allelic heterogeneity might contribute to the variable expressivity of COL4A1–related phenotypes. In addition to a potential role for allelic heterogeneity, we have shown that genetic context can modify the penetrance and severity of phenotypes caused by a Col4a1 mutation in mice 27 and that environmental factors (including birth trauma, anti-coagulant use and head trauma) also likely influence the clinical manifestation of disease in individuals with a COL4A1 mutation 5. Together, these data show that COL4A1 mutations can cause diverse forms of cerebrovascular disease and identify COL4A1 as a strong candidate for involvement in sporadic ICH.

Here, we investigated the potential role of COL4A1 mutations in sporadic (non–familial) ICH not caused by arteriovenous malformations, tumors or impaired coagulation. We identified two novel putative COL4A1 mutations in patients diagnosed with sporadic CAA, or presumed hypertension–related ICH. To test the biosynthetic consequences of these putative mutations, we developed and validated a cell culture-based functional assay using non–pathogenic polymorphisms and previously confirmed disease-causing mutations. We demonstrated that COL4A1 proteins containing a known mutation or one of the putative mutation identified in this study impair secretion of COL4A1 and lead to protein accumulation within cells. The findings presented herein raise the possibility that COL4A1 mutations may underlie a significant proportion of new cases of ICH every year in the United States and that therapies aimed at promoting protein folding might be effective in preventing hemorrhagic strokes in some patients.

Patients and Methods

Patient selection

Cases were selected from among 800 consecutive patients with ICH presenting to Massachusetts General Hospital. All individuals were prospectively characterized by neurologists without knowledge of this study, as well as by neuroimaging, and were categorized according to diagnostic criteria (the Boston Criteria) that have been developed and validated 28. For the present study, 48 individuals with probable CAA–related ICH and 48 individuals with presumed hypertension–related deep ICH were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria published previously 26 (summarized in SOM Table 1). Patients were chosen who had adequate DNA for sequencing and appropriate consent to share samples between institutions. The details for the patients included in this study are listed in Table 1. During the collection of patient samples we obtained DNA from ethnically and age–matched individuals that were free of a history of hemorrhagic stroke and who were drawn from the primary care practices at Massachusetts General Hospital. All participants provided informed consent for participation and the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Table 1.

Patient Features

| Patient Details | CAA-related ICH | Deep ICH |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number | 48 | 48 |

| Mean Age in years (SD) | 74 (9) | 69 (14) |

| Female (%) | 46 | 33 |

| Hypertension (%) | 52 | 88 |

| Mean ICH Vol. in cc (SD) | 54 (36) | 42 (42) |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 96 | 75 |

| Black | 2 | 10 |

| Asian | 0 | 15 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 0 |

| Ethanol use (%) | ||

| Never | 38 | 58 |

| <3oz/week | 42 | 13 |

| 3oz/week-3oz/day | 10 | 8 |

| >3oz/day | 2 | 4 |

| Smoking (%) | ||

| Non-smokers | 42 | 38 |

| Yes (Variant Dose) | 8 | 0 |

| <1 pack/day | 2 | 0 |

| 1 pack/day | 0 | 2 |

| >1 pack/day | 4 | 8 |

| Quit <5 years | 4 | 6 |

| Quit >5 years | 33 | 31 |

Genomic sequence analysis

Genomic DNA (10ng/μL) was amplified using 44 sets of primers 21 that cover the entire coding sequence for each exon in addition to the flanking intronic regions (50 nucleotides for most introns but never less than 20 nucleotides) of COL4A1. Direct sequencing was performed using ABI BigDye v3.1 and analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation).

Functional analysis of COL4A1 variants

HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells were transfected using Superfect reagent (Qiagen) with the expression vector pReceiver-M02 vector (GeneCopoeia) containing a CMV promoter upstream of a control (NM_001845.2) or variant COL4A1 cDNA clone. Variants were introduced by site directed mutagenesis performed at GeneCopoeia or using a QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). After 12 days of G418 selection (600 μg/ml), individual surviving clones were isolated and expanded in presence of 600 μg/ml of G148.

Stably transfected HT1080 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, glutamine, sodium pyruvate, G418 (250 μg/ml for maintenance), 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in a humid atmosphere until they reach 80–90% confluence. Ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) was added overnight and the following day cells were serum deprived for 24h in the presence of ascorbic acid. Cells were then harvested and lysed in Laemmli buffer for subsequent Western blot analysis. The conditioned medium was collected at the same time and supplemented with protease inhibitors (Pierce).

Proteins present in the whole cell lysate and conditioned medium were separated on 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (BioRad). Membranes were blocked for 2 hours at room temperature in 5% non-fat milk in Tris–buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20, and overnight at 4°C in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS. Membranes were then incubated with a rat anti–COL4A1 (H11) monoclonal antibody (1:150, Shigei Medical Research Institute, Japan) in 1% BSA in TBS for 3 hours at room temperature and were washed in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, incubated 2 hours at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody raised in donkey (anti–rat IgG 1:10 000, Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted in 5% non-fat milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Immunoreactivity was visualized using chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL, Amersham). Densitometric analysis was performed on low exposure images using the NIH Image J software (National Institutes of Health). For quantitative analysis of the ratio of secreted to intracellular COL4A1 protein, the amount of COL4A1 detected in the conditioned medium was divided by the amount of intracellular COL4A1.

Results

We re–sequenced all 52 exons of COL4A1, including flanking intronic sequences, for the selected patient cohort (Table 1) and we identified 65 sequence variants – 19 coding and 46 non-coding (SOM Table 2). Of the 19 coding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 4 were non–synonymous and 15 were synonymous variants (Table 2). We re–sequenced 290 control chromosomes for each exon in which a coding variant was found. We identified an additional 7 SNPs in control samples; 3 were non–coding, 2 were coding and synonymous and 2 were coding and non–synonymous.

Table 2.

Coding SNPs Identified

| NON-SYNONYMOUS CODING SNPs

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Exon | Codon | Amino Acid | Patients | Controls | Distribution | ||||||

| Homozygous Major | Heterozygous | Homozygous Minor | Total | Homozygous Major | Heterozygous | Homozygous Minor | Total | |||||

| 2 | 1 | GTC -> CTC | Val 7 Leu | G/G (20) | G/C (37) | C/C (30) | 87 | G/G (54) | G/C (57) | C/C (31) | 142 | Both |

| 8 | 7 | GCT -> GTT | Ala 144 Val | C/C (90) | C/T (0) | T/T (0) | 90 | C/C (141) | C/T (2) | T/T (0) | 143 | Control |

| 31 | 19 | CCG -> CTG | Pro 352 Leu | C/C (93) | C/T (1) | T/T (0) | 94 | C/C (145) | T/C (0) | T/T (0) | 145 | Case |

| 38 | 25 | CGG -> GGG | Arg 538 Gly | C/C (88) | C/G (1) | G/G (0) | 89 | C/C (141) | C/G (0) | G/G (0) | 141 | Case |

| 58 | 45 | CAA -> CAC | Gln 1334 His | A/A (33) | A/C (37) | C/C (18) | 88 | A/A (64) | A/C (64) | C/C (13) | 141 | Both |

| 63 | 49 | ATG -> GTG | Met 1531 Val | A/A (89) | A/G (0) | G/G (0) | 89 | A/A (143) | A/G (1) | G/G (0) | 144 | Control |

|

SYNONYMOUS CODING SNPs | ||||||||||||

| SNP | Exon | Codon | Amino Acid | Patients | Controls | Distribution | ||||||

| Homozygous Major | Heterozygous | Homozygous Minor | Total | Homozygous Major | Heterozygous | Homozygous Minor | Total | |||||

| 7 | 7 | GAG -> GAA | Glu 131 Glu | G/G (90) | G/A (0) | A/A (0) | 90 | G/G (141) | G/A (2) | A/A (0) | 143 | Control |

| 9 | 7 | GCT -> GCA | Ala 144 Ala | T/T (28) | T/A (39) | A/A (23) | 90 | T/T (43) | T/A (76) | A/A (24) | 143 | Both |

| 19 | 12 | GAC -> GAT | Asp 230 Asp | C/C (88) | C/T (1) | T/T (0) | 89 | C/C (144) | C/T (0) | T/T (0) | 144 | Case |

| 35 | 21 | CCT -> CCC | Pro 419 Pro | T/T (51) | T/C(32) | C/C (8) | 91 | T/T (65) | T/C (66) | C/C (14) | 145 | Both |

| 37 | 23 | GAC -> GAT | Asp 473 Asp | C/C (86) | C/T (1) | T/T (0) | 87 | C/C (145) | C/T (0) | T/T (0) | 145 | Case |

| 39 | 25 | CCG -> CCA | Pro 567 Pro | G/G (88) | G/A (1) | A/A (0) | 89 | G/G (141) | G/A (0) | A/A (0) | 141 | Case |

| 40 | 26 | CCT -> CCC | Pro 605 Pro | T/T (79) | T/C (9) | C/C (0) | 88 | T/T (125) | T/C (18) | C/C (0) | 143 | Both |

| 41 | 26 | GGA -> GGG | Gly 627 Gly | A/A (87) | A/G (1) | G/G (0) | 88 | A/A (143) | A/G (0) | G/G (0) | 143 | Case |

| 45 | 29 | GGG -> GGA | Gly 708 Gly | G/G (89) | G/A (1) | A/A (0) | 90 | G/G (145) | G/A (0) | A/A (0) | 145 | Case |

| 46 | 29 | CCG -> CCA | Pro 710 Pro | G/G (42) | G/A (36) | A/A (12) | 90 | G/G (65) | G/A (57) | A/A (23) | 145 | Both |

| 51 | 37 | GGG -> GGA | Gly 1061 Gly | G/G (40) | G/A (36) | A/A (13) | 89 | G/G (63) | G/A (61) | A/A (21) | 145 | Both |

| 52 | 37 | CGA -> CGT | Arg 1063 Arg | A/A (40) | A/T (36) | T/T (13) | 89 | A/A (63) | A/T (61) | T/T (21) | 145 | Both |

| 57 | 45 | GGC -> GGT | Gly 1332 Gly | C/C (88) | C/T (0) | T/T (0) | 88 | C/C (139) | C/T (2) | T/T (0) | 141 | Control |

| 59 | 45 | GGC -> GGT | Gly 1335 Gly | C/C (87) | C/T (1) | T/T (0) | 88 | C/C (141) | C/T (0) | T/T (0) | 141 | Case |

| 62 | 49 | GCC -> GCT | Ala 1490 Ala | C/C (45) | C/T (32) | T/T (12) | 89 | C/C (63) | C/T (62) | T/T (19) | 144 | Both |

| 69 | 51 | TCC -> TCT | Ser 1600 Ser | C/C (74) | C/T (12) | T/T (2) | 88 | C/C (121) | C/T (23) | T/T (0) | 144 | Both |

| 70 | 52 | ACG -> ACA | Thr 1646 Thr | G/G (86) | G/A (1) | A/A (0) | 87 | G/G (145) | G/A (0) | A/A (0) | 145 | Case |

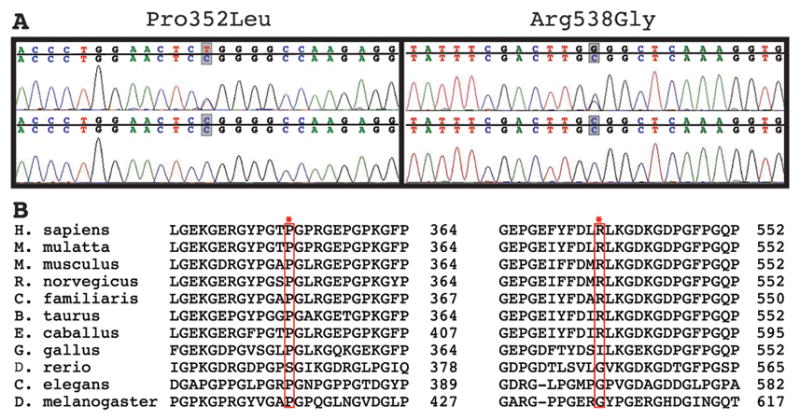

Two sporadic (non–familial) ICH patients had non–synonymous SNPs that were not found in ethnically–matched control chromosomes. Patient 1 was a 73-year-old Hispanic woman who presented with a generalized tonic–clonic seizure followed by left-sided weakness in the setting of oral warfarin anticoagulation therapy for aortic valve replacement (admission INR: 2.8). CT imaging identified a small right temporal ICH (8 cubic centimeters) and MRI identified lobar microbleeds, thus qualifying the patient for a diagnosis of probable CAA according to the Boston Criteria 28. This patient had a cytidine to thymidine transition at nucleotide c.C1055T in exon 19 that resulted in a proline to leucine substitution at position 352 of the peptide sequence (COL4A1P352L), which corresponds to the Y position of a Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeat within the triple–helix–forming domain of the protein (Fig 1). This variant was not identified in 290 control chromosomes. As shown in an alignment of COL4A1 orthologues from 11 species, a proline residue at this position is highly conserved across all species (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Electropherograms of genomic DNA from patients (top panels) reveal a C to T transition resulting in a Pro352Leu amino acid change and a C to G transversion resulting in an Arg538Gly amino acid change. (B) Multi–species alignment of COL4A1 orthologues shows that both putative mutations occur in highly conserved amino acids.

Patient 2 was a 55-year old man of European-American ancestry presenting with a large right putaminal ICH (bleeding volume at presentation was 65 cubic centimeters) causing acute onset left arm, face and leg weakness and depressed consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale: 8). Medical history was significant for hypertension, type 2 diabetes and aspirin use (81 mg/day). The ICH location and history of hypertension are consistent with a diagnosis of probable hypertensive hemorrhage. The variant found in Patient 2 is a cytidine to guanosine transversion at nucleotide c.C1612G in exon 25, leading to an arginine to glycine substitution at position 538 (COL4A1R538G) of the COL4A1 peptide sequence (Fig 1). This putative mutation was not identified in 282 control chromosomes. As illustrated in an alignment of COL4A1 orthologues from 11 species, the arginine residue is conserved in all mammals (Fig 1).

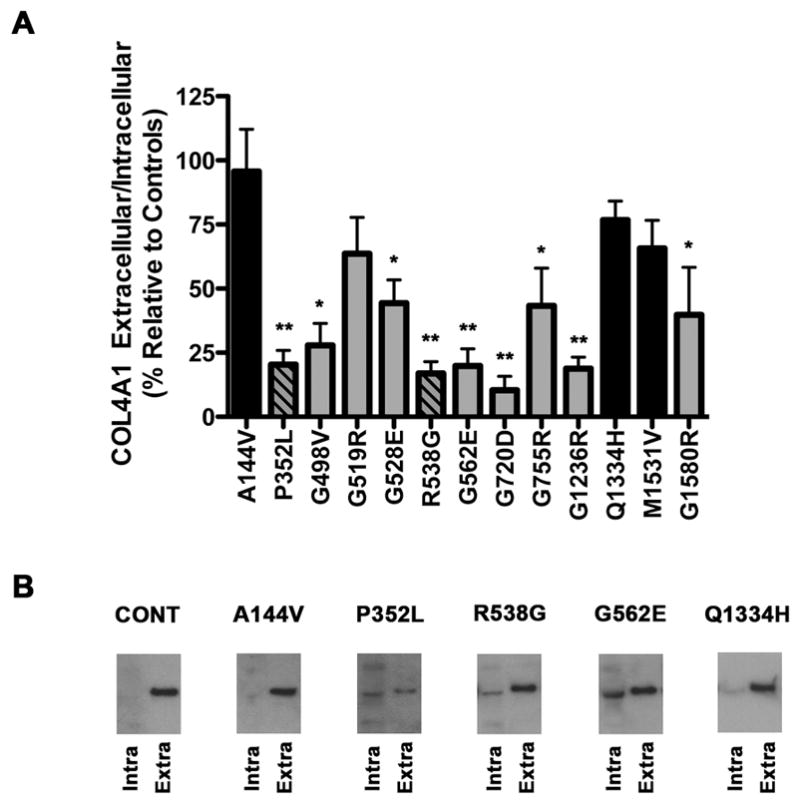

Missense mutations within the triple–helix–forming domain of many different types of collagens from many different species disrupt heterotrimer formation leading to decreased heterotrimer secretion and subsequent intracellular accumulation of misfolded proteins. To test the hypothesis that COL4A1P352L and COL4A1R538G might lead to impaired secretion of the COL4A1/A2 heterotrimers, we measured the relative ratio of extracellular to intracellular COL4A1 using a cell culture–based secretion assay that we previously established to test putative mutations 21. We first confirmed that a highly polymorphic variant found across cohorts (COL4A1Q1334H) did not significantly alter the extracellular to intracellular ratio when compared to the control cDNA sequence (NM_001845.2). We then tested two rare variants that were found only in our control cohort (COL4A1A144V and COL4A1M1531V) and we did not observe a significant effect of these variants on the extracellular to intracellular ratio. In contrast, with one exception (COL4A1G519R; discussed below), transfection with COL4A1 cDNA containing validated mutations (Table 3) occurring within the triple-helix forming domain (COL4A1G498V, COL4A1G528E, COL4A1G562E, COL4A1G720D, COL4A1G755R, COL4A1G1236R) or in the NC1 domain (COL4A1G1580R), caused a significant reduction in the ratio of extracellular to intracellular COL4A1 when compared to cells transfected with control cDNA (Fig 2). Similarly, when we tested the functional consequences of the two rare variants found only in our patient cohort (COL4A1P352L and COL4A1R538G) we found that both variants were significantly different from controls (Fig 2, p<0.01). Thus, these results support the hypothesis that intracellular COL4A1 accumulation, at the expense of its secretion, is a common consequence of COL4A1 mutations and that the two putative mutations identified in our cohort have the same effect on COL4A1 biosynthesis as previously validated mutations.

Table 3.

List of known COL4A1 disease-causing mutations

| Mutation | Associated Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| COL4A1G498V | HANAC | Plaisier et al., 2007 |

| COL4A1G519R | HANAC | Plaisier et al., 2007 |

| COL4A1G528E | HANAC | Plaisier et al., 2007 |

| COL4A1G562E | Small Vessel Disease | Gould et al., 2006 |

| COL4A1G720D | ICH and Ocular Dysgenesis | Sibon et al., 2007 |

| COL4A1G755R | Cerebrovascular Disease | Shah et al., 2009 |

| COL4A1G1236R | Porencephaly | Gould et al., 2005 |

| COL4A1G1580R | Porencephaly | de Vries et al., 2006 |

FIGURE 2.

(A) Western blot analysis of the extracellular to intracellular ratio of COL4A1 from HT1080 cells stably transfected with control COL4A1 cDNA or with cDNAs containing different variants. Values are expressed as percentage of the control COL4A1 ratio and are presented as mean +/− SEM. Black bars indicate variants found in the control cohort, grey bars indicate mutations previously reported and striped bars indicate putative mutations identified in this study. The quantification is the result of multiple independent experiments using at least 6 unique clones for each variant. (B) Is a representative Western blot images from one experiment showing intracellular (Intra) and extracellular (Extra) COL4A1 for HT080 cells transfected with control COL4A1 cDNA (indicated as CONT) or with COL4A1 cDNA containing a variant only present in control subjects (COL4A1A144V), the putative mutations identified in patients in this study (COL4A1P352L and COL4A1R538G), an established pathogenic mutation (COL4A1G562E) or a common variant (COL4A1Q1334H). A total of six independent clones for each variant were used for this analysis, *p<0.05, **p < 0.01. Both putative mutations, COL4A1P352L and COL4A1R538G, had significant reductions in the extracellular to intracellular ratio of COL4A1 (p<0.01) when compared to control (two–tailed Student’s t–test).

Interpretation

The current study represents the first assessment for a broader involvement of COL4A1 mutations in the etiology of ICH. We re–sequenced all coding and flanking intervening sequences for the entire COL4A1 gene and identified two putative mutations in patients that were not present in 145 ethnically–matched control individuals. Both mutations resulted in missense changes in amino acids that are highly conserved across species. Functional analysis demonstrated that both the COL4A1P352L and the COL4A1R538G variants impair secretion of COL4A1. Proline residues in the Y position of the triple–helix–forming domain are highly conserved and 210 out of 436 Gly–Xaa–Yaa repeats within the triple helix–forming domain have a proline residue in the Y position. During collagen biosynthesis, prolines are converted to hydroxyprolines, which are critical for cross–linking of collagen heterotrimers 29 and it may be that the COL4A1P352L mutation impairs this process. In addition, frequent interruptions in the Gly–Xaa–Yaa repeats are thought to confer flexibility to type IV collagen molecules. COL4A1 has 21 repeat interruptions that align with 23 interruptions in COL4A2. The COL4A1R538G variant occurs within a repeat interruption and shortens the interruption from a seven amino acid interruption to a four amino acid interruption (from GEP GEF YFDLRLK GDK to GEP GEF YFDL GLK GDK), which could lead to abnormal alignment of peptides within the heterotrimer and therefore interfere with proper heterotrimer assembly and secretion.

Our data testing the effects of established mutations on collagen biosynthesis suggest that the intracellular retention of mutant COL4A1 proteins at the expense of their secretion appears to be a common effect of many COL4A1 mutations. The extents to which intracellular and/or extracellular insults contribute to pathology remain an open question. Intracellular accumulation of COL4A1 could lead to cytotoxic stress. On the other hand, deficiency of COL4A1 or the presence of mutant COL4A1 in the extracellular matrix could also have detrimental consequences. For example, reduced or mutant COL4A1 in the basement membrane could physically compromise blood vessels 30, or disrupt protein–protein interactions with extracellular molecules, including other basement membrane components, growth factors 31, 32 or cell surface receptors.

The absence of morphologically engorged endoplasmic reticulum in a renal biopsy from a patient with a COL4A1G498V mutation led to the hypothesis that mutations clustering near putative integrin binding domains, and which have been associated with HANAC syndrome, might act on integrin signaling13. Here, we have tested three of these mutations (COL4A1G498V, COL4A1G519R and COL4A1G528E) for the efficiency with which the mutant proteins are secreted. We find that two of these mutations, including COL4A1G498V, have significant decreases in the extracellular to intracellular COL4A1 ratio, while the COL4A1G519R mutation shows a trend toward a reduced ratio that was not statistically significant (Fig 2). This apparent discrepancy may reflect that, in vivo, cells do not have intracellular accumulation like we detected in vitro. It might also be that there is accumulation of COL4A1 in vivo but that the effect is transient or not fully penetrant and its detection requires a much larger sample size for electron microscopy that can be practically accomplished in human biopsies. Therefore, it may be that this subset of COL4A1 mutations do not affect protein folding in vivo, however the evidence to date is inconclusive. Interestingly, the COL4A1R538G variant identified in one of our patients also occurs within a putative integrin–binding site (GEFYFDLRLKGDK) 33, 34. However, this mutation shortens the length of a repeat interruption and leads to strong intracellular accumulation and so the potential significance of any effect on the putative integrin–binding site is not clear. Therefore, although protein misfolding is associated with most COL4A1 mutations, the precise molecular mechanisms by which mutations lead to cerebrovascular diseases are still unknown and may exhibit allelic and mechanistic heterogeneity.

Determining allelic and mechanistic heterogeneity of COL4A1 mutations will be important for developing innovative therapeutics to prevent ICH in patients. To this end, evaluating if genotype/phenotype correlations exist between different mutant alleles in mice maintained on a uniform genetic context and under controlled environmental conditions could be important for understanding the pathogenic mechanisms contributing to COL4A1–related pathologies. Moreover, irrespective of the location of the insult (intracellular, extracellular, or both) it is possible that conditions that promote protein folding will both reduce intracellular accumulation and increase extracellular secretion thereby having a beneficial effect. Indeed this proved to be the case in C. elegans with mutations in Col4a1 and Col4a2 orthologues whereby pathology was rescued by growth at reduced temperatures35–37. These data suggest that chemical chaperones or other small molecules that promote protein folding could be efficacious in reducing the risk of ICH in some patients with COL4A1 mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a research grant from the American Heart Association (DBG), and by NIH-NINDS R01NS059727 (SMG and JR). Salary support was also provided by the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation (DBG for YCW), Research to Prevent Blindness (DBG for WBK), American Heart Association (DBG for CLD), Hersenstichcting (MdL) and American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research (0775010N) (AB). Additional support was provided by a core grant from the National Eye Institute (EY02162) and a Research To Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant (UCSF Department of Ophthalmology).

Literature Cited

- 1.Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1450–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA, et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:880–884. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.8.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo D, Sauerbeck LR, Kissela BM, et al. Genetic and environmental risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage: preliminary results of a population-based study. Stroke. 2002;33:1190–1195. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014774.88027.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould DB, Phalan FC, Breedveld GJ, et al. Mutations in Col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science. 2005;308:1167–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1109418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould DB, Phalan FC, van Mil SE, et al. Role of COL4A1 in small-vessel disease and hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1489–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breedveld G, de Coo IF, Lequin MH, et al. Novel mutations in three families confirm a major role of COL4A1 in hereditary porencephaly. J Med Genet. 2006;43:490–495. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahedi K, Kubis N, Boukobza M, et al. COL4A1 mutation in a patient with sporadic, recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:1461–1464. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibon I, Coupry I, Menegon P, et al. COL4A1 mutation in Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly with leukoencephalopathy and stroke. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:177–184. doi: 10.1002/ana.21191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaisier E, Gribouval O, Alamowitch S, et al. COL4A1 mutations and hereditary angiopathy, nephropathy, aneurysms, and muscle cramps. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:2687–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vries L, Koopman C, Groenendaal F, et al. COL4A1 mutation in two preterm siblings with antenatal onset of parenchymal hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:12–18. doi: 10.1002/ana.21525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah S, Kumar Y, McLean B, et al. A dominantly inherited mutation in collagen IV A1 (COL4A1) causing childhood onset stroke without porencephaly. European journal of paediatric neurology. 2010;14:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouaud T, Labauge P, Tournier Lasserve E, et al. Acute urinary retention due to a novel collagen COL4A1 mutation. Neurology. 2010;75:747–749. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plaisier E, Chen Z, Gekeler F, et al. Novel COL4A1 mutations associated with HANAC syndrome: A role for the triple helical CB3[IV] domain. American journal of medical genetics. 2010;Part A doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilguvar K, Diluna ML, Bizzarro MJ, et al. COL4A1 Mutation in Preterm Intraventricular Hemorrhage. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155:743–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayne R, Wiedemann H, Irwin MH, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against chicken type IV and V collagens: electron microscopic mapping of the epitopes after rotary shadowing. The Journal of cell biology. 1984;98:1637–1644. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trüeb B, Gröbli B, Spiess M, et al. Basement membrane (type IV) collagen is a heteropolymer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1982;257:5239–5245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoshnoodi J, Cartailler J-P, Alvares K, et al. Molecular recognition in the assembly of collagens: terminal noncollagenous domains are key recognition modules in the formation of triple helical protomers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:38117–38121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel J, Prockop DJ. The zipper-like folding of collagen triple helices and the effects of mutations that disrupt the zipper. Annual review of biophysics and biophysical chemistry. 1991;20:137–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Agtmael T, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, McKie L, et al. Dominant mutations of Col4a1 result in basement membrane defects which lead to anterior segment dysgenesis and glomerulopathy. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:3161–3168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favor J, Gloeckner CJ, Janik D, et al. Type IV procollagen missense mutations associated with defects of the eye, vascular stability, the brain, kidney function and embryonic or postnatal viability in the mouse, Mus musculus: an extension of the Col4a1 allelic series and the identification of the first two Col4a2 mutant alleles. Genetics. 2007;175:725–736. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labelle-Dumais C, Dilworth DJ, Harrington EP, et al. COL4A1 Mutations Cause Ocular Dysgenesis, Neuronal Localization Defects, and Myopathy in Mice and Walker-Warburg Syndrome in Humans. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meuwissen MEC, de Vries LS, Verbeek HA, et al. Sporadic COL4A1 mutations with extensive prenatal porencephaly resembling hydranencephaly. Neurology. 2011;76:844–846. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820e7751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermeulen RJ, Peeters-Scholte C, Van Vugt JJM, et al. Fetal origin of brain damage in 2 infants with a COL4A1 mutation: fetal and neonatal MRI. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42:1–3. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Knaap MS, Smit LME, Barkhof F, et al. Neonatal porencephaly and adult stroke related to mutations in collagen IV A1. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:504–511. doi: 10.1002/ana.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plaisier E, Alamowitch S, Gribouval O, et al. Autosomal-dominant familial hematuria with retinal arteriolar tortuosity and contractures: a novel syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2354–2360. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alamowitch S, Plaisier E, Favrole P, et al. Cerebrovascular disease related to COL4A1 mutations in HANAC syndrome. Neurology. 2009;73:1873–1882. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c3fd12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gould DB, Marchant JK, Savinova OV, et al. Col4a1 mutation causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and genetically modifiable ocular dysgenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:798–807. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology. 2001;56:537–539. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg RA, Prockop DJ. The thermal transition of a non-hydroxylated form of collagen. Evidence for a role for hydroxyproline in stabilizing the triple-helix of collagen. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1973;52:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)90961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pöschl E, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, et al. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:1619–1628. doi: 10.1242/dev.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paralkar VM, Vukicevic S, Reddi AH. Transforming growth factor beta type 1 binds to collagen IV of basement membrane matrix: implications for development. Developmental biology. 1991;143:303–308. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90081-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Harris R, Bayston L, Ashe H. Type IV collagens regulate BMP signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miles AJ, Skubitz AP, Furcht LT, Fields GB. Promotion of cell adhesion by single-stranded and triple-helical peptide models of basement membrane collagen alpha 1(IV)531–543. Evidence for conformationally dependent and conformationally independent type IV collagen cell adhesion sites. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30939–30945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauer JL, Gendron CM, Fields GB. Effect of ligand conformation on melanoma cell alpha3beta1 integrin-mediated signal transduction events: implications for a collagen structural modulation mechanism of tumor cell invasion. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5279–5287. doi: 10.1021/bi972958l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta MC, Graham PL, Kramer JM. Characterization of alpha1(IV) collagen mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans and the effects of alpha1 and alpha2(IV) mutations on type IV collagen distribution. The Journal of cell biology. 1997;137:1185–1196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham PL, Johnson JJ, Wang S, et al. Type IV collagen is detectable in most, but not all, basement membranes of Caenorhabditis elegans and assembles on tissues that do not express it. The Journal of cell biology. 1997;137:1171–1183. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sibley MH, Graham PL, von Mende N, Kramer JM. Mutations in the alpha 2(IV) basement membrane collagen gene of Caenorhabditis elegans produce phenotypes of differing severities. The EMBO journal. 1994;13:3278–3285. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.