Abstract

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of spinal cord and optic nerve caused by pathogenic autoantibodies (NMO-IgG) against astrocyte aquaporin-4 (AQP4). We developed a high-throughput screen to identify blockers of NMO-IgG binding to human AQP4 using a human recombinant monoclonal NMO-IgG and transfected Fisher rat thyroid cells stably expressing human M23-AQP4. Screening of ∼60,000 compounds yielded the antiviral arbidol, the flavonoid tamarixetin, and several plant-derived berbamine alkaloids, each of which blocked NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 without affecting AQP4 expression, array assembly, or water permeability. The compounds inhibited NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 in NMO patient sera and blocked NMO-IgG-dependent complement- and cell-mediated cytotoxicity with IC50 down to ∼5 μM. Docking computations identified putative sites of blocker binding at the extracellular surface of AQP4. The blockers did not affect complement-dependent cytotoxicity caused by anti-GD3 antibody binding to ganglioside GD3. The blockers reduced by >80% the severity of NMO lesions in an ex vivo spinal cord slice culture model of NMO and in mice in vivo. Our results provide proof of concept for a small-molecule blocker strategy to reduce NMO pathology. Small-molecule blockers may also be useful for other autoimmune diseases caused by binding of pathogenic autoantibodies to defined targets.—Tradtrantip, L., Zhang, H., Anderson, M. O., Saadoun, S., Phuan, P.-W., Papadopoulos, M. C., Bennett, J. L., Verkman, A. S. Small-molecule inhibitors of NMO-IgG binding to aquaporin-4 reduce astrocyte cytotoxicity in neuromyelitis optica.

Keywords: water channel, Devic's disease, drug discovery, autoantibody

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) with distinct clinical and histological features from multiple sclerosis, including a propensity for lesions in spinal cord and optic nerve over brain (1). A defining feature of NMO is the presence of serum autoantibodies, NMO immunoglobulin G (NMO-IgG), against aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a plasma membrane water channel expressed in astrocytes throughout the CNS (2–4). Phenotype analysis of AQP4-knockout mice has revealed the involvement of AQP4 in brain and spinal cord water balance (5, 6), neuroexcitatory phenomena (7, 8), astrocyte migration and glial scarring (9, 10), and neuroinflammation (11). Current NMO therapy consists of anti-inflammatory agents and maneuvers that reduce circulating NMO-IgG, such as plasmapheresis and B-cell-depleting monoclonal antibody therapy (12, 13).

NMO-IgG is believed to be pathogenic in NMO. The administration of human NMO-IgG increases the severity of inflammatory lesions in rats with preexisting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (14–16). Injection of NMO-IgG with human complement into brain parenchyma of naive mice produces characteristic NMO lesions with perivascular inflammation and complement deposition, demyelination, and loss of AQP4 and glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity (17, 18). Similar lesions are produced by exposure of ex vivo spinal cord slice cultures to NMO-IgG and complement (19). It is thought that NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 on the surface of astrocytes causes complement- and perhaps cell-mediated astrocyte damage, which initiates a cascade of proinflammatory events, including cytokine release, microglial activation, and leukocyte accumulation, resulting in demyelination and clinical disease (20–22).

Here, we investigated the possibility of blocking NMO-IgG binding to cell surface AQP4 by small, drug-like molecules as a therapeutic strategy for NMO. The rationale for this approach is to target the initiating pathogenic event in NMO rather than downstream inflammatory events. This rationale is supported by our recent report that an engineered, nonpathogenic monoclonal anti-AQP4 antibody (“aquaporumab”), which blocks NMO-IgG binding to AQP4, reduces NMO pathology in mouse models (23). Here, we developed a cell-based high-throughput screen to identify small-molecule blockers of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4. Screening of unbiased collections of synthetic small molecules, natural products, and drugs yielded several chemical classes of blockers, including an antiviral drug and several natural products, which reduced NMO-IgG dependent cytotoxicity in cell cultures and NMO pathology in mouse models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and antibodies

Fisher rat thyroid (FRT) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing M23-AQP4 were generated by stable transfection with plasmid encoding human M23-AQP4, as described previously (24). FRT cells were cultured in F-12 modified Coon's medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. CHO cells were cultured in F-12 Ham's nutrient mix medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Geneticin (200 μg/ml) was used as selection marker. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air. SK-MEL-28 human skin melanoma cells were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Recombinant monoclonal NMO antibodies (NMO-rAbs) were generated from clonally expanded plasma blasts from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with NMO and purified as described previously (14). NMO serum was obtained from NMO-IgG-seropositive individuals who met the revised diagnostic criteria for clinical disease (25). Non-NMO human serum was used as control. For some studies, IgG was purified from NMO or control serum and was concentrated using a Melon Gel IgG Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Compounds

The compound collections used for screening included ∼50,000 synthetic small molecules (Asinex, Winston-Salem, NC, USA), ∼7500 purified natural compounds (Analyticon, Postdam, Germany; Timtec, Newark, NJ, USA; and Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), and ∼4000 approved drugs and investigational compounds (Microsource, Gaylordsville, CT, USA; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA; and BioFocus, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Compounds were stored in 96-well plates at 2.5 mM in DMSO. Compound analogs were purchased from Asinex and ChemDiv (San Diego, CA, USA). Berbamine dihydrochloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; cycleanine, cepharanthin, fangchinoline, and dauricine from Quality Phytochemicals (Edison, NJ, USA); laudanosine from Ryan Scientific (Mt. Pleasant, SC, USA); arbidol from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); tamarixetin from Indofine Chemical Co. (Hillsborough, NJ, USA); quercetin from Sigma-Aldrich; and isorhamnetin from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA).

High-throughput screening

Screening was performed using an integrated apparatus (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) consisting of a CO2 incubator, plate washer (Elx405; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA), liquid-handling station (Biomek FX; Beckman Coulter), and plate readers (FluoStar Optima; BMG Lab Technologies, Chicago, IL, USA). FRT cells were plated in black 96-well plates with clear plastic bottom (Costar; Corning, Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 20,000 cells/well. Eighty wells contained test compounds, and the first and last columns of each plate were used for negative (FRT-M23, no test compound) and positive (FRT-null, no test compound) controls. For screening, after overnight growth to reach confluence, cells were washed twice with PBS, leaving 40 μl PBS. Test compounds were added (0.5 μl of 2.5 mM DMSO solution) to each well at 25 μM final concentration. A premixed solution (10 μl) of NMO-IgG (recombinant monoclonal antibody rAb-53, 1 μg/ml; refs. 14, 26) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-human IgG secondary antibody (1:500 dilution; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was then added and incubated with cells for 1 h. After washing each well 3 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, 50 μl Amplex Red substrate (100 μM, Sigma) and 2 mM H2O2 were added for measurement of HRP activity. Fluorescence was measured after 10 min (excitation 540 nm, emission 590 nm). Percentage inhibition was computed as (negative control − compound)/(negative control − positive control) × 100.

NMO-IgG binding

Cells were grown on glass coverslips for 24 h. After blocking with 1% BSA in PBS, cells were incubated with compound or DMSO for 30 min, followed by a 1:100 dilution of NMO or control serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa-Fluor 555 goat anti-human IgG secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen). In some experiments, binding was measured of Cy3-conjugated rAb-53 (at 20 μg/ml). For AQP4 immunostaining, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton-X. Rabbit anti-AQP4 antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added, followed by Alexa Fluor-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen) (24).

Complement- and NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity

For assay of complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), CHO cells expressing human M23-AQP4 were incubated for 30 min with test compound or vehicle control, then for 90 min at 37°C with NMO-rAb or control rAb (2.5 μg/ml), or with NMO or control serum (1:100 dilution) together with 5% human complement. CDC of an unrelated antibody and antigen was assayed by incubation of SK-MEL-28 cells for 1.5 h at 37°C with 8 μg/ml antiganglioside GD3-IgG (R24, an IgG3 mouse mAb, GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) and 5% human complement. Calcein-AM and ethidium-homodimer (Invitrogen) were added to stain live cells green and dead cells red. For assay of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), NK-92 cells expressing CD16 (Conkwest, San Diego, CA, USA) were used as the effector cells. AQP4-expressing CHO cells were incubated for 30 min with test compound (or vehicle control), then for 3 h at 37°C with NMO-rAb or control rAb (5 μg/ml) and effector cells at an effector:target cell ratio of 30:1, followed by live-dead cell staining.

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM)

TIRFM was done using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000E microscope equipped with through-objective TIRF attachment and ×100 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.49; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously (27). CHO cells expressing M23-AQP4 were incubated for 60 min with test compound or DMSO vehicle control, then fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, and AQP4 was stained with rAb-53 and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-human secondary antibody as described above. TIRFM images of Alexa fluorescence were acquired using a QuantEM 512SC deep-cooled CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA).

Osmotic water permeability

Osmotic water transport across FRT epithelial cell monolayers was measured from the dilution of a cell-impermeant, inert dye (Texas Red-dextran, 10 kDa; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA; ref. 28). Nontransfected or AQP4-expressing FRT cells were grown on 12-mm-diameter Transwell polycarbonate porous inserts (0.4 μm pore size; Costar,) until a tight monolayer formed (electrical resistance 2–5 kΩ·cm2). The basal cell surface was bathed in 1 ml isosmolar PBS. The apical surface was bathed in 200 μl of hyperosmolar PBS (PBS+300 mM d-mannitol) containing 0.25 mg/ml Texas Red-dextran. Test compounds were added to both the apical and basal bathing solutions. Samples (5 μl) of dye-containing apical fluid were collected at specified times and diluted in 2 ml PBS, and fluorescence was measured at 615 nm. Transepithelial osmotic water permeability coefficient (Pf, cm/s) was computed as described previously (28).

Ex vivo spinal cord slice model of NMO

Wild-type and AQP4-null mice in a CD1 genetic background were used, as generated and characterized previously (29). Transverse slices of cervical spinal cord of thickness 300 μm were cut from postnatal day 7 pups using a vibratome and placed in ice-cold Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; pH 7.2), as described previously (19). Slices were placed on transparent membrane inserts (Millicell-CM, 0.4 μm pores, 30 mm diameter; Millipore) in 6-well plates containing 1 ml culture medium, with a thin film of culture medium covering the slices. Slices were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 7 d in 50% MEM, 25% HBSS, 25% horse serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0.65% glucose, and 25 mM HEPES. On d 7, NMO-rAb or control-rAb (10 μg/ml) and human complement (5%) were added to the culture medium on both sides of the slices, without or with blocker. Slices were cultured for an additional 24 h and were immunostained for AQP4 and GFAP. Sections were scored as follows: 0, intact slice with normal GFAP and AQP4 staining; 1, mild astrocyte swelling and/or reduced AQP4 staining; 2, at least one lesion with loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining; 3, multiple lesions affecting >30% of slice area; 4, lesions affecting >80% of slice area.

In vivo mouse brain injection model of NMO

Protocols were approved by the British Home Office and the University of California–San Francisco Committee on Animal Research. Age and sex-matched adult mice (30–35 g) were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (125 mg/kg i.p.) and mounted in a stereotactic frame. Mice were injected intracerebrally (1 μl/min) with total IgG (14 μl, 6–38 μg/ml) purified from NMO or control sera plus human complement (10 μl), as described previously (18), without or with blocker (2 μg). Mice were killed at 24 h after injection, and brains were fixed in formalin, processed into paraffin, and sectioned coronally at 1.6 mm from the frontal poles. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Luxol Fast Blue (for myelin), and AQP4. Micrographs were quantified for loss of AQP4 immunoreactivity and myelin as described previously (17).

Molecular docking computations

Docking was done using 1.8-Å high-resolution crystal structure data for human AQP4 (accession code 3GD8; ref. 30). Each compound was drawn in ChemDraw (Cambridge Software, Cambridge, MA, USA), converted to a SMILES string, transformed to a 3D conformation, and minimized using Pipeline Pilot (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA). The single conformation was passed through Molcharge (OpenEyes, Santa Fe, NM, USA) to apply AM1BCC charges, and then processed by Omega (OpenEyes) to generate multiconformational libraries. The AQP4 protein was prepared for docking using the Fred-Receptor (OpenEyes) utility. Initial docking was done to the entire protein, which showed compound docking to the cavity on the extracellular surface. Subsequently, the receptor site was constructed using a 12-Å cubic box around the cavity on the extracellular surface for docking computations using Fred 2.2.5 (OpenEyes). Fred was configured to employ consensus scoring, using two scoring functions that best distinguished active vs. inactive compounds: OEChemScore and ZapBind. Docking was performed free of pharmacophore restraint. Each final pose was minimized by molecular dynamics using the MMFF94 force field within the active site. The final protein-ligand complex was visualized using PyMol (Schrödinger, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Identification of small-molecule blockers of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4

Because no precedent has been established for small-molecule blocking of autoantibody-target interaction, our high-throughout screen for identification of blockers of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 was designed to have the greatest likelihood of success. The assay utilized stably transfected FRT cells expressing high levels of the M23 isoform of human AQP4. After testing 5 different cell lines, FRT cells were chosen because of their high-level stable plasma membrane expression of AQP4, rapid growth on 96-well plates, resistance to detachment during washing, and low background signal in the screening assay. The M23 isoform of human AQP4 was used because it forms orthogonal arrays of particles (OAPs) and binds NMO-IgG better than the long, M1 isoform of AQP4 (24, 26, 31–33). A recombinant monoclonal NMO-IgG (14, 26) was used for primary screening, reasoning that the likelihood of success would be greatest for identifying small molecules that prevent the binding of a monoclonal antibody against a unique epitope on AQP4. In addition, signal-to-background was substantially better for a purified monoclonal NMO-IgG compared with IgG in NMO serum.

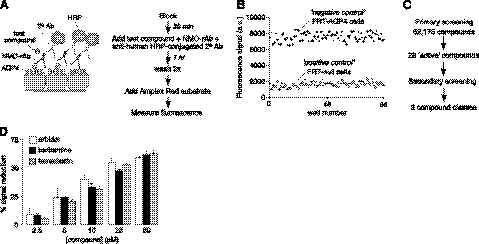

The high-throughput screen was optimized to maximize sensitivity and statistical Z′ factor. As diagrammed in Fig. 1A, following a blocking step, test compounds were added prior to the addition of a solution containing the recombinant monoclonal NMO antibody rAb-53 and HRP-conjugated anti-human secondary antibody. After 1 h incubation, cells were washed thoroughly, and cell-surface-bound HRP was assayed using Amplex Red as a fluorescent substrate. Vehicle alone without test compound was the negative control in 8 wells of each 96-well plate, and nontransfected FRT cells (lacking AQP4) were the positive control. Statistical Z′ factor was >0.6 in 90% of plates in the primary screen, with excellent separation of positive and negative controls (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

High-throughput screen for identification of inhibitors of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4. A) Schematic (left) and flow diagram (right) of the screening assay, which measures the binding of a recombinant monoclonal NMO antibody (NMO-rAb) to AQP4 in live cells, using as readout an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and fluorogenic substrate. B) Separation of positive and negative control data as measured in 96-well plate format. C) Summary of findings from primary screen. D) Concentration-dependent reduction in HRP fluorescence by indicated blockers identified from screening. Values are means ± se (n=4).

Screening of 62,175 synthetic small molecules, natural products, and investigational/approved drugs yielded 28 active compounds that produced >40% reduction of the Amplex Red fluorescence signal (Fig. 1C). Eight of the screened compounds, which fell in 3 different chemical classes, were confirmed as blockers of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4. The blockers included the antiviral arbidol, several related plant-derived berbamine alkaloids, and the quercetin metabolite tamarixetin. Many of the false positives were determined to be HRP enzyme inhibitors (from measurements using purified HRP), while others appeared to block secondary antibody binding to AQP4-bound NMO-IgG. Figure 1D shows concentration-dependent reduction in HRP signal in cells treated with arbidol, berbamine. and tamarixetin; chemical structures are shown in Fig. 2A.

Figure 2.

Small-molecule blockers inhibit NMO-IgG binding to AQP4. A) Chemical structures of blockers. B) Left panel: binding of Cy3-conjugated recombinant monoclonal NMO antibody rAb-53 (red), shown with AQP4 immunofluorescence (green). Cells were incubated with 25 μM blocker for 30 min prior to antibody addition. Background subtracted red-to-green ratios provided. Right panel: Schematic of staining method. Micrographs representative of 4 sets of experiments. C) Immunofluorescence staining by NMO-IgG (total IgG purified from 2 NMO sera) revealed using red fluorescent anti-human secondary antibody. Background subtracted red-to-green ratios provided. Representative of micrographs with sera from 6 different patients with NMO. Values are means ± se (n=3).

Compounds block NMO-IgG binding to AQP4

Blocker action was confirmed by immunofluorescence in AQP4-expressing cell cultures. Binding of a red fluorescent, Cy3-conjugated recombinant NMO antibody was measured with blockers present during the antibody incubation. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized for AQP4 immunostaining using an anti-C-terminal AQP4 antibody and green fluorescent secondary antibody. Figure 2B shows marked reduction in Cy3 fluorescence when cells were incubated with each of the blockers, without significantly reduced AQP4 immunofluorescence. We also investigated whether the blockers identified using a monoclonal NMO-rAb were effective in preventing NMO-IgG binding in sera from patients with NMO, which contain a polyclonal mixture of NMO-IgG autoantibodies that recognize various 3-dimensional epitopes on the extracellular surface of AQP4. Measurements were made using sera from 6 patients with NMO. NMO sera were incubated with the AQP4-expressing cells in the absence or presence of blockers. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, incubated with a red fluorescent anti-human secondary antibody, and immunostained green for AQP4, as above. Representative fluorescence micrographs in Fig. 2C for 2 NMO sera showed marked reduction in NMO-IgG binding in blocker-treated cells. Greatly reduced NMO-IgG binding was found for each of the other 4 NMO sera (not shown).

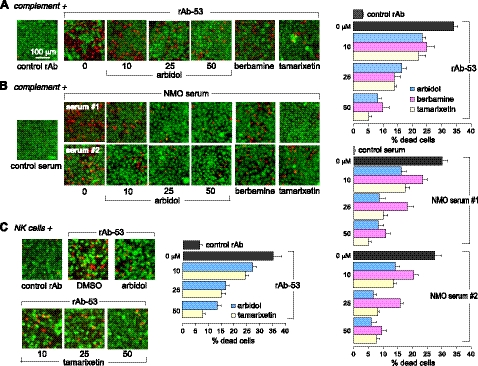

Compounds block antibody-dependent cytotoxicity

CDC was assayed as a measure of biological activity. AQP4-expressing cells were incubated with NMO-IgG for 60 min in the presence of human complement, without or with blocker, and cytotoxicity was assayed using a 2-color staining method in which live cells were stained green and dead cells red. Figure 3A, left panel, shows representative live-dead cell staining, and Fig. 3A, right panel, summarizes percentage of dead cells. Few dead (red) cells were seen using control (non-NMO) rAb (Fig. 3A, leftmost panel), or with NMO-rAb in nontransfected cells (not shown). The blockers reduced cell killing in a concentration-dependent manner in the NMO-IgG/complement-treated AQP4-expressing cells. The compounds also protected against CDC produced in cells treated with complement and sera from patients with NMO, as shown for sera from 2 patients (Fig. 3B). No cell killing was seen with control (non-NMO) serum (Fig. 3B, leftmost panel).

Figure 3.

Small-molecule blockers inhibit NMO-IgG-dependent complement and NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in cell cultures. A) Left panel: live-dead cell staining assay (live cells, green; dead cells, red) of AQP4-expressing CHO cells exposed to rAb-53 and complement in the presence of indicated concentrations of arbidol, or 50 μM berbamine or tamarixetin. Right panel: percentage dead cells. B) Left panel: assay as in A, done with IgG purified from 2 human NMO sera. Right panel: percentage dead cells. C) Left panel: ADCC measured following 3 h incubation of AQP4-expressing CHO cells with NK-cells and rAb-53 in the absence and presence of blocker. Right panel: percentage dead cells. Values are means ± se (n=4–6).

Though CDC is probably the primary disease-producing mechanism in NMO, ADCC may occur as well (34). We investigated whether the blockers are protective in ADCC using a human NK cell line. AQP4-expressing cells were exposed to NK cells and NMO-rAb (without complement) for 3 h without or with test compound prior to live-dead staining. Figure 3C shows few dead cells following exposure to NK cells and control rAb. Arbidol and tamarixetin each protected against NK cell cytotoxicity in a concentration-dependent manner. Berbamine was not studied because it activates NK cells directly.

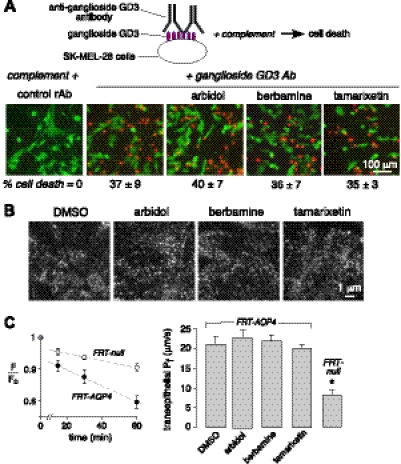

Blocker action involves binding to AQP4

The reduction in NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 by berbamine, arbidol, and tamarixetin could be the result of reduced cell surface AQP4 expression or assembly into OAPs, or compound binding to AQP4 or the Fab region of NMO-IgG. The blocking of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 by multiple NMO patient sera, each containing a polyclonal antibody mixture, suggests binding to the extracellular surface of AQP4. Compound inhibition of the binding of fluorescently labeled NMO-IgG (Fig. 2A), and of NMO-IgG-dependent CDC and ADCC (Fig. 3), argues against downstream and nonselective effects. As further evidence for lack of non-specific blocker effects, we assayed CDC for an unrelated (non-AQP4) antibody-antigen. Figure 4A shows that the blockers at high concentration do not inhibit CDC in SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells produced by binding of anti-ganglioside GD3 antibody to GD3, a prominent glycolipid on human melanoma cells (35). The blockers did not affect cell surface AQP4 expression, as shown in Fig. 2B, C, or OAP assembly, as shown by TIRFM in Fig. 4B. TIRFM showed a similar pattern of punctate AQP4 immunofluorescence following compound incubation, indicating that the blockers do not affect AQP4 cell surface expression or OAP assembly. Finally, berbamine, arbidol, and tamarixetin did not inhibit AQP4 water permeability, as measured by osmotically driven transepithelial water transport across cell monolayers using a fluorescent volume marker (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Small-molecule blocker action involves binding to AQP4. A) Complement-dependent cytotoxicity assay of an unrelated antibody and antigen. Live-dead cell assay of SK-MEL-28 cells exposed to anti-ganglioside GD3 antibody and human complement in the absence and presence of 50 μM blocker (differences not significant). B) TIRFM visualization of OAPs in AQP4-expressing CHO cells without (DMSO) and after 60 min incubation with 50 μM blocker. Representative of 3 sets of studies. C) Left panel: transepithelial osmotic water permeability assayed by dye dilution in nontransfected vs. AQP4-expressing FRT cells. Right panel: summary of deduced Pf from experiments as in A. Blockers were present at 50 μM for 30 min before and during water permeability measurements. Values are means ± se (n=4). *P < 0.001 vs. DMSO control.

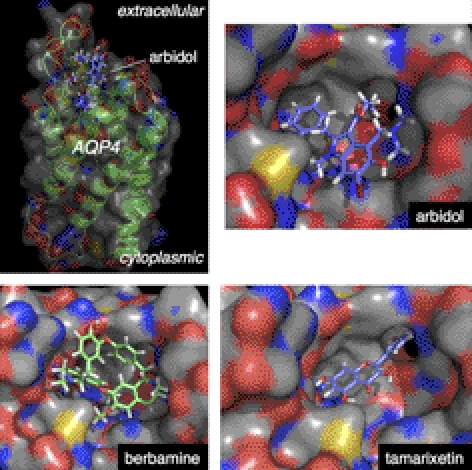

Molecular docking computations identified putative AQP4 binding sites for each blocker class. Docking computations were done using high-resolution X-ray crystal coordinates of human AQP4 (30). For berbamine, arbidol, and tamarixetin, the lowest-energy docked conformations were found at the extracellular region of AQP4 near the central cavity. The lowest-energy docked conformations of arbidol and tamarixetin showed a close complementary fit to the extracellular cavity of AQP4 (Fig. 5). Structural features of the active compounds projected toward a hydrophobic cavity flanked by Leu72, Val68, and Ile57. For tamarixetin, the aryl ring system projects into the cavity, with the methoxy group allowing hydrogen-bond interaction with the Asn58 side-chain amido NH2. For arbidol, the ethyl ester was positioned directly outside the hydrophobic cavity. Blocker binding could inhibit NMO-IgG binding by steric competition or by inducing a conformation change in the extracellular domain of AQP4.

Figure 5.

Putative sites of blocker binding to the extracellular surface of human AQP4. Top left panel: zoomed-out side-view of AQP4 showing putative site of arbidol binding based on molecular docking computations. Other panels: zoomed-in en face views of the AQP4 extracellular surface showing binding of arbidol, tamarixetin, and berbamine.

Arbidol and tamarixetin reduce NMO lesions in an ex vivo spinal cord slice model of NMO

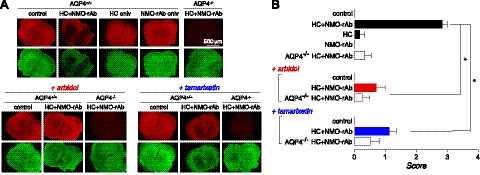

The blockers were tested in a spinal cord slice culture of NMO, in which NMO-rAb and complement produce NMO-like lesions with loss of GFAP and AQP4 immunoreactivity, myelin loss, deposition of activated complement, and microglia activation (32). Initial testing showed that arbidol and tamarixetin at up to 100 μM did not produce pathology when added to spinal cord slice cultures, though berbamine at 25 μM caused astrocyte cytotoxicity and microglial activation. Spinal cord slices were cultured for 7 d, after which NMO-rAb and complement were added with or without test compound (25 μM arbidol or tamarixetin). Following an additional 24 h in culture, slices were immunostained for GFAP and AQP4 and scored for lesion severity. Representative fluorescence micrographs in Fig. 6A and lesion scores in Fig. 6B show significant loss of GFAP and AQP4 immunostaining in NMO-rAb and complement-treated cultures in spinal cord slices from wild-type mice, with little pathology seen in slices from AQP4-knockout mice or in slices from wild-type mice treated with NMO-rAb or complement individually. Arbidol and tamarixetin significantly reduced lesion severity produced by NMO-rAb and complement, but did not cause damage when added alone.

Figure 6.

Arbidol and tamarixetin reduce pathology in an ex vivo spinal cord slice model of NMO. A) Spinal cord slices from mice (wild-type, AQP4+/+; AQP4-knockout, AQP4−/−) were cultured for 7 d, followed by 24 h in the presence of control or NMO-rAb (rAb-53; 10 μg/ml) and/or human complement (HC; 5%), without or with blocker (25 μM). Immunostaining shown for AQP4 (red) and GFAP (green). B) NMO lesion scores. Values are means ± se (n=4–5). *P < 0.001.

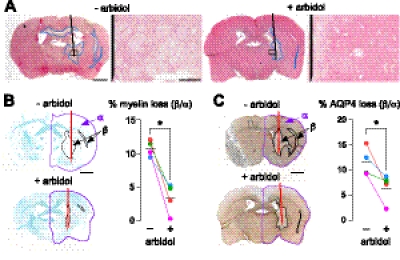

Arbidol reduces NMO lesions in an in vivo mouse model of NMO

Blockers were also tested in an in vivo mouse model in which NMO-like lesions are produced following intracerebral injection of NMO-IgG and complement. Figure 7 shows that injection of NMO-IgG (purified IgG from NMO serum) and complement produced lesions with inflammatory cell infiltration (primarily neutrophils), and loss of AQP4 and myelin in the injected hemisphere. In control experiments, as reported previously (refs. 17, 18 and data not shown), inflammatory cell infiltration and loss of myelin or AQP4 were not seen following intracerebral injection of control (non-NMO) IgG and complement; NMO-IgG alone; NMO-IgG-depleted IgG and complement; and NMO-IgG and complement in AQP4-null mice. Only arbidol was studied, based on preliminary work showing that arbidol did not cause pathology itself, whereas berbamine caused inflammation, as also seen in spinal cord slice cultures, and tamarixetin caused mild edema in the injected hemisphere. Figure 7 shows that arbidol significantly reduced lesion size at 24 h after intracerebral injection of NMO-IgG and complement, as assessed quantitatively by areas of loss of myelin (Fig. 7B) and AQP4 (Fig. 7C). Data are shown for IgG from sera of 4 patients with NMO.

Figure 7.

Arbidol reduces NMO lesions in an in vivo mouse model produced by intracerebral injection of NMO-IgG and human complement. A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Whole brain section (left panel) and magnified view of area in box (right panel). Damaged areas (reduced eosin staining) are outlined in blue. Needle track is shown in black. B) Left panel: Luxol Fast Blue-stained (myelin) brain sections. Right panel: percentage myelin loss (area β/area α) for 4 pairs of mice, each pair injected with complement and IgG purified from serum of a different patient with NMO, without or with arbidol. *P < 0.01. C) Left panel: brain sections immunostained brown for AQP4. Right panel: percentage loss of AQP4 immunostaining for 4 pairs of mice as in B. *P < 0.05. Values are means ± se. Scale bars = 1 mm (left panels); 100 μm (A, right panels).

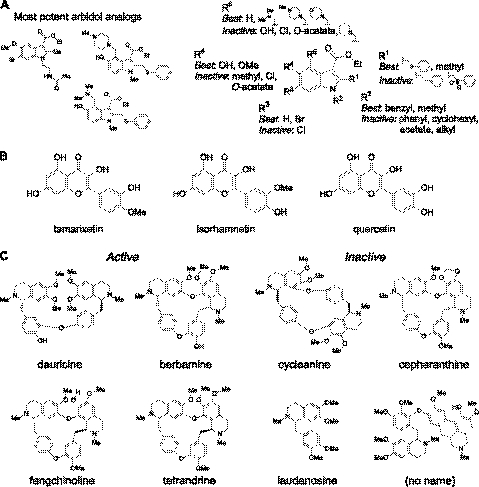

Structural determinants of blocker action

Commercially available chemical analogs of arbidol, tamarixetin, and berbamine were screened in order to establish structure-activity relationships and to potentially identify more potent blockers. Screening of 92 arbidol analogs using the original binding assay yielded 3 compounds that inhibited NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 by >50% at 25 μM (Fig. 8A, left), with the best having ∼2-fold greater potency than arbidol in binding and CDC assays. Figure 8A, right panel, summarizes the structural determinants for blocker activity, suggesting that the arbidol pharmacophore includes benzyl thiophenol, methyl, hydroxyl, and benzyl-amino substituents at R1, R2, R3, and R4 positions, respectively. Figure 8B shows the similar structures of tamarixetin and isorhamnetin, the major metabolites of quercetin. Interestingly, quercetin was inactive, whereas isorhamnetin and tamarixetin had comparable potency. Loss of activity with minimal structural change suggests highly specific binding to the target. A limited set of available berbamine analogs was studied. Figure 8C shows several active benzylisoquinoline dimers, with the most potent being fangchinoline, with ∼2-fold greater potency than berbamine. Monomeric benzylisoquinolines, including laudanosine, were found to be inactive. Comparison of active and inactive compounds suggested that blocking activity required benzyl-to-benzyl or isoquinoline-to-isoquinoline linkage.

Figure 8.

Blocker structure-activity relationships. A) Left panel: structures of 3 active arbidol analogs. Right panel: summary of structural determinants of arbidol blocker activity. B) Structures of active compounds tamarixetin and isorhamnetin and (inactive) parent compound quercetin. C) Structures of active and inactive berbamine analogs.

DISCUSSION

The strategy of blocking an autoantibody-target interaction with small molecules, as reported here for NMO, may be applicable as well to other autoimmune and paraneoplastic diseases, such as myasthenia gravis and anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis, where disease pathogenesis involves autoantibody binding to defined cellular targets. The blocker approach may also be useful in a subset of more complex autoimmune-related disorders, such as juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus, pending the identification of pathogenic antibody-target interactions. NMO is well suited for a blocker approach because its defined target, AQP4, has a small extracellular footprint in which binding of a small molecule could interfere sterically with the binding of polyclonal NMO-IgG in human NMO. Our high-throughput screen identified compounds that inhibited NMO-IgG binding and cytotoxicity in AQP4-expressing cell cultures, and reduced the severity of NMO-IgG/complement-dependent NMO lesions in an ex vivo spinal cord slice culture model and in an in vivo mouse model.

Through several mechanisms, small-molecule blockers could interfere with NMO-IgG binding to cell surface AQP4. Blockers could bind to the AQP4 extracellular surface or to the variable Fab region of the AQP4-targeted NMO-IgG autoantibody. Blockers might act by promoting cellular internalization of AQP4, reducing the amount of surface-exposed AQP4, or by interfering with AQP4 supramolecular assembly in OAPs, as most NMO autoantibodies bind less well to non-OAP-associated AQP4 than to AQP4 in OAPs (24). OAP formation involves AQP4 N-terminal interactions (36), which may be amenable for targeting by a small molecule. The blockers identified here did not reduce AQP4 surface expression or interfere with AQP4 OAP assembly. Blocker efficacy in inhibiting the binding of polyclonal NMO-IgG in multiple NMO serum specimens suggests blocker binding to AQP4 rather than to NMO-IgGs, which was supported by molecular docking computations that identified putative sites of blocker binding on the extracellular AQP4 surface. The lack of blocker effect on antiganglioside antibody CDC further supports the AQP4 selectivity of blocker action. Together, our data suggest that blocker action involves direct binding to the extracellular surface of AQP4, resulting in steric interference with NMO-IgG binding and/or a conformational change in AQP4. Definitive determination of the site of blocker binding will require X-ray structural analysis of blocker/AQP4 cocrystals.

The small molecule screen identified natural, plant-derived products of the berbamine alkaloid (bisbenzylisoquinoline) and flavonoid classes, and a known antiviral compound. Berbamine and the related alkaloid tetrandrine have been used in humans and in animal models of disease. Interestingly, berbamine at 50 mg/kg/d (intraperitoneal) for 7 d in mice reduced the severity of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (37), which was attributed to inhibition of IFN-γ production and action on CD4+ T cells involving altered STAT4 expression. In humans, berbamine alkaloids are reported to have antileukopenia effects, suppress delayed-type hypersensitivity, and slow fibrotic lesions in pulmonary silicosis (38, 39). Tetrandrine and berbamine also inhibit the multidrug resistance transporter MDR1 (40) and have been used in combination with daunorubicin, etoposide, and cytarabinea to treat acute myeloid leukemia (41). Though these reports are largely anecdotal, they suggest that berbamine and tetrandine are well tolerated at high doses in humans. We found here that berbamine alkaloids blocked NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 and prevented cytotoxicity in cell cultures; however, berbamine caused inflammation on its own when applied directly to CNS tissues at concentrations predicted to have therapeutic benefit in NMO. Further work is needed to identify effective and nontoxic berbamine analogs, perhaps out of the >400 known bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids with different linkage geometries, O-methylation and chirality.

Tamarixetin and the closely related compound isorhamnetin were active and nontoxic to spinal cord slice cultures, whereas their parent compound, quercetin, was inactive. Quercetin is a plant-derived, polyphenolic compound present in vegetables, fruits, tea, and wine. Quercetin is a widely available neutraceutical with reported beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases (42, 43). Following oral administration, quercetin is metabolized rapidly by O-methylation to tamarixetin (4′OCH3-quercetin) and isorhamnetin (3′OCH3-quercetin) (44). A pharmacokinetic study in humans showed maximal serum concentration of quercetin and isorhamnetin of ∼250 and 50 nM, respectively, with half-life of 2.5–5 h (45). Rats fed a chronic 1% quercetin diet had tissue concentrations of tamarixetin and isorhamnetin of up to 5–10 nmol/g, but ∼10-fold lower in brain (46). Thus, though quercetin is well tolerated at high oral doses, serum and tissue concentrations of its metabolites are substantially lower than those needed for reducing NMO-IgG binding to AQP4.

Arbidol is a broad-spectrum antiviral compound used in Russia and China for prevention and treatment of influenza and other respiratory viral infections (47) but not currently approved in the United States or Europe. Arbidol has also shown antiviral activity in vitro against HCV (48), hepatitis B (49), and rhinovirus (50). The putative mechanism of arbidol action involves inhibition of virus-mediated cell fusion and entry. Oral administration of arbidol in rats showed rapid appearance in blood and peripheral organs, though relatively little in brain (51). In humans, a single oral administration of 200 mg arbidol gave a maximum serum concentration of 420 ng/ml (∼1 μM) with a half-life of 6 h (52). Based on numerous studies, arbidol is well tolerated in adults and children. Arbidol and more potent arbidol analogs warrant further preclinical evaluation for potential NMO therapy.

Though the results here provide proof of concept that small-molecule blockers of NMO-IgG binding to cellular AQP4 can be identified that reduce NMO pathology in cell and animal models, many challenges remain in translating these initial results into drug therapy for NMO. As for small-molecule development programs in general, the blockers identified here, and by additional screening, should have suitable potency and pharmacological properties to give sustained therapeutic concentration at their target sites without toxicity, both for short-term treatment of acute exacerbations and for long-term oral administration. As NMO is a disease of the CNS, drug penetration into the CNS is another consideration, though local disruption of the blood-brain barrier at the site of an NMO lesion may allow targeted accumulation of a non-CNS-penetrable drug where needed. A topical ocular preparation might be useful for acute therapy or prophylaxis of optic neuritis in NMO. Because blockers of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 do not affect circulating levels of NMO-IgG, greatest clinical benefit might be afforded by combination therapy of a blocker together with currently used therapy (anti-B-cell monoclonal antibody, plasmapheresis, immunosuppression) to reduce serum NMO-IgG and downstream neuroinflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation (to A.S.V., M.C.P., and J.L.B.); grants EY13574, EB00415, DK35124, HL73856, DK86125, and DK72517 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (to A.S.V.); and grant RG4320 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (to J.L.B.).

Footnotes

- ADCC

- antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- AQP4

- aquaporin-4

- CDC

- complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- CNS

- central nervous system

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- FRT

- Fisher rat thyroid

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acid protein

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- NMO

- neuromyelitis optica

- NMO-IgG

- neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G

- NMO-rAb

- neuromyelitis optica recombinant monoclonal antibody

- OAP

- orthogonal array of particles

- Pf

- osmotic water permeability coefficient

- TIRFM

- total internal reflection flurorescence microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wingerchuk D. M., Lennon V. A., Lucchinetti C. F., Pittock S. J., Weinshenker B. G. (2007) The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 6, 805–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lennon V. A., Kryzer T. J., Pittock S. J., Verkman A. S., Hinson S. R. (2005) IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J. Exp. Med. 202, 473–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nielsen S., Nagelhus E. A., Amiry-Moghaddam M., Bourque C., Agre P., Ottersen O. P. (1997) Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 17, 171–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verkman A. S., Ratelade J., Rossi A., Zhang H., Tradtrantip L. (2011) Aquaporin-4: orthogonal array assembly, CNS functions, and role in neuromyelitis optica. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 702–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manley G. T., Fujimura M., Ma T., Noshita N., Filiz F., Bollen A. W., Chan P., Verkman A. S. (2000) Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat. Med. 6, 159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Papadopoulos M. C., Manley G. T., Krishna S., Verkman A. S. (2004) Aquaporin-4 facilitates reabsorption of excess fluid in vasogenic brain edema. FASEB J. 18, 1291–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Binder D. K., Yao X., Zador Z., Sick T. J., Verkman A. S., Manley G. T. (2006) Increased seizure duration and slowed potassium kinetics in mice lacking aquaporin-4 water channels. Glia 53, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Padmawar P., Yao X., Bloch O., Manley G. T., Verkman A. S. (2005) K+ waves in brain cortex visualized using a long-wavelength K+-sensing fluorescent indicator. Nat. Methods 2, 825–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Auguste K. I., Jin S., Uchida K., Yan D., Manley G. T., Papadopoulos M. C., Verkman A. S. (2007) Greatly impaired migration of implanted aquaporin-4-deficient astroglial cells in mouse brain toward a site of injury. FASEB J. 21, 108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saadoun S., Papadopoulos M. C., Watanabe H., Yan D., Manley G. T., Verkman A. S. (2005) Involvement of aquaporin-4 in astroglial cell migration and glial scar formation. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5691–5698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li L., Zhang H., Varrin-Doyer M., Zamvil S. S., Verkman A. S. (2011) Proinflammatory role of aquaporin-4 in autoimmune neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 25, 1556–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cree B. (2008) Neuromyelitis optica: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 8, 427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jarius S., Paul F., Franciotta D., Waters P., Zipp F., Hohlfeld R., Vincent A., Wildemann B. (2008) Mechanisms of disease: aquaporin-4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 4, 202–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bennett J. L., Lam C., Kalluri S. R., Saikali P., Bautista K., Dupree C., Glogowska M., Case D., Antel J. P., Owens G. P., Gilden D., Nessler S., Stadelmann C., Hemmer B. (2009) Intrathecal pathogenic anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies in early neuromyelitis optica. Ann. Neurol. 66, 617–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bradl M., Misu T., Takahashi T., Watanabe M., Mader S., Reindl M., Adzemovic M., Bauer J., Berger T., Fujihara K., Itoyama Y., Lassmann H. (2009) Neuromyelitis optica: pathogenicity of patient immunoglobulin in vivo. Ann. Neurol. 66, 630–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kinoshita M., Nakatsuji Y., Kimura T., Moriya M., Takata K., Okuno T., Kumanogoh A., Kajiyama K., Yoshikawa H., Sakoda S. (2009) Neuromyelitis optica: Passive transfer to rats by human immunoglobulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 623–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saadoun S., MacDonald C., Waters P., Bell B. A., Vincent A., Verkman A. S., Papadopoulos M. C. (2012) Neutrophil protease inhibition greatly reduces NMO-IgG-induced inflammation and myelin loss in mouse brain. [E-pub ahead of print] Ann. Neurol. doi: 10.1002/ana.22686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saadoun S., Waters P., Bell B. A., Vincent A., Verkman A. S., Papadopoulos M. C. (2010) Intra-cerebral injection of neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G and human complement produces neuromyelitis optica lesions in mice. Brain 133, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang H., Bennett J. L., Verkman A. S. (2011) Ex vivo spinal cord slice model of neuromyelitis optica reveals novel immunopathogenic mechanisms. Ann. Neurol. 70, 943–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hinson S. R., Pittock S. J., Lucchinetti C. F., Roemer S. F., Fryer J. P., Kryzer T. J., Lennon V. A. (2007) Pathogenic potential of IgG binding to water channel extracellular domain in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 69, 2221–2231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marignier R., Nicolle A., Watrin C., Touret M., Cavagna S., Varrin-Doyer M., Cavillon G., Rogemond V., Confavreux C., Honnorat J., Giraudon P. (2010) Oligodendrocytes are damaged by neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G via astrocyte injury. Brain 133, 2578–2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parratt J. D., Prineas J. W. (2010) Neuromyelitis optica: a demyelinating disease characterized by acute destruction and regeneration of perivascular astrocytes. Mult. Scler. 16, 1156–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tradtrantip L., Zhang H., Saadoun S., Phuan P., Lam C., Papadopoulos M. C., Bennett J. L., Verkman A. S. (2012) Anti-aquaporin-4 monoclonal antibody blocker therapy for neuromyelitis optica. [E-pub ahead of print] Ann. Neurol. doi: 10.1002/ana.22657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crane J. M., Lam C., Rossi A., Gupta T., Bennett J. L., Verkman A. S. (2011) Binding affinity and specificity of neuromyelitis optica autoantibodies to aquaporin-4 M1/M23 isoforms and orthogonal arrays. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16516–16524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wingerchuk D. M., Lennon V. A., Pittock S. J., Lucchinetti C. F., Weinshenker B. G. (2006) Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 66, 1485–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crane J. M., Bennett J. L., Verkman A. S. (2009) Live cell analysis of aquaporin-4 M1/M23 interactions and regulated orthogonal array assembly in glial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35850–35860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tajima M., Crane J. M., Verkman A. S. (2010) Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) associations and array dynamics probed by photobleaching and single-molecule analysis of green fluorescent protein-AQP4 chimeras. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8163–8170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang B., Zhang H., Verkman A. S. (2008) Lack of aquaporin-4 water transport inhibition by antiepileptics and arylsulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 7489–7493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma T., Yang B., Gillespie A., Carlson E. J., Epstein C. J., Verkman A. S. (1997) Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 957–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ho J. D., Yeh R., Sandstrom A., Chorny I., Harries W. E., Robbins R. A., Miercke L. J., Stroud R. M. (2009) Crystal structure of human aquaporin 4 at 1.8 Å and its mechanism of conductance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 7437–7442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin B. J., Rossi A., Verkman A. S. (2011) Model of aquaporin-4 supramolecular assembly in orthogonal arrays based on heterotetrameric association of M1–M23 isoforms. Biophys. J. 100, 2936–2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mader S., Lutterotti A., Di Pauli F., Kuenz B., Schanda K., Aboul-Enein F., Khalil M., Storch M. K., Jarius S., Kristoferitsch W., Berger T., Reindl M. (2010) Patterns of antibody binding to aquaporin-4 isoforms in neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One 5, e10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolburg H., Wolburg-Buchholz K., Fallier-Becker P., Noell S., Mack A. F. (2011) Structure and functions of aquaporin-4-based orthogonal arrays of particles. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 287, 1–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jarius S., Wildemann B. (2010) AQP4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica: diagnostic and pathogenetic relevance. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pukel C. S., Lloyd K. O., Travassos L. R., Dippold W. G., Oettgen H. F., Old L.J. (1982) GD3, a prominent ganglioside of human melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 155, 1133–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crane J. M., Verkman A. S. (2009) Determinants of aquaporin-4 assembly in orthogonal arrays revealed by live-cell single-molecule fluorescence imaging. J. Cell Sci. 122, 813–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ren Y., Lu L., Guo T. B., Qiu J., Yang Y., Liu A., Zhang J. Z. (2008) Novel immunomodulatory properties of berbamine through selective down-regulation of STAT4 and action of IFN-gamma in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 181, 1491–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li Q. L., Xu Y. H., Zhou Z. S., Chen X. W., Huang X. G., Chen S. L., Zhan C. X. (1981) The therapeutic effect of tetrandrine on silicosis. Chin. J. Tuberc. Resp. Dis. 4, 321–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu C. X., Xiao P. G., Liu G. S. (1991) Studies on plant resources, pharmacology and clinical treatment with berbamine. Phytother. Res. 5, 228–230 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei Y. L., Xu L., Liang Y., Xu X. H., Zhao X. Y. (2009) Berbamine exhibits potent antitumor effects on imatinib-resistant CML cells in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu W. L., Shen H. L., Ao Z. F., Chen B. A., Xia W., Gao F., Zhang Y. N. (2006) Combination of tetrandrine as a potential-reversing agent with daunorubicin, etoposide and cytarabine for the treatment of refractory and relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia Res. 30, 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arts I. C., Hollman P. C. (2005) Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 317S–325S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hertog M. G., Feskens E. J., Hollman P. C., Katan M. B., Kromhout D. (1993) Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet 342, 1007–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van der Woude H., Boersma M. G., Vervoort J., Rietjens I. M. (2004) Identification of 14 quercetin phase II mono- and mixed conjugates and their formation by rat and human phase II in vitro model systems. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 17, 1520–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schulz H. U., Schurer M., Bassler D., Weiser D. (2005) Investigation of pharmacokinetic data of hypericin, pseudohypericin, hyperforin and the flavonoids quercetin and isorhamnetin revealed from single and multiple oral dose studies with a hypericum extract containing tablet in healthy male volunteers. Arzneimittelforschung 55, 561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Boer V. C., Dihal A. A., van der Woude H., Arts I. C., Wolffram S., Alink G. M., Rietjens I. M., Keijer J., Hollman P. C. (2005) Tissue distribution of quercetin in rats and pigs. J. Nutr. 135, 1718–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boriskin Y. S., Leneva I. A., Pecheur E. I., Polyak S. J. (2008) Arbidol: a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that blocks viral fusion. Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boriskin Y. S., Pecheur E. I., Polyak S. J. (2006) Arbidol: a broad-spectrum antiviral that inhibits acute and chronic HCV infection. Virol. J. 3, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chai H., Zhao Y., Zhao C., Gong P. (2006) Synthesis and in vitro anti-hepatitis B virus activities of some ethyl 6-bromo-5-hydroxy-1H-indole-3-carboxylates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lavillette D., Bartosch B., Nourrisson D., Verney G., Cosset F. L., Penin F., Pecheur E. I. (2006) Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate low pH-dependent membrane fusion with liposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3909–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Glushkov R.G. (1992) Arbidol antiviral immunostimulant interferon inducer. Drugs Fut. 17, 1079–1081 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu M. Y., Wang S., Yao W. F., Wu H. Z., Meng S. N., Wei M. J. (2009) Pharmacokinetic properties and bioequivalence of two formulations of arbidol: an open-label, single-dose, randomized-sequence, two-period crossover study in healthy Chinese male volunteers. Clin. Ther. 31, 784–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]