Abstract

The site 1 protease, encoded by Mbtps1, mediates the initial cleavage of site 2 protease substrates, including sterol regulatory element binding proteins and CREB/ATF transcription factors. We demonstrate that a hypomorphic mutation of Mbtps1 called woodrat (wrt) caused hypocholesterolemia, as well as progressive hypopigmentation of the coat, that appears to be mechanistically unrelated. Hypopigmentation was rescued by transgenic expression of wild-type Mbtps1, and reciprocal grafting studies showed that normal pigmentation depended upon both cell-intrinsic or paracrine factors, as well as factors that act systemically, both of which are lacking in wrt homozygotes. Mbtps1 exhibited a maternal-zygotic effect characterized by fully penetrant embryonic lethality of maternal-zygotic wrt mutant offspring and partial embryonic lethality (~40%) of zygotic wrt mutant offspring. Mbtps1 is one of two maternal-zygotic effect genes identified in mammals to date. It functions nonredundantly in pigmentation and embryogenesis.

Keywords: pigmentation, coat color, site 1 protease, cholesterol, maternal-zygotic effect lethality

The site 1 protease (S1P), a transmembrane serine protease also known as subtilisin-kexin-isoenzyme 1, operates within the Golgi apparatus, where it performs the initial extracytoplasmic cleavage of site 2 protease (S2P) substrates during regulated intramembrane proteolysis, a process by which transmembrane proteins are cleaved within a membrane-spanning helix to release cytosolic domains (Ehrmann and Clausen 2004). S1P cleaves the sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) to regulate cholesterol homeostasis; CREB/ATF transcription factors ATF6 (Ye et al. 2000), CREBH (Zhang et al. 2006), CREB4 (Stirling and O’hare 2006), OASIS (Murakami et al. 2006), and Luman (Raggo et al. 2002) in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress; and the surface glycoprotein precursors of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, Lassa fever virus, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (Beyer et al. 2003; Kunz et al. 2003; Lenz et al. 2001; Vincent et al. 2003).

In the mouse, targeted disruption of the S1P-encoding gene Mbtps1 prevented normal epiblast formation and subsequent implantation of the embryo (Mitchell et al. 2001), resulting in lethality at an early developmental stage (Yang et al. 2001). Liver-specific knockout of Mbtps1 yielded viable mice in which blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels and the expression of genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) clearance were affected (Yang et al. 2001). Cartilage-specific Mbtps1-deficient mice died shortly after birth, exhibiting severe chondrodysplasia caused by the retention of type 2 collagen in the ER (Patra et al. 2007).

We recently generated a viable hypomorphic allele of Mbtps1, called woodrat, with the substitution Y496C in the extracellular domain. Homozygosity for the woodrat mutation caused hypersensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate−induced colitis by impairing the unfolded protein response in intestinal epithelial cells (Brandl et al. 2009) and conferred resistance to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus through an effect on dendritic cells (Popkin et al. 2011). We demonstrate here that cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic functions of S1P are required for normal coat color. In addition, the wrt mutation of Mbtps1 causes maternal-zygotic effect embryonic lethality.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions in The Scripps Research Institute Vivarium under the supervision of the Department of Animal Resources. Animals were fed a normal (Teklad #7012; Harlan) or a 5% cholesterol-enriched diet (TD00337; Harlan). All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. Tyrc-ghost mutant mice were produced and maintained in the Beutler lab. The Mbtps1wrt/wrt strain was generated by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis of C57BL/6J mice (Brandl et al. 2009) and maintained by breeding Mbtps1wrt/wrt males to Mbtps1wrt/+ females. The Tyrc-ghost and Mbtps1wrt strains are described at http://mutagenetix.utsouthwestern.edu.

For phenotypic rescue experiments, a BAC (CH29-174A18) containing the wild-type allele of Mbtps1 derived from the NOD/LtJ strain was injected into the male pronucleus of fertilized oocytes from matings of C57BL/6J females and Mbtps1wrt/wrt males. The limits of the genomic DNA sequence included in the BAC are 8:121841017−122109039. The expression of the transgenic wild-type Mbtps1 allele in mice was confirmed by detection via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of a GATA simple sequence length polymorphism present in the BAC and informative for C57BL/6J vs. NOD/LtJ strains using the following primers: 5′-CCAGCGGTTAATGGCATCTGAAATG-3′ and 5′-ATTGTCCTAAGCTGGGTGGCAGAG-3′.

Real-time PCR analysis

RNA from skin was isolated using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). DNAse-treated RNA underwent randomly primed cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR analysis. SYBR Green-based real-time PCR was performed using the DyNAmo SYBR Green qPCR Kit (Finnzymes). Mitf-specific primers were obtained from QIAGEN, and signals were normalized to β-actin. Normalized data were used to quantitate relative levels of Mitf using ΔΔCt analysis.

Skin grafts

Recipient mice were anesthetized and the flank hair shaved with electronic clippers. A graft bed was prepared on the lateral thoracic region under aseptic conditions. The graft bed was prepared by carefully removing the epidermis and dermis to the level of the panniculus carnosus without disturbing the vascular bed. Donor thoracic skin was prepared in the same manner, i.e., removing the epidermis and dermis and placing in a sterile Petri dish wetted with phosphate-buffered saline. The donor skin was then placed into the recipient vascular bed and a 1- to 2-mm margin left on all sides. The grafted skin was covered with sterile, antibiotic (bacitracin)-impregnated Vaseline gauze, covered with a bandage, and then wrapped in cloth tape. The grafts were left undisturbed for 7 days. On day 7, the bandages were removed, and the grafts were photographed on a daily basis.

Cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and very high-density lipoprotein cholesterol measurement

Four mice per genotype were fasted for 4 hr before blood collection from the retro-orbital sinus. Serum concentrations of total cholesterol and triglycerides were determined enzymatically on a Cobas Mira Plus autoanalyzer using the cholesterol R1 and triglycerides reagent methods, respectively (Roche Diagnostics). Colorimetric changes were measured at 500 nm. Lipoprotein-associated cholesterol was separated using the SPIFE 3000 agarose electrophoresis system (Helena Labs, Beaumont, TX) (Contois et al. 1999) and verified by fast-protein liquid chromatography with a Superose 6HR column and in-line post column analysis as described previously (Kieft et al. 1991).

Analysis of SREBP1 and SREBP2 processing

For SREBP analysis, livers were collected from mice fasted for 4 hr and homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem tissue grinder in a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 1 mM EDTA and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Biochemicals). The cell membrane-containing pellet obtained by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4° was vortexed at 4° in a second buffer made of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Biochemicals). The supernatant obtained from a 5-min centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4° was resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (0.5 M dithiothreitol, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 M Tris, pH 6.8, 50% glycerol, 0.2% bromophenol blue powder). Proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking in 5% skim milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline, membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-SREBP1 or anti-SREBP2 primary antibodies (Affinity BioReagents), followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody coupled to peroxidase (Rockland). Blots were stained with Rouge Ponceau (Sigma-Aldrich) and then developed by enhanced chemiluminescence using Super Signal West Pico ECL Substrate (Pierce); signals were recorded on autoradiographic film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Precursors SREBPs (~120 kD) were distinguished from processed SREBPs by size (~78 kD).

Statistical analysis

The significance of the outcomes of crosses was calculated using the χ2 test on the basis of the expected frequencies of hypopigmented (Mbtps1wrt/wrt) and normal (Mbtps1+/+ and /or Mbtps1wrt/+) progeny from a given cross, unless otherwise specified. The statistical significance of all other differences was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences with a P value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All error bars represent SD.

Results

S1P is required for normal coat color

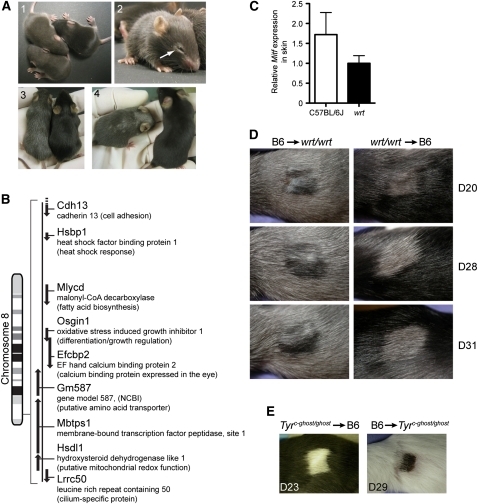

The recessive woodrat (wrt) mutation was isolated by positional cloning based on a hypopigmentation phenotype (Brandl et al. 2009). Mild uniform hypopigmentation was first observed in Mbtps1wrt/wrt homozygotes at 8 days of age (Figure 1A). Starting from a white ring around the eyes, the phenotype progressed irregularly to produce a coat composed of a combination of white and black hairs. In adults, the phenotype stabilized as a homogenous coat consisting of hairs with alternately normal or absent pigmentation.

Figure 1.

The woodrat mutation affects coat color in both a cell-autonomous and systemic manner. (A) The woodrat coat color phenotype at 8 days (1), 15 days (2), 18 days (3), and 6 weeks of age (4). (B) Chromosome 8 genes encompassed by the BAC used for transgenesis. (C) Relative expression of Mitf mRNA measured in the skin of wild type and Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice by reverse transcription PCR. (D) Skin grafted from a C57BL/6J (B6) mouse onto a Mbtps1wrt/wrt mouse and from a Mbtps1wrt/wrt mouse onto a C57BL/6J mouse on the days indicated posttransplantation. Results are representative of 3 (wrt/wrt→C57BL/6J) transplants and 3 (C57BL/6J→wrt/wrt) transplants. (E) Skin grafted from a Tyrc-ghost homozygous mutant mouse onto a wild-type C57BL/6J mouse and from a wild-type C57BL/6J mouse onto a Tyrc-ghost homozygote.

To confirm that the Mbtps1wrt mutation was responsible for the observed progressive hypopigmentation, we tested whether the phenotype could be rescued by transgenic expression of wild-type Mbtps1 in homozygous woodrat mice. A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing a segment of chromosome 8 genomic DNA encompassing the Mbtps1 locus (Figure 1B) was injected into the male pronucleus of fertilized C57BL/6J oocytes, from which 46 pups were born, seven of which carried the transgene. Genomic DNA from a Mbtps1wrt/wrt mouse was sequenced extensively over the region included within the BAC, so that 92.4% of all nucleotides comprising coding regions and splice junctions (defined as 10 bp at either end of each intron) were examined on at least one strand to a phred score of 30 or greater. No mutations other than the Mbtps1wrt allele were detected.

Two independent transgenic founders, both female heterozygotes, were crossed to male Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice and the heterozygous progeny were crossed to the parental Mbtps1wrt/wrt strain to achieve homozygosity for the wrt allele in a fraction of the offspring, 50% of which would be expected to inherit the transgene. Nine of them showed the hypopigmentation phenotype, all were homozygous for the wrt allele and none carried a transgene (P = 0.00195; exact binomial probability). Nineteen offspring carried a transgene, derived from one founder or the other, and all showed a wild-type coat color (P = 0.00000191; exact binomial probability). Combining these probabilities by Fisher’s method, the null hypothesis that the transgene does not affect the woodrat phenotype is rejected (χ2 on 4 df = 38.8; P < 0.0001).

Mitf is a key transcriptional regulator of melanocyte development, and several mutant alleles of Mitf, including mi-enu5, mi-bcc2 (Hansdottir et al. 2004), and mi-vit (Boissy et al. 1987; Lerner 1986), cause hypopigmentation similar in various aspects to that observed in wrt homozygotes. However, we found no significant difference between Mitf mRNA expression in the skin of wild-type vs. Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice (Figure 1C). Consistent with this finding, melanocytes of normal morphological appearance were present in the hair follicles of Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice; however, the functional status of those melanocytes was not evaluated. These findings suggest that the hypopigmentation of Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice is not caused by aberrant melanocyte development.

To determine whether the wrt pigmentation phenotype resulted from a systemic metabolic defect or from a defect localized to the skin, syngeneic skin transplants were performed (Figure 1D). Shaved dorsal skin from Mbtps1wrt/wrt or C57BL/6J mice was grafted onto C57BL/6J or Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice, respectively. In a wild-type C57BL/6J animal, Mbtps1wrt/wrt grafts retained their hypopigmented phenotype, whereas C57BL/6J skin transplanted onto a Mbtps1wrt/wrt individual acquired a hypopigmented phenotype. Control C57BL/6J skin grafts maintained their black color when transplanted onto a Tyrc-ghost homozygous mutant mouse, and reciprocal transplantation of skin from the Tyrc-ghost homozygous mutant onto wild-type recipients remained white (Figure 1E). These results indicate that normal pigmentation depends upon two independent processes, one systemic and one cell-autonomous or paracrine, both of which are disrupted by homozygosity for the Mbtps1wrt mutation.

Maternal-zygotic effect lethality caused by the woodrat mutation

Homozygosity for the wrt allele biases against survival in utero. Of 87 progeny in 23 litters born from crosses of Mbtps1wrt/wrt males to Mbtps1wrt/+ females, in which an equal number of homozygous and heterozygous progeny would be expected, 60 phenotypically normal and 27 phenotypically affected mice were produced (P = 0.0004). When fetuses from this cross were examined at 11 (n = 7 embryos, 1 litter), 14 (n = 6 embryos, 1 litter), 17 (n = 8 embryos, 1 litter), and 20 days of gestation (n = 6 embryos, 1 litter), 100% were found alive (Table 1), suggesting that death of homozygotes occurred before embryonic day 11. In independent crosses of heterozygotes, among 18 litters, 90 phenotypically normal and 17 phenotypically affected mice were produced (P = 0.0295). All litters were carefully counted on the day of birth, and no postnatal deaths were observed before genotyping at 19 days of age.

Table 1. Viability of embryos with the wrt mutation.

| Parents | Gestation Period (d) | Litters (no.) | Total Embryos (no.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | |||

| ♂Mbtpswrt/wrt × ♀Mbtpswrt/+ | 11 | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| 14 | 1 | 6 | 0 | |

| 17 | 1 | 8 | 0 | |

| 20 | 1 | 6 | 0 | |

| ♂Mbtpswrt/wrt × ♀Mbtpswrt/wrt | 0.5 | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

We also observed that no offspring were born from crosses of Mbtps1wrt/wrt males and Mbtps1wrt/wrt females; these female mice were surveyed daily from day 18 to day 24 after observation of the copulatory plug. Mbtps1wrt/wrt females crossed to Mbtps1wrt/+ males or Mbtps1+/+ males gave birth to heterozygous pups, but in the former cross, never to homozygous pups; litters were counted on the day of birth and deaths among pups were not observed before genotyping at postnatal day 19. However, as already noted, Mbtps1wrt/+ females crossed to Mbtps1wrt/wrt males produced both heterozygous and homozygous offspring. Thus, the wrt allele causes maternal-zygotic effect lethality in that homozygous females can only give birth to offspring carrying at least one wild-type copy of the Mbtps1 locus, but heterozygous females that carry one wild-type copy of Mbtps1 can give birth to offspring lacking wild type Mbtps1.

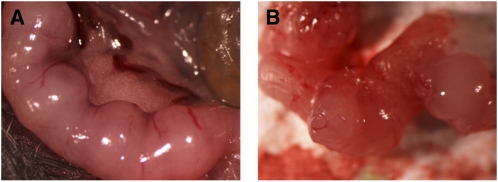

To determine the stage at which development of homozygous maternal-zygotic mutants fails, embryos from Mbtps1wrt/wrt females crossed to Mbtps1wrt/wrt males were examined after various gestation periods. Mbtps1wrt/wrt females crossed to Mbtps1wrt/wrt males appeared pregnant 8 days postcoitum and left and right uterine horns were highly vascularized and displayed rounded bulges (Figure 2A). However, no fetal bodies were found within their uteri at 8, 11, or 14 days of gestation (Figure 2B and Table 1). Thus, death and resorption of maternal-zygotic mutant embryos (homozygous wrt embryos derived from homozygous wrt mothers) occur before the eighth day of gestation.

Figure 2.

Embryonic lethality of homozygous maternal-zyogtic wrt mutants before 8 days of gestation. (A) The uterus of a pregnant Mbtps1wrt/wrt female mated to a Mbtps1wrt/wrt male on the eighth day of gestation appeared to contain embryos. (B) However, no fetal bodies were found inside it.

Low cholesterol levels in wrt homozygotes are not responsible for hypopigmentation

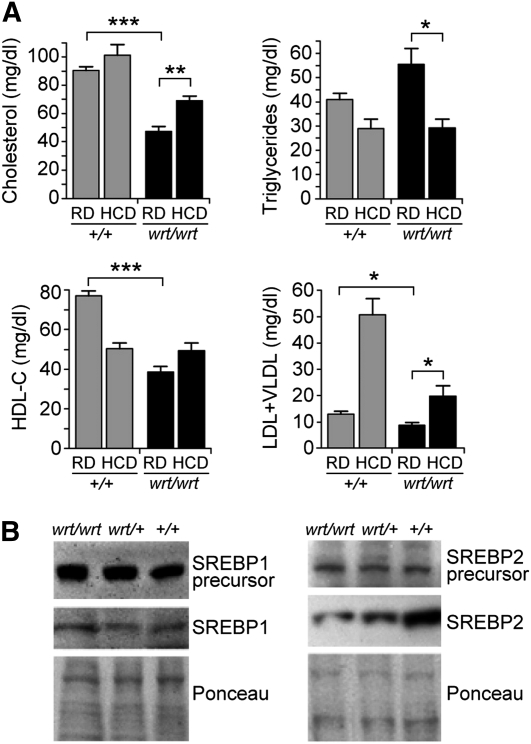

Because S1P has nonredundant functions in both cholesterol and triglyceride homeostasis through cleavage of SREBPs (Sakai et al. 1998), we measured the levels of cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein-C (LDL-C)/very low-density lipoprotein-C (VLDL-C) in Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice fasted for 4 hr (Figure 3A). Serum concentrations of cholesterol and lipoproteins were significantly reduced in homozygous mutant mice as compared to wild-type controls. Triglyceride levels were not affected by the wrt mutation. To determine whether a high-cholesterol diet could rescue the low levels of serum cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C/VLDL-C, as well as the pigmentation defect in wrt homozygotes, mice were fed a high-cholesterol diet and observed for 1 week. The high-cholesterol diet increased the concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL-C/VLDL-C in the serum of Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice relative to levels in Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice fed a regular diet (Figure 3A). However, the high-cholesterol diet did not change the abnormal coat pigmentation of Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice.

Figure 3.

Reduced serum cholesterol in Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice. (A) Cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-C, and LDL-C/VLDL-C concentrations in the serum of 8-week-old Mbtps1+/+ and Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice fed a regular diet (RD) or a diet supplemented with 5% cholesterol (HCD) for 1 week. Each bar represents the average for four mice. Error bars represent SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (B) SREBP1 and SREBP2 cleavage in Mbtps1wrt/wrt, Mbtps1wrt/+, and Mbtps1+/+ hepatocytes after 4 hr of fasting. Protein loading was assessed with Ponceau Red. Results are representative of four experiments for SREBP1 and three experiments for SREBP2, each using three mice per genotype.

There are three isoforms of SREBP. SREBP2 preferentially up-regulates the expression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis, whereas SREBP1c selectively induces lipogenic genes without affecting cholesterol synthesis genes (Eberle et al. 2004), and SREBP1a leads to accumulation of both cholesterol and triglycerides. We hypothesized that the disproportionate effect of the woodrat mutation on serum cholesterol vs. triglyceride concentration might reflect substrate specificity, i.e., more efficient regulated intramembrane proteolysis processing of SREBP1c relative to SREBP2 in Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed that whereas the SREBP1 precursor was equally processed into its 68 kD active form in hepatocytes from Mbtps1wrt/wrt, Mbtps1wrt/+, and wild-type mice, a reduced amount of precursor SREBP2 was processed into its cleaved, active form in Mbtps1wrt/wrt compared with Mbtps1wrt/+ or wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 3B).

Discussion

In previous studies, we established that a gene trap allele of Mbtps1 was lethal both in the homozygous state and in trans with Mbtps1wrt (Brandl et al. 2009). However, although hypopigmentation was the phenotype used to map the Mbtps1wrt mutation, no firm conclusion could be drawn concerning cause and effect. Using transgenesis, we have now adduced strong evidence that the previously reported coat color anomaly of the wrt strain does, in fact, result from the hypomorphic wrt mutation of Mbtps1. In a compound heterozygous cross, Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice that were also transgenic for the wild-type Mbtps1 locus never displayed hypopigmentation and all mice that did display hypopigmentation were of the Mbtps1wrt/wrt genotype, and lacked the transgene.

More than 300 gene products are known to affect mouse pigmentation (Montoliu et al. 2011), including proteins that regulate melanocyte proliferation and development (e.g., Mitf, Kit, Edn1), melanosome biogenesis (e.g., Oca2, Slc45a2, BLOC-1 complex), melanosome transport (e.g., Rab27a, melanophilin, myosin Va), and melanogenesis (e.g., Tyr, Dct, Mc1r). Most classical coat color genes encode factors produced in the skin and/or hair follicle that signal locally to melanocytes or within them (Hirobe 2011; Slominski et al. 2004). In general, less is known of factors that circulate through the bloodstream and exert systemic control over pigmentation. One well-studied example is α-melanocyte−signaling hormone, which is produced in humans by melanocytes and keratinocytes (Chakraborty et al. 1996; Rousseau et al. 2007; Wakamatsu et al. 1997) and in mice and humans by the pituitary gland (Hirobe et al. 2004; Krude et al. 1998; Pears et al. 1992), through cleavage of the precursor protein proopiomelanocortin. α-melanocyte−signaling hormone from either tissue source in humans, and from the pituitary gland via the bloodstream in mice, promotes the production of eumelanin by melanocytes. Other systemic factors influencing pigmentation include steroid hormones (e.g., estrogen, progesterone, androgen), fatty acids (e.g., linoleic acid, palmitic acid), and iron (Hirobe 2011).

Using reciprocal immunologically compatible skin grafts, we showed that normal pigmentation of the fur depends upon two processes, one cell-autonomous or paracrine and one systemic, both of which are disrupted by homozygosity for the wrt mutation. The effects of Mbtps1 activity on cells or tissues at remote locations may be interpreted in several ways. First, it has been noted that both an ER/Golgi membrane-anchored and a shed, soluble form of S1P exist, and the soluble form might conceivably exert a systemic effect on pigmentation. Second, it may be imagined that specific metabolites, dependent upon the enzymatic activity of S1P cleavage products, might be needed for this process. Although we showed that serum cholesterol levels were reduced in Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice, cholesterol does not seem to be the crucial metabolite needed for normal pigmentation, since a high cholesterol diet did not normalize the coat pigmentation of Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice.

In breeding experiments, maternal-zygotic Mbtps1wrt mutant offspring (homozygotes derived from homozygous mutant mothers) displayed fully penetrant embryonic lethality, whereas zygotic mutant offspring (homozygotes derived from heterozygous mothers) displayed partial (~40%) embryonic lethality, and heterozygous mutant offspring of homozygous mothers were fully viable. These findings demonstrate a maternal-zygotic effect of Mbtps1, to our knowledge the second mammalian gene to which such an effect has been ascribed. Mouse Zfp57 was the first identified mammalian maternal-zygotic effect gene and was found to participate in the maintenance of genomic DNA methylation imprints without which mouse embryos died in midgestation (Li et al. 2008). ZFP57, together with its cofactor KAP1, recruits DNA methyltransferases to a methylated hexanucleotide within numerous imprinting control regions (Quenneville et al. 2011; Zuo et al. 2011). A role for S1P in genomic imprinting remains to be tested.

Experiments in which Drosophila was used support an evolutionarily conserved requirement for the function of the S1P/S2P module during embryonic development. Analogously to wrt mutant mice, dS2P homozygous mutant fly embryos from heterozygous mothers emerged at a normal frequency, whereas less than 50% of the expected number of homozygous offspring derived from homozygous mothers survived (Matthews et al. 2009). The survival rate of heterozygous offspring of homozygous female flies was not reported in this study, leaving open the possibility that dS2P may function as a maternal-zygotic effect gene. However, in contrast to the nonredundant function of S1P in mice, the caspase drICE can partially compensate for dS2P deficiency in Drosophila, thus permitting a significant proportion of homozygous fly embryos derived from homozygous mothers to survive to adulthood (Amarneh et al. 2009). Notably, maternal effect embryonic lethality of homozygous mutant flies was completely rescued by supplementation of the embryo culture medium with fatty acids (Matthews et al. 2009). Fatty acids and/or cholesterol may likewise be critically lacking during development of Mbtps1wrt/wrt concepti in utero.

We found that cholesterol and lipoproteins were preferentially reduced relative to triglycerides in serum from Mbtps1wrt/wrt mice, an effect that we attribute to a more severe impairment of SREBP2 processing as compared with SREBP1 processing. Y496, the residue mutated in woodrat mice, may provide a contact critical for interaction with SREBP2.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Hoebe and M. Berger for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM067759 and Broad Agency Announcement Contract HHSN27220000038C. S.R. was supported by a Human Frontier Science Program long term fellowship.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: D. W. Threadgill

Literature Cited

- Amarneh B., Matthews K. A., Rawson R. B., 2009. Activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein by the caspase drice in drosophila larvae. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 9674–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer W. R., Popplau D., Garten W., von Laer D., Lenz O., 2003. Endoproteolytic processing of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein by the subtilase SKI-1/S1P. J. Virol. 77: 2866–2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy R. E., Moellmann G. E., Lerner A. B., 1987. Morphology of melanocytes in hair bulbs and eyes of vitiligo mice. Am. J. Pathol. 127: 380–388 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl K., Rutschmann S., Li X., Du X., Xiao N., et al. , 2009. Enhanced sensitivity to DSS colitis caused by a hypomorphic Mbtps1 mutation disrupting the ATF6-driven unfolded protein response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 3300–3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty A. K., Funasaka Y., Slominski A., Ermak G., Hwang J., et al. , 1996. Production and release of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) derived peptides by human melanocytes and keratinocytes in culture: Regulation by ultraviolet B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1313: 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contois J. H., Gillmor R. G., Moore R. E., Contois L. R., Macer J. L., et al. , 1999. Quantitative determination of cholesterol in lipoprotein fractions by electrophoresis. Clin. Chim. Acta 282: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle D., Hegarty B., Bossard P., Ferre P., Foufelle F., 2004. SREBP transcription factors: Master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie 86: 839–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann M., Clausen T., 2004. Proteolysis as a regulatory mechanism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 709–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansdottir A. G., Palsdottir K., Favor J., Neuhauser-Klaus A., Fuchs H., et al. , 2004. The novel mouse microphthalmia mutations mitfmi-enu5 and mitfmi-bcc2 produce dominant negative mitf proteins. Genomics 83: 932–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T., 2011. How are proliferation and differentiation of melanocytes regulated? Pigment Cell. Melanoma Res. 24: 462–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T., Takeuchi S., Hotta E., 2004. The melanocortin receptor-1 gene but not the proopiomelanocortin gene is expressed in melanoblasts and contributes their differentiation in the mouse skin. Pigment Cell Res. 17: 627–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft K. A., Bocan T. M., Krause B. R., 1991. Rapid on-line determination of cholesterol distribution among plasma lipoproteins after high-performance gel filtration chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 32: 859–866 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krude H., Biebermann H., Luck W., Horn R., Brabant G., et al. , 1998. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat. Genet. 19: 155–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S., Edelmann K. H., de la Torre J. C., Gorney R., Oldstone M. B., 2003. Mechanisms for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein cleavage, transport, and incorporation into virions. Virology 314: 168–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz O., ter Meulen J., Klenk H. D., Seidah N. G., Garten W., 2001. The lassa virus glycoprotein precursor GP-C is proteolytically processed by subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 12701–12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. B., 1986. Vitiligo (vit). Mouse News Lett 74: 125 [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Ito M., Zhou F., Youngson N., Zuo X., et al. , 2008. A maternal-zygotic effect gene, Zfp57, maintains both maternal and paternal imprints. Dev. Cell 15: 547–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K. A., Kunte A. S., Tambe-Ebot E., Rawson R. B., 2009. Alternative processing of sterol regulatory element binding protein during larval development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 181: 119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K. J., Pinson K. I., Kelly O. G., Brennan J., Zupicich J., et al. , 2001. Functional analysis of secreted and transmembrane proteins critical to mouse development. Nat. Genet. 28: 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoliu L., Oetting W. S., Bennett D. C., 2011. Color Genes. European Society for Pigment Cell Research. Available at: http://www.espcr.org/micemut

- Murakami T., Kondo S., Ogata M., Kanemoto S., Saito A., et al. , 2006. Cleavage of the membrane-bound transcription factor OASIS in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Neurochem. 96: 1090–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra D., Xing X., Davies S., Bryan J., Franz C., et al. , 2007. Site-1 protease is essential for endochondral bone formation in mice. J. Cell Biol. 179: 687–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears J. S., Jung R. T., Bartlett W., Browning M. C., Kenicer K., et al. , 1992. A case of skin hyperpigmentation due to alpha-MSH hypersecretion. Br. J. Dermatol. 126: 286–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin D. L., Teijaro J. R., Sullivan B. M., Urata S., Rutschmann S., et al. , 2011. Hypomorphic mutation in the site-1 protease Mbtps1 endows resistance to persistent viral infection in a cell-specific manner. Cell Host Microbe 9: 212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenneville S., Verde G., Corsinotti A., Kapopoulou A., Jakobsson J., et al. , 2011. In embryonic stem cells, ZFP57/KAP1 recognize a methylated hexanucleotide to affect chromatin and DNA methylation of imprinting control regions. Mol. Cell 44: 361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggo C., Rapin N., Stirling J., Gobeil P., Smith-Windsor E., et al. , 2002. Luman, the cellular counterpart of herpes simplex virus VP16, is processed by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 5639–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau K., Kauser S., Pritchard L. E., Warhurst A., Oliver R. L., et al. , 2007. Proopiomelanocortin (POMC), the ACTH/melanocortin precursor, is secreted by human epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes and stimulates melanogenesis. FASEB J. 21: 1844–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai J., Rawson R. B., Espenshade P. J., Cheng D., Seegmiller A. C., et al. , 1998. Molecular identification of the sterol-regulated luminal protease that cleaves SREBPs and controls lipid composition of animal cells. Mol. Cell 2: 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A., Tobin D. J., Shibahara S., Wortsman J., 2004. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol. Rev. 84: 1155–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling J., O’hare P., 2006. CREB4, a transmembrane bZip transcription factor and potential new substrate for regulation and cleavage by S1P. Mol. Biol. Cell 17: 413–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent M. J., Sanchez A. J., Erickson B. R., Basak A., Chretien M., et al. , 2003. Crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever virus glycoprotein proteolytic processing by subtilase SKI-1. J. Virol. 77: 8640–8649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu K., Graham A., Cook D., Thody A. J., 1997. Characterisation of ACTH peptides in human skin and their activation of the melanocortin-1 receptor. Pigment Cell Res. 10: 288–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Goldstein J. L., Hammer R. E., Moon Y. A., Brown M. S., et al. , 2001. Decreased lipid synthesis in livers of mice with disrupted site-1 protease gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 13607–13612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Rawson R. B., Komuro R., Chen X., Dave U. P., et al. , 2000. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol. Cell 6: 1355–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Shen X., Wu J., Sakaki K., Saunders T., et al. , 2006. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates cleavage of CREBH to induce a systemic inflammatory response. Cell 124: 587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X., Sheng J., Lau H. T., McDonald C. M., Andrade M., et al. , 2012. Zinc finger protein ZFP57 requires its co-factor to recruit DNA methyltransferases and maintains DNA methylation imprint in embryonic stem cells via its transcriptional repression domain. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 2107–2118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]