Abstract

Background & objectives:

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is used frequently in developing countries, but investigations of patients’ awareness and perception of ECT are rare. The present study thus attempted a comprehensive examination of knowledge, experience and attitudes concerning ECT among patients treated with brief-pulse, bilateral, modified ECT, and their relatives.

Methods:

Of the 153 recipients of ECT, 77 patients and relatives were eventually assessed using questionnaires designed to evaluate their awareness and views about ECT.

Results:

Patients were middle-aged, poorly-educated, often unemployed, with chronic, severe, and predominantly psychotic illnesses. Relatives were mainly parents, older, better-educated and usually employed. Apart from the very rudimentary aspects, patients were largely unaware of the procedure. Though most did not find the experience of ECT upsetting, sizeable proportions expressed dissatisfaction with aspects such as informed consent, fear of treatment and memory impairment. Although patients were mostly positive about ECT, ambivalent attitudes were also common, but clearly negative views were rare. Relatives were significantly likely to be more aware, more satisfied with the experience and have more favourable attitudes towards ECT, than patients.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The results endorse the notion that recipients of ECT are generally well-disposed towards the treatment, but also indicate areas where practice of ECT needs to be improved to enhance satisfaction among patients and relatives.

Keywords: Awareness, ECT, patients, perceptions, relatives

Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective, safe and widely practiced treatment, it has also been one of most controversial and misunderstood procedures1–3. Unfortunately, in the ongoing debate about the merits and demerits of the treatment, the opinions of patients who have undergone ECT and their relatives have rarely been sought. Clinicians and researchers have traditionally focused on aspects such as efficacy, side effects and mechanism of action. However, the realisation that mere clinical efficacy of ECT did not necessarily predict patients’ perceptions or satisfaction with the treatment has eventually led to several investigations of the knowledge, attitudes and experience of the procedure among patients4,5. Despite this, research on awareness and perceptions of ECT among its recipients and their families from developing countries is scarce6. ECT is used quite frequently in many of these countries, but improper and unregulated use is also very common7–10. Whether this adversely affects attitudes towards ECT is still to be properly assessed. Moreover, differences in socio-cultural milieus of developing countries can influence attitudes towards ECT; this is yet to be ascertained8. More recently, there has been growing public concern about ECT even in developing countries like India11. Issues such as the need for the treatment and for unmodified ECT are being frequently debated. In such a climate, examination of the views of patients and relatives about ECT could help in determining the role of this treatment more precisely.

We therefore, undertook this study which attempted to comprehensively examine knowledge, attitude and experience regarding ECT, of patients who had undergone the treatment and their relatives.

Material & Methods

The study was carried out at the department of psychiatry of a tertiary-care multi-speciality hospital (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh) catering to a major part of north-India. The psychiatry department has outpatient facilities and a general psychiatry inpatient unit with 24 beds. About 5500 new patients are seen annually and about 200 patients are admitted to the inpatient unit each year. About 50 patients receive ECT each year.

This was a cross-sectional study of all patients who had received ECT in a three-year period from January 2006 - December 2008. d0 ata collection was carried out between January 2007 and February 2009. The ECT register of the department was screened to identify all patients who had received ECT from 2006 to 2008. Suitable patients, living with their families, were contacted either in person, or by telephone/letters. The study was explained during this contact and patients were invited to participate with their relatives. Demographic and treatment details of ‘non-participants,’ who could not be contacted despite best efforts, were recorded. Only those patients who were in remission, were included; remission defined as Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores of less than 7; Young Mania Rating Scale scores of less than 6; and scores of 3 or less on psychotic symptoms of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Patients with organic brain syndrome were excluded. Relatives were healthy adults selected from those who were actively involved in giving consent for, and looking after the patient during ECT. Though the sample size could not be determined a priori, the target for the current study was intended to be in the range of 50 to 100 participants as done in earlier studies.

The study protocol was approved by the Institute Research and Ethics Committees. Participants were inducted only after they had given written informed consent. Other ethical safeguards were also maintained12.

Assessments: Demographic and clinical details were obtained from the participants and treatment records. Psychopathology was assessed using appropriate scales.

Attitude, knowledge and experience questionnaires: These were designed specifically for the present study. Items included were generated from several previous studies on the subject8,13–17. Detailed descriptions of items allowed the questionnaires to be used in a semi-structured interview format. Preliminary versions were prepared for both patients and relatives. These were initially applied to a random group of 20 patients and their relatives, who were not included in the main study. Changes made during this testing were subsequently incorporated in the versions finally used. The final versions of the questionnaires were essentially similar to the original one used by Freeman and Kendell13 and also to the version modified by Tang et al8, which has been used subsequently in other studies from developing countries16,17. Apart from the pilot survey carried out as a part of this study, versions of the same questionnaires were simultaneously validated among a large population of caregivers from the same centre18.

All assessments were carried out a minimum of two weeks after the last ECT. Assessors were not involved in treatment of the patients included.

Administration of ECT: ECT is administered in the department to both inpatients and outpatients. The consultant-in-charge of the patient makes the final decision about administering ECT after discussion with members of the treatment team. In complicated cases, a second opinion is usually sought from other consultants. The decision to administer ECT is taken individually in each patient, based on a review of his or her clinical status and previous treatment history. Once the treating-team decides ECT is clinically indicated, written informed consent is sought from both patients and their relatives, after detailed explanation of the process, need for treatment and possible effects. ECT is administered only on a voluntary basis; i.e., only when both patients and relatives provide fully informed consent. Consenting patients undergo physical assessment and investigations as required and are also assessed by the anaesthetist. If found fit, the patient is administered brief-pulse, bilateral, modified ECT, 2-3 times a week, with proper monitoring of vital signs, of seizure parameters, and of the status during the post-ECT period. Relatives of patients are actively involved throughout the whole process of treatment including assessment, consent, administration and post-ECT care.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistics consisted of frequency counts, percentages, means and standard deviations. Chi-square tests were used for comparisons.

Results

One hundred and fifty three patients had received ECT during the study period, including 55 patients each in 2006 and 2007 and 43 patients in 2008. This amounted to about a quarter of all the inpatient admissions (n = 629) during this period. Four patients who had died, were institutionalized, or had organic brain syndrome were excluded. Of the 149 eligible patients, 65 responded to the first contact and 12 to the second contact. The final sample thus included 77 patient-relative pairs, 20 from 2006, 37 from 2007 and 20 from 2008. Seventy six patients could not be contacted and constituted the ‘non-participant’ group.

Participants and non-participants were compared on demographic parameters (age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, family type and residence), illness variables (age of onset, primary and co-morbid diagnoses), and characteristics of the index episode of treatment with ECT (age, duration, primary and co-morbid diagnoses). The only significant difference that emerged was the significantly lower number of participants with more than 10 years of education (P<0.01).

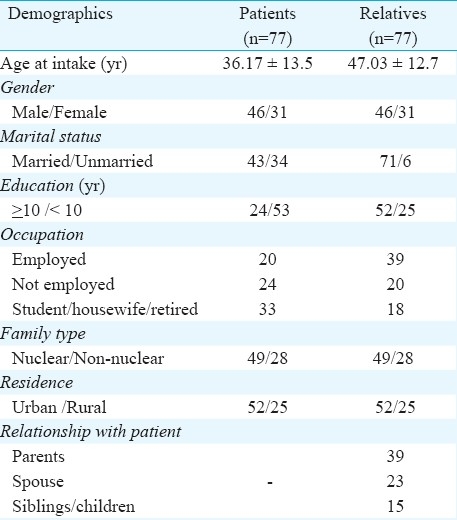

Profile of the study subjects: The study-sample consisted of middle-aged patients, slightly more men than women. Presumably because of their chronic and severe illnesses most patients were not well-educated; a little less than half (44%) were unmarried, and about a third (32%) were unemployed. Relatives were mostly parents of patients; hence, usually much older, married, well-educated and employed (Table I). In developing countries ECT is more often used as an adjunctive treatment for those with psychosis, than for patients with depression. Though patients with psychoses in this study outnumbered those with depressive or bipolar disorders, the index treatment-episode was more often one of severe depression (with/without psychosis), followed by psychotic exacerbations and mania with psychotic symptoms. A high proportion of patients (77%) thus had psychotic symptoms while receiving ECT.

Table I.

Demographic profile of study-participants

All patients were receiving concomitant psychotropics.

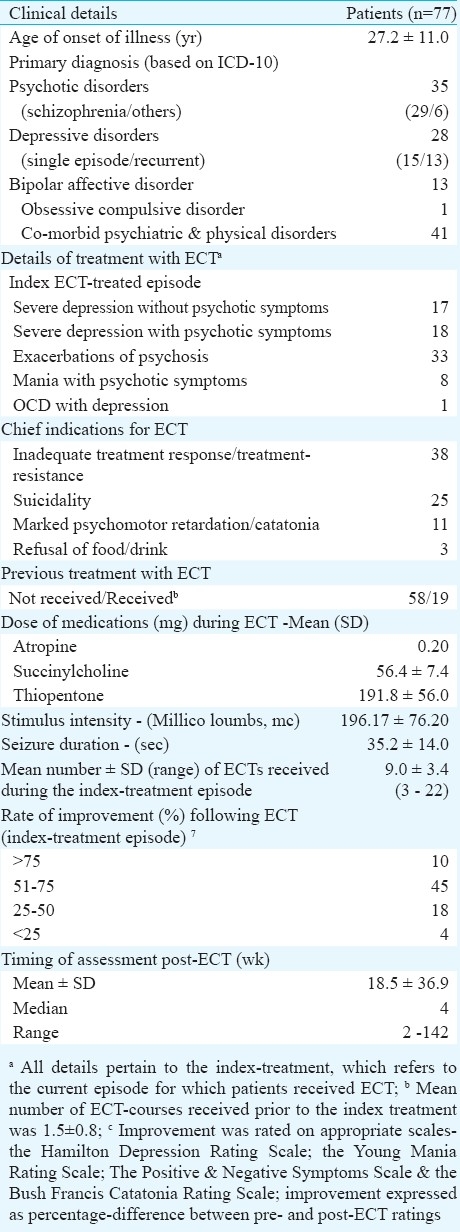

The average patient was assessed 18.5 wk after the last ECT (SD- 36.9; median - 4 wk; range - 2-142 wk) (Table II). The majority were assessed 2 - 4 wk post-ECT (62%), followed by 5-24 wk (22%). A minority were evaluated 25-48 wk post-ECT (9%), and beyond 48 wk post-ECT (9%).

Table II.

Clinical and treatment profile of patients

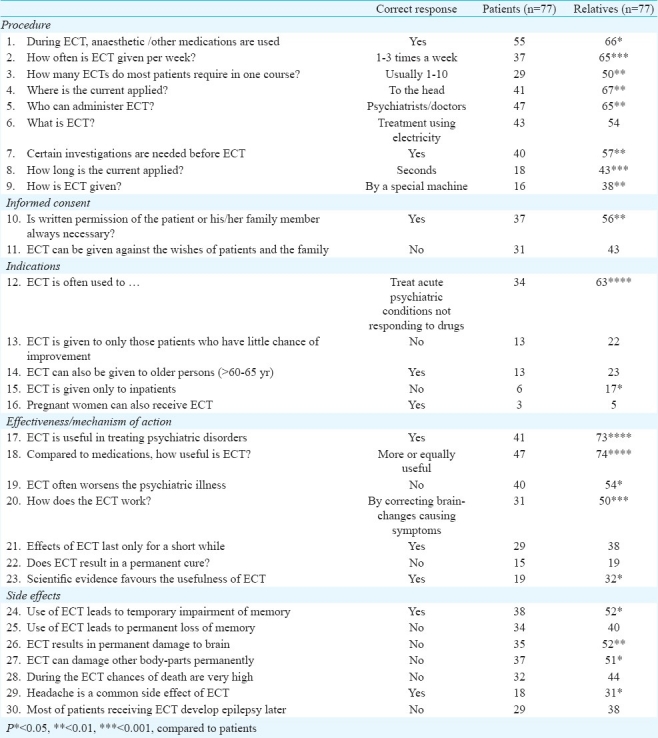

Knowledge of ECT: Knowledge was assessed using a 30-item questionnaire. Each item had a correct, an incorrect and a ‘don’t know’ response. Incorrect and ‘don’t know’ responses were clubbed together, because both signified that the participant was unaware. Additionally, participants were also asked to name the sources from which they derived their information about ECT.

The principal source of information for both patients (57%) and relatives (87%) was the treating doctor. About a fifth of the patients (18%) had learnt from their own previous experience, while about a third of the relatives (35%) had learnt about ECT from others. Relatives were thus significantly more likely than patients, to have acquired their facts from doctors, or other people (P<0.001). The media was a less common source for both patients (12%) and relatives (19%).

None of the patients could answer all the questions correctly; only a minority (12,16%) came close to getting all their facts right. The majority (40-55, 52-71%) were only aware of the rudiments of the procedure. Fewer patients (29-38, 38-49%) knew about the more specific aspects of the procedure, the consent process, mechanism, usual indications and side effects. Only a small proportion (3-19, 4-25%) was aware of all possible indications and other finer details. In direct contrast, a greater proportion of relatives (40-74, 52-96%) were well aware about several aspects of ECT; differences in this regard between relatives and patients were often significant. However, even among relatives, few (5-38, 6-49%) knew the intricate details (Table III).

Table III.

Knowledge of ECT among patients and their relatives

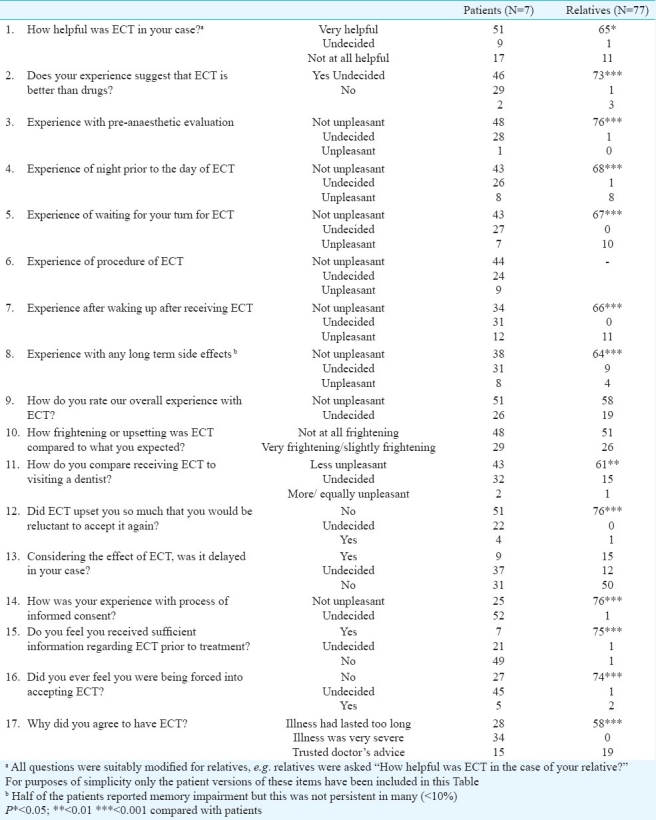

Experience of ECT: Experience of ECT among patients was assessed using a 16-item questionnaire (15 items for relatives). Possible responses either denoted a positive experience, a negative one or an uncertain view. An additional item related to reasons for consenting to ECT.

Most patients (34, 44%) agreed to have ECT because of their prolonged illness, some (28, 36%) because of its severity or non-response, and fewer (15, 20%) because they trusted their doctors. Conversely, a significantly (P<0.001) larger majority of the relatives (58, 75%) consented because of severity/non-response of the illness, the rest because of their trust in doctors. A majority of the patients (46-51, 60-66%) were convinced of the benefits of ECT and did not find the experience frightening or upsetting (43-51, 56-66%). Consequently, most (51, 66%) were willing to repeat the treatment. However, many were unhappy about aspects such as information received prior to treatment (49, 64%), delayed treatment, fear of treatment, and other ill-effects of ECT (17-31, 22-40%). A sizeable section of the patients (21-37, 27-48%) were hesitant in evaluating their experience of almost all aspects of the treatment, particularly regarding their experience of the consent process (45-52, 58-68%). Unlike patients, a significantly larger proportion of the relatives (66-99%), compared to patients, judged different aspects of the experience more positively. However, many relatives were also upset by delayed treatment (50, 65%), some by the fear provoked by ECT (26, 34%), and many had mixed feelings about other aspects (9-19, 12-25%). (Table IV).

Table IV.

Experience with ECT among patients and their relatives

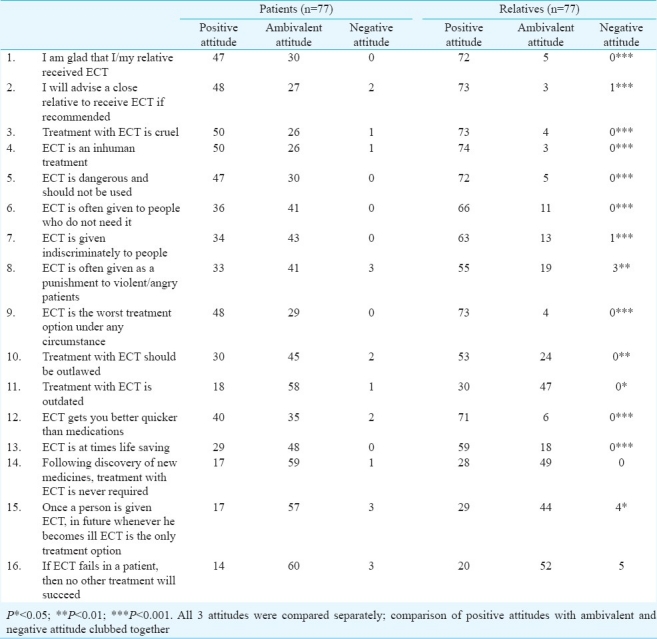

Attitudes towards ECT: These were assessed using a 16-item questionnaire. Each item had 3 alternatives based on which responses were categorised into positive, negative or ambivalent attitudes.

A large member of patients (40-50, 52-65%) held positive attitudes on 7 of the 16 items. Accordingly, a majority of the patients were happy to have received ECT and endorsed its use because they felt it was not cruel, inhuman, dangerous, or the worst option for treatment. Simultaneously, 26-60 patients (34-78%) expressed ambivalent attitudes about all aspects of ECT, particularly regarding the indiscriminate/punitive use of ECT and the relevance of the treatment. However, despite such ambivalence, only a small proportion of the patients (0-3, 0-4%) had clearly negative attitudes (Table V). A much larger and significant (P<0.5-0.0001) proportion of the relatives (53-74, 69-96%) had clearly positive attitudes on 12 of the 16 items. But even among relatives, many (11-52, 14-68%) were unsure about several aspects of the treatment, though very few (0-5, 0-6%) expressed clearly negative views.

Table V.

Attitudes towards ECT among patients and their relatives

Comparisons of patients from 2006 (n = 20) with those from 2007 and 2008 (n = 57) revealed significant differences on 27 of the total of 62 items. In almost all instances the differences favoured patients who had received ECT in 2006, who were more aware and positive about ECT. However, this trend was not found among the relatives (data not shown).

Discussion

Perceptions and awareness regarding ECT among patients and their relatives could have a significant impact on the outcome of the treatment. However, these have been rarely examined in the Indian context.

Most patients in this study obtained their information about ECT from doctors, past experience or other recipients. This is not unusual among patients who have undergone ECT in countries where it is used frequently. Patients from countries with less frequent use are more likely to acquire their facts from the media19, and usually have more negative perceptions of ECT20.

Despite this, patients of this study were poorly informed about ECT. A majority of patients were unaware of anything more than the rudiments of the procedure; very few were familiar with most other aspects. These results mirror the dominant trend in literature, which suggests that patients who receive ECT often know little about what it exactly involves21. Some other studies from India14,15 had earlier reported that a high proportion of patients (>65%) had adequate knowledge of ECT. However, on closer scrutiny the proportion of patients with full understanding of the treatment, particularly about placement of electrodes, duration of stimulus or fits, side effects and indications, was actually much lower (6-17%) in these studies.

Poor information about ECT could be partly due to ECT-induced memory impairment (present in about half of the patients of this study) or confounding effects of current mental state21. Alternatively, it could be due to inadequate information offered prior to ECT. Systematic review on this aspect has concluded that only about half of the patients are satisfied by amount of information they receive prior to ECT22. In this study, the proportion of patients who felt that they had not received sufficient information regarding ECT prior to treatment was higher than that reported in previous studies from India and other developing countries8,17,23–25.

Favourable opinions about patients’ experience are quite common in literature21. However, fear of ECT and concern about side effects and dissatisfaction with consent procedures are also reported. In our study unawareness and discontentment with consent procedures as well as feelings of coercion, indicated deficiencies in the process of informed consent, similar to that reported ealier22, particularly from developing countries8,17,25 including India7,23,24. Although, the realities of the situation may make for somewhat different norms and standards of consent in developing countries, such shortcomings of the consent process are of great concern. About half of the patients complained of memory impairment, which they found distressing. Memory impairment is usually the commonest side effect reported in virtually all studies of ECT recipients. Rates vary from 29 to 79 per cent of the patients, with persistent loss being reported by at least one-third of them26.

In this study about two-thirds of the patients felt that they had benefited from ECT and were willing to repeat it again. These results were similar to those of conventional research from clinical settings in developing as well as developed countries, which has shown that a majority of the patients perceive ECT to be helpful and most are willing to undergo the treatment again21. But, despite rating ECT so high, many patients of this study often chose to remain ambivalent in their attitudes, although very few were frankly critical of the treatment. This ambivalence could be interpreted in several different ways. Disturbed mood state often leads to negative perceptions of ECT27, but was unlikely to be a major factor in this study, since all patients were either euthymic or free from psychotic symptoms, when assessed. Attitudes are often not simple for or against decisions; instead these represent a complex trade-off between judgements of benefits and risks. Thus, as in this study, ambivalence might be the norm, rather than the exception13,26. However, patients’ reluctance to reveal their true attitudes to the doctors who treat them, has generated the maximum debate13,28. This notion is further endorsed by several surveys of ECT undertaken by consumer-organizations (using methods different from clinical research), which either report much lower rates of perceived benefit, or more widespread criticism of ECT among respondents5,26,29.

One of the strengths of the study was inclusion of relatives. Results in this regard were somewhat remarkable in that relatives were much better off than patients in almost every respect. Accordingly, they had better access to diverse sources of information, were more aware of several details concerning ECT, were more likely to be satisfied with different parts of the consent process including information offered prior to treatment, and less likely to perceive coercion. They found the experience of ECT much less disagreeable, reported greater benefit and willingness to accept the treatment again, and also were much more positive regarding ECT. Such a trend favouring relatives has been a consistent finding among studies from developing countries8,17,24, but has not usually been found in Western studies6. The fact that relatives neither suffered from the ill effects of the illness, nor had to endure the experience of ECT or its adverse effects, might have contributed to their better awareness and more positive perceptions. The influence of other variables was uncertain, though relatives with higher levels of education had more positive attitudes about ECT.

The present study suffered from some of the usual methodological limitations. Although the sample size compared well with most other studies on the subject, it can be argued that the number of participants was still relatively small, and the sample was diagnostically heterogeneous. The fact that half of the recipients could not be assessed raises doubts about the representativeness of the sample. However, comparisons between participants and non-participants did not reveal major differences in any respect. Moreover, the demographic and clinical profiles of patients were typical of recipients of ECT in India and other developing countries7–10. Also, marked variations in practice of ECT in India7,10 mean that the results cannot be readily applied to other patients. Thus, the findings might not be truly representative of the awareness and perceptions of all ECT recipients and their relatives in this country. The possibility of a positive bias to the results arising from patients being in remission was unlikely, because the remission rates were not significantly different from other Indian studies30,31. Further, the characteristic response among patients was of ambivalence regarding ECT, rather than unequivocal endorsement of the treatment. Every attempt was made to ensure the validity of the questionnaires by using standardised formats13, by relying on versions used in studies from developing countries8,16,17, by carrying out a pilot survey prior to the study, and by simultaneous use among a large group of caregivers from the same site18. Still, concerns about validity remain, especially when the whole approach of assessing attitudes in this fashion has drawn some criticism26,32. The timing of the assessments is also critical. However, the average ECT-assessment interval of 18.5 wk achieved in this study appeared to be in line with previous recommendations26.

Despite these difficulties, the results of this study were similar to much of the previous data on the subject, both from developing and developed countries. It highlights the areas where the practice of ECT needs to be improved, particularly in developing countries like India. In this regard, recent evidence from accredited ECT clinics in developed countries clearly demonstrates that the stress and dis-comfort associated with the procedure can be con-siderably lessened by adhering to certain minimum standards of care29,30,33,34. It should not be difficult to imple-ment these standards, which emphasise reduced waiting times, provision of clean and comfortable environments, practical and emotional support by dedicated staff, and close involvement of families of patients. However, adherence to these minimum standards of care will certainly have a positive impact on the perceptions of patients and relatives about ECT, thereby ensuring better access to the treatment for those who are most likely to benefit form it.

References

- 1.Carney S, Geddes J. Electroconvulsive therapy. Br Med J. 2003;326:1343–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman JA, Krahn LE, Smith GE, Rummans TA, Pileggi TS. Patient satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:967–71. doi: 10.4065/74.10.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowman J, Patel A, Rajput K. Electroconvulsive therapy: attitudes and misconceptions. J ECT. 2005;21:84–7. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000161043.00911.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malcolm K. Patient's perceptions and knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Bull. 1989;13:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnstone L. Adverse psychological effects of ECT. J Mental Health. 1999;8:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakrabarti S, Grover S, Rajagopal R. Perceptions and awareness of electroconvulsive therapy among patients and their families: A review of the research from developing countries. J ECT. 2010;26:317–22. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e3181cfc8ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal AK, Andrade C, Reddy MV. The practice of ECT in India: issues relating to the administration of ECT. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:285–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang WK, Ungvari GS, Chan GWL. Patients’ and their relatives’ knowledge of, experience with, attitude toward, and satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy in Hong Kong, China. J ECT. 2002;18:207–12. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little JD. ECT in the Asia Pacific region: what do we know? J ECT. 2003;19:93–7. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chanpattana W, Kunigiri G, Kramer BA, Gangadhar BN. Survey of the practice of electroconvulsive therapy in teaching hospitals in India. J ECT. 2005;21:100–4. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000166634.73555.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathare S. Beyond ECT: priorities in mental health care in India. Indian J Med Ethics. 2003;11:11–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants. New Delhi: ICMR; 2006. Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman CPL, Kendell RE. ECT: Patients’ experiences and attitudes. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:8–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandra B, Gangadhar BN, Lalitha N, Janakiramaiaiah N, Shivananda BS. Patients’ knowledge about ECT. NIMHANS J. 1992;10:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavan BS, Kumar S, Arun P, Kumar S, Bala C, Singh T. ECT: Knowledge and attitude among patient and their relatives. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:34–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virit O, Ayar D, Savas HS, Yumru M, Selek S. Patients’ and their relatives’ attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar disorder. J ECT. 2007;23:255–9. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e318156b77f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malekian A, Amini Z, Maracy MR, Barekatain M. Knowledge of attitude toward experience and satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy in a sample of Iranian patients. J ECT. 2009;25:106–12. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31818050dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Rajagopal R, Khehra N. Does the experience of electroconvulsive therapy improve awareness and perceptions of treatment among relatives of patients? J ECT. 2011;27:67–72. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181d773eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bustin J, Rapoport MJ, Krishna M, Matusevich D, Carlos Finkelsztein C, Strejilevich S, et al. Are patients’ attitudes towards and knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy transcultural? A multi-national pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:497–503. doi: 10.1002/gps.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr RA, McGrath JJ, O’Kearney TO, Price J. ECT: misconceptions and attitudes. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1982;16:43–9. doi: 10.3109/00048678209159469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakrabarti S, Grover S, Rajagopal R. Electroconvulsive therapy: A review of knowledge, experience and attitudes of patients concerning the treatment. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:525–37. doi: 10.3109/15622970903559925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose DS, Wykes HT, Bindman JP, Fleischmann PS. Information, consent and perceived coercion: patients’ perspectives on electroconvulsive therapy. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:54–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vergese MM, Gupta MN, Prabhu GG. The attitude of the psychiatric patient towards electroconvulsive therapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 1968;10:190–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajkumar AP, Saravanan B, Jacob KS. Perspectives of patients and relatives about electroconvulsive therapy: a qualitative study from Vellore, India. J ECT. 2006;22:253–8. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000244237.79672.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arshad M, Arham AZ, Arif M, Bano M, Bashir A, Bokutz M, et al. Awareness and perceptions of electroconvulsive therapy among psychiatric patients: a cross-sectional survey from teaching hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:27–33. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose D, Fleischmann P, Wykes T, Leese M, Bindman J. Patients’ perspectives on electroconvulsive therapy: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326:1363–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers DH. A questionnaire study of patients’ experience of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2007;23:169–74. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e318093eecb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sienaert P, Becker TD, Vansteelandt K, Demyttenaere K, Peuskens J. Patient satisfaction after electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2005;21:227–31. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000183268.62735.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philpot M, Collins C, Trivedi P, Treloar A, Gallacher S, Rose D. Eliciting users’ views of ECT in two mental health trusts with a user-designed questionnaire. J Ment Health. 2004;13:403–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shukla GD. Electroconvulsive therapy in a rural teaching general hospital in India. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:569–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.6.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain G, Kumar V, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in the elderly: a study from the psychiatric unit of a north Indian teaching hospital. J ECT. 2008;24:122–7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318160d61e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose D, Fleischmann P, Wykes T. Consumers’ views of electroconvulsive therapy: a qualitative analysis. J Ment Health. 2004;13:285–93. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kershaw K, Rayner R, Chaplin R. Patients’ views on the quality of care when receiving electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Bull. 2007;31:414–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rush G, Mccarron S, Lucey JV. Patient attitudes to electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Bull. 2007;31:212–4. [Google Scholar]