Abstract

Background & objectives:

Studies on cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in India have shown about 10-20 per cent of cases with no obvious risk factors, raising a suspicion of infections as a cause. There is a paucity of data on this possible role of infections. This study was, therefore, undertaken to find out the association between infection due to Chlamydia pneumoniae and other organisms and coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods:

Patients with CAD were selected in group I (acute myocardial infarction, AMI) and group III (patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery), and normal controls in group II. Routine biochemical, haematological and inflammatory tests [C-reactive protein (CRP), total leucocyte count (TLC), fibrinogen, ESR], serodiagnostic tests for IgA and IgG antibodies to C. pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Parvovirus B-19 by ELISA kits, C. pneumoniae antigen by microimmunofluorescence and PCR from endothelial tissue obtained at CABG were carried out. Aortic punch biopsies were done in patients who underwent CABG.

Results:

Acute MI patients had a significantly higher association with accepted cardiac risk factors, lipid profile, inflammatory and thrombogenic tests. IgG and IgA antibodies levels against C. pneumoniae were not significantly different in the controls as against the AMI group. However, C. pneumoniae antigen seropositive group had significant association with HDL cholesterol, lipid tetrad index (P<0.001) and with triglycerides. Parvovirus B antigen was detected in 8.3 per cent of tissue specimens by PCR and of 44 patients with AMI (6.8%) were also positive for parvovirus B-19 IgG antibodies.

Interpretation & conclusions:

There was no direct evidence of the involvement of C. pneumoniae and other infective agents and viruses in CAD. It is possible that such infections produce an indirect adverse effect on the lipid profile.

Keywords: Chlamydia pneumoniae, chronic infections, coronary artery disease

Worldwide, WHO has estimated in 2005 that out of 17 million deaths, 2/3 occurs in low and medium income countries including India1,2. Deaths in India are due to heart disease in 29 per cent and there has been a 7-fold increase in 4 decades (1960-2000) of the prevalence of IHD in epidemiological studies3. Risk factors have been the subject of many studies, dominated by hypertension, diabetes and smoking with multiple risk factors being in the majority3. However, in 10-20 per cent of cases, there is no obvious risk factor apart from the traditional and newer risk factors3.

Infection has been suspected as a probable cause because of raised total leucocyte count (TLC), C-reactive protein (CRP), ESR and fibrinogen levels, in the acute coronary syndrome4. There have been several studies in industrialized countries5–9 linking infection with coronary artery disease (CAD). Ieren et al10 have shown the results for and against the assumption of infection. There have been four studies conducted in India in the recent past in this area11–14.

We carried out this study to determine the relationship, if any of infections with suspected infective agents e.g. Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Helicobactor pylori, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and parvovirus B-19 with coronary artery disease (CAD) among Indians.

Material & Methods

This study was carried out at National Heart Insitute (NHI) of the All India Heart Foundation (AIHF), New Delhi, between 2000-2004. The Scientific Advisory Research & Ethics Committee of the All India Heart Foundation/National Heart Institute (NHI), New Delhi cleared the proposal. Written consent was taken from all the patients.

Selection of subjects: Consecutive patients with CAD attending outpatient department of NHI during the study period were selected for the study.

-

(1)

Patients of unequivocal acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (Group I, N=200). These were the most likely subjects to show infection, if any.

-

(2)

Normal controls (Group II, N=200). These were age matched controls selected from the Executive Check-up Wellness Programme of the NHI.

-

(3)

Patients subjected to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (Group III, N=168)). These were proven cases of CAD (Table I). At the time of surgery, aortic tissue was obtained and evidence of infection was looked for. Only 168 subjects could be included in this group though originally planned to include 200. Aorta punch biopsies could be obtained only in 70 patients.

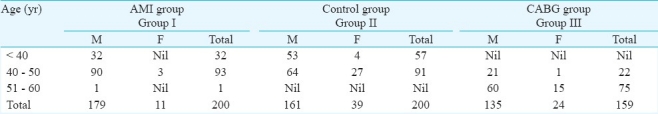

Table I.

Age/sex distribution of patients and control groups

A special proforma was designed to record the clinical history of all subjects. Essential biochemical tests [glucose, lipid profile, kidney & liver function and inflammatory tests (total leucocyte count, TLC, C-reactive protein, CRP and fibrinogen)] were performed in the biochemistry laboratory of the National Heart Institute.

Serological evidence of chronic infection (IgG, IgA) was obtained by using standard test kits available commercially. ELISA(Savyon Diagnostic, Israel; Vircell SL., Spain; Pathozme, UK; Vir-Immun-Labor Diagnostika, Germany; Virion/Serion ELISA Classic, Germany; RIDASCREEN-Biopharm, Germany; Eurogenetics, Belgium), microimmunofluorescence (Vircell SL., Spain), direct immunofluorescence (Dako, Imagen, Denmark), latex agglutination (Ranbaxy, India)]. C . pneumonia antigen was also determined by fluorescent antibody test in 18 of 70 aortic biopsies tested. Eight of the 18 tissue biopsies were tested for antigen by DFA and because of negative results by PCR. PCR and DFA were carried out at the Chalmydia Reference Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi and immunoflorescence at the NHI, New Delhi.

The aortic endothelial tissues were collected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for immunofluorescence from patients undergoing CABG surgery and stored at – 70° C till further testing11. The slide was mounted with the mounting fluid and viewed under the fluorescent microscope (Nikon Corp., Japan) using 490 nm filters for the detection of the C. pneumoniae antigen. The positive and negative controls supplied with the kit were stained simultaneously. Multiple polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies were also carried out on endothelial biopsies for C. pneumoniae, CMV, Enteroviruses and Parvo B-19.

Statistical analysis: Univariate analysis was carried out to estimate the odds ratio and comparison between A ml0 patients and controls using SPSS Software System . T test was used for comparison? between the groups. Multiple logistic regressions by unconditional – conditional method was done to compare titres of C. pneumoniae antibodies in patients and controls at 95 per cent confidence interval.

Results

Maximum number of patients and controls were in the 40-50 yr age group. Male predominance was noted in all three groups (Table I).

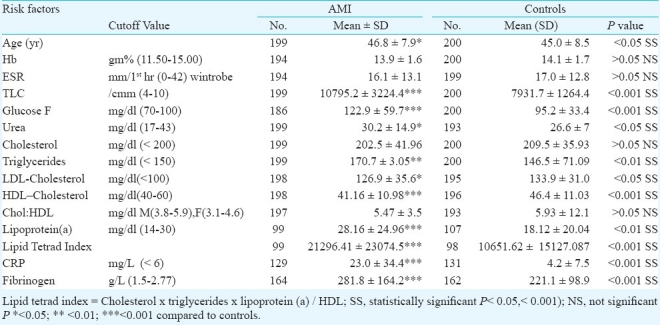

Comparison of the lipid profile in AMI patients (group I) and controls (group II) showed a significant difference (P<0.001) in HDL cholesterol (< 35 mg/dl), and Lipid Tetrad Index, triglycerides level (P<0.01) and lipoprotein (a) (P< 0.05) (Table II).

Table II.

Risk factors in AMI patients and controls

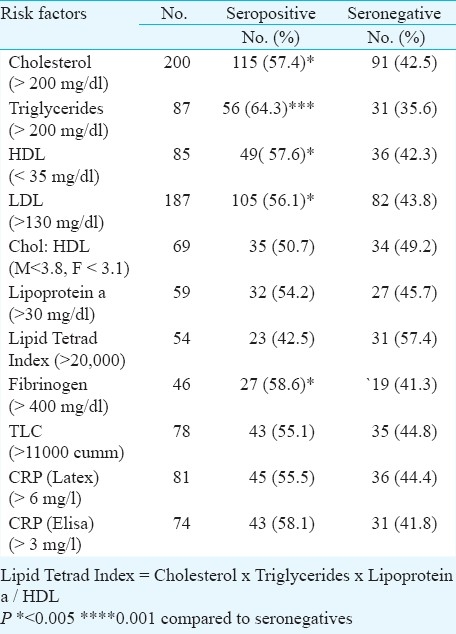

Among the known cardiac risk factors triglycerides were found to be significantly (P<0.001) higher in C. pneumoniae seropositive compared to seronegatives. Low LDL and higher levels of HDL and total cholesterol levels were also seen (P<0.05) in C. pneumoniae seropositive group compared to seronegative group (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison of some known cardiac risk factors with C. pneumoniae seropositivitly

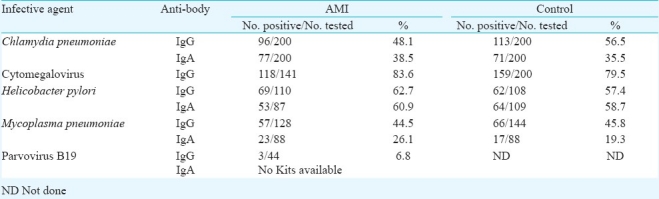

There was no significant difference between the patients and controls with regard to IgG and IgA antibodies with any of the infective agents. Only 6.8 per cent AMI patients showed Parvovirus B antibodies (IgG), no kits were available for IgA (Table IV).

Table IV.

IgG/IgA antibodies in AMI patients and controls to some chronic infective agents

A follow up of eight patients where repeated samples were tested after 6 months to 2 years, no change in C. pneumoniae IgG, IgA antibody titres was observed. These antibodies persisted for a long time perhaps due to the presence of the C. pneumoniae in the tissues leading to chronic active infection.

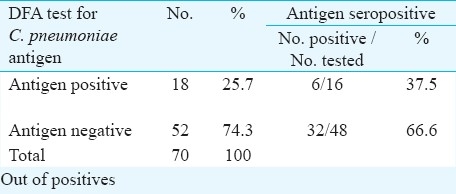

C. pneumoniae antigen was also detected by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test in 18 of 70 (25.7%) aortic tissue biopsies tested (Table V). However, no association was seen between antigen detection and seropositivity. Eight of the 18 tissue biopsies positive for antigen by DFA gave negative results by PCR. By PCR, Parvovirus B was detected in 8 of 98 (8.1%) aortic tissues tested.

Table V.

Association of C. pneumoniae antigen in aortic endothelial tissue biopsies and antibodies to C. pneumoniae

Discussion

In the present study, no significant difference in C. pneumoniae IgA and IgG levels was seen in the two groups (AMI and control). Similar results have been reported earlier5,6. Altman et al6 studied 159 patients with arterial atherosclerotic disease and compared the result with 203 patients with a heart valve prostheses and no demonstrable CAD. They concluded that C. pneumoniae infection was not an independent risk factor for CAD. In another prospective study, C. pneumoniae IgG seropositivity did not show any risk of future likelihood of myocardial infarction, and no association was found between C. pneumoniae infection and CAD8.

Certain lipid risk factors (triglycerides, HDL and lipid tetrad index) were significantly higher in the Chlamydia seropositive group compared to the seronegative group. Chlamydia induces production of several cytokines leading to altered lipid metabolism, accumulation of serum triglycerides and a decrease in HDL7–9. Lipopolysaccharide, a bacterial component, binds in human serum to both HDL and LDL and makes LDL toxic to endothelial cells. Cytokines are potent inducers of neutrophils and free radical generation, which may facilitate oxidation of LDL, a key event in atherogenesis. Leukocyte activation may also lead to propagation of the atherosclerotic process7,10. Our study showed an association between C. pneumoniae antibodies and lipid risk factors.

It has been shown that despite a seronegative status, C. pneumoniae can be detected in atheromatous plaques by immune-cytochemistry, cell culture and polymerase chain reaction8,10. A significant association was found between C. pneumoniae seropositivity and an adverse lipid profile, indicating a possible indirect effect of infection with CAD.

Satpathy & associates from India12 studied 62 end anteriotomy specimens of discarded coronary arteries of the CAD patients. Association between C. pneumoniae infection and CAD could not be established by genome or antigen detection. Goyal et al13 investigated 30 CAD patients with no conventional risk factors scheduled for CABG and healthy blood donors. C. pneumoniae seropositivity was significantly, higher in CAD patients.

Jha et al14,15 screened for C. pneumoniae, H. pylori, CMV and HSV-1 in different vascular locations of CAD patients using quantitative real-time (RT) PCR and suggested that C. pneumoniae may have caused chronic persistent infection in CAD. Our study in a small number of CAD patients also suggested continuing chronic infection.

In conclusion, no direct effect of infectious agents as causal for CAD could be shown. Our results showed an association between C. pneumoniae seropositivity and an adverse lipid profile. Further work needs to be done to confirm whether infectious agents have any causal effect in CAD.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial support received from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, and thank Dr P. Maisch, Heart Centre, Marburg, Germany, for his suggestions as consultant.

References

- 1.Preventing chronic diseases – a vital investment. Geneva: WHO; 2005. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the Interheart study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahl VK, Prabhakaran D, Karthikeyan G. Coronary artery disease in Indians. Indian Heart J. 2001;53:707–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisch B, Herzum M, Schaefer JR. Is coronary artery disease an infectious disease? CVD Prevention. 1998;1:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danesh J, Wong Y, Ward M, Muir 1. Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, or cytomegalovirus: population based study of coronary heart disease. Heart. 1999;81:245–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman R, Rouvier J, Scazziota A, Absi RS, Gonzalez C. Lack of association between prior infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae and acute or chronic coronary artery disease. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:85–90. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960220206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen SJ, Eckmann L, Quayle AJ, Shen L, Zhang YX, Anderson DJ, et al. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to Chlamydia infection suggest a central role for epithelial cells in Chlamydial pathogensis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:77–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI119136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong YK, Dawkins KD, Ward ME. Circulating Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA as a predictor of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1435–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumber C, Veevitch RJ, Dayer JM. Modulation of endotoxic activity of lipopolysaccharide by high density lipoprotein. Pathology. 1991;59:378–83. doi: 10.1159/000163681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ieven MM, Hoymans VY. Involvement of Chalmydia pneumoniae in atherosclerosis: More evidence for lack of evidence. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:19–24. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.19-24.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collee JG, Daguid JP, editors. Mackie & McCartney practical medical microbiology. 13th ed. Edinburg: Churchil & Livingstone; 1989. p. 776. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satpathy G, Bhan A, Sharma A, Kar UK. Detection of Chalmidophila pneumoniae (Chalmydia pneumoniae) in endarteroctomy specimens of coronary heart disease patients. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:658–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal P, Kale SC, Chaudhry R, Chauhan S, Shah N. Association of common chronic infections with coronary artery disease in patients without any conventional risk factors. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha HC, Wardhan H, Gupta R, Verma R, Prasad J, Mittal A. Higher incidence of persistent chronic infection of Chlamydia pneumoniae among coronary artery disease patients in India is a cause of concern. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jha HC, Srivastava P, Divya A, Prasad J, Mittal A, et al. Prevelence of Chlamydiophila pneumoniae is higher in aorta and coronary artery than in carotid artery of coronary artery disease patients. APMIS. 2009;117:905–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]