Abstract

These studies were undertaken to extend emerging evidence that β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) agonists, in addition to their bronchorelaxing effects, may have broad anti-inflammatory effects in the lung following onset of experimental acute lung injury (ALI). Young male C57BL/6 mice (25 g) developed ALI following airway deposition of bacterial LPS or IgG immune complexes in the absence or presence of appropriate stereoisomers (enantiomers) of β2AR agonists, albuterol or formoterol. Endpoints included albumin leak into lung and buildup of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and cytokines/chemokines in bronchoalveolar fluids. Both β2AR agonists suppressed lung inflammatory parameters (IC50=10−7 M). Similar effects of β2AR agonists on mediator release were found when mouse macrophages were stimulated in vitro with LPS. The protective effects were associated with reduced activation (phosphorylation) of JNK but not of other signaling proteins. Collectively, these data suggest that β2AR agonists have broad anti-inflammatory effects in the setting of ALI. While β2AR agonists suppress JNK activation, the extent to which this can explain the blunted lung inflammatory responses in the ALI models remains to be determined.—Bosmann, M., Grailer, J. J., Zhu, K., Matthay, M A., Vidya Sarma, J., Zetoune, F. S., Ward, P. A. Anti-inflammatory effects of β2 adrenergic receptor agonists in experimental acute lung injury.

Keywords: albuterol, formoterol, macrophages, neutrophils, JNK

Acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are conditions of acute inflammatory injury in human lungs, associated with polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) accumulation in alveolar spaces and in adjacent capillaries, together with fibrin deposits and edema fluid in the same areas. The presence of C5a and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALFs) indicates that complement activation occurs during ALI and ARDS (1). These inflammatory responses are, as expected, associated with defective gas exchange between alveolar spaces and blood in the interstitial capillaries of the lung. The frequency of ALI in the United States is ∼200,000 cases/yr, with a mortality that approaches 40% (2). In some cases of ALI and ARDS, permanent fibrosis or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (in infants) develops, resulting in disabling lung function. Since the causes of ALI and ARDS are poorly understood, treatment is currently limited to supportive therapy.

The initial line of evidence to suggest that the use of β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) agonists produce beneficial effects during ALI and ARDS was related to their ability to enhance clearance of alveolar edema fluid (3, 4). There is emerging evidence that transmitters of the cholinergic autonomic nervous system function in an anti-inflammatory manner, suppressing release of proinflammatory mediators from macrophages (5). Recently, we reported that the adrenergic system, via interaction of α2 adrenergic receptors with catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine), brings about a proinflammatory outcome associated with intensified lung inflammatory injury (6). It was also shown that catecholamines are produced by phagocytes (neutrophils and macrophages). β2AR agonists (such as albuterol) have long been used to induce upper airway bronchorelaxation via induction of cAMP in bronchial smooth muscle cells in humans with obstructive pulmonary diseases, such as asthma (7). There are suggestions that β2AR agonists have additional actions in varying circumstances, such as enhancing clearance of pulmonary edema fluid in individuals with high-altitude sickness (8) and in animals after acid aspiration (9). The agonists also attenuate the effects of lung ischemia (10) and inhibit pulmonary inflammation after inhalation of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in humans (11). A common explanation for the diverse effects of β2AR agonists is elusive. In the current studies, we found that β2AR agonists have potent anti-inflammatory effects in experimental models of ALI, the outcomes being related to reduced levels in lung of proinflammatory mediators (chemokines, cytokines) and diminished accumulation of neutrophils in lung. While the presence of β2AR agonists suppressed Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation by ∼30–40% and not other signaling molecules, it remains to be proven whether this is the predominant reason for the anti-inflammatory effects of the β2AR agonists. Broadly, these findings may have therapeutic applications for ALI/ARDS and other lung inflammatory conditions in humans (e.g., hypoxia, ischemia, transplant rejection, asthma, etc.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6J and IL-10−/− mice (6–10 wk, 25 g) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. All procedures were performed in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines and the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals, University of Michigan.

Models of ALI

For LPS-induced ALI (LPS-ALI), mice were anesthetized (12, 13), the trachea was surgically exposed, and 40 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 μg LPS (Escherichia coli, O111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was slowly injected intratracheally during inspiration. Sham-treated mice received 40 μl PBS intratracheally. IgG immune complex (IgGIC)-induced ALI (IgGIC-ALI) mice received 125 μg rabbit anti-bovine serum albumin (BSA) IgG (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) intratracheally, followed by intravenous injection of 0.5 mg BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). At the end of experiments, the lungs were flushed with 1 ml PBS to obtain BALFs. After centrifugation, BALF cells were counted in a hemocytometer, and cell-free BALF was stored at −80°C.

Histopathology

Lungs were fixed in 10% formalin overnight, and 3-μm paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Digital images (×40/0.9, ×100/1.4) were acquired using an Olympus BH2 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA).

Isolation and incubation of macrophages

Thioglycollate-elicited murine macrophages were obtained and cultured, and supernatant fluids were harvested, as described elsewhere (12). For isolation of alveolar macrophages, the lungs were lavaged multiple times with PBS (0.5 mM EDTA). The mouse lung alveolar epithelial cell line 12 (MLE-12) and SV40-transformed mouse macrophage line (MH-S) cells were gifts from Dr. J. Weinberg (University of Michigan).

Measurement of BALF albumin and mediator concentrations

Mouse albumin in BALF was detected by ELISA (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA). Mouse cytokines and chemokines were detected with a bead-based multiplex assay (Bio-Plex Pro; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), as described earlier (13). In addition, mouse IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α were measured by ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Analysis of signaling pathways

Macrophages were lysed (Bio-Plex Cell Lysis Kit; Bio-Rad), and the following signaling pathways were analyzed with phosphorylation-specific antibodies in a bead-based assay format (Bio-Plex Phospho 9-Plex; Bio-Rad): Akt (Ser473), c-Jun (Ser63), CREB (Ser133), ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, Thr185/Tyr187), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), MEK1 (Ser217/Ser221), NF-κB (Ser536), p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), and STAT3 (Ser727).

Reagents

The following reagents were used: LPS (E. coli, 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich); R-albuterol, S-albuterol, R,R-formoterol and S,S-formoterol (kindly provided by Sepracor Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA); SP600125 (JNK inhibitor with IC50=40 nM for JNK-1 and JNK-2, IC50=90 nM for JNK-3; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA); 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine and SQ22536 (adenylate cyclase inhibitors; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); neutralizing monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-10 IgG1 and rat IgG2 isotype control antibodies (R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means ± se. Data sets were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA or Student's t test (GraphPad Prism 5.03; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and differences were considered significant at values of P < 0.05. In vitro experiments were performed independently ≥3 times, and n ≥ 5 mice/group were used for in vivo experiments.

RESULTS

Effects of β2AR agonists on ALI following deposition of IgGIC or LPS

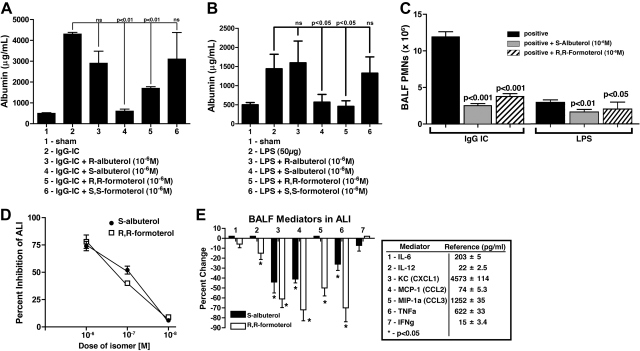

To obtain data related to the anti-inflammatory activities of β2AR agonists, the experiments described in Fig. 1 were carried out. In Fig. 1A, ALI was induced by intrapulmonary deposition of IgGICs, and injury was quantified by levels of mouse albumin in BALFs. Details of these models are described elsewhere (14, 15). It is clear that only certain stereoisomers (enantiomers) of albuterol and formoterol suppressed the albumin leak, namely, S-albuterol and R,R-formoterol (Fig. 1A, bars 4 and 5). The compounds by themselves had no effect on albumin content in BALFs (data not shown). When the ALI model using LPS was employed, remarkably similar patterns of suppression of LPS-induced ALI (reduced albumin leak into the alveolar compartment) were found, with S-albuterol and R,R-formoterol being highly suppressive (Fig. 1B). The severity of lung damage (albumin leakage, PMN counts) was more intensive in IgGIC-ALI as compared to LPS-ALI, which is consistent with our earlier reports on these two ALI models. Figure 1C shows that the lung instillation of 10−6M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol greatly suppressed buildup of PMNs (nearly 70%) in BALFs during IgGIC-induced ALI and in LPS-induced ALI. It is well documented that the IgGIC and LPS models of ALI require participation of PMNs (16). Figure 1D demonstrates dose-response curves for β2AR agonist inhibition of ALI induced by IgGICs, as measured by albumin buildup in BALFs. The IC50 values for S-albuterol and R,R-formoterol effects in lung were ∼10−7M. Finally, using the IgGIC model of ALI, the data in Fig. 1E demonstrate the effects of the presence in BALFs of either of the two β2AR agonists (10−6M) on the buildup of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in BALFs, several of which are required for recruitment of PMNs and full development of ALI (reviewed in ref. 16). The data are expressed as percentage reduction in mediator levels, and the positive control values (pg/ml) are indicated for each mediator. Minimal effects were seen on levels of IL-6 and IL-12 (Fig. 1E, bars 1 and 2). The most consistent reductions caused by β2AR agonists (especially R,R-formoterol) involved KC (CXCL1), MCP-1 (CCL2), and TNF-α, all of which have been shown to play a facilitative role in this type of ALI (16). Accordingly, it seems that the suppressive effects on β2AR agonists in this ALI model appear to be linked to a reduction in cytokine and chemokine levels. Such mediators are known to be required for PMN recruitment and PMN activation, as well as activation of lung macrophages.

Figure 1.

Effects of β2AR agonists during ALI. A) Acute lung injury in young adult (25 g) C57BL/6 male mice 6 h after intratracheal (i.t.) administration of 125 μg anti-BSA IgG and intravenous (i.v.) infusion of 1 mg BSA, resulting in IgGIC-induced ALI. Sham-treated mice received i.t. anti-BSA but no i.v. BSA. Isomeric forms (enantiomers) of β2AR agonists were intermixed with the anti-BSA, all at 10−6 M. For each bar, n ≥ 12 mice. Endpoints were BALF mouse albumin as measured by ELISA. B) ALI induced by i.t. administration of 50 μg LPS 6 h earlier, resulting in ALI. Various enantiomers of albuterol were used (as indicated), at 10−6 M, similar to the protocol in panel A. For each bar, n ≥ 10 mice. Endpoints were mouse albumin in BALFs. C) Effects of 10−6 M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol on BALF content of PMNs 6 h after onset of IgGIC-induced or LPS-induced ALI. Virtually no PMNs were found in sham-treated BALFs. For each bar, n ≥ 10. D) Dose responses of S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol (i.t.) on BALF albumin 6 h after onset of IgGIC-ALI. For each dose, n ≥ 5 mice. BALF albumin levels were compared as a percentage of albumin in positive controls. E) BALF mediators in IgGIC-ALI mice 6 h after onset of reactions, expressed as a percentage of positive controls (pg/ml; shown at right). S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol were present at 10−6 M. Positive control reference values (pg/ml) are indicated for each of the 7 mediators. For each bar, n ≥ 6 mice. *P < 0.05.

Effects of β2AR agonists on in vitro production of macrophage mediators and signaling molecules

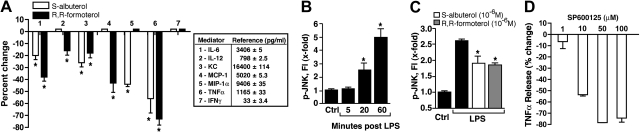

In Fig. 2, we switched to in vitro use of LPS-stimulated mouse peritoneal exudate (thioglycollate)-induced macrophages (PEMs) in the presence or absence of β2AR agonists or selective JNK inhibitor SP600125. In Fig. 2A, the presence of 10−6 M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol consistently caused reduced levels of IL-6 (bar 1), KC (CXCL1; bar 3), and TNF-α (bar 6) in supernatant fluids of LPS-treated macrophages. KC and TNF-α have been shown to be important mediators for recruitment of PMNs and activation of lung macrophages in the ALI model employed (17, 18). In Fig. 2B, PEMs were incubated with LPS, and activation (phosphorylation) of JNK was determined as a function of time, using the bead-based assay system. Preliminary studies showed that phosphorylation of signaling proteins occurred during the first 60 min after addition of LPS to PEMs (data not shown). It was clear that by 20 min, phospho-JNK was elevated, with a doubling of activation by 60 min (Fig. 2B). When PEMs were incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C, there was 2.5-fold increase in phosphorylation of JNK (Fig. 2C), whereas in the copresence of 10−6 M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol, there were reductions (shown as means) based on 4 separate experiments in phospho-JNK of ∼31 and 35%, respectively. In companion experiments, LPS-stimulated macrophages were incubated in the absence or presence of 10−5, 10−6, or 10−7M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol, and changes in phospho-JNK were assessed. The phospho-amino acids of the following signaling molecules were also evaluated after LPS activation in the absence or presence of 10−6M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol: Akt (Ser473), CREB (Ser133), ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, Thr185/Tyr187), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), MEK1 (Ser217/Ser221), NF-κB (Ser536), p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), STAT3 (Ser727). Surprisingly, the only signaling molecule consistently affected by β2AR agonists was phospho-JNK.

Figure 2.

Effects of β2AR agonists and JNK inhibitors on mediator production in vitro. A) Effects of β2AR agonists on mediator production in LPS-stimulated (1 μg/ml) mouse PEMs (2×106) for 4 h at 37°C, expressed as percentage reduction. Positive control reference values (pg/ml) are indicated for each of the 7 mediators. As indicated, 10−6 M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol was present at the time of addition of LPS to PEMs. Percentage reduction is relative to LPS-stimulated PEM in the absence of β2AR agonists. Reference values (pg/ml) for positive controls are shown in box. For each bar, n = 6 samples. B) Activation (phosphorylation) of JNK in LPS-stimulated PEMs as a function of time, using control (ctrl) PEMs (non-LPS exposed) as the reference point. Phospho-JNK was measured in cell lysates as a function of time (min) after addition of LPS, using a bead-based assay. For each bar, n = 4 samples. C) Levels of phospho-JNK in LPS-stimulated PEMs in the absence or presence of 10−6 M S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol 60 min after addition of LPS ± β2AR agonists. Results are from 4 separate experiments, in which average reductions of JNK phosphorylation in the presence of S-albuterol or R,R-formoterol were 31 and 35%, respectively. For each bar, n ≥ 4 samples. D) Dose response for SP600125 (JNK1/2 inhibitor) on release of TNF-α from LPS-stimulated PEMs. For each bar, n ≥ 4 samples. *P < 0.05.

We also employed SP600125, a selective, reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of JNK (19). PEMs were activated by LPS in the absence or presence of SP600125 (1.0–100 μM), and effects on TNF-α release were determined and expressed as percentage reduction (Fig. 2D). As is apparent, this JNK inhibitor had an IC50 of ∼10 μM. Collectively, these data suggest that the inhibitory effects of β2AR agonists on LPS-mediated release of TNF-α and other mediators from PEMs may be linked to the ability of these agonists to suppress JNK activation.

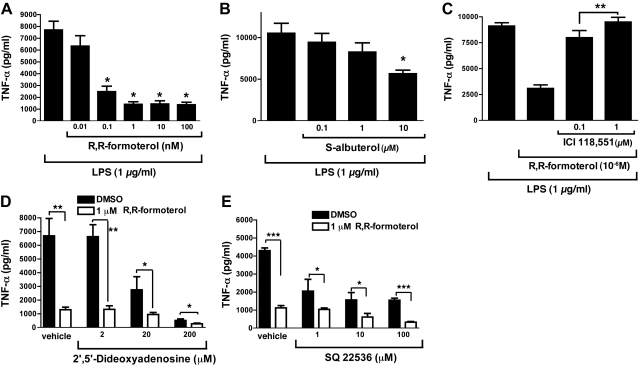

Additional studies were done to further define the suppressive effects of β2AR agonists on TNF-α release from LPS-activated PEMs. In Fig. 3A, R,R-formoterol was used in a range of 0.01–100 nM. The IC50 for this β2AR agonist in terms of reduced release of TNF-α was 0.07 nM, while the IC50 for S-albuterol was much higher (12 μM; Fig. 3B). When supernatant fluids from LPS-stimulated macrophages (shown in Fig. 3A, B) were assayed for other mediators relevant to IgGIC- and LPS-induced ALI, we found that for release of MCP-1, MIP-1α, KC, and IL-6, the IC50 values for R,R-formoterol were 0.6, 0.85, 1.0, and 0.8 nM, respectively (data not shown). For S-albuterol, the in vitro IC50 values were 2, 1, >10, and >10 μM, respectively. Accordingly, R,R-formoterol had broad inhibitory effects on mediator release from macrophages, while S-albuterol was much less effective. Why the β2AR agonists were equally inhibitory in vivo (Fig. 1D) but showed different efficacy in vitro (Figs. 2 and 3) is not known. In Fig. 3C, the selective β2AR antagonist ICI-118,551 was used at 0.1 or 1.0 μM in the copresence of 10−6 M R,R-formoterol. It was clear that the presence of this compound largely blocked the ability of R,R-formoterol to suppress TNF-α release from LPS-stimulated PEMs, which is consistent with R,R-formoterol working via β2AR. Because the β2AR agonists used in these studies have been well documented to cause bronchial smooth muscle relaxation via induction of cAMP (20), studies were carried out to determine whether production of cAMP in LPS-stimulated PEMs might be linked to the suppressive effects of β2AR agonists on TNF-α release from PEMs. The experiments described in Fig. 3D, E were performed. PEMs were stimulated with LPS in the absence or presence of 1 μM R,R-formoterol, and TNF-α release after 4 h was evaluated. The copresence of the adenylate cyclase inhibitors 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine (2–200 μM; Fig. 3D) or SQ22536 (1–100 μM; Fig. 3E) failed to reverse the inhibitory effects of R,R-formoterol on TNF-α release from PEMs. TNF-α release was suppressed by nearly 80% in the presence of the β2AR agonist, and no reversal in this suppression was found in the presence of 2 μM 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine. Similarly, SQ22536 did not reverse the suppressive effects of R,R-formoterol on TNF-α. At higher doses, in the absence of R,R-formoterol, both inhibitors caused nonspecific reductions in LPS-induced release of TNF-α. The data suggest that the suppressive effects of R,R-formoterol are probably not linked to cAMP induction.

Figure 3.

In vitro dose responses of LPS-stimulated PEMs in the absence or presence of β2AR agonists, using release of TNF-α as the endpoint. A) TNF-α release in the presence of increasing concentrations of R,R-formoterol (0.01–100 nM). B) Similar experiments using S-albuterol (0.1–10 μM). Text describes parallel effects on MCP-1, MIP-1α, KC, and IL-6. C) Similar experiments with R,R-formoterol (1 μM) in the absence or presence of ICI-118,551 (selective β2AR antagonist). D) Release of TNF-α from PEMs activated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 4 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of 1 μM R,R-formoterol and, as indicated, in the copresence of 1–200 μM 2′,5′dideoxyadenosine (inhibitor of adenylate cyclase). E) Experiments similar to those in D, using another adenylate cyclase inhibitor (SQ2536) at concentrations of 1–100 μM. For all bars, n ≥ 5 samples. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Next, we used MLE-12 cells. MLE-12 cells produced abundant MCP-1 (CCL2) and KC (CXCL1) when stimulated with LPS, but the presence of 10−6 M R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol did not result in impaired mediator release (data not shown). This is despite the fact that alveolar epithelial cells are known to contain abundant expression levels of β2AR, which are required for clearance of intra-alveolar edema fluid (21). Clearly, mediator release from LPS-stimulated MLE-12 cells was not reduced in the presence of 10−6 M R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol.

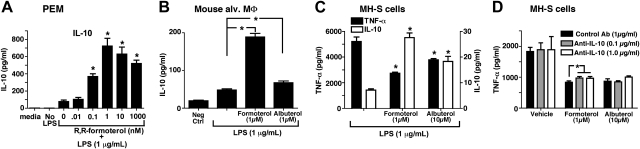

Relevance of the induction of IL-10 to the suppressive effects of β2AR agonists

We wanted to assess whether the suppressive effects of β2AR agonists on macrophages were mediated through IL-10 production, which is known to inhibit cytokine production by activated macrophages (22). When PEMs (1×106) were stimulated in vitro with LPS (1 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of R,R-formoterol (0.01–1,000 nM), PEMs produced IL-10 in the copresence of LPS and R,R-formoterol, while production of IL-10 with PEMs exposed to LPS in the absence of R,R-formoterol was very low (<100 pg/ml; Fig. 4A). When freshly harvested mouse alveolar macrophages were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml), the cells produced IL-10 in the copresence of 1 μM R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol, with 6.5-fold and 2.0-fold increases in IL-10, respectively, compared to treatment with LPS alone (Fig. 4B). MH-S cells were also found to produce IL-10 after LPS addition in the copresence of R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol (Fig. 4C). As expected, R,R-formoterol and S-albuterol reduced TNF-α production by 56 and 10%, respectively (Fig. 4C, solid bars; TNF-α concentrations shown on left y axis). When IL-10 was measured in the same supernatant fluids, R,R-formoterol and S-albuterol enhanced IL-10 production by 3.0-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 4C, open bars; IL-10 concentrations shown on right y axis). These data are similar to the patterns found with alveolar macrophages and PEMs (Figs. 4B and 3A, B). Companion studies were done to determine whether the presence of neutralizing antibody to mouse IL-10 would reverse the suppressed levels of TNF-α released by LPS-stimulated MH-S cells in the presence of R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol. As shown in Fig. 4D, there was no convincing evidence that IL-10 neutralization was able to reverse the inhibitory effect of the β2AR agonists at the time points studied. Finally, when PEMs were obtained from wild-type and IL-10−/− mice and stimulated with LPS, the presence of 10−6 M R,R-formoterol still reduced TNF-α production in wild-type cells by nearly 80% (data not shown). That R,R-formoterol was able to suppress TNF-α production in IL-10−/− PEMs suggests that its ability to reduce TNF-α production is not associated with release of IL-10.

Figure 4.

Suppression of TNF-α production by β2AR agonists is independent of IL-10. A, B) Production of IL-10 by LPS-stimulated mouse PEMs (A) and mouse alveolar macrophages (MΦ; B). Cells were stimulated by LPS (1 μg/ml) for 4 h in the absence or presence of R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol (both at 10−6 M). C) Production of TNF-α (solid bars, left y axis) and IL-10 (open bars, right y axis) in LPS-stimulated MH-S cells (immortalized mouse lung macrophages) in the presence or absence of 1 × 10−6 M R,R-formoterol or S-albuterol, 4 h. D) Similarly treated cells were also exposed to LPS in the presence or absence of 2 different concentrations of neutralizing antibody to IL-10 at the indicated concentrations. For all bars, n ≥ 5 samples. *P < 0.05.

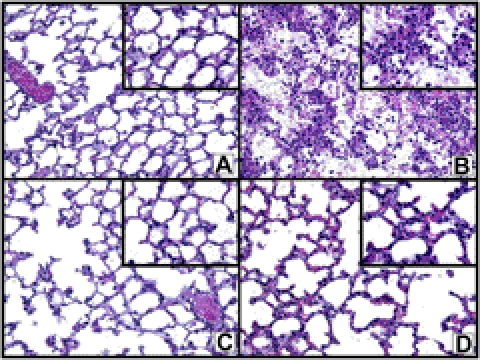

Histopathology of lungs

Figure 5 contains the histopathological features in ALI lungs at 6 h after deposition of IgGICs, using hematoxylin-and-eosin stains on paraffin-embedded sections. In Fig. 5A, the section from normal lung showed alveoli devoid of edema fluid, fibrin deposits, red blood cells (RBCs), and PMNs. In striking contrast, in the positive controls (Fig. 4B), the alveolar spaces showed extensive hemorrhage, fibrin deposits, and PMN accumulations together with edema. The protective features of β2AR agonists are shown in Fig. 5C (S-albuterol) and Fig. 5D (R,R-formoterol), where there were PMNs in the interstitial capillaries but very few in alveolar spaces, which were also largely devoid of fibrin deposits and RBCs.

Figure 5.

Histopathology of mouse lungs in normal lungs and lungs after ALI following airway deposition of IgGICs. A) Histological features of normal mouse lung. B) Positive control (acutely injured lung induced by airway deposition of IgGICs) 6 h after induction of ALI. C, D) Lungs after initiation of ALI in the copresence of 10−6 M S-albuterol (C) or R,R-formoterol (D). All panels are from paraffin-embedded sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×40 view). Insets: ×100 view.

DISCUSSION

There are suggestions in the literature that β2AR agonists may have anti-inflammatory effects in lung. For instance, histamine-induced extravasation of plasma protein in guinea-pig skin was reduced in the presence of either albuterol or formoterol (23). When guinea-pig lungs were exposed in vitro to histamine or bradykinin, the vascular leak was attenuated in the copresence of either β2AR agonist (23). In humans with pulmonary edema associated with high-altitude acute sickness or with ARDS, β2AR agonists caused enhanced clearance of alveolar edema (1, 24–26). Formoterol in conjunction with a steroid reduced up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in IL-1β-treated fibroblasts (27). Formoterol also suppressed release of mast cell mediators (such as histamine and leukotrienes) from human lung (28). During ARDS, β2AR agonists may have the following effects on lung inflammatory responses in lung: reduced endothelial permeability and enhanced clearance of alveolar fluid, increased surfactant production, reduced cytokine production, reduced adhesion molecule expression on endothelial cells, and increased mucociliary clearance, all of which would be expected to attenuate the lung inflammatory response (29).

βAR agonists (β1AR, β2AR) may reduce PMN sequestration in the lung following airway delivery of LPS. Pretreatment of mice with the β1AR agonist dobutamine reduced PMN content in BALFs by 30%, together with reduced levels of IL-6, IL-10, and MIP-2α (CXCL2) (30). There is convincing evidence that β2AR agonists cause reductions in ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in human bronchial epithelial cells, resulting in reduced adhesiveness of PMNs to these cells (31–33). Increased levels of cAMP in PMNs exposed to β2AR agonists also resulted in reduced adherence of PMNs to bronchial epithelial cells (32). Human lung fibroblasts exposed to β2AR agonists impaired the ability of IL-1β to up-regulate ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (27). It appears that exposure of endothelial cells to β2AR agonists resulted in reduced paracellular movement across monolayers of endothelial cells of FITC-dextran, together with induction of NO formation (34, 35). Collectively, β2AR agonists seem to have a variety of anti-inflammatory outcomes due to effects on PMNs, lung fibroblasts, bronchial epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. However, the extent to which these responses can be linked to induction of cAMP is not clear. Another response to β2AR agonists that could have anti-inflammatory outcomes is induction of IL-10, which is described in this report, as well as elsewhere (36).

There is little question that β2AR agonists activate adenylate cyclase in bronchial smooth muscle cells, causing generation of cAMP, resulting in smooth muscle relaxation. This is the basis for the use of β2AR agonists in the settings of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in asthma. The extent to which such treatment may reduce the amount of inflammatory cells in the upper airways is unclear. As noted, β2AR agonists suppressed distal airway ALI (edema, fibrin deposition, PMN accumulation, and alveolar hemorrhage; Fig. 5). The mechanisms of such effects appear to be unrelated to effects on cAMP levels (Fig. 3) and may be linked to suppressed production of mediators via inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway of CXC chemokines that activate PMNs (e.g., KC; Fig. 1). In addition, TNF-α levels in BALFs were sharply reduced in the presence of β2AR agonists, as was release of TNF-α and other proinflammatory mediators from LPS-stimulated macrophages (see discussion of Fig. 3 in Results). These studies suggest that β2AR agonists function via a variety of mechanisms to suppress acute inflammatory responses in lung.

One might note that in Fig. 1E, there are some striking differences in inhibitory effects of β2AR agonists on BALF mediators when data with R,R-formoterol are compared to results with S-albuterol. It may be that the two β2AR agonists have different effects on some of the mediator responses because of differences in the way in which formoterol and albuterol bind to β2AR and differences in their modes of action and potency. Formoterol has fast and long-lasting effects and is more potent than albuterol (a short-acting agonist) at the same dosage concentration (37). Further, even when two long-acting β2AR agonists, such as formoterol and salmeterol, were used, their levels of inhibition of TNF-α and GM-CSF release from LPS-treated monocyte derived macrophages were quite different (38). In addition, differences in efficacy were as much as 50%, with formoterol being more effective than salmeterol in suppressing TNF-α release. Therefore, it is not surprising that, although formoterol and albuterol are both β2 agonists, depending on the endpoint (cytokine/chemokine release), these two β2AR agonists may display quite divergent results.

An important question is the intrapulmonary concentration of β2AR agonists. In a report by Atabai et al. (39), ventilated patients with pulmonary edema (hydrostatic, n=10; ALI, n=12) received albuterol delivery via aerosol for 6 h, at which time edema fluid was aspirated, revealing the albuterol level of 10−6 M, which was the concentration of albuterol and formoterol used in the current experimental study. The extent to which β2AR agonists being delivered into lungs of humans by aerosol reduces the intensity of ALI is debatable (see above). Also, the pharmacokinetics of β2AR agonists in lung are poorly understood, raising the question about the duration over which such levels of β2AR agonists can be maintained in human lungs.

Several clinical studies have investigated the efficacy of β2AR agonists in the treatment of ALI/ARDS. A recent retrospective study of 86 mechanically ventilated patients with ALI treated with albuterol (salbutamol) by inhalation (>2.2 mg/d) concluded that there was improvement in survival and reduction in ALI when compared to the use of low-dose albuterol (<2.2 mg/d) (25). In another clinical trial involving 66 patients with ALI, albuterol was infused intravenously, resulting in a significant reduction in lung water, although these patients had a higher incidence of supraventricular arrhythmias (40). In contrast, a recently published fairly large clinical study (randomized phase III trial) with aerosolized albuterol failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy based on mortality, ventilator-free days, blood oxygenation, and plasma levels of IL-6 and IL-8 (on d 1 and 3 during treatment; ref. 41). It seems that it is too early to determine whether discrepancies in the 3 reports are due to differences in design of the studies, or explained by different clinical endpoints, differences in routes of administration of the drugs, or other factors. Clearly, our experimental results indicate that β2AR agonists are effective in confining the tissue-destructive inflammatory response underlying ALI in the experimental setting when these agonists are delivered via the airways during the development of ALI. There is no current information about the protective effects of β2AR agonists if administration is delayed after the onset of ALI. In the clinical setting, early initiation of treatment before the patient requires positive-pressure ventilation (42) may be a critical determinant that could influence the potential beneficial effect of β2AR agonists on the course of clinical lung injury, ALI/ARDS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants to P.A.W. (GM-29507, GM-61656), J.J.G. (NHLBI-T32-HL007517-29), and M.A.M. (HL-51856, HL-51854) and by a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant to M.B. (project 571701, BO 3482/1-1). The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors acknowledge the excellent staff support of Beverly Schumann, Sue Scott, and Robin Kunkel.

Footnotes

- β2AR

- β2 adrenergic receptor

- ALI

- acute lung injury

- ARDS

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BALF

- bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- IgGIC

- IgG immune complex

- IgGIC-ALI

- IgG immune complex–induced acute lung injury

- JNK

- Jun-N-terminal kinase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- LPS-ALI

- lipopolysaccharide-induced aculte lung injury

- MH-S

- SV40-transformed mouse macrophage line

- MLE-12

- mouse lung alveolar epithelial cell line 12

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PEM

- peritoneal exudate (thioglycollate)-induced macrophage

- PMN

- polymorphonuclear neutrophil.

REFERENCES

- 1. Matthay M. A., Zimmerman G. A. (2005) Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 33, 319–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goss C. H., Brower R. G., Hudson L. D., Rubenfeld G. D. (2003) Incidence of acute lung injury in the United States. Crit. Care Med. 31, 1607–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakuma T., Folkesson H. G., Suzuki S., Okaniwa G., Fujimura S., Matthay M. A. (1997) Beta-adrenergic agonist stimulated alveolar fluid clearance in ex vivo human and rat lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155, 506–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sakuma T., Okaniwa G., Nakada T., Nishimura T., Fujimura S., Matthay M. A. (1994) Alveolar fluid clearance in the resected human lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150, 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tracey K. J. (2009) Reflex control of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 418–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flierl M. A., Rittirsch D., Nadeau B. A., Chen A. J., Sarma J. V., Zetoune F. S., McGuire S. R., List R. P., Day D. E., Hoesel L. M., Gao H., Van Rooijen N., Huber-Lang M. S., Neubig R. R., Ward P. A. (2007) Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature 449, 721–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dutta E. J., Li J. T. (2002) Beta-agonists. Med. Clin. North. Am. 86, 991–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sartori C., Allemann Y., Duplain H., Lepori M., Egli M., Lipp E., Hutter D., Turini P., Hugli O., Cook S., Nicod P., Scherrer U. (2002) Salmeterol for the prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1631–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAuley D. F., Frank J. A., Fang X., Matthay M. A. (2004) Clinically relevant concentrations of beta2-adrenergic agonists stimulate maximal cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent airspace fluid clearance and decrease pulmonary edema in experimental acid-induced lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 32, 1470–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen F., Nakamura T., Fujinaga T., Zhang J., Hamakawa H., Omasa M., Sakai H., Hanaoka N., Bando T., Wada H., Fukuse T. (2006) Protective effect of a nebulized beta2-adrenoreceptor agonist in warm ischemic-reperfused rat lungs. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 82, 465–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maris N. A., de Vos A. F., Dessing M. C., Spek C. A., Lutter R., Jansen H. M., van der Zee J. S., Bresser P., van der Poll T. (2005) Antiinflammatory effects of salmeterol after inhalation of lipopolysaccharide by healthy volunteers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 878–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bosmann M., Patel V. R., Russkamp N. F., Pache F., Zetoune F. S., Sarma J. V., Ward P. A. (2011) MyD88-dependent production of IL-17F is modulated by the anaphylatoxin C5a via the Akt signaling pathway. FASEB J. 25, 4222–4232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bosmann M., Russkamp N. F., Patel V. R., Zetoune F. S., Sarma J. V., Ward P. A. (2011) The outcome of polymicrobial sepsis is independent of T and B cells. Shock 36, 396–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rittirsch D., Flierl M. A., Day D. E., Nadeau B. A., McGuire S. R., Hoesel L. M., Ipaktchi K., Zetoune F. S., Sarma J. V., Leng L., Huber-Lang M. S., Neff T. A., Bucala R., Ward P. A. (2008) Acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide is independent of complement activation. J. Immunol. 180, 7664–7672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huber-Lang M., Sarma J. V., Zetoune F. S., Rittirsch D., Neff T. A., McGuire S. R., Lambris J. D., Warner R. L., Flierl M. A., Hoesel L. M., Gebhard F., Younger J. G., Drouin S. M., Wetsel R. A., Ward P. A. (2006) Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat. Med. 12, 682–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao H., Neff T., Ward P. A. (2006) Regulation of lung inflammation in the model of IgG immune-complex injury. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1, 215–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shanley T. P., Schmal H., Warner R. L., Schmid E., Friedl H. P., Ward P. A. (1997) Requirement for C-X-C chemokines (macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant) in IgG immune complex-induced lung injury. J. Immunol. 158, 3439–3448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Warren J. S., Yabroff K. R., Remick D. G., Kunkel S. L., Chensue S. W., Kunkel R. G., Johnson K. J., Ward P. A. (1989) Tumor necrosis factor participates in the pathogenesis of acute immune complex alveolitis in the rat. J. Clin. Invest. 84, 1873–1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bennett B. L., Sasaki D. T., Murray B. W., O'Leary E. C., Sakata S. T., Xu W., Leisten J. C., Motiwala A., Pierce S., Satoh Y., Bhagwat S. S., Manning A. M., Anderson D. W. (2001) SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 13681–13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson M. (1998) The beta-adrenoceptor. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 158, S146–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mutlu G. M., Factor P. (2008) Alveolar epithelial beta2-adrenergic receptors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 38, 127–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fiorentino D. F., Zlotnik A., Mosmann T. R., Howard M., O'Garra A. (1991) IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 147, 3815–3822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whelan C. J., Johnson M., Vardey C. J. (1993) Comparison of the anti-inflammatory properties of formoterol, salbutamol and salmeterol in guinea-pig skin and lung. Br. J. Pharmacol. 110, 613–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matthay M. A., Abraham E. (2006) Beta-adrenergic agonist therapy as a potential treatment for acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173, 254–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manocha S., Gordon A. C., Salehifar E., Groshaus H., Walley K. R., Russell J. A. (2006) Inhaled beta-2 agonist salbutamol and acute lung injury: an association with improvement in acute lung injury. Crit. Care 10, R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mutlu G. M., Sznajder J. I. (2005) Mechanisms of pulmonary edema clearance. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 289, L685–L695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spoelstra F. M., Postma D. S., Hovenga H., Noordhoek J. A., Kauffman H. F. (2002) Additive anti-inflammatory effect of formoterol and budesonide on human lung fibroblasts. Thorax 57, 237–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scola A. M., Loxham M., Charlton S. J., Peachell P. T. (2009) The long-acting beta-adrenoceptor agonist, indacaterol, inhibits IgE-dependent responses of human lung mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 158, 267–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perkins G. D., McAuley D. F., Richter A., Thickett D. R., Gao F. (2004) Bench-to-bedside review: beta2-agonists and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care 8, 25–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dhingra V. K., Uusaro A., Holmes C. L., Walley K. R. (2001) Attenuation of lung inflammation by adrenergic agonists in murine acute lung injury. Anesthesiology 95, 947–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oddera S., Silvestri M., Lantero S., Sacco O., Rossi G. A. (1998) Downregulation of the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 on bronchial epithelial cells by fenoterol, a beta2-adrenoceptor agonist. J. Asthma 35, 401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bloemen P. G., van den Tweel M. C., Henricks P. A., Engels F., Kester M. H., van de Loo P. G., Blomjous F. J., Nijkamp F. P. (1997) Increased cAMP levels in stimulated neutrophils inhibit their adhesion to human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Physiol. 272, L580–L587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sabatini F., Silvestri M., Sale R., Serpero L., Di Blasi P., Rossi G. A. (2003) Cytokine release and adhesion molecule expression by stimulated human bronchial epithelial cells are downregulated by salmeterol. Respir. Med. 97, 1052–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Queen L. R., Ji Y., Xu B., Young L., Yao K., Wyatt A. W., Rowlands D. J., Siow R. C., Mann G. E., Ferro A. (2006) Mechanisms underlying beta2-adrenoceptor-mediated nitric oxide generation by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Physiol. 576, 585–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zink S., Rosen P., Lemoine H. (1995) Micro- and macrovascular endothelial cells in beta-adrenergic regulation of transendothelial permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 269, C1209–C1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cobelens P. M., Kavelaars A., Vroon A., Ringeling M., van der Zee R., van Eden W., Heijnen C. J. (2002) The beta 2-adrenergic agonist salbutamol potentiates oral induction of tolerance, suppressing adjuvant arthritis and antigen-specific immunity. J. Immunol. 169, 5028–5035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roux F. J., Grandordy B., Douglas J. S. (1996) Functional and binding characteristics of long-acting beta 2-agonists in lung and heart. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 153, 1489–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Donnelly L. E., Tudhope S. J., Fenwick P. S., Barnes P. J. (2010) Effects of formoterol and salmeterol on cytokine release from monocyte-derived macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 36, 178–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Atabai K., Ware L. B., Snider M. E., Koch P., Daniel B., Nuckton T. J., Matthay M. A. (2002) Aerosolized beta(2)-adrenergic agonists achieve therapeutic levels in the pulmonary edema fluid of ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 28, 705–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perkins G. D., McAuley D. F., Thickett D. R., Gao F. (2006) The beta-agonist lung injury trial (BALTI): a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173, 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matthay M. A., Brower R. G., Carson S., Douglas I. S., Eisner M., Hite D., Holets S., Kallet R. H., Liu K. D., MacIntyre N., Moss M., Schoenfeld D., Steingrub J., Thompson B. T. (2011) Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized beta-agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 561–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levitt J. E., Bedi H., Calfee C. S., Gould M. K., Matthay M. A. (2009) Identification of early acute lung injury at initial evaluation in an acute care setting prior to the onset of respiratory failure. Chest 135, 936–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]