Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) compared with open distal pancreatectomy (ODP).

METHODS: Meta-analysis was performed using the databases, including PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews. Articles should contain quantitative data of the comparison of LDP and ODP. Each article was reviewed by two authors. Indices of operative time, spleen-preserving rate, time to fluid intake, ratio of malignant tumors, postoperative hospital stay, incidence rate of pancreatic fistula and overall morbidity rate were analyzed.

RESULTS: Nine articles with 1341 patients who underwent pancreatectomy met the inclusion criteria. LDP was performed in 501 (37.4%) patients, while ODP was performed in 840 (62.6%) patients. There were significant differences in the operative time, time to fluid intake, postoperative hospital stay and spleen-preserving rate between LDP and ODP. There was no difference between the two groups in pancreatic fistula rate [random effects model, risk ratio (RR) 0.996 (0.663, 1.494), P = 0.983, I2 = 28.4%] and overall morbidity rate [random effects model, RR 0.81 (0.596, 1.101), P = 0.178, I2 = 55.6%].

CONCLUSION: LDP has the advantages of shorter hospital stay and operative time, more rapid recovery and higher spleen-preserving rate as compared with ODP.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Distal pancreatectomy, Pancreatic fistula, Spleen-preserving, Morbidity

INTRODUCTION

With improvement of advanced surgical techniques and endoscopic instrument, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) is becoming a primary modality for the treatment of benign or borderline tumors of distal pancreas[1-3].

Recently, several researches have shown the advantages of LDP of shorter hospital stay and operative time and less intraoperative blood loss[4-5]. But the efficacy of LDP compared with open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) required further assessment, especially the incidence of pancreatic fistula (PF) which may lead to further complications such as an intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis or lethal bleeding[6]. With a better understanding of the anatomy and immune function of spleen, especially the increased risks of overwhelming post splenectomy infection (OPSI) and long-term lung thrombosis[7], laparoscopic spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy (LSPDP) was performed first by Kimura et al[8] and Warshaw[9]. However, the role of “laparoscopy” in the spleen preservation is still unclear.

All the published studies we retrieved were based on a small number of patients and no randomized trials were available. Therefore, we strictly established the inclusion criteria and conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to evaluate more systematically the feasibility and safety of LDP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

We searched databases of PubMed, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews for the literatures comparing LDP and ODP published between January 1995 and June 2011. The language of the publications was confined to English. Two investigators reviewed the titles and abstracts, and assessed the full text to establish the eligibility. The search strategies were as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

Database and search strategy

| Database | Search strategy |

| PubMed | "laparoscopy" (MeSH terms) or "laparoscopy" (all fields) or "laparoscopic" (all fields) or (minimally (all fields) and invasive (all fields) and ("pancreas" (MeSH terms) or "pancreas" (all fields) or "pancreatic" (all fields) and "humans" (MeSH terms) and English (lang) and "1995/1/1" (PDAT): "2011/06/30" (PDAT) |

| Web of Science | "pancreas" or "pancreatic" or "pancreatectomy" and "laparoscopy" or "laparoscopic" (limited year: 1995-2011) |

| Cochrane Library | "pancreas" or "pancreatic" or "pancreatectomy" and "laparoscopy" or "laparoscopic" (limited year: 1995-2011) |

| BIOSIS Previews | "pancreas" or "pancreatic" or "pancreatectomy" and "laparoscopy" or "laparoscopic" (limited year: 1995-2011) (related term and limited English and human and year: 1995-2011) |

PDAT: Pulication date; MeSH: Medical subject headings.

Inclusion criteria

All clinical studies should meet the following criteria for the meta-analysis: (1) published in English with data comparing ODP and LDP; (2) with clear case selection criteria, containing at least the following information: the number of cases, surgical methods and perioperative data; (3) continuous variables (e.g., operative time and hospital stay) expressed in mean ± SD. Dichotomous variables (e.g., incidence of PF and number of death) such as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI); and (4) if there was overlap between authors, centers, or patient cohorts, the higher quality or recent literatures were selected.

Exclusion criteria

The papers containing any of the followings were excluded: (1) intra-operative conversion of LDP to an open laparotomy, which was classified into the laparoscopic group; (2) single surgical procedure; and (3) laparoscopy-assisted DP or hand-assisted LDP.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently extracted the data using a unified datasheet, and decided the controversial issues through discussion. Extracted data included: first author, study period, the number of cases, operative time, spleen preservation, hospital stay, cases of malignant tumors, incidence of post-operative complications, and PF. Selected documents were rated according to the Grading of the Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine (Oxford, United Kingdom; www.cebm.net).

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) and the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUORUM) as a guideline[10,11]. Weighted mean differences (WMD) were used for continuous variables, and relative risk for dichotomous variables. P values < 0.05 indicated statistically significant difference between the two groups. When heterogeneity test showed no significant differences (P > 0.05), we used fixed effects model to calculate the summary statistics. When the heterogeneity test showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), we used random effects model based on DerSimonian and Laird method. If the heterogeneity was high or extracted data were less than three sets, we performed descriptive analysis. The potential publication bias was determined by the Begg’s test and funnel plots based on the dichotomous variables. All data were analyzed using Stata SE11.0 software.

RESULTS

We retrieved 1663 papers in English. After the titles and abstracts were reviewed, papers without comparison of LDP and ODP were excluded. As a result, a total of 20 studies[12-31] were collected, of which 11 studies were excluded because of intraoperative conversion and using “assisted” approach. However, we preserved them for the analysis as “conversion to open”. Finally, 9 studies[23-31] were included and extracted for detailed data. A flow chart of search strategies is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of search strategies. The initial search strategy retrieved 1663 papers in English. Finally 9 studies were included and extracted for detailed data. LDP: Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy; ODP: Open distal pancreatectomy.

Totally, 1341 patients (sample sizes ranging from 44 to 310) entered into this meta-analysis, including 501 (37.4%) cases of LDP and 840 (62.6%) cases of ODP. The detailed study design and surgical techniques in 10 trials are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the literatures

| Ref. | Study year | Nation |

Case number |

Study type |

Pancreatictransection |

Spleen persevation |

Totalmorbidity |

PF |

Mortality % |

Level of evidence | ||||||

| LDP | ODP | LDP | ODP | LDP | ODP | LDP | ODP | LDP | ODP | LDP | ODP | |||||

| Aly et al[23] | 1998-2009 | Japan | 40 | 35 | Retro | Stapler | Stapler/scalpel + suture | 13 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Baker et al[24] | 2003-2008 | USA | 27 | 85 | Pros | Stapler/ scalpel + micro sealer device | Scalpel + suture | NA | 10 | 30 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2b | |

| Butturini et al[25] | 1999-2006 | Italy | 43 | 73 | Retro | Stapler | Scalpel + suture | 19 | 8 | 21 | 33 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2b |

| Casadei et al[26] | 2000-2010 | Italy | 22 | 22 | Case control | Stapler | Stapler | NA | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2b | |

| DiNorcia et al[27] | 1991-2009 | USA | 71 | 192 | Retro | Stapler | Stapler/ Scalpel + suture | 11 | 30 | 20 | 84 | 8 | 27 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Eom et al[28] | 1995-2006 | Korea | 31 | 62 | Retro | Stapler | Scalpel + suture | 13 | NA | 11 | 15 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Jayaraman et al[29] | 2003-2009 | USA | 74 | 236 | Retro | Stapler/ scalpel + suture | Stapler/ scalpel + suture | 14 | 33 | 11 | 94 | 6 | 31 | NA | 4 | |

| Kim et al[30] | NA | Korea | 93 | 35 | Retro | Stapler | Stapler/ Scalpel + suture | 38 | 2 | 23 | 11 | 8 | 5 | NA | 4 | |

| Vijan et al[31] | 2004-2009 | USA | 100 | 100 | Retro | Stapler | NA | 25 | NA | 34 | 29 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

Retro: Retrospective observational study; Pros: Prospective observational study; LDP: Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy; ODP: Open distal pancreatectomy; PF: Pancreatic fistula; NA: Not available.

Intraoperative effects

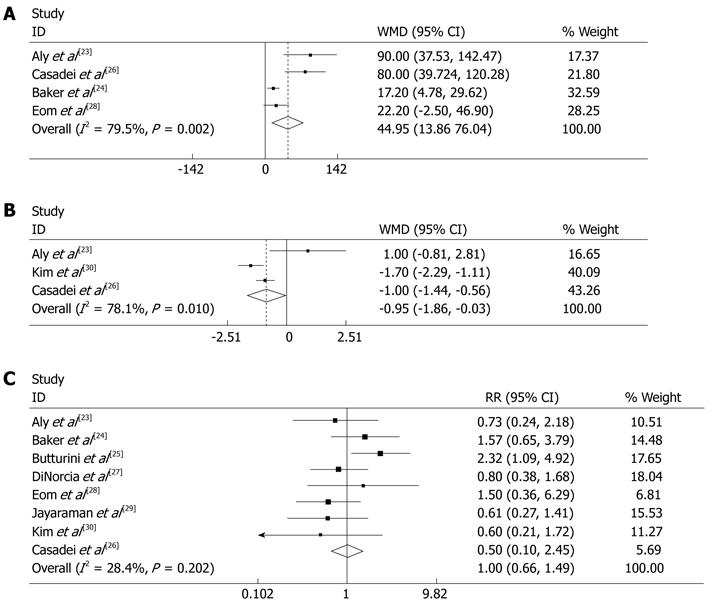

The operative time was reported in four articles[23,24,26,28]. Meta-analysis of the pooled data showed that the operative time of ODP was significantly shorter than LDP [random effects model, WMD 44.947 (13.857, 76.037), P = 0.005] (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the pooled data. A: operative time was significant ly shorter in open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) than in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) [random effects model, WMD 44.947 (13.857, 76.037), P = 0.005]; B: Time for fluid intake was shorter in LDP than in ODP [random effects model, WMD -0.948 (-1.863, 0.032), P = 0.042]; C: Pancreatic fistula occurrence has no significant difference between LDP and ODP [random effects model, RR 0.996 (0.663, 1.494), P = 0.983, I2 = 28.4%]. Weights are from random effects analysis. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; WMD: Weighted mean differences.

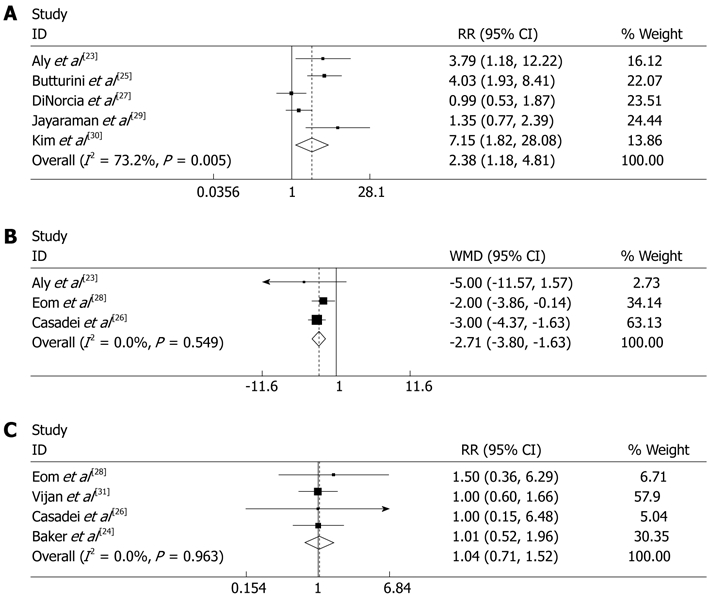

In the included articles, five studies[23,25,27,29,30] covered the spleen-preserving DP, 95 cases (29.6%) of LSPDP were conducted among 321 cases of LDP as compared with 76 cases (13.3%) of SPDP among 571 cases of ODP. The pooled data showed that the spleen-preserving rate in LDP was significantly higher than in ODP [random effects model, RR 2.380 (1.177, 4.812), P = 0.016, I2 = 73.2%], (Figure 3A). Although there was moderate heterogeneity, spleen-preservation occurred more often in LDP. Most authors tended to use the “Kimura method”, and “Warshaw method” was used in a few LDPs and in cases with severe adhesion or vessels involved in tumors. Technical details of spleen-preservation are listed in Table 3.

Figure 3.

The pooled data. A: The spleen-preserving rate of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) was significantly higher than open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) [random effects model, RR 2.380 (1.177, 4.812), P = 0.016, I2 = 73.2%]; B: Postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in LDP than in ODP [random effects model, WMD -2.713 (-3.799, 1.628), P = 0.00]; C: The proportion of malignant tumors showed no significant difference between LDP and ODP [fixed effects model, RR 1.036 (0.708, 1.516), P = 0.000, I2 = 0%]. Weights are from random effects analysis. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; WMD: Weighted mean differences.

Table 3.

Technical details of spleen-preservation

| Ref. |

Spleen preserving % |

Technical details | |

| LDP | ODP | ||

| Aly et al[23] | 32.5 | 8.6 | Both procedures, spleen vessel ligation were performed, leaving the short gastric vessels to supply the spleen (Warshaw) |

| Baker et al[24] | NA | In ODP, the benign and premalignant pathology, the spleen was routinely saved by means of the splenic vein and artery preserved | |

| In LDP, splenic salvage by means of Warshaw: ligating the splenic artery and vein but preserve the short gastric vessel | |||

| Butturini et al[25] | 44.2 | 11.0 | Both procedures, exposing the splenic vein up to the splenic hilum; the distal pancreas was detached from the splenic artery in the opposite direction by tractioning the parenchyma |

| Casadei et al[26] | NA | Mobilization of the distal pancreas from retroperitoneum and splenic vessels | |

| DiNorcia et al[27] | 15.5 | 15.6 | For spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy, an attempt to spare the splenic artery and vein was made in all patients |

| Eom et al[28] | 41.9 | NA | For spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy, both the splenic artery and vein were preserved |

| Jayaraman et al[29] | 18.9 | 14.0 | When splenic preservation was performed, the splenic vein and artery were isolated |

| Kim et al[30] | 40.9 | 5.70 | In spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy, both the splenic artery and vein were preserved. In one case, the splenic artery was ligated with preservation of splenic vein. In the other case, both the splenic artery and vein were ligated, with preservation of short gastric vessels (Warshaw) |

| Vijan et al[31] | 25 | NA | If splenic preservation is indicated, the pancreas is dissected off the splenic vessels |

LDP: Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy; ODP: Open distal pancreatectomy; NA: Not available.

Among 714 cases of LDP, 100 cases (14.0%) converted to open surgery and 6 cases converted to the hand-assisted approach as shown in 20 articles[12-31] because of severe bleeding, abdominal adhesions, large tumor, organ injury, and difficult anatomy.

The techniques of pancreatic stump closure in the included studies are summarized in Table 4. Because the pooled data was derived from 9 institutions, no single technique was used for both procedures, but similar principles were applied. In LDP, the gland was divided by staplers and in ODP, stapler or scalpel + suture was used. In some cases, bio-sealant was attached to the stump reported by Baker, DiNorcia, Kim and Aly[23,24,27,30].

Table 4.

Technique of pancreatic stump closure

| Ref. | Technique description | |

| Aly et al[23] | LDP | The pancreatic parenchyma was transected using a laparoscopic linear stapler |

| ODP | The pancreatic parenchyma was transected using a scalpel, and the main pancreatic duct was ligated using nonabsorbable sutures. The pancreatic stump was closed with fish-mouth sutures. A linear stapler was used to transect the pancreatic parenchyma | |

| Baker et al[24] | LDP | The gland was divided by one of 3 mechanisms: vascular stapler, harmonic scalpel, or harmonic scalpel following ablation at the pancreatic resection margin with the Habib 4*3 microsealer device |

| ODP | Directly ligate the pancreatic duct when visible with a monofilament absorbable suture. The neck of the gland was oversewn with nonabsorbable monofilament suture | |

| Butturini et al[25] | LDP | The pancreatic body was transected by a linear endostapler |

| ODP | Pancreatic parenchyma was sharply transected. The main pancreatic duct was closed with nonabsorbable sutures (polypropylene 4/0). Subsequently the pancreatic stump was oversewn with interrupted mattress nonabsorbable sutures or closed using a linear stapler | |

| Casadei et al[26] | LDP | The pancreas was divided at the neck using an endo-GIA instrument |

| ODP | The pancreas was divided using GIA 55 | |

| DiNorcia et al[27] | LDP | Sutures, staples, sutures and staples combined, or staples with bioabsorbable staple-line reinforcement |

| ODP | ||

| Eom et al[28] | LDP | The pancreas was transected using the 48- or 35-mm vascular endoscopic linear stapler |

| ODP | The pancreatic parenchyma was divided using a blade and electrocautery. The main pancreatic duct was ligated with nonabsorbable sutures, and the transected pancreas was occluded with interlocking interrupted mattress sutures of 4-0 black silk and reinforced with 4-0 polypropylene | |

| Jayaraman et al[29] | LDP | The pancreas was stapled using a vascular stapler with or without a Seamguard attachment |

| ODP | Ligate pancreas with staples, or via suture ligation, or a combination of techniques | |

| Kim et al[30] | LDP | For pancreatic transaction, straight endoscopic linear staplers of various sizes (staple height, 3.5-4.2 mm) were used according to the thickness or hardness of the pancreas. Four or five small titanium clips were applied along the stapling line |

| ODP | The pancreatic stump underwent main duct ligation, multiple suture ligation of the branch duct exposed at the resection margin, and reinforcement of the mattress suture to the pancreas stump | |

| Vijan et al[31] | LDP | The pancreatic parenchyma is divided with the harmonic scalpel (preferred) or with an Endo GIA stapler |

| ODP | NA |

LDP: Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy; ODP: Open distal pancreatectomy; NA: Not available; GIA: Gastrointestinal incision anastomose.

Postoperative outcome

Three studies[23,26,30] contained information about time to post-operative fluid intake. Meta-analysis of the pooled data showed that time to fluid intake was shorter in LDP than in ODP [random effects model, WMD -0.948 (-1.863, 0.032), P = 0.042] (Figure 2B). Another three studies[23,26,28] reported the postoperative hospital stay. The pooled data showed that postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in LDP than in ODP [random effects model, WMD -2.713 (-3.799, 1.628), P = 0.00] (Figure 3B).

The proportion of malignant tumors reported by four articles[24,26,28,31] was 20% (36/180) in LDP and 20.1% (54/269) in ODP, and most of them were adenocarcinomas. The proportion of malignant tumors in LDP was not significantly different as compared with ODP [fixed effects model, RR 1.036 (0.708, 1.516), P = 0.000, I2 = 0%] (Figure 3C). There was no difference in patient selection between the two groups.

All studies illustrated the criteria for PF. Seven articles followed the criteria by International Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF): any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase level > 3 times that of normal serum amylase level. Eom et al[28] used the following PF criteria: drainage exceeding 30 mL with an amylase level > 600 U/dL on or after postoperative week 1. Kim et al[30] chose the PF criteria: a level of drain amylase five times greater than the serum level and drainage of more than 30 mL 5 d or longer after the operation.

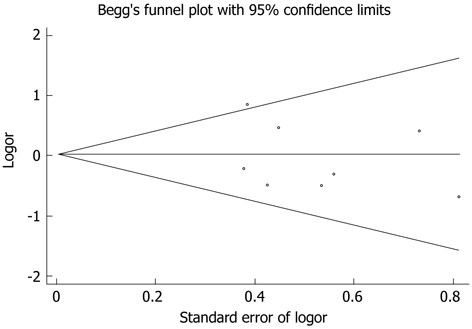

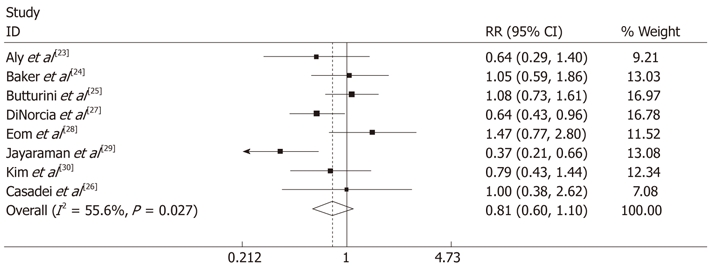

One study was excluded[31] due to no available data, 8 studies reported 50 (12.5%) PF cases in 401 LDP (12.5%) and 99 (13.4%) PF cases in ODP. The pooled data showed no significant difference between the two groups [random effects model, RR 0.996 (0.663, 1.494), P = 0.983, I2 = 28.4%] (Figure 2C) and no publication bias was found by Begg’s test (Figure 4). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the overall morbidity between LDP and ODP [random effects model, RR 0.81 (0.596, 1.101), P = 0.178, I2 = 55.6%] (Figure 5), although there was moderate heterogeneity.

Figure 4.

Begg’s test showing no publication bias of pancreatic fistula occurrence.

Figure 5.

There was no significant difference in overall morbidity between laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and open distal pancreatectomy [random effects model, risk ratio 0.81 (0.596, 1.101), P = 0.178, I2 = 55.6%] and there was moderate heterogeneity. Weights are from random effects analysis. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio.

DISCUSSION

Since Cuschieri and Gagner[32,33] documented the earliest attempts at LDP in humans, there have been an increasing number of reports indicating the advantages of LDP of minimal trauma, rapid recovery, and shorter hospital stay. But due to the high postoperative morbidity and a high level of laparoscopic technical requirements and extensive experiences in open pancreatic surgery, the progression of LDP was considerably restricted. In particular, the randomized clinical trials (RCT), which are the ideal objects of meta-analysis, have been extremely difficult to achieve. The published articles comparing LDP and ODP were all retrospective studies with common defects such as long-term research, small number of cases and incomplete data. With the development of surgical technology, potential bias and inappropriate results could be produced from the recent literature analyzed with the earlier clinical data. Furthermore, due to a relatively low incidence of left pancreas diseases, there are few LDP studies with large sample sizes. Therefore, with strictly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, we performed a comprehensive analysis to assess the current status of LDP vs ODP.

The proportions of malignant tumors were 20% in both LDP and ODP, which showed no difference in the patient selection between the two groups. DP was most frequently used in the treatment of benign or borderline tumors, which was in agreement with previous studies[34,35] using either “laparoscopy” or “open”.

The most important indicators to represent the operative effect were shorter operative time, time to fluid intake and hospital stay, and less blood loss, low conversion rate and high spleen-preservating rate. These indicators have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of the laparoscopic procedures. In this meta-analysis, the operative time of LDP was longer than ODP (WMD 44.947, P = 0.005), but a recent research showed that operative time is becoming shorter with the improved expertise of surgeons[17]. And the time to fluid intake and post-operative hospital stay were also shorter in LDP than in ODP (WMD -0.948, P = 0.042) and (WMD -2.713, P = 0.00). Blood loss estimate was not conducted in this study because of different numeric types. The results of the included articles showed that blood loss was less in LDP than in ODP, which were similar with other literatures[18,19]. In addition, conversion rate of LDP from the pooled data showed a low level of 14% in 714 LDPs because of severe bleeding and abdominal adhesion[14].

The rate of spleen-preservation ranged from 15.5% to 44.2% in LDP and from 5.7% to 15.6% in ODP as shown in Table 3. Kimura method was more frequently used as compared with Warshaw method used when intraoperative bleeding, adhesion, and blood vessels embedded by the tumors occurred. Effects of the two surgical methods have long been a concern. Rodriguez et al[36] retrospectively reported Kimura method used in 185 cases compared with Warshaw method in 74 cases of LDP from 1994 to 2004; the two groups had no statistically significant difference in occurrence of ascites (9% vs 8%), intra-abdominal abscess (14% vs 8%), pancreatic leakage (33% vs 36%) and incision complications (10% vs 8%). Although Warshaw method was proved to be sufficiently safe[37,38], due to individual differences of the short gastric vessels, spleen relied entirely on the short gastric blood vessels which inevitably brought some uncertainties. In the event of severe splenic infarction, reoperation was often required. So spleen-preservation by Kimura method was widely accepted in LDP, but under some special conditions, such as bleeding, adherent tumor and difficult anatomy, Warshaw method could elevate the spleen-preserving rate. In this meta-analysis, five articles described the spleen-preserving DP, the pooled data showed that the spleen-preserving rate of LDP was significantly higher than that of ODP (RR 2.380, P = 0.016, I2 = 73.2%). Although there was moderate heterogeneity, spleen-preservation occurred more often in LDP. The reasons for the high spleen-preserving rate in LDP may be as follows: (1) surgeons in different stages of learning curve may achieve different clinical outcomes. In the early period, because of the immature LDP technique, especially laparoscopic vascular treatment, fewer cases of LSPVP were performed; and (2) many cases of ODP without spleen-preservation were included in each study, leading to a low spleen-preservation rate of ODP.

PF was the most important complications after DP which resulted in serious consequences such as extended hospital stay, poor quality of life, even intra-abdominal bleeding, and infection. Although at some high-volume centers, PF after DP has declined over the past decade, the incidence of PF still kept from 5% to 30%[39-41]. In this study, a large variation in the PF rate was recorded, ranging from 8.1% to 27.9% in LDP and 6.5% to 18.2% in ODP. The major reason for the variability may be lacking uniform criteria for PF. The diagnostic criteria of PF were generally based on clinical signs and laboratory indicators, including the occurrence time, the daily amount of leakage, leakage amylase, the duration, etc. The ISGPF criterion[42] was most frequently used, but it failed to explain whether the drainage amount was related to the diagnosis of PF. Because of the lack of different quantitative indicators, other criteria were also questioned[43,44].

The original disease, pancreatic transection, pancreas texture, blood supply, and stump closure are factors affecting the incidence of PF. Recently, body mass index > 25 kg/m2 was also reported contributing to the increased incidence of PF after DP[45]. However, the treatment of pancreatic stump is a unique controllable factor for preventing PF. In order to reduce the incidence of PF, a variety of stump closure techniques were applied or used in combination, but the coexistence of methods may reflect the lacking of a widely accepted and effective method. In this study, stapler was used in LDP while both stapler/scalpel + suture were used in ODP. The surgeons could choose different staplers according to the pancreatic texture and size in LDP. And in some groups, small titanium clips were applied along the stapling line[30] and fibrin glue was splashed over the pancreatic stump in an attempt to prevent PF and postoperative bleeding[23,24,27,30]. Subset analysis could not be accomplished as no detailed data was available. A published meta-review analyzed 16 articles with 2286 patients who underwent DP and compared the preventive effect for PF between 671 cases with stapler closure and 1615 cases with suture closure. The results showed no significant differences between suture and stapler closure of the pancreatic remnant with respect to the PF or intra-abdominal abscess[46]. Likewise, the pooled data of this study showed no significant difference both in the incidence of PF (RR 0.996, P = 0.983) and overall morbidity between LDP and ODP (RR 0.81, P = 0.178).

The authentication strength of this study may be affected by the following factors: (1) publication bias: some gray literatures which contained negative results were difficult to obtain because most authors tended to show positive results; (2) grouping bias: notwithstanding the literatures dealing with significantly different diseases and surgical methods have been excluded in this study, in practice, patients should be grouped inevitably according to the disease condition and surgeons’ choices; and (3) observation bias: due to the varied measurement methods used by different authors, significantly different results were almost inevitable in the non-RCT or non-blind RCT studies.

In summary, LDP has shown the advantages of intraoperative effects, rapid recovery and spleen-preservation for benign and borderline tumors. But the superiority has not been displayed in preventing the overall morbidity and occurrence of PF. Thus, the RCT studies with a large sample size should be conducted and new surgical techniques should be introduced in future studies.

COMMENTS

Background

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) is becoming a primary treatment modality for benign or borderline tumors of distal pancreas. But due to the high postoperative morbidity and a high level of laparoscopic technical requirements and extensive experiences in open pancreatic surgery, the progression of LDP was considerably restricted.

Research frontiers

Recently, several studies have shown shorter hospital stay and operative time and less intraoperative blood loss in LDP. But the efficacy of LDP compared with open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) required further assessment.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Pancreatic fistula (PF) and spleen-preservation in LDP have been the major concern after the surgery. What the role of “laparoscopy” in the spleen preservation and PF prevention is unclear. In this meta-analysis, the authors pointed out that LDP has the advantages of shorter hospital stay and operative time, more rapid recovery and higher spleen-preserving rate compared with ODP.

Applications

Due to a relatively low incidence of left pancreas diseases, fewer LDP studies with a large sample size have been published. Especially the RCT clinical study, which is the ideal object of meta-analysis, is extremely difficult to accomplish. This meta-analysis assessed the safety and feasibility of LDP compared with ODP based on the review of the literature published over the past 15 years.

Peer review

This paper is a systematic review of the laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. The summary of LDP experiences and results is interesting.

Footnotes

Supported by The key project grant from the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province, No. 2011C13036-2

Peer reviewer: Yasuhiro Fujino, MD, PhD, Director, Department of Surgery, Hyogo Cancer Center, 13-70 Kitaoji-cho, Akashi 673-8558, Japan

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Nakamura M, Ueda J, Kohno H, Aly MY, Takahata S, Shimizu S, Tanaka M. Prolonged peri-firing compression with a linear stapler prevents pancreatic fistula in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:867–871. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giger U, Michel JM, Wiesli P, Schmid C, Krähenbühl L. Laparoscopic surgery for benign lesions of the pancreas. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:452–457. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler KM, Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Schmidt CM, Bishop SN, Moreno J, Matos JM, Zyromski NJ, House MG, Madura JA, et al. Pancreatic surgery: evolution at a high-volume center. Surgery. 2010;148:702–709; discussion 702-709. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwin B, Mala T, Mathisen Ø, Gladhaug I, Buanes T, Lunde OC, Søreide O, Bergan A, Fosse E. Laparoscopic resection of the pancreas: a feasibility study of the short-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:407–411. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nau P, Melvin WS, Narula VK, Bloomston PM, Ellison EC, Muscarella P. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with splenic conservation: an operation without increased morbidity. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:846340. doi: 10.1155/2009/846340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez JR, Germes SS, Pandharipande PV, Gazelle GS, Thayer SP, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Implications and cost of pancreatic leak following distal pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2006;141:361–365; discussion 366. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeper MM, Niedermeyer J, Hoffmeyer F, Flemming P, Fabel H. Pulmonary hypertension after splenectomy? Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:506–509. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura W, Inoue T, Futakawa N, Shinkai H, Han I, Muto T. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein. Surgery. 1996;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1988;123:550–553. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290032004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke M, Horton R. Bringing it all together: Lancet-Cochrane collaborate on systematic reviews. Lancet. 2001;357:1728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genth E. [Patient education in rheumatologic care--a review] Z Rheumatol. 2008;67:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00393-008-0279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker MS, Bentrem DJ, Ujiki MB, Stocker S, Talamonti MS. Adding days spent in readmission to the initial postoperative length of stay limits the perceived benefit of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy when compared with open distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2011;201:295–299; discussion 295-299. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho CS, Kooby DA, Schmidt CM, Nakeeb A, Bentrem DJ, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ahmad SA, et al. Laparoscopic versus open left pancreatectomy: can preoperative factors indicate the safer technique? Ann Surg. 2011;253:975–980. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finan KR, Cannon EE, Kim EJ, Wesley MM, Arnoletti PJ, Heslin MJ, Christein JD. Laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy: a comparison of outcomes. Am Surg. 2009;75:671–679; discussion 671-679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S, et al. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438–446. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooby DA, Hawkins WG, Schmidt CM, Weber SM, Bentrem DJ, Gillespie TW, Sellers JB, Merchant NB, Scoggins CR, Martin RC, et al. A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:779–785, 786-787. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto T, Shibata K, Ohta M, Iwaki K, Uchida H, Yada K, Mori M, Kitano S. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and open distal pancreatectomy: a nonrandomized comparative study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:340–343. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181705d23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura Y, Uchida E, Aimoto T, Matsumoto S, Yoshida H, Tajiri T. Clinical outcome of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang CN, Tsui KK, Ha JP, Wong DC, Li MK. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: a comparative study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teh SH, Tseng D, Sheppard BC. Laparoscopic and open distal pancreatic resection for benign pancreatic disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1120–1125. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0222-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velanovich V. Case-control comparison of laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aly MY, Tsutsumi K, Nakamura M, Sato N, Takahata S, Ueda J, Shimizu S, Redwan AA, Tanaka M. Comparative study of laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:435–440. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker MS, Bentrem DJ, Ujiki MB, Stocker S, Talamonti MS. A prospective single institution comparison of peri-operative outcomes for laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:635–643; discussion 643-645. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butturini G, Partelli S, Crippa S, Malleo G, Rossini R, Casetti L, Melotti GL, Piccoli M, Pederzoli P, Bassi C. Perioperative and long-term results after left pancreatectomy: a single-institution, non-randomized, comparative study between open and laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2871–2878. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casadei R, Ricci C, D’Ambra M, Marrano N, Alagna V, Rega D, Monari F, Minni F. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy in pancreatic tumours: a case-control study. Updates Surg. 2010;62:171–174. doi: 10.1007/s13304-010-0027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiNorcia J, Schrope BA, Lee MK, Reavey PL, Rosen SJ, Lee JA, Chabot JA, Allendorf JD. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy offers shorter hospital stays with fewer complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1804–1812. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1264-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eom BW, Jang JY, Lee SE, Han HS, Yoon YS, Kim SW. Clinical outcomes compared between laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1334–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jayaraman S, Gonen M, Brennan MF, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Allen PJ. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: evolution of a technique at a single institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SC, Park KT, Hwang JW, Shin HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Han DJ. Comparative analysis of clinical outcomes for laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection and open distal pancreatic resection at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2261–2268. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9973-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijan SS, Ahmed KA, Harmsen WS, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Kendrick ML. Laparoscopic vs open distal pancreatectomy: a single-institution comparative study. Arch Surg. 2010;145:616–621. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00642443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palanivelu C, Shetty R, Jani K, Sendhilkumar K, Rajan PS, Maheshkumar GS. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: results of a prospective non-randomized study from a tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:373–377. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor C, O’Rourke N, Nathanson L, Martin I, Hopkins G, Layani L, Ghusn M, Fielding G. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: the Brisbane experience of forty-six cases. HPB ( Oxford) 2008;10:38–42. doi: 10.1080/13651820701802312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez JR, Madanat MG, Healy BC, Thayer SP, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Distal pancreatectomy with splenic preservation revisited. Surgery. 2007;141:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shoup M, Brennan MF, McWhite K, Leung DH, Klimstra D, Conlon KC. The value of splenic preservation with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:164–168. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrère N, Abid S, Julio CH, Bloom E, Pradère B. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with excision of splenic artery and vein: a case-matched comparison with conventional distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. World J Surg. 2007;31:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, Fabre JM, Boulez J, Baulieux J, Peix JL, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebedyev A, Zmora O, Kuriansky J, Rosin D, Khaikin M, Shabtai M, Ayalon A. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1427–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8221-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corcione F, Marzano E, Cuccurullo D, Caracino V, Pirozzi F, Settembre A. Distal pancreas surgery: outcome for 19 cases managed with a laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1729–1732. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bassi C, Butturini G, Molinari E, Mascetta G, Salvia R, Falconi M, Gumbs A, Pederzoli P. Pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatic resection. The importance of definitions. Dig Surg. 2004;21:54–59. doi: 10.1159/000075943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Büchler MW, Friess H, Wagner M, Kulli C, Wagener V, Z’Graggen K. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg. 2000;87:883–889. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seeliger H, Christians S, Angele MK, Kleespies A, Eichhorn ME, Ischenko I, Boeck S, Heinemann V, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Risk factors for surgical complications in distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;200:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou W, Lv R, Wang X, Mou Y, Cai X, Herr I. Stapler vs suture closure of pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2010;200:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]