Abstract

The possibility that memory awareness occurs in nonhuman animals has been evaluated by providing opportunity to decline memory tests. Current evidence suggests that rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) selectively decline tests when memory is weak (Hampton, 2001; Smith, Shields, & Washburn, 2003). (R.R. Hampton, 2001; Smith, Shields, & Washburn, 2003). However, much of the existing research in nonhuman metacognition is subject to the criticism that, after considerable training on one test type, subjects learn to decline difficult trials based on associative learning of external test-specific contingencies rather than by evaluating the private status of memory or other cognitive states. We evaluated whether such test-specific associations could account for performance by presenting monkeys with a series of generalization tests across which no single association with external stimuli was likely to adaptively control use of the decline response. Six monkeys performed a four alternative delayed matching to location task and were significantly more accurate on trials with a decline option available than on trials without it, indicating that subjects selectively declined tests when memory was weak. Monkeys transferred appropriate use of the decline response under three conditions that assessed generalization: two tests that weakened memory and one test that enhanced memory in a novel way. Bidirectional generalization indicates that use of the decline response by monkeys is not controlled by specific external stimuli but is rather a flexible behavior based on a private assessment of memory.

Keywords: memory awareness, metacognition, explicit memory, monitoring, declarative memory

Most modern taxonomies of human memory make a fundamental distinction between explicit (declarative) memories we can become aware of and implicit (non-declarative) memories we cannot cognitively access in the same way (Clark, Manns, & Squire, 2002; Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991). Memory awareness, a form of metacognition or thinking about thinking (e.g. Nelson, 1996), is the ability to monitor explicit memories. Humans often use monitoring to make adaptive decisions based on the status of cognitive processes (Flavell, 1979; Metcalfe, 2008; Smith, Redford, Beran, & Washburn, 2010). For example, before offering to explain to the class of the causes of World War II, a student might gauge the strength of her memory for this event in history. If she finds that the memory is strong and she is confident about specific details she will offer a public explanation. If, however, her internal assessment reveals a weak or non-existent memory, she will choose not to raise her hand. When such adaptive judgments of memory performance can be shown to depend on memory awareness, they demonstrate the presence of explicit memory.

Because much of the evidence for memory awareness in humans comes from verbal reports not available from nonhumans, it is challenging to develop parallel tests for nonverbal species. Comparative psychologists have, however, developed a set of tests in which nonhumans avoid difficult tests, collect more information when needed, or “gamble” food rewards appropriately based on recent performance, arguably demonstrating memory awareness (Basile, Hampton, Suomi, & Murray, 2008; Call & Carpenter, 2001; Hampton, 2001; Hampton, Zivin, & Murray, 2004; Inman & Shettleworth, 1999, Kornell, Son, & Terrace, 2007; Roberts et al, 2009; Smith, Shields, & Washburn, 1998; Suda-King, 2008; Sutton & Shettleworth).These studies assess whether or not memory awareness is fundamental to the organization of memory in species other than humans. By studying metacognition in nonhuman animals, especially in our close primate relatives, researchers begin to address the general question of when and why cognitive awareness evolved. The recent findings in nonhuman metacognition research challenge long standing positions of philosophers and human metacognition researchers that metacognitive abilities are uniquely human (Carruthers, 2008). Due to the difficulties in inferring private cognitive process in nonhumans, it is especially important for research in nonhuman metacognition to make use of controls, generalization tests, and converging approaches that can discriminate among alternative explanations.

The first studies of animal metacognition used perceptual rather than memory paradigms. Dolphins (Smith et al., 1995), monkeys and humans (Shields, Smith, & Washburn, 1997) made one of two judgments about a psychophysical stimulus (e.g. sparse or dense image, high or low tone), or made a third response to decline the test. Subjects were more likely to decline difficult tests in which stimuli were close to perceptual threshold than they were to decline easy ones. Such appropriate use of the decline response suggests that subjects monitored the status of perceptual cognition and chose to take tests when cognition proceeded effectively to a conclusion. Researchers expanded upon these original psychophysical tests by demonstrating similar adaptive use of a decline response in rhesus monkeys (Beran, Smith, Redford, & Washburn, 2006; Smith & Washburn, 2005) , pigeons (Sole, Shettleworth, & Bennett, 2003), and rats (Foote & Crystal, 2007). Others used retrospective betting paradigms to address the same questions (Kornell, Son, & Terrace, 2007; Nakamura, Watanabe, Betsuyaku, & Fujita, 2011).

While appropriate selection of the decline response on difficult trials may indicate awareness of private mental states, metacognitive responding can also be controlled by publicly available information (e.g. Beran, Smith, Coutinho, Couchman, & Boomer, 2009; Crystal & Foote, 2009; Hampton, 2009; Jozefowiez, Staddon, & Cerutti, 2009; Smith, Beran, Couchman, & Coutinho, 2008). In psychophysical tasks subjects make judgments about the external stimuli and these stimuli themselves may control the decline response. It is possible, for example, that the availability of the decline option trains animals to divide stimulus dimensions into three categories (e.g. sparse, dense, and intermediate). Subjects might then use the “decline” response to indicate they perceive a stimulus in the intermediate range, rather than indicating the qualitatively different state of uncertainty. In memory awareness tasks, subjects are asked to make judgments about memory, which is a representation that is internal, and not present in the external world. Though psychophysical tasks presumably ask subjects also to make a decision about an internal representation of a stimulus, the external stimulus is still present in the environment such that perception of that stimulus itself, rather than its representation, may control selective responding (Metcalfe, 2008). Tests of memory awareness, which are not as stimulus bound as perceptual tests of metacognition (Metcalfe, 2008), may therefore circumvent some problems associated with perceptual tests.

Unlike psychophysical tasks on which most vertebrates tested seem to demonstrate metacognition, only primates have demonstrated convincing evidence for memory awareness. In the first study of memory awareness in monkeys (Smith, Shield, & Washburn, 1998), rhesus monkeys were presented with a list of items and at test judged whether a probe item did or did not appear in the studied list. Memory for items in the lists showed primacy and recency effects (Sands & Wright, 1980), and monkeys were more likely to decline difficult trials, on which test items came from the middle of the list than easy trials when first and last items in the list were tested (Smith, et al., 2003). Because the pattern of declining trials mirrored primary performance on the memory tests, it appears that monkeys discriminated between strong and weak memories.

Though memory awareness paradigms emphasize control of the decline response by internal cognitive states rather than external stimuli, these tests are not invulnerable to non-introspective explanations of metacognitive responding. Generalization tests are the best approach to evaluating the influence of external stimuli that are specific to a given testing situation. Successful generalization excludes control of metacognitive responding by any discriminative stimulus that is not present across the conditions over which generalization is obtained. Metacognition in monkeys has generalized across some variations in testing conditions (Hampton, 2001; Kornell, et al., 2007; Smith, Redford, Beran, Washburn, 2006). For example, monkeys selectively declined tests when memory was weak, achieving higher accuracy on memory tests with a decline test option available, and then generalized use of the decline response in two novel test conditions (Hampton, 2001). In a generalization test, omission of the sample increased use of the decline test response. In a second generalization tests, monkeys immediately used the decline test response more on long delay than on short delay interval trials. Transfer in these generalization tests suggests that it is memory awareness that underlies subjects’ behavior, rather than response to external stimuli that are indirectly associated with memory status (Hampton, 2001; Hampton, 2009).

It is possible that salient features of the unusual probe tests caused subjects to decline trials. Because all of the probe trials were designed to weaken or eliminate memory, it is not possible to determine whether monkeys declined probes because they were unusual and unexpected, or because they had the effect of decreasing memory. More behavioral research with a larger number of subjects is needed to test the robustness of the finding that monkeys know when they remember (Metcalfe, 2008; Shettleworth, 2010, p.249). Towards this end we trained a group of six monkeys in a naturalistic spatial memory paradigm with a memory awareness component. Critically, we used a novel generalization test in which memory was increased by presenting the sample twice. By increasing memory on these unusual probe trials (Experiment 4), while decreasing it on others (Experiments 2 & 3), we directly contrast the hypothesis that all unusual or unexpected tests will be declined, with the hypothesis that monkeys monitor memory and decline tests when memory is weak. If monkeys decline all unusual trials, they should increase use of the decline response whether probe manipulations increase or decrease memory. In contrast, if they monitor memory, they should decrease decline responses when memory is increased, and increase use of the decline response on probe trials where memory is decreased.

General Methods

Subjects

Six male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta; mean age = 6.2 years) were tested. Monkeys were pair-housed with water available ad libitum, and were fed a full ration of food each day. Each monkey had access to his cage-mate at all times except during testing and normal feeding at the end of the day, when the two monkeys in each pair were separated by an opaque divider.

Apparatus

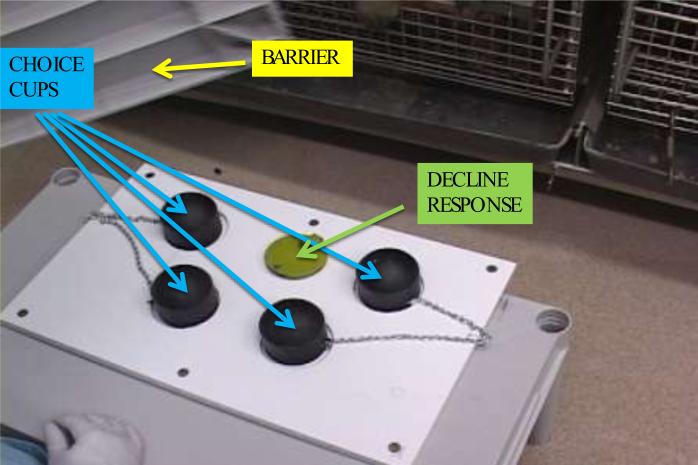

A test tray (50.3 cm length × 30.5 cm width) containing five food wells was used (Figure 1). Four identical black PVC pipe end-caps (8.1 cm diameter × 6.35 cm height) were used to cover four wells that concealed the primary food rewards. The subjects could lift or knock over one of these choice cups to retrieve two raisins hidden under one of them. A fifth, smaller well centered between the two front choice cups was covered by a circular green disk could be made available as the decline response. When available, monkeys could push on the green disk to rotate it off the well, revealing a single raisin. The test tray sat on a short table such that the height of the table matched the height of a chow holes on the front of the monkey cages, allowing the monkeys to reach out to the food cups when the tray was moved up against the front of the cage. A grey plastic barrier (45.7 cm long, 38.1 cm width, and 3.81 cm depth; Figure 1) was used to completely block the monkey's view of the cups during delay intervals and inter-trial intervals.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the testing tray. The tray was pushed forward to the monkey's cage during the choice phase of trials. One of the four black choice cups normally contained two raisins. The flat green disk provided a decline-test option rewarded with a single raisin and was present only on choice trials. The opaque barrier visible in the top left of the photograph was used to obscure the monkeys’ view of the test tray between trials and during delay intervals.

General Procedure

Monkeys were tested in their home cages. Prior to testing, a separation panel was placed between a pair of connected cages to confine each monkey to one cage. During the study phase of each trial the experimenter lifted one of the black choice cups, placed two raisins in the well, and placed the cup back over the food well. The location of the two raisins was pseudo-randomized across trials with the constraint that the same location could not be baited more than four times consecutively and each location was used equally often in each session. After a delay, during which the monkeys’ view of the apparatus was block by an opaque panel, the tray was pushed forward to the edge of the monkey's cage so that the cups could be reached.

If the monkey chose the baited cup he retrieved two raisins, if he selected an incorrect cup he received nothing. On trials where the decline response was available, one raisin was also concealed under the green disk (see Figure 1) but this was done before the trial began, out of sight of the monkey behind the opaque barrier. If the monkey displaced the green disk, he retrieved the raisin. Monkeys were never allowed more than one choice per trial. The tray was immediately withdrawn after the monkey selected a cup, correct or not, or the green disk. The visual barrier was then placed between the experimenter and subject while the testing tray was prepared for the next trial. The next trial began as soon as the tray was ready and the monkey was facing forward and could see the baiting of the choice cups. The experimenter wore a darkened face shield, similar to a welder's mask, in order to eliminate facial and gaze cues.

Data analysis & behavior scoring

On each trial the cup the monkey first touched was recorded as his choice. Attempts to select additional cups, including the decline option, were prevented and not recorded. Proportions were arcsine transformed before statistical analysis to better approximate the normality assumption underlying parametric statistics (Keppel & Wickens, 2004, p. 155). The Geisser-Greenhouse correction was used, and appropriately adjusted degrees of freedom reported, whenever the sphericity assumption was violated (Keppel & Wickens, 2004, p. 378).

Training Procedures

Phase 1: Choice with a single distracter

Training began with just the two cups closest to the subject; the back two cups were removed from the tray (Figure 1). A randomly chosen cup was baited in full view of the monkey. After a delay of about 3 seconds, the monkey was allowed to choose a cup. If the monkey chose incorrectly, the trial was repeated up to two times. If the monkey chose incorrectly on the third try, only the baited cup was presented, ensuring that the monkey was rewarded for selecting the cup at the baited location. After achieving 80% correct first choices in each of two consecutive 10 trial sessions subjects progressed to Phase 2.

Phase 2: Visual barrier introduction

Trials were conducted as in Phase 1 except that a visual barrier was placed between the tray and the subject immediately after the cup was baited. The barrier was removed after the 3 second delay and the tray was pushed forward to the monkey. Monkeys progressed to Phase 3 after achieving 80% correct in each of two consecutive 10 trial sessions.

Phase 3: Transition to 4 choice cups

Phase 3 was identical to Phase 2 expect that four cups were used rather than 2. Subjects advanced to Phase 4 once accuracy was 70% or better in each of two consecutive 10 trial sessions.

Phase 4: Delay titration

Phase 4 was identical to Phase 3 except that the delays between study and test were increased for each monkey individually until performance stabilized between 40 and 70% correct. This level of performance ensured that monkeys would have experience with both remembering and forgetting the location of the hidden food, a necessary precursor for learning to use the decline response appropriately. Correction trials were given as in previous phases.

Each monkey was given one 10 trial session per day. Testing began with a 3 second delay. If a monkey was correct 70% or more in each of two consecutive sessions, his delay was doubled. If accuracy fell to 40% or below for each of two consecutive sessions, the delay was decreased to the previous delay. When the delay had not been changed for 10 sessions, this delay was set as the criterion delay for that monkey and he progressed to Phase 5 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Accuracies during initial training, and delays, in seconds, assigned to each monkey in Experiments 1 and 4.

| Stage of training/testing | Delay/specifics | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training accuracy | No decline available | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Training accuracy | Decline available | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.67 |

| Experiment 1 | Final criterion delay | 12 s | 6 s | 6 s | 12 s | 48 s | 48 s | |

| Experiment 4 | Increased delay | 24 s | 18 s | 12 s | 36 s | 144 s | 96 s |

Phase 5: Introduction of the decline response

To ensure that monkeys knew that a single raisin was available under the green decline response disk, each session began with 4 trials in which only the decline response was available. Ten trials followed in which the procedure was as in Phase 4 except that in addition to the four choice cups, the decline response was also available on all trials, and no correction procedure was used. Monkeys received 20 sessions at their established criterion delay, and then moved on to Experiment 1.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 provided the first opportunity to assess whether monkeys selectively declined memory tests when memory was poor. Monkeys were given the option of declining tests on the majority of trials, but also received randomly intermixed trials on which the decline test response was not available. When memory is weak, monkeys with memory awareness should opt for the decline response rather than running the risk of receiving no raisins by guessing where the two raisins were located. When memory is strong, and they have a high probability of choosing the correct choice cup, they should select the remembered cup and retrieve the preferred reward of two raisins. The memory awareness hypothesis therefore predicts that monkeys should perform better on trials they choose to take than they do on tests they are forced to take because the decline response is not available. This is because accuracy on forced trials is a weighted average of accuracy on tests monkeys would have declined, had they had the option, and those that they would have chosen to take anyway. If monkeys lack memory awareness and therefore select the decline response at random with respect to memory strength they should perform equally well on forced and chosen trials.

Methods

Subjects and apparatus

All subjects and apparatus were the same as those used in training.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that used in training except that forced test trials on which the decline response disk was not available were randomly intermixed with choice trials on which the decline response was available. Six of the 18 trials in each session were forced trials; the remaining 12 trials were choice trials. Each monkey received 15 sessions at their criterion delay.

Some monkeys’ performance improved with further experience after training, putting accuracy outside of the 40-70% ranged needed for this test. If a monkey's accuracy on forced trials averaged 70% or above across 5 sessions that monkey's delay was doubled and he was required to complete a full 15 sessions at the new delay.

Results & Discussion

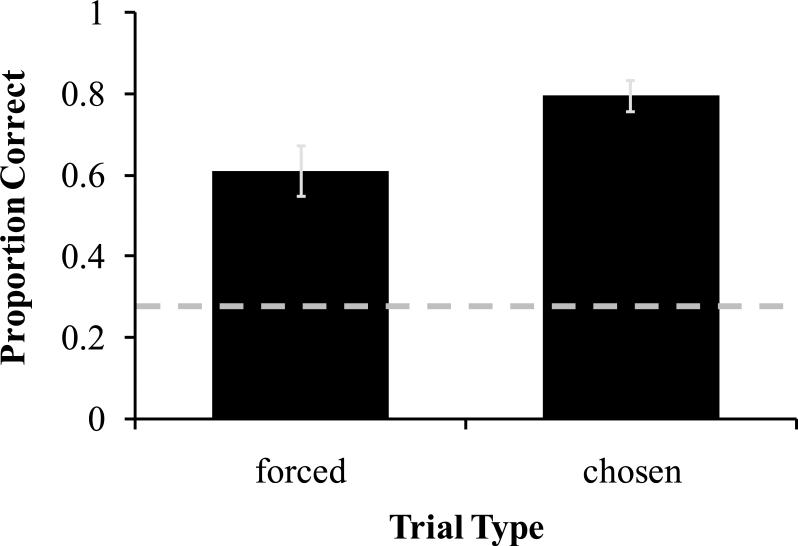

The performance of two monkeys, M1 and M4, exceeded 70% accuracy on forced tests, triggering an increase in delay from 6 seconds used in training to a final criterion delay of 12 seconds (Table 1). All monkeys completed 15 sessions at their final criterion delay. Accuracy was higher on chosen tests than on forced tests (Figure 2; two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5 =-7.76, p< .001). These results indicate that when given the option to decline tests, monkeys used memory awareness to selectively decline tests when memory was poor. Accuracy was also significantly higher on chosen tests than forced tests (two-tailed, paired sample t-test: t5 =-2.83, p= .037) in the first session of testing (changed criterion delays of M1 and M4 were analyzed).

Figure 2.

Average accuracy on forced tests and chosen tests in Experiment 1. Chance, .25, is indicated by the dashed line. Error bars are standard errors of the means.

These results are consistent with memory awareness, but other factors could also have controlled decisions to take or decline tests. Monkeys may have been more accurate when particular baiting locations were used, and might have declined tests selectively whenever baiting occurred at difficult locations, rather than choosing to decline tests because memory was poor. Accuracy was indeed higher when either of the two front cups was baited than when either of the back cups was used (two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5=3.87, p=.012). Accordingly, monkeys declined back cup trials significantly more than front cup trials (two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5=-7.19, p<.001).

The fact that monkeys declined tests more often when one of the back cups was baited and they were likely to respond incorrectly is consistent with the hypothesis that monkeys’ chose to decline tests when memory was weak. This pattern of declining harder tests and accepting easier tests is the primary evidence for metacognition in many studies (e.g. Smith et al, 1998; Smith et al, 2005). However, it is also possible that because baiting location correlated with the probability of reinforcement, baiting location became a discriminative stimulus for declining or taking tests (see Hampton, 2009). The next experiments address this issue by de-confounding cup location and the accuracy of memory.

Experiment 2

Higher accuracy on chosen than on forced trials in Experiment 1suggests memory awareness. It is possible, however, that external sources of stimulus control, like cup location, may have contributed to performance. To test whether use of the decline response was under external stimulus control or was based on assessment of memory strength, novel empty trials, on which no choice cup was baited, were randomly intermixed with trials on which baiting was done normally. Omitting the bating on no sample trials brings memory under direct experimental control, creating trials on which monkeys have no memory of the baiting. These no sample trials are evenly distributed across locations. If memory awareness controls the decline response, monkeys should decline no sample tests much more frequently than normal trials. If baiting location controls the decline response, monkeys should decline no sample tests less frequently than they decline normal tests because cup location is not available to use as a discriminative stimulus for the decline response on trials on which no cup is baited.

Methods

Subjects and apparatus

All subjects and apparatus were the same as in Experiment 1.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that used in Experiment 1 except that 6 no sample probe trials were randomly intermixed among 12 normal choice trials to produce a session of 18 trials. No forced trials were included. Probe trials differed from regular trials only in that no choice cup was baited. The criterion delay was used for both trial types. After the inter-trial interval, the visual barrier was kept in place, blocking the monkey's view of the test tray, for the duration of the delay period. The tray was then pushed within reach of the monkey as in the test phase of normal trials. Monkeys received 5 sessions.

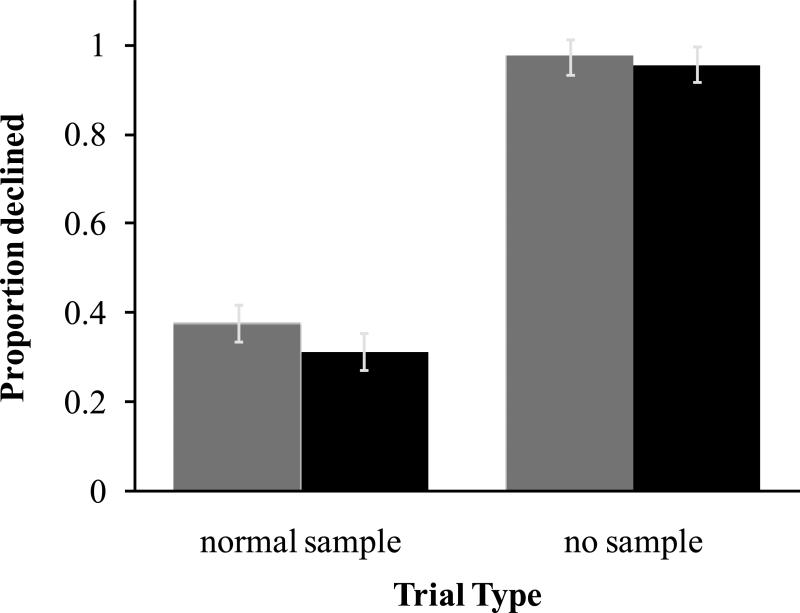

Results & Discussion

Monkeys declined no sample probe trials significantly more than normal trials (Figure 3, black bars; two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5=-16.1, p <.001). Because the experimental manipulation of memory produced this significant difference, these results support the conclusion that monkeys’ ability to selectively decline tests is based on detecting an absence of memory rather than cueing by external events specific to difficult trials.

Figure 3.

Probability of the decline response on normal trials, on which a choice cup was baited, and on no sample trials, on which no choice cup was baited in Experiment 2. Grey bars represent the first session only, consisting of 6 no sample probe trials and 12 normal trials per monkey. Black bars represent average performance across all 5 sessions, totaling 30 probes and 60 normal trials. Error bars are standard errors of the mean.

Though few no sample trials were presented, some distinctive feature of the probe trial could have gained stimulus control over the decision to decline tests (R.R. Hampton, 2001; 2009). The first session with no sample trials was therefore analyzed separately to test whether learning could account for use of the decline response. In the first session monkeys declined probe tests significantly more than normal trials (Figure 3, grey bars; two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5= -9.37, p<.001). Two monkeys, M3 and M6, never took a memory test on no sample probe trials, and thus never experienced the negative consequences of choosing a cup on probe trials. The other four monkeys had few experiences with choosing a cup on no sample trials: M4, M1 and M5 selected a choice cup only once and M2 did so 5 times in 30 opportunities. It is therefore unlikely that the decline response is under direct control by external stimuli, and more likely that use of this response reflects assessment of memory strength.

It is improbable that cup location guided subjects to decline tests because no cup was baited on no-sample probes. If the source of stimulus control was cup location monkeys should have declined no sample probes significantly less in probe trials than on normal trials on which one of the back two cups was baited. In fact, the opposite was found: the rate of declining was significantly higher on no sample trials than on trials on which one of the back two cups was baited (two-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t(5)=9.08, p<.001). As predicted by the memory awareness hypothesis, monkeys declined no sample probe trials significantly more than they declined both normal back cup trials and all normal trials combined. No sample probe trials experimentally simulate normal trials on which monkeys happen to forget the correct reward location and strengthen the case that the choice to decline memory tests is based on memory awareness.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, we experimentally manipulated memory in a second way. Rather than eliminating memory entirely by omitting the sample, we manipulated the probability of forgetting by varying the length of the delay interval. Monkeys using memory awareness should decline tests following long delay intervals more often than those following short delays because they are more likely to have forgotten the location of the two raisins after long, rather than short, delays.

Methods

Procedures were identical to previous experiments except that trials with short and long delays were randomly intermixed with trials with each monkey's criterion delay. Each 18 trial session contained 6 trials with a 3 second delay, 6 trials with a 96 second delay, and 6 trials with each monkey's criterion delay, which fell between the 3 and 96 second extremes. Of each set of 6 trials at each delay, 4 were chosen trials and 2 were forced. Monkeys received 20 sessions.

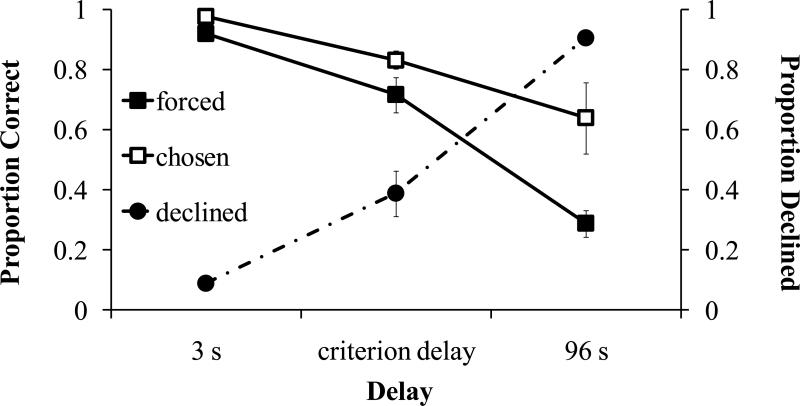

Results & Discussion

Monkeys were more accurate on short delay than on long delay trials, and were more accurate on chosen than on forced trials (Figure 4; 2×2 factorial ANOVA; delay: F1, 10=26.2, p=.003; trial type: F1, 5=17.2, p=.009; delay × trial type: F2, 10=1.87, p=.205). These results indicate that monkeys choose to take tests when they remember and decline tests when they do not. Monkeys were most likely to decline trials at long delays, less likely at intermediate delays, and least likely at short delays (repeated-measures ANOVA: F2, 10=95.01, p< .001; Bonferroni test correction for multiple pair-wise comparisons). Comparisons between all delays were significant; p< .005; Figure 4; filled circles). At 3 second delays subjects declined tests less than 1% of the time, while at a 96 second delay period they declined tests 91% of the time, indicating that monkeys adaptively declined trials when memory was poor while taking tests when memory was strong. Some interpretations of the use of memory awareness in this experimental situation would predict a significant interaction between delay and trial type, such that accuracy on chosen trials would stay relatively flat across delays but performance on forced trials would decline. The present results show this pattern qualitatively, but the interaction is not significant. Monkeys chose to take few tests at the long delays, and this may make such interactions difficult to detect statistically.

Figure 4.

Performance on forced and chosen tests after a short delay (3 s), medium delay (6, 12, 24, 48 s depending on the monkey's criterion delay), and long delay (96 s) in Experiment 3. The proportion of correct trials for forced (filled squares) and chosen (open squares) tests corresponds with the left y-axis. Proportion of trials declined (filled circles) corresponds to the right y-axis. Error bars are standard errors of the means.

In Experiment 2 monkeys declined tests when no sample had been presented and they could therefore have no memory of a sample. In the present experiment we manipulated memory strength in a second, more graded way, by varying the delay. Monkeys’ use of the decline response tracked the decline in accuracy that occurred at longer delay intervals, further supporting the conclusion that metacognitive responding was controlled by the private assessment of memory strength, rather than publicly-available sources of stimulus control.

Experiment 4

In Experiment 2 subjects treated no sample probe trials like trials in which they forgot the location of the food; in Experiment 3 long delays caused monkeys to frequently forget the location of the food and they were more likely to use the decline response on these trials than on trials with shorter delays. Both the manipulations used in these experiments decreased memory with the same result: monkeys used the decline response more when memory was attenuated on trial types they had not experienced before. It appears that monkeys declined tests due to a decrease or absence of memory. An alternative explanation is that monkeys decline tests whenever something unusual occurs during a trial, for example a delay longer than ever experienced before, or the absence of a sample. In Experiment 4 we address this hypothesis by using unusual probe trials to increase, rather than to decrease memory. A sample presented multiple times should be remembered better than one presented only once (e.g. Roberts, 1972). If it is memory awareness rather than unusual events that controls use of the decline response, then the proportion of declined tests should decrease on double sample tests. If, however, any unusual event causes monkeys to decline tests, the number of declined tests should increase on double sample trials.

Methods

The apparatus, subjects, and general procedure was identical to previous experiments. Double sample probe trials were presented on a random one-third of trials to increase memory for the location of the food. On these probe trials, the correct choice cup was lifted, the two raisins were placed in the corresponding well on the tray, and the cup was placed over the raisins, just as in normal trials. The cup was then lifted for a second time such that the monkey could clearly see which cup hid the reward. The delay interval then commenced as usual. Each session consisted of 6 double sample trials and 12 normal trials, pseudo-randomly intermixed. Two thirds of both trial types were chosen trials, and one third were forced trials. Monkeys received 10 sessions.

Because performance at the criterion delays had likely increased as a result of the training and testing that had occurred since they were initially established in Experiment 1 and because we required baseline performance to be low enough to provide an opportunity for memory to improve on double sample trials, criterion delays were doubled. Monkeys were tested on normal forced trials at the doubled delay for one session. If their performance fell in between 40 and 70%, this delay was used in the current experiment. M1, M3, and M6 met this criterion. The accuracies of M2, M4, and M5 were above 70% correct, so the criterion delay for these monkeys was tripled. These final delays are indicated in Table 1. These delays were used on both double sample and normal trials.

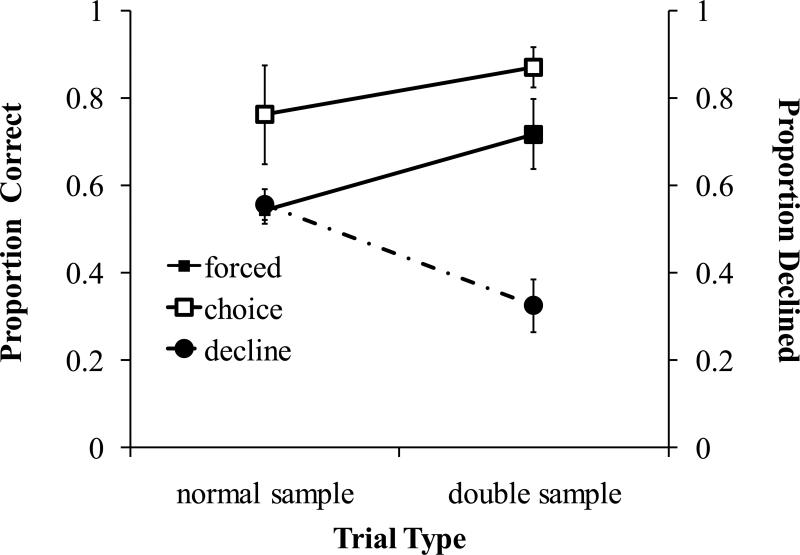

Results & Discussion

Accuracy on double sample trials was significantly higher than on normal trials (Figure 5, forced; one-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5=2.167, p=.041). Monkeys declined tests significantly less frequently on double sample trials than on normal trials (Figure 5, declined; one-tailed, paired-sample t-test: t5=3.22, p=.0115). These results show that monkeys do not decline tests just because they are novel or unexpected. If this were the case, subjects would have declined the double sample tests more than the single sample tests. Instead, subjects declined double sample trials significantly less frequently than normal trials, supporting the hypothesis that monkeys used memory awareness to guide their decisions to take or decline tests.

Figure 5.

Average accuracy on forced and chosen trials beginning with either normal or double samples in Experiment 4. Accuracies correspond to the left y-axis while probability of the decline response is indexed on the right y-axis. Error bars are standard errors of the means.

General Discussion

Across these experiments, monkeys appeared to avoid tests when their memories were weak and took tests when their memories were strong. In Experiment 1 monkeys performed significantly better on chosen than forced tests, indicating that when given the opportunity, they selectively declined tests when memory was poor. The remaining experiments evaluated the extent to which use of the decline response generalized to novel conditions and is based on a flexible process rather than being controlled by stimuli specific to one test situation. In Experiment 2 omission of the sample phase of trials caused subjects to decline tests significantly more often than they did on normal trials, indicating that they treated trials without a sample like trials on which they had seen, but forgotten the sample. In Experiment 3, monkeys frequently declined tests after long delays when memory was weak, and rarely declined tests after short delays when memory was strong, again showing that when memory was directly manipulated, monkeys responded immediately with appropriate use of the decline response. A novel generalization test used in Experiment 4 increased memory by presenting the to-be-remembered sample twice at the beginning of some trials. Rather than declining these novel probe trials more frequently than normal trials, which would be the case if they used the decline response whenever something unexpected occurred, they declined fewer tests when their memory was increased in this unusual way. Successful generalization across these novel test situations indicates that use of the decline response is controlled by an internal memory state that was modulated by a variety of manipulations of external events, rather than by any specific external stimuli. Together, the four experiments presented here provide strong evidence that memory awareness underlies use of the decline response.

Potential sources of stimulus control for metacognitive responding

It is reasonable to conclude that monkeys have memory awareness only if metacognitive responding is based on an internal assessment of memory strength. But metacognitive patterns of behavior can result from other sources of stimulus control. We adopt a broad definition of metacognition (Hampton, 2009) that allows for control by either external or internal stimuli, so that these alternative explanations can be considered within a common metacognitive framework.

In Experiment 1 cup location could have controlled use of the decline response. On forced choice trials, monkeys were less accurate when one of the back two cups was baited than when one of the front two cups was correct. It is therefore possible that monkeys declined trials based on which cup was baited. Experiment 2 eliminated this source of potential stimulus control: no cup was baited. Monkeys immediately generalized and declined tests with no baiting. Experiment 3 and 4 also rule out stimulus control by the location of the baited cup. In Experiment 3, the three delays were randomly intermixed such that different delays occurred equally across all the locations. In Experiment 4 each cup location was equally likely to be the sample on double baiting probes. Monkeys again generalized adaptive use of the decline response in these experiments, using it more often after long delays and less often after double samples. Therefore, use of the decline response could not have been controlled by cup location, making it more likely that the monkeys monitored memory and responded to the effects these manipulations had on memory.

Before making errors, subjects may vacillate between options or take a relatively long time to make a choice (Hampton, 2009). Because these external behaviors are associated with differences in accuracy, they could come to act as discriminative stimuli for the decline response (Crystal & Foote, 2009; Jozefowiez, Staddon, & Cerutti, 2009; Smith, Beran, Couchman, & Coutinho, 2008). Data on vacillation and latency were not collected in this study, so we cannot evaluate this hypothesis. One way to eliminate the possibility that response latencies or other behavioral events might account for use of the decline response is to present the decision to take or decline the test before the actual memory test occurs in a prospective memory awareness test (Fujita, 2009; Hampton, 2001). When the choice to take or decline tests is presented before the memory test, there is no opportunity for vacillations, response latencies, or other behavioral cues to control the choice to take or decline tests. Suda-King (2008) described a similar test conducted with orangutans as using a prospective memory awareness judgment. Unfortunately because the choice cups were in full view of the subject during the metacognitive choice, it does not seem justified to describe the judgment as prospective in the sense of judging memory before seeing the test.

When the decline response and the primary memory test are presented simultaneously, as was done in the present study, performance of the memory test is put in direct conflict with use of the decline response. This creates the possibility that the decline response was used only when the tendency to choose one of the choice stimuli was weak. On trials in which the monkey forgot the baited location, the tendency to choose a cup is decreased, thereby increasing the probability of selecting the concurrently available decline response. Correspondingly, on trials in which the animal clearly remembers the baited cup, the tendency to reach for the baited cup may overpower the tendency to choose the decline response (Call, 2010; Hampton et al. 2004). This response competition account has been evaluated in tests in which the value of the reward at stake on a given trial was varied in an information seeking paradigm. Apes were more likely to confirm the location of hidden food before making a choice when the reward was highly valued (Call, 2010). The response competition hypothesis predicts the opposite result: after seeing a highly valued reward hidden, subjects should have an especially strong tendency to reach for it rather than engaging in information seeking. Response competition can alternatively be eliminated by use prospective metacognitive judgments. With a prospective judgment, the test is out of sight while subjects choose to decline or take it and responses to the test stimuli cannot be in conflict with the metacognitive response.

It is possible that response competition may have transferred to performance on generalization tests. For example, in Experiment 4, baiting the choice cup twice may have increased the propensity to respond to the target cup, making it more likely that this response would out-compete the tendency to make the decline response. Double baiting was intended to increase memory strength and increase the probability that monkeys would select the choice cup, rather than decline the test as a consequence of memory monitoring. Memory did appear to be increased, as shown by enhanced performance on forced tests with double samples. However, with the paradigm, it is difficult to directly contrast memory strength and response strength. This remains a problem to be addressed by future studies of memory awareness, possibly through more use of prospective memory awareness paradigms.

Comparison with orangutans

Monkeys in the present study were tested using a spatial memory paradigm similar to that used with orangutans. Surprisingly, the orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) failed to show reliable evidence for memory awareness (Suda-King, 2008). Only one of five orangutans was significantly more accurate on chosen tests than on tests she was forced to take (Suda-King, 2008). The lack of robust evidence for memory awareness in orangutans is puzzling because there is existing evidence of memory awareness in apes, and orangutans specifically, from other tests (Call & Carpenter, 2001). Because apes are more closely related to humans than are monkeys, it seems unlikely that monkeys have memory awareness but orangutans do not.

One potentially significant difference between this study and that of Suda-King (2008) is that in the orangutan study the choice cup locations were moved after the subject chose to take the test but before the subject selected a particular choice cup. The apes watched the baiting of a preferred reward in one of the two identical choice cups and either chose to take the test by pointing to the choice cups or declined the test by selecting the decline-response cup which contained a less preferred reward. If the choice cups were chosen, the two cups which had been arranged in a straight line one behind the other were then separated and moved to distinct locations on the tray such that the apes had to visually track a moving hiding location. This may have introduced errors due to failures of visually tracking of the moving cups. As these errors come after the metacognitive choice, they would degrade the accuracy of the metacognitive judgment.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that rhesus monkeys are aware of some memories and that human memory taxonomies that distinguish between implicit and explicit memory can be applied to nonhumans. It is likely that memory awareness existed in the common ancestors of humans and rhesus monkeys at least as long as 30 million years ago (Gibbs et al., 2007), before old world monkeys diverged from apes and humans. While it is possible that metacognition evolved even earlier, before the split between new world monkeys and old world monkeys, strong evidence of metacognition in new world monkeys is currently lacking (Basile et al., 2008; Beran et al. 2009; Fujita, 2009). The behavioral evidence for memory awareness presented here provides a foundation for further behavioral and neurobiological studies of explicit memory in which direct comparisons between human and non-human primate can be made. Such studies may provide insight into the evolutionary foundations of memory awareness and other forms of explicit cognition.

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was submitted in partial fulfillment for a master's thesis at Emory University. Joseph Manns, Stella Lourenco, and Jocelyn Bachevalier provided helpful comments on an early draft. This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. R01MH082819 and the National Science Foundation Grant No. 0000017475. Additional support was provided by the Yerkes Center base grant No. RR-00165 awarded by the Animal Resources Program of the National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience under the STC Program of the National Science Foundation under Agreement No. IBN-9876754. These experiments comply with US law.

References

- Basile BM, Hampton RR, Suomi S, Murray EA. An assessment of memory awareness in tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Anim Cogn. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0180-1. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-01801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Smith JD, Coutinho MVC, Couchman JJ, Boomer J. The Psychological Organization of “Uncertainty” Responses and “Middle” Responses: A Dissociation in Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus apella). J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2009;35(3):371–381. doi: 10.1037/a0014626. doi: 10.1037/a0014626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Smith JD, Redford JS, Washburn DA. Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) monitor uncertainty during numerosity judgments. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2006;32(2):111–119. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.2.111. doi: 2006-04791-001 [pii]10.1037/0097-7403.32.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call J. Do apes know that they could be wrong? Anim Cogn. 2010;13(5):689–700. doi: 10.1007/s10071-010-0317-x. doi: 10.1007/s10071-010-0317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call J, Carpenter M. Do apes and children know what they have seen? Anim Cogn. 2001;4:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers P. Meta-cognition in animals: A skeptical look. Mind & Language. 2008;23(1):58–89. [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Manns JR, Squire LR. Classical conditioning, awareness, and brain systems. Trends Cog Sci. 2002;6(12):524–531. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)02041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman JJ, Coutinho MVC, Beran MJ, Smith JD. Beyond Stimulus Cues and Reinforcement Signals A New Approach to Animal Metacognition. J Comp Psychol. 2010;124(4):356–368. doi: 10.1037/a0020129. doi: 10.1037/a0020129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal JD, Foote AL. Metacognition in animals. Comparative Cognition and Behavior Reviews. 2009;4:1–16. doi: 10.3819/ccbr.2009.40001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell JH. Meta-cognition and cognitive monitoring-new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Amer Psychol. 1979;34(10):906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Foote AL, Crystal JD. Metacognition in the rat. Curr Biol. 2007;17(6):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K. Memory awareness in tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Animal Cognition. 2009;12(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0217-0. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Katze MG, Bumgarner R, Weinstock GM, Mardis ER, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316(5822):222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RR. Rhesus monkeys know when they remember. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5359–5362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071600998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RR. Multiple demonstrations of metacognition in nonhumans: converging evidence or multiple mechanisms? 2009 doi: 10.3819/ccbr.2009.40002. Available from http://psyc.queensu.ca/ccbr/index.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hampton RR, Zivin A, Murray EA. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) discriminate between knowing and not knowing and collect information as needed before acting. Anim Cogn. 2004;7:239–254. doi: 10.1007/s10071-004-0215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman A, Shettleworth SJ. Detecting memory awareness in nonverbal subjects: A test with pigeons. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1999;25(3):389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Jozefowiez K, Staddon JER, Cerutti DT. Metacognition in animals: how do we know that they know? 2009 Available from http://psyc.queensu.ca/ccbr/index.html.

- Keppel G, Wickens TD. Design and analysis, a researchers handbook. 4th ed. Pearson; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, Son LK, Terrace HS. Transfer of metacognitive skills and hint seeking in monkeys. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(1):64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J. Evolution of Metacognition. In: Bjork JDRA, editor. Handbook of memory awareness and memory. Psychology Press; New York: 2008. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Watanabe S, Betsuyaku T, Fujita K. Do birds (pigeons and bantams) know how confident they are of their perceptual decisions? Anim Cogn. 2011;14(1):83–93. doi: 10.1007/s10071-010-0345-6. doi:10.1007/s10071-010-0345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TO. Consciousness and metacognition. Amer Psychol. 1996;51(2):102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WA. Short-term memory in pigeons-effects of repetition and spacing. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1972;94(1):74. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WA, Feeney MC, McMillan N, MacPherson K, Musolino E, Petter M. Do Pigeons (Columba livia) Study for a Test? J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2009;35(2):129, 142. doi: 10.1037/a0013722. doi: 10.1037/a0013722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SF, Wright AA. Serial probe recognition performance by performance by a rhesus monkey and a human with 10-item and 20-item lists. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1980;6(4):386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shettleworth SJ. Cognition, Evolution, and Behavior. 2 ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shields WE, Smith JD, Washburn DA. Uncertain responses by humans and rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) in a psychophysical same-different task. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1997;126(2):147–164. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.126.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Beran MJ, Couchman JJ, Coutinho MVC. The comparative study of metacognition: Sharper paradigms, safer inferences. Psychon Bull & Review. 2008;15(4):679–691. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.4.679. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Redford JS, Beran MJ, Washburn DA. Dissociating uncertainty responses and reinforcement signals in the comparative study of uncertainty monitoring. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2006;135(2):282–297. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.135.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Redford JS, Beran MJ, Washburn DA. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) adaptively monitor uncertainty while multi-tasking. Anim Cogn. 2010;13(1):93–101. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0249-5. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0249-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Schull J, Strote J, McGee K, Egnor R, Erb L. The uncertain response in the bottlenosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). J Exp Psychol Gen. 1995;124(4):391–408. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.124.4.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Shields WE, Washburn DA. Memory monitoring by animals and humans. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1998;127(3):227–250. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.127.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Shields WE, Washburn DA. The comparative psychology of uncertainty monitoring and metacognition. Behav and Brain Sci. 2003;26:317–374. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Washburn DA. Uncertainty monitoring and metacognition by animals. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sole LM, Shettleworth SJ, Bennett PJ. Uncertainty in pigeons. Psychon Bull & Review. 2003;10(3):738–745. doi: 10.3758/bf03196540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The Medial Temporal-Lobe Memory System. Science. 1991;253(5026):1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda-King C. Do orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) know when they do not remember? Anim Cogn. 2008;11(1):21–42. doi: 10.1007/s10071-007-0082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton JE, Shettleworth SJ. Memory without awareness: Pigeons do not show memory awareness in delayed matching to sample. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2008;34(2):266–282. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.34.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]