Abstract

Background

Ranolazine (Ran) is known to inhibit multiple targets, including: the late Na+ current, INa, the rapid delayed rectifying K+ current IKr, L-type Ca2+ current ICa,L, and fatty-acid metabolism. Functionally, Ran suppresses early afterdepolarization (EADs) and Torsade de Pointes (TdP) in drug-induced long QT type 2 (LQT2) presumably by decreasing intracellular [Na+]i and Ca2+ overload. However, simulations of EADs in LQT2 failed to predict their suppression by Ran.

Objectives

To elucidate the mechanism(s) whereby Ran alters cardiac action potentials (APs) and cytosolic Ca2+ transients (CaiT) and suppresses EADs and (TdP) in LQT2.

Methods

The known effects of Ran were inserted in simulations (Shannon and Mahajan models) of rabbit ventricular APs and CaiT in control and LQT2 models and compared to experimental optical mapping data from Langendorff rabbit hearts treated with E4031 (0.5 M) to block IKr. Direct effects of Ran on cardiac ryanodine receptors (RyR2) were investigated in single channels and changes in Ca2+-dependent high-affinity ryanodine binding.

Results

Ran (10µM) alone prolonged APDs (206±4.6 to 240±7.8 ms; p< 0.05); E4031 prolonged APDs (204±6 to 546±35 ms) and elicited EADs and TdP that were suppressed by Ran (10µM, n=7/7 hearts). Simulations (Shannon but not Mahajan model) closely reproduced experimental data except for EAD-suppression by Ran. Ran reduced Po of RyR2 (IC50=10±3µM; n=7) in bilayers and shifted EC50 for Ca2+-dependent ryanodine-binding from 0.42±0.02 to 0.64±0.02 M with 30 M Ran.

Conclusions

Ran reduces Po of RyR2, desensitizes Ca2+-dependent RyR2 activation and inhibits Cai oscillations which represents a novel mechanism for its suppression of EADs and TdP.

Introduction

Ran (2–6µM) is approved for the treatment of Angina Pectoris and ischemic heart disease but its exact therapeutic mode of action remains controversial. Early studies suggested that Ran altered myocardial energy metabolism by reducing fatty acid oxidation and glucose oxidation.1 The inhibition of fatty oxidation by Ran appeared at relatively high concentrations (12% inhibition at 100µM) which brought into question the validity of this mode of action.1–3 Alternatively, Ran at therapeutic doses (<10µM) was shown to inhibit the late sodium current, INa4. Besides its efficacy in the treatment of angina pectoris, Ran suppressed early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and Torsade de Pointes (TdP) in animal models of acquired long QT type 2 (LQT2)5 despite its tendency to prolong the QT interval by inhibiting the rapid, delayed rectifying K+ current, IKr.6

The inhibition of the INa window results in a decrease of intracellular Na+ and improved extrusion of Ca2+ via the Na-Ca exchange current, INCX.7–9 Inhibition of INa could account for the therapeutic effects of Ran because a reduced Cai load would reduce the bioenergetics stress, protect the heart from ischemic injury and suppress the incidence of EADs.

Two not mutually-exclusive mechanisms have been proposed to explain the generation of EADs. EADs could be elicited by the spontaneous re-activation of the L-type Ca2+ channels, ICa,L which is triggered by a “Ca2+ window current”, ICa,w during the AP plateau .10–14 At normal heart rates, APDs are too short to permit ICa,w but when the APD is prolonged as in LQT, there may be sufficient time to activate ICa,w.12 Agents that prolong APDs such as BAY-K8644 that increases the amplitude and duration of ICa,L13 or IKr blockers14 elicited a slow “conditioning phase” perhaps due to ICa,w followed by the faster EADs upstroke caused by a regenerative ICa,L.15 More compelling evidence has shifted the general consensus to Ca2+ overload as the primary trigger of EADs. In this case, long APDs result in a greater Ca2+ influx during the AP plateau phase, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+overload and spontaneous SR Ca2+ release where the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ activates the depolarizing, forward mode of INCX that re-activates ICa,L causing an EAD.16–18

Computational models for profiling proarrhythmic risk have made significant advances. Highly sophisticated in silico models have been developed to predict the shape and time-course of APs and CaiT in ventricular myocytes19, with the Shannon20 and the Mahajan21 models being specifically designed to incorporate experimentally determined properties of rabbit ventricular myocytes. The Shannon model contains a robust representation of excitation-contraction coupling where the properties of SR Ca2+ release include inactivation/adaptation and a non-linear dependence on SR Ca2+-load. The Mahajan model includes a minimal seven-state Markovian model of ICaL, which incorporates voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) and Ca-dependent inactivation (CDI). Both models include advanced calcium cycling kinetics, critical for the development of EADs.

Here, we show that modeling the actions of Ran based on its IC50 values at its known targets failed to predict Ran’s suppression of EADs in LQT2. We hypothesize that antiarrhythmic effect of Ran in the setting of LQT2 cannot be understood without including additional sites of action that alter intracellular Ca2+ handling and which to date have not been identified. The current study investigates the effect of Ran on the incidence of EADs and TdP in a rabbit model of acquired LQT2 using simultaneous optical mapping of APs and CaiT. Experimental findings are compared to mathematical simulations of APs and Cai in rabbit ventricular myocytes and tests the effects of Ran on RyR2 reconstituted in bilayers and Ca2+-dependent RyR2 activation by measuring changes in high-affinity [3H]ryanodine binding.

Materials and Methods

Heart Preparations and Optical Mapping

New Zealand White rabbits, (adult females >60 days old, ~2kg) were injected with pentobarbital (35 mg kg−1, I.V.) and heparin (200 U kg−1) via an ear vein; the heart was excised and retrogradely perfused through the aorta with Tyrode’s solution (in mM): 130 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.0 MgCl2, 4.0 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 50 dextrose, 1.25 CaCl2, at pH 7.4, gassed with 95% O2 and 5 % CO2. Temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 2 °C and perfusion pressure was adjusted to ~70 mmHg with a peristaltic pump.22 The atrio-ventricular node was ablated by cauterization to control rate (500–2000 ms). The heart was stained with a bolus of a voltage-sensitive dye (RH 237 or PGHI; 50µl of 1 mgml−1 in dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) and a Ca2+ indicator (Rhod-2/AM, 300µl of 1 mgml−1 in DMSO) delivered through the bubble trap, above the aortic cannula. The hearts were oriented to view the anterior surface, record control APs and CaiT then add E4031 (0.5µM) and/or Ran to the perfusate. E4031 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) and Ran was the kind gift of Dr. Luiz Belardinelli (Gilead Sciences, Palo Alto, CA). The optical apparatus based on 2 (16×16 pixels) photodiode arrays has been previously described.22, 23 Each pixel viewed a 0.9×0.9 mm2 area of myocardium and images were acquired at 1,000 frames/s.

Single channel recordings of Cardiac Ryanodine Receptors (RyR2)

Cardiac SR vesicles (5–10 g/ml) isolated from sheep ventricles24 were added to the cis-chamber of a planar bilayer setup containing 400 mM Cs+CH3O3S−, 25mM Hepes, pH 7.4, while the trans-side contained 40mM Cs+CH3O3S−, 25mM Hepes, pH 7.4. Bilayers were made of 5:3:2 PE:PS:PC (Avanti Polar Lipids – Coagulation reagent 1) painted across a 150 m hole separating two compartments. Following fusion of an SR vesicle to the bilayer, 4M Cs+CH3O3S−, 25mM Hepes, pH 7.4 was added to the trans-side to equalize the salt concentration at 400 mM. Channel output was filtered at 0.8–1.0 kHz and traces were recorded at a holding potential of −40 mV, for not less than three minutes following an addition of Ran to the cis-chamber. Single channel analysis was carried out using the ClampFit program (Axon Instruments: pClamp software). The Po (mean±SE) normalized to 1 (control without Ran) was plotted as a function of [Ran] (n=7).25

Ca2+ dependent ryanodine binding to RyR2

Equilibrium ryanodine-binding was measured as a function of free Ca2+ (Caf) in buffer containing 250mM KCl, 15mM NaCl, 2nM [3H]ryanodine, 13nM unlabeled ryanodine, 20mM PIPES, pH 7.1 ± 30 M Ran at an SR concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, following 3 hours incubation at 37°C.26 Nonspecific binding, measured in the presence of 200nM unlabeled ryanodine and 50 M Ca2+ +4 mM EGTA, was subtracted from all measurements. Ca2+ was buffered with EGTA and Caf was calculated with established binding constants and measured with a Ca2+-selective electrode.

Simulations

APs and CaiT predicted by the Shannon20 and Mahajan21 models were compared to optical recordings at various CLs (500, 1000, 2000 ms). The models were tested for their ability to generate EADs in a rabbit model of LQT2 (see supplement). Simulations of LQT2 included: a) a 50 % decrease of IKr, to mimic the effect of E4031, b) a 32% increase of ICa,L to mimic the increase in ICa,L expression measured in females hearts and shown to be a key factor for the higher risk of TdP in female hearts,27 c) an increase in cycle length to 1 or 2 s since bradycardia is a critical co-factor to promote EADs.

The multifaceted action of Ran was modeled by modifying the channel conductance based on the Hill equation using the following values: IKr (IC50=12µM), INa (IC50=5.9µM), ICa,L (IC50=50µM), and the sodium-calcium exchange current INCX (IC50=91µM),6 (See supplement). The code for Shannon model was provided by Dr. Jose Luis Puglisi (Davis, CA) and was compiled in Matlab, while the code for the Mahajan model was provided by Dr. Alain Karma (Boston, MA) and was compiled in C++.

Analysis

APDs, CaiT, rise-times, durations, amplitudes and Vm to Cai delays were measured at regular intervals. Measurements of duration are expressed as mean SEM; Student’s t –Test (paired) was applied to determine statistical significance based on p < 0.05.

Results

Effects of Ran on APs and CaiT before and after IKr block

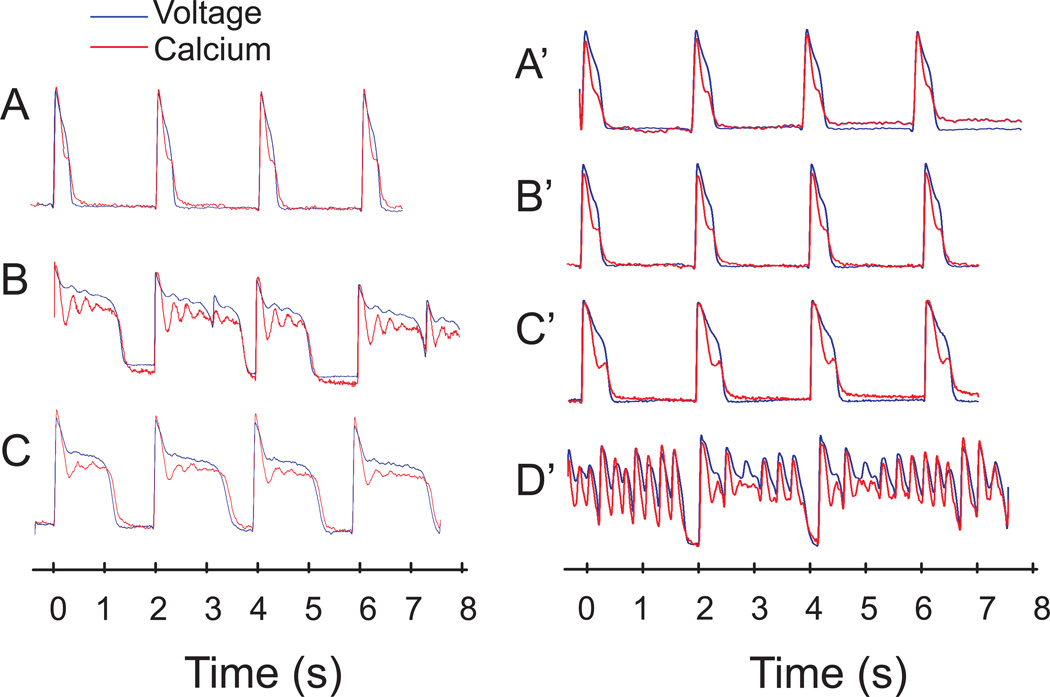

Figure 1 illustrates representative traces of optical APs and CaiT from the base of the left ventricle. Control recordings showed that CaiT followed the AP upstroke by 10 ms and recovered after the local repolarization (panel A). E4031 (0.5µM) added to the perfusate prolonged APD, induced CaiT oscillations and elicited EADs (panel B, n=7/7). The latter increased in frequency degenerating into salvos of EADs (< 10 min). However, perfusion with Ran (10µM) plus E4031 suppressed EADs within 5 min (panel C) and abolished the progressive worsening of the electrical instabilities to TdP. In panels A’ to D’, the order of addition of the two drugs was reversed; Ran (10µM) added alone prolonged APDs (204 6.1 to 240 7.8 ms; p < 0.05), CaiT (249 23.5 to 275 43.1 ms) and Cai rise-time (26 1.2 to 42 3.0 ms; p < 0.05) (compare A’ to B’). The subsequent addition of E4031 (0.5µM) failed to prolong APDs and to elicit EADs (panel C’). Ran was then washed out while keeping E4031 resulting in a marked APD prolongation, giving rise to EADs and TdP (panel D’). The washout of Ran exposed the proarrhythmic effect of E4031 and the protective effects of Ran. Table 1 summarizes the statistically significant effects of Ran and E4031 on APDs and CaiT.

Figure 1. Ran Suppresses EADs and TdP in LQT2.

Left Panel: Vm (blue) and Cai (red) measured from the same site at the base of the heart.

A: Control AP and CaiT with the heart was paced at 2 s CL

B: 10 min after E4031 (0.5µm)

C: 10 min after E4013 plus Ran (10µM)

Right Panel: The two drugs were added in the reverse order.

A’: Control, 15 min after Ran B’: 10 min after Ran plus E4031

C’: 5 min after washout of Ran but with E4031

D’: Washout of Ran prolonged APD and unmasked EADs due to the presence of E4031

Table 1.

Summary of Parameters

| APD (ms) |

CaiT Duration (ms) |

Vm-Cai delay (ms) |

CaiT Rise- Time (ms) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=8) | 204 6.1 | 249 23.5 | 6.3 0.7 | 26 1.2 |

| E4031 only (n=7) | 546 34.9* | 582 21.9* | 5.8 0.7 | 43 2.7* |

| Ranolazine only (n=6) | 240 7.8 * | 275 43.1 | 5.8 0.8 | 42 3.0* |

| E4031+Ranolazine (n=7) | 306 27.1*! | 343 51.0*! | 6.0 1.3 | 43 4.6* |

versus Control p <0.05; versus E4031 only p <0.05

Simulations

Selection of the model

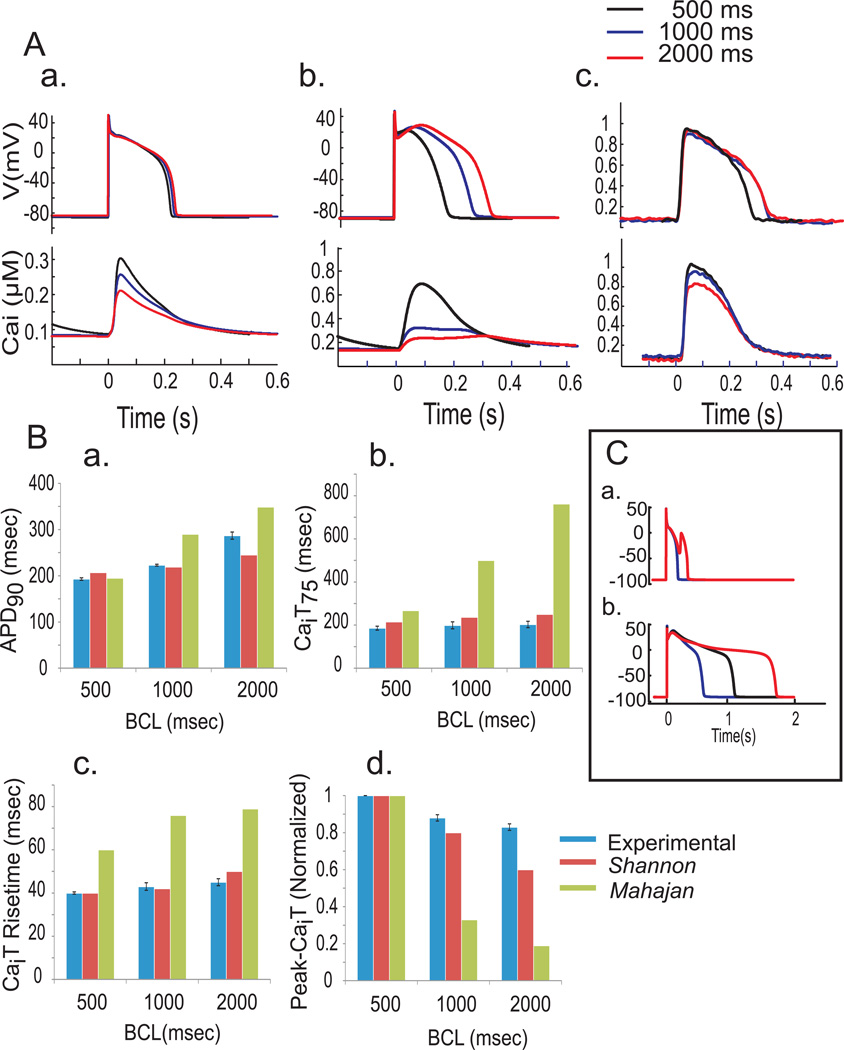

Figure 2A compares the APs and CaiT obtained with the Shannon (a) or Mahajan (b) model and the experimental data (c) at three different CLs (500, 1,000 and 2,000 ms). In Figure 2B, APD90, CaiTD75, Cai rise-time and Peak-CaiT amplitude were calculated and compared at the three CLs for the experimental data (blue bars), the Shannon (red bars) and the Mahajan (green bars) models. Based on quantitative comparisons, APD90 for the two models predicted closely the optical recordings at 500ms CL; but at 1,000ms CL, the Shannon was close but the Mahajan model deviated significantly predicting longer APD90 than optical APD90 and at 2,000 ms CL, the Shannon model underestimated and the Mahajan model overestimated the experimental APD90 (Fig. 2Ba). The duration of CaiT measured at 75% recovery to baseline, CaiTD75 were similar for the Shannon and experimental values but the Mahajan model deviated significantly, at all three CLs. Similarly, the Shannon and experimental values were considerably closer to each other than the values predicted by the Mahajan model for the rise time and peak of CaiT. For peak-CaiT the signals were normalized at 500 ms CL and changes in peak-CaiT were compared for the longer CLs. The Mahajan model predicted markedly slower rise-times and smaller peak-amplitudes of CaiT and rather abnormal shape and time courses of CaiT, particularly at longer CLs.

Figure 2. Comparison of mathematical models with experimental data.

A: APs (top) and CaiT (bottom) derived from Shannon (a) and Mahajan (b) models and optical signals from rabbit hearts (c) at different CLs (500 (black), 1,000 (blue) and 2,000 ms (red)).

B: Quantitative comparison of APD90 (a), CaiT75 (b), CaiT rise-time (c) and peak-CaiT (d) between mathematical models (Shannon, red; Mahajan, green) and experimental data (blue).

C: Predicted APs at 2 s CL by the Shannon model (a); control in blue and LQT2 in red and by the Mahajan model (b); control in blue and LQT2 in red. LQT2 simulation (see Methods) produced EADs with Shannon but not Mahajan.

The Shannon model generated EADs by inserting LQT2 simulations (see methods). However, the Mahajan model failed to generate EADs (Figure 2C). Based on the closer fit to experimental data and ability to generate EADs, we chose the Shannon model to simulate the actions of Ran.

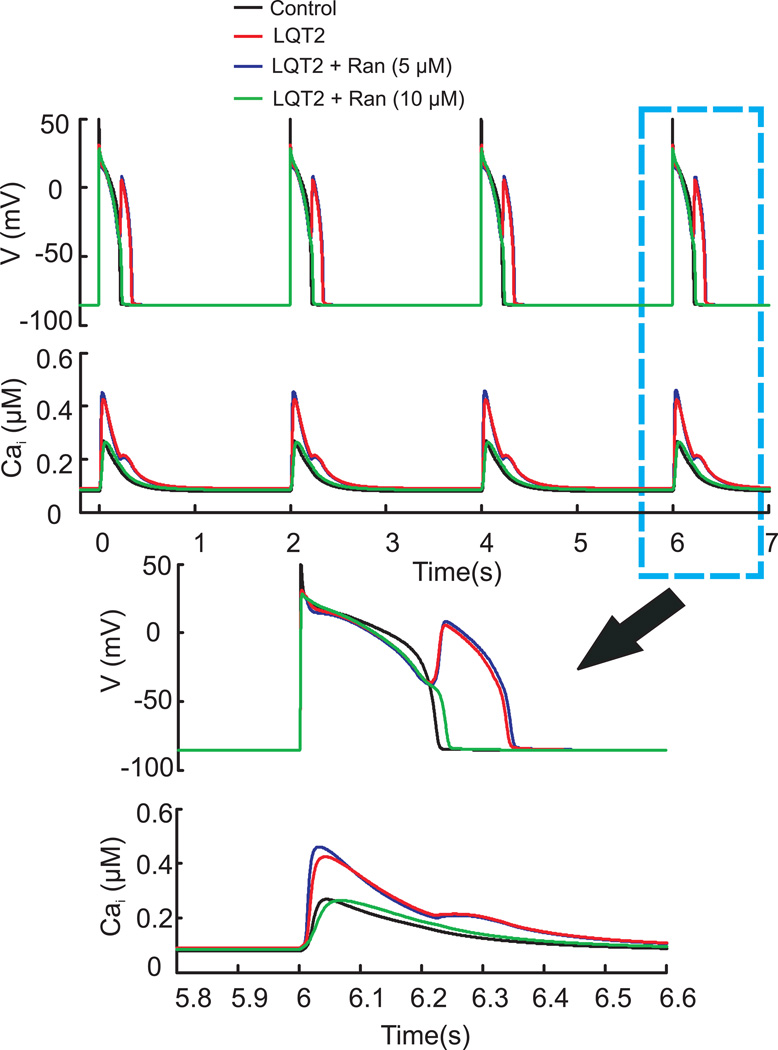

Simulation of the Actions of Ranolazine

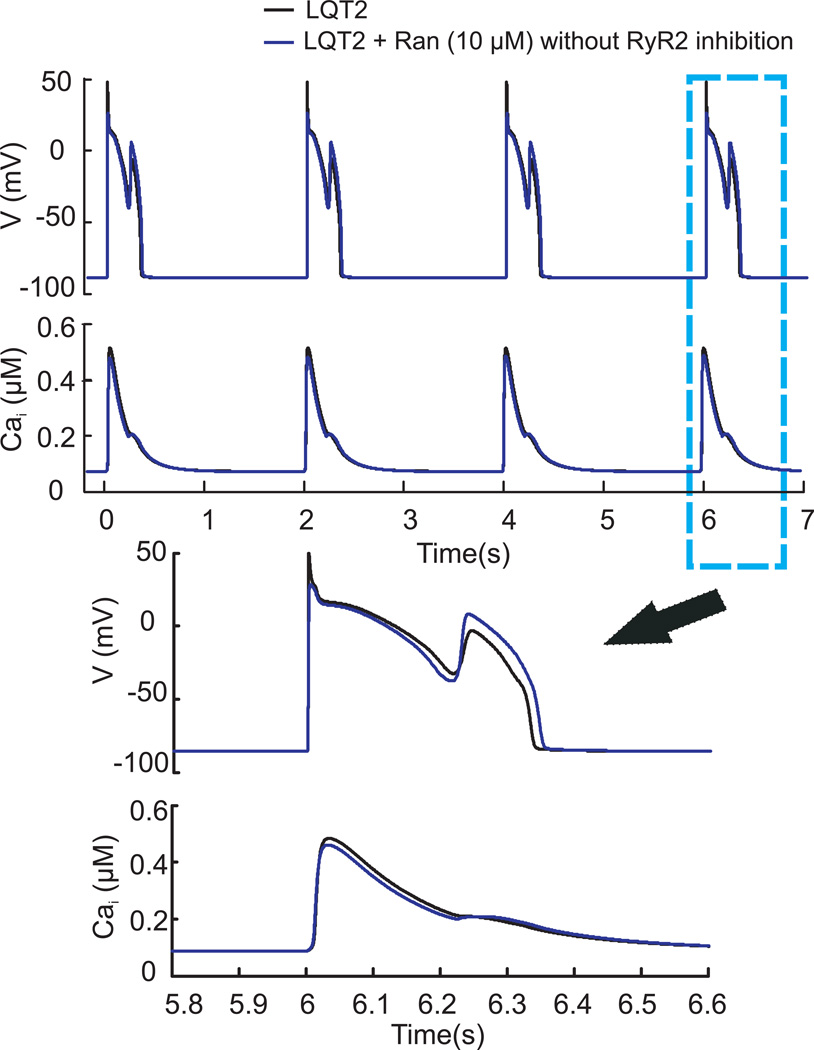

The effect of Ran was simulated based on its IC50 values on the major ionic currents.28 However, the model failed to predict the suppression of EADs by Ran (Figure 3), suggesting that our understanding of the actions of Ran was incomplete.

Figure 3. Simulation I - Antiarrhythmic effect of Ranolazine.

Steady state APs and CaiTs for the last four beats in a train of 75 pulses at 2 s CL under LQT2 condition (black); under LQT2 plus 10µM Ran (blue) as described in ‘Supplement’. Ran failed to suppress EADs.

Effects of Ranolazine on RyR2

Cardiac SR vesicles isolated from sheep ventricles were fused to planar bilayers and single channel open-probability (Po) was recorded in the presence of 50µM Ca2+ on the cis-side at pH 7.4. Figure 4A illustrates single channel recordings as a function of [Ran] from the same bilayer. Figure 4B plots the normalized Po (derived from 2 min of continuous recordings) as a function of [Ran]. The data were fit to a four parameter logistic curve (Sigma-Plot) which yielded an IC50 of RyR2 inhibition equal to 10±3µM (mean±SE, n=7). In figure 4C, equilibrium high-affinity ryanodine binding is plotted vs. [Ca2+] in the absence and presence of 30 M Ran. This data were fit to a Hill Plot. Ran shifts the EC50 for Ca2+ dependent activation of ryanodine binding from 0.42±0.02 to 0.64±0.02 µM, but has negligible effect on the degree of cooperativity (Hill number=2.5) or the maximum level of ryanodine binding. At 10 and 30 µM Ran, the Ca2+ dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding shifted to the right, respectively by 80 (not shown) and 220 (Figure 4C) nM Ca2+.

Figure 4. Effects of Ranolazine on Po of RyR2 and Ca2+-dependent [3H]ryanodine binding.

A: Characteristic single channel fluctuations following fusion of cardiac SR vesicles to a planar bilayer as a function of [Ran]. Po was measured in the presence of 50µM Ca2+ to maintain a highly active channel (i.e. Po ~0.5) and was averaged over 2 min of continuous recordings. c = closed, o = open state.

B: Normalized Po±SE vs. [Ran], n=7.

C: Ryanodine-binding vs. free [Ca2+] (Ca2+-selective electrode). Ryanodine binding was measured ± 30 M Ran with SR vesicles (0.5 mg/ml), data are average ± SE (n=4).

Simulations II

To fully simulate the effects of Ran, Po of RyR2 was modified vs. [Ran] according to single channel bilayer experiments, in addition to its other targets. The model correctly predicted experimental findings of Ran under normal and LQT2 condition.

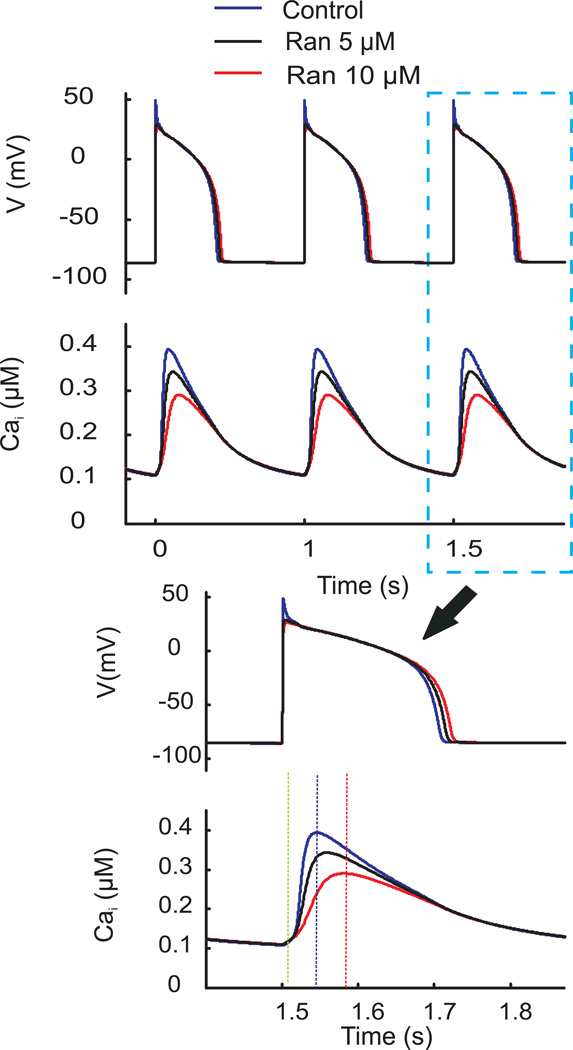

In controls (Figure 5), Ran at 5µM prolonged APD by 8ms and decreased peak-CaiT by 17%. While at 10µM, Ran prolonged APD by 15ms, increased CaiT rise-time by 1.9 fold and decreased peak-CaiT by 35% as previously reported.28 The simulation also predicts that Ran reduces the AP ‘notch’ most likely due to its effect of the late Na+ current but does not alter the voltage during the AP plateau phase. The effect of Ran on the notch is not detected by optical AP measurements because optical recordings smooth out the notch since they represent the sum of thousands of APs from myocytes under the field-of-view. In LQT2 (Figure 6), Ran (5µM) decreased Cai overload but was not effective at suppressing EADs. At 10µM, Ran suppressed EADs and reduced Cai overload, highlighting a concentration-dependent suppression of EADs.

Figure 5. Simulated effect of Ranolazine on APs and CaiTs.

Top traces: Steady state APs and CaiTs at 500 ms CL from the Shannon model at control (blue), 5µM (black) and 10µM (red) Ran. Bottom traces: APs and CaiTs shown at faster sweep speed.

Figure 6. Simulation II– Various [Ran] in LQT2 model.

APs and CaiTs from the Shannon model showing the last four beats from a train of 75 pulses at 2 s CL (black), with LQT2 (red), LQT2 plus 5µM Ran (blue) and LQT2 with 10µM Ran (green). EADs persisted with 5µM but not 10µM Ran.

Figure 7 investigates the mechanisms of action of Ran in LQT2 by testing its known effects, except for the inhibition of RyR2, and then including RyR2 inhibition. The stimulation demonstrates that RyR2 inhibition by Ran is required to suppress EADs.

Figure 7. Antiarrhythmic effect of Ranolazine when RyR2 is inhibited.

APs and CaiTs (Shannon model) showing the last four beats after 75 pulses at 2-s CL with LQT2 (black); with LQT2 and 10µM Ran but without (blue) and with RyR2 inhibition (red).

Discussion

The effects of Ran on the normal AP and its suppression of EADs in LQT2 hearts were readily reproduced using optical mapping. The main finding was that the Shannon model reproduced the experimentally measured AP and CaiT at various CLs and the initiation of EADs. However, the model failed to predict the suppression of EADs and TdP after inserting the currently known effects of Ran which contradicted experimental observations. Our data further shows that Ran reduced Po of RyR2 reconstituted in planar bilayers and desensitized RyR2 to Ca2+-dependent activation. Mathematical simulations that included changes in the Po of RyR2 caused by Ran, predicted the suppression of EADs indicating that the antiarrhythmic effects of Ran are dependent on its effect on RyR2. More precisely, the model required a reduction of Po of 50% (as would be expected by ~10µM Ran) along with the inhibition of INa to protect the heart from SR Ca2+ overload and to suppress EADs. At 10µM, Ran acts at multiple targets;28 and by inhibiting IKr, Ran prolongs APDs and QT intervals yet paradoxically does not induce but suppresses TdP in experimental LQT1-3 models9. Although Ran alone prolonged APDs, when added after E4031, Ran reduced APDs (Figure 1C). Moreover, when hearts were treated with Ran followed by E4031, Ran was considerably more effective at reducing E4031-induced APD prolongation (Figure 1C’). Although the final concentration of the two drugs is the same, the order of their addition produced different results. Electrophysiological studies of HERG channels expressed in HEK-293 cells indicated that Ran and E4031 shared the same binding domain to inhibit IKr but that Ran could not competitively displace E4031.29 Hence, there are two reasons why the two conditions differ. a) When E4031 is added first, Ran cannot displace E4031 but E4031 can displace Ran from HERG. b) E4031 causes Cai overload, oscillation, high plateau Cai and spontaneous SR Ca2+ release which activates INCX that prolongs APDs, Ran can reduce spontaneous SR Ca2+ release by stabilizing RyR2 but does not lower plateau Cai (Figure 1C) but when added first Ran inhibits the subsequent E4031-induced Cai overload (Figure 1C’) thereby reducing APD more effectively. In clinical studies, Ran lowered the incidence of arrhythmias in survivors of acute coronary syndrome30 and studies in patients with atrial fibrillation are promising.31 Ran has been found to alter Ca2+ handling by increasing the latency of Ca2+ waves and reducing the severity of SR Ca2+ overload in LQT3 induced by ATX-II32; an effect that would result in reduced likelihood of Ca2+ overload-induced triggered activity.

Mathematical simulation can provide a powerful tool to investigate the mechanisms of drug action but first it was necessary to select and validate the model based on experimental observation. The Shannon model produced APs and CaiT, which were close but not identical to the optical data; an important difference being the lack of APD prolongation with longer cycle lengths (Fig. 2A) which persisted with predictions of APD prolongation caused by Ran. The Mahajan model produced unrealistic CaiT at slower rates exhibiting a long rise-time to a first peak followed by a gradual rise of Cai before recovering to baseline (Fig. 2Ab). Also, the peak-CaiT collapsed compared at faster rates (Fig. 2Bd). Insertion of the effects of Ran in the Shannon model of LQT2 failed to predict Ran’s antiarrhythmic effect (Fig. 3).

There are precedents of drug with established ‘modes-of-action’ being re- discovered for new properties and/or sites-of-action. For instance, flecainide, a Class Ic antiarrhythmic known for its inhibition of the late INa was found to decrease the open-time of RyR2 channels and prevent spontaneous SR Ca2+-release in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.33 Similarly, Ran reduced Po of RyR2 with an IC50 of 10µM (Figure 4). The Shannon model predicts that RyR2 inhibition by Ran does not alter peak ICa,L but blunted ICa,L reactivation through a 27% reduction of INCX (−1.827 to −1.329 pA/pF) (See Figure 1 in Supplement). Hence, Ran inhibition of RyR2 primarily reduced INCX thereby suppressing EADs (as in Figure 7). Moreover, lower [Ran] (5µM) did not subdue EADs (Fig. 6) in agreement with previous findings.5 [Ran] subdues arrhythmias at ≥ 10µM but not when [Ran] falls below the concentration required for RyR2 inhibition. In support of this hypothesis, the MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial documented Ran’s antiarrhythmic efficacy at 10µM but not lower concentrations.30

Limitations: The Shannon model is based on ionic currents measured from rabbit and guinea pig (IKs) myocytes34 and the modulation of ionic currents by Ran was measured using guinea pig myocytes.6, 28 However, species-differences appear to be negligible because Ran has been shown to have similar antiarrhythmic properties in guinea pigs28, dogs5 and rabbits35.

In summary, our study applied computational techniques to discern discrepancies in the pharmaceutical actions of Ran which encouraged us to pursue alternative explanations. It allowed us to experimentally identify a new target and to confirm its validity. The findings show that in LQT2, Ran prevents excessive Ca2+ load by stabilizing RyR2 and desensitizing RyR2’s activation by Cai resulting in the suppression of EADs and TdP.

Supplementary Material

Key Words & Abbreviations

- Ran

Ranolazine

- APDs

Action potential durations

- CL

cycle length

- EADs

Early afterdepolarizations

- TdP

Torsade de Pointes

- LQT2

Long QT type 2

- Cai

intracellular free calcium

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- RyR2

Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor

- Po

open probability

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts to disclose

References

- 1.Clarke B, Wyatt KM, McCormack JG. Ranolazine increases active pyruvate dehydrogenase in perfused normoxic rat hearts: evidence for an indirect mechanism. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1996 Feb;28:341–350. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack JG, Barr RL, Wolff AA, Lopaschuk GD. Ranolazine stimulates glucose oxidation in normoxic, ischemic, and reperfused ischemic rat hearts. Circulation. 1996 Jan 1;93:135–142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabbah HN, Chandler MP, Mishima T, et al. Ranolazine, a partial fatty acid oxidation (pFOX) inhibitor, improves left ventricular function in dogs with chronic heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2002 Dec;8:416–422. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Li Y, Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004 Aug;310:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoons G, Oros A, Beekman JD, et al. Late na(+) current inhibition by ranolazine reduces torsades de pointes in the chronic atrioventricular block dog model. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010 Feb 23;55:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, et al. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004 Aug 24;110:904–910. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams J, Jones CA, Kirkpatrick P. Ranolazine. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2006 Jun;5:453–454. doi: 10.1038/nrd2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Fraser H. Inhibition of the late sodium current as a potential cardioprotective principle: effects of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine. Heart. 2006 Jul;92(Suppl 4):iv6–iv14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A, Sicouri S, Belardinelli L. Electrophysiologic basis for the antiarrhythmic actions of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2011 Aug;8:1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano Y, Moscucci A, January CT. Direct measurement of L-type Ca2+ window current in heart cells. Circulation Research. 1992 Mar;70:445–455. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.January CT, Moscucci A. Cellular mechanisms of early afterdepolarizations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992 Jan 27;644:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb30999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.January CT, Riddle JM. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circulation Research. 1989 May;64:977–990. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.January CT, Riddle JM, Salata JJ. A model for early afterdepolarizations: induction with the Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644. Circulation Research. 1988 Mar;62:563–571. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marban E, Robinson SW, Wier WG. Mechanisms of arrhythmogenic delayed and early afterdepolarizations in ferret ventricular muscle. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1986 Nov;78:1185–1192. doi: 10.1172/JCI112701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.January CT, Fozzard HA. Delayed afterdepolarizations in heart muscle: mechanisms and relevance. Pharmacol Rev. 1988 Sep;40:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemec J, Kim JJ, Gabris B, Salama G. Calcium oscillations and T-wave lability precede ventricular arrhythmias in acquired long QT type 2. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Nov;7:1686–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volders PG, Vos MA, Szabo B, et al. Progress in the understanding of cardiac early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes: time to revise current concepts. Cardiovasc Res. 2000 Jun;46:376–392. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi BR, Burton F, Salama G. Cytosolic Ca2+ triggers early afterdepolarizations and Torsade de Pointes in rabbit hearts with type 2 long QT syndrome. J Physiol. 2002 Sep 1;543:615–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bers DM, Puglisi JL. LabHEART: an interactive computer model of rabbit ventricular myocyte ion channels and Ca transport. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph Dec. 2001;281:C2049–C2060. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shannon TR, Wang F, Puglisi J, Weber C, Bers DM. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys J. 2004 Nov;87:3351–3371. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahajan A, Shiferaw Y, Sato D, et al. A rabbit ventricular action potential model replicating cardiac dynamics at rapid heart rates. Biophys J. 2008 Jan 15;94:392–410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi BR, Salama G. Simultaneous maps of optical action potentials and calcium transients in guinea-pig hearts: mechanisms underlying concordant alternans. J Physiol. 2000 Nov 15;529(Pt 1):171–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salama G, Hwang SM. Simultaneous optical mapping of intracellular free calcium and action potentials from Langendorff perfused hearts. Curr Protoc Cytom. 2009 Jul; doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy1217s49. Chapter 12: Unit 12 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meissner G, Henderson JS. Rapid calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles is dependent on Ca2+ and is modulated by Mg2+, adenine nucleotide, and calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 1987 Mar 5;262:3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Y, Yaeger D, Owen LJ, et al. Designing Calcium Release Channel inhibitors with Enhanced Electron Donor Properties: Stabilizing the Closed State of RyR1. Mol Pharmacol. 2011 Oct 11; doi: 10.1124/mol.111.074740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pessah IN, Stambuk RA, Casida JE. Ca2+-activated ryanodine binding: mechanisms of sensitivity and intensity modulation by Mg2+, caffeine, and adenine nucleotides. Mol Pharmacol. 1987 Mar;31:232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sims C, Reisenweber S, Viswanathan PC, Choi BR, Walker WH, Salama G. Sex, age, and regional differences in L-type calcium current are important determinants of arrhythmia phenotype in rabbit hearts with drug-induced long QT type 2. Circulation Research. 2008 May 9;102:E86–E100. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Wu L, et al. Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel antianginal agent. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Sep;9(Suppl 1):S65–S83. doi: 10.1177/107424840400900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Rapid kinetic interactions of ranolazine with HERG K+ current. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008 Jun;51:581–589. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181799690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow DA, Scirica BM, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Skene A, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Evaluation of a novel anti-ischemic agent in acute coronary syndromes: Design and rationale for the Metabolic Efficiency with Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (MERLIN)-TIMI 36 trial. Am Heart J. 2006 Aug;152:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murdock DK, Overton N, Kersten M, Kaliebe J, Devecchi F. The effect of ranolazine on maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with resistant atrial fibrillation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2008;8:175–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasserstrom JA, Sharma R, O'Toole MJ, et al. Ranolazine antagonizes the effects of increased late sodium current on intracellular calcium cycling in rat isolated intact heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 Nov;331:382–391. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilliard FA, Steele DS, Laver D, et al. Flecainide inhibits arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves by open state block of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels and reduction of Ca2+ spark mass. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2010 Feb;48:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viswanathan PC, Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Effects of IKr and IKs Heterogeneity on Action Potential Duration and Its Rate Dependence: A Simulation Study. Circulation. 1999 May 11;99:2466–2474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2466. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W-Q, Robertson C, Dhalla AK, Belardinelli L. Antitorsadogenic Effects of (±)-N-(2,6-Dimethyl-phenyl)-(4[2-hydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenoxy)propyl]-1- piperazine (Ranolazine) in Anesthetized Rabbits. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008 Jun 1;325:875–881. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.