Abstract

In vertebrates, two condensin complexes exist, condensin I and condensin II, which have differing but unresolved roles in organizing mitotic chromosomes. To dissect accurately the role of each complex in mitosis, we have made and studied the first vertebrate conditional knockouts of the genes encoding condensin I subunit CAP-H and condensin II subunit CAP-D3 in chicken DT40 cells. Live-cell imaging reveals highly distinct segregation defects. CAP-D3 (condensin II) knockout results in masses of chromatin-containing anaphase bridges. CAP-H (condensin I)-knockout anaphases have a more subtle defect, with chromatids showing fine chromatin fibres that are associated with failure of cytokinesis and cell death. Super-resolution microscopy reveals that condensin-I-depleted mitotic chromosomes are wider and shorter, with a diffuse chromosome scaffold, whereas condensin-II-depleted chromosomes retain a more defined scaffold, with chromosomes more stretched and seemingly lacking in axial rigidity. We conclude that condensin II is required primarily to provide rigidity by establishing an initial chromosome axis around which condensin I can arrange loops of chromatin.

Key words: Condensin, Chromosome structure

Introduction

One of the most visually dynamic processes in biology is the dramatic reorganisation that occurs as the chromosome territories of interphase nuclei reorganise to form cytologically distinct X-shaped structures known as mitotic chromosomes. In vertebrates, this condensation process compacts the chromatin up to a further 200 fold (Saitoh et al., 1994). A full understanding of the mechanism underlying this process remains to be determined.

A key advance in understanding chromosome condensation came with the discovery of a pentameric complex termed condensin that was required for both the establishment and maintenance of chromosome condensation in Xenopus egg extracts (Hirano et al., 1997; Hirano and Mitchison, 1994). Animals and plants have two condensin complexes that share core structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 2 (SMC2) and SMC4 subunits but differ in their auxiliary non-SMC components called condensin associated proteins (CAP-D2, CAP-G and CAP-H for condensin I; CAP-D3, CAP-G2 and CAP-H2 for condensin II) (Hirano et al., 1997; Ono et al., 2003). Fungi contain only condensin I, which has a specialized role in rDNA segregation in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hirano, 2005). A condensin-like complex with an SMC homodimer and two non-SMC subunits also exists in bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, where it functions in genome organization and segregation (Graumann and Knust, 2009; Volkov et al., 2003).

In vertebrates, condensin I is cytoplasmic during interphase and loads onto the chromosomes at the end of prophase after nuclear envelope breakdown (Gerlich et al., 2006; Hirota et al., 2004; Ono et al., 2004). Condensin II is nuclear during interphase but does not concentrate on chromatin until prophase, where it remains until the end of telophase.

Condensin I and II localize at centromeres and along the axis of metaphase sister chromatid arms, where they alternate in ‘barber-pole’ fashion, as well as having regions of overlap (Ono et al., 2003). This axial localization of condensin subunits CAP-H and SMC2 (Kireeva et al., 2004; Maeshima and Laemmli, 2003) is consistent with the idea that condensin supports a central scaffold network important for the architecture of mitotic chromosomes (Hudson et al., 2009). While various lines of evidence support the existence of the scaffold as a network of non-histone proteins capable of organizing mitotic chromosomes (Adolph et al., 1977; Hudson et al., 2003; Maeshima and Laemmli, 2003; Paulson and Laemmli, 1977), its biological and functional relevance remain unclear. The condensin complex is essential for chromosome segregation and architecture in all eukaryotes (Dej et al., 2004; Hagstrom et al., 2002; Hudson et al., 2003; Oliveira et al., 2005; Ono et al., 2003; Siddiqui et al., 2006; Strunnikov et al., 1995) – however, the precise roles of condensin I and II remain to be determined.

RNAi depletion studies of condensin subunits have produced a range of phenotypes in vertebrate cells. Mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells show minimal cell cycle defects after RNAi knockdown of either CAP-D2 or CAP-D3 subunits (Fazzio and Panning, 2010). In some studies, condensin I RNAi knockdown produces only weak anaphase defects (Csankovszki et al., 2009; Hirota et al., 2004), whereas, in others, obvious defects are observed (Oliveira et al., 2005; Ono et al., 2004; Savvidou et al., 2005; Watrin and Legagneux, 2005). In one study, indistinguishable anaphase defects were observed following knockdown of condensin I or II (Gerlich et al., 2006). While RNAi is highly convenient for probing gene function, inconsistencies can arise due to differential or weak knockdown or, in some cases, off-target effects (Fedorov et al., 2006).

Our study aimed to resolve the relative roles of condensin I and II by creating chicken DT40 conditional knockouts for the condensin-I-specific subunit CAP-H and condensin II subunit CAP-D3. Using the powerful Tet-off system (Gossen and Bujard, 1992), we could induce a rapid and homogenous shutoff of condensin I (CAP-H KO) and condensin II (CAP-D3 KO), and then closely follow cell populations over time. This allowed us to distinguish primary from secondary defects and to monitor the long-term consequences of the loss of each specific condensin subtype.

Our data show that the loss of CAP-H (condensin I) or CAP-D3 (condensin II) induces highly distinct chromosome structure and segregation phenotypes in DT40 cells. Three-dimensional structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM) of the distinctive kinking and twisting phenotype displayed in mitotic chromosomes following CAP-D3 (condensin II) depletion revealed apparent cross-overs of sister chromatids reminiscent of meiotic cross-overs seen using 3D-SIM (Wang et al., 2009). We suggest that chromosome compaction is a two-step process, with condensin II mediating long-range DNA interactions and establishing an initial chromatin axis that subsequently allows condensin I to mediate short-range lateral interactions and formation of compact loops of chromatin.

Results

Generation of CAP-H and CAP-D3 conditional knockouts in chicken DT40 cells

Conventional conditional knockouts (KOs) of the genes encoding CAP-H and CAP-D3 were prepared in DT40 cells, with knockout cells kept alive by cDNAs expressed under Tet-off regulation. Addition of doxycycline causes a shutoff of transcription of the exogenous cDNA, thereby allowing the mutant phenotype to be displayed as the protein is lost through normal turnover.

The gene encoding CAP-H maps to micro-chromosome 22. Knockout of this gene was relatively straightforward. CAP-H gene-targeting using constructs whose homologous 5′ and 3′ arms were cloned by PCR from genomic DT40 DNA produced +/− heterozygotes in Southern analysis following a first round of gene targeting (Fig. 1A). Co-transfection of CAP-H +/− cells with the Tet-repressible CAP-H rescue cDNA construct with a modified Tet-repressor-transactivator (CMVtTA3) was followed by a second round of gene targeting. This modified tTA transactivator yields a reduced level of target gene expression (Baron et al., 1997).

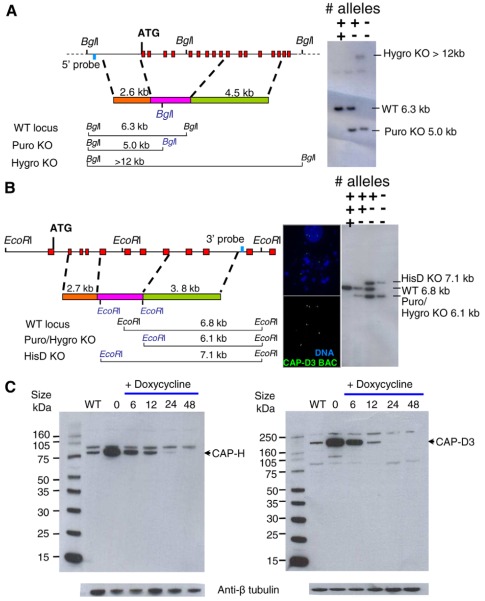

Fig. 1.

Generation of CAP-H and CAP-D3 conditional knockout cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of the CAP-H genomic locus and targeting construct. Exons and external screening probe are shown as red and blue boxes, respectively. Orange and green boxes represent 5′ and 3′ targeting arms flanking the resistance cassette (pink box), with the expected band sizes for wild-type (WT) and genomic BglI digests illustrated in the schematic below. Two targeting constructs with puromycin (puro) and hygromycin (hygro) resistance cassettes were used to target each allele. Southern blot analysis shows sequential gene targeting with puromycin followed by hygromycin constructs. The wild-type 6.3-kb BglI band is replaced by 5.0 and >12 kb fragments for puromycin and hygromycin constructs, respectively. (B) Schematic representation of the CAP-D3 genomic locus; boxes are coloured as in A. FISH analysis with a CAP-D3 BAC clone reveals the presence of three copies of the gene in an interphase cell (top 3 signals) and in a metaphase cell (bottom three signals). Each allele was targeted with a separate targeting construct containing a puromycin, hygromycin or histidinol dehydrogenase (HisD) selectable marker. Southern blot analysis shows the sequential targeting for each allele. The wild-type 6.8-kb EcoRI fragment is replaced by 6.1 kb for the puromycin and hygromycin constructs, and 7.1 kb for the HisD construct. (C) Western blot analysis of SDS-PAGE gels probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CAP-H or CAP-D3. CAP-H- and CAP-D3-specific bands are indicated. Anti-β-tubulin was used as a loading control.

The gene encoding CAP-D3 is present on micro-chromosome 24. Southern analysis following targeting of the first CAP-D3 allele showed a wild-type to targeted allele ratio of 2:1 (+/+/−) (Fig. 1B; supplementary material Fig. S1A), suggesting that chromosome 24 exists as a trisomy in DT40 cells. This was further confirmed by FISH using a CAP-D3 BAC clone that produced three clear signals in interphase cells and three pairs of signals in metaphase cells (Fig. 1B).

A second round of gene targeting yielded CAP-D3 +/−/− cells. These cells express one third the level of CAP-D3 protein as expected for the genotype but exhibit no obvious phenotype (supplementary material Fig. S1B,C). Co-transfection of the Tet-repressible CAP-D3 cDNA rescue construct with a modified Tet-repressor-transactivator (ScIItTA3) into CAP-D3 +/−/− cells was followed by a third round of gene targeting, yielding the expected −/−/− genotype. This version of the transactivator is expressed under control of the SMC2 promoter (Samejima et al., 2008). No CAP-D3 KO cells were generated from CMVtTA3, suggesting that unregulated CAP-D3 expression is deleterious. In general, we will refer to CAP-H or CAP-D3 KO cells when describing doxycycline time-course experiments and CAP-HON/OFF and CAP-D3ON/OFF when referring to single time-points from a given experiment.

Conditional knockout clones were first identified by using a growth assay to reveal clones that died or showed growth defects after doxycycline addition but grew normally without drug. Multiple putative KO clones were isolated for CAP-H and CAP-D3 KOs that died after doxycycline addition. Southern analysis confirmed that all clones were indeed correctly targeted and the final endogenous allele was disrupted as expected (Fig. 1A,B; supplementary material Fig. S1A).

CAP-H and CAP-D3 protein detectable in immunoblots fell to barely detectable levels after 24 hours (approximately two cell cycles) of drug treatment of the respective cell lines (Fig. 1C). We note that, despite the seemingly longer half-life of the CAP-H protein compared with that of CAP-D3, CAP-H is still depleted to 5% of the wild-type level within 24 hours after doxycycline addition (CAP-D3 is not detectable at this point). Likewise, CAP-H and CAP-D3 were no longer detected on chromosomes by indirect immunofluorescence in the respective knockouts after doxycycline treatment (supplementary material Fig. S2). Importantly, we did not detect another condensin I subunit (CAP-D2) on CAP-H-depleted chromosomes. Thus, depletion of one subunit blocks other subunits from the same condensin subcomplex assembling onto chromosomes (supplementary material Fig. S2).

We next examined the cross-dependencies between condensin I and II for localisation on mitotic chromosomes (supplementary material Fig. S2). Both CAP-H- and CAP-D3-depleted chromosomes contained detectable SMC2, suggesting that depletion of one condensin complex did not block the localization of the other complex. This was confirmed by showing that CAP-H and CAP-D2 (condensin I) are present on chromosomes of CAP-D3 (condensin II)-depleted cells. Conversely, CAP-D3 still localized to CAP-H KO chromosomes (supplementary material Fig. S2). Our results confirm previous findings in human cells showing that disruption of any non-SMC subunit would disrupt only its specific condensin subtype (Ono et al., 2003). Importantly, all condensin and scaffold components tested showed similar localisations in CAP-H and CAP-D3 KOs in the absence of doxycycline compared with wild-type DT40 cells, suggesting that the transgenes for the respective KOs led to no detrimental effects.

This analysis reveals that shutting-off the transcription of the genes encoding CAP-H or CAP-D3 results in a rapid depletion of the targeted proteins and loss of their respective complexes from chromosomes. Thus, we will refer to our CAP-H KO as a condensin I complex KO, and CAP-D3 KO as a condensin II KO. Two independent clones of each conditional knockout were selected for subsequent analysis.

Both condensin I (CAP-H) and condensin II (CAP-D3) are essential for cell survival

Our newly constructed CAP-H (condensin I) and CAP-D3 (condensin II) conditional KO cell lines showed growth rates close to those of the wild type, indicating that they were fully complemented by their transgenes (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with control SMC2 KO cells (Hudson et al., 2003) in which both condensin I and II subunits were removed. Addition of doxycycline (which leads to shut-off of the rescue transgene) resulted in cell death for all three cell lines, with SMC2OFF and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cells dying at 24–48 hours of drug treatment. CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) cells showed appreciable cell death after 72 hours in drug.

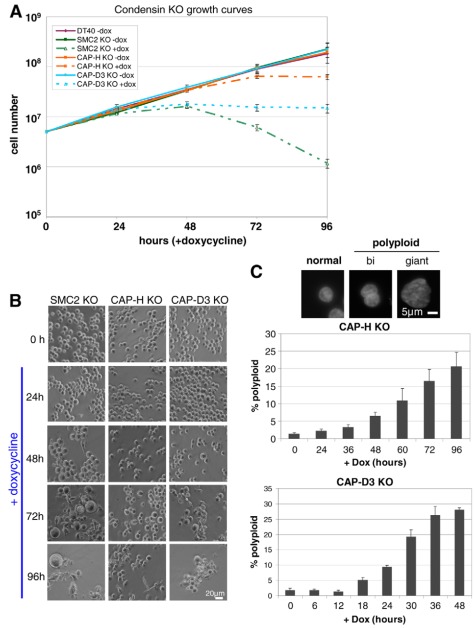

Fig. 2.

Growth analysis of CAP-H and CAP-D3 knockout cell lines. (A) Growth curves of parental DT40 cells and CAP-H and CAP-D3 knockout (KO) cell lines in the presence or absence of doxycycline (dox). (B) Phase-contrast images of SMC2, CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cell lines in the absence or presence of doxycycline for up to 96 hours. (C) Scoring of polyploid cells for condensin KOs. PFA-fixed, DAPI-stained cells counterstained with antibodies against lamin B1 or β-tubulin were used to quantify the amount of binucleate or giant cells (grouped together as polyploid cells) and expressed as a percentage of the total population. Examples of DAPI images of normal-sized, binucleate and giant cells are presented above. Error bars represent the standard error.

SMC2OFF, CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cultures appeared to suffer from defects in cytokinesis, as shown by the appearance of larger cells over the passage of time in doxycycline. This effect was most dramatic for SMC2OFF cells. To quantitate this defect for CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cells, interphase cells were scored as normal or polyploid – the latter either being binucleate, where two nuclei were present or fused in one cytoplasm, or giant cells that appeared as one large nucleus several fold larger than that of diploid cells (Fig. 2B). CAP-D3OFF cells increased in polyploidy from 3 to 10% by 24 hours and to 20% by 30 hours (Fig. 2C). CAP-HOFF cells also showed a similar increase, but were considerably delayed. Of cells scored as polyploid, >90% were binucleate at later time-points, suggesting that CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cells did not proceed generally beyond one failed division.

CAP-D3OFF cells show chromosome bridges in contrast to CAP-HOFF cells

Next, we examined the effects of either CAP-H (condensin I) or CAP-D3 (condensin II) depletion on chromosome morphology and segregation. CAP-HOFF chromosomes appeared wider and puffier, whereas CAP-D3OFF chromosomes were more bent and twisted in appearance (Fig. 3A; see below for a more detailed investigation of chromosome morphology).

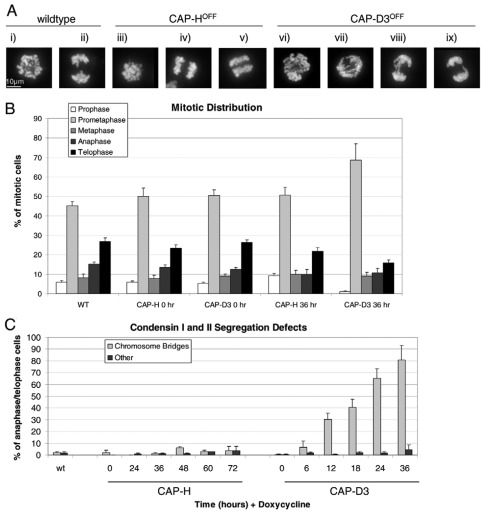

Fig. 3.

Mitotic stage analysis and chromosome segregation defects. (A) PFA-fixed cells stained with DAPI showing metaphase (i, iii and vi) and anaphase cells (ii, iv, v and vii–ix), revealing the presence of chromosome-segregation defects mainly in CAP-D3 knockout (KO) cell lines (vii–ix). (B) Mitotic-stage analysis of wild-type (WT), CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cell lines, with and without doxycycline at 0 and 36 hours (see supplementary material Fig. S3 for a more detailed time-course distribution). PFA-fixed mitotic cells were stained with DAPI and probed with antibodies against phosphoserine 10 histone H3and lamin B1 or INCENP and β-tubulin as cell cycle markers. (C) Chromosome-segregation defect analysis in CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cell lines. The major chromosome-segregation defects visible under PFA fixation and DAPI staining were divided into two categories and scored as a percentage of total anaphase and telophase cells: chromosome bridges and ‘other’ (defined as anaphases with lagging chromosomes or multipolar anaphases with chromosomes separating to more than two spindle poles). Error bars represent the standard error.

Overall, we observed little change in the overall distribution of mitotic phases or mitotic index in CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cultures (supplementary material Figs S3, S4). Importantly, the mitotic distribution of CAP-HON and CAP-D3ON cells was similar to that of the wild-type cells (Fig. 3B; supplementary material Fig. S3), indicating that the CAP-H and CAP-D3 Tet-repressible transgenes fully rescued function. The proportion of prophase cells observed decreased considerably for CAP-D3OFF cells, whereas prophase CAP-HOFF cells increased at 24 hours of doxycycline treatment before decreasing at subsequent time-points. These results suggest that, consistent with previous studies (Gerlich et al., 2006; Hirota et al., 2004), CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cells have a shortened prophase and CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) cells are prolonged in prophase.

CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cultures also showed a moderate accumulation in prometaphase (see supplementary material Fig. S3 for detailed time-course mitotic distribution) and a slight decrease in the number of anaphases and telophases over time, presumably owing to the cells spending more time in prophase, prometaphase and metaphase. The mitotic index did not rise appreciably (supplementary material Fig. S4), consistent with other condensin knockdown studies (Hudson et al., 2003; Ono et al., 2004).

Both CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cultures showed an increased, but still low, level (<5%) of cells showing lagging chromosomes (Fig. 3C). This suggested that kinetochore function was not severely compromised in either mutant. This finding is consistent with electron microscopy and immunofluorescence studies showing normal kinetochore plates (Ribeiro et al., 2009) and normal CENP-C staining of kinetochores in DT40 SMC2 KO cells (Hudson et al., 2003).

In contrast to the above, a striking difference in chromosome bridges was observed between CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cultures undergoing anaphase (Fig. 3C). After as few as 6 hours of doxycycline treatment, CAP-D3OFF cells showed obvious chromosome bridges (see Fig. 3Avii–ix) and, by 36 hours, up to 80% of anaphase and telophase cells displayed prominent bridges (Fig. 3C). These results were similar to those observed in SMC2OFF cells (Vagnarelli et al, 2006), although closer analysis of CAP-D3OFF chromatids revealed a more kinked or bent appearance in early anaphase compared with those in SMC2OFF cells (Fig. 3A and see later). Remarkably, these bridges were not detected in the CAP-HOFF cultures.

CAP-H KO cells fail cytokinesis due to persistence of anaphase fibres

Our failure to observe anaphase bridges in fixed cells depleted of CAP-H (condensin I) was surprising. An RNAi study using HeLa cells described similar defects in anaphase bridges for both condensin I and II knockdowns (Gerlich et al., 2006). Similarly, condensin I RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans produced similar, but weaker, anaphase segregation defects when compared with RNAi of condensin II subunits (Csankovszki, 2009).

Despite our failure to observe dramatic chromatin bridges during anaphase in CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) cultures, our previous analysis had revealed that these cultures undergo an increase in ploidy after doxycycline treatment (Fig. 2C). This suggested that CAP-HOFF cells might fail in cytokinesis as a consequence of a more subtle defect.

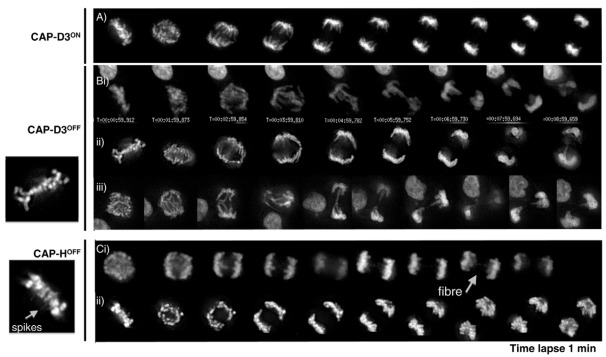

To examine chromosome behaviour in these cell lines at greater resolution and in living cells, we generated CAP-HON/OFF (condensin ION/OFF):H2B–GFP and CAP-D3ON/OFF (condensin IION/OFF):H2B–GFP cell lines and performed live-cell imaging (Fig. 4). Although CAP-D3ON H2B–GFP anaphases appeared normal (Fig. 4A), we readily observed chromatin bridges in all anaphases of CAP-D3OFF:H2B–GFP cells (Fig. 4B) that were reminiscent of those previously observed in SMC2 KO cells (Hudson et al., 2003) and consistent with our microscopy on fixed samples (Fig. 3). By contrast, CAP-HOFF live-cell imaging did not show chromatin bridges but revealed the presence of finer chromatin threads or spikes, both in metaphase, as previously described for SMC2 KO cells (Ribeiro et al., 2009), and also in anaphase (Fig. 4Ci).

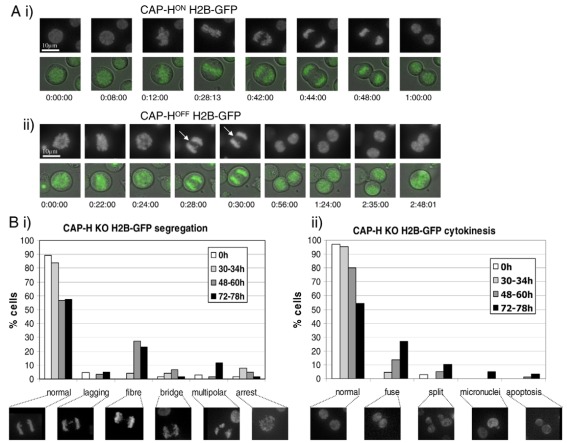

Fig. 4.

Mitotic live-cell imaging analysis. (A) CAP-D3ON cell line. (B) CAP-D3OFF cell line, showing images for three different mitoses (i–iii), with examples of chromatid bridges, and a close-up of metaphase chromosomes shown on the left. (C) CAP-HOFF cell line, showing images for two different mitoses (i,ii), with fine chromatin fibres indicated by arrow, and a close-up of metaphase chromosomes (arrowhead) showing radiating chromatin fibres or ‘spikes’. Both CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cell lines were treated with doxycycline for 30 hours. Live-cell imaging was performed on conditional knockout cell lines containing the transgene encoding H2B–GFP. Images were captured every minute.

Our live-cell imaging analysis of CAP-HON/OFF (condensin ION/OFF):H2B–GFP cells therefore suggested a possible mechanism for the observed increase in ploidy of those cells. For quantification, we analyzed multiple longer-term movies from CAP-HON cells and CAP-HOFF cells 30–34 hours, 48–60 hours and 72–78 hours after addition of doxycycline (Fig. 5). While CAP-HON (condensin ION):H2B–GFP cells proceeded normally through mitosis (Fig. 5Ai), CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF):H2B–GFP cells frequently displayed fine fibre bridges in anaphase whose presence correlated with subsequent cell fusion events (Fig. 5Aii). We observed these fibres in 27% and 22% of anaphases in CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF):H2B–GFP cells at 48–60 and 72–78 hours, respectively (Fig. 5Bi). Importantly, the appearance of the fibres coincided with a marked increase in defects in cytokinesis. The delayed appearance of the anaphase fibres could be linked to the apparent slower turnover of CAP-H, resulting in there being sufficient residual protein present to prevent the appearance of threads (which appeared very localized) until all protein had disappeared after several cell cycles. We note at 48 hours in the presence of doxycycline when no protein could be detected, as judged by western blot analysis (Fig. 1C), a peak in anaphase threads in CAP-HOFF cells was observed. Although we were unable to detect threads consistently using PFA fixation and DAPI staining (Fig. 3), they were preserved under glutaraldehyde fixation at similar levels when observed in live-cell imaging of CAP-HOFF anaphase cells (supplementary material Fig. S5).

Fig. 5.

Live-cell imaging analysis of CAP-H knockout H2B–GFP cell lines. (A) Comparison of CAP-H KO cell line (i) without and (ii) with doxycycline (+ 52 hours). The cell line contains the transgene encoding H2B–GFP. Fluorescence and DIC images are shown for each mitotic series. Note that, in (ii), a thread appears (white arrow) during anaphase, and the daughter cells fuse (last panel) approximately two hours after telophase. These are the two most common segregation and cytokinesis defects in CAP-HOFF cells. (B) Quantitative live-cell analysis of CAP-H KO:H2B–GFP cell line. (i) Chromosome-segregation defects are shown in the following categories: chromosome lagging, chromatin fibre, chromosome bridge, multipolar anaphases and mitotic arrest (representing cells in mitosis for over 2 hours). (ii) Cytokinesis defects are shown in the following categories: cell fusion, split (which represents separated chromatids that undergo a further division during telophase or cytokinesis), micronuclei and apoptosis. Representative images of each defect category are shown below the bar chart. The following numbers of cells or independent movies were scored for each time-point: N=66 (0 hours dox), N=21 (+dox 30–34h), N=49 (+dox 48–60h) and N=31 (+dox 72–78h).

The origin of the threads in CAP-HOFF cells is intriguing as they bear resemblance to PICH- or BLM-coated DNA fibres (Baumann et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2007). Indeed, previous RNAi of PICH results in an accumulation of binculeate cells, similar to the CAP-H KO phenotype (Kurasawa and Yu-Lee, 2010). It will be of interest, therefore, to ascertain whether there are PICH-coated anaphase fibres in CAP-HOFF cells persist as they do in topoisomerase-IIα-depleted cells (Spence et al., 2007) and whether the fibres are of arm, centromeric or telomeric origin.

As predicted by our fixed-cell analysis, cytokinesis defects increased markedly after 48 hours. The most prominent defect was daughter cells fusing back together (in many cases, several hours after anaphase, see Fig. 5Aii,Bii), with fusion occurring in 13% of cells at 48–60 hours and in 27% at 72–78 hours of doxycycline treatment. Other defects observed included (1) cells ‘splitting’, where cells undergo cytokinesis twice but without karyokinesis the second time – with 5% observed at 48–60 hours and 10% at 72–78 hours of doxycycline exposure; (2) a substantial increase in cells with multipolar anaphases, where more than two sets of chromatids were seen migrating to the poles, with 12% observed at 72–78 hours of doxycycline; and (3) a slight increase in cells forming micronuclei.

These results thus far suggest that condensin I and condensin II perform different roles in maintaining chromosome architecture, with condensin II being responsible for large-scale chromosome stability and condensin I providing a more subtle aspect during anaphase.

Metaphase chromosome morphologies of condensin-I- and condensin-II-disrupted cells display contrasting phenotypes

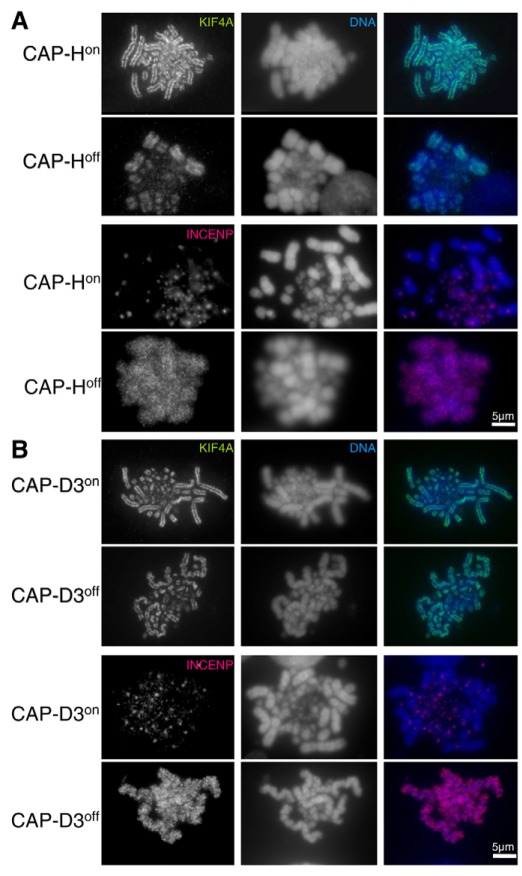

To understand how mitotic chromosomes are affected by depletion of either CAP-H or CAP-D3, we stained chromosome spreads of both CAP-HON/OFF (condensin ION/OFF) and CAP-D3ON/OFF (condensin IION/OFF) cells with antibodies recognising the mitotic scaffold proteins KIF4A and the inner centromere protein INCENP (Fig. 6A,B). As previously observed (Fig. 3), the two KO cell lines displayed distinct chromosome morphologies, with CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) chromosomes becoming short and fuzzy, whereas CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) chromosomes were long, twisted and bent over. These morphologies are broadly consistent with other chromosome-spread analyses of condensin I and II knockdown in vertebrates (Abe et al., 2011; Ono et al., 2003) and also reflect the conclusions of the recent in vitro analysis on assembled chromosomes using varying ratios of condensin I and II from Xenopus egg extracts (Shintomi and Hirano, 2011).

Fig. 6.

Localisation of the chromosomal proteins KIFA and INCENP. (A) Methanol:acetic-acid-fixed CAP-HON and CAP-HOFF metaphase cells immunostained with antibodies against either KIF4A or INCENP. (B) CAP-D3ON and CAP-D3OFF metaphase cells were fixed and stained as above. CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cells were treated with doxycycline for 48 hours. In both cell lines, KIF4A (green) and INCENP (red) are shown in the left column, DNA stained with DAPI (blue) is shown in the middle column, and a merge of DNA and either KIF4A or INCENP is shown in the right column.

The abundant scaffold protein KIF4A remained axial in the absence of both condensin I and II. CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) chromosomes had a more diffuse, wider scaffold staining, whereas CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) chromosomes displayed a tight axial staining that was also bent and twisted in line with the chromosome morphology (Fig. 6A,B, top 2 panels). This contrasted with the distribution of KIF4A in SMC2OFF chromosomes, which lacked condensin altogether. There, KIF4A staining was diffuse, and the axial concentration was lost (Hudson et al., 2008).

Loss of either condensin I or II caused INCENP staining to be lost from inner centromeres, and instead there was diffuse staining of INCENP covering the chromosome arms (Fig. 6A,B, bottom 2 panels). Similar staining has been seen previously in SMC2OFF cells (Hudson et al., 2003). Despite not being localized or enriched at the centromere, INCENP still transferred to the spindle midzone during anaphase in both CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cells (data not shown). The apparently stronger, albeit diffuse, INCENP signal on condensin I compared with condensin II KO metaphase chromosomes probably relates to the more diffuse nature of CAP-HOFF chromatin compared with CAP-D3OFF chromatin.

Studies of vertebrates in vivo using the aurora B inhibitor hesperadin and in vitro data depleting aurora B using a cell-free system both showed disruption of the chromosome passenger complex causing inhibition of loading of condensin I, but not condensin II, onto mitotic chromosomes I (Lipp et al., 2007; Takemoto et al., 2007). These studies and our data suggest that, although only condensin I is dependent on the chromosome passenger complex (CPC) for correct loading onto chromosomes, the CPC requires the action of both condensins for its localisation to the inner centromere of mitotic chromosomes.

It is interesting to note that the CPC initially localizes to chromosome arms but is progressively concentrated in the inner centromeres during prometaphase and metaphase (Ruchaud et al., 2007). It is has been proposed (Yanagida, 2009) that a function of condensin is to clear proteins to prepare for subsequent stages of mitosis, which would fit well with both condensin I and II acting together to clear INCENP from the arms of mitotic chromosomes.

Both condensin-I- and condensin-II-disrupted cells have compromised intrinsic chromosome structure

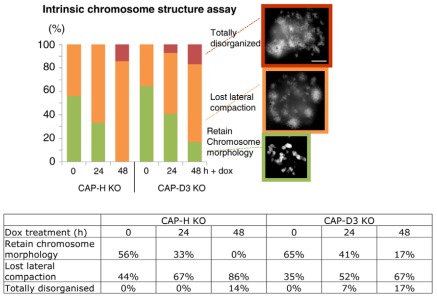

We used our previously developed intrinsic metaphase structure (IMS) assay to probe the functional chromosome architecture in both condensin-I- and condensin-II-depleted cells. This assay exploits the fact that histones neutralise only 60% of the charge on chromosomal DNA. Thus, if divalent cations are removed by addition of EDTA, the negatively charged DNA repels itself, and the chromatin expands into an amorphous mass in which higher-order chromatin structures are disrupted (Earnshaw and Laemmli, 1983; Hudson et al., 2003). Under normal circumstances, protein interactions within the chromosome provide a ‘structural memory’ allowing chromosomes to resume their normal structure once divalent cations are restored. When this assay was applied to SMC2-depleted cells lacking functional condensins I and II, the chromosomes were unable to refold, with chromosomes no longer resuming their characteristic mitotic shape (Hudson et al., 2003).

Both CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) and CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) cells showed defects in intrinsic chromosome structure at 24 and 48 hours after addition of doxycycline (Fig. 7). Only 33% of CAP-H-depleted chromosomes showed recovery of any recognizable structure after 24 hours, and no recovery was observed after 48 hours in doxycycline. Chromosomes in 47% of CAP-D3OFF (condensin IIOFF) mitotic cells recovered their structure in the IMS assay after 24 hours in doxycycline, a time when the segregation defects are close to maximum. By 48 hours, 17% still retained chromosome architecture in the assay.

Fig. 7.

Intrinsic metaphase structure (IMS) assay. Chromosome morphology of TEEN-treated CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cells were grouped into the following categories, ranging from less to more disorganized: ‘retain chromosome morphology’, ‘lost lateral compaction’ and ‘totally disorganized’. Representative images from each category are shown, the data were tabulated below and scored from the following numbers of metaphases: CAP-H 0 hours doxycycline (dox; N=16), CAP-H +dox 24 hours (N=15), CAP-H +dox 48 hours (N=14), CAP-D3 0 hours dox (N=17), CAP-D3 +dox 24 hours (N=27), CAP-D3 +dox 48 hours (N=24). Chromosomes were stained with DAPI (white). All images are at the same scale. Scale bar: 5 μm.

These results suggest that, in either condensin-I- or II-depleted cells, a residual, but weakened, architectural network of protein–protein interactions exists within mitotic chromosomes (in contrast to cells in which both condensins are depleted or in SMC2OFF cells), but the CAP-D3 (condensin-II)-depleted chromosomes retain greater structural memory compared with CAP-H (condensin-I)-depleted mitotic chromosomes.

Ultrastructural analysis of condensin-disrupted chromosomes

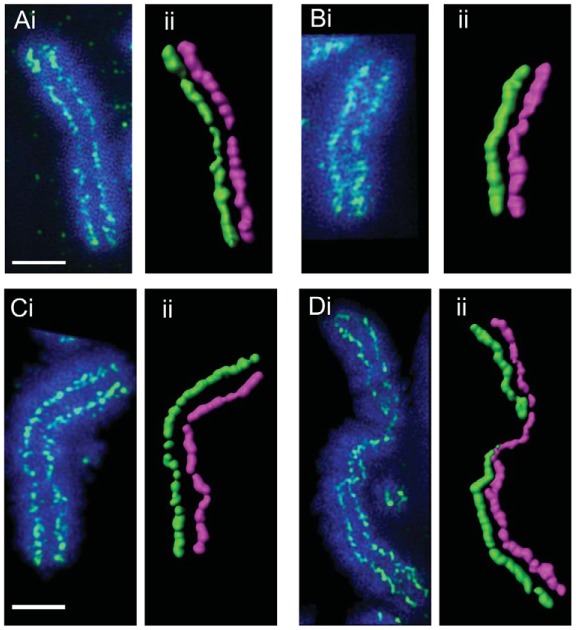

In order to understand the nature of the morphological defect more closely and perform accurate quantification, we examined SMC2OFF, CAP-D3OFF and CAP-HOFF chromosomes using 3D structured illumination microscopy (SIM), a technique that is capable of generating significantly higher-resolution images of metaphase chromosomes compared with those acquired by conventional light microscopy by overcoming the diffraction limit to 104 and 280 nm, for lateral and axial resolutions, respectively (Gustafsson et al., 2008). The high-resolution imaging allowed measurements of the axial and lateral length and width of condensin-disrupted chromosomes in chromosome spreads from CAP-H, CAP-D3 and SMC2 KO cells at 0, 28 and 48 hours in the presence of doxycycline following staining for KIF4A and DNA (supplementary material Fig. S6).

SMC2OFF chromosomes lacking condensin I and II became considerably shorter and wider following 24 hours of doxycycline treatment, as described previously (Hudson et al., 2003). In general, the dimensions of chromosomes lacking CAP-H (condensin I) paralleled those of SMC2 KO chromosomes. CAP-HOFF (condensin IOFF) chromosomes also became shorter and wider following exposure of cells to doxycycline (Fig. 8; supplementary material Fig. S6). For comparable quantitative measurements of chromosome width and length, only chromosome 1 was analysed. By contrast, doxycycline-treated CAP-D3OFF chromosomes became considerably longer and thinner relative to untreated as well as to SMC2OFF and CAP-HOFF chromosomes. These morphological defects increased with longer doxycycline treatment (48 hours) for both CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF cells; no 48-hour time-point was examined for SMC2OFF as cell death was too frequent at this point.

Fig. 8.

Super-resolution microscopy (3D-SIM) analysis of condensin I and II knockout mitotic chromosomes. (A,B) 3D-SIM images of CAP-HON and CAP-HOFF and (C,D) CAP-D3ON and CAP-D3OFF metaphase chromosomes. Methanol:acetic-acid-fixed chromosomes were immunostained with antibodies against KIF4A and counterstained with DAPI. Surface rendering of KIF4A-stained metaphase chromosomes is shown in the images labelled ‘ii’. Each sister chromatid is pseudo-coloured in separate colours in order to highlight the metaphase chromosome scaffold. Scale bars: 2 μm.

Our conventional wide-field images revealed KIF4A staining to be bent and twisted in CAP-D3OFF spreads (Fig. 6). To visualise the pathway of the KIF4A scaffold more closely, we traced the staining from our 3D-SIM images of CAP-HOFF and CAP-D3OFF (doxycycline treated for 28 hours) chromosomes stained for KIF4A (Fig. 8). Consistent with our 3D-SIM measurements of metaphase chromosomes (supplementary material Fig. S6), CAP-HOFF chromosomes displayed KIF4A signals that were wider and shorter relative to those of untreated cells (Fig. 8A,B). Strikingly, we found the KIF4A signals in CAP-D3OFF chromosomes appeared to join together and crossover from one chromatid to another at multiple points along the axis (Fig. 8C,D), which we believe is a function of the twisting and bending of chromatid pairs as a result of CAP-D3 depletion. The amount of bending, twisting and joining of the KIF4A chromatid signal increased at the 48-hour time-point (data not shown). These results highlighted the importance of condensin II in maintaining chromosome rigidity, suggesting that a key role of condensin II is to keep the chromatid axes rigid and straight in readiness for anaphase.

Discussion

Understanding how chromosomes are folded in preparation for cell division remains one of the classic challenges of cell biology. We have generated the first conditional knockouts for condensin I and II subunits CAP-H and CAP-D3 in vertebrate (DT40) cells and performed a quantitative structural analysis of condensin-I- and condensin-II-depleted mitotic chromosomes from these respective KO cell lines. Our study has yielded a number of surprising and important findings.

A key strength of our system is that it is a quick and immediate shutoff with no off-target effects, which we believe has led to such a clear phenotypic distinction between condensin I and II. While there are always going to be caveats for any system, the Tet-OFF system presented here shows a very strong correlation in presentation of phenotype and time in doxycycline for CAP-H and CAP-D3 KOs for defects in both chromosome structure and segregation, and, even at the earliest time-points (i.e. 6 hours in the presence of doxycycline for CAP-D3 KO), the phenotypes appear weaker rather than different.

A key finding obtained by super-resolution microscopy analysis of condensin-II-disrupted chromosomes was that sister chromatid pairs can twist over each other. This finding bears resemblance to the striking phenotype evident in CAP-D3 (HCP-6) RNAi of the holocentric chromosomes of C. elegans (Stear and Roth, 2002). The result in chicken DT40 cells is that chromatid pairs do not align in parallel, and lack of structural rigidity and twisting presumably cause increased tangling of chromatids, leading to formation of chromosome bridges during anaphase. In general, CAP-D3OFF bridges are similar to those observed in SMC2OFF anaphases (Vagnarelli et al., 2006), with a qualification that CAP-D3OFF early-anaphase chromatids are curlier in morphology, consistent with their appearance during metaphase.

A number of studies have suggested that condensin has an essential role in kinetochore structure or function (Bernad et al., 2011; Ono et al., 2004; Samoshkin et al., 2009; Wignall et al., 2003). In opposition to this prevailing view were our previous studies that showed SMC2 is not required for DT40 kinetochores to attach to spindle microtubules and segregate at anaphase despite being necessary for the rigidity of the centromere (Hudson et al., 2003; Vagnarelli et al., 2006; Ribeiro et al., 2009) and several RNAi studies in which kinetochore attachments to microtubules were examined (Gerlich et al., 2006; Jaqaman et al., 2010). Here, two further independent condensin gene knockouts in DT40 cells also failed to yield detectable kinetochore phenotypes. Depletion of either condensin I or condensin II protein causes a mild increase in prometaphases, but no overt mitotic delay, as reflected by an increase in mitotic index. Furthermore, careful examination revealed no substantial increase in the number of lagging chromosomes scored at anaphase, and indeed the cells appeared to die as a result of a failure of late cytokinesis subsequent to the formation of chromatin bridges.

Our study clearly reveals that condensin I and condensin II have nonredundant functions in targeting of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC) to the inner centromere. It has recently been shown that CPC targeting to centromeres occurs as a consequence of the apoptosis inhibitor protein survivin binding to histone H3 phosphorylated on threonine 3 by the serine/threonine-protein kinase haspin (Kelly et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Yamagishi et al., 2010). Our results indicate either that the two condensin complexes have nonredundant functions in targeting haspin or that some other aspect of inner centromere structure dependent on both condensin I and II must contribute to CPC localisation.

Perhaps the greatest surprise from this study came when we showed that, even though the average ratio of condensin I to condensin II in chicken DT40 cells is approximately 10:1 on condensed chromosomes and 2:1 in the cytoplasm of mitotically blocked cells when adjusted for protein weight (Ohta et al., 2010), depletion of CAP-H (condensin I) yields a more subtle phenotype in vivo than does depletion of CAP-D3 (condensin II). Cells lacking either condensin subunit exhibit anaphase bridges, and these apparently result in the ultimate failure of cytokinesis. However, the bridges seen in the absence of condensin II are much more robust and obvious, whereas those seen in the absence of condensin I are highly attenuated and only seen after careful examination. In Xenopus egg extracts, the ratio of condensins I to II has been calculated to be 5:1 (Shintomi and Hirano, 2011) and 1:1 from HeLa nuclear extracts (Ono et al., 2003). Our measurements are based on quantitative proteomics analysis of condensins I and II in DT40 mitotic chromosomes and not from total condensin, although it is also possible there exists some species variation (Ohta et al., 2010).

Paradoxically, if we use a quantitative assay based on the ability of the chromosomal three-dimensional architecture to reform after unravelling of the chromatin, then condensin-I-depleted chromosomes are appreciably more compromised than those depleted of condensin II (Fig. 7). How can it be that structurally compromised chromosomes segregate better at anaphase than those that appear to be structurally more sound?

Chromosome condensation can be viewed as two major events that involve an unknown degree of inter-dependency and overlap: (1) compaction of the chromatin, which we define as the reduction in the volume of the territory occupied by each chromosome from interphase to metaphase and (2) shaping the X-shaped architecture of the mitotic chromosome, which relates to arranging the higher-order structure of compacted chromatin and the process we believe where the condensins exert most influence. Little is known about (1) except that the initial notion of histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation being the crucial catalyst for compaction is not supported by biochemical or genetic data (Adams et al., 2001; Murnion et al., 2001). It is, however, entirely possible that the driver for mitotic chromatin compaction is a combination of posttranslational modifications of the histones and/or other chromosomal proteins (Markaki et al., 2009; Moser and Swedlow, 2011).

In all higher-eukaryotic systems studied, condensin appears to play its most important role in shaping the architecture of mitotic chromosomes. Thus, numerous studies, including our own, find that chromosomes without either condensin I or II or both are still able to achieve the characteristic X-shaped morphology (Belmont, 2006). The two condensin complexes play distinct roles in mitotic chromosome structure. We have shown that, compared with the wild type, CAP-H (condensin-I)-depleted chromosomes are wider laterally and shorter axially, whereas CAP-D3 (condensin-II)-depleted chromosomes are thinner and longer axially, as well as being twisted and bent. In CAP-H (condensin I) KO cells, KIF4A appears to remain concentrated along the chromatid axes, and sister chromatids appear parallel (although wider). This implies that condensin II alone can support mitotic chromosome rigidity, whereas condensin I is clearly not able to do so.

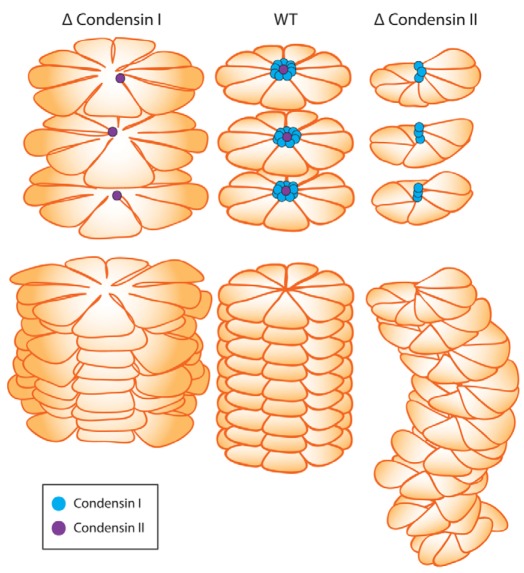

Based on our results and proteomics analysis of mitotic chromosomes showing the substantial enrichment of condensin I over condensin II in DT40 cells (Ohta et al., 2010), we propose a model in which condensin I mediates more-frequent short-range lateral interactions among chromatin loops, whereas condensin II mediates axial stacking of the laterally assembled configurations (Fig. 9). The lateral widening of metaphase chromosomes and the presence of fine unravelled chromatin fibres during anaphase in condensin-I-depleted cells are consistent with the loosening of laterally assembled loops of chromatin. We therefore suggest that condensin I organises short-range chromatin loops by assembling them into higher-order domains (depicted in Fig. 9 as rosettes). Condensin II, which is relatively immobile during mitosis compared with the rapidly exchanging condensin I (Gerlich et al., 2006), might then act as a primary lock of condensed chromatin to connect the rosettes longitudinally and form the rigid chromosome axis.

Fig. 9.

A model displaying the contrasting roles of condensin I and II. Based on proteomics data showing a 10:1 ratio of condensin I to condensin II on mitotic chromosomes (Ohta et al., 2010) and our own results, we propose the following unifying model for condensin I and II function in mitotic chromosomes. The size of condensin I and II reflects the known size relative to DNA based on atomic force measurements (Anderson et al., 2002; Yoshimura et al., 2002). Top panel: individual rosette layers showing localisation of condensin I and II. Bottom: rosette layers stacked together showing the effect on longitudinal axial compaction in the presence and absence of condensins. We propose that, in wild-type mitotic chromosomes, condensin I stabilises and nucleates short-range loops, promoting compaction of chromosome rosettes. Condensin II provides the long-range linkage and alignment between the rosettes, thus facilitating chromosome longitudinal compaction. Chromosomes deficient of condensin I (Δ condensin I) are unable to link and nucleate short-range loops, resulting in a fatter and disorganized chromosome scaffold. Chromosomes deficient of condensin II (Δ condensin II) are unable to provide regular structural linkage between rosettes. Discrete rosettes are unable to form, resulting in a thinner chromosome lacking structural integrity.

Thus, the primary role of condensin II would be to establish the chromosome axis, with condensin I capable of being added or removed, as required. The dynamic behaviour of condensin I would allow chromatin loops to be adjusted, removed or added as the chromosome shape changes, with increasing levels of higher-order folding. Such a dynamic model would be consistent with the existence of chromosome folding intermediates (Kireeva et al., 2004). This flexibility seems to be in agreement with experiments showing a high degree of variation with respect to sequence and spacing possibility, with normal condensation occurring per se even after large amounts of foreign DNA are introduced into vertebrate cells (Strukov et al., 2003).

In the absence of condensin II, chromosomes fail to compact axially, becoming bent and twisted. A long-range or connector role of condensin II could explain this loss of rigidity. We envisage that loss of a vertical stabilizer would allow condensin-I-tethered rosettes to be able to move more freely relative to each other. A consequence of this would be that sister chromatids do not maintain a parallel register. This has serious consequences for chromosome segregation in anaphase. If condensin II acts axially, structuring the ‘backbone’ or scaffold, then lack of condensin II is likely to result in a large-scale entanglement of whole chromosomes at anaphase, as evident in Fig. 4Aii. Alternatively, it might be that functional interactions between condensin II and DNA topoisomerase II are required for topoisomerase II to decatenate sister chromatids efficiently at anaphase. Conversely, if condensin I acts primarily to condense chromatin loops, then depletion might only lead to small-scale entanglement of those loops, leading to the narrow fibres as seen in Fig. 4Ci. Importantly, unlike the twisted condensin-II-depleted chromatids, condensin-I-depleted chromatids still maintain a parallel register despite being structurally compromised, which we believe is a key reason behind the milder anaphase defects. Together, the results of this study highlight the contrasting roles of the two condensin complexes in organizing mitotic chromosomes in vertebrates.

A key outstanding question is whether condensin localises to specific regions of the chromosome or whether condensin and indeed chromosome condensation varies from one cell to another in a non-sequence-dependent fashion. At least at the gross cytological level, there appears to be some predictability of folding, as judged by the reproducible chromosome banding patterns in vertebrates (Hilwig and Gropp, 1972). Studies in yeast (D'Ambrosio et al., 2008) have defined a loose motif to which condensin binds, but whether this translates to higher-eukaryotic systems that contain an additional condensin complex and have much larger chromosomes to fold is yet to be resolved. Our recently generated conditional knockouts and advances in single-molecule imaging and proteomics will help answer these important questions.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The chicken lymphoma B DT40 cell line was cultured as described previously (Buerstedde and Takeda, 1991). SMC2ON/OFF cells were grown as described elsewhere (Hudson et al., 2003). For repression of tetracycline-repressible genes, cells were cultured in 200 ng ml−1 doxycycline.

Production of CAP-H and CAP-D3 conditional KO cell lines

PCR primers for the amplification of genomic homology arms were designed using the May 2006 assembly of the chicken reference genome. Homology arms were PCR amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and cloned into the appropriate antibiotic resistance plasmid vector. For cDNA rescue constructs, cDNA was generated from DT40 RNA and cloned into pGEM-T Easy and sequenced for verification.

To generate tetracycline-repressible constructs encoding GgCAP-H and GgCAP-D3, the cDNAs were cloned into SacII and Klenow-filled EcoRI sites in the pUHD 10.3 vector. To distinguish between endogenous and Tet-repressible CAP-H and CAP-D3, primers were constructed that specifically recognized the 5′ TATA box (5′-GCAGAGCTCGTTTAGTGAACCGTCAGATCG-3′) and 3′ poly-A tail (5′-TTTTCACTGCATTCTAGTTGTGGTTTGTCC-3′) from pUHD. These primers were used in conjunction with CAP-H-specific 5′-CTGCCTGGGCGCCGTAGAGC-3′ (TATA); 5′-GTGGAGAAACAGAGTGACACATCAGTGG-3′ and CAP-D3-specific 5′-GTTTTCAACAAACAAGCGCCAGATATTCCC-3′ (TATA); 5′-TCAGTTACATCAGCTTGACACACACACC-3′ primers to recognise the CAP-H or CAP-D3 exogenous transcripts. mRNA was isolated from clones that had been simultaneously cultured in both the presence and absence of doxycycline prior to cDNA conversion and PCR amplification.

GgCAP-H is located on chromosome 22. Although the chicken genome is published online, many contig gaps are still present. As a consequence, the CAP-H genomic sequence is not available on a single file, and there is a sequence gap in the middle of the gene. The CAP-H 5′ arm is 2.6 kb in length, ending 24 bp upstream on the start codon ATG, whereas the 3′ arm is 4.2 kb in size, beginning at coding base 1266 and ending at 2022, deleting 1265 coding bases.

The forward and reverse CAP-H KO arm primers used for the 5′ arm were: 5′-AATGAGAGAGGCTGAGCATGGG-3′; 5′-GAGCGGCTGTTTTGTTTCCC-3′ and for the 3′ arm were: 5′-GGATGTTGACTTTGAGGCATATTTCCGTAAGACC-3′; 5′-TCACAATGACATCAGACAGG-3′.

GgCAP-D3 is located on chromosome 24. The CAP-D3 5′ arm is 2.6 kb in length, extending through the first 567 translated bases, whereas the 3′ arm is 3.8 kb in size, beginning at coding base 985 and ending in an intron between coding bases 1615 and 1616, deleting 630 coding bases.

The forward and reverse CAP-D3 KO arm primers used for the 5′ arm were: 5′-GCCTTCGAACCTCAGTGAG-3′; 5′-ATCCCATCCCACAGCAGTC-3′ and for the 3′ arm were: 5′-GCTGTGATCAGTGCCAGGAATC-3′; 5′-GAAAGCTTTCAATAGAGAAGATAGG-3′.

CAP-H and CAP-D3 5′ and 3′ homologous arms were cloned into the pBlueScript (SK-) vector, in the KpnI, ClaI for CAP-H 5′, SpeI, SacII for CAP-H 3′ and EcoRI for CAP-D3 5′, SpeI and XbaI sites to clone the CAP-D3 3′ arm. Puromycin-, hygromycin- or histidinol dehydrogenase-resistant cassettes driven by the chicken β-actin promoter were inserted in between the 5′ and 3′ arms into the SmaI (CAP-H) or EcoRI, SpeI (CAP-D3) sites.

CAP-H and CAP-D3 gene targeting homology arms and external Southern probes were generated using PCR amplification on DT40 genomic DNA. CAP-H and CAP-D3 cDNA for Tet-repressible rescue vectors was isolated from DT40 RNA. Transfections of CAP-H and CAP-D3 targeting and rescue vectors were performed as described previously (Hudson et al., 2003), with the following modifications. DT40 cells have three copies of the CAP-D3 gene, necessitating three targeting vectors and therefore three rounds of targeting to remove all endogenous copies. CAP-H is diploid, requiring two targeting vectors. Both genes were targeted until one allele remained before insertion of rescue vectors. CAP-H+/− and CAP-D3+/−/− cell lines were co-transfected with CAP-H rescue construct and CMVtTA3 (Gossen and Bujard, 1992), or CAP-D3 rescue construct and ScIItTA3 (Samejima et al., 2008), respectively. Rescue vector expression in the disrupted CAP-H and CAP-D3 cells was analysed using RT-PCR.

Generation of the antibody against CAP-D3

A CAP-D3 fragment comprising residues M1–R260 was cloned into the pGEX-2T vector (GE Healthcare). Recombinant protein was expressed in the Rosetta (DE3) pLysS (Novagen) Escherichia coli strain for four hours at 37°C. The insoluble protein product was purified by SDS-PAGE separation using 8% acrylamide and visualised using 0.5% Coomassie dissolved in water. The recombinant protein band was excised from the gel and sent to the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (Adelaide, Australia) for rabbit polyclonal antibody production.

Immunoblotting

106 cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and processed as described previously (Hudson et al., 2003). The following antibodies and dilutions were used: rabbit anti-ScII (SMC2) (Saitoh et al., 1994) (1:1000), rabbit anti-CAP-D2 (Hudson et al., 2008) (1:1000), rabbit anti-CAP-H (Vagnarelli et al., 2006) (1:2500), rabbit anti-CAP-D3 (1:2500), mouse anti-β-tubulin (Roche; 1:5000), goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (Millipore; 1:60,000) and rabbit anti-mouse HRP conjugate (DAKO; 1:50,000).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

DT40 clone 18 cells were probed with chicken BAC clone CH261-121B2, which completely spanned the genomic CAP-D3 locus. Wild-type DT40 cells were treated with colcemid for two hours before being fixed in ice-cold methanol acetic acid and dropped onto glass slides. Chromosome spreads were dried, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed, as described previously (Pertile et al., 2009).

Chromosome immunofluorescence

Mitotic chromosome spreads and immunofluorescence were performed as described previously (Earnshaw et al., 1989). The following antibodies and dilutions were used: rabbit anti-ScII (SMC2; 1:200), rabbit anti-CAP-D2 (1:200), (Hudson et al., 2008), rabbit anti-CAP-H (1:200) (Vagnarelli et al., 2006), rabbit anti-CAP-D3 (1:200), rabbit anti-Kif4a (1:400) (Samejima et al., 2008), rabbit anti-INCENP (Cooke et al., 1987) (1:400), rabbit anti-TopoIIα (Gasser et al., 1986) (1:1000), donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) (1:600) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen; 1:600). The intrinsic metaphase structure assay (Fig. 7), was performed as described previously (Hudson et al., 2003).

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes and washed with PBS and Tween 20 before being incubated in 1% BSA and 0.15% triton X-100 in PBS (PBS-BT) for 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in primary antibody: rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 S10 (Cell Signaling; 1:1200), anti-tubulin FITC conjugated (Abcam; 1:200), rabbit anti-INCENP (1:400) and mouse anti-lamin B (Abcam; 1:400). Cells were washed in PBS-T and incubated for a further 30 minutes at 37°C with secondary antibodies at 1:200: donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-mouse Texas Red (Jackson). They were then washed in PBS-T before being mounted with VectaShield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

Glutaraldehyde fixation of mitotic chromosomes

DT40 wild-type, CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cells grown on coverslips were blocked in mitosis using colcemid for two hours at a concentration of 100 ng ml−1. Glutaraldehyde was then added directly to the media to a final concentration of 2.5% and allowed to fix for five minutes, before replacing with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. VectaShield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) was used to mount the slides, and images were processed as described below.

Live-cell imaging

CAP-H and CAP-D3 KO cells expressing H2B–GFP were used for the analyses of mitotic progression. Cells were analysed using a time-lapse of 1 or 2 minutes and optical axis integration (OAI) mode on a DeltaVision widefield deconvolution microscope (Applied Precision) equipped with an environmental control chamber. The handling and imaging of cells were performed as described previously (Vagnarelli et al., 2006).

Super-resolution microscopy

For three-dimensional structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM), DT40 wild-type and knockout cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol:acetic acid (3:1) and dropped onto glass slides. Indirect immunofluorescence was carried out as described above. 3D-SIM images were captured on a DeltaVision OMX V3 Imaging System (Applied Precision) using a ×100 1.4-NA UPlanSApo oil-immersion objective lens (Olympus) and immersion oil with refractive index of 1.516. Images were acquired with a Z step-size of 125 nm.

Image analysis

Wide-field fluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Imager.M1 microscope and processed using AxioVision 4.7 (Zeiss). For 3D-SIM microscopy, images were reconstructed using DeltaVision SoftWorX4.1 (Applied Precision). Chromosome dimensions were measured using ImageJ, and 3D surface-rendered images were created using IMARIS (Bitplane). For live-cell microscopy, images were deconvolved using DeltaVision softWoRx 4.1 and displayed as 2D projections.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cameron Nowell for image processing and analysis of 3D-SIM chromosomes, and Alison Graham for metaphase FISH preparation and analysis.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council discovery project [grant number DP110100784 to D.F.H., K.H.A.C. and W.C.E.]; National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grants [APP1030358 and 546454]; an NHMRC RD Wright Fellowship to P.K.; an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship to C.B.W.; an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship to K.H.A.C.; and by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. W.C.E. is a Principal Research Fellow of the Wellcome Trust. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.097790/-/DC1

References

- Abe S., Nagasaka K., Hirayama Y., Kozuka-Hata H., Oyama M., Aoyagi Y., Obuse C., Hirota T. (2011). The initial phase of chromosome condensation requires Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation of the CAP-D3 subunit of condensin II. Genes Dev. 25, 863-874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. R., Maiato H., Earnshaw W. C., Carmena M. (2001). Essential roles of Drosophila inner centromere protein (INCENP) and aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction, and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 153, 865-880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph K. W., Cheng S. M., Paulson J. R., Laemmli U. K. (1977). Isolation of a protein scaffold from mitotic HeLa cell chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 4937-4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. E., Losada A., Erickson H. P., Hirano T. (2002). Condensin and cohesin display different arm conformations with characteristic hinge angles. J. Cell Biol. 156, 419-424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron U., Gossen M., Bujard H. (1997). Tetracycline-controlled transcription in eukaryotes: novel transactivators with graded transactivation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2723-2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann C., Korner R., Hofmann K., Nigg E. A. (2007). PICH, a centromere-associated SNF2 family ATPase, is regulated by Plk1 and required for the spindle checkpoint. Cell 128, 101-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont A. S. (2006). Mitotic chromosome structure and condensation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 632-638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernad R., Sanchez P., Rivera T., Rodriguez-Corsino M., Boyarchuk E., Vassias I., Ray-Gallet D., Arnaoutov A., Dasso M., Almouzni G., et al. (2011). Xenopus HJURP and condensin II are required for CENP-A assembly. J. Cell Biol. 192, 569-582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstedde J. M., Takeda S. (1991). Increased ratio of targeted to random integration after transfection of chicken B cell lines. Cell 67, 179-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. L., North P. S., Hickson I. D. (2007). BLM is required for faithful chromosome segregation and its localization defines a class of ultrafine anaphase bridges. EMBO J. 26, 3397-3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke C. A., Heck M. M., Earnshaw W. C. (1987). The inner centromere protein (INCENP) antigens: movement from inner centromere to midbody during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 105, 2053-2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csankovszki G. (2009). Condensin function in dosage compensation. Epigenetics 4, 212-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csankovszki G., Petty E. L., Collette K. S. (2009). The worm solution: a chromosome-full of condensin helps gene expression go down. Chromosome Res. 17, 621-635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio C., Schmidt C. K., Katou Y., Kelly G., Itoh T., Shirahige K., Uhlmann F. (2008). Identification of cis-acting sites for condensin loading onto budding yeast chromosomes. Genes Dev. 22, 2215-2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dej K. J., Ahn C., Orr-Weaver T. L. (2004). Mutations in the Drosophila condensin subunit dCAP-G: defining the role of condensin for chromosome condensation in mitosis and gene expression in interphase. Genetics 168, 895-906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw W. C., Laemmli U. K. (1983). Architecture of metaphase chromosomes and chromosome scaffolds. J. Cell Biol. 96, 84-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw W. C., Ratrie H., 3rd, Stetten G. (1989). Visualization of centromere proteins CENP-B and CENP-C on a stable dicentric chromosome in cytological spreads. Chromosoma 98, 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzio T. G., Panning B. (2010). Condensin complexes regulate mitotic progression and interphase chromatin structure in embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 188, 491-503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov Y., Anderson E. M., Birmingham A., Reynolds A., Karpilow J., Robinson K., Leake D., Marshall W. S., Khvorova A. (2006). Off-target effects by siRNA can induce toxic phenotype. RNA 12, 1188-1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser S. M., Laroche T., Falquet J., Boy de la Tour E., Laemmli U. K. (1986). Metaphase chromosome structure. Involvement of topoisomerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 188, 613-629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich D., Hirota T., Koch B., Peters J. M., Ellenberg J. (2006). Condensin I stabilizes chromosomes mechanically through a dynamic interaction in live cells. Curr. Biol. 16, 333-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M., Bujard H. (1992). Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5547-5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann P. L., Knust T. (2009). Dynamics of the bacterial SMC complex and SMC-like proteins involved in DNA repair. Chromosome Res. 17, 265-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson M. G., Shao L., Carlton P. M., Wang C. J., Golubovskaya I. N., Cande W. Z., Agard D. A., Sedat J. W. (2008). Three-dimensional resolution doubling in wide-field fluorescence microscopy by structured illumination. Biophys. J. 94, 4957-4970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom K. A., Holmes V. F., Cozzarelli N. R., Meyer B. J. (2002). C. elegans condensin promotes mitotic chromosome architecture, centromere organization, and sister chromatid segregation during mitosis and meiosis. Genes Dev. 16, 729-742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilwig I., Gropp A. (1972). Staining of constitutive heterochromatin in mammalian chromosomes with a new fluorochrome. Exp. Cell Res. 75, 122-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. (2005). SMC proteins and chromosome mechanics: from bacteria to humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360, 507-514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., Mitchison T. J. (1994). A heterodimeric coiled-coil protein required for mitotic chromosome condensation in vitro. Cell 79, 449-458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., Kobayashi R., Hirano M. (1997). Condensins, chromosome condensation protein complexes containing XCAP-C, XCAP-E and a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Barren protein. Cell 89, 511-521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T., Gerlich D., Koch B., Ellenberg J., Peters J. M. (2004). Distinct functions of condensin I and II in mitotic chromosome assembly. J. Cell Sci. 117, 6435-6445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. F., Vagnarelli P., Gassmann R., Earnshaw W. C. (2003). Condensin is required for nonhistone protein assembly and structural integrity of vertebrate mitotic chromosomes. Dev. Cell 5, 323-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. F., Ohta S., Freisinger T., Macisaac F., Sennels L., Alves F., Lai F., Kerr A., Rappsilber J., Earnshaw W. C. (2008). Molecular and genetic analysis of condensin function in vertebrate cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3070-3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. F., Marshall K. M., Earnshaw W. C. (2009). Condensin: Architect of mitotic chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 17, 131-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaqaman K., King E. M., Amaro A. C., Winter J. R., Dorn J. F., Elliott H. L., McHedlishvili N., McClelland S. E., Porter I. M., Posch M., et al. (2010). Kinetochore alignment within the metaphase plate is regulated by centromere stiffness and microtubule depolymerases. J. Cell Biol. 188, 665-679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. E., Ghenoiu C., Xue J. Z., Zierhut C., Kimura H., Funabiki H. (2010). Survivin reads phosphorylated histone H3 threonine 3 to activate the mitotic kinase Aurora B. Science 330, 235-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva N., Lakonishok M., Kireev I., Hirano T., Belmont A. S. (2004). Visualization of early chromosome condensation: a hierarchical folding, axial glue model of chromosome structure. J. Cell Biol. 166, 775-785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurasawa Y., Yu-Lee L. Y. (2010). PICH and co-targeted Plk1 coordinately maintain prometaphase chromosome arm architecture. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1188-1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp J. J., Hirota T., Poser I., Peters J. M. (2007). Aurora B controls the association of condensin I but not condensin II with mitotic chromosomes. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1245-1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima K., Laemmli U. K. (2003). A two-step scaffolding model for mitotic chromosome assembly. Dev. Cell 4, 467-480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markaki Y., Christogianni A., Politou A. S., Georgatos S. D. (2009). Phosphorylation of histone H3 at Thr3 is part of a combinatorial pattern that marks and configures mitotic chromatin. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2809-2819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser S. C., Swedlow J. R. (2011). How to be a mitotic chromosome. Chromosome Res. 19, 307-319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnion M. E., Adams R. R., Callister D. M., Allis C. D., Earnshaw W. C., Swedlow J. R. (2001). Chromatin-associated protein phosphatase 1 regulates aurora-B and histone H3 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26656-26665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S., Bukowski-Wills J. C., Sanchez-Pulido L., Alves Fde L., Wood L., Chen Z. A., Platani M., Fischer L., Hudson D. F., Ponting C. P., et al. (2010). The protein composition of mitotic chromosomes determined using multiclassifier combinatorial proteomics. Cell 142, 810-821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira R. A., Coelho P. A., Sunkel C. E. (2005). The condensin I subunit Barren/CAP-H is essential for the structural integrity of centromeric heterochromatin during mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8971-8984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T., Losada A., Hirano M., Myers M. P., Neuwald A. F., Hirano T. (2003). Differential contributions of condensin I and condensin II to mitotic chromosome architecture in vertebrate cells. Cell 115, 109-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T., Fang Y., Spector D. L., Hirano T. (2004). Spatial and temporal regulation of Condensins I and II in mitotic chromosome assembly in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3296-3308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson J. R., Laemmli U. K. (1977). The structure of histone-depleted metaphase chromosomes. Cell 12, 817-828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertile M. D., Graham A. N., Choo K. H., Kalitsis P. (2009). Rapid evolution of mouse Y centromere repeat DNA belies recent sequence stability. Genome Res. 19, 2202-2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro S. A., Gatlin J. C., Dong Y., Joglekar A., Cameron L., Hudson D. F., Farr C. J., McEwen B. F., Salmon E. D., Earnshaw W. C., et al. (2009). Condensin regulates the stiffness of vertebrate centromeres. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2371-2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C. (2007). Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 798-812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh N., Goldberg I. G., Wood E. R., Earnshaw W. C. (1994). ScII: an abundant chromosome scaffold protein is a member of a family of putative ATPases with an unusual predicted tertiary structure. J. Cell Biol. 127, 303-318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima K., Ogawa H., Cooke C. A., Hudson D. F., Macisaac F., Ribeiro S. A., Vagnarelli P., Cardinale S., Kerr A., Lai F., et al. (2008). A promoter-hijack strategy for conditional shutdown of multiply spliced essential cell cycle genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2457-2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoshkin A., Arnaoutov A., Jansen L. E., Ouspenski I., Dye L., Karpova T., McNally J., Dasso M., Cleveland D. W., Strunnikov A. (2009). Human condensin function is essential for centromeric chromatin assembly and proper sister kinetochore orientation. PLoS ONE 4, e6831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvidou E., Cobbe N., Steffensen S., Cotterill S., Heck M. M. (2005). Drosophila CAP-D2 is required for condensin complex stability and resolution of sister chromatids. J. Cell Sci 118, 2529-2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintomi K., Hirano T. (2011). The relative ratio of condensin I to II determines chromosome shapes. Genes Dev. 25, 1464-1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui N. U., Rusyniak S., Hasenkampf C. A., Riggs C. D. (2006). Disruption of the Arabidopsis SMC4 gene, AtCAP-C, compromises gametogenesis and embryogenesis. Planta 223, 990-997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence J. M., Phua H. H., Mills W., Carpenter A. J., Porter A. C., Farr C. J. (2007). Depletion of topoisomerase IIalpha leads to shortening of the metaphase interkinetochore distance and abnormal persistence of PICH-coated anaphase threads. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3952-3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stear J. H., Roth M. B. (2002). Characterization of HCP-6, a C. elegans protein required to prevent chromosome twisting and merotelic attachment. Genes Dev. 16, 1498-1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strukov Y. G., Wang Y., Belmont A. S. (2003). Engineered chromosome regions with altered sequence composition demonstrate hierarchical large-scale folding within metaphase chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 162, 23-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunnikov A. V., Hogan E., Koshland D. (1995). SMC2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene essential for chromosome segregation and condensation, defines a subgroup within the SMC family. Genes Dev. 9, 587-599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto A., Murayama A., Katano M., Urano T., Furukawa K., Yokoyama S., Yanagisawa J., Hanaoka F., Kimura K. (2007). Analysis of the role of Aurora B on the chromosomal targeting of condensin I. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 2403-2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagnarelli P., Hudson D. F., Ribeiro S. A., Trinkle-Mulcahy L., Spence J. M., Lai F., Farr C. J., Lamond A. I., Earnshaw W. C. (2006). Condensin and Repo-Man-PP1 co-operate in the regulation of chromosome architecture during mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1133-1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov A., Mascarenhas J., Andrei-Selmer C., Ulrich H. D., Graumann P. L. (2003). A prokaryotic condensin/cohesin-like complex can actively compact chromosomes from a single position on the nucleoid and binds to DNA as a ring-like structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5638-5650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. J., Carlton P. M., Golubovskaya I. N., Cande W. Z. (2009). Interlock formation and coiling of meiotic chromosome axes during synapsis. Genetics 183, 905-915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Dai J., Daum J. R., Niedzialkowska E., Banerjee B., Stukenberg P. T., Gorbsky G. J., Higgins J. M. (2010). Histone H3 Thr-3 phosphorylation by Haspin positions Aurora B at centromeres in mitosis. Science 330, 231-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrin E., Legagneux V. (2005). Contribution of hCAP-D2, a non-SMC subunit of condensin I, to chromosome and chromosomal protein dynamics during mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 740-750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wignall S. M., Deehan R., Maresca T. J., Heald R. (2003). The condensin complex is required for proper spindle assembly and chromosome segregation in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 161, 1041-1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Honda T., Tanno Y., Watanabe Y. (2010). Two histone marks establish the inner centromere and chromosome bi-orientation. Science 330, 239-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida M. (2009). Clearing the way for mitosis: is cohesin a target? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 489-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S. H., Hizume K., Murakami A., Sutani T., Takeyasu K., Yanagida M. (2002). Condensin architecture and interaction with DNA: regulatory non-SMC subunits bind to the head of SMC heterodimer. Curr. Biol. 12, 508-513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]