Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common and most aggressive primary brain tumor. Despite maximum treatment, patients only have a median survival time of 15 months, because of the tumor’s resistance to current therapeutic approaches. Thus far, methylation of the O 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter has been the only confirmed molecular predictive factor in glioblastoma. Novel “genome-wide” techniques have identified additional important molecular alterations as mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and its prognostic importance. This review summarizes findings and techniques of genetic, epigenetic, transcriptional, and proteomic studies of glioblastoma. It provides the clinician with an up-to-date overview of current identified molecular alterations that should ultimately lead to new therapeutic targets and more individualized treatment approaches in glioblastoma.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Molecular, (Epi)genetic, Transcriptional, Proteomic

Introduction

Glioblastoma, or astrocytoma WHO grade IV, is the most fatal primary brain cancer found in humans. Most glioblastomas manifest rapidly de novo, without recognizable precursor lesions. These primary glioblastomas present in elderly patients with a brief clinical history and are characterized by rapid progression and short survival time. A small group of young patients has a history of epilepsy caused by low-grade gliomas which, within years, progress to secondary glioblastoma. A secondary glioblastoma occurs in ~5% of glioblastoma patients, and can only be diagnosed with clinical (neuroimaging) or histological evidence of its evolution from a less malignant glioma [1].

The standard treatment for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients is gross total removal, if possible, followed by the combination of the alkylating cytostatic drug temozolomide (TMZ) and RT [2, 3]. Median overall survival is 15 months only [3], although for a rare group of long-term survivors (2–5%) survival time exceeds 3 years [4, 5]. Differences between patients and their performance status lead to variation in survival, which can be calculated for individual patients by means of nomograms [6]. A better prognosis is associated with younger age, better performance status, and more extensive surgical resection followed by TMZ and RT [6]. In contrast with many other malignancies, however, there have only been small improvements in the glioblastoma patient’s prognosis over recent decades. Nevertheless, understanding of the molecular alterations in signaling pathways and the consequent pathology in glioblastoma has greatly increased in recent years and is beginning to match that of other types of cancer.

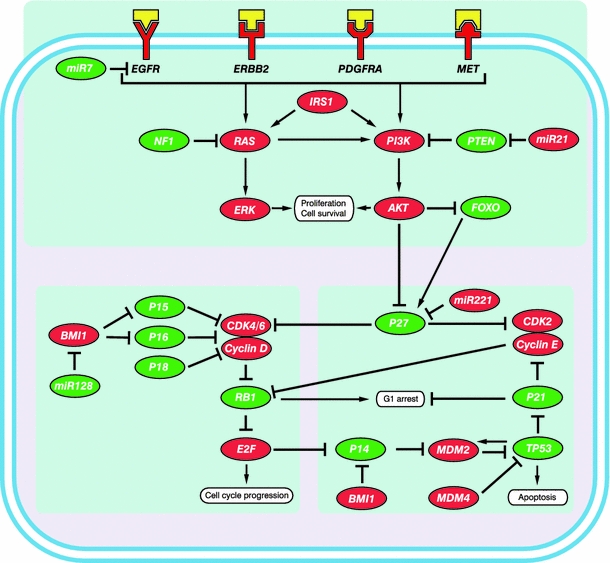

This review provides an overview of the molecular alterations in glioblastoma (Fig. 1) [7–9]. They are grouped according to the different mechanisms that underlie transformation to the neoplastic phenotype, starting from (epi)genetic, via transcriptional, to proteomic studies of glioblastoma. The important molecular alterations, which have been identified by novel “genome-wide” techniques, are discussed in relation to gliomagenesis and glioma progression and in relation to clinical subgroups and prognosis. Finally, we discuss the application of these new insights in the light of future prospects for experimental and clinical practice in neuro-oncology.

Fig. 1.

Simplified representation and integration of three commonly altered pathways involved in glioblastoma. Upper panel, the growth factor receptor/PI3K/AKT pathway. The lower panels depict the RB pathway (left) and the P53 pathway (right). Proteins that potentially act as tumor suppressors are indicated in green whereas oncoproteins are indicated in red. The growth factors binding to the receptors have been depicted in yellow

Genomic and genetic variants

Genomic instability

Genomic instability is one of the enabling characteristics of cancer [10]. It can be broadly differentiated into chromosome instability (CIN) and microsatellite instability (MIN or MSI). Cytogenetic studies of glioblastoma have shown that most tumors are near-diploid, and that numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities are common [11]. MSI is rarely observed for non-inherited newly diagnosed glioblastomas, because of inactivation of mismatch repair (MMR) genes [12]. However, in recurrent glioblastomas after TMZ treatment, inactivating mutations have been observed in MSH6, one of the MMR genes. MSH6 mutations have not been associated with detectable MSI as manifested by changes in the length of microsatellite sequences, but with a hypermutator phenotype [7, 9, 13]. As genetic alterations and genomic instability are closely linked with each other, it is an interesting finding that in glioblastoma, tumors from short-term survivors have more genetic alterations than long-term survivors’ tumors [5].

Chromosomal alterations

Techniques

Evolving techniques have identified increasingly more detailed chromosomal alterations.

Karyograms [11], fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses [14], and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) [15, 16] have preceded whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based arrays. Whereas karyograms are able to reveal only gross chromosomal changes, SNP-based arrays have the ability to detect copy number alterations (CNAs), varying from complete chromosomal changes to small intragenic deletions. In addition, it is possible to distinguish signals from individual alleles and therefore reveal copy-number-neutral (CNN) loss of heterozygosity (LOH). Here, a chromosome segment is lost, whereas the corresponding homologous region is duplicated, resulting in a neutral copy number. For example, 17p, which contains TP53, is a significant region of CNN LOH in glioblastoma [7, 8].

Among chromosomal alterations, amplifications and deletions can be distinguished. Of these, the most common in glioblastoma will be discussed here. Reports of incidental translocations are rare in glioblastoma [17]; consequently, translocations may not be important in the development of glioblastoma and will not be discussed further.

Amplifications

Amplification of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene is a characteristic finding in primary glioblastoma (Table 1) [5, 8, 16, 18]. Focal (restricted to a few Mb) and broader (from several Mbs to whole chromosomes) CNAs that include the EGFR gene may have different molecular consequences [16]. Focal amplification of EGFR correlates with EGFR overexpression or mutations and deletions in the EGFR gene, and subsequent activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway [16, 19]. Upregulated PI3K/AKT signaling has been associated with a poor prognosis [20, 21]. Amplification of the complete chromosome 7, containing EGFR, MET [7], and its ligand HGF, has been found to correlate with activation of the MET axis [16]. Furthermore, EGFR amplification is reported to appear as double minutes (small fragments of extrachromosomal DNA), and extra copies of EGFR have also been found inserted into different loci on chromosome 7 [22]. Remarkably, gain of chromosome 7 and amplification of EGFR have been found more frequently in short-term survivors [4, 5], however EGFR alterations are not of prognostic importance in glioblastoma [4, 18, 23].

Table 1.

Frequently identified copy number alterations in glioblastoma

| Chromosome | Cytoband | Alteration | Frequency (%) | Gene symbol | Gene name | Function of encoded protein | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1p32 | Deletion | 3–16 | CDKN2C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C | Regulator of cell cycle | [7, 24] |

| 1 | 1p36 | Deletion | 14–40 | ?a | [8, 26, 30] | ||

| 1 | 1q32 | Amplification | 4–15 | MDM4 | Mdm4 p53 binding protein homolog | Apoptosis | [7, 8, 16, 24] |

| 1 | 1q44 | Amplification | 2–11 | AKT3 | V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7, 24, 26] |

| 2 | 2q22 | Deletion | 7 | LRP1B | LRP1B low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1B | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [8] |

| 3 | 3q26 | Amplification | 0–16 | PIK3CA | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha polypeptide | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7, 9, 16] |

| 4 | 4q12 | Amplification | 15 | KIT | V-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [25] |

| 4 | 4q12 | Amplification | 15 | KDR | Kinase insert domain receptor | Angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and endothelial cell growth | [25] |

| 4 | 4q12 | Amplification | 2–18 | PDGFRA | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7, 8, 16, 24, 25] |

| 6 | 6q26-27 | Deletion | 25 | PARK2 | Parkinson protein 2 | Regulator in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation | [8] |

| 7 | 7p11 | Amplification | 23–66 | EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7–9, 16, 18, 24] |

| 7 | 7q21 | Amplification | 1 | CDK6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | Regulator of cell cycle | [7] |

| 7 | 7q31 | Amplification | 3–19 | MET | Met proto-oncogene | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7, 16, 24] |

| 9 | 9p21 | Deletion | 26–66 | CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Regulator of cell cycle | [7–9, 18, 24] |

| 9 | 9p21 | Deletion | 31–66 | CDKN2B | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B | Regulator of cell cycle | [7, 8, 24] |

| 9 | 9p23 | Deletion | 14–46 | PTPRD | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, D | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [24] |

| 10 | 10q23-24 | Deletion | 5–70 | PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7–9, 16, 18, 24] |

| 12 | 12p13 | Amplification | 2–14 | CCND2 | Cyclin D2 | Regulator of cell cycle | [7, 16] |

| 12 | 12q14 | Amplification | 7–24 | CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | Regulator of cell cycle | [7–9, 16, 24] |

| 12 | 12q14-15 | Amplification | 7–22 | MDM2 | Mdm2 p53 binding protein homolog | Apoptosis | [7, 8, 16, 24] |

| 13 | 13q14 | Deletion | 3–47 | RB1 | Retinoblastoma 1 | Regulator of cell cycle | [7–9, 16, 30] |

| 17 | 17p13 | Deletion | 1–22 | TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | Apoptosis | [7–9, 16] |

| 17 | 17q11 | Deletion | 0–11 | NF1 | Neurofibromin 1 | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [7, 9] |

| 19 | 19q | Deletion | 11–35 | ? | [16, 24, 30] | ||

| 22 | 22q12.3 | Deletion | 53 | TIMP3 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3 | Extracellular matrix | [77] |

A deletion can indicate either a CNN-LOH, an LOH, or a homozygous deletion; a ? indicates that the gene of interest has not yet been identified

aGenes within the region: CAMTA1, PER3, UTS2, TNFSF9, VAMP3, PARK7, MIG6, RERE, GPR157, H6PD [8]

Amplification of 12q13-15, where the oncogenes CDK4 and MDM2 are located, results in the disruption of both the RB and P53 pathways [7, 8, 16, 24]. The genes encoding the receptor tyrosine kinases KIT, KDR, and PDGFRA, adjacently located on chromosome 4q12, are frequently found to be (co)amplified [25]. Other amplified regions containing oncogenes, for example AKT3 [7, 26] and CCND2 [7, 16], are listed in Table 1.

Deletions

LOH of chromosome 10q is the most common genomic alteration found in both primary and secondary glioblastomas [18, 24] (Table 1) and is associated with poor survival [5, 18]. Different regions are frequently lost at chromosome 10, including the regions containing PTEN, MGMT [1, 18], and ANXA7, an EGFR inhibitor [27]. Another frequently deleted inhibitor of EGFR signaling is NFKBIA, which is located on chromosome 14; this deletion is associated with poor survival [28]. Furthermore, loss of chromosome 9p, which contains a variety of tumor-suppressor genes, including CDKN2A, CDKN2B, and PTPRD, is frequently seen [8, 18, 29], especially in short-term survivors [4, 5]. CDKN2A and CDKN2B encode three important cell cycle proteins, p14ARF and p16INK4A, and p15INK4B [5, 8, 15, 16, 18], which are involved in the RB and P53 pathways. Deletion of CDKN2A and CDKN2B is often accompanied by deletion of CDKN2C on chromosome 1p32, which encodes another cell cycle protein p18INK4C [15]. LOH of chromosome 1p is found in both primary and secondary glioblastomas [30]. Longstanding speculation about the potentially located tumor suppressor gene at 1p has recently been advanced by identification of the suggested candidate genes CIC and FUPB1 [31]. Co-deletion of 1p and 19q is frequently seen in oligodendrogliomas and is, in those, associated with prolonged survival [4] and translocations [32]. Although this co-deletion has been observed in glioblastomas, no similar association has been identified. Isolated LOH 19q, however, is frequently observed in secondary glioblastoma [5, 30] and may be a marker of longer survival [5].

Somatic mutations

Techniques

In addition to amplifications and deletions, genes implicated in glioblastoma can be affected by somatic mutations. Mutation analysis has identified mutations activating oncogenes and others inactivating tumor-suppressor genes in glioblastoma [7, 9, 33]. The recommended method used to be direct or Sanger sequencing after amplification of the suspected locus by means of polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Nowadays, improved sequencing techniques are being developed and rapidly applied to facilitate genome-wide mutation analysis [34].

Mutations frequently found in glioblastoma

Mutations in “common” cancer genes, for example TP53 and PTEN, are very frequent in glioblastomas, but are not of prognostic importance (Table 2) [4, 7, 9, 18, 23, 33]. Furthermore, glioblastoma-specific mutations are seen; the EGFRvIII mutant lacks 267 amino acids in the extracellular part, resulting in a constitutively activated receptor that no longer requires its ligand EGF to signal downstream [35]. EGFR point mutations have also been identified in glioblastoma, in the extracellular domain, whereas they are predominantly found in the kinase domain in other tumor types, for example lung cancer [36]. Two extensive mutational studies have provided an overview of the most common mutations affecting glioblastoma (Table 2) [7, 9]. Although mutations in “common” cancer genes, for example BRAF and the RAS genes, have rarely been observed in gliomas (<5%) [37], inactivating mutations and deletions have been identified in their inhibitory tumor suppressor gene NF1 [7]. Mutations in PIK3CA and PIK3R1, coding, respectively, for the PI3K catalytic subunit p110α and regulatory subunit P85α, have been described [7, 9].

Table 2.

Genes frequently found to be mutated in glioblastoma

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Function of encoded protein | Point mutation (%) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 14–15 | [7, 9, 36] |

| ERBB2 | V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2 | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 0–7 | [7, 9] |

| IDH1 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+) | NADPH production | 12–20 | [9, 39–42, 44] |

| NF1 | Neurofibromin 1 | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 15–17 | [7, 9] |

| PIK3CA | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha polypeptide | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 7–10 | [7, 9] |

| PIK3R1 | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 1 (alpha) | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 7–8 | [7, 9] |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 24–37 | [7, 9, 18] |

| PTPRD | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, D | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 0–6 | [9] |

| RB1 | Retinoblastoma 1 | Regulator of cell cycle | 8–13 | [7, 9] |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | Apoptosis | 31–38 | [7, 9, 18] |

The incidence of mutation in glioblastoma is lower than in other solid tumors [38], with the exception of the hypermutator phenotype [13], which, as described above, is found in recurrent glioblastomas after treatment with alkylating agents. This may be caused by MGMT methylation or mutational inactivation of DNA-repair enzymes, for example MSH6 [7, 9, 13].

IDH1 mutations

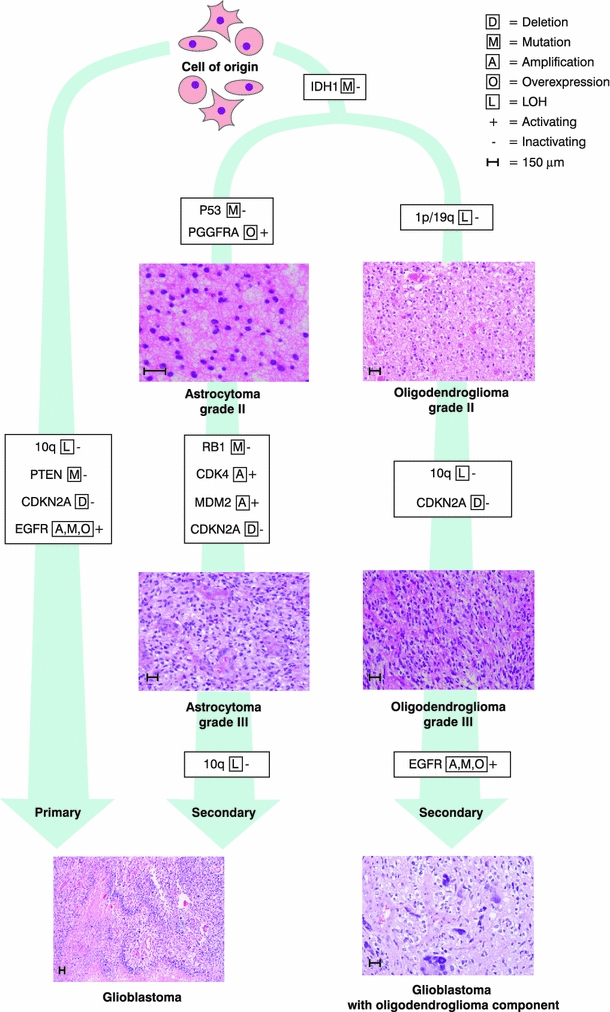

An interesting gene found to contain mutations in glioblastoma is IDH1, which encodes isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and is involved in energy metabolism [9]. IDH1 mutations have been predominantly identified in secondary glioblastomas and low-grade gliomas, with mutations in more than 70% of cases [9, 39–43]; they are found only sporadically in primary glioblastomas [9, 41–44]. Because patients with IDH1 mutated primary glioblastomas are generally younger and have longer median survival and wild-type EGFR, which are characteristics of secondary glioblastomas, it is hypothesized that these are in fact secondary glioblastomas for which no histological evidence of evolution from a less malignant glioma is found. Therefore, IDH1 could be used to differentiate primary from secondary glioblastomas [41]. In different glioblastoma studies IDH1 mutations have been found to be an independent positive prognostic marker [9, 40, 44, 45]. IDH1 mutations have been shown to inactivate the enzyme with subsequent HIF-1a induction [42, 44, 46]. In addition, the mutations result in gain of function to catalyze α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) [47]. Furthermore, 2-HG inhibits histone demethylases and TET 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases. These α-KG dependent dioxygenases are thought to be involved in epigenetic control. This suggests that mutations in IDH1 change the expression of a potentially large number of genes [48]. Given that mutations in IDH1 are an early event in gliomagenesis (Fig. 2) [49], this may implicate widespread alteration of epigenetic control as the key mechanism in gliomagenesis in IDH1 mutated tumors. Furthermore, it might explain the extensive and fundamental differences between mutated and wildtype IDH1 glioblastoma.

Fig. 2.

Genetic pathways toward primary and secondary glioblastoma

Polymorphisms

Family members of glioma patients are more susceptible to glioma and other cancer types [50], suggesting a genetic origin. The most common type of genetic variation is formed by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A SNP is a single base-pair alteration at a specific locus. They can be identified by PCR for single loci or use of SNP-based arrays for whole genome alterations. SNPs have been linked to susceptibility to glioblastomas. In particular, allergies and asthma’s inverse association with glioblastoma have been observed in different studies and have been linked with polymorphisms in HLA and interleukins. This may suggest that immune factors play a role in gliomagenesis [51]. SNP309 in MDM2 has been associated with an increased risk of various types of cancer, but has not been associated as a risk or prognostic factor in respect of glioblastoma in large studies [52]. SNPs in CDKN2B, TERT, and RTEL1 have been described in independent studies as susceptibility loci for high-grade glioma [53, 54]. In a follow-up study, SNPs in DNA double-strand break repair enzymes, for example RTEL1, have been found to correlate with glioblastoma survival [55]. Various other SNPs have been correlated with glioblastoma survival and age of onset [55], however, these studies’ findings have not yet been confirmed.

Gene expression profiling

Techniques and results

Overexpression or underexpression of genes in glioblastoma compared with that in a normal brain or in low-grade gliomas may be an indication of genes that are involved in gliomagenesis (Table 3). Most of the 20,000–25,000 genes encoded by the human genome are known [56], and these have been applied to chips used for micro-arrays. Differences in expression of “unknown” genes can be studied by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE), by use of small expression tags [57]. Large-scale expression studies are usually validated by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for individual genes.

Table 3.

Genes frequently found to be overexpressed in glioblastoma compared with either normal brain tissue or low-grade gliomas

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Function of encoded protein | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | CD44 molecule | Cell-cell interactions, cell adhesion and migration | [20, 62] |

| DLL3 | Delta-like 3 | Notch signaling | [20, 62] |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | [62] |

| FABP7 | Fatty acid binding protein 7 | Fatty acid uptake, transport, and metabolism | [62] |

| IGFBP2 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | Regulation of cell growth | [58–60, 62] |

| IGFBP3 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 | Regulation of cell growth | [58] |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 | Extracellular matrix | [62] |

| SPARC | Secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin) | Extracellular matrix | [62] |

| TNC | Tenascin C | Cell adhesion | [60, 62] |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | Angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, and endothelial cell growth | [20, 59, 60, 62] |

| CHI3L1 | Chitinase 3-like 1(YKL-40) | Extracellular matrix | [20, 60, 62] |

| VIM | Vimentin | Cytoskeletal element | [20] |

A high level of expression of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins, for example IGFBP-2/3 [58], angiogenesic factors, for example vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) [59], and mesenchymal markers, for example YKL-40/CHI3L1, are frequently seen in glioblastoma (Table 3) and have been associated with poor prognosis [60–62]. In contrast, NOTCH signaling genes, for example DLL3, are indicative of better survival [63]. Furthermore, WEE1, a kinase that regulates the G2 checkpoint in glioblastoma cells, is commonly overexpressed in glioblastoma and higher expression has been shown to correlate with worse patient survival [64].

Gene expression profiling studies outperform histology for grading and prognosis

Low-grade astrocytomas have rather specific and consistent expression profiles, whereas for primary glioblastomas there is much larger variation between tumors. Furthermore, secondary glioblastomas have distinct expression profiles and features of the other two types [65]. Expression profiling of different types and grades of glioma has been found to outperform histopathologic grading for prognosis [20, 66–68]. To improve classification of patients with glioblastoma, a gene dosage expression incorporated model based on seven genes (POLD2, CYCS, MYC, AKR1C3, YME1L1, ANXA7, and PDCD4) has been generated. This model can be used to categorize patients in risk groups with different prognosis; a high-risk group in which ≥5 of 7 genes are altered, a moderate-risk (3–4 genes), or a low-risk group (≤2 genes). In this study, MGMT methylation and IDH1 mutational status were not incorporated [69]. A newer predictive model based on expression of four genes (CHAF1B, PDLIM4, EDNRB, and HJURP) has been generated, and is independent of MGMT methylation and IDH1 mutational status. Here, high expression of EDNRB correlates with longer survival whereas the other genes are correlated with higher risk of death. On the basis of the expression of these 4 genes, low-risk and high-risk groups were formed. Interestingly, survival was similar for patients in the low-risk group with wildtype IDH1 and patients in the high-risk group with mutated IDH1 [70].

Expression classification and prognosis according to TCGA studies

Studies by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have incorporated genomic alterations within expression analyses. Distinct molecular subclasses in high-grade glioma have been identified, delineating a pattern of disease progression that resembles stages in neurogenesis, and have been used to classify glioblastomas into proneural, neural, classic, and mesenchymal subtypes [20, 63, 71]. Proneural glioblastomas are characterized by IDH1 mutations, and TP53 and PDGFRA alterations, and correlate with a better prognosis and younger age. Classic glioblastomas are differentiated on the basis of high-level amplification of EGFR, monosomy of chromosome 10, and deletion of CDKN2A. Neural glioblastomas are typified by expression of neuron markers, and resemble normal brain most. Mesenchymal glioblastomas are known for NF1 deletion or mutation and expression of YKL-40/CHI3L1 and MET [20, 71]. Different subtypes of glioblastoma have been shown to behave differently in response to treatment; Classic and mesenchymal subtypes have a survival advantage after TMZ and RT, whereas the proneural subtype of glioblastomas, with relative good prognostic, does not [71]. Stratified clinical trials in which patient inclusion is based on the genetic alterations that have been identified in their tumor samples are necessary to further increase our understanding of the clinical possibilities of these subgroups.

Epigenetics

Epigenetic silencing mechanisms

Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes is a common phenomenon of genomic instability in cancer [10]. Epigenetics are inherited characteristics of gene expression, not related to nucleotide sequences. Examples are promoter hypermethylation, histone deacetylation, histone methylation, other histone modifications which can alter chromatin structure (in)directly, and RNA-silencing mechanisms such as RNA interference and microRNA (miRNA or miR) regulation of gene expression [72]. In contrast with the global DNA hypomethylation found in glioblastoma and other tumors [73], tumor suppressor genes are commonly found to be hypermethylated and, hence, silenced [72]. DNA methylation, histone deacetylation, and miRs are best studied in glioblastoma and are discussed next.

Methylation and histone deacetylation

In glioblastoma, similar to other cancers, global DNA hypomethylation is often seen with hypermethylation of CpG islands in promoter regions. Tumor-suppressor genes frequently found to be silenced by hypermethylation in glioblastoma include CDKN2A, CDKN2B, RB1, PTEN, and TP53. (reviewed elsewhere [74, 75]). Differences in various genes’ promoter methylation have been found between primary and secondary glioblastomas (Table 4) [76–78], long and short-term glioblastoma survivors [75, 79], primary and recurrent tumors, and time to tumor progression [80].

Table 4.

Molecular differences between primary and secondary glioblastoma

| Event | Gene symbol | Gene name | Function of encoded protein | Overall frequency in glioblastoma (%) | Frequency in primary glioblastoma (%) | Frequency in secondary glioblastoma (%) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification | EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 34 | 36 | 8 | [18] |

|

Deletion

|

CDKN2A-P14ARF | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Regulator of cell cycle | 44 | 44 | 44 | [18] |

| CDKN2A-P16INK4A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Regulator of cell cycle | 26–31 | 31–32 | 13–19 | [18] | |

|

LOH

|

10q (including PTEN) | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 69 | 70 | 63 | [30] |

| 13q (including RB1) | Retinoblastoma 1 | Regulator of cell cycle | 23 | 12 | 38 | [30] | |

| 22q (including TIMP3) | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3 | Involved in degradation of the extracellular matrix | 53 | 41 | 82 | [77] | |

| 19q | ? | 27 | 54 | 6 | [30] | ||

|

Methylation

|

MGMT | O 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase | DNA repair | 44 | 43 | 73 | [83] |

| CDKN2A-P14ARF | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Regulator of cell cycle | 14 | 6 | 31 | [18] | |

| CDKN2A-P16INK4A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Regulator of cell cycle | 8 | 3 | 19 | [18] | |

| NDRG2 | N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 | May have a role in neurite outgrowth | 46 | 62 | 0 | [83] | |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 32 | 9 | 82 | [78] | |

| RB1 | Retinoblastoma 1 | Regulator of cell cycle | 25 | 14 | 43 | [76] | |

| TIMP3 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3 | Involved in degradation of the extracellular matrix | 41 | 28 | 71 | [77] | |

|

Mutation

|

IDH1 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+) | NADPH production | 12–20 | 4–12 | 73-88 | [9, 39, 41, 42, 44] |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Regulator of cell signaling, involved in cell proliferation and survival | 24–37 | 25–40 | 4 | [18, 33] | |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | Apoptosis | 31–38 | 28–29 | 65 | [18, 33] |

A ? indicates that the gene of interest has not yet been identified

MGMT methylation

Particularly important in glioblastoma is the methylation status of MGMT, which is a predictive factor for therapy response and hence survival of glioblastoma patients treated with TMZ and RT [2, 23, 81]. MGMT methylation has been observed in 40–57% of glioblastomas; however, specific subgroups have a higher frequency. MGMT methylation has been found to be more frequent in secondary glioblastomas [82], in females [83], and in long-term survivors (LTS) [4], whereas it is rare (5%) in recurrent glioblastomas [84]. Conflicting results have been reported regarding the methylation status of MGMT as a positive prognostic marker [74, 75, 83]. TMZ and other alkylating agents modify the O 6-position in guanines thereby forming critical DNA lesions that progress to lethal DNA cross-links which prohibit cell replication. The DNA repair enzyme MGMT is able to remove alkyl groups, thus introducing resistance to TMZ treatment. However, when the promoter of MGMT is methylated, MGMT is not transcribed and therefore cannot repair DNA damage caused by TMZ, making TMZ more efficient. The best means of assessment of the MGMT methylation status has been debated; the most widely recommended method is methylation-specific PCR (MSP) [85]. Recently, the methylation status of the FNDC3B, TBX3, DGKI, and FSD1 promoters was identified to be important in patients with MGMT-methylated tumors who did not respond to TMZ and RT treatment [79]. MGMT methylation is also associated with pseudo-progression after concomitant radiochemotherapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients [86]. Furthermore, the pattern of recurrence, including time to recurrence and location of the recurrent tumor, seems to be correlated with the MGMT methylation status of the primary tumor [87].

Hypermethylation phenotype

A subset of glioblastoma tumors has been found to contain a hypermethylation phenotype at a large number of CpG islands; this has been named the glioma-CpG island methylator phenotype (G-CIMP) by the TCGA. These G-CIMP tumors cluster into the aforementioned proneural subgroup, are strongly associated with IDH1 mutations, and generally affect younger patients with improved prognosis [88]. Furthermore, inhibition of histone demethylases and TET 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases by mutated IDH1 potentially implies the methylation of an even greater number of genes in this subgroup [48].

MicroRNAs

miRs are short non-coding RNAs, consisting of approximately 22 nucleotides, which regulate gene expression. miRs usually inhibit target genes’ expression, either by inhibiting translation or by triggering the cleavage of the target mRNA. Over 700 miRs have been described in humans [89]. By use of the same methods previously described for gene expression, differences in miR expression have been examined. Compared with normal brain tissue a variety of differentially expressed miRs have been found (Table 5) [90–101].

Table 5.

Frequently identified microRNA expression alterations in glioblastoma

| miRNA | Alteration of expression | Function of encoded protein | Targets | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-7 | Decreased | Increases apoptosis, decreases invasion | EGFR | [92, 97, 98] |

| miR-15 | Increased | Regulator of cell-cycle progression | CCNE1 | [93] |

| miR-21 | Increased | Oncomir, antiapoptosis | RECK, PDCD4, PTEN | [92, 93, 97] |

| miR-26 | Increased | Induces tumor growth, part of oncomir/oncogene cluster with CDK4 and CENTG1 | PTEN and PI3K/Akt pathway | [102] |

| miR-34 | Decreased | Inhibitor of proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion | TP53, c-Met, NOTCH1/2 | [99] |

| miR-124 | Decreased | Inhibitor of proliferation, cell differentiation | CDK6, PTBP, SCP1 | [97] |

| miR-125 | Increased | Inductor of proliferation and inhibitor of apoptosis | ERBB2, ERBB3, TP53 | [92] |

| miR-128 | Decreased | Inhibitor of proliferation | BMI1, E2F3a, EGFR | [92–94] |

| miR-137 | Decreased | Inhibitor of proliferation, cell differentiation | CDK6 | [97] |

| miR-155 | Increased | Regulator of immune response in cells | SMAD2 | [97] |

| miR-181 | Decreased | Reduced colony formation and migration | TCL1 | [92, 100] |

| miR-196 | Increased | Inductor of proliferation, cell differentiation | HOXB8, HMGA2, ANXA1 | [93] |

| miR-210 | Increased | Regulator of proliferation | FGFRL-1 | [97] |

| miR-221 | Increased | Cell proliferation | p27Kip1, p57Kip2 | [90, 92] |

| miR-222 | Increased | Cell proliferation | p27Kip1, p57Kip2 | [90] |

| miR-296 | Increased | Inductor of neovascularization | HGS | [91] |

| miR-326 | Decreased | Reduces cell viability and invasion | NOTCH1/2 | [101] |

| miR-451 | Increased | Inhibitor of migration, inductor of proliferation | CAB39 | [96] |

OncomiRs, tumor suppressor miRs, and therapeutic implications

Frequently up-regulated miRs are called oncomiRs. Of these, miR-26a is found to target PTEN in glioblastomas [102]. Furthermore, miR-26 cooperates with oncogenes CDK4 and CENTG1, forming an oncomiR/oncogene cluster, targeting the RB, PI3K/AKT, and JNK pathways and increasing aggressiveness in glioblastoma [95]. miR-221 and miR-222 are thought to target cell cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27 and p57 by targeting the pro-apoptotic PUMA [103]. In contrast with these oncomiRs, frequently down-regulated miRs in glioblastoma are considered tumor-suppressor miRs. Of these, miR-7 independently inhibits both the EGFR and AKT pathways [98]. miR-34a suppresses glioblastoma growth by targeting c-Met and Notch [99]. miR-124 and miR-137 target CDK6, which is important in the G1/S-phase transition [97]. miR-128 targets BMI1, which has been shown to promote stem cell renewal [94]. Downregulation of miR-181 is found in responders to temozolomide [100]. The delivery of underexpressed tumor-suppressor miRs may be an appealing approach for therapy. In contrast, overexpressed oncogenic miRNas may be targeted by antagomirs, because overexpression of the oncomiRs miR-26a, miR-196, and miR-451 has been correlated with poorer survival [93]. A recent review has provided an up-to-date overview on miRs and their inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment and readers should refer to this for more information [104].

Proteomics

Proteomic studies involve research on the final structure, function, and activity of proteins. Therefore, post-translational modifications on the transcript are included in the results. Thus far, only a limited number of proteomic studies have been performed on glioblastomas and there are still conceptual and technical limitations to overcome [105]. In general, samples are run on 2D gels, which show protein patterns on the basis of size and charge. Proteins identified in tumor samples but not in normal tissue samples are subsequently analyzed by mass spectrometry with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) [106]. Thus far, glioma subtypes have been distinguished on the basis of different protein patterns as primary and secondary glioblastomas [107, 108]. Furthermore, on the basis of proteome analysis, survival has been predicted in respect of glioma subtypes [107]. Additionally, proteins’ phosphorylation status is a tool with which to identify activated proteins. Consequently, activated receptor tyrosine kinases [109, 110] and the downstream signaling pathways of EGFRvIII have been identified in glioblastomas [111].

Other molecular aspects of glioblastomas

Molecular differences between primary and secondary glioblastomas

Primary and secondary glioblastoma subtypes are histopathologically indistinguishable, but differences can be demonstrated by molecular markers at the epigenetic [77], genetic [1, 18, 24], expression [65], and proteomic [108] levels (Fig. 2; Table 4). Primary glioblastomas have a greater prevalence of EGFR alterations, MDM2 duplications, PTEN mutations, and homozygous deletions of CDKN2A [1, 18]. MET amplification [24], overexpression of PDGFRA, and mutations in IDH1 and TP53 are more prevalent in secondary glioblastomas [1, 9, 18, 33, 39, 41, 43].

The sequential order of molecular alterations

Molecular alterations causing glioblastoma are thought to occur in a sequential order, implicating different stages of gliomagenesis (Fig. 2). For example, IDH1-inactivating mutations seem to be an early event in gliomagenesis [43]. In contrast, PTEN mutations and LOH 10q are thought to be important in glioma progression, but not initiation [18].

Potential therapeutic targets and future perspectives

Taking into consideration all the molecular alterations found in glioblastomas, it is clear that the picture of the changes in gliomablastoma becomes more complex as the techniques that enable us to investigate molecular mechanisms develop. The good news is, however, that many of the alterations identified in glioblastoma cluster in three pathways, the P53 (64–87%), RB (68–78%), and the PI3K/AKT (50%), downstream of the receptor tyrosine kinases (altered 88% in total; Fig. 1). Most alterations occur in a mutually exclusive fashion: alterations within one tumor affect only a single gene in a pathway, suggesting that different genes in a pathway are functionally equivalent [7–9, 71].

Quality of models

Functional validation of the identified molecular changes is essential before they can be assessed as targets for therapy. Taking this into account, it becomes clear that good models are needed for high-throughput testing of rationally designed combinations of drugs with specific targets. Several experiments have shown that established glioblastoma cell lines resemble those of the original glioblastomas very poorly when compared at the level of DNA alterations or gene expression profiles [71]. Tumor neurospheres cultured in stem cell medium, organotypic spheroid cultures, or low-passage monolayer cultures, resemble the original tumors better and may be better models for study of glioblastomas in vitro [112, 113].

Therapeutic options, multimodal therapy, and delivery options

For optimum application of the insights presented in this paper, stratified clinical trials are necessary to investigate the best treatment options for each common (group of) genetic alteration(s) in glioblastomas. Ultimately, this could lead to more individualized therapies. Rational drug design and rationally designed clinical trials to test these drugs are needed, because an almost infinite number of compounds is currently available, and these can be tested in limitless numbers of combinations. With genomics approaches, discoveries of common features of different types of tumor may lead to new therapeutic targets and drugs for other tumor types also. The discovery of overexpression of VEGFA and its correlation with poor prognosis in glioblastomas [59] led to trials with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab. It is currently being used to treat recurrent glioblastoma and phase III trials are being conducted [114, 115].

Rather than single-agent therapy, with which good responses have been obtained in the treatment of other types of cancer but which probably will not suffice in the treatment of glioblastoma, combination treatment is necessary. The clinical response of recurrent glioblastomas to EGFR inhibitors was found, in one study, to be associated with co-expression of EGFRvIII and PTEN [19] or pAkt [116], but not in combination with TMZ and RT for newly diagnosed glioblastomas [117] or in glioblastomas treated with erlotinib and TMZ [118]. PTEN-deficient glioblastoma patients could, for example, be treated with a cocktail of drugs consisting of an EGFR inhibitor and rapamycin [19], however the results are not yet impressive [119]. The response to TMZ and RT of patients for whom MGMT methylation is not observed may be improved by addition of MGMT-depleting agents, which are currently under investigation [120]. In this respect, the choice of anti-epileptic drug may become important as levetiracetam has been shown to inhibit MGMT expression in a preliminary study [121]. In addition, MGMT-mediated TMZ resistance may be overcome by more frequent temozolomide doses in dose-dense schedules [122]. Thus far, the results are disappointing, and a putative disadvantage of combination treatment is the potential increase in side effects [123]. This may, in part, be solved by application of new drug-delivery techniques. In this field, advances have been made with the application of biodegradable wafers, convection-enhanced delivery, and strategically-designed liposomes which circumvent the blood–brain barrier [124, 125]. Recent reviews have provided up-to date overviews on therapy, and we refer the reader to those for more details on ongoing and future therapeutic trials [126].

Synopsis

To summarize, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying subgroups of glioblastoma patients has increased. Moreover, many of the alterations in the aforementioned pathways have been elucidated, and molecular typing of glioblastomas on the basis of gene expression has been used to predict prognosis. Furthermore, for the first time it has been shown that the effects of treatment are distinctly different for different molecular types of glioblastoma classified on this basis [71]. In contrast with many other forms of cancer, however, subsequent application of these results to treatment is lagging behind. Nevertheless, assessment of the molecular profiles of responding versus non-responding patients can be used to determine predictive factors and biomarkers, and may lead to identification of new therapeutic targets. Validation of such new therapeutic approaches will be followed by stratified clinical trials based on such molecular subgroups. Finally, current insights will ultimately lead to more individualized therapy for glioblastoma patients. Combination of current knowledge of molecular alterations in glioblastoma with the availability of many drugs with specific targets makes investigation of new treatments more promising than ever before.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Ron van Noorden and Professor Peter Vandertop for their helpful suggestions and critical reading of earlier versions of this manuscript, Professor Dirk Troost for providing the histological images, Rob Kreuger for creating the illustrations, and Rene Spijker for helping with the search strategy.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1445–1453. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Mirimanoff RO. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krex D, Klink B, Hartmann C, von Deimling A, Pietsch T, Simon M, Sabel M, Steinbach JP, Heese O, Reifenberger G, Weller M, Schackert G. Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton EC, Lamborn KR, Feuerstein BG, Prados M, Scott J, Forsyth P, Passe S, Jenkins RB, Aldape KD. Genetic aberrations defined by comparative genomic hybridization distinguish long-term from typical survivors of glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6205–6210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorlia T, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, Mirimanoff RO, Weller M, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Stupp R. Nomograms for predicting survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: prognostic factor analysis of EORTC and NCIC trial 26981–22981/CE.3. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.TCGAN Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin D, Ogawa S, Kawamata N, Tunici P, Finocchiaro G, Eoli M, Ruckert C, Huynh T, Liu G, Kato M, Sanada M, Jauch A, Dugas M, Black KL, Koeffler HP. High-resolution genomic copy number profiling of glioblastoma multiforme by single nucleotide polymorphism DNA microarray. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:665–677. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA, Jr, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SK, Shinjo SM, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigner SH, Bjerkvig R, Laerum OD. DNA content and chromosomal composition of malignant human gliomas. Neurol Clin. 1985;3:769–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell JA, Johnson SP, McLendon RE, Lister DW, Horne KS, Rasheed A, Quinn JA, Ali-Osman F, Friedman AH, Modrich PL, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. Mismatch repair deficiency does not mediate clinical resistance to temozolomide in malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4859–4868. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter C, Smith R, Cahill DP, Stephens P, Stevens C, Teague J, Greenman C, Edkins S, Bignell G, Davies H, O’Meara S, Parker A, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Brackenbury L, Buck G, Butler A, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gorton M, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Kosmidou V, Laman R, Lugg R, Menzies A, Perry J, Petty R, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Solomon H, Tofts C, Varian J, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Easton DF, Riggins G, Roy JE, Levine KK, Mueller W, Batchelor TT, Louis DN, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Wooster R. A hypermutation phenotype and somatic MSH6 mutations in recurrent human malignant gliomas after alkylator chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3987–3991. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlback HS, Brandal P, Meling TR, Gorunova L, Scheie D, Heim S. Genomic aberrations in 80 cases of primary glioblastoma multiforme: pathogenetic heterogeneity and putative cytogenetic pathways. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:908–924. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiedemeyer R, Brennan C, Heffernan TP, Xiao Y, Mahoney J, Protopopov A, Zheng H, Bignell G, Furnari F, Cavenee WK, Hahn WC, Ichimura K, Collins VP, Chu GC, Stratton MR, Ligon KL, Futreal PA, Chin L. Feedback circuit among INK4 tumor suppressors constrains human glioblastoma development. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, Alexander S, Du J, Kau T, Thomas RK, Shah K, Soto H, Perner S, Prensner J, Debiasi RM, Demichelis F, Hatton C, Rubin MA, Garraway LA, Nelson SF, Liau L, Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Meyerson M, Golub TA, Lander ES, Mellinghoff IK, Sellers WR. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulholland PJ, Fiegler H, Mazzanti C, Gorman P, Sasieni P, Adams J, Jones TA, Babbage JW, Vatcheva R, Ichimura K, East P, Poullikas C, Collins VP, Carter NP, Tomlinson IP, Sheer D. Genomic profiling identifies discrete deletions associated with translocations in glioblastoma multiforme. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:783–791. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.7.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, Di Patre PL, Burkhard C, Schuler D, Probst-Hensch NM, Maiorka PC, Baeza N, Pisani P, Yonekawa Y, Yasargil MG, Lutolf UM, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6892–6899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, Haas-Kogan DA, Zhu S, Dia EQ, Lu KV, Yoshimoto K, Huang JH, Chute DJ, Riggs BL, Horvath S, Liau LM, Cavenee WK, Rao PN, Beroukhim R, Peck TC, Lee JC, Sellers WR, Stokoe D, Prados M, Cloughesy TF, Sawyers CL, Mischel PS. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, Misra A, Nigro JM, Colman H, Soroceanu L, Williams PM, Modrusan Z, Feuerstein BG, Aldape K. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelloski CE, Lin E, Zhang L, Yung WK, Colman H, Liu JL, Woo SY, Heimberger AB, Suki D, Prados M, Chang S, Barker FG, III, Fuller GN, Aldape KD. Prognostic associations of activated mitogen-activated protein kinase and Akt pathways in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3935–3941. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Gines C, Gil-Benso R, Ferrer-Luna R, Benito R, Serna E, Gonzalez-Darder J, Quilis V, Monleon D, Celda B, Cerda-Nicolas M. New pattern of EGFR amplification in glioblastoma and the relationship of gene copy number with gene expression profile. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:856–865. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weller M, Felsberg J, Hartmann C, Berger H, Steinbach JP, Schramm J, Westphal M, Schackert G, Simon M, Tonn JC, Heese O, Krex D, Nikkhah G, Pietsch T, Wiestler O, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Loeffler M. Molecular predictors of progression-free and overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a prospective translational study of the German Glioma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5743–5750. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maher EA, Brennan C, Wen PY, Durso L, Ligon KL, Richardson A, Khatry D, Feng B, Sinha R, Louis DN, Quackenbush J, Black PM, Chin L, DePinho RA. Marked genomic differences characterize primary and secondary glioblastoma subtypes and identify two distinct molecular and clinical secondary glioblastoma entities. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11502–11513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holtkamp N, Ziegenhagen N, Malzer E, Hartmann C, Giese A, von Deimling A. Characterization of the amplicon on chromosomal segment 4q12 in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:291–297. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichimura K, Vogazianou AP, Liu L, Pearson DM, Backlund LM, Plant K, Baird K, Langford CF, Gregory SG, Collins VP. 1p36 is a preferential target of chromosome 1 deletions in astrocytic tumours and homozygously deleted in a subset of glioblastomas. Oncogene. 2008;27:2097–2108. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav AK, Renfrow JJ, Scholtens DM, Xie H, Duran GE, Bredel C, Vogel H, Chandler JP, Chakravarti A, Robe PA, Das S, Scheck AC, Kessler JA, Soares MB, Sikic BI, Harsh GR, Bredel M. Monosomy of chromosome 10 associated with dysregulation of epidermal growth factor signaling in glioblastomas. JAMA. 2009;302:276–289. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bredel M, Scholtens DM, Yadav AK, Alvarez AA, Renfrow JJ, Chandler JP, Yu IL, Carro MS, Dai F, Tagge MJ, Ferrarese R, Bredel C, Phillips HS, Lukac PJ, Robe PA, Weyerbrock A, Vogel H, Dubner S, Mobley B, He X, Scheck AC, Sikic BI, Aldape KD, Chakravarti A, Harsh GRt. NFKBIA deletion in glioblastomas. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:627–637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veeriah S, Brennan C, Meng S, Singh B, Fagin JA, Solit DB, Paty PB, Rohle D, Vivanco I, Chmielecki J, Pao W, Ladanyi M, Gerald WL, Liau L, Cloughesy TC, Mischel PS, Sander C, Taylor B, Schultz N, Major J, Heguy A, Fang F, Mellinghoff IK, Chan TAC. The tyrosine phosphatase PTPRD is a tumor suppressor that is frequently inactivated and mutated in glioblastoma and other human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9435–9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900571106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura M, Yang F, Fujisawa H, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 19 in secondary glioblastomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:539–543. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Sausen M, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Rodriguez FJ, Cahill DP, McLendon R, Riggins G, Velculescu VE, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SK, Vogelstein B, Bigner D, Yan H, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW. Mutations in CIC and FUBP1 contribute to human oligodendroglioma. Science. 2011;333:1453–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.1210557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenkins RB, Blair H, Ballman KV, Giannini C, Arusell RM, Law M, Flynn H, Passe S, Felten S, Brown PD, Shaw EG, Buckner JC. A t(1;19)(q10;p10) mediates the combined deletions of 1p and 19q and predicts a better prognosis of patients with oligodendroglioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9852–9861. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, Kimmelman AC, Hiller DJ, Chen AJ, Perry SR, Tonon G, Chu GC, Ding Z, Stommel JM, Dunn KL, Wiedemeyer R, You MJ, Brennan C, Wang YA, Ligon KL, Wong WH, Chin L, DePinho RA. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature07443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeifer GP, Hainaut P. Next-generation sequencing: emerging lessons on the origins of human cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:62–68. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283414d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekstrand AJ, Sugawa N, James CD, Collins VP. Amplified and rearranged epidermal growth factor receptor genes in human glioblastomas reveal deletions of sequences encoding portions of the N- and/or C-terminal tails. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4309–4313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JC, Vivanco I, Beroukhim R, Huang JH, Feng WL, DeBiasi RM, Yoshimoto K, King JC, Nghiemphu P, Yuza Y, Xu Q, Greulich H, Thomas RK, Paez JG, Peck TC, Linhart DJ, Glatt KA, Getz G, Onofrio R, Ziaugra L, Levine RL, Gabriel S, Kawaguchi T, O’Neill K, Khan H, Liau LM, Nelson SF, Rao PN, Mischel P, Pieper RO, Cloughesy T, Leahy DJ, Sellers WR, Sawyers CL, Meyerson M, Mellinghoff IK. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation in glioblastoma through novel missense mutations in the extracellular domain. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knobbe CB, Reifenberger J, Reifenberger G. Mutation analysis of the Ras pathway genes NRAS, HRAS, KRAS and BRAF in glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:467–470. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0929-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, Edkins S, O’Meara S, Vastrik I, Schmidt EE, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Bhamra G, Buck G, Choudhury B, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Perry J, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Tofts C, Varian J, Webb T, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Cahill DP, Louis DN, Goldstraw P, Nicholson AG, Brasseur F, Looijenga L, Weber BL, Chiew YE, DeFazio A, Greaves MF, Green AR, Campbell P, Birney E, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, Tan MH, Khoo SK, Teh BT, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Wooster R, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleeker FE, Lamba S, Leenstra S, Troost D, Hulsebos T, Vandertop WP, Frattini M, Molinari F, Knowles M, Cerrato A, Rodolfo M, Scarpa A, Felicioni L, Buttitta F, Malatesta S, Marchetti A, Bardelli A. IDH1 mutations at residue p.R132 (IDH1(R132)) occur frequently in high-grade gliomas but not in other solid tumors. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:7–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, Idbaih A, Laffaire J, Ducray F, El Hallani S, Boisselier B, Mokhtari K, Hoang-Xuan K, Delattre JY. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4150–4154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichimura K, Pearson DM, Kocialkowski S, Backlund LM, Chan R, Jones DT, Collins VPC. IDH1 mutations are present in the majority of common adult gliomas but rare in primary glioblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:341–347. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, Korshunov A, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ, Friedman H, Friedman A, Reardon D, Herndon J, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Bigner DD. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bleeker FE, Atai NA, Lamba S, Jonker A, Rijkeboer D, Bosch KS, Tigchelaar W, Troost D, Vandertop WP, Bardelli A, Van Noorden CJ. The prognostic IDH1(R132) mutation is associated with reduced NADP+-dependent IDH activity in glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:487–494. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0645-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, Jiang W, Zha Z, Wang P, Yu W, Li Z, Gong L, Peng Y, Ding J, Lei Q, Guan KL, Xiong Y. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 2009;324:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1170944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, Marks KM, Prins RM, Ward PS, Yen KE, Liau LM, Rabinowitz JD, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Vander Heiden MG, Su SMC. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, Ito S, Yang C, Xiao MT, Liu LX, Jiang WQ, Liu J, Zhang JY, Wang B, Frye S, Zhang Y, Xu YH, Lei QY, Guan KL, Zhao SM, Xiong Y. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe T, Nobusawa S, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations are early events in the development of astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1149–1153. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheurer ME, Etzel CJ, Liu M, El-Zein R, Airewele GE, Malmer B, Aldape KD, Weinberg JS, Yung WK, Bondy ML. Aggregation of cancer in first-degree relatives of patients with glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2491–2495. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartzbaum JA, Xiao Y, Liu Y, Tsavachidis S, Berger MS, Bondy ML, Chang JS, Chang SM, Decker PA, Ding B, Hepworth SJ, Houlston RS, Hosking FJ, Jenkins RB, Kosel ML, McCoy LS, McKinney PA, Muir K, Patoka JS, Prados M, Rice T, Robertson LB, Schoemaker MJ, Shete S, Swerdlow AJ, Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Yang P, Wrensch MRC. Inherited variation in immune genes and pathways and glioblastoma risk. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1770–1777. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Hallani S, Marie Y, Idbaih A, Rodero M, Boisselier B, Laigle-Donadey F, Ducray F, Delattre JY, Sanson M. No association of MDM2 SNP309 with risk of glioblastoma and prognosis. J Neurooncol. 2007;85:241–244. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB, Dobbins SE, Sanson M, Malmer B, Simon M, Marie Y, Boisselier B, Delattre JY, Hoang-Xuan K, El Hallani S, Idbaih A, Zelenika D, Andersson U, Henriksson R, Bergenheim AT, Feychting M, Lonn S, Ahlbom A, Schramm J, Linnebank M, Hemminki K, Kumar R, Hepworth SJ, Price A, Armstrong G, Liu Y, Gu X, Yu R, Lau C, Schoemaker M, Muir K, Swerdlow A, Lathrop M, Bondy M, Houlston RS. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:899–904. doi: 10.1038/ng.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wrensch M, Jenkins RB, Chang JS, Yeh RF, Xiao Y, Decker PA, Ballman KV, Berger M, Buckner JC, Chang S, Giannini C, Halder C, Kollmeyer TM, Kosel ML, LaChance DH, McCoy L, O’Neill BP, Patoka J, Pico AR, Prados M, Quesenberry C, Rice T, Rynearson AL, Smirnov I, Tihan T, Wiemels J, Yang P, Wiencke JKC. Variants in the CDKN2B and RTEL1 regions are associated with high-grade glioma susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:905–908. doi: 10.1038/ng.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y, Shete S, Etzel CJ, Scheurer M, Alexiou G, Armstrong G, Tsavachidis S, Liang FW, Gilbert M, Aldape K, Armstrong T, Houlston R, Hosking F, Robertson L, Xiao Y, Wiencke J, Wrensch M, Andersson U, Melin BS, Bondy MC. Polymorphisms of LIG4, BTBD2, HMGA2, and RTEL1 genes involved in the double-strand break repair pathway predict glioblastoma survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2467–2474. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.IHGSC Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lal A, Lash AE, Altschul SF, Velculescu V, Zhang L, McLendon RE, Marra MA, Prange C, Morin PJ, Polyak K, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Strausberg RL, Riggins GJ. A public database for gene expression in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5403–5407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santosh V, Arivazhagan A, Sreekanthreddy P, Srinivasan H, Thota B, Srividya MR, Vrinda M, Sridevi S, Shailaja BC, Samuel C, Prasanna KV, Thennarasu K, Balasubramaniam A, Chandramouli BA, Hegde AS, Somasundaram K, Kondaiah P, Rao MR. Grade-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins-2, -3, and -5 in astrocytomas: IGFBP-3 emerges as a strong predictor of survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1399–1408. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Godard S, Getz G, Delorenzi M, Farmer P, Kobayashi H, Desbaillets I, Nozaki M, Diserens AC, Hamou MF, Dietrich PY, Regli L, Janzer RC, Bucher P, Stupp R, de Tribolet N, Domany E, Hegi ME. Classification of human astrocytic gliomas on the basis of gene expression: a correlated group of genes with angiogenic activity emerges as a strong predictor of subtypes. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6613–6625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nigro JM, Misra A, Zhang L, Smirnov I, Colman H, Griffin C, Ozburn N, Chen M, Pan E, Koul D, Yung WK, Feuerstein BG, Aldape KD. Integrated array-comparative genomic hybridization and expression array profiles identify clinically relevant molecular subtypes of glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1678–1686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hormigo A, Gu B, Karimi S, Riedel E, Panageas KS, Edgar MA, Tanwar MK, Rao JS, Fleisher M, DeAngelis LM, Holland EC. YKL-40 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 as potential serum biomarkers for patients with high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5698–5704. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tso CL, Shintaku P, Chen J, Liu Q, Liu J, Chen Z, Yoshimoto K, Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Liau LM, Nelson SF. Primary glioblastomas express mesenchymal stem-like properties. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:607–619. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee Y, Scheck AC, Cloughesy TF, Lai A, Dong J, Farooqi HK, Liau LM, Horvath S, Mischel PS, Nelson SF. Gene expression analysis of glioblastomas identifies the major molecular basis for the prognostic benefit of younger age. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:52. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mir SE, De Witt Hamer PC, Krawczyk PM, Balaj L, Claes A, Niers JM, Van Tilborg AA, Zwinderman AH, Geerts D, Kaspers GJ, Peter Vandertop W, Cloos J, Tannous BA, Wesseling P, Aten JA, Noske DP, Van Noorden CJ, Wurdinger T. In silico analysis of kinase expression identifies WEE1 as a gatekeeper against mitotic catastrophe in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tso CL, Freije WA, Day A, Chen Z, Merriman B, Perlina A, Lee Y, Dia EQ, Yoshimoto K, Mischel PS, Liau LM, Cloughesy TF, Nelson SF. Distinct transcription profiles of primary and secondary glioblastoma subgroups. Cancer Res. 2006;66:159–167. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vitucci M, Hayes DN, Miller CRC. Gene expression profiling of gliomas: merging genomic and histopathological classification for personalised therapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:545–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gravendeel LA, Kouwenhoven MC, Gevaert O, de Rooi JJ, Stubbs AP, Duijm JE, Daemen A, Bleeker FE, Bralten LB, Kloosterhof NK, De Moor B, Eilers PH, van der Spek PJ, Kros JM, Sillevis Smitt PA, van den Bent MJ, French PJ. Intrinsic gene expression profiles of gliomas are a better predictor of survival than histology. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9065–9072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li A, Walling J, Ahn S, Kotliarov Y, Su Q, Quezado M, Oberholtzer JC, Park J, Zenklusen JC, Fine HAC. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomic profiles reveals six glioma subtypes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2091–2099. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bredel M, Scholtens DM, Harsh GR, Bredel C, Chandler JP, Renfrow JJ, Yadav AK, Vogel H, Scheck AC, Tibshirani R, Sikic BI. A network model of a cooperative genetic landscape in brain tumors. JAMA. 2009;302:261–275. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Tayrac M, Aubry M, Saikali S, Etcheverry A, Surbled C, Guenot F, Galibert MD, Hamlat A, Lesimple T, Quillien V, Menei P, Mosser J. A 4-gene signature associated with clinical outcome in high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:317–327. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, Alexe G, Lawrence M, O’Kelly M, Tamayo P, Weir BA, Gabriel S, Winckler W, Gupta S, Jakkula L, Feiler HS, Hodgson JG, James CD, Sarkaria JN, Brennan C, Kahn A, Spellman PT, Wilson RK, Speed TP, Gray JW, Meyerson M, Getz G, Perou CM, Hayes DNC. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cadieux B, Ching TT, VandenBerg SR, Costello JF. Genome-wide hypomethylation in human glioblastomas associated with specific copy number alteration, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase allele status, and increased proliferation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8469–8476. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagarajan RP, Costello JF. Epigenetic mechanisms in glioblastoma multiforme. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez R, Esteller M. The DNA methylome of glioblastoma multiforme. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakamura M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Promoter hypermethylation of the RB1 gene in glioblastomas. Lab Invest. 2001;81:77–82. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakamura M, Ishida E, Shimada K, Kishi M, Nakase H, Sakaki T, Konishi N. Frequent LOH on 22q12.3 and TIMP-3 inactivation occur in the progression to secondary glioblastomas. Lab Invest. 2005;85:165–175. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wiencke JK, Zheng S, Jelluma N, Tihan T, Vandenberg S, Tamguney T, Baumber R, Parsons R, Lamborn KR, Berger MS, Wrensch MR, Haas-Kogan DA, Stokoe D. Methylation of the PTEN promoter defines low-grade gliomas and secondary glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:271–279. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Etcheverry A, Aubry M, de Tayrac M, Vauleon E, Boniface R, Guenot F, Saikali S, Hamlat A, Riffaud L, Menei P, Quillien V, Mosser JC. DNA methylation in glioblastoma: impact on gene expression and clinical outcome. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:701. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martinez R, Setien F, Voelter C, Casado S, Quesada MP, Schackert G, Esteller M. CpG island promoter hypermethylation of the pro-apoptotic gene caspase-8 is a common hallmark of relapsed glioblastoma multiforme. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1264–1268. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, Kros JM, Hainfellner JA, Mason W, Mariani L, Bromberg JE, Hau P, Mirimanoff RO, Cairncross JG, Janzer RC, Stupp R. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eoli M, Menghi F, Bruzzone MG, De Simone T, Valletta L, Pollo B, Bissola L, Silvani A, Bianchessi D, D’Incerti L, Filippini G, Broggi G, Boiardi A, Finocchiaro G. Methylation of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and loss of heterozygosity on 19q and/or 17p are overlapping features of secondary glioblastomas with prolonged survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2606–2613. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zawlik I, Vaccarella S, Kita D, Mittelbronn M, Franceschi S, Ohgaki H. Promoter methylation and polymorphisms of the MGMT gene in glioblastomas: a population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32:21–29. doi: 10.1159/000170088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Christmann M, Nagel G, Horn S, Krahn U, Wiewrodt D, Sommer C, Kaina B. MGMT activity, promoter methylation and immunohistochemistry of pretreatment and recurrent malignant gliomas: a comparative study on astrocytoma and glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2106–2118. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brell M, Ibanez J, Tortosa AC. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protein expression by immunohistochemistry in brain and non-brain systemic tumours: systematic review and meta-analysis of correlation with methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, Sotti G, Frezza G, Amista P, Morandi L, Spagnolli F, Ermani M. Recurrence pattern after temozolomide concomitant with and adjuvant to radiotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma: correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. J Clin Oncol. 2009;8:1275–1279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Blatt V, Pession A, Tallini G, Bertorelle R, Bartolini S, Calbucci F, Andreoli A, Frezza G, Leonardi M, Spagnolli F, Ermani M. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2192–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, Pan F, Pelloski CE, Sulman EP, Bhat KP, Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Hayes DN, Perou CM, Schmidt HK, Ding L, Wilson RK, Van Den Berg D, Shen H, Bengtsson H, Neuvial P, Cope LM, Buckley J, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Laird PW, Aldape KC. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.le Sage C, Nagel R, Egan DA, Schrier M, Mesman E, Mangiola A, Anile C, Maira G, Mercatelli N, Ciafre SA, Farace MG, Agami RC. Regulation of the p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2007;26:3699–3708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wurdinger T, Tannous BA, Saydam O, Skog J, Grau S, Soutschek J, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Krichevsky AMC. miR-296 regulates growth factor receptor overexpression in angiogenic endothelial cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ciafre SA, Galardi S, Mangiola A, Ferracin M, Liu CG, Sabatino G, Negrini M, Maira G, Croce CM, Farace MG. Extensive modulation of a set of microRNAs in primary glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guan Y, Mizoguchi M, Yoshimoto K, Hata N, Shono T, Suzuki SO, Araki Y, Kuga D, Nakamizo A, Amano T, Ma X, Hayashi K, Sasaki T. MiRNA-196 is upregulated in glioblastoma but not in anaplastic astrocytoma and has prognostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4289–4297. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, Williams S, Otsuki A, Nuovo G, Raychaudhury A, Newton HB, Chiocca EA, Lawler S. Targeting of the Bmi-1 oncogene/stem cell renewal factor by microRNA-128 inhibits glioma proliferation and self-renewal. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9125–9130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim H, Huang W, Jiang X, Pennicooke B, Park PJ, Johnson MDC. Integrative genome analysis reveals an oncomir/oncogene cluster regulating glioblastoma survivorship. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2183–2188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909896107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, Nuovo G, Palatini J, De Lay M, Van Brocklyn J, Ostrowski MC, Chiocca EA, Lawler SE. MicroRNA-451 regulates LKB1/AMPK signaling and allows adaptation to metabolic stress in glioma cells. Mol Cell. 2010;37:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]