Abstract

Background

Scratching an itch is perceived as being pleasurable. However, an analysis of topographical variations in itch intensity, the effectiveness of scratching to provide itch relief and the associated pleasurability has not been performed at different body sites.

Objective

To examine the role of scratching pleasurability in providing itch relief by investigating whether itch intensity is perceived differently at 3 different sites and to assess a potential correlation between the pleasurability and itch attenuation induced by scratching.

Methods

Itch was induced on the forearm, ankle and back using cowhage spicules in eighteen healthy subjects. These sites were subsequently scratched by an investigator with a cytology brush immediately following itch induction. The intensity of itch with and without scratching at these sites and the pleasurability of scratching were recorded by taking VAS ratings at 30 seconds intervals.

Results

Average itch intensity and scratching pleasurability ratings at the ankle and back were significantly higher than on the forearm. For the forearm and ankle, the higher the itch while scratching, the higher was the pleasurability. A higher baseline itch was linked to a higher itch reduction secondary to scratching in all tested areas. Pleasurability paralleled the curve of itch reduction for the back and forearm, however scratching pleasurability at the ankle remained elevated and only slightly decreased while itch was diminishing.

Conclusions

There are topographical differences in itch intensity, the effectiveness of scratching in relieving itch and the associated pleasurability. Experimental itch induced by cowhage was more intensely perceived at the ankle, while scratching attenuated itch most effectively on the back.

INTRODUCTION

Scratching is not only an effective means of relieving an itch, it is also often perceived as a highly pleasurable experience. The urge to scratch is particularly well-known to be hard to resist and is the driving force underlying the formation of the itch scratch-cycle, an addictive and vicious cycle. We have recently reported that ratings of scratching pleasurability in patients with atopic eczema are correlated to itch intensity ratings 1.

Currently, there is a paucity of psychophysical studies examining the pleasurability of scratching. In previous psychophysical studies examining itch, the forearm has been used predominantly as the typical site for itch induction, but much less is known about areas such as the back or the ankle, areas where patients with diseases such as lichen simplex chronicus or atopic eczema frequently itch and scratch. Indeed, the back is well-known as a preferred site for scratching, as proven by the multitude of back scratchers ubiquitous in many cultures for several centuries.

The goal of the current study was to examine the role of the pleasurability of scratching in providing relief for itch. We first evaluated whether itch intensity was perceived differently at different body sites and then we investigated the potential correlation between the pleasurability and the itch relief induced by scratching.

We used a visual analog scale to assess itch intensity, the pleasurability associated with scratching at forearm, ankle and back. Cowhage, rather than histamine, was selected as the pruritogen to induce experimental itch. Recent studies have suggested that cowhage-induced itch is a more reliable model for the experimental study of chronic itch 2,3 as cowhage acts on PAR2 receptors involved in the mediation of itch in AD and possibly in other dermatoses.

METHODS

Design overview

Itch was induced on the volar aspect of the forearm, the anterior side of the ankle region and on the back, approximately 5 cm laterally from the midline, under the scapula. In the next phase, the same sites were scratched with a cytology brush immediately following itch induction. The intensity of itch with and without scratching at these sites and the pleasurability of scratching were assessed. Experiments performed at different body sites were separated by a 10 minute interval.

Subjects

Eighteen healthy subjects (10 women, 8 men) 22–59 years of age participated in this study (average age 33.5 ±10.5). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFU Health Sciences). All volunteers provided written informed consent and were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Itch induction

Itch was evoked by the application of 40–45 cowhage spicules, which were counted under a magnifying lens and subsequently rubbed into the subject’s skin by a study investigator. The spicules were rubbed gently in a circular motion for 45 seconds within a 4 cm2 area of skin. Upon itch induction, the spicules were subsequently removed using adhesive tape (Scotch/3M, St. Paul, MN).

Psychophysical assessment of itch intensity and scratching pleasurability

Itch intensity (with and without scratching) and scratching pleasurability were assessed every 30 seconds for a duration of 5 minutes using a numerical VAS scale that was labeled from 0 (no itch) to 10 (maximum unbearable itch).

Passive scratching

Scratching was accomplished by a study investigator continuously moving a cytology brush in a linear direction (Medi-Pak 7-inch cytology brush 24–2199, General Medical Corporation, Elkridge, MD) over the itchy areas. Uniformity was controlled by applying sufficient pressure to bend skin-facing brush bristles, so that the brush handle touched the skin surface. The bending force of the cytology brush was equivalent to approximately 29g. The cytology brush includes approximately 1,000 individual bristles and the diameter of the brush is 7.5mm. Further, the same member of the research team applied the cytology brush for all subjects. Each examinee underwent a training session in which study personnel applied the cytology brush. The examinees were asked whether the procedure was similar to their experience when they scratch their skin themselves. All subjects reported that they perceived this procedure as closely simulating scratching. If any of the examinees perceived application of the cytology brush as a painful, scratching was ceased.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using PASW 18.0 software (SAS, Chicago, IL) with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Paired t-tests were performed to compare mean and peak VAS ratings of baseline itch, itch while scratching, and the pleasurability at the three sites (forearm, back, and ankle). The results were Bonferroni corrected. A Spearman correlation analysis was performed between ratings of itch intensity, the amplitude of itch reduction and pleasurability of scratching.

RESULTS

Regional variability in itch perception

Average and peak itch intensity at the forearm, ankle, and back are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1A. A comparison of cowhage-induced itch at these 3 sites reveals that the mean itch intensity rating at the ankle and back were significantly higher than at the forearm (p=0.002). No significant difference in itch intensity was found between the ankle and back.

Table 1.

Average and peak cowhage itch intensity reported at the three areas tested were measured on a numerical VAS scale of 0–10 (0= no itch; 10 =maximum unbearable itch) before and during scratching.

| Itch intensity VAS ratings (0–10) itch control | Ankle | Back | Forearm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (± SD) | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 3.8 ± 2.2 |

| Max (± SD) | 8.3 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 6.7 ± 2.3 |

| Itch intensity while scratching (VAS, 0–10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average (± SD) | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.95 | 1.9 ± 1.8 |

| Max (± SD) | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 2.5 | 4.3 ± 3.1 |

Figure 1.

Average itch intensity induced by cowhage in the absence of scratching (A), during scratching (B), and the pleasurability ratings of scratching, recorded simultaneously -with B- (C) at three sites: forearm, ankle, and back. Scratching reduced itch intensity and was paralleled by the pleasurability (ratings) curve.

Pleasurability of scratching

Significant differences in scratching pleasurability were noted among the different areas: the average scratching pleasurability ratings for the ankle and back were significantly higher than for the forearm, as shown in Figure 1C (p=0.02, p=0.007 respectively). There was no significant difference in scratching pleasurability between the ankle and back (Table 2). Age and gender differences had no effect on itch perception, scratching-itch modulation, or scratching pleasurability.

Table 2.

Mean and maximum scratching pleasurability as measured by a VAS during cowhage-induced itching in the three areas tested.

| VAS (0–10) | Ankle | Back | Forearm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mean ± SD) | 4.91 ± 2.81 | 4.64 ± 2.73 | 3.67 ± 2.51 |

| Max (mean ± SD) | 7.87 ± 1.92 | 7.06 ± 2.75 | 6.56 ± 3.08 |

The higher the itch ratings while scratching, the higher was the mean pleasurability rating at the forearm and ankle (p=0.038, 0.047; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient= 0.523, 0.52 respectively).

Scratching reduces itch intensity

Average itch intensity ratings were significantly reduced by scratching in comparison to control itch ratings with no scratching in all 3 areas tested as shown in Figure 1B (p=0.001, <0.001, and 0.001 in the ankle, back and forearm, respectively). The peak intensities of itch were also significantly reduced by scratching in all areas tested (p=0.001, <0.001, and <0.001 in the ankle, back and forearm respectively). Peak and average itch intensities while scratching are shown in Table 2.

A comparison of average itch intensities while scratching among the tested areas revealed that itch intensity on the back was significantly higher than on the forearm (p=0.009). No significant differences were noted between the ankle and back or ankle and forearm. The higher the mean baseline itch rating, the higher was the itch reduction secondary to scratching in all tested areas (p=0.042, <0.001, 0.001; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient= 0.513, 0.814, 0.746 for the forearm, ankle and back respectively). The average itch reduction was 3.59 ± 2.0, 3.05 ± 2.6, and 1.9 ± 1.8 in the ankle, back and forearm, respectively (Figure 2). Comparing the itch reduction in the three areas showed that itch relief in the ankle and back was significantly higher than on the forearm (p=0.005 and p=0.038, respectively).

Figure 2.

Average itch reduction in forearm, ankle and back due to scratching a cowhage induced itch. The highest itch reduction was in ankle, followed by the back and the forearm.

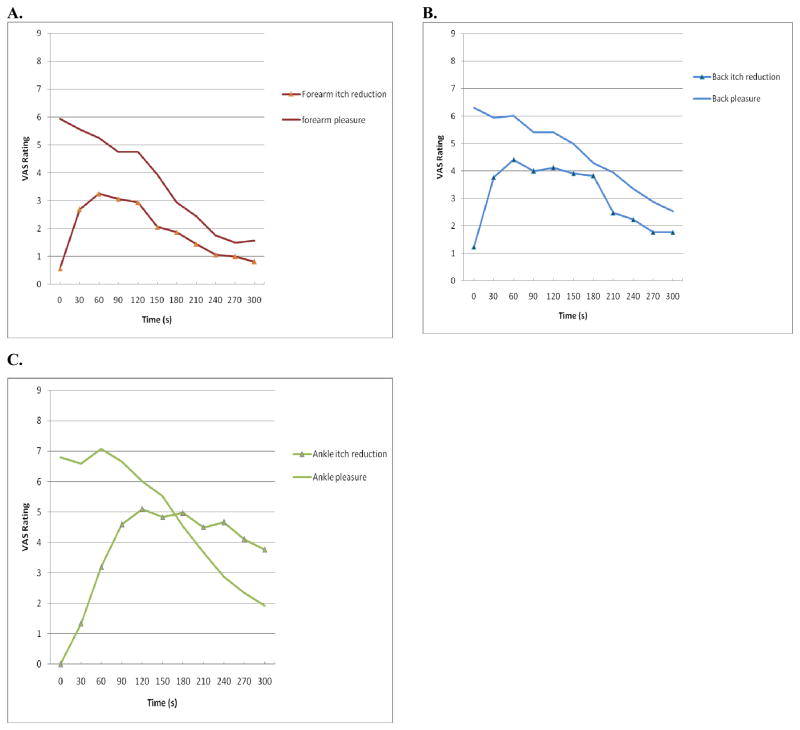

When itch reduction is plotted in the same graph with scratching pleasurability, a trend becomes apparent: ratings of pleasurability clearly parallel the curve of itch reduction for the back and forearm. In contrast, scratching pleasurability remains elevated at the ankle and only slightly decreases while itch is relieved. (Fig. 3: A, B, C).

Figure 3.

Itch reduction induced by scratching and scratching pleasurability plots over time follow a similar descending curve for back and forearm (A, B) while pleasurability remains slightly elevated while itch is relieved on the ankle (C).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show topographical differences in itch intensity, itch attenuation by scratching, and the associated pleasurability. Cowhage-induced itch was perceived most intensely at the ankle, while the attenuation of itch by scratching was most effective on the back. In both measurements, the intensity of perceived itch, as well as the magnitude of itch relief induced by scratching were less pronounced on the forearm compared to the other two sites.

Similarly, pleasurability reached higher amplitudes at the ankle, followed by the back and forearm. Interestingly, scratching on the back and forearm was found to attenuate cowhage-induced itch in a parallel fashion to the scratching pleasurability curve: the greater the itch ratings, the greater was the pleasurability of scratching. However, the pleasurability of scratching the ankle appears to be longer lived compared to the other two sites.

While we previously reported that pleasurability correlates with itch intensity in patients with atopic dermatitis1, topographic differences in perceived itch intensity have been seldomly reported. Topographical variations in itch perception have previously been reported by Shelley & Arthur, who noted remarkable differences in itch perception among various body areas in response to the insertion of a single cowhage spicule 4. In addition, Truini et al. found that the intensity of histamine-induced itch increased from face to foot, in opposite direction with the topographic variations in warmth and burning sensations 5. We could not directly compare these findings with ours, since we examined different body areas and moreover, we used cowhage as an itch inducer (cowhage releases mucunain which works via PAR2 receptors). Many factors could be envisioned to play a role in the topographical variations observed: 1) Nerve density. Skin biopsy studies have shown a regional variability in density of epidermal free nerve endings, which are higher in proximal, as opposed to distal (leg) sites 6–8. However, these findings do not explain why the ankle, which is the most distal of the sites examined, was the itchiest site. Interestingly, we also have previously shown nerve fiber dropout to be associated with lichen amyloidosis and nummular eczema, two chronic itchy dermatoses often located in the ankle (Maddison et al) 9–10.

In addition, spatial summation of itch information related to variations in the density of receptors may underlie differences in itch sensitivity. Spatial effects based on nociceptor density have been proposed for the sensation of warmth, cool, heat pain, and cold pain 11–15. There are also marked regional variations in the level of several neuropeptides that play a role in itch induction (substance P, CGRP)16. Regional or topographic differences in whole-body distribution of endo-cannobinoid and/or opioid receptors could also underlie regional differences in itch sensitivity and pleasurability of scratching.

It is also important to highlight the larger context of our findings in comparing differences between itch and pain transmission. While pain sensation is associated with a withdrawal (reflex), itch leads to a scratching response that is moreover pleasurable. However, scratching could also induce an algedonic response (characterized by the association of pleasure and pain) that could result in the inhibition of itch, according to the gate theory 17. Overall, itch seems to encompass more hedonic aspects that may vary topographically. An explanation for this contrast may lie in differences in central neuronal processing.

Itch relief induced by scratching is postulated to work via central nervous system suppression of itch processing 18. Andrew & Craig (2001) identified a population of spinothalamic tract (STT) neurons that responded to itch inducers 19. Davidson et al. have more recently shown (2009), that in primates, scratching the skin within the receptive field of STT neurons inhibited their firing rates during histamine-evoked activity 18. This mechanism suggests that scratching attenuates the spinothalamic transmission of itch, and therefore its subsequent perceptual and affective qualities. Scratching also activates brain areas that process itch sensation, while deactivating areas in the brain that are involved in the unpleasant sensation of itch, such as the anterior cingulate cortex20. Neuroimaging studies in healthy volunteers have shown that passive (artificial) scratching performed by an investigator, as well as the sensation of itch itself, evoke a strong activation of the putamen, which is not seen during passive scratching in the absence of itch 21. The putamen is a part of the dorsal striatum, which is involved in the anticipation of pleasure22. Of particular relevance to scratching behavior, Robbins & Everitt (1992) showed that dopamine in the dorsal striatum plays a role in the sensorimotor coordination of goal-directed consummatory behaviours and the initiation of an appropriate ‘response set’, such as the motor reparatory processes required for scratching 23

The peripheral nervous system may also play a powerful role in the relief of itch by scratching. Itch sensation is well-known to be mediated by a sub-population of cutaneous afferent C-fibers. Recent evidence indicates that the density of cutaneous C-fibers is linked to the perceived pleasantness of touch 24, 25. This latter observation builds on evidence that tactile pleasure is suggested to be mediated by a newly characterized mechano-sensitive cutaneous afferent C-fiber system – C-tactile afferents, or CTs; (McGlone & Spence 26). These factors may provide evidence for a peripheral nerve mechanism underpinning the reward basis of scratching itchy skin, in which C-tactile afferents provide the reward signals driving scratching behavior. It has also been suggested that a better known afferent C-fiber system – the C-nociceptors – inhibit itch neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Another possible mechanism for itch suppression by scratching could be related to a release of prostaglandin D2. Prostaglandin D2 was reported to play an inhibitory role against pruritus in an animal rodent model of atopic-dermatitis 27, but it has not been studied in relation to pleasurability and the applicability to humans remains to be proven.

The present study uncovers a topographical relationship between itch attenuation by scratching and the accompanying pleasurability in healthy individuals. Future studies could also examine the scratching pleasurability associated with other itchy areas such as the scalp28 or the anogenital region. It would also be clinically valuable to further examine topographical diferrences in chronic itch diseases where itch exhibits site predilections, such as atopic dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus or lichen amyloidosis.

What’s already known about this topic? The forearm has been used predominantly as the typical model for itch induction, but less is known about the back or the ankle, areas where lichen simplex chronicus or atopic eczema patients frequently itch and scratch. The pleasurability associated with scratching an itch at different sites has not been previously reported.

What does this study add? We evaluated topographical differences in itch perception induced with cowhage at three different body sites: forearm, ankle and back. We also investigated the effectiveness of scratching in providing itch relief at these sites in relationship with the accompanying pleasurability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIAMS (NIH) grant 5ARO155902-3.

References

- 1.O’Neill JL, Chan YH, Rapp SR, Yosipovitch G. Differences in Itch Characteristics Between Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis Patients: Results of a Web-based Questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:537–540. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papoiu ADP, Tey HL, Coghill RC, Wang H, Yosipovitch G. Cowhage-induced itch as an experimental model of pruritus. A comparison with histamine-induced itch. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosteletzky F, Namer B, Forster C, Handwerker HO. Impact of Scratching on Itch and Sympathetic Reflexes Induced by Cowhage (Mucuna pruriens) and Histamine. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:271–277. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelley W, Arthur R. The neurohistology and neurophysiology of the itch sensation in man. Arch Dermatol. 1957;76:296–323. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550210020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truini A, Leone C, Di Stefano G, et al. Topographical distribution of warmth, burning and itch sensations in healthy humans. Neurosci Lett. 2011;494:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimoto M, Arai I, Futaki N, et al. Putative mechanism of the itch–scratch circle: Repeated scratching decreases the cutaneous level of prostaglandin D2, a mediator that inhibits itching. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;76:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauria G, Holland N, Hauer P, et al. Epidermal innervation: changes with aging, topographic location, and in sensory neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 1999;164:172–178. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McArthur JC, Stocks EA, Hauer P, et al. Epidermal nerve fiber density: normative reference range and diagnostic efficiency. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1513–1520. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddison B, Namazi MR, Samuel LS, Sanchez J, Pichardo R, Stocks J, et al. Unexpected diminished innervation of epidermis and dermoepidermal junction in lichen amyloidosus. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:403–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddison B, Parsons A, Sangueza O, Sheehan DJ, Yosipovitch G. Retrospective study of intraepidermal nerve fiber distribution in biopsies of patients with nummular eczema. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:621–623. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181fe4c3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essick G, Guest S, Martinez E, et al. Site-dependent and subject-related variations in perioral thermal sensitivity. Somatosens Mot Res. 2004;21:159–175. doi: 10.1080/08990220400012414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens JC, Marks LE. Spatial summation of cold. Physiol Behav. 1979;22:541–547. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojo I, Pertovaara A. The effects of stimulus area and adaptation temperature on warm and heat pain thresholds in man. Int J Neurosci. 1987;32:875–880. doi: 10.3109/00207458709043342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglass DK, Carstens E, Watkins LR. Spatial summation in human pain perception. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1988;18:710. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglass DK, Carstens E, Watkins LR. Spatial summation in human thermal pain perception: comparison within and between dermatomes. Pain. 1992;50:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eedy DJ, Shaw C, Johnston CF, Buchanan KD. The regional distribution of neuropeptides in human skin as assessed by radioimmunoassay and high-performance liquid chromatography. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:463–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150(3699):971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson S, Zhang X, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler G., Jr Relief of itch by scratching: state dependent inhibition of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12(5):544–546. doi: 10.1038/nn.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrew D, Craig AD. Spinothalamic lamina I neurons selectively sensitive to histamine: a central neural pathway for itch. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:72–77. doi: 10.1038/82924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yosipovitch G, Ishiuji Y, Patel TS, et al. The brain processing of scratching. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1806–18011. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vierow V, Fukuoka M, Ikoma A, et al. Cerebral Representation of the Relief of Itch by Scratching. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:3216–3224. doi: 10.1152/jn.00207.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLean J, Brennan D, Wyper D, et al. Localization of regions of intense pleasure response evoked by soccer goals. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins T, Everitt B. Functions of dopamine in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Seminars in the Neurosciences. 1992;4:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison I, Löken LS, Minde J, et al. Reduced C-afferent fibre density affects perceived pleasantness and empathy for touch. Brain. 2011;134:1116–11126. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Löken LS, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F, Olausson H. Coding of pleasant touch by unmyelinated afferents in humans. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:547–548. doi: 10.1038/nn.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGlone F, Spence C. The cutaneous senses: Touch, temperature, pain/itch, and pleasure. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugimoto M, Arai I, Futaki N, et al. Putative mechanism of the itch–scratch circle: Repeated scratching decreases the cutaneous level of prostaglandin D2, a mediator that inhibits itching. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;76:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bin Saif GA, Ericson ME, Yosipovitch G. The itchy scalp - scratching for an explanation. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:959–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]