CD1d expression by dendritic cells is dispensable for NKT cell-enhanced antibody responses, but is required for NKT cell-enhanced CD8+ T cell responses.

Keywords: antibody, α-galactosylceramide, antigen presentation, adaptive immunity

Abstract

CD1d-restricted type I NKT cells provide help for specific antibody production. B cells, which have captured and presented a T-dependent, antigen-derived peptide on MHC class II and CD1d-binding glycolipid α-GC on CD1d, respectively, activate Th and NKT cells to elicit B cell help. However, the role of the DC CD1d in humoral immunity remains unknown. We therefore constructed mixed bone marrow chimeras containing CD1d-expressing, DTR-transgenic DCs and CD1d+ or CD1d− nontransgenic DCs. Following DT-mediated DC ablation and immunization, we observed that the primary and secondary antibody responses were equivalent in the presence of CD1d+ and CD1d− DCs. In contrast, a total ablation of DCs delayed the primary antibody response. Further experiments revealed that depletion of CD1d+ DCs blocked in vivo expansion of antigen-specific cytotoxic (CD8+) T lymphocytes. These results provide a clear demonstration that although CD1d expression on DCs is essential for NKT-enhanced CD8+ T cell expansion, it is dispensable for specific antibody production.

Introduction

In recent years, CD1d-restricted type I NKT cells have emerged as regulators of innate and adaptive immunity [1, 2]. Type I NKT cells are T lymphocytes that express homologous invariant Vα14-Jα18 and Vα24-Jα18 TCR chains in mice and humans, respectively [3–5]. The invariant TCR-α chains are paired with a limited set of Vβ chains and are thus, termed as semi-invariant TCR, which recognizes endogenous or exogenous lipid antigens presented by the MHC class I-like molecule CD1d [3–5]. Type II NKT cells express diverse TCRs and recognize self antigens including sulfatide, which binds CD1d [3–5]. The glycolipid molecule α-GC has been shown to promote innate and adaptive immunity via type I NKT cell activation when coadministered with T-dependent antigen [1, 6]. Within 2–4 h of activation, type I NKT cells produce large amounts of IL-4 and IL-13 (promoting Th2 immunity) and IFN-γ (promoting Th1 immunity) and thus, facilitate in vivo priming of antigen-specific Th1 or Th2 immunity [6–8].

In mice with intact type I and type II NKT cells, α-GC induces enhanced primary and recall antibody titers, as well as the development of long-lived plasma cells [9–11]. The α-GC adjuvant is unable to enhance B cell responses in the absence of CD1d expression or type I NKT cells [12–15]. The mechanism by which α-GC stimulates enhanced antibody responses is incompletely understood. We reported previously that the BCR on CD1d-transfected IIA1.6 cells could capture complexes containing α-GC and present them on CD1d to NKT hybridomas, suggesting a role for CD1d expression on B cells [16]. We and other have since shown that CD1d expressed by B cells is necessary for α-GC-enhanced antibody responses [12–15, 17, 18]. We have also shown that CD1d expression shapes B cell memory [11]. Further studies have also led to debate regarding whether additional cognate interactions between B cells and NKT cells are required for α-GC-enhanced antibody responses [18–21]. However, none of these studies considered a role for other CD1d-expressing APCs, including DCs, in regulating antibody responses.

DCs are characterized by highly efficient uptake and proteolytic processing of protein antigen into MHC-binding peptides [22]. Presentation of MHC/peptide complexes to the TCR, expressed by classical CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, is instrumental in their activation and differentiation into effector cells [23]. CD1d+ DCs can also present CD1d/α-GC complexes to the TCR expressed by NKT cells, leading to activation and prolonged IFN-γ production [24, 25]. Furthermore, DC-activated NKT cells can stimulate the functional maturation of DCs in vivo, further increasing their capacity to stimulate CD8+ T cell activation and expansion [26–30]. Thus, NKT-matured DCs have an enhanced capacity to prime antigen-specific T cells (CD4/CD8) and to promote vaccine responses that enhance protective CTL responses [26–29]. In addition to the CD1d/α-GC-dependent mode of activation, NKT cells can be activated by a combination of proinflammatory cytokines [19, 20], by stimulation of TLR4 on DCs [31], and by endogenous antigens presented by CD1d [32, 33].

In this study, we have investigated the contribution of DC CD1d antigen presentation to NKT cell-enhanced B cell and CD8+ T cell responses. We used the transgenic CD11c-DTR mouse model, which allows for short-term ablation of DCs in vivo. A single injection of DT to transgenic mice, which express the primate DTR under control of the DC-specific CD11c promoter, results in ablation of CD11c+ DCs [30]. However, complete ablation of DCs was not desirable for these studies, as a direct, functional comparison of CD1d+ and CD1d− DCs in the presence of other CD1d+ APCs was required. We therefore generated mixed bone marrow chimeras, in which DCs do or do not express CD1d following treatment with DT. These chimeras were tested for antigen-specific B cell responses and in vivo CD8+ T cell expansion. Our results demonstrate that CD1d antigen presentation by DCs is not essential for NKT-enhanced B cell responses but is required for NKT-enhanced CD8+ T cell responses. These findings indicate the possibility that the type of adaptive-immune response potentiated by NKT cells is driven by the type of APCs with which they interact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The following reagents were purchased: LPS-free OVA protein (EndoGrade, Hyglos, Regensburg, Germany), DT (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ, USA), LPS-free, sterile PBS (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany), NP-KLH (Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA, USA), HRP-conjugated anti-IgG1 (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA), fluorochrome-conjugated mAb (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA, and eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), FcγR-blocking mAb 2.4G2 (Bio Express, West Lebanon, NH, USA), Liberase DL (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), DNase1 (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), CFSE and 7-AAD (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), Pro5-MHC Pentamer H2-Kb OVA257–264 (ProImmune, Oxford, UK), and antigen-specific magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). α-GC was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA, USA). The purity, structural integrity, and functionality of α-GC have been described by us previously [16]. PBS57-loaded and unloaded CD1d tetramers were provided by the NIAID Tetramer Facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice (CD45.2- and CD45.1-congenic) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA). Breeding pairs of B6.FVB-Tg Itgax-DTR/EGFP 57Lan/J Diphtheria Toxin Receptor (DTR) mice on a homogenous C57BL/6 (CD45.2) genetic background were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred in-house. The “DTR” offspring were genotyped using DNA isolated from tail-snips and published primer sequences [34]. The DTR mice express the transgene encoding for the simian DTR-GFP fusion protein, which is regulated under the control of the CD11c promoter [34]. CD1d−/− mice, originally a gift from Dr. Mark Exley (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) and lacking all NKT cells, were maintained in the barrier facility at OUHSC (Oklahoma City, OK, USA). The RAG2/OT-1 (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA) carries a transgene that encodes a TCR (Vα2-Jα26 and Vβ5-Dβ2-Jβ2.6) specific for a chicken OVA peptide fragment OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL), presented by the MHC class I molecule H2-Kb. These mice are deficient in the RAG2 and therefore, do not develop mature T or B cells expressing endogenous TCRs, and virtually all peripheral CD8+ cells express the transgene [35]. All experiments, unless indicated otherwise, were commenced on mice at 6–10 weeks of age. All procedures reported herein were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at OUHSC.

Cell-culture media and buffers

DPBS, HBSS (calcium/magnesium-free), and RPMI 1640 were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA, USA). All cells were cultured in RP10 media [RPMI-1640 media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA)], 1× antibiotic-antimycotic, 2 mM glutamax, 10 mM nonessential amino acids, 10 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 mM 2-ME (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Isolation of cells

Spleens were harvested into cold HBSS and a single-cell suspension obtained by mechanical disruption. Alternatively, for DC isolation, spleens were cut into small pieces and incubated in HBSS containing 0.5 mg/ml Liberase DL and 1 μg/ml DNase I at 37°C for 30 min before passing through a 70-μm cell strainer to obtain single-cell suspensions. Bone marrow cells were flushed from the tibias and fibulas using a 25-gauge needle and syringe-filled with cold HBSS. Spleen and bone marrow cell suspensions were washed two times with wash buffer (DPBS containing 5 mM EDTA), and erythrocytes were removed by incubation with ACK lysis buffer (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) for 2 min at 37°C. After washing in wash buffer, cell viability was confirmed as >98% by Trypan blue exclusion, and cells were enumerated using a cell counter (Nexelcom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA).

Generation of bone marrow chimera mice

Naïve, 6-week-old, female C57BL/6 CD45.1 congenic mice were irradiated (700 Rad) and rested for 18 h before a second irradiation (500 Rad). A 137Cs Gamma Cell 40 (Nordion International, Ontario, Canada) was used as the ionizing radiation source. After a further 4 h, a total of 2.5 million donor bone marrow cells (all expressing the CD45.2 allele) was transferred by the i.v. route to the irradiated recipients. For mixed chimeras, donor bone marrow cells consisted of the following 50:50 mixtures: C57BL/6:DTR and CD1d−/−:DTR, whereas single chimeras were produced by transferring 100% DTR bone marrow cells. Recipient mice were then housed for a period of 12 weeks. Mice were euthanized or immunized and subsequently, bled as described. Euthanized mice were used as a source of cells for analysis of re-engraftment of the bone marrow, reconstitution of the lymphoid and myeloid compartments in the periphery, and in vitro functional assays.

DT treatment of DTR mice

DTR or reconstituted chimeric mice were injected i.p. with DT suspended in sterile, LPS-free PBS (4 ng DT/g body weight). The control mice were given sterile LPS-free PBS alone as vehicle. Prior to undertaking the experiments described herein, the efficacy of DC depletion was examined using flow cytometry in a group of DTR mice. For experiments with chimera, we used two doses of DT. The first dose was administered 24 h before immunization and the second dose was administered 24 h after.

Immunizations and serum antibody ELISA

Five to 10 mice/group were immunized unless otherwise indicated. A single s.c. immunization was administered over both flanks on Day 0, immediately following collection of pre-bleed sera. Unless indicated otherwise, immunizations consisted of 10 μg NP-KLH in 200 μl sterile, LPS-free PBS or NP-KLH mixed with 4 μg α-GC. Mice were then bled at Days 7 and 14 postimmunization and sera obtained. On Day 21, mice were bled and then boosted s.c. with 10 μg NP-KLH in PBS and bled on Days 31 and 35 unless otherwise indicated. At the end of the experimental period, mice were euthanized. Retro-orbital eye bleed, serum collection, and endpoint anti-NP IgG1 titers in serum were measured as described previously [20].

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated at 4°C or room temperature at a density of 107 cells/ml in FACS buffer (PBS+2% BSA) with 2.4G2 mAb at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Fluorochrome-conjugated mAb were added at a 1:100 to a 1:500 dilution as appropriate or with Allophycocyanin-conjugated CD1d tetramer and Pro5H2-Kb OVA257–264 pentamer at a 1:250 dilution of the stock. Cell-surface markers were analyzed with the following specific antibodies: anti-TCR-β (clone H57-597), anti-CD3ϵ (clone 145-2C11), anti-CD1d (clone 7D4), anti-MHC-II (clone AF6-120.1), anti-GR.1 (clone RB6-8C5), anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), anti-CD11c (clone HL3), anti-CD62L (clone MEL-14), anti-CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2), anti-CD19 (clone 1D3), NK1.1 (clone PK136), anti-CD45.1 (clone A20), and anti-CD45.2 (clone 104e). After 1 h, unbound mAb was removed by washing and centrifugation. Cells were fixed with 1% w/v paraformaldehyde and analyzed using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Dead cells (7-AAD+) were excluded from the analysis. Data were processed with WinMDI software (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA).

CFSE labeling of T cells

CD8+ T cells were prepared from RAG2/OT-1 mouse LNs and spleens by depleting CD4+, CD19+, CD11b+, CD11c+, and CD62L+ cells. Briefly, after Fc-block, the depleting cell population was first labeled with biotinylated mAb and then depleted by streptavidin-microbeads using AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec). The depleted cell fraction (95%) consisted of CD8+ T cells. These enriched CD8+ T cells (107 cells/ml) were resuspended further in prewarmed HBSS and labeled with 5 μM CFSE by incubating for 10 min at 37°C, followed by extensive washing in cold HBSS (5% BSA). After final wash, CFSE-labeled cells were resuspended in sterile LPS-free PBS before adoptive transfer.

Adoptive transfer and in vivo proliferation of OT-1 T cells

The RAG2/OT-1(CD8+CD45.2+CFSE+) T cells (106 cells/mouse) were injected i.v. into DT-treated or untreated CD11c-DTR mice, 100% DTR, and CD1d−/−:DTR chimera recipients. After 24 h, OVA (100 μg/mouse) or LPS-free PBS (200 μl/mouse), in the presence or absence of α-GC (4 μg/mouse), was administered by the i.p. route. Adoptively transferred transgenic T cells were identified with flow analysis. OVA-specific T cell proliferation was assessed in spleen and LN cell suspensions, 72 h later, by monitoring the decrease in CFSE fluorescence intensity.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± sd. Statistical differences were determined using a two-tailed paired t test from Graph-Pad Prism. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

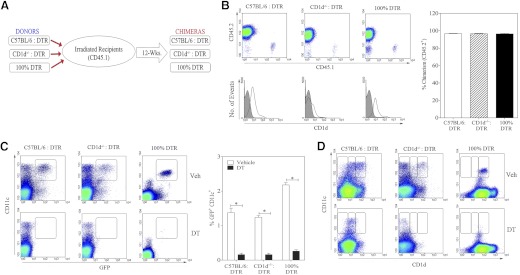

Bone marrow chimera generation and characterization

We generated three distinct bone marrow chimeras, as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our recently published results [20, 21], all three types of chimera (C57BL/6:DTR; CD1d−/−:DTR; and 100% DTR) were reconstituted, such that >94% of immune cells in the periphery were donor-derived CD45.2+ cells (Fig. 1B). Total splenocytes were examined by flow cytometry. Total CD1d expression was lower in the CD1d−/−:DTR chimeras than in the C57BL/6:DTR and the 100% DTR chimeras, as only 50% of the donor cells expressed CD1d (Fig. 1B, lower panels). We also examined CD1d expression on CD11c− cells and CD11c+ cells (Fig. 1C). We observed that CD1d expression on CD11c+ DCs had a pattern distinct from that of total splenocytes or CD11c− splenocytes, in that the DTR-transgenic cells had a higher average expression of CD1d than nontransgenic cells. The reason for this is unclear but did not affect the experiment, as these cells were the target of the DT treatment.

Figure 1. Bone marrow chimera generation and characterization.

(A) Outline of the strategy used for generating bone marrow chimeras. Recipient mice (CD45.1+) were lethally irradiated and engrafted with a 50/50 mixture or 100% of bone marrow cells from donor mice (CD45.2+). (B) After 12 weeks, splenocytes were obtained from chimeric mice and analyzed by flow cytometry for reconstitution of CD45.2+ donor cells. Density plots show reconstitution of CD45.2+ cells in all three chimeras (upper panel). Histogram overlay (lower panel) shows staining of cell-surface CD1d on total splenocytes (black line) versus background staining with an isotype control mAb (gray shaded). The graph on the right shows consistent engraftment of CD45.2+ donor cells for five mice/group. (C and D) Density plots show the effect of vehicle (upper panels) and DT (lower panels) on the frequency of (C) CD11c+GFP+ and (D) CD11c+CD1d+ DCs in splenocytes. The graph on the right shows the effect of DT on frequency of splenic CD11c+/GFP+ DTR-transgenic cells for each chimera (mean±sem for five mice/group). Statistically significant differences among experimental groups are indicated by asterisks.

We therefore tested the effect of DT treatment in all three types of chimeras (Fig. 1C and D). The DTR-transgenic, donor-derived DCs (GFP+) were depleted within 24 h following administration of a single dose of DT. In contrast, nontransgenic DCs were not depleted by DT treatment. Consequently, when the C57BL/6:DTR and the CD1d−/−:DTR chimeras were treated with DT, the remaining DCs were CD1d+ in the former group and CD1d− in the latter group. The depletion of DTR-derived GFP+CD11c+ DCs persisted for at least 7 days after DT treatment. This experimental system provided us with a tool to directly compare the functions of CD1d+ and CD1d− DCs in an otherwise CD1d+ environment.

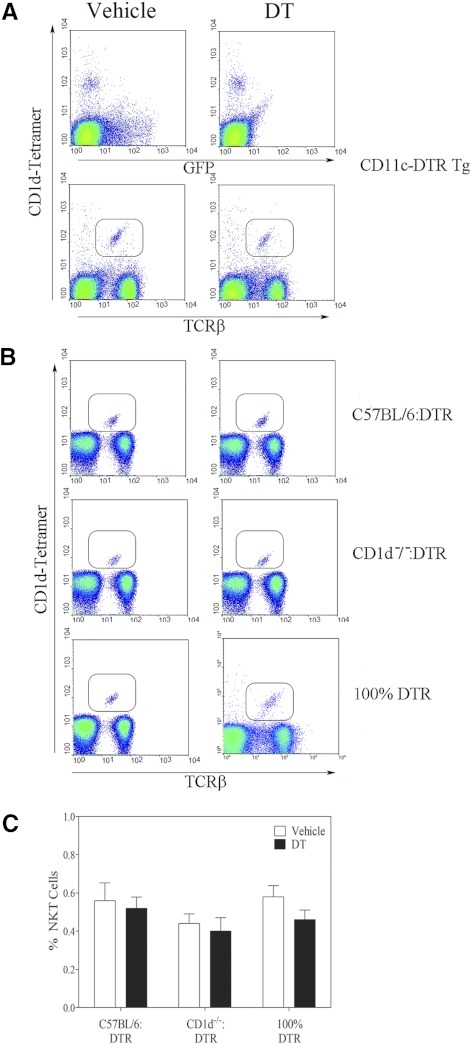

We analyzed the donor CD11c-DTR-transgenic mice before and after DT treatment (Fig. 2). The GFP+ (CD11c+ DCs) cells were depleted following DT treatment, whereas the CD1d-tetramer+ NKT cells were not affected (Fig. 2A). This was expected, as tetramer-binding cells did not express the DTR/GFP transgene. Similarly, in all three chimeras, the percentage of CD1d-tetramer+ NKT cells was the same before and after DT exposure (Fig. 2B). Further, the CD11c-DTR donors and the reconstituted chimeras had normal frequencies of B cells, T cells, and granulocytes (data not shown). This confirms that the chimeras provided a tool to delineate the role of CD1d+ versus CD1d− DCs, while keeping CD1d expression intact on other APCs, such as macrophages and B cells and without deleterious effects on the NKT population.

Figure 2. DT treatment does not deplete NKT cells.

Splenocytes were obtained from vehicle or DT-treated (A) donor DTR mice and (B) reconstituted chimeras and then assessed by flow cytometry. (A) Dot-plots in the upper row show CD1d tetramer binding versus expression of the GFP/DTR transgene. The lower row shows expression of TCR-β versus binding of the CD1d tetramer. (B) Expression of TCR-β versus binding of the CD1d tetramer for the chimeras used in this study. Left and right columns depict samples from vehicle and DT-treated mice, respectively. (C) Graph indicates the effect of DT treatment on NKT frequency in the chimeras for three mice/group.

CD1d expression by DCs is dispensable for NKT-enhanced, antigen-specific antibody production

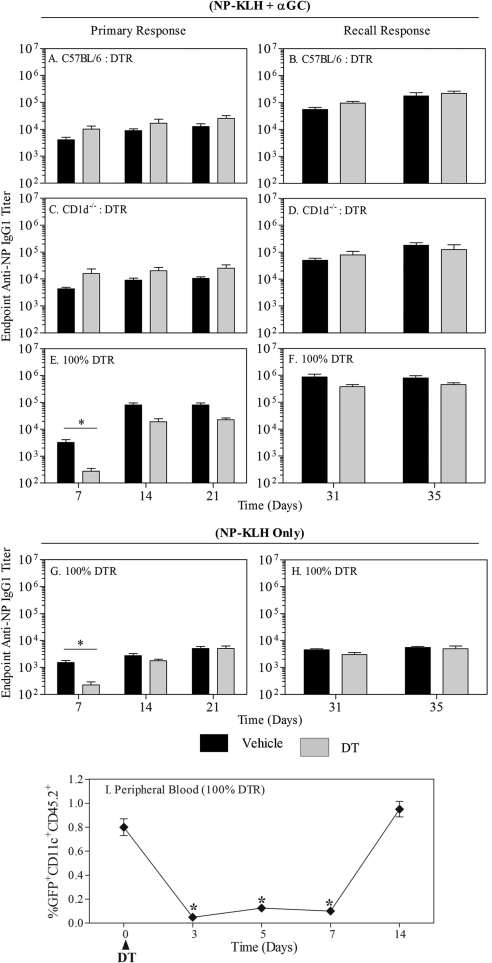

Following DT or vehicle treatment, C57BL/6:DTR, CD1d−/−:DTR, and 100% DTR chimera were immunized with NP-KLH plus α-GC. Depletion of CD1d-expressing DCs (C57BL/6 DCs were intact) did not impair the primary (Fig. 3A) or recall IgG1 responses (Fig. 3B) in the C57BL/6:DTR chimera group. Similarly, in the CD1d−/−:DTR chimeras, where there was a total absence of CD1d+ DCs after DT injection (CD1d− DCs were intact), the primary (Fig. 3C) or recall IgG1 responses (Fig. 3D) were not affected. In the 100% DTR chimeras, the primary IgG1 response was transiently but significantly impaired in the DT-treated group (complete absence of DCs), as compared with the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3E), whereas the recall IgG1 response was not affected (Fig. 3F). Consistent with several previous reports, administration of NP-KLH led to substantially lower IgG1 titers than observed for NP-KLH plus α-GC (Fig. 3G and H) [10–12]. Analysis of CD11c+ cells in peripheral blood revealed that they were depleted at least 7 days after DT administration but had recovered by Day 14. The temporal pattern of DC depletion was therefore similar to that of the antibody response (Fig. 3I). Also, consistent with previous work, IgG1 titers were dominant in the overall IgG response, and changes in titer were not compensated by changes in other subclasses, including Th1-driven IgG2c (data not shown). These results indicate that CD1d expression by DCs was not required to generate a primary or recall antibody response. However, a complete ablation of DCs delayed the primary antibody response.

Figure 3. CD1d expression by DCs is dispensable for NKT-enhanced, specific antibody production.

All three chimeras (C57BL/6:DTR, CD1d−/−:DTR, 100% DTR) were divided in two groups: receiving vehicle (black bars; n=9) or DT (gray bars; n=10) and immunized with NP-KLH plus α-GC, as described in Materials and Methods. Anti-NP IgG1 endpoint titers were measured by ELISA, as described previously [10, 11]. Data show endpoint titers ± sd. (A, C, and E) Graphs show primary antibody responses measured at 7, 14, and 21 days after immunization. (B, D, and F) Graphs show recall responses measured 31 and 35 days after immunization. (G and H) Graphs show response to NP-KLH immunization only in each of the 100% DTR chimera. Similar results were obtained in the mixed chimeras (not depicted). (I) Graph shows the number of CD11c+/GFP+ cells detectable in the peripheral blood of mice used in this experiment. Data show mean ± sem for four mice/group. Asterisks indicate significant differences in cell frequency as compared to pre-treatment (day 0).

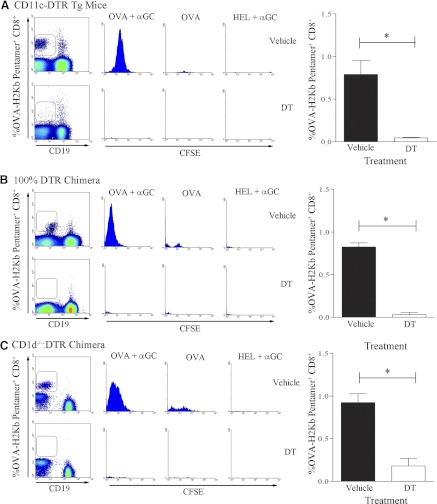

CD1d expression by DCs is required for antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses

Transgenic CD11c+-DTR mice were treated with vehicle or DT, as described in Materials and Methods. These mice then received CFSE-labeled CD8+ OT-1 cells by adoptive transfer and were then immunized with OVA plus α-GC, OVA, or HEL. Expanded OVA-peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were then detected using the OVA-H2-Kb pentamer. As expected, in the vehicle-treated group, there were a significantly higher number of CD8+ T cells detected in mice that received OVA plus α-GC than in those receiving OVA alone (Fig. 4A, upper panels). Furthermore, the heterologous control antigen HEL did not induce OVA-specific CD8+ T cell expansion. In the group of mice that received DT, minimal expansion of OVA-specific CD8+ T cell was observed (Fig. 4A, lower panels). To further investigate the effect of a complete absence of CD1d+ DCs, we transferred the CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells into the 100% DTR chimeras (Fig. 4B). In this experiment, DT treatment also prevented proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. The CD1d−/−:DTR chimeras were then treated with vehicle or DT before repeating the experiment (Fig. 4C). It was observed that DT treatment led to substantially less CD8+ T cell expansion than in the control group. This demonstrates that CD1d expression by DCs is required for α-GC-enhanced CD8+ T cell expansion.

Figure 4. CD1d expression by DCs is required for NKT-enhanced CD8+ T cell expansion.

Twenty-four hours after vehicle or DT treatment, CFSE-labeled CD8+OT-1 cells were transferred into (A) CD11c-DTR mice or (B) 100% DTR chimeras. After a further 24 h, recipient mice were immunized i.p. with OVA plus α-GC (n=3), OVA alone (n=3), or HEL plus α-GC (n=3). After 72 h, splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. After initial gating on FSC+CD8+ cells, OVA-H2-Kb Pentamer+CD19− cells (density plots) were analyzed for CFSE dilution (histograms). OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response in (A) CD11c-DTR mice, (B) 100% DTR chimeras, or (C) CD1d−/−:DTR chimeras treated with vehicle (upper panels) and DT (lower panels) is shown as CFSE dilution after 72 h. The bar graphs on the right summarize the results from two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between experimental groups.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that CD1d expression by DCs is dispensable for NKT-enhanced primary and recall antibody responses, but in the temporary absence of all DCs, primary antibody responses are delayed. In contrast, in the absence of CD1d-expressing DCs, expansion of CD8+ T cells was completely abrogated. These results unexpectedly showed that CD1d expression by DCs did not govern antibody responses. This further solidifies the notion that the type of APC that presents a CD1d-binding glycolipid influences the type of adaptive-immune response that ensues [36].

Three different laboratories reported that B cell help by NKT cells depended on CD1d expression by B cells [14, 17–19]. Our laboratory used adoptive transfer procedures to establish that CD1d− B cells in a CD1d+ environment had impaired α-GC-enhanced antibody responses [13]. Leadbetter and colleagues [18] reported that CD1d+ B cells were required for producing NP-hapten-specific antibodies following immunization with NP-haptenylated α-GC. Barral and colleagues [17] reported that BCR capture of particle-associated, T-dependent, antigen-incorporating α-GC led to enhanced NKT-dependent B cell help. However, Tonti and colleagues [19] generated mixed bone marrow chimeras with CD1d− B cells and observed that α-GC could still enhance specific antibody responses. Contrary to this notion, we recently observed that NKT cell-derived IL-4 and IFN-γ could shape IgG2b and IgG2c responses but were largely dispensable for the overall effect on IgG1 production [20]. In another study, NKT cells deficient in CD40L could not provide B cell help when Th cells lacked CD40L. However, NKT cells deficient in CD40L did provide help for antibody production in cooperation with CD40L+ Th cells [21]. Consequently, there appears to be room for cognate and noncognate B cell help by NKT cells. The degree to which cognate versus noncognate help occurs may depend on the antigen, the dose, and route of immunization and the numbers of B cells and Th cells involved in the response. Our results shed additional light on questions surrounding when and where NKT cells interact with CD1d+ cells to affect a humoral immune response. As CD1d expression by DCs was not required for antibody production, it seems very likely that NKT cell interaction with DCs at the immunization site is not a required part of the process. This is consistent with our results indicating a need for CD1d expression by B cells [13] and placing the interaction between NKT cells and CD1d+ APCs in the secondary lymphoid organs. Indeed, results by Barral and coworkers [17] did show NKT foci in secondary lymphoid organs following immunization. In a recent publication, direct interaction of NKT cells and B cells was visualized by intravital microscopy [37], confirming interaction in secondary lymphoid organs.

However, none of the B cell-oriented studies has precluded nor directly addressed a role for DC CD1d in the initiation of an antibody response. To address the contribution of CD1d on DCs in antibody responses, we reconstituted three types of bone marrow chimeras. Either 50% of DCs were CD1d+ (C57BL/6:DTR) or 50% of DCs were CD1d− (CD1d−/−:DTR). In a third chimera, all DCs were CD1d+ but DTR-transgenic (100% DTR) and depleted by DT treatment. This valuable tool allowed us to deplete DTR DCs, such that CD1d+ and CD1d− DCs could be compared in the context of an otherwise CD1d+ environment. In the present study, it was observed that CD1d expression by DCs was not essential to induce a NKT-mediated primary B cell response. However, the antibody response was significantly but transiently impaired in the total absence of DCs in an otherwise CD1d+ environment, indicating that DCs were required for generating an antibody response to the antigen. This effect was observed 7 days after the initial immunization, and the eventual recovery of the antibody response by 14 days postimmunization was consistent with recovery of the transiently ablated DC population. This suggests that the antigen and α-GC adjuvant persist for sufficiently long for capture, processing, and presentation by the recovering CD1d+ DCs.

It has been observed several times that the coadministration of soluble antigen and α-GC leads to enhanced activation and/or function of CD4+ T cells [12, 24, 26]. After the submission of this manuscript, it was reported that a subset of NKT cells can adopt a T follicular helper phenotype following antigen and α-GC administration [37, 38]. This suggests the intriguing possibility that DC CD1d could differentially affect CD4 T cell responses that govern B cell and CTL responses, respectively. Further research will be required to explore this important link between different arms of the adaptive-immune response.

It is well established that the CD1d ligand α-GC, when coadministered with a T-dependent antigen, is able to boost antigen-specific CTL responses and antibody production, increasing the potential for tumor rejection [25–30, 39] and toxin [20] or virus [40] neutralization, respectively. Investigations into CD8+ T cell induction have essentially “drawn a line” from DC presentation of CD1d/α-GC to NKT-dependent IFN-γ production, CTL expansion, and tumor rejection [39]. It is therefore reasonably clear that DC CD1d is important for maximizing the cellular arm of adaptive-immune responses. Our data clearly confirmed that the presence of CD1d+ DCs was essential for antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion. We also advanced on these findings by generating a system in which CD1d− DCs could be examined in a CD1d+ environment without the need for isolation and adoptive transfer of antigen/α-GC-pulsed DCs. We anticipate that the mixed chimera approach described herein will be of value to those studying NKT-enhanced adaptive-immune responses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Gates Foundation Grand Challenge research grant (RG-21 019-N) to S.K.J. and NIH grant AI087793 to M.L.L. The authors thank the NIAID tetramer facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA) for supplying the CD1d tetramers.

Footnotes

- 7-AAD

- 7-aminoactinomycin D

- α-GC

- α-galactosylceramide

- CD40L/CD62L

- CD40/CD62 ligand

- DT

- diphtheria toxin

- HEL

- hen egg lysozyme

- KLH

- keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- NIAID

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- NP

- nitrophenol

- OUHSC

- The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- RAG2

- recombination-activating gene 2

AUTHORSHIP

S.K.J. designed and directed the project, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. G.A.L., T.S.D., A.M.J, and S.K. performed experiments and analyzed data. M.L.L. designed and directed the project, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Taniguchi M., Harada M., Kojo S., Nakayama T., Wakao H. (2003) The regulatory role of Vα14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 483–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kronenberg M. (2005) Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 877–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seino K., Taniguchi M. (2005) Functionally distinct NKT cell subsets and subtypes. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1623–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bendelac A., Savage P. B., Teyton L. (2007) The biology of NKT cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 297–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Godfrey D. I., Stankovic S., Baxter A. G. (2010) Raising the NKT cell family. Nat. Immunol. 11, 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawano T., Cui J., Koezuka Y., Toura I., Kaneko Y., Motoki K., Ueno H., Nakagawa R., Sato H., Kondo E., Koseki H., Taniguchi M. (1997) CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of vα14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science 278, 1626–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burdin N., Brossay L., Kronenberg M. (1999) Immunization with α-galactosylceramide polarizes CD1-reactive NKT cells towards Th2 cytokine synthesis. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 2014–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan B. A., Nagarajan N. A., Wingender G., Wang J., Scott I., Tsuji M., Franck R. W., Porcelli S. A., Zajonc D. M., Kronenberg M. (2010) Mechanisms for glycolipid antigen-driven cytokine polarization by Vα14i NKT cells. J. Immunol. 184, 141–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galli G., Pittoni P., Tonti E., Malzone C., Uematsu Y., Tortoli M., Maione D., Volpini G., Finco O., Nuti S., Tavarini S., Dellabona P., Rappuoli R., Casorati G., Abrignani S. (2007) Invariant NKT cells sustain specific B cell responses and memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3984–3989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Devera T. S., Shah H. B., Lang G. A., Lang M. L. (2008) Glycolipid-activated NKT cells support the induction of persistent plasma cell responses and antibody titers. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1001–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lang G. A., Johnson A. M., Devera T. S., Joshi S. K., Lang M. L. (2011) Reduction of CD1d expression in vivo minimally affects NKT-enhanced antibody production but boosts B-cell memory. Int. Immunol. 4, 251–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lang G. A., Exley M. A., Lang M. L. (2006) The CD1d-binding glycolipid α-galactosylceramide enhances humoral immunity to T-dependent and T-independent antigen in a CD1d-dependent manner. Immunology 119, 116–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang G. A., Devera T. S., Lang M. L. (2008) Requirement for CD1d expression by B cells to stimulate NKT cell-enhanced antibody production. Blood 111, 2158–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang M. L. (2009) How do natural killer T cells help B cells? Expert Rev. Vaccines 8, 1109–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Devera T. S., Aye L. M., Lang G. A., Joshi S. K., Ballard J. D., Lang M. L. (2010) CD1d-dependent B-cell help by NK-like T cells leads to enhanced and sustained production of Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin-neutralizing antibodies. Infect. Immun. 78, 1610–1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lang G. A., Illarionov P. A., Glatman-Freedman A., Besra G. S., Lang M. L. (2005) BCR targeting of biotin-{α}-galactosylceramide leads to enhanced presentation on CD1d and requires transport of BCR to CD1d-containing endocytic compartments. Int. Immunol. 17, 899–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barral P., Eckl-Dorna J., Harwood N. E., De Santo C., Salio M., Illarionov P., Besra G. S., Cerundolo V., Batista F. D. (2008) B cell receptor-mediated uptake of CD1d-restricted antigen augments antibody responses by recruiting invariant NKT cell help in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8345–8350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leadbetter E. A., Brigl M., Illarionov P., Cohen N., Luteran M. C., Pillai S., Besra G. S., Brenner M. B. (2008) NKT cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8339–8344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tonti E., Galli G., Malzone C., Abrignani S., Casorati G., Dellabona P. (2009) NKT-cell help to B lymphocytes can occur independently of cognate interaction. Blood 113, 370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Devera T. S., Joshi S. K., Aye L. M., Lang G. A., Ballard J. D., Lang M. L. (2011) Regulation of anthrax toxin-specific antibody titers by natural killer T cell-derived IL-4 and IFNγ. PLoS One 6, e23817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shah H. B., Joshi S. K., Lang M. L. (2011) CD40L-null NKT cells provide B cell help for specific antibody responses. Vaccine 29, 9132–9136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Austyn J. M. (2000) Antigen-presenting cells: experimental and clinical studies of dendritic cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162, 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guermonprez P., Valladeau J., Zitvogel L., Clotilde Thery C., Amigorena S. (2002) Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 621–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fujii S., Shimizu K., Kronenberg M., Steinman R. M. (2002) Prolonged IFN-γ-producing NKT response induced with α-galactosylceramide-loaded DCs. Nat. Immunol. 9, 867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujii S., Shimizu K., Smith C., Bonifaz L., Steinman R. M. (2003) Activation of natural killer T cells by α-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J. Exp. Med. 198, 267–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hermans I. F., Silk J. D., Gileadi U., Salio M., Mathew B., Ritter G., Schmidt R. R., Harris A. L., Old L., Cerundolo V. (2003) NKT cells enhance CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 171, 5140–5147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Münz C., Steinman R. M., Fujii S. (2005) Dendritic cell maturation by innate lymphocytes: coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. J. Exp. Med. 202, 203–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujii S., Shimizu K., Hemmi H., Fukui M., Bonito A. J., Chen G., Franck R. W., Tsuji M., Steinman R. M. (2006) Glycolipid α-C-galactosylceramide is a distinct inducer of dendritic cell function during innate and adaptive immune responses of mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11252–11257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimizu K., Kurosawa Y., Taniguchi M., Steinman R. M., Fujii S. (2007) Cross-presentation of glycolipid from tumor cells loaded with α-galactosylceramide leads to potent and long-lived T cell-mediated immunity via dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2641–2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujii S., Shimizu K., Hemmi H., Steinman R. M. (2007) Innate Vα14(+) natural killer T cells mature dendritic cells, leading to strong adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 220, 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brigl M., Tatituri R. V., Watts G. F., Bhowruth V., Leadbetter E. A., Barton N., Cohen N. R., Hsu F. F., Besra G. S., Brenner M. B. (2011) Innate and cytokine-driven signals, rather than microbial antigens, dominate in natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1163–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mattner J., Debord K. L., Ismail N., Goff R. D., Cantu C., III, Zhou D., Saint-Mezard P., Wang V., Gao Y., Yin N., Hoebe K., Schneewind O., Walker D., Beutler B., Teyton L., Savage P. B., Bendelac A. (2005) Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature 434, 525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pei B., Speak A. O., Shepherd D., Butters T., Cerundolo V., Platt F. M., Kronenberg M. (2011) Diverse endogenous antigens for mouse NKT cells: self-antigens that are not glycosphingolipids. J. Immunol. 186, 1348–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jung S., Unutmaz D., Wong P., Sano G., De los Santos K., Sparwasser T., Wu S., Vuthoori S., Ko K., Zavala F., Pamer E. G., Littman D. R., Lang R. A. (2002) In vivo depletion of CD11c(+) dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8(+) T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity 17, 211–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shinkai Y., Rathburn G., Lam K. P., Oltz E. M., Stewart V., Mendelsohn M., Charron J., Datta M., Young F., Stall A. M., Alt F. W. (1992) RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphcytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell 68, 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bezbradica J. S., Stanic A. K., Matsuki N., Bour-Jordan H., Bluestone J. A., Thomas J. W., Unutmaz D., Van Kaer L., Joyce S. (2005) Distinct roles of dendritic cells and B cells in Va14Ja18 natural T cell activation in vivo. J. Immunol. 174, 4696–4705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang P. P., Barral P., Fitch J., Pratama A., Ma C. S., Kallies A., Hogan J. J., Cerundolo V., Tangye S. G., Bittman R., Nutt S. L., Brink R., Godfrey D. I., Batista F. D., Vinuesa C. G. (2011) Identification of Bcl-6-dependent follicular helper NKT cells that provide cognate help for B cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 13, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. King I. L., Fortier A., Tighe M., Dibble J., Watts G. F., Veerapen N., Haberman A. M., Besra G. S., Mohrs M., Brenner M. B., Leadbetter E. A. (2011) Invariant natural killer T cells direct B cell responses to cognate lipid antigen in an IL-21-dependent manner. Nat. Immunol. 13, 44–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teng M. W., Sharkey J., McLaughlin N., Exley M. A., Smyth M. J. (2009) CD1d-based combination therapy eradicates established tumors in mice. J. Immunol. 183, 1911–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kakimi K., Guidotti L., Koezuka Y., Chisari F. (2000) NKT cell activation inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 192, 921–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]