Abstract

Chronic interstitial cystitis (IC), mostly affecting middle-aged women, is a very rare manifestation of primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS). Hereby, we report a 42-year-old woman with pSS, presenting with dysuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic pain. She was diagnosed to have chronic IC, based upon the cystoscopic biopsy finding of chronic inflammation in the bladder wall. Systemic corticosteroid and azathioprine treatments together with local intravesical therapies were not effective. Therefore, cyclosporine (CSA) therapy was initiated. Initial low dose of CSA (1.5 mg/kg/d) improved the symptoms of the patient, with no requirement for dose increment. After 4 months of therapy, control cystoscopic biopsy showed that bladder inflammation regressed and IC improved. This case suggests that even low doses of CSA may be beneficial for treating chronic IC associated with pSS syndrome.

Keywords: Primary Sjögren’s syndrome, Interstitial cystitis, Cyclosporine

Introduction

Primer Sjögren syndrome (pSS) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands, and associated with various autoantibodies, especially anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B antibodies [1]. During the progression of pSS, nearly 40% of the pSS patients also develop extraglandular manifestations including pulmonary, hepatic, renal involvement. Other than these extraglandular system/organ involvements, chronic interstitial cystitis (IC) may also occur, albeit rarely, in the course of the pSS, as recently observed in several patients [2–4].

IC, also known as painful bladder syndrome, is a chronic inflammatory disease of the bladder occurring mainly in women (F/M:9/1), primarily during middle ages. IC is largely defined by symptoms of urinary urgency and frequency associated with pelvic pain that varies with bladder filling. Data including the course and the treatment of IC associated with pSS are scarce. Hereby, we report a case of IC complicating pSS, resistant to systemic corticosteroid and azathioprine (AZA) treatments, and local intravesical treatment, but responsive to even low doses of cyclosporine (CSA) treatment.

Case

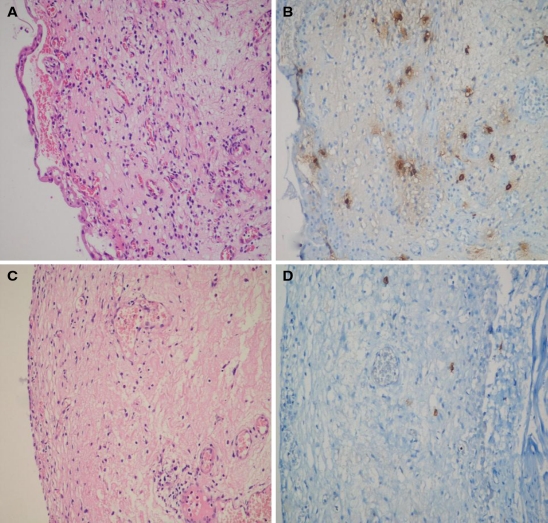

A 42-year-old Turkish woman was admitted to Ege University Rheumatology outpatient clinic on March 2000 with the complaints of dry eyes, dry mouth, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Autoantibody profile showed positive homogenous ANA with a 1/640 titer and positive anti-Ro. Minor salivary gland biopsy revealed Chisholm stage III. These findings led to the diagnosis of pSS based upon the latest European Classification criteria [5] and we commenced hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d. Since 2006, the patient had also suffered from dysuria, urgency, pollakiuria, and suprapubic and perineal pain. Kidney function tests were normal, and urine pH was 5.5. Because of these lower urinary tract symptoms, we performed cystoscopic examination and biopsy in September 2006. The biopsy specimens revealed diffuse epithelial and subepithelial edema with infiltration by lymphocytes and mast cells. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of IC was made. Infectious etiology was excluded by appropriate tests and autoimmune etiology in the context of pSS was considered. Since the case was considered to have extraglandular involvement of pSS, initial treatment consisting of moderate dose methylprednisone (24 mg/day) and AZA (2 mg/kg/day) was commenced on December 2006. The methylprednisone dose was tapered gradually to 4 mg/day in 3 months, and AZA treatment continued in the same dose. However, this treatment remained ineffective and intravesical lidocaine and amitriptyline therapies were also added. Unfortunately, addition of local treatments was helpful only for a short period of time, and after 2 months, symptoms recurred. The Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI) was calculated as 20 points [6]. Therefore, cystoscopic examination and urinary bladder biopsy were repeated on April 2009. The histological findings included ulceration of epithelial cells, urothelial separation and subepithelial hemorrhagia, edematous and hemorrhagic lamina propria and prominent submucosal inflammatory cell infiltration, mostly mast cells. Mast cell tryptase activity implicated substantially increased mast cells (Fig. 1a, b). In addition to clinical inefficacy, these histological findings also supported that AZA therapy was not successful. Therefore, we decided to change the immunosuppressive agent. Since it was previously shown that low dose CSA was a safe and effective choice, we preferred to use CSA (2, 7, 8). The patient was 74 kg in weight and CSA 1.5 mg/kg/day (100 mg/day) was started. Methylprednisolone dose was increased to 24 mg/day, and the dose was gradually decreased to 4 mg/day in 2 months. In the fourth month of therapy, the patient’s lower urinary tract symptoms dramatically improved and the ISCI score decreased to 2 points. Cystoscopy and bladder biopsy were repeated for the third time to assess whether the treatment was also effective from histological point of view. It was found that hemorrhagia and edema in the lamina propria were replaced by early fibrosis and there was only slight inflammatory infiltration mostly consisting of mononuclear cells (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

Histopathologic features on biopsies. The second and third biopsies showing the histologic findings before and after CSA treatment. a–b Histologic findings in the second biopsy, representing the pathology before CSA treatment. Urothelial separation, subepithelial hemorrhagia, edematous lamina propria, and infiltration of inflammatory cells are seen (a). Increase in mast cells is remarkable in the inflammatory infiltration as shown by mast cell tryptase (b). c–d Histologic findings in the third biopsy, showing the effects of CSA treatment. Regenerative properties in urothelium and slight edema in lamina propria and early fibrosis findings (c). CD117 immunostaining shows decrease in the number of mast cells (d)

The patient is currently in the first year of CSA treatment plus low dose methylprednisone. Her complaints are completely regressed and she is being followed up in clinical remission.

Discussion

Hereby, we presented a pSS case complicated with chronic IC, resistant to combination of medium dose steroids, AZA and local intravesical treatments, but successfully treated with low dose of CSA combined with medium to low dose steroids. This patient is also notable with having three cystoscopic biopsies with available histopathologic bladder findings, representing a spectrum ranging from the initial active phase, to post-AZA treatment period (Fig. 1a, b), and finally to remission phase induced by CSA treatment (Fig. 1c, d). In other words, the beneficial effects of CSA were shown not only clinically and by ICSI score, but also by histological examination.

During the course of pSS, interstitial cystitis may develop, albeit rarely [2, 3]. In 1993, Van de Merwe et al. [3] studied 10 patients with IC, 2 of whom were diagnosed as having pSS. Haarala et al. [4] reported the frequency of lower urinary tract problems in patients with pSS. They found that the patients with pSS have significantly more urinary complaints than age- and sex-matched controls (61% vs. 34%, respectively).

Treatment experience is extremely limited in IC complicating pSS. Although traditional disease-modifying agents including hydroxychloroquine and AZA are frequently used in the treatment of extraglandular involvement of pSS, data regarding their efficacy in general and especially in suppressing the symptoms of IC are not available. However, CSA in combination with corticosteroids has been found to be more effective, even in cases of dryness associated with pSS [2]. So, it may be worthwhile to consider CSA treatment in patients with pSS with extraglandular organ involvement. Supporting this view, CSA was favorably used in the treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic IC, as reported in more recent studies. Shibata et al. [2] reported a case with pSS, who presented with bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, acute renal failure and IC, and successfully treated with CSA and steroids. CSA was given at a dose 100 mg daily in that case. Similarly, the dose of CSA used by Sairenen et al. [7, 8] for the maintenance treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic IC was 1–1.5 mg/kg once daily. Based on these reports, we also preferred to switch AZA to low dose CSA, rather than switching to high dose CSA or cyclophosphamide (CYP).

During the course of other chronic autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, interstitial cystitis may also rarely occur. CYP and high dose corticosteroid treatment may be useful at regressing bladder involvement in SLE (lupus cystitis), but not every patient responds satisfactorily to this treatment [9–11].

Intravesical treatment of chronic idiopathic IC generally provides only short-term benefits. Therefore, additional systemic therapy is generally required. Recent publications indicate that best oral systemic treatment options for idiopathic IC include pentosan polysulfate sodium, amitriptyline, hydroxyzine, and CSA [8, 12].

Histopathology of chronic IC is characterized by an increase in the number of the mast cells, as in our case. Activated mast cells release various vasoactive, nociceptive, and proinflammatory molecules that may cause immune cell infiltration and sensory nerve sensitization. The mechanism of action of CSA may involve the inhibition of stem cell factor mediated mast cell activation [13].

In conclusion, the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with pSS should raise the possibility of associated IC. If the diagnosis of IC is confirmed and the differential diagnosis points out an autoimmune origin in the context of pSS, low dose CSA may be a good choice for treatment.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Fox RI. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8:438–445. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibata S, Ubara Y, Sawa N, et al. Severe interstitial cystitis associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Intern Med. 2004;43:248–252. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van de Merwe J, Kamerling R, Arendsen E, et al. Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:962–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haarala M, Alanen A, Hietarinta M, Kiilholma P. Lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunc. 2000;11:84–86. doi: 10.1007/s001920050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1996;49(5A Suppl):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sairanen J, Tammela TL, Leppilahti M, et al. cyclosporine and pentosan polysulfate sodium for the treatment of interstitial cystitis: a randomized comparative study. J Urol. 2005;174:2235–2238. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181808.45786.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sairanen J, Forsell T, Ruutu M. Long-term outcome of patients with interstitial cystitis treated with low dose cyclosporine A. J Urol. 2004;171:2138–2141. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125139.91203.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HJ, Park MH. Obstructive uropathy due to interstitial cystitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Nephrol. 1996;45:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakauchi Y, Suehiro T, Tahara K, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus relapse with lupus cystitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13:645–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meulders Q, Michel C, Marteau P, et al. Association of chronic interstitial cystitis, protein-losing enteropathy and paralytic ileus with seronegative systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. Clin Nephrol. 1992;37:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Ophoven A, Hertle L. Long-term results of amitriptyline treatment for interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2005;174:1837–1840. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176741.10094.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperr WR, Agis H, Czerwenka K, et al. Effects of cyclosporin A and FK-506 on stem cell factor-induced histamine secretion and growth of human mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:389–399. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)70163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]