Abstract

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a T cell subpopulation that were named originally based on co-expression of receptors found on natural killer (NK) cells, cells of the innate immune system, and by T lymphocytes. The maturation and activation of NKT cells requires presentation of glycolipid antigens by CD1d, a cell surface protein distantly related to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-encoded antigen presenting molecules. This specificity distinguishes NKT cells from most CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which recognize peptides presented by MHC class I and class II molecules. The rapid secretion of a large amount of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines by activated NKT cells endows them with the ability to play a vital role in the host immune defense against various microbial infections. In this review, we summarize progress on identifying the sources of microbe-derived glycolipid antigens recognized by NKT cells and the biochemical basis for their recognition.

Keywords: microbial infection, immune responses, glycolipid antigens, CD1, NKT cells

Introduction

NKT cells have fascinated immunologists because they have a number of unique properties. First, mouse and human NKT cells carry out immediate, innate-like response that, in some circumstances, leads to the production of diverse cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-4, and TNF [1, 2]. Because of this vigorous cytokine production NKT cells have been reported to influence many types of immune responses and disease processes, particularly in mouse models [3–5]. Second, most NKT cells in mice express an invariant T cell antigen receptor (TCR) α chain and a homologous invariant α chain is found in many other mammalian species, including humans [1, 2, 6]. Because the TCR β chain is more variable, this TCR is sometimes described as being semi-invariant. Third, as noted, rather than recognizing peptides, NKT cells recognize glycolipids presented by a CD1d, a nonpolymorphic antigen-presenting molecule [5, 7, 8]. The trimolecular structures of the NKT T cell TCR bound to glycolipid-CD1d complexes have been solved, and these illustrate the structure of the CD1d-bound antigen, with the hydrophobic lipid buried in the CD1d antigen-binding groove. Despite this, the buried lipid still contributes to antigen recognition by positioning the sugar above the CD1d surface for the TCR.

Mouse and human NKT cells recognize essentially the same structures, but why has this specificity been conserved over 80 million years of evolution? Glycolipid antigens have been found in several pathogens, and NKT cell responses to these infectious agents are highly protective [5, 9, 10]. In agreement with others [11], we propose that the canonical or invariant TCR acts as a kind of pattern recognition receptor that recognizes widely expressed microbial glycolipids with α linked hexose sugars. Therefore, highly pathogenic bacteria with such glycolipid antigens may have driven the evolutionary conserved of the specificity of human and mouse NKT cells.

The CD1 family of antigen presenting molecules

In the battle of the mammalian immune system against invading pathogens, antigen presenting cells (APCs) must capture, process and present antigens to T lymphocytes. The classical antigen-presenting molecules, the highly polymorphic MHC class I and class II polypeptides, bind self or foreign peptides for presentation to CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, respectively [12–14]. A third family of antigen-presenting molecules, the CD1 family was first identified as a thymocyte antigen in 1979 and designated with the name CD1 in 1984 [15, 16]. These proteins are not highly polymorphic, and they present antigenic glycolipids to diverse T cell subpopulations, including CD4+, CD8+ and double-negative αβ T lymphocytes as well as δγ T cells [6, 17]. The CD1 family consists of four members that present glycolipids on the cell surface, CD1a-CD1d, which are divided into two groups according to the sequence identities of their antigen-binding α1 and α2 domains. CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c constitute group 1; CD1d is the only group 2 member. Humans and most other mammals have all of these CD1 proteins, while muridae rodents, including laboratory mice and rats, only have an ortholog of group 2 CD1d [5, 7, 8, 18]. CD1a, CD1b, CD1c, and CD1d are expressed predominantly by professional APCs, especially dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages and marginal zone B cells, as well as by thymocytes [15, 19–24], although expression of CD1d by other cell types, including hepatocytes and intestinal epithelial cells, has been reported. All CD1 proteins are type I integral membrane proteins, with a heavy chain consisting of extracellular α1 and α2 domains, which bind hydrophobic antigens, and a more membrane proximal α3 domains, which are immunoglobulin (Ig) super family homology units. The CD1 proteins are highly glycosylated polypeptides with the heavy chain non-covalently coupled with a light chain, β2-microglobulin, also a member of the Ig super family [25–28]. CD1e is fifth family member that is localized in lysosomes. CD1e facilities the processing and consequent loading of complex glycolipids onto other CD1 proteins [29].

In acidic endosomal and lysosomal compartments, CD1 molecules bind to glycolipid antigens. In some cases, the carbohydrate portions of these antigens are hydrolyzed to their antigenic form by specific glycosidases [30], and this form of antigen processing and CD1 loading is facilitated by lipid transfer proteins, such as CD1e and the saposins [31–34]. After arriving at the cell surface via exocytosis, CD1 molecules present antigens [30, 35]. During more than a decade of research, subpopulations of CD1-reactive T lymphocytes have been intensively investigated. T lymphocytes that recognize CD1a, CD1b and CD1c express TCRs with diverse combinations of α chain and β chains, and recent evidence suggests that some of these cells, such as those reactive to CD1a, are abundant in the peripheral blood of humans [36]. In addition to these lymphocytes, CD1 reactive T lymphocytes that express γδ TCRs also have been reported, particularly for recognition of CD1c [37].

NKT cells are reactive to CD1d

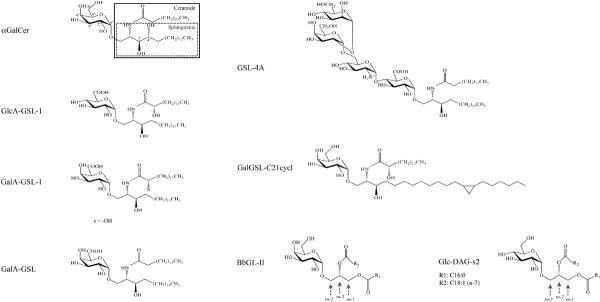

CD1d reactive T cells were defined as NKT cells because most cells of this population co-express NK cell makers, such as NK1.1, with their TCR [38]. However, it was found later that expression of NK cell markers is not the exclusive characteristic of this T subset, and not all cells in this subset uniformly express NK receptors [1, 2, 4, 39, 40]. The discovery of α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer) (Fig. 1), a synthetic, glycolipid antigen that can specifically stimulate the CD1d reactive T cells with the semi-invariant TCR, and the development of αGalCer loaded CD1d tetramers that bind to the semi-invariant TCR, greatly contributed to the unambiguous definition and identification of this T subset [40, 41]. These cells now are most often referred to as invariant NKT cells (iNKT cells), or type I NKT cells, to distinguish them from CD1d reactive T lymphocytes expressing diverse TCRs, called type II NKT cells [1, 2, 6, 42].

Fig. 1.

Structures of synthetic αGalCer and natural microbial lipid Ags. αGalcer has a galactosyl sugar head group and a ceramide (enclosd by a larger solid line box) lipid backbone containing a sphingosine base (enclosed in a dot line internal box), connected by a 1–1' α linkage. The lipid moiety of B. burgdorferi Ag BbGL-II is a diacylglycerol, containing two fatty acid chains, R1 and R2, which are described in Table 1. GlcA-GSL-1, GalA-GSL-1, GSL-4A, and BbGL-II are the names given to purified antigens, which in some cases have heterogeneity.

iNKT cells exhibit an antigen experienced or memory phenotype. They are further activated when their TCR recognizes glycolipid antigens presented by CD1d, by the synergistic stimulation by glycolipid antigens and cytokines, particularly IL-12, or even by cytokines alone [43–46]. iNKT cells are striking because a single cell is able to secrete a large amount of Th1 and Th2 cytokines rapidly after stimulation, consequently activating and influencing various immune cells [47–51]. Therefore, although iNKT cells account for a relatively small portion of total T lymphocytes, <1%, they play a critical role in amplifying innate immune responses against infectious pathogens and they provide a bridge linking innate immunity to acquired immunity [3, 4]. In mouse models, iNKT cells are involved in the surveillance for tumors, the prevention of autoimmune diseases, the clearance of viral and bacterial pathogens [10, 52–55], and they participate in various inflammatory reactions such as ischemia reperfusion injury, ozone-induced asthma, and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [56–59]. Furthermore, various human diseases have been correlated with reduced iNKT cell number or altered function [60, 61]. Herein, we provide an overview focusing on the sources of bacterial glycolipid antigens, their structure and presentation by CD1d, and the biochemical basis for their induction of iNKT cell activation.

Synthetic antigens for iNKT cells

In 1994, in a screen of marine sponge glycolipids for their anti-tumor activity, Natori et al. identified agelasphins derived from the marine sponge Agelas mauritianus as novel antitumor and immunostimulatory cerebrosides [62]. Later, some minor structural modifications on the agelasphins were performed that produced α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), commercially designated as KRN7000 (Fig. 1). αGalCer possesses a ceramide backbone comprised of a C18 phytosphingosine with hydroxyl groups at the 3' and 4' carbon positions, and a C26 fatty acid chain. The ceramide lipid was conjugated to a single galactose carbohydrate head group via an α-anomeric linkage (Fig. 1). In 1997, Kawano et al. identified αGalCer as an exceptionally potent ligand for iNKT cells. Surface plasmon resonance studies have documented the unusually strong affinity of the semi-invariant TCR for αGalCer/CD1d complexes, measured in the 11–350 nM range [63–68]. A striking characteristic of αGalCer is the α-anomeric linkage between the ceramide moiety and the carbohydrate head group, given that mammalian cells only synthesize β-linked glycolipids. The α-linkage is critical for the potent antigenic activity of αGalCer because the β-anomeric isomer (βGalCer) was not able to stimulate iNKT cells or stimulated them only weakly [69].

A number of studies have probed structural variants of αGalCer in order to understand the biochemical basis for the extraordinarily high affinity of the semi-invariant TCR. Not surprisingly, the sugar protruding from the CD1d groove plays a major role in determining TCR affinity. Substitution of glucose for galactose reduced iNKT cell TCR affinity by approximately 10-fold [65, 68], and substitution to mannose completely abrogated the stimulation of iNKT cells [41, 65]. On the galactose sugar, all modifications of the 2" hydroxyl group of the sugar (Fig.1) that were tested abrogated the antigenic activity of αGalCer, while modifications of the 3" or 4" hydroxyl groups were more tolerated, although they did reduce antigenic potency to some extent [70–72] as well as having effects on TCR affinity [68]. The 6"-position, by contrast, can accommodate a number of chemical modifications without a requirement for lysosomal antigen processing to remove the modifications for recognition by the semi-invariant TCR [30, 73].

In addition to the carbohydrate moiety, the lipid backbone buried in the CD1d antigen binding groove also contributes to the antigenic potency. Removal of both 3' and 4'-hydroxyl groups on the phytosphingosine base resulted in the complete loss of activity for the compound [74–78], while removal of the 4'-hydroxyl alone led to some loss of antigenic potency and a reduced TCR affinity [65, 68, 74]. Truncation of the lipid chains, either the phytosphingosine base or the fatty acid, also reduced the ability of the compound to stimulate iNKT cells [75].

Although the α-linkage of the sugar is required for a high degree of antigenic potency, several recent reports show that ceramide containing antigens with β-linked sugars, also can be recognized although they are weaker antigens. For βGalCer and isoglobotrihexosylceramide, structural studies show that TCR binding apparently squashes the sugar down so it is in close to an α conformation more parallel to the top of the CD1d molecule [79, 80]. It is surprising, however, that recent studies reported that β-glucosylceramide is a potent self-antigen, and that β-mannosylceramide is a novel iNKT cell agonist that induces a potent anti-tumor response in vivo that is dominated by TNF secretion [81, 82]. The structural basis for the recognition of these latter two β-linked glycosphingolipid (GSL) antigens by the semi-invariant TCR remains to be determined.

Glycosphingolipid antigens derived from Sphingomonas bacteria

The first chemically well-defined microbial antigens that activate iNKT cells were obtained from Sphingomonas ssp., which are Gram-negative bacteria widely distributed in nature, especially in water and soil. Sphingomonas may be commensal organisms in the intestines of mice and some humans [83, 84] and although these bacterial species usually are not human pathogens, they have been implicated in causing a number of nosocomial and community-acquired infections, for example, bacteremia, meningitis and peritonitis [83, 85–87]. It also was proposed that these bacteria could contribute to the cause of primary biliary cirrhosis, an autoimmune disease leading to small bile duct damage. According to these studies, Sphingomonas infection induced antibodies against the microbial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E2 enzyme that are cross-reactive with the host mitochondrial counterparts as well as inducing chronic T-cell mediated autoimmunity [83, 88]. Also, in another mouse disease model, administration of a Sphingomonas derived synthetic glycolipid antigen rapidly induced airway hyperreactivity by activating iNKT cells [89], although there is no evidence yet that bacterial infection would lead to the same outcome.

Of Gram-negative bacteria, Sphingomonas are different because they do not express lipopolysaccharide (LPS), but instead employ GSLs to construct their cell walls. The main GSL components of these cell walls are heterogenous GSLs that include α-glucuronosyl-ceramide, α-galacturonosylceramide and GSLs with more complex carbohydrates containing up to four saccharide units, in addition to variations in the ceramide lipid [90–92]. Mattner and co-workers using both purified material from Sphingomonas capsulata and synthetic material based on this, and Kinjo and colleagues taking a similar path with materials from Sphingomonas paucimobilis and Sphingomonas yanoikuyae, identified the main glycolipid antigens that stimulate iNKT cells [93, 94]. Almost at the same time, Sriram et al. found crude glycolipid extracts from S. paucimobilis were able to activate several iNKT cell hybridomas [95]. The GSLs purified from these Sphingomonas strains have minimal variations in structure, with a glucuronic acid (GlcA) sugar in S. paucimobilis to form GlcA-GSL-1 and a mixture of glucuronic and galacturonic acids (GalA, to form GalA-GSL-1) in S. yanoikuyae (Fig. 1). All of these antigens, however, have an α-linkage to connect the carbohydrate to the ceramide [93]. CD1d tetramers loaded with the Sphingomonas compounds identified the iNKT cell population in wild type splenocytes or liver mononuclear cells, but cells were not stained from Jα18−/− mice, which cannot form the invariant TCR α chain because of a deficiency for the required Jα segment. Furthermore, CD1d deficient or Jα18−/− mice had a significantly higher burden of bacteria at early times after Sphingomonas infection, pointing to a defect in bacterial clearance due to the absence of iNKT cells [93, 94].

While monosaccharide-containing GSLs are the main glycolipid components of the cell walls of Sphingomonas species, they are not the only ones. Not only do different strains express distinct GSL profiles, but also according to the environmental conditions these bacteria are able to synthesize various GSLs with mono- or oligo- saccharides linked to ceramides consisting of different sphingosine bases [90–92]. Sphingomonas GSLs with more complex carbohydrate head groups include trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide glycosylceramides, originally designated as GSL-3 and GSL-4 respectively (Fig. 1). Both of these compounds contain glucuronic acid linked to the lipid. The antigenic activity of the GSL-4 variants for iNKT cells were found to be not detectable or very weak, probably because mammalian APCs do not have glycosidases that can degrade the carbohydrate head groups to a monosaccharide form containing glucuronic acid [96, 97]. However, it is notable that a variant designated as GSL-4A (Fig. 1), comprised of a tandem tetrasaccharide of α-mannose(1–2)α-galactose(1–6)α-glucosamine(1–4)α-glucuronosyl linked to a ceramide with an α-anomeric conformation, not only was able to stimulate iNKT cells, although to a lesser extent compared with than a synthetic Sphingomonas-based antigen GlcA-GSL, but also did not require lysosomal processing to trim the relatively complex oligosaccharide head group.

Besides variations in the sugar, the sphingosine chains of Sphingomonas bacterial GSLs also vary in the length and unsaturation, including a C18:0, C20:1 and a cyclopropyl-C21:0 [90, 92, 98, 99]. A synthetic GSL with a single galactosyl group and a cyclopropyl-C21:0 sphingosine chain, named as GalGSL-C21cycl (Fig. 1), showed antigenic activity intermediate between GalA-GSL and αGalCer, which further confirms the previous conclusion that the hydrophobic glycolipid backbone also contributes to the ability of glycolipid antigens to activate iNKT cells.

The synthetic GalA-GSL comound (Fig. 1) was analyzed in an X-ray crystallographic structural study for its interactions with CD1d and in a trimolecular complex with CD1d and the semi-invariant TCR. One important difference distinguishing GalA-GSL from αGalCer is the sugar moiety, as the 6'-OH in galactose is substituted with a carboxylate in GalA-GSL. This compound also has a much shorter fatty acyl chain composed, of only 14 carbons versus 26 carbons for αGalCer, and the GalA-GSL sphingosine lacks the 4'-OH of the phytosphingosine of αGalCer. The hydrophobic CD1d binding groove has two large pockets, designated A' and F' [100]. Analysis of the crystal structure of the GalA-GSL-CD1d complex showed that similar to the αGalCer complex, the fatty acyl chain of the antigen inserted into the A' pocket of CD1d with the sphingosine chain in the F' pocket and the sugar head group protruded from the center of the binding groove at the CD1d surface [101]. However, lack of the 4'-OH led to a lower orientation of sphingosine in the pocket in order to make optimal hydrogen bonds with Asp at CD1d position 80, which resulted in GalA-GSL more deeply inserted into the CD1d groove. Moreover, the hydrogen bond between Arg-79 and the 3'-OH in the αGalCer-CD1d complex was lost, and therefore Arg-79 orients differently and may interfere partially with the interaction between CD1d and the TCR. A shortened fatty acyl chain was not able to fully occupy the A' pocket, and a so-called spacer lipid, a fatty acid with 16 carbons, also bound in this pocket and presumably stabilized the GalA-GSL-CD1d complex. Overall, these structural alternations caused the galacturonosyl group of GalA-GSL to shift laterally compared with the galactosyl group of αGalCer in the complex with CD1d [101]. There were no hydrogen bonds linking the 6'-COOH in the galacturonic head group to CD1dconsistent with the ability of this sugar position to tolerate variation in chemical structure [101].

Glycophospholipid antigens derived from Borrelia species

Borrelia spp. are Gram-negative spirochetes that do not express LPS in their cell wall. Twelve of the 36 known species are able to cause Lyme disease, also called borreliosis, a zoonotic, vector-borne illness transmitted by the bite of infected ticks. According to a report from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of this disease is 7.9 cases out of 100,000 persons and the number of reported cases has been increasing, making it the most common vector borne disease in the United States. In North America, B. burgdorferi is the predominant one of the three major Borrelia species that cause Lyme disease. Several Borrelia strains, including B. hermsii, B. parkeri, and B. recurrentis, can cause relapsing fever, often together with severe bacteremia.

CD1d deficiency rendered mice that are highly resistant to Borrelia susceptible to arthritis, a principal disease manifestation in the mouse model of Lyme disease [102], suggesting a role for iNKT cells in host protection. Compared with wild-type mice, after infection CD1d−/− mice had a dramatically increased level of spirochete DNA in tissues and a higher titer of Borrelia specific IgG2a in serum, the increased IgG2a might reflect an increased bacterial load in the absence of iNKT cells. A subsequent study analyzed the role of splenic marginal zone B (MZB) cells that express the highest amount of CD1d level [103] on the clearance of Borrelia bacteria. It was found that MZB cells secreted Borrelia specific IgM and helped to reduce bacterial load in wild-type mice by 24 hours post-infection, whereas by 96 hours the MZB cells in CD1d knockout mice only produced minimal pathogen-specific IgM and the bacterial burden remained elevated [104]. CD1d has multiple functions, however, as it activates type II as well as type I NKT cells, and potentially it could have other roles. Tupin et al. therefore analyzed Jα18−/− mice to demonstrate the involvement of iNKT cells in the clearance of Borrelia bacteria more directly. They showed increased joint inflammation and effects on spirochete clearance in BALB/c background Jα18−/− mice [105]. They also demonstrated iNKT cell activation in vivo, including the secretion of cytokines, at one week after infection. In a subsequent study, bacterial load in the joints was increased 25-fold at day 3 in the absence of iNKT cells, and following infection, alteration in iNKT cell migration in the liver sinusoids and interactions with Kuppfer cells, liver macrophages, were visualized by intravital microscopy [106]. In C57BL/6 mice, however, there was increased carditis more prominently than arthritis in the absence of iNKT cells, as well as evidence for a local accumulation of iNKT cells in the heart and increased local IFN-γ [107].

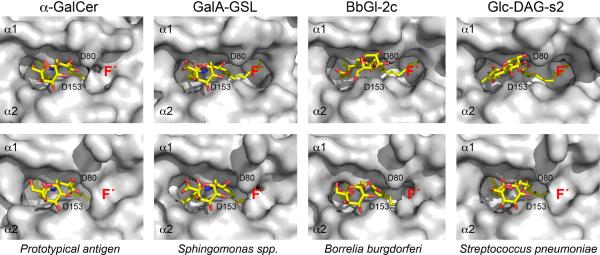

Analytical chemistry was required in order to determine if B. burgdorferi has a glycolipid antigen that can activate iNKT cells. There are two major glycolipids in this pathogen. One of these, designated as B. burgdorferi glycolipid 1 (BbGL-I), is a cholesteryl 6-O-acyl-β-galactoside, and it accounts for about 23% of the total glycolipids. A second one, BbGL-II (Fig. 1 and Table 1), is a 1,2-diacyl-3-O-α-galactosyl-sn-glycerol, accounting for approximately 12% of the total glycolipids [108]. When plated on the microwells pre-coated with purified mouse CD1d protein, the diacylglycerol (DAG)-containing BbGL-II, but not BbGL-I, was able to stimulate iNKT cell hybridomas to secrete IL-2, indicative of TCR engagement. Natural BbGL-II is a mixture of glyco-DAG compounds with C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C18:1 and C18:2 fatty acid chains, with C16:0 and C18:1 as the most abundant ones (Table 1). Based on this, eight BbGL-II compounds comprised of different combination of C16:0, C18:1, and C18:2 fatty acids were synthesized and their antigenic activity was determined. A compound designated as BbGL-IIc, with a C18:1 oleic acid in the sn-1 position and C16:0 in the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone, was the optimal one for stimulating mouse iNKT cells. BbGL-IIf, by contrast, with the C18:1 fatty acid in the sn-2 position, could bind to mouse CD1d but was not antigenic. Structural analysis showed that the two compounds bound to CD1d differently. BbGL-IIc could be accommodated by mouse CD1d with the kinked sn-1 oleoyl chain, caused by a cis double bond at the nine position, inserted into A' pocket, while the saturated C16:0 palmitoyl chain resided in the F' pocket (Fig. 2). This permitted the formation of polar interactions between the galactosyl head group of BbGL-IIc and the amino acids Asp153 and Thr156 in the CD1d α2-helix, similar to that of αGalCer. However, different from αGalCer, there were no hydrogen bonds between Arg-79 or Asp-80 with BbGL-IIc because of the different structures of the diacylglycerol and ceramide backbones [109]. In the case of BbGL-IIf, the C18:1 oleic acid also was bound to the A' pocket of CD1d, but since in BbGL-IIf this fatty acid is in the sn-2 rather than the sn-1 position, the galactose sugar protruding from the top of CD1d was oriented differently and in a suboptimal position compared to the BbGL-IIc-CD1d complex. This illustrates a more general property of the two major classes of microbial glycolipid antigens. Glycosphingolipids are bound tightly in a single orientation with the sphingoid base in the F' pocket due to a network of hydrogen bonds that hold this category of glycolipids rigidly in place. The DAG containing antigens, by contrast, have reduced hydrogen binding and therefore can bind more flexibly in two orientations [110].

Table 1.

Fatty acid components of synthetic BbGL-II compounds

| BbGL-II compounds | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| BbGL-IIa | C16:0 | C18:1 |

| BbGL-IIb | C16:0 | C18:2 |

| BbGL-IIc | C18:1 | C16:0 |

| BbGL-IId | C18:1 | C18:2 |

| BbGL-IIe | C18:2 | C16:0 |

| BbGL-IIf | C18:2 | C18:1 |

| BbGL-IIg | C16:0 | C18:0 |

| BbGL-IIh | C16:0 | C16:0 |

R1 and R2 represent sn-1 and sn-2 positions of glycerol, respectively (Fig. 1). The length of fatty acyl chains and the number of unsaturated bonds are indicated.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of αGalCer, GalA-GSL, BbGL-IIc, and Glc-DAG-s2 binding to mCD1d before and after TCR engagement. (Top) Glycolipid ligand presentation shown in “TCR view” before TCR binding. Note how the galactose of BbGL-IIc and the glucose of Glc-DAG-s2 lose intimate contacts with α2-helix of mouse CD1d but instead rotate counter-clockwise (~60°) toward Asp80 (D80) of α1-helix, in contrast to αGalCer. (Bottom) Glycolipid bound in the TCR containing ternary complexes shown in the same view as the top, but with the bound TCR removed for clarity. Note that the TCR forces both the galactose of BbGL-IIc as well as the glucose of Glc-DAG-s2 into a position similar to that of αGalCer and GalA GSL before TCR engagement. This structural change induced upon TCR binding is necessary to allow for the conserved TCR binding footprint on CD1d. Also, note how the TCR is able to induce the formation of the F' roof in all CD1d-glycolipid complexes that do not have a preformed F' roof (e.g. αGalCer, top panel).

Glycolipids from Gram-positive pathogensalso engage the semi-invariant TCR

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae, also known as pneumococcus) is an agent of pneumonia, bloodstream infections and meningitis in children and the elderly. Neurologic sequelae and/or learning disabilities can occur in meningitis patients. Hearing impairment can result from recurrent otitis media, now estimated to cause 11% of all deaths in children from 1 month to 5 years of age [111]. Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is a cause of life-threatening bacterial infections such as sepsis and meningitis in human newborns. Both of these Gram-positive pathogens have antigens that activate iNKT cells. We focused on S. pneumoniae because mice lacking iNKT cells previously were shown to be highly sensitive to intratracheal infection with these bacteria [112, 113]. The previous work showed that during an infection with S. pneumoniae, IFN-γ derived from liver mononuclear cells, likely iNKT cells, plays a role in clearance through stimulating increased production of TNF-α and MIP-2, which recruits neutrophils to the lung by 12 h [112]. Subsequent research showed more directly that iNKT were activated in an antigen-dependent fashion nearly immediately following infection. iNKT cells in the lungs of mice infected with S. pneumonia expressed IFN-γ and IL-17 by 13 hours, and treatment with a CD1d blocking antibody substantially reduced IFN-γ production and caused a higher bacterial burden in the lung. Furthermore, dendritic cells (DCs) from taken directly infected mice could activate iNKT cell hybridomas in vitro to secrete IL-2, indicating that the DC presented an antigen that could activate iNKT cells.

Biochemical evidence for a glycolipid antigen in S. pneumoniae was first obtained from iNKT cell hybridomas that were activated by CD1d coated plates exposed to total bacterial sonicates in a cell free antigen presentation assay. Subsequent analyses demonstrated that the major antigen in S. pneumoniae and GBS contained a glucose as opposed to a galactose sugar α-linked to the sn-3 position of a DAG antigen with palmitic acid (C16:0) in sn-1 and cis-vaccenic acid (C18:1, n-7) linked at sn-2 (Fig. 2) [114]. This single species, which we refer to as S. pneumoniae glucosylated diacylglycerol (SPN Glc-DAG) consisted of up to 43% of the total glycolipid of some S. pneumoniae strains. Analysis of variants created by chemical synthesis indicated that the uncommon cis-vaccenic acid was required solely at the sn-2 position, a variant we called SPN Glc-DAG-s2. Four other variants tested, including a glycolipid lacking cis-vaccenic acid, one with cis-vaccenic acid at the sn-1 position, or one with cis-vaccenic acid at both glycerol positions all failed to activate mouse or human iNKT cells [114].

As noted above, GSL bacterial antigens were shown to be more potent with a galactose or galacturonic acid compared to glucose or glucuronic acid, the difference between the two types of sugars being the orientation of the hydroxyl in the 4' position of the hexose sugar. A recent structural analysis illustrates why the glucose sugar is preferred with DAG antigens containing cis-vaccenic acid, providing a vivid illustration of the interplay between the sugar and the CD1d-buried lipid in forming an epitope for the semi-invariant TCR. The glucose in Glc-DAG-s2 leads to a loss of a hydrogen bond with Asn at position 30 of CDR1 of the TCR α chain compared to binding the galactose from BbGL-IIc, but once the TCR is bound a new contact is made between the equatorial 4' hydroxyl of the glucose with Gly155 on the α2 helix of mouse CD1d. This change does not lead to a large difference in the affinity of the semi-invariant TCR for glycolipid mouse CD1d complexes, which is 4.4 μM for SPN Glc-DAG-s2 and 6.2 μM for BbGL-IIc [110, 115]. However, the glucose is important in the context of the Glc-DAG-s2 lipid, because the axial hydroxyl at the 4' position of galactose, meaning the hydroxyl is facing up from rather than parallel to the hexose ring, would not permit the contact with position 155 of mouse CD1d to form. In fact, when galactose is combined in a synthetic antigen in α linkage with the S. pneumoniae DAG containing vaccenic acid, it does not stimulate iNKT cells [114].

Interestingly, although the equilibrium binding constants are similar, when binding the S. pneumoniae antigen, the TCR has both a slower association rate and a slower dissociation rate compared to binding to the Borrelia antigen. This fits our model that the TCR first contacts the exposed sugar, with the ability to contact the sugar affecting primarily the association rate. Subsequent contacts with and accommodation of CD1d affect primarily the dissociation rate, with the glucose interaction with position 155 proposed to be responsible for the more stable binding to complexes of Glc-DAG-s2 by the semi-invariant TCR compared to BbGL-IIc, once the trimolecular complex has formed. Also consistent with this hypothesis are the changes observed over the F' roof of the CD1d groove. Figure 2 shows that in the absence of TCR engagement only αGalCer binding causes a closing of the roof over the F' pocket. Even for the GalA-GSL antigen, this F' roof is open, exposing part of the lipid tail in the groove. Although the association rates of the iNKT cell TCR for the two GSL antigens are similar, the TCR dissociation rate for GalA-GSL-CD1d complexes is faster. We attribute this faster rate to the opening of the F' pocket and a possible flexing of the CD1d molecule even after the TCR is bound. Therefore, the ability of αGalCer to lock CD1d into the optimal conformation accounts in part for its extraordinary ability of αGalCer-CD1d complexes bind to the semi-invariant TCR.

Summary, conclusion, and perspectives

From the discovery of the first antigen in a marine sponge, which in fact was most likely associated with a Sphingomonas-like microorganism that produced the GSL antigen that was originally isolated, much has been learned in recent years about the diverse microbial sources of the glycolipid antigens that activate iNKT cells. Although such antigens may not be found in all bacteria, they can be derived from either Gram-negative or Gram-positive organisms, and from pathogens, commensals, or environmental bacteria. They have an α-linked hexose sugar and primarily contain one of two types of lipids: GSLs or DAGs. Recently, however, a cholesterol-containing glycolipid that activates iNKT cells has been obtained from Helicobacter pylori, the organism that causes stomach ulcers [116]. Therefore, it is likely that the diversity of antigens recognized by the semi-invariant TCR has not been exhausted.

Much has learned as well about the biochemical basis for the specificity of the semi-invariant TCR, including the factors determining the high affinity reactivity for complexes of αGalCer bound to CD1d, how the binding of GSLs and DAG antigens to CD1d differs, and how the kinetic parameters of TCR binding are determined by the position of the sugar for the association rate, and the flexibility of CD1d for the dissociation rate. While ultimately most of the critical features of antigen recognition by the semi-invariant TCR relate to the specific binding to the monosaccharides displayed on the surface of the CD1d antigen presenting protein, critically important as well is the role that the CD1d-bound lipid plays in positioning this sugar.

Years ago Janeway proposed that pattern recognition receptors would allow cells of the innate immune system to recognize critical or conserved molecular features of microbes that are not present in the host [117]. Considering how abundant the microbial glycolipid antigens are, the likelihood they are critical for microbe survival, and the absence of α-linked GSL or DAG antigens in mammalian hosts, when bound to CD1d these glycolipids constitute a kind of microbial associated molecular pattern that stimulates a subpopulation of T cells that carry out innate-like responses. The analogy to pattern recognition receptors may not be perfect, as self-GSL compounds are able to activate iNKT cells to some degree, although this requires a TCR-induced accommodation of the β-linked sugar to a position similar to the α-linked saccharides. However, this does not invalidate the comparison, as toll like receptors, the paradigm of innate cell pattern recognition receptors, are also known to bind to self as well as microbial components. It should be noted that iNKT cells also can be activated by cytokines, particularly IL-12 [44], or by self-antigens presented by CD1d plus IL-12. In a recent study, the authors found that the responses to bacteria that are known to have antigens, such S. pneumoniae, and those not known to have antigens, such as E. coli, are similar in intensity, their requirement for CD1d expression, and their requirement for IL-12 [118]. From these data, the authors concluded that even for microbes expressing a foreign antigen, the responses to self-antigens are predominant. However, this conclusion remains speculative, in part because removal of either the self antigen(s) or the bacterial antigens is not yet possible for technical reasons, making it difficult to weight their relative importance for iNKT cell stimulation. In our view, it seems unlikely that a glycolipid antigen comprising more than 40% of the total glycolipid, as is the case for S. pneumoniae, does not contribute to iNKT cell activation, although this does not exclude a role for self-antigen.

In addition to further exploration of microbial antigens, future work likely will explore in depth the structural basis for the recognition of different glycolipids by human iNKT cells. Furthermore, as αGalCer was first developed as an anti-cancer agent, research undoubtedly will focus on the design of antigens that might be even more effective in clinical settings, such as in the treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants AI45053, AI71922, AI69296, and AI74952.

References

- 1.Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Van Kaer L. iNKT-cell responses to glycolipids. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:183–213. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuda JL, et al. CD1d-restricted iNKT cells, the `Swiss-Army knife' of the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:358–368. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen NR, Garg S, Brenner MB. Antigen Presentation by CD1 Lipids, T Cells, and NKT Cells in Microbial Immunity. Adv Immunol. 2009;102:1–94. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godfrey DI, et al. NKT cells: what's in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silk JD, et al. Structural and functional aspects of lipid binding by CD1 molecules. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:369–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tupin E, Kinjo Y, Kronenberg M. The unique role of natural killer T cells in the response to microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:405–417. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behar SM, Porcelli SA. CD1-restricted T cells in host defense to infectious diseases. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:215–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott-Browne JP, et al. Germline-encoded recognition of diverse glycolipids by natural killer T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1105–1113. doi: 10.1038/ni1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Germain RN, Margulies DH. The biochemistry and cell biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cresswell P. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heemels MT, Ploegh H. Generation, translocation, and presentation of MHC class I-restricted peptides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMichael AJ, et al. A human thymocyte antigen defined by a hybrid myeloma monoclonal antibody. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:205–210. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard A, Boumsell L. The clusters of differentiation (CD) defined by the First International Workshop on Human Leucocyte Differentiation Antigens. Hum Immunol. 1984;11:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(84)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasmar A, Van Rhijn I, Moody DB. The evolved functions of CD1 during infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabi F, Milstein C. The molecular biology of CD1. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:503–509. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delia D, et al. CD1c but neither CD1a nor CD1b molecules are expressed on normal, activated, and malignant human B cells: identification of a new B-cell subset. Blood. 1988;72:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith ME, Thomas JA, Bodmer WF. CD1c antigens are present in normal and neoplastic B-cells. J Pathol. 1988;156:169–177. doi: 10.1002/path.1711560212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Res P, et al. Downregulation of CD1 marks acquisition of functional maturation of human thymocytes and defines a control point in late stages of human T cell development. J Exp Med. 1997;185:141–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Exley M, et al. CD1d structure and regulation on human thymocytes, peripheral blood T cells, B cells and monocytes. Immunology. 2000;100:37–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pena-Cruz V, et al. Epidermal Langerhans cells efficiently mediate CD1a-dependent presentation of microbial lipid antigens to T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:517–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougan SK, Kaser A, Blumberg RS. CD1 expression on antigen-presenting cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:113–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowles RW, Bodmer WF. A monoclonal antibody recognizing a human thymus leukemia-like antigen associated with beta 2-microglobulin. Eur J Immunol. 1982;12:676–681. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830120810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin LH, et al. Structure and expression of the human thymocyte antigens CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:9189–9193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longley J, et al. Molecular cloning of CD1a (T6), a human epidermal dendritic cell marker related to class I MHC molecules. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92:628–631. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12712175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilsland CA, Milstein C. The identification of the beta 2-microglobulin binding antigen encoded by the human CD1D gene. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:71–78. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Salle H, et al. Assistance of microbial glycolipid antigen processing by CD1e. Science. 2005;310:1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.1115301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prigozy TI, et al. Glycolipid antigen processing for presentation by CD1d molecules. Science. 2001;291:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang SJ, Cresswell P. Saposins facilitate CD1d-restricted presentation of an exogenous lipid antigen to T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:175–181. doi: 10.1038/ni1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winau F, et al. Saposin C is required for lipid presentation by human CD1b. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/ni1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou D, et al. Editing of CD1d-bound lipid antigens by endosomal lipid transfer proteins. Science. 2004;303:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1092009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan W, et al. Saposin B is the dominant saposin that facilitates lipid binding to human CD1d molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5551–5556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700617104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiu YH, et al. Multiple defects in antigen presentation and T cell development by mice expressing cytoplasmic tail-truncated CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:55–60. doi: 10.1038/ni740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jong A, et al. CD1a-autoreactive T cells are a normal component of the human alphabeta T cell repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ni.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spada FM, et al. Self-recognition of CD1 by gamma/delta T cells: implications for innate immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;191:937–948. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendelac A. CD1: presenting unusual antigens to unusual T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;269:185–186. doi: 10.1126/science.7542402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benlagha K, et al. In vivo identification of glycolipid antigen-specific T cells using fluorescent CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1895–1903. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuda JL, et al. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;192:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawano T, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brigl M, et al. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagarajan NA, Kronenberg M. Invariant NKT cells amplify the innate immune response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2007;178:2706–2713. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sada-Ovalle I, et al. Innate invariant NKT cells recognize Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, produce interferon-gamma, and kill intracellular bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000239. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyznik AJ, et al. Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J Immunol. 2008;181:4452–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitamura H, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1121–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vincent MS, et al. CD1-dependent dendritic cell instruction. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/ni851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galli G, et al. CD1d-restricted help to B cells by human invariant natural killer T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1051–1057. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leadbetter EA, et al. NK T cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8339–8344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801375105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu TY, et al. Distinct subsets of human invariant NKT cells differentially regulate T helper responses via dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1012–1023. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui J, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278:1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong S, et al. The natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide prevents autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:1052–1056. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Vliet HJ, et al. The immunoregulatory role of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells in disease. Clin Immunol. 2004;112:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crowe NY, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lappas CM, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation reduces hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting CD1d-dependent NKT cell activation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2639–2648. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.VanderLaan PA, et al. Characterization of the natural killer T-cell response in an adoptive transfer model of atherosclerosis. The American journal of pathology. 2007;170:1100–1107. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pichavant M, et al. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Getz GS, Vanderlaan PA, Reardon CA. Natural killer T cells in lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:814–819. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kenna T, et al. NKT cells from normal and tumor-bearing human livers are phenotypically and functionally distinct from murine NKT cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1775–1779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molling JW, et al. Peripheral blood IFN-gamma-secreting Valpha24+Vbeta11+ NKT cell numbers are decreased in cancer patients independent of tumor type or tumor load. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:87–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Natori T, et al. Agelasphins, novel antitumor and immunostimulatory cerebrosides from the marine sponge Agelas mauritianus. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:2771–2784. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sidobre S, et al. The V alpha 14 NKT cell TCR exhibits high-affinity binding to a glycolipid/CD1d complex. J Immunol. 2002;169:1340–1348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cantu C, 3rd, et al. The paradox of immune molecular recognition of alpha-galactosylceramide: low affinity, low specificity for CD1d, high affinity for alpha beta TCRs. J Immunol. 2003;170:4673–4682. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sidobre S, et al. The T cell antigen receptor expressed by Valpha14i NKT cells has a unique mode of glycosphingolipid antigen recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12254–12259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404632101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zajonc DM, et al. Crystal structures of mouse CD1d-iGb3 complex and its cognate Valpha14 T cell receptor suggest a model for dual recognition of foreign and self glycolipids. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel O, et al. NKT TCR Recognition of CD1d-{alpha}-C-Galactosylceramide. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:4705–4713. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wun KS, et al. A molecular basis for the exquisite CD1d-restricted antigen specificity and functional responses of natural killer T cells. Immunity. 2011;34:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ortaldo JR, et al. Dissociation of NKT stimulation, cytokine induction, and NK activation in vivo by the use of distinct TCR-binding ceramides. J Immunol. 2004;172:943–953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xing GW, et al. Synthesis and human NKT cell stimulating properties of 3-O-sulfo-alpha/beta-galactosylceramides. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2005;13:2907–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu D, et al. Bacterial glycolipids and analogs as antigens for CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1351–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408696102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raju R, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 3"- and 4"-deoxy and -fluoro analogs of the immunostimulatory glycolipid, KRN7000. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4122–4125. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou D, et al. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morita M, et al. Structure-activity relationship of alpha-galactosylceramides against B16-bearing mice. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2176–2187. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brossay L, et al. Structural requirements for galactosylceramide recognition by CD1-restricted NK T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5124–5128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sakai T, et al. Syntheses of biotinylated alpha-galactosylceramides and their effects on the immune system and CD1 molecules. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1836–1841. doi: 10.1021/jm990054n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413:531–534. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ndonye RM, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of sphinganine analogues of KRN7000 and OCH. J Org Chem. 2005;70:10260–10270. doi: 10.1021/jo051147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pellicci DG, et al. Recognition of beta-linked self glycolipids mediated by natural killer T cell antigen receptors. Nature immunology. 2011;12:827–833. doi: 10.1038/ni.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yu ED, et al. Cutting Edge: Structural basis for the recognition of beta-linked glycolipid antigens by invariant NKT cells. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:2079–2083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O'Konek JJ, et al. Mouse and human iNKT cell agonist beta-mannosylceramide reveals a distinct mechanism of tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:683–694. doi: 10.1172/JCI42314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brennan PJ, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells recognize lipid self antigen induced by microbial danger signals. Nature immunology. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ni.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Selmi C, et al. Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis react against a ubiquitous xenobiotic-metabolizing bacterium. Hepatology. 2003;38:1250–1257. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wei B, et al. Commensal microbiota and CD8+ T cells shape the formation of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1218–1226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hajiroussou V, et al. Meningitis caused by Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:953–955. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.9.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Southern PM, Jr., Kutscher AE. Pseudomonas paucimobilis bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13:1070–1073. doi: 10.1128/jcm.13.6.1070-1073.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Glupczynski Y, et al. Pseudomonas paucimobilis peritonitis in patients treated by peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1225–1226. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1225-1226.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mattner J, et al. Liver autoimmunity triggered by microbial activation of natural killer T cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meyer EH, et al. Glycolipid activation of invariant T cell receptor+ NK T cells is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity independent of conventional CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2782–2787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kawahara K, et al. Structural analysis of two glycosphingolipids from the lipopolysaccharide-lacking bacterium Sphingomonas capsulata. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1837–1846. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawahara K, et al. Structural analysis of a new glycosphingolipid from the lipopolysaccharide-lacking bacterium Sphingomonas adhaesiva. Carbohydr Res. 2001;333:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kawahara K, et al. Confirmation of the anomeric structure of galacturonic acid in the galacturonosyl-ceramide of Sphingomonas yanoikuyae. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kinjo Y, et al. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 2005;434:520–525. doi: 10.1038/nature03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mattner J, et al. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sriram V, et al. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1692–1701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Long X, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of stimulatory properties of Sphingomonadaceae glycolipids. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:559–564. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kinjo Y, et al. Natural Sphingomonas glycolipids vary greatly in their ability to activate natural killer T cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kawahara K, et al. Chemical structure of glycosphingolipids isolated from Sphingomonas paucimobilis. FEBS Lett. 1991;292:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80845-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kawahara K, et al. Occurrence of an alpha-galacturonosyl-ceramide in the dioxin-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas wittichii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;214:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zeng Z, et al. Crystal structure of mouse CD1: An MHC-like fold with a large hydrophobic binding groove. Science. 1997;277:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu D, et al. Design of natural killer T cell activators: structure and function of a microbial glycosphingolipid bound to mouse CD1d. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3972–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600285103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kumar H, et al. Cutting edge: CD1d deficiency impairs murine host defense against the spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 2000;165:4797–4801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roark JH, et al. CD1.1 expression by mouse antigen-presenting cells and marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:3121–3127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Belperron AA, Dailey CM, Bockenstedt LK. Infection-induced marginal zone B cell production of Borrelia hermsii-specific antibody is impaired in the absence of CD1d. J Immunol. 2005;174:5681–5686. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tupin E, et al. NKT cells prevent chronic joint inflammation after infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19863–19868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810519105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee WY, et al. An intravascular immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi involves Kupffer cells and iNKT cells. Nature immunology. 2010;11:295–302. doi: 10.1038/ni.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Olson CM, Jr., et al. Local production of IFN-gamma by invariant NKT cells modulates acute Lyme carditis. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:3728–3734. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ben-Menachem G, et al. A newly discovered cholesteryl galactoside from Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7913–7918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232451100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kinjo Y, et al. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:978–986. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang J, et al. Lipid binding orientation within CD1d affects recognition of Borrelia burgorferi antigens by NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1535–1540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909479107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O'Brien KL, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kawakami K, et al. Critical role of Valpha14+ natural killer T cells in the innate phase of host protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. European journal of immunology. 2003;33:3322–3330. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nakamatsu M, et al. Role of interferon-gamma in Valpha14+ natural killer T cell-mediated host defense against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in murine lungs. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kinjo Y, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells recognize glycolipids from pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria. Nature immunology. 2011;12:966–974. doi: 10.1038/ni.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Girardi E, et al. Unique Interplay between Sugar and Lipid in Determining the Antigenic Potency of Bacterial Antigens for NKT Cells. PLoS biology. 2011;9:e1001189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chang YJ, et al. Influenza infection in suckling mice expands an NKT cell subset that protects against airway hyperreactivity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:57–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI44845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA., Jr. Innate immunity: the virtues of a nonclonal system of recognition. Cell. 1997;91:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brigl M, et al. Innate and cytokine-driven signals, rather than microbial antigens, dominate in natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:1163–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]