Abstract

Objective

It has been proposed that proprioceptive impairments observed in knee osteoarthritis (OA) may be associated with disease-related changes in joint mechanics. The aim of this study was to quantify joint proprioception and stiffness in the frontal plane of the knee in persons with and without knee OA and to report the associations between these two metrics.

Methods

Thirteen persons with knee OA and fourteen healthy age-matched subjects participated. Proprioceptive acuity was assessed in varus and valgus using the threshold to detection of movement (TDPM). Passive joint stiffness was estimated as the slope of the normalized torque-angle relationship at 0° joint rotation (neutral) and several rotations in varus and valgus. Analyses of variance were performed to determine the effect of OA and gender on each metric. Linear regression was used to assess the correlation between TDPM and joint stiffness.

Results

TDPM was significantly higher (P<0.05) in the OA group compared to controls for both varus and valgus, but significant gender differences were observed. Passive joint stiffness was significantly reduced (P<0.05) in OA participants compared to the control group in neutral and valgus, but not varus, and significantly reduced in females compared to males. A weak negative correlation was observed between TDPM and stiffness estimates, suggesting that poorer proprioception was associated with less joint stiffness.

Conclusions

While both joint stiffness and proprioception were reduced in the OA population, they were only weakly correlated. This suggests that other neurophysiological factors play a larger role in the proprioceptive deficits in knee OA.

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a debilitating musculoskeletal condition which involves the progressive loss of articular cartilage, development of osteophytes, joint malalignment, and muscle atrophy. The pathological alterations in the joint are associated with a number of biomechanical and neurological impairments, such as muscle weakness, joint laxity, proprioceptive deficits, and pain, which contribute to disease-associated functional limitations, and ultimately, disability (1). In a vicious cycle, these physical impairments may lead to further progression of the disease. For example, cartilage loss and subsequent joint space narrowing result in ligament insertion sites moving closer together, often causing increased joint laxity, particularly in the frontal plane of the knee (2). This may lead to abnormal movement of the tibia with respect to the femur, causing detrimental stresses on the articular cartilage (2). The decrease in passive joint stability potentially places a greater burden on the musculoskeletal system to maintain joint stability and prevent harmful loading. In this context, enhancing joint proprioception may aid in developing a motor control strategy to compensate for changes in joint mechanics. However, as proprioception relies on sensory feedback from specialized mechanoreceptors located in muscle, tendon, ligament, and skin (3), it has been suggested that proprioceptive deficits in knee OA may be associated with the disease-related changes in joint laxity (4). The exact nature of this association is not well understood.

To our knowledge, only two studies have reported correlations between joint laxity and proprioception in a knee OA population, though in each case, this association was not the primary outcome of the study. Both Pai et al. (5) and van der Esch et al. (6) reported no significant correlation between varus-valgus joint laxity and proprioception in knee flexion-extension. A potential limitation of these analyses, however, was that each metric was assessed in a different plane of movement and presumably targeted different joint structures (knee flexion-extension primarily engages the muscles, while frontal plane rotation targets the collateral ligaments and capsule). As such, a lack of correlation is perhaps not surprising and the contribution of joint laxity to proprioceptive acuity in knee OA remains largely unknown.

While knee joint proprioceptive acuity has typically been measured in the sagittal plane (knee flexion/extension), we have recently reported on proprioceptive capabilities in the frontal plane of the knee (7–8). The experimental apparatus allows for characterization of both proprioceptive acuity and passive joint stiffness in the same plane of movement. Unlike the aforementioned studies (5–6), this allows for a more direct assessment of the association between proprioception and the intrinsic mechanics of the joint. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was threefold: first, to assess frontal plane proprioceptive acuity in patients with moderate knee OA and healthy age-matched control participants; secondly, to quantify frontal plane passive joint stiffness in each group; and, thirdly, to delineate the associations between frontal plane proprioceptive acuity and joint stiffness. Similar to previous reports, we hypothesize that both proprioceptive acuity (4–6, 9–11) and passive stiffness (2, 12) will be reduced in knee OA participants compared with the control group. Further, we hypothesize that decreased proprioceptive acuity will be associated with reduced joint stiffness in the knee OA population. While it has been proposed that these two disease-related impairments may be associated (4), this will be the first study to provide quantitative assessments of these metrics in the same plane of movement. In this context, our goal is to examine the relative contribution of passive joint stiffness to the proprioceptive abilities in the OA population. Exploring these potential interactions will help elucidate the neuro-mechanical contributions to knee OA and may provide a basis for the continued improvement of therapies and treatments in OA.

Methods

Subjects

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University and complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Thirteen persons with knee OA (7 males, 6 females) and fourteen age- and gender-matched healthy control subjects (7 males, 7 females) participated in the study after providing informed consent. Participants in the knee OA group had been diagnosed with unilateral or bilateral tibio-femoral knee OA according to American College of Rheumatology guidelines and presented radiographic evidence of OA in the symptomatic knee(s) with a Kellgren/Lawrence grade of 2 or 3. Participants in the control group were age and gender-matched to the knee OA participants and were included if they exhibited no pain or symptoms of tibio-femoral knee OA. Exclusion criteria for both groups included the presence of current hip or spine disease, other forms of arthritis (i.e, rheumatoid), previous invasive procedure at the knee within the last 12 months, or history of neurological disorders. Prior to testing, all participants were evaluated by a physical therapist to screen for potential limitations in range of motion and to assess joint alignment and balance.

All study participants completed the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), to characterize subjective knee function and symptoms (13). The WOMAC index consists of three subscales which assess disease-related pain, stiffness, and physical function during daily living activities. Each of the 24 questions is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, in which higher scores are associated with poorer outcomes (greater limitations/more pain). Scores for each subscale are obtained as the sum of the responses. WOMAC scores and a summary of subject demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject demographics. Reported as mean (SD)

| OA Subjects | Control Subjects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 13) | Males (N = 7) | Females (N = 6) | All (N = 14) | Males (N = 7) | Females (N = 7) | |

| Age (years) | 57 (10) | 54 (7) | 60 (12) | 56 (15) | 53 (7) | 65 (4) |

| Height (m) | 1.70 (0.11) | 1.79 (0.03) | 1.60 (0.04) | 1.70 (0.08) | 1.75 (0.06) | 1.64 (0.05) |

| Weight (kg) | 84 (19)* | 89 (20) | 78 (17) | 72 (14) | 80 (13) | 63 (10) |

| BMI (kg/m^2) | 29 (7)* | 28 (7) | 31 (7) | 25 (4) | 26(4) | 24 (4) |

| Q Angle (deg) | 17.4 (5.6) | 15.1 (5.6) | 20.0 (4.6) | 16.1 (6.3) | 12.3 (5.4) | 20.0 (4.8) |

| WOMAC Scores (range) | ||||||

| Pain (0 – 20) | 7.2 (3.1) | 6.8 (2.5) | 7.6 (3.7) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Stiffness (0 – 8) | 3.3 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.6 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| Phys. Functioning | ||||||

| (0 – 68) | 24.3 (11.8) | 26.7 (12.4) | 22.3 (11.9) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Total (0 – 96) | 34.8 (15.6) | 36.5 (16.7) | 33.4 (15.8) | 1.0 (2.4) | 1.7 (3.3) | 0.3 (0.8) |

OA subjects significantly increased compared to control subjects (P<0.05 by two sample t-test)

Experimental procedures

The more affected limb of knee OA subjects and the right leg of control subjects were tested. Within the knee OA population, the more affected limb was identified using Kellgren/Lawrence scores as well as participants’ subjective rating of pain and function in each knee. The experimental apparatus used for testing has been described previously (8, 14). It includes a servomotor actuator equipped with a precision potentiometer and tachometer, as well as a six degrees-of-freedom load cell (JR3, Inc. Woodland, CA, USA) to record the position, force, and torque signals during each experiment.

Subjects were seated in an experimental chair with the knee at neutral flexion/extension (0° knee flexion, as measured by a universal goniometer). The subject’s ankle was placed in a modified aircast (Aircast, DJO Inc. Vista, CA, USA) and then secured to the servomotor actuator, via a rigid cantilever beam. The beam was visually aligned with the subject’s lower leg and the subject was allowed to assume his/her natural frontal plane knee joint alignment. Brackets were securely fastened around the knee joint just proximal to the femoral epicondyles to prevent medial/lateral translation of the femur during testing. In addition, a strap was placed over the thigh to prevent movement of the proximal limb.

Subjects were instructed to remain relaxed during the data collection phases of the experimental session. Surface EMG electrodes (Delsys Bagnoli 3.1, Boston, MA, USA) recorded muscle activity in the semitendinosus, biceps femoris, adductor magnus, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, and vastus lateralis throughout the loading protocol to ensure that subjects maintained a relaxed state. Baseline EMG was collected 100 ms prior to the onset of the angular excursion. Unacceptable EMG activity was identified when the mean EMG activity was greater than two standard deviations above the mean baseline activity for a period of at least 50 ms. Trials that showed unacceptable EMG activity during the data acquisition period were rejected (8). None of the trials collected to be analyzed were excluded based on EMG.

Frontal plane stiffness protocol

Frontal plane passive joint stiffness was assessed following a procedure similar to that described by Cammarata and Dhaher (15). The loading protocol consisted of applying a quasi-static frontal plane stretch to the knee joint at a constant velocity (3°/s). Starting from the neutral position the servomotor rotated the subjects’ knee to 7° of valgus, then to 7° of varus, and then back to the neutral position. To ensure that subjects were comfortable with the applied joint rotations in the frontal plane, several smaller stretches were applied at the beginning of the experimental session. Starting at 3°, the stretches were incrementally increased by 1° to a maximum 7° rotation and subjects were asked to report any discomfort during these initial stretches. Two study participants (one knee OA, one control) reported discomfort with an initial 7° rotation; therefore, the loading protocol was performed to a maximum of 6° in these subjects. All remaining study participants reported no discomfort during the 7° amplitude varus/valgus movement. Following these initial stretches, at least three trials at the targeted amplitude (6° or 7°) were performed.

Proprioceptive testing protocol

Frontal plane proprioception was assessed as the threshold to detection of passive movement (TDPM), following a previously described protocol (8). Briefly, the knee was rotated at a velocity of 1°/s and subjects were instructed to press a handheld button as soon as movement of the limb was detected. If a participant failed to detect a joint movement prior to the maximum joint excursion, the TDPM was assigned the maximum value, 5°, of joint rotation. During proprioceptive testing, subjects wore a blindfold and headphones playing white noise to minimize visual and auditory cues associated with the servomotor system. The handheld button relayed a digital binary signal to the data acquisition board, which had a value of 1 when the button was pressed. Following familiarization with the protocol, at least five trials were performed in each testing direction in a randomized order. Each experimental session, including set up, was approximately 1.5 to 2 hours in duration.

Data analysis

To eliminate high-frequency noise associated with the servomotor system, the EMG and load cell signals were online filtered using an eighth order, zero-phase Butterworth filter at a 220 Hz cut-off frequency and then sampled at 1 kHz. Prior to data analysis, position and frontal plane torque signals were filtered using a low-pass first order Butterworth filter with a 4 Hz cutoff frequency.

Frontal plane stiffness

To account for anthropometric differences between subjects, frontal plane torque was normalized by the product of mass (kg) and height (m) (15). Only the loading phases of the frontal plane torque-angular displacement relationship were considered for analysis. Stiffness was estimated as the slope of the torque-angle relationship at several angular excursions. Specifically, stiffness was calculated at 2, 3, 4, and 5° of varus and valgus excursion. In addition, “neutral” stiffness was calculated around zero degrees of joint rotation to quantify the initial resistance provided by the joint soft tissues and bony congruence. Upon inspection of the resulting hysteresis loop, it was noted that there were discontinuities in the torque-angle relationship at neutral joint excursion. Therefore, the neutral stiffness was estimated from the mean of the hysteresis loop between −1° and 1° of joint excursion. The average stiffness estimates across all trials was used in further analysis.

Proprioceptive acuity

TDPM was defined as the position difference between the onset of movement and the subjects’ detection of movement. The subjects’ detection of movement was determined by finding the rising edge of the handheld button signal (i.e. when the binary signal switched from zero to one) and recording the corresponding frontal plane position. The mean TDPM across trials was used in further analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate differences in passive joint stiffness and TDPM between participants with and without knee OA. However, previous reports have demonstrated that gender can influence both joint stiffness (15–16) and proprioception (17). Therefore, to examine the potential effect of gender on the two primary outcomes of this study, two-factor (gender and study group) analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed for passive joint stiffness and TDPM estimates in varus and valgus. Post-hoc Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons for two factor interactions were performed when significant main effects were found.

To explore the association between frontal plane knee joint proprioceptive acuity and intrinsic joint mechanics, linear regression analyses were performed between TDPM measurements and the neutral and terminal (at 5°) passive stiffness estimates in varus and valgus. Pearson correlation coefficients, r, are presented to indicate the strength of the associations.

Results

Passive frontal plane stiffness

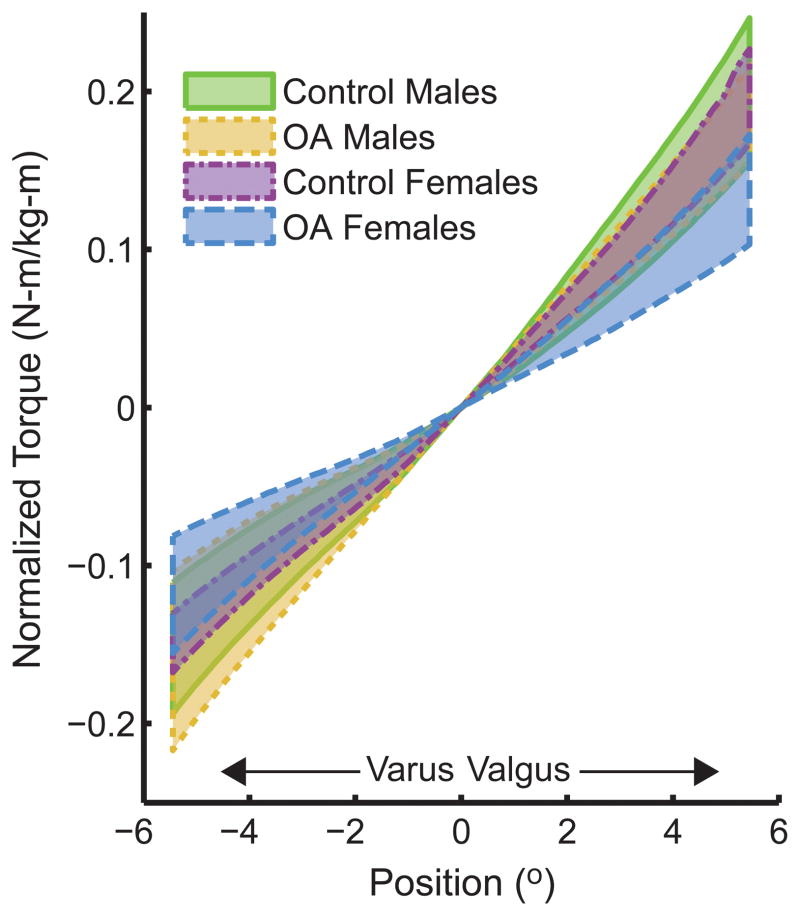

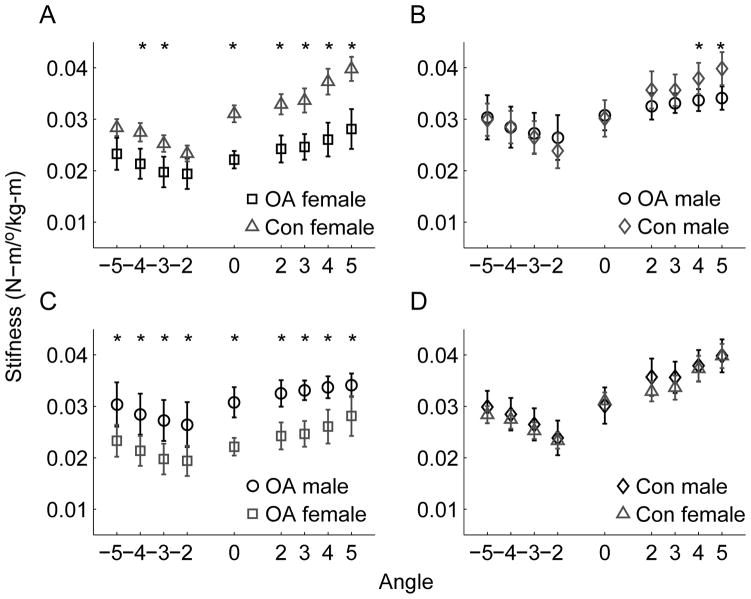

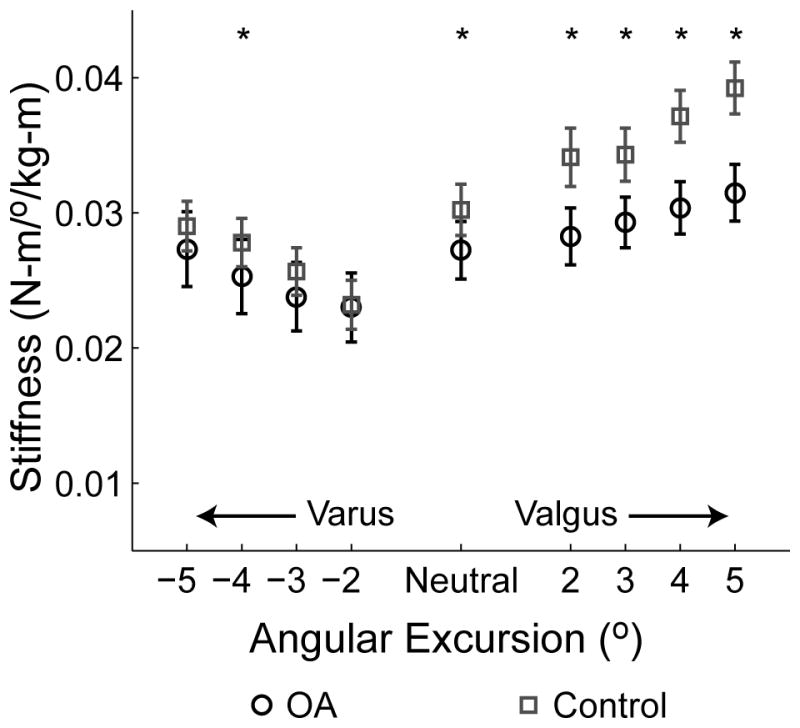

Subjects displayed a non-linear torque-angle relationship in response to mechanical loading in the frontal plane (see Figure 1). Normalized frontal plane stiffness was estimated at neutral varus/valgus, as well as several frontal plane joint angular excursions (2°–5°) in varus and valgus. As shown in Figure 2, stiffness increased with increasing angular rotation in each direction.

Figure 1.

95% confidence intervals of normalized frontal plane torque versus angular displacement for each testing group.

Figure 2.

Normalized frontal plane stiffness as a function of angular excursion. *Stiffness was significantly less (P<0.05) in the OA group compared to the control group. Error bars represent standard error.

Results of the two-factor ANOVA revealed a significant effect of study group (OA vs. control) for neutral stiffness (P = 0.006), and for all valgus stiffness estimates (P<0.0001 at all angular excursions). However, varus stiffness was not significantly different between study groups, except at 4° rotation (P = 0.52, 0.06, 0.03, and 0.12 at 2, 3, 4, and 5°, respectively) (See Figure 2). A significant main effect of gender was found for neutral stiffness (P = 0.001), all valgus stiffness estimates except at 5° rotation (P = 0.0002, <0.0001, 0.003, 0.07, at 2, 3, 4, and 5°, respectively), and all varus stiffness estimates (P = 0.002, 0.0002, 0.002, and 0.001 at 2, 3, 4, and 5°, respectively).

Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons for two-factor interactions revealed that the effect of knee OA appeared to be greater in female than in male participants. Post-hoc analysis showed that stiffness was significantly reduced in OA females compared to control females at neutral, all valgus stiffness estimates, and varus stiffness estimated at 3 and 4° (see Figure 3a). On the other hand, compared to control male participants, only stiffness at 4° and 5° valgus was significantly reduced in OA male subjects (Figure 3b). No significant differences were noted in varus or at neutral between OA and control male subjects. Furthermore, when examining the effect of gender within each study group, it was found that OA females demonstrated reduced stiffness compared to OA males at all angular excursions (Figure 3c). Conversely, no significant differences were noted between control males and females for any stiffness estimates (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Effects of knee OA and gender on normalized frontal plane stiffness as a function of angular excursion across population subgroups. A) effect of OA in the female population. B) effect of OA in the male population. C) effect of gender in the OA group. D) effect of gender in the control group. *Denotes a statistically significant difference (P<0.05). Error bars represent standard error.

Proprioceptive acuity

TDPM in varus and valgus was found to be increased in the knee OA group compared to the control group, indicating reduced proprioceptive acuity (see Table 2). Two-factor ANOVA revealed a significant effect of study group (P = 0.004 for varus and 0.0003 for valgus). However, TDPM was not significantly different between genders (P = 0.64 for varus and 0.47 for valgus). Tukey-Kramer tests for two-factor interactions revealed that TDPM for OA females was significantly greater than for control females.

Table 2.

TDPM results (degrees). Reported as mean (SD)

| OA Subjects | Control Subjects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 13) | Females (N = 6) | Males (N = 7) | All (N = 14) | Females (N = 7) | Males (N = 7) | |

| Valgus | 1.64 (0.84)* | 1.93 (1.04)# | 1.41 (0.82) | 0.71 (0.24) | 0.62 (0.22) | 0.81 (0.23) |

| Varus | 1.68 (1.06)* | 1.97 (1.31)# | 1.44 (0.97) | 0.77 (0.22) | 0.64 (0.17) | 0.90 (0.20) |

Significantly different than control group

Significantly different than control females (by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test)

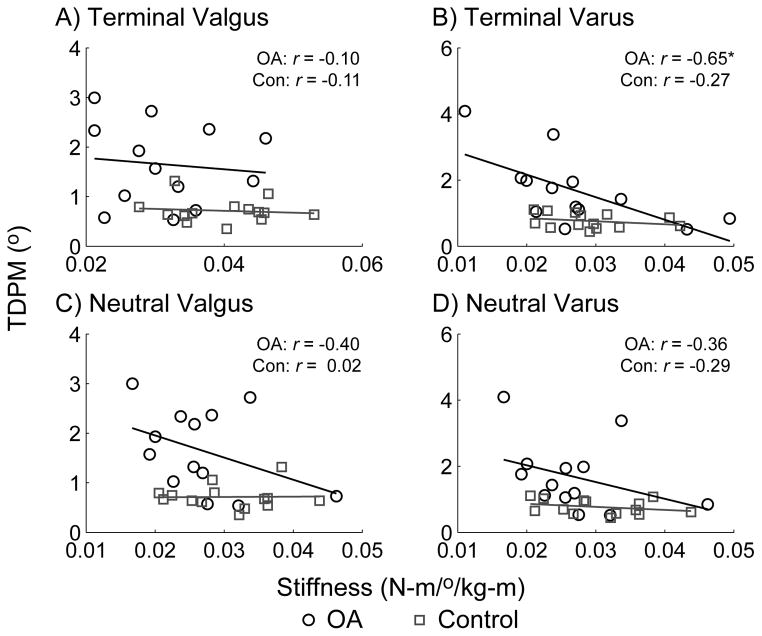

Correlation between stiffness and proprioception

A linear regression analysis was performed between TDPM and the neutral and terminal stiffness estimates (at 5° angular rotation) to assess the correlation between these two metrics. As shown in Figure 4, results indicated a general negative correlation between stiffness estimates and TDPM values, suggesting that less stiffness is associated with poorer proprioception. However, correlation coefficients (and corresponding r2) values were relatively low, indicating a weak statistical association. The only statistically significant correlation coefficient was observed between terminal varus stiffness and varus TDPM in the OA group. Though not presented, similar correlation results were observed between TDPM and the other stiffness estimates. Post-hoc power analysis (G*Power 3.1.2 (18)) indicated that a sample size of 13 provided was sufficient to provide 80% power to detect correlation coefficients of r ≥ 0.06 at the α = 0.05 level.

Figure 4.

Correlation between TDPM (in degrees) and normalized stiffness estimates (in N-m/°/kg-m) in the frontal plane, with associated correlation coefficients, r. A significant correlation (P<0.05) was noted between terminal varus stiffness and TDPM in the knee OA group (plot B). All other associations were insignificant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first examination of proprioceptive acuity and passive joint stiffness within the frontal plane of movement in knee OA. Measuring both metrics in the same plane of movement allows for a more direct assessment of the association between proprioception and intrinsic joint biomechanics. Our results demonstrated that proprioceptive acuity was reduced in the OA group compared to the healthy, age-matched control group, which agrees with previous examinations of proprioception in the sagittal plane of the knee (4–5, 9–10). Similarly, joint stiffness in valgus and neutral were decreased in the OA group compared to the control group, consistent with previous reports of varus/valgus laxity (2, 12). However, while both frontal plane joint stiffness and proprioceptive acuity were affected by knee OA, we observed only a weak negative correlation between these two metrics, signifying that a large percentage of variation in TDPM is not explained by passive joint stiffness. This suggests that other neurophysiological factors are more strongly associated with the decline in proprioceptive acuity in knee OA.

Association between joint stiffness and proprioceptive acuity

Conscious joint proprioception involves the integration of peripheral sensory feedback with higher order cognitive processes. As the peripheral sensory feedback is derived from mechanoreceptors located in muscle, skin, tendon, and ligaments, the mechanical state of the joint tissues plays a role in mediating the strength of the afferent outflow. Based on the anatomical arrangement of the joint we believe that the varus/valgus rotations primarily targeted the medial and lateral ligamentous tissues of the joint and engaged the periarticular mechanoreceptors during proprioceptive testing (8). Thus, the experimental paradigm used in this study provides assessment of both the mechanics and proprioceptive capabilities in this plane of movement. This allows for a more direct evaluation of the effects of joint mechanics on proprioception than previous studies which have quantified sagittal plane proprioception and frontal plane joint mechanics (5–6, 19).

Potentially, a reduction in passive joint stiffness may contribute to poorer proprioceptive acuity (i.e. greater TDPM values), as the mechanical stimulus to sensory afferents would be decreased. This relationship has similarly been proposed to explain reduced proprioceptive acuity following ACL injury (20) and in hypermobility syndrome (21). Analysis of the current results revealed only a weak and statistically insignificant correlation between proprioceptive acuity and passive joint stiffness (Figure 4). This suggests that though the mechanical properties of the joint may have influenced proprioceptive acuity, it was likely not the primary contributor. Other neurophysiological factors, either at the peripheral or central level, may play a larger role in the proprioceptive deficits observed in the knee OA populations (7). These include a loss of density or sensitivity of the joint and muscle mechanoreceptors (22–23), or changes in the central processing of sensory information (24).

Our conclusion that joint mechanics plays only a small role in the detection of joint movement is supported by the lack of any significant correlation between stiffness and proprioception within the control group. This emphasizes that proprioceptive acuity is a complex, individualized sensation. One may argue that the relevant factor to describe proprioceptive deficits in knee OA is not the absolute level of joint stiffness, but rather the change in joint stiffness associated with the disease. Unfortunately, such changes cannot be determined in this cross-sectional study, but require data from longitudinal studies.

The measurement of joint stiffness used in this study was a macroscopic measurement of the joint mechanics. While we believe that we were directly targeting the medial and lateral ligamentous structures of the joint, the overall joint reaction moment measured is also a function of bony congruence (i.e. osteophytes) and other connective tissues (25). The contribution of individual tissues to joint stiffness/laxity cannot be assessed from these macroscopic measurements of the joint and there is currently not a viable method to isolate the contribution of ligamentous tissues in vivo. Therefore, it is possible that there is an association between proprioception and the tension in joint soft tissues, but that these properties were not adequately reflected in the current assessment of joint stiffness.

Furthermore, it is also possible that the relatively small sample size included in the study precluded our detection of a significant association between joint stiffness and proprioceptive acuity. Power analysis indicated that at least 13 participants were necessary to detect a significant (at the P = 0.05 level) association. However, as these initial results suggest that joint stiffness was gender-specific, it is also possible that there is a gender-specific association between stiffness and proprioception and the population subgroups were too small to detect this association. As stated previously, this was the first investigation of the relationship between frontal plane joint stiffness and proprioception and therefore, these initial, preliminary results require further investigation with a larger study population.

Modulation of passive joint stiffness with knee OA

Our results indicated that passive joint stiffness was decreased in the OA group compared to the control group, particularly for neutral and valgus stiffness. Most prior studies of frontal plane joint stability in knee OA quantify joint laxity, documenting both increases (2, 12) and decreases (26) in laxity with the disease. To our knowledge, only one study has reported frontal plane joint stiffness in addition to joint laxity in the knee OA population (25). Consistent with our results, it was found that mid-range stiffness, which correlates to neutral stiffness in the present study, was decreased in the OA population (25). Yet, unlike the current study results, Creaby et al (25) found no significant differences in end-range stiffness estimates between knee OA and control populations. This disparity in results may be due to variations in experimental procedures and analysis across studies. Creaby et al (25) performed testing with the knee at 20° flexion, which engages the joint soft tissues differently than at a neutral flexion/extension angle used in the current study (27). Further, Creaby et al (25) utilized a torque-based joint rotation, estimating end-range stiffness over the last 25% of movement, whereas the current study estimated joint stiffness at set joint rotations. Given the non-linear torque-angle response to joint rotation, the end-range stiffness has no direct correlate to the stiffness estimates in the current study, which precludes direct comparison of results across studies.

Furthermore, the various reports of the effect of knee OA on joint stiffness and laxity (2, 12, 25–26) may speak to the complexity of the OA disease process, which appears to have two competing mechanisms that affect joint stiffness. Associated with the early stages of OA, a decrease in cartilage thickness and subsequent joint space narrowing are thought to contribute to reduced joint stiffness (2, 12). Conversely, the development of osteophytes and soft tissue contracture, particularly at the end stage of the disease, may act to increase stiffness (2, 26). As the OA participants in the current study generally had moderate knee OA (K/L scores of 2–3), it is likely that joint space narrowing was the primary mechanism which affected joint stiffness.

The larger difference in valgus stiffness than varus stiffness may be attributed to the fact that the majority of knee OA participants demonstrated medial compartment knee OA. This would lead to decreased joint space on the medial side and slackness of the medial joint tissues, corresponding to decreased stiffness when the joint was moved into valgus (12). Other investigators have reported a correlation between the amount of joint space narrowing and joint laxity (2). However, such associations could not be examined in the current study because the radiographs used to characterize disease severity were not performed in a standardized position, precluding reliable measurements of joint space narrowing.

Similar to previous reports (15, 28), stiffness estimates in the current study were normalized by the product of height and body mass to account for the effect of body size on passive joint stiffness. One may argue that this normalization procedure may have confounded our analysis of the effects of OA, since OA subjects had a significantly higher body mass than control subjects. One potential solution to this issue may have been to recruit older healthy participants with a similar body mass to OA participants. However, given that advancing age and greater body mass both increase the odds of having knee OA (29–30), it would have been difficult to recruit overweight or obese healthy study participants. Therefore, though not without some limitation, we believe that the normalization procedure used in the current study was necessary to account for anthropometric differences across subjects.

Upon closer inspection, our preliminary results suggest that the differences in joint stiffness between OA and healthy participants may be gender-specific. Specifically, female OA participants demonstrated a greater deviation from control females than the corresponding comparison in males. Furthermore, female OA participants generally had decreased stiffness compared to OA males. However, no differences were noted between the control males and females which is in contrast to our previous finding of gender-specific passive stiffness in young, healthy subjects even after normalization to body size (15). A possible mechanism for these apparent gender effects may be hormonally based. It was noted that three of the female control participants were using hormone replacement therapy (HRT), while none of the female OA participants were. As collagen synthesis and degradation in ligaments is affected by the concentration of sex hormones (31–32), potential variations in hormonal concentrations may have contributed to the differences in passive joint stiffness between OA and control females. Similarly, this may have contributed to the lack of difference between control males and females. However, given the relatively small sample size for each subgroup, this explanation is speculative and future testing is necessary to elucidate the effects of hormonal milieu and HRT on joint mechanics in knee OA.

Clinical and Functional Implications

Both proprioceptive deficits and joint laxity may contribute to the progression of knee OA (33). Biomechanically, each of these variables may impair joint stability and potentially contribute to abnormal loading on the articular cartilage. A decreased contribution of the ligamentous-capsular tissues, as indicated by reduced joint stiffness, may place a greater burden on the musculoskeletal system to maintain stability and prevent damaging loading on the articular cartilage (2). Evidence suggests that people with knee OA use co-contraction of the quadriceps and hamstrings to compensate for varus/valgus laxity. However, this strategy may act to increase the axial load on the joint (34). Therefore, neuromuscular training paradigms have been advocated to improve selective motor control in an attempt to reduce joint loading (35–36).

As suggested in our previous work (15), decreased stiffness may limit the ability of the neuromuscular system to reflexively maintain joint stability. However, at least at a conscious level, there does not appear to be a strong relationship between joint mechanics and proprioceptive capabilities. This is consistent with recent studies which have demonstrated that varus/valgus joint laxity does not predict functional ability (i.e. walking) or the perception of joint stability, as characterized by episodes of “giving way” (37). This evidence suggests that functional performance may be better predicted by cognitive assessment of physical capabilities and joint stability, rather than actual biomechanical stability (37–38). Results from the current study in conjunction with these prior reports may suggest that improvement in proprioceptive ability and neuromuscular control may be best addressed by seeking to improve cognitive processing and descending motor function (39).

Conclusions

By quantifying both metrics in the frontal plane of the knee, this study provides, for the first time, a direct assessment of the relationship between joint mechanics and proprioceptive acuity in knee OA. While negative correlations were observed between stiffness and TDPM, the majority of associations were insignificant and the magnitude of the correlation coefficients was relatively low. This suggests that frontal plane joint stiffness contributes to, but cannot entirely explain, proprioceptive acuity in knee OA. Other neurological factors, such as a reduction in the density of mechanoreceptors, or changes in central sensitivity may be the primary contributors to proprioceptive impairments in knee OA. Results from this study provide new insight into the association between neurological and biomechanical impairments common in knee OA. As proprioceptive training is advocated for improving gait and function in knee OA populations, these initial results may suggest that training programs should focus on cognitive factors (such as increasing attention to joint movement), rather than trying to intervene on the peripheral level.

Significance and Innovation.

Quantifying both proprioceptive acuity and joint stiffness in the frontal plane of the knee provides a more direct assessment of the relationship between joint mechanics and proprioception in knee OA.

Though both frontal plane proprioceptive acuity and stiffness were reduced in the knee OA population, they were only weakly correlated. This suggests that joint mechanics only marginally contribute to proprioceptive impairments in knee OA.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR049837 and T32 HD007418), the Arthritis Foundation, and the Alpha Omicron Pi Foundation.

The authors would like to acknowledge Thomas Schnitzer, MD, PhD, for assistance with knee OA subject recruitment and evaluation, as well as scientific and clinical review of the manuscript; Victoria Brander, MD, for assistance with knee OA subject referral; and Jill Landry, PT, for her help with data collection and analysis. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR049837 and T32 HD007418), the Arthritis Foundation, and the Alpha Omicron Pi Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report

References

- 1.Sharma L. The role of proprioceptive deficits, ligamentous laxity, and malalignment in development and progression of knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2004;70:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma L, Lou C, Felson DT, Dunlop DD, Kirwan-Mellis G, Hayes KW, et al. Laxity in healthy and osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):861–70. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<861::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riemann BL, Lephart SM. The Sensorimotor System, Part I: The Physiologic Basis of Functional Joint Stability. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):71–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koralewicz LM, Engh GA. Comparison of proprioception in arthritic and age-matched normal knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(11):1582–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai YC, Rymer WZ, Chang RW, Sharma L. Effect of age and osteoarthritis on knee proprioception. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(12):2260–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Esch M, Steultjens M, Harlaar J, Knol D, Lems W, Dekker J. Joint proprioception, muscle strength, and functional ability in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):787–93. doi: 10.1002/art.22779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cammarata ML, Schnitzer TJ, Dhaher YY. Does knee osteoarthritis differentially modulate proprioceptive acuity in the frontal and sagittal planes of the knee? Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(9):2681–9. doi: 10.1002/art.30436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammarata ML, Dhaher YY. Proprioceptive acuity in the frontal and sagittal planes of the knee: a preliminary study. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(7):1313–20. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1757-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurkmans EJ, van der Esch M, Ostelo RW, Knol D, Dekker J, Steultjens MP. Reproducibility of the measurement of knee joint proprioception in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1398–403. doi: 10.1002/art.23082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma L. Proprioceptive impairment in knee osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25(2):299–314. vi. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma L, Pai YC. Impaired proprioception and osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1997;9(3):253–8. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199705000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewek MD, Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L. Control of frontal plane knee laxity during gait in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(9):745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhaher YY, Tsoumanis AD, Rymer WZ. Reflex muscle contractions can be elicited by valgus positional perturbations of the human knee. J Biomech. 2003;36(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cammarata ML, Dhaher YY. The differential effects of gender, anthropometry, and prior hormonal state on frontal plane knee joint stiffness. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008;23(7):937–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant JT, Cooke TD. Standardized biomechanical measurement for varus-valgus stiffness and rotation in normal knees. J Orthop Res. 1988;6(6):863–70. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boerboom AL, Huizinga MR, Kaan WA, Stewart RE, Hof AL, Bulstra SK, et al. Validation of a method to measure the proprioception of the knee. Gait Posture. 2008;28(4):610–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Esch M, Steultjens M, Harlaar J, Wolterbeek N, Knol DL, Dekker J. Knee varus-valgus motion during gait--a measure of joint stability in patients with osteoarthritis? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(4):522–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts D, Andersson G, Friden T. Knee joint proprioception in ACL-deficient knees is related to cartilage injury, laxity and age: a retrospective study of 54 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(1):78–83. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001708160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fatoye F, Palmer S, Macmillan F, Rowe P, van der Linden M. Proprioception and muscle torque deficits in children with hypermobility syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(2):152–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz RA, Miller DC, Kerr CS, Micheli L. Mechanoreceptors in human cruciate ligaments. A histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(7):1072–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurley MV, Scott DL, Rees J, Newham DJ. Sensorimotor changes and functional performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(11):641–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.11.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund H, Juul-Kristensen B, Hansen K, Christensen R, Christensen H, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, et al. Movement detection impaired in patients with knee osteoarthritis compared to healthy controls: a cross-sectional case-control study. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2008;8(4):391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creaby MW, Wrigley TV, Lim BW, Bowles KA, Metcalf BR, Hinman RS, et al. Varus-valgus laxity and passive stiffness in medial knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010 doi: 10.1002/acr.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brage ME, Draganich LF, Pottenger LA, Curran JJ. Knee laxity in symptomatic osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(304):184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markolf KL, Mensch JS, Amstutz HC. Stiffness and laxity of the knee--the contributions of the supporting structures. A quantitative in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(5):583–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HS, Wilson NA, Zhang LQ. Gender differences in passive knee biomechanical properties in tibial rotation. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(7):937–44. doi: 10.1002/jor.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bijlsma JW, Knahr K. Strategies for the prevention and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(1):59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Ettinger WH, Mueller WH. Body fat distribution and osteoarthritis. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(4):701–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abubaker AO, Hebda PC, Gunsolley JN. Effects of sex hormones on protein and collagen content of the temporomandibular joint disc of the rat. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(6):721–7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu WD, Panossian V, Hatch JD, Liu SH, Finerman GA. Combined effects of estrogen and progesterone on the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(383):268–81. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200102000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma L, Cahue S, Song J, Hayes K, Pai YC, Dunlop D. Physical functioning over three years in knee osteoarthritis: role of psychosocial, local mechanical, and neuromuscular factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(12):3359–70. doi: 10.1002/art.11420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewek MD, Ramsey DK, Snyder-Mackler L, Rudolph KS. Knee stabilization in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2845–53. doi: 10.1002/art.21237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasaki K, Neptune RR. Individual muscle contributions to the axial knee joint contact force during normal walking. J Biomech. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorstensson CA, Henriksson M, von Porat A, Sjodahl C, Roos EM. The effect of eight weeks of exercise on knee adduction moment in early knee osteoarthritis--a pilot study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(10):1163–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506–16. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maly MR, Costigan PA, Olney SJ. Role of knee kinematics and kinetics on performance and disability in people with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21(10):1051–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM, Huston LJ, Fry-Welch D. Can proprioception really be improved by exercises? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(3):128–36. doi: 10.1007/s001670100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]