Abstract

Plant metacaspases (MCPs) are conserved cysteine proteases that have been postulated as regulators of programmed cell death (PCD). Although MCPs have been proven to have PCD relevant functions in multiple species ranging from fungi to plants, how these proteases are modulated in vivo remains unclear. Aside from demonstrating that these proteases are distinct from metazoan caspases due to their different target site specificities, how these proteases are used to tightly regulate cell death progression is a key question that remains to be resolved. Some recent studies on the biochemical characteristics of type-II MCP activities in Arabidopsis may begin to shed additional light on this aspect. The in vitro catalytic activities of recombinant AtMC4, AtMC5 and AtMC8 are found to be Ca2+-dependent while recombinant AtMC9 is active under mildly acidic conditions and not dependent on stimulation by Ca2+. Alterations of cellular pH and Ca2+ concentration commonly occur during various stresses and may help to orchestrate differential activation of latent MCPs under these conditions. Recent peptide mapping for recombinant AtMC4 (also called Metacaspase-2d) followed by site-specific mutagenesis studies have revealed multiple potential self-cleavage sites with the identification of a conserved lysine residue (Lys-225) as the key position for enzyme function both in vitro and in vivo. The multiple self-cleavage sites in MCPs may also facilitate desensitization of these proteases and can provide a means for fine-tuning their proteolytic activities in order to achieve more sensitive control of downstream processes.

Keywords: autolysis, calcium, cleavage activation, Metacaspase, programmed cell death, protease

MCPs—Conserved Cell Death Regulators in Plants

Since plant and fungal metacaspases (MCPs) were identified based on their structural homologies with the central apoptosis regulator caspases,1 their role in programmed cell death and whether they perform caspase-like functions have been actively debated.2 During the past decade, experimental evidence in multiple species using reverse-genetic methods have supported type-II MCPs as positive mediators of PCD.3-5 Among the 6 type-II MCPs in Arabidopsis, the nomenclature of which has recently been unified,2 AtMC8 was found to be involved in UV-C and oxidative stress-induced PCD while the catalytic activity of AtMC4 is demonstrated to be essential for its in planta function during oxidative stresses as well as toxin-induced PCD.4,5 Among the three type-I MCPs in Arabidopsis, two of them were recently shown to antagonistically modulate PCD with the anti-death function of AtMC2 being independent of its catalytic activity.6 Based on these new data, it is appropriate to state that MCPs are important cell death regulators in plants, especially under induced-stress scenarios. Since the commitment to cell suicide is not a trivial decision, MCP activities are likely to be placed under careful control with multiple buffering and feedback mechanisms to facilitate their response to different signals. Thus, the elucidation of how AtMCP activities are regulated will shed important light on pathways that orchestrate cell death in plants, as well as other cryptic functions of MCPs that have yet to be discovered.2 Here, we will focus on a more extensive discussion related to the implications of our recent biochemical characterization of AtMC4 activation and autolytic deactivation. Comparative analyses between 4 different type-II MCPs indicate both similar and divergent mechanisms of regulation for these proteases.

Control of MCP Activation via Autolytic Cleavage

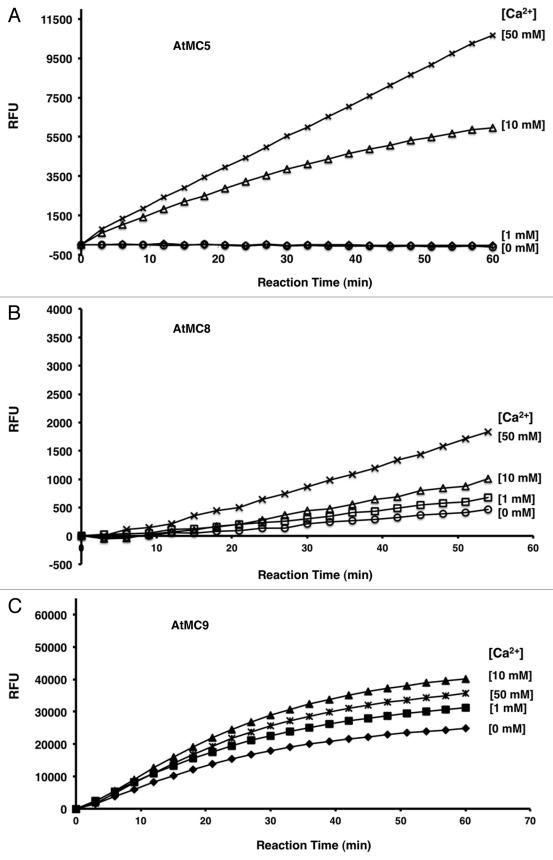

A number of published studies seek to determine the functional and regulatory characteristics of type-II MCPs and these work have recently been reviewed.2 Here, we will focus on the biochemical studies that have been performed recently (results presented here and7) in an effort to determine what mode of post-transcriptional mechanisms are possible to modulate type-II MCPs. The catalytic activity of rAtMC4, rAtMC5 and rAtMC8 are strictly Ca2+-dependent, whereas the activity of rAtMC9 is clearly independent of Ca2+ (Fig. One and7). In most ways, rAtMC5 behaved identically to that of rAtMC4, which is consistent with their high degrees of sequence identities (71.8%). Similar functional characteristics is expected to exist for the type-II MCP mcII-Pa of Norway spruce,8 which is a likely homolog of AtMC4 based on their high sequence homologies (64.3%). On the other hand, AtMC8 shows much more divergence in sequence with only 41.6% identities to AtMC4. In vitro, rAtMC8 showed lower apparent FSRase activity when compared with the other 3 type-II AtMCPs and it also does not show any apparent evidence for autoinactivation after Ca2+ stimulation (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Calcium dependence of FSRase activities with 3 Type-II MCPs in crude bacteria lysate. (A) FSRase activities of rAtMC5 in crude BL21(DE3)pLysS lysate. Activity of rAtMC5 in crude lysate form compared in buffers with CaCl2 varied between 0, 1, 10 and 50 mM. (B) Activity of rAtMC8 with different (0, 1, 10 and 50 mM) CaCl2 concentrations in the assay buffer. (C) Activities of rAtMC9 in the presence of varying amounts (0, 1, 10 and 50 mM) of CaCl2 in the assay buffer. For AtMC5 and AtMC8, the assay buffer consisted of 100 mM TRIS-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 100 μM FSR-MCA. Since, AtMC9 was previously shown to prefer acidic conditions, a different buffer and pH (100 mM MES, pH5.5) was used in place of TRIS-HCl. Due to much higher apparent specific activity of the recombinant protein, the enzymatic activity for rAtMC9 was assayed after a 5-fold dilution of the bacteria lysate. The relative amount of recombinant protein in each of the lysates were first normalized by comparing the expressed protein’s levels using protein gel blots with either anti-T7 antibodies or anti-AtMC4 polyclonal antibodies produced from rabbits.5 With FSR-MCA, there is less background activity observed with crude bacterial lysates than with GRR-MCA (data not shown). Thus, we opted to use this artificial substrate for our assay. RFU: relative fluorescence unit.

Our recent studies with AtMC4 have shown that Ca2+ is essential for activation of intra-molecular cleavage of the recombinant protein in vitro and the formation of an active site in the protease as revealed by sequence-specific binding to a biotinylated peptide substrate.7 The functional importance of intra-molecular cleavage in the activation of MCPs is corroborated by mutagenesis experiments with AtMC4 and AtMC9 that showed disruption of the key P1 residue at the mapped cleavage site (K225 for AtMC4; R183 for AtMC9) abolished catalytic activities in the respective enzymes.7,9 Moreover, AtMC4K225G failed to complement the yeast Δyca1 mutant in contrast to wild-type AtMC4, suggesting the autocatalytic processing is indispensable for AtMC4’s proposed role as a positive PCD regulator in vivo.7 Finally, recent immunological studies with anti-AtMC4 antiserum has revealed evidence for increased processing of this plant MCP in Arabidopsis upon activation of PCD by treatment with the fungal toxin fumonisin B1 or during activation of the hypersensitive response by an incompatible bacterial pathogen.5 These results are thus consistent with the proposal that the cleavage activation of AtMC4 is required for its function as a cell death mediator during biotic stress signaling.

The demonstrated requirement of cleavage activation for type-II AtMCPs is reminiscent of that which is known for metazoan caspases and may fit well with the observed similarities between the predicted tertiary structures of these enzymes.1 The functional importance of the mapped cleavage site in AtMC4 (K225) is further supported by sequence alignment of the 6 type-II AtMCPs9 where this position is either a lysine or arginine and is immediately followed by a stretch of relatively conserved residues within a span of about 40 amino acid residues. Peptide mapping of cleavage products of recombinant mcII-Pa from spruce has identified two other potential autoprocessing sites flanking this conserved residue.3 We have tested the role of the amino acid residues at the two analogous positions (R190 and K271) in rAtMC4, the Arabidopsis MCP with the highest sequence homologies to mcII-Pa throughout the whole length of the two proteins.7 Mutations at one or both of these residues, however, showed that they are not required for Ca2+-dependent activation of rAtMC4, thus indicating that they are subsequent autolytic target sites instead of the key initial cleavage events that are required for activation of the zymogen. Interestingly, these two sites are not conserved in all the type-II AtMCPs9 although it is highly conserved between close homologs between species,7 thus suggesting that these additional cleavage sites could play important roles in the functional diversification between different MCPs within a species. It is also interesting to note that type-I AtMCPs such as AtMC1 and yeast YCA1, which are not strictly dependent on Ca2+ for their in vitro activity,10 has a much shorter intervening “linker” region between the p20 and p10 domains that is present in all MCPs.9 Within this ~20 amino acid stretch that is highly conserved among type-I AtMCPs, there are only two invariant basic residues (R246 and K253 in AtMC1). Based on structural considerations, we think these are good candidates as potential cleavage activation site for type-I MCPs and this prediction can be readily tested via site-specific mutagenesis followed by in vitro assays with recombinant proteins of type-I MCPs.10

It is also intriguing to note that although both recombinant AtMC4 and AtMC9 are shown to be activated via autolytic cleavage at the same conserved site, the former requires the addition of high concentrations of Ca2+ to achieve high activity in vitro while the latter does not. Given the similarities of the predicted p20 and p10 domains in type-II AtMCPs,9 this difference may reflect the more extreme divergence in sequence between AtMC9 and the other 5 type-II AtMCPs, especially within the region between the p20 domain and the conserved cleavage activation site. Future domain swap experiments between AtMC4 and AtMC9 may help to identify the key residues that are responsible for the Ca2+-dependency observed in AtMC4, AtMC5 and AtMC8 (Fig. 1, 2 and7). In this regard, the requirement of Ca2+ for cleavage-dependent activation of MCPs may provide a regulatory switch for cells to control some of these proteases through altering Ca2+ fluxes within cells. However, since physiological Ca2+ commonly fluctuate in the μM range11 whereas MCPs require more than 1 mM of Ca2+ for their in vitro activities (Fig. 1, 2 and7), it is not obvious how type-II MCPs can be catalytic active in plant cells. Two alternative hypotheses have been proposed to reconcile the discrepancy between the Ca2+ concentration present in cells and that apparently needed for rMCPs activities in vitro – 1) additional cellular factors may sensitize some MCPs to Ca2+, thus lowering the effective concentrations of this cofactor required in vivo for their activation, and 2) high concentrations of Ca2+ may fortuitously mimic or inhibit certain protein-protein interactions that normally occur in vivo during MCP activation and thus induce the proper conformational change needed to activate some rMCPs in vitro.7 For either of these scenarios, defining the residues responsible for the difference observed between rAtMC4 and rAtMC9 should provide useful tools to address these possibilities and will ultimately shed light on the molecular basis/determinants for autoactivation of these enzymes.

Figure 2.

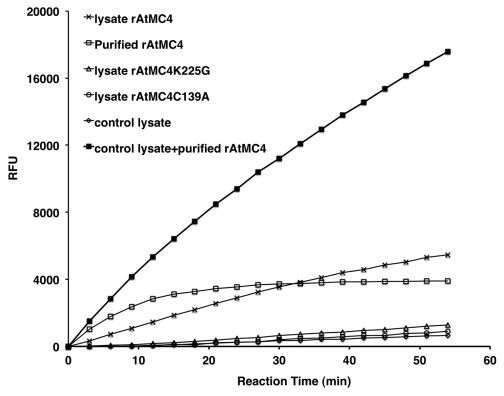

Enhancement and sustained FSRase activity of AtMC4 in the presence of bacterial lysate. Activities of control lysate and lysates from bacteria expressing rAtMC4, rAtMC4K225G, rAtMC4C139A, and purified rAtMC4 are compared. In addition, purified rAtMC4 was also mixed with control lysate to test for enhancement of the activated FSRase activity. The reaction buffer contained 100 mM TRIS-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 100μM FSR-MCA. We constructed rAtMC4 expression vectors in two different vector backgrounds (pET23a and pET28a) to produce histine-tagged versions of this protease with the hexahistidines either at the N- (His-AtMC4) or C-terminus (T7-AtMC4-His), respectively. In crude lysates, these two different versions of rAtMC4 fusions behaved identically in terms of FSRase activity (data not shown). For purification of rAtMC4, the His-AtMC4 version of the fusion protein was used since the T7-AtMC4-His fusion gave very low yield in several attempts. For comparison with the two AtMC4 variants with point mutations at K225 and C139, the T7-AtMC4-His version of the fusion protein was shown in the figure since they were all constructed in the same expression vector background. In these cases, only crude lysates were used for comparison. RFU: relative fluorescence unit.

Irreversible Autolysis of AtMCPs: a Potential Desensitization Mechanism?

As key regulators for critical decisions such as cellular suicide, proteases can be regulated in at least two stages during their production in order to avoid unintended activation of downstream effectors: 1) tight transcriptional and/or translational regulation to control the steady-state levels of the zymogen, and 2) post-translational control mechanisms to regulate the equilibrium between dormant and active forms of the enzyme. Although the 9 different AtMCP-encoding genes in Arabidopsis showed different tissue-specific patterns of expression, most of them can be found to express in seedlings as well as in multiple tissues of the mature plant.5 AtMC4 is the most highly expressed member and it is expressed in various tissue types. Thus, transcriptional regulation is unlikely to be sufficient for the tight control of AtMC4 activity in vivo. For AtMC9, which expresses preferentially in root tissues, two types of post-translational control have been described as candidate pathways to maintain at least a portion of this enzyme in an inactive pool: S-nitrosylation at the active site cysteine12 of the zymogen and direct physical interaction of the activated protease with the suicide inhibitor AtSerpin1.13 Although preliminary data in our lab also indicated that rAtSerpin1 could inhibit rAtMC4 activities in vitro (Watanabe, Budai-Hadrian, Fluhr and Lam, unpublished data), the role of these potential mechanisms to regulate AtMCP function in vivo remains to be demonstrated. Nevertheless, interaction between serpins and type-II AtMCPs could be one potential mechanism for modulating multiple AtMCP proteases.

More recently, autolytic deactivation of activated type-II MCPs was shown to be a third post-translational mechanism for suppressing the activity of activated MCPs.7 Recombinant proteins for three of the type-II MCPs (AtMC4, AtMC5 and AtMC9) are found to exhibit characteristics of self-inactivation after the initial cleavage activation of these enzymes in vitro (Figs. 1A, C and7). Using a polyclonal antiserum, time course analyses of purified rAtMC4 self-cleavage patterns upon activation by Ca2+ indicated that extensive autolysis could be responsible for the irreversible loss of catalytic activities.7 Interestingly, we recently found that rAtMC4 in E. coli bacteria lysate showed much slower self-inactivation when compared with purified rAtMC4 in vitro (Fig. 2). Using the substrate FSR-MCA, we observed negligible background activity with crude lysate prepared from the “empty” vector transformed bacteria control. Similar low background activity was observed with crude lysates prepared from bacteria expressing the K225G and C139A variants of rAtMC4, thus confirming that the activity observed with the crude lysate containing rAtMC4 is bona fide proteolysis of the substrate by activated enzyme in the presence of Ca2+. As Figure 2 shows, when crude lysate is used, slower activation of the latent rAtMC4 activity is observed compare with purified rAtMC4. The observed FSRase activity persisted in the crude lysate and remained somewhat active even after 50 min. of incubation whereas the purified enzyme was rapidly inactivated by 20 min., as recently reported.7 When compared with the 3 other type-II AtMCPs studied here, both rAtMC5 as well as rAtMC9 showed characteristics of autoinactivation while rAtMC8 did not (Fig. 1). It is interesting to note that AtMC8 has been shown to be strongly upregulated at the transcription level by oxidative stress.3 Thus, an autoinactivation mechanism may not be necessary to tightly control this MCP’s activity since the basal level of this MCP should be very low.

In an effort to verify if some bacterial components of the crude lysate is suppressing the autoinactivation of rAtMC4, we “reconstituted” the rAtMC4 lysate by mixing purified rAtMC4 with the control lysate prepared from the “empty” vector transformed bacteria. Figure 2 shows that this indeed resulted in a dramatic increase in the stability of the purified rAtMC4 upon its activation by Ca2+. This observation is in contrast to our previous study in which we showed that addition of 1 mg/mL of BSA (bovine serum albumin) did not suppress the autoinactivation.7 Together, these two results indicate that a more complex protein mixture, such as the crude lysate, may help suppress the autolysis by providing a large excess of target sites for the activated rAtMC4. It is possible that BSA may not have optimal cleavage sites for rAtMC4 and thus cannot compete efficiently with the intra-molecular target sites on AtMC4 to suppress the autoinactivation. In any case, our studies raise the possibility that some MCPs can be controlled by modulation of their autolysis through intra- and/or intermolecular cleavages. This irreversible inactivation of MCPs may be enabled when these zymogens are expressed in the absence of a cell death signal and reduced stability of their active forms need to be insured. Upon perception of cell death signals, suppressors of their autolysis may be used to prolong the half-life of activated MCPs and thus enhance the cleavage of their downstream targets. To test this idea, it may be interesting to determine the bacterial lysate components that can render purified rAtMC4 refractory to autolysis, as well as to test if the kinetics of AtMC4 self-inactivation is indeed modulated during PCD activation in plant cells.

Future Perspectives

After more than a decade since their identification,1 there are now good genetic evidence for the involvement of MCPs as regulators of PCD activation in higher plants. However, their mechanism in exerting this important control remains to be defined in molecular terms. In most cases that have been examined so far, active proteolysis of downstream targets is likely involved, although AtMC2 may be an exception.6 In characterizing the biochemical properties of a number of recombinant plant MCPs in vitro, it has became evident that the activities of these enzymes are tightly controlled. Elucidating these post-translational controls on MCP activities should provide new clues to the molecules and pathways that serve to keep these proteases dormant until the proper threshold of cell death signals are perceived.

Acknowledgment

Work on metacaspases and programmed cell death in the Lam lab is supported by a grant (IOS-0744709) from the National Science Foundation to E.L.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/18247

References

- 1.Uren AG, O'Rourke K, Aravind LA, Pisabarro MT, Seshagiri S, Koonin EV, et al. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Mol Cell. 2000;6:961–7. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsiatsiani L, Van Breusegem F, Gallois P, Zavialov A, Lam E. Metacaspases. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1279–88. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozhkov PV, Suarez MF, Filonova LH, Daniel G, Zamyatnin AA, Jr., Rodriguez-Nieto S, et al. Cysteine protease mcII-Pa executes programmed cell death during plant embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14463–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506948102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He R, Drury GE, Rotari VI, Gordon A, Willer M, Farzaneh T, et al. Metacaspase-8 modulates programmed cell death induced by ultraviolet light and H2O2 in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:774–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe N, Lam E. Arabidopsis metacaspase 2d is a positive mediator of cell death induced during biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant J. 2011;66:969–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coll NS, Vercammen D, Smidler A, Clover C, Van Breusegem F, Dangl JL, et al. Arabidopsis type I metacaspases control cell death. Science. 2010;330:1393–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1194980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe N, Lam E. Calcium-dependent activation and autolysis of Arabidopsis metacaspase 2d. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10027–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez MF, Filonova LH, Smertenko A, Savenkov EI, Clapham DH, von Arnold S, et al. Metacaspase-dependent programmed cell death is essential for plant embryogenesis. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R339–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vercammen D, van de Cotte B, De Jaeger G, Eeckhout D, Casteels P, Vandepoele K, et al. Type II metacaspases Atmc4 and Atmc9 of Arabidopsis thaliana cleave substrates after arginine and lysine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45329–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe N, Lam E. Two Arabidopsis metacaspases AtMCP1b and AtMCP2b are arginine/lysine-specific cysteine proteases and activate apoptosis-like cell death in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14691–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bush DS. Calcium regulation in plant cells and its role in signaling. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:95–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.46.060195.000523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belenghi B, Romero-Puertas MC, Vercammen D, Brackenier A, Inze D, Delledonne M, et al. Metacaspase activity of Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated by S-nitrosylation of a critical cysteine residue. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1352–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vercammen D, Belenghi B, van de Cotte B, Beunens T, Gavigan J-A, De Rycke R, et al. Serpin1 of Arabidopsis thaliana is a suicide inhibitor for metacaspase 9. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:625–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]