Abstract

Cellular development requires reprogramming of the genome to modulate the gene program of the undifferentiated cell and allow expression of the gene program unique to differentiated cells. A number of key transcription factors involved in this reprogramming of preadipocytes to adipocytes have been identified; however, it is not until recently that we have begun to understand how these factors act at a genome-wide scale. In a recent publication we have mapped the genome-wide changes in chromatin structure during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and shown that a major reorganization of the chromatin landscape occurs within few hours following the addition of the adipogenic cocktail. In addition, we have mapped the genome-wide profiles of several of the early adipogenic transcription factors and shown that they act in a highly cooperative manner to drive this dramatic remodeling process.

Keywords: adipocyte differentiation, C/EBPbeta, ChIP-seq, chromatin structure, DHS-seq, DNase I hypersensitive sites, hotspot

Complex networks of transcription factor interactions form the genetic basis for development of specific cell lineages in multicellular eukaryotic organisms. The analysis of these networks has focused classically on the identification of key factors that play a dominant role in specific cell types. A common assumption is that the factors driving these development pathways will bind and act at their cognate regulatory elements. Fusion of the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) methodology with deep sequencing techniques now allows the high resolution determination of transcription factor binding profiles on the genome scale.1

A key finding in early applications of this approach is that the vast majority of potential DNA recognition sites for many factors are not bound in a given cell type. As an example, only a few thousand binding sites are observed for nuclear receptors,2-5 whereas there are potentially 2–5 × 106 recognition elements for these receptors in the mammalian genome. Thus, a major factor in developmental biology is understanding the mechanisms that control access for a given set of transcription factors to their binding sites in genomic chromatin.

Genome-wide analysis of nuclear receptor binding events has shown that most interactions are associated with localized chromatin transitions that can be characterized as nuclease hypersensitive sites (DHS).5,6 These transitions can now be mapped on the genome scale at high resolution.7,8 This approach brings enormous power to the characterization of regulatory elements potentially active in a given cell type. Recent global analysis of hypersensitive transitions associated with binding of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR)5 reveals two classes of DHS elements. A given transition can be directly induced by the activating receptor (de novo sites), or pre-exist in the chromatin structure (pre-programmed sites). Thus, in some cases (de novo), the remodeling process is initiated by interactions between the receptor and chromatin remodeling enzymes. These de novo sites correspond to our classic understanding of receptors as proteins that can act as pioneering factors, able to always address their response elements. However, it is now clear that in the majority of cases receptor binding sites are already configured in the remodeled state (pre-programmed), with this “pre-opened” state regulated by other activities.5 Both of these classes are strongly cell selective in their occupancy. That is, chromatin is configured in specific cell types such that both the de novo and pre-programmed events for a given receptor occur in a limited set of tissues.9

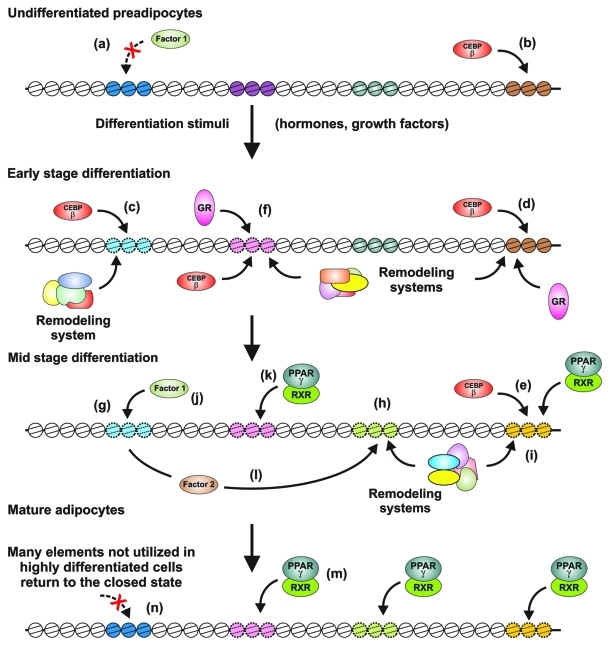

These observations suggest a general model for the action of regulatory networks in developing cells. As cells evolve through a given developmental pathway, the compendium of transcription factors present and active will diverge. As subsets of localized chromatin elements that are “closed” in early stages of development are addressed by an increasingly complex set of site-specific DNA binding proteins, new sites are opened and become available for binding by the panoply of factors present in that cell (Fig. 1). In this epigenetic process, there are a continued and evolving interactions between the chromatin state in a given cell and the factors that predominate in that cell.

Figure 1. Modulation of the chromatin landscape during adipocyte differentiation. Prototypical regulatory elements with an inaccessible chromatin structure are indicated with dark colors and smooth nucleosome outlines. Accessible, active elements (detected as DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS)) are diagrammed with light colors and broken nucleosome outlines. In undifferentiated preadipcytes, many factors are excluded (a) from binding sites. Early factors, such as C/EBPβ, can access selected sites (b), but these elements may (c), or may not (d), become functional until later stages (e). When differentiation is initiated, activation of selected hormone receptors and growth factors leads to specific reprogramming of the chromatin landscape (c, f), allowing new access to regulatory elements not available in undifferentiated cells. C/EBPβ and GR (c, d, e) are particularly active in these processes, and cell specific remodeling systems are also required. The resultant cascade leads to further chromatin opening events (h, i), and new access (j, k, e) by critical factors, such as PPARγ and its heterodimerization partner RXR, that further modulate the genetic program. Some newly expressed regulatory proteins (l) also participate in chromatin reprogramming, and open additional enhancer elements. In mature adipocytes, a large number of elements (including PPAR-gamma binding sites) specific to the differentiated state are now active (m), while other sites (n) not utilized in highly differentiated cells return to the closed state.

Direct evidence supporting this general model was recently reported by Siersbæk et al.10 In this work we used DHS analysis combined with deep sequencing (DHS-seq) to investigate the changes in chromatin structure during adipocyte differentiation of murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Our results showed that the major remodeling during adipogenesis occurs within the first four hours after addition of the adipogenic cocktail. During this time the number of DHS sites increase more than 3-fold. By employing de novo motif analyses of the de novo remodeled sites combined with subsequent ChIP-seq of the candidate factors we showed that this dramatic remodeling is correlated with binding of many transcription factors of the first wave of adipogenic transcription factors. These include GR, retinoid X receptor (RXR), signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a (Stat5a) and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) β and -δ. Most DHS sites bind several of these different early transcription factors, and we found about 1000 ‘hotspots’ that bind all transcription factors investigated. The extent of de novo remodeling correlates positively with the number of factors bound to the DHS sites, indicating that the transcription factors cooperate in remodeling. Binding of GR correlates particularly well with remodeling, suggesting that GR plays a special role in this de novo remodeling process.

A key question is how the transcription factors are guided to these hotspots and to other binding sites in the preadipocytes. Interestingly, C/EBPβ occupies about a third of all hotspots prior to remodeling and is required for efficient binding of other factors to the hotspots. This indicates that C/EBPβ can bind to closed chromatin and function as an initiating factor facilitating the recruitment of other transcription factors to these primed sites. However, for the remaining two thirds of the hotspots C/EBPβ occupancy is induced along with the remodeling. It remains an open question whether these hotspots are marked in the preadipocyte, by binding of other priming factors or by specific epigenetic marks. Another interesting possibility is that these sites are recognized and become occupied and remodeled because there are a sufficiently high number of transcription factors that synergize in binding to these sites. In support of the latter, the binding of transcription factors to this type of sites is highly interdependent such that knockdown of one factor interferes with binding of the others.

Notably, the early remodeling in preadipocytes occurs long before the major adipogenic transcription factors are expressed and the adipocyte specific gene program is activated. Some of the early DHS sites disappear again (Fig. 1); this class of sites is enriched in the vicinity of genes that are transiently induced, indicating that many of them represent enhancers that are active very early in adipogenesis. However, other DHS sites persist in the mature adipocytes; many are associated with genes that are only induced later in adipogenesis when the major adipogenic transcription factors such as peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARγ) are active. This indicates that remodeling in the preadipocyte may also function to prime adipogenic enhancers for subsequent binding and activation. In fact, 71% of the differentiation-induced DHS sites in the mature adipocyte are already remodeled by 4 h. Similarly, 33% of all binding sites of PPARγ in the mature adipocyte are already remodeled in the preadipocyte, i.e., long before this transcription factor is expressed. This indicates that the formation of some late enhancers is pioneered by early remodeling driven by the early wave of adipogenic transcription factors.

In the classic understanding of cell development, attention has focused primarily on the site-specific DNA binding proteins that contribute to the developmental pathway in a given lineage. However, we now understand that access of these factors to their response elements is strongly influenced by the creation and maintenance of localized chromatin transitions (Fig. 1). Transcription factors require the assistance of ATP-dependent remodeling proteins to effect these chromatin reorganization events, and a highly complex family of remodeling systems have now been characterized. The distribution of these selective remodeling systems is also highly regulated, thus creating another layer of regulation. A thorough and complete model of cell differentiation and development will require an integrated understanding of the mechanics by which cell specific factors interact with selective remodeling systems to affect a given transcriptional profile. Furthermore, the realization that transcription factors bind cooperatively to hotspots underscores the importance of cellular context and the complex interaction of multiple transcription factors in facilitating cell selective factor access to chromatin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Danish Natural Science Research Council, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/18928

References

- 1.Robertson G, Hirst M, Bainbridge M, Bilenky M, Zhao Y, Zeng T, et al. Genome-wide profiles of STAT1 DNA association using chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Methods. 2007;4:651–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupien M, Eeckhoute J, Meyer CA, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Li W, et al. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell. 2008;132:958–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen R, Pedersen TA, Hagenbeek D, Moulos P, Siersbaek R, Megens E, et al. Genome-wide profiling of PPARgamma:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2953–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy TE, Pauli F, Sprouse RO, Neff NF, Newberry KM, Garabedian MJ, et al. Genomic determination of the glucocorticoid response reveals unexpected mechanisms of gene regulation. Genome Res. 2009;19:2163–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.097022.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John S, Sabo PJ, Thurman RE, Sung MH, Biddie SC, Johnson TA, et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat Genet. 2011;43:264–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John S, Sabo PJ, Johnson TA, Sung MH, Biddie SC, Lightman SL, et al. Interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with the global chromatin landscape. Mol Cell. 2008;29:611–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hesselberth JR, Zhang Z, Sabo PJ, Chen X, Sandstrom R, Reynolds AP, et al. Global mapping of protein-DNA interactions in vivo by digital genomic footprinting. Nat Methods. 2009;6:283–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Whittle J, Webb BD, Tai D, Davis S, et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) Genome Res. 2006;16:123–31. doi: 10.1101/gr.4074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biddie SC, John S, Sabo PJ, Thurman RE, Johnson TA, Schiltz RL, et al. Transcription factor AP1 potentiates chromatin accessibility and glucocorticoid receptor binding. Mol Cell. 2011;43:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siersbæk R, Nielsen R, John S, Sung MH, Baek S, Loft A, et al. Adipogenic development is associated with extensive early remodeling of the chromatin landscape and establishment of transcription factor ‘hotspots’. EMBO J. 2011;30:1459–72. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]