Abstract

We report on small but reproducible human cerebral evoked potentials after bilateral nonperceptible laser needle (658 nm, 40 mW, 500 μm, 1 Hz) irradiation of the Neiguan acupoint (PC6). The results which are unique in scientific literature were obtained in a 26-year-old female healthy volunteer within a joint study between the Medical University of Graz, the Karl-Franzens University of Graz, and the Graz University of Technology. The findings of the 32-channel evoked potential analysis indicate that exposure to laser needle stimulation with a frequency of 1 Hz can modulate the ascending reticular activating system. Further studies are absolutely necessary to confirm or refute the preliminary findings.

1. Introduction

The irradiation of the skin overlying the median nerve of the wrist in humans using a helium-neon laser stimulation with a wavelength of 632.5 nm, an output power of 1 mW, and a frequency of 3.1 Hz, can produce a somatosensory evoked potential obtained at the Erb's point on the shoulder. This evidence of photosensitivity in peripheral nerves was found by Walker and Akhanjee already in 1984 [1].

The laser needle technology was invented at the University of Paderborn and first investigated scientifically at the Medical University of Graz [2]. The method does not puncture the skin; the needles are only applied at the surface of the skin.

The aim of this preliminary paper was to investigate if there are any measurable evoked potentials in the brain after “laser needle” stimulation at the Neiguan acupoint (PC6), which is also located at the wrist, near the median nerve.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject

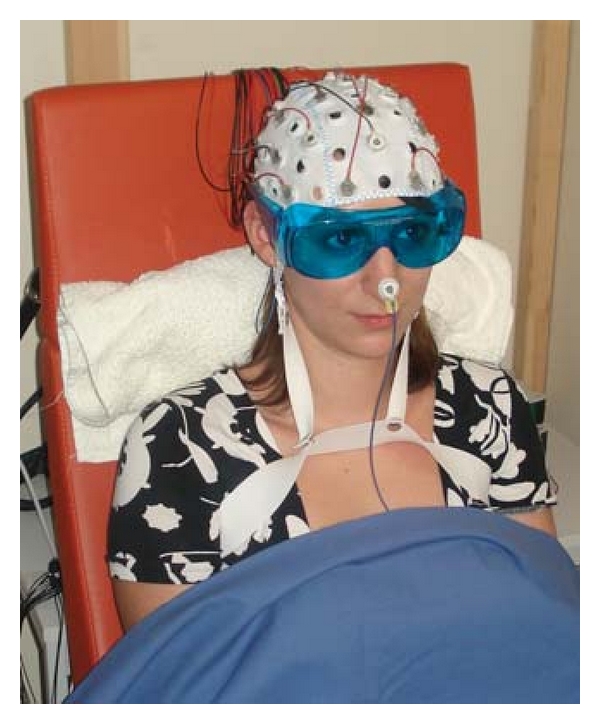

The subject for our investigations was a 26-year-old female who was sitting in a special sound booth. The box is located at the Department of Psychology, Neurophysiology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Healthy volunteer during “laser needle” EEG (electroencephalography) experiment in Graz, Austria (with written permission of the subject).

Written informed consent was obtained, and the investigations were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz (13-048, laser needle stimulation). The subject was not taking medications and had no neurological or psychological impairments. The volunteer was informed about the nature of the investigation, as far as the study design allowed, and the measurements were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Laser Needle Stimulation

Laser needle stimulation (Laserneedle GmbH, Berlin, Germany) allows the continuous stimulation of one or more acupuncture points on the body, the head, hands, or ears [2–14]. In this investigation, laser irradiation of 658 nm and 55 mW laser diodes was coupled into an optical fiber, and the laser needle was arranged at the distal end of this fiber. Due to coupling losses, the output power of the laser needles was reduced to 40 mW. The fiber core used in this study was about 500 μm in diameter. Stimulation frequency was 1 Hz. The method is described in detail in previous publications [2–14].

In order to have the laser pulses act as the sole stimulus to the average with the EEG (electroencephalography) recording system, each flash of the laser was accompanied by a 5 V pulse signal that triggered the average (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trigger realization, especially for this laser needle study.

As in further studies [1], control experiments were performed to eliminate the possibility that the evoked potential obtained after laser irradiation was influenced by timed artifacts arising from the interface between the laser instrument and the signal averaging system.

2.3. EEG Data Acquisition and Analysis

For the EEG investigations we used two USB biosignal amplifiers (g.USBamp generation 3.0) with 16 input channels each. For all channels, the simultaneous sample rate was set to 512 Hz (24-bit resolution) with a high-pass filter at 0.1 Hz, a low-pass filter at 100 Hz, and a notch filter at 50 Hz [15].

In the present investigation, we recorded 32 EEG channels. The electrodes were positioned on the cap according to the 10-20 system; the reference electrode was placed on the nose, and the grounding electrode was placed behind the ear above the mastoid process (compare Figure 1). Electrode impedance was less than 5 kOhm in each position [15].

The software package MATLAB was used for the analysis of the evoked potentials. After a visual inspection of the raw EEG data, trials containing artifacts were marked and omitted from further analysis. Afterwards the raw EEG was band pass filtered between 0.8 and 10 Hz. Finally, altogether about 600 trials were averaged from the processed EEG.

2.4. Control Measurement

In the control measurement, the optical stimulation of the laserneedle was visible for the healthy volunteer. To avoid a direct stimulation of the eye, the subject wore eye protection glasses, and the light source was located behind a screen.

2.5. Optical Acupuncture and Placebo Stimulation

The laser needles were placed on the skin at the Neiguan (PC6) acupuncture point bilaterally (Figure 3). PC6 is situated between the tendons of the palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis muscles, 2 cun proximal to the transverse crease of the wrist [16, 17]. The stimulation with red light (658 nm) was not felt by the subject. The volunteer has open eyes; however, the stimulation area was covered, and therefore the subject could not see whether the stimulation was on or off (compare Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Bilateral stimulation of the Neiguan acupoint (PC6).

3. Results

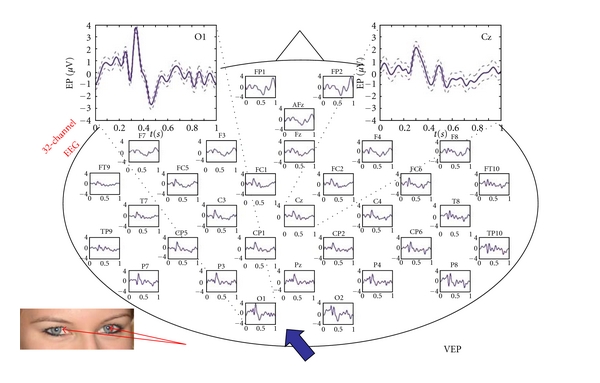

The result of the 32-channel visual evoked potential analysis is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

32 visual evoked potentials after visual input (indirect stimulation with laser light of 658 nm). Note the VEPs are present over the entire scalp with a dominance over the occipital (blue arrow) and central regions (X-axis: s; Y-axis: μV; mean ± SE).

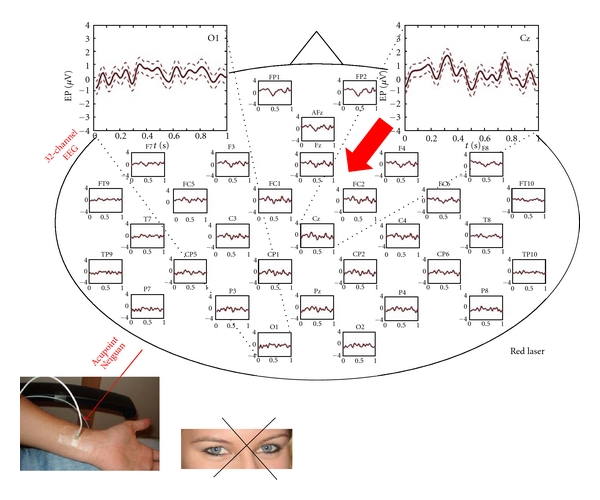

Figure 5 shows the same procedure; however the laser light stimulation at Neiguan acupuncture point was not visible and not perceptible for the subject (compare Figure 1). Only very small but reproducible evoked potentials are detectable, mainly over the central and frontal region.

Figure 5.

Reproducible evoked potentials after bilateral nonperceptible optical laser stimulation at the Neiguan acupuncture point. The evoked potentials are dominant over the central areas (red arrow) (X-axis: s; Y-axis: μV; mean ± SE).

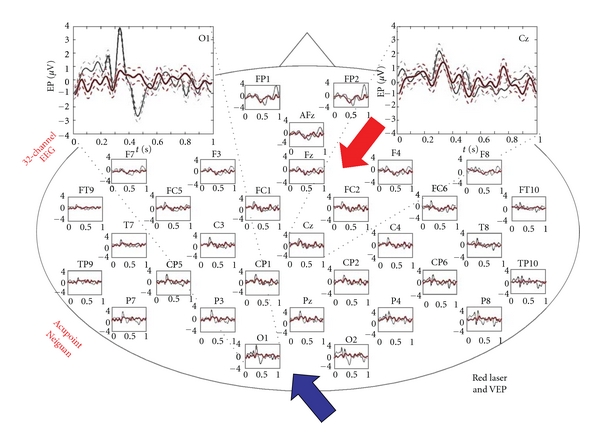

To facilitate comparison between the results of the visual evoked potentials and the laser-induced evoked potentials, the two measurements are plotted on top of each other in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Comparison of visual and laser-induced evoked potentials plotted with the same scale (X-axis: s; Y-axis: μV; mean ± SE).

4. Discussion

An irradiation, as from a laser, is not a stimulus found in nature. Lasers (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) allow brief pulses (μs to ms) with very fast rise time [18].

The laser needles used for acupuncture point stimulation in this study do not produce high temperatures; however, the penetration depth of the focused red laser light (658 nm) is about 3-4 cm [2]. Other experiments have indicated that brief high heating rate diode laser pulses can selectively activate myelinated Aδ fiber nociceptors in rats and produce pricking pain in humans, whereas for low heating rate, longer pulses can preferentially activate unmyelinated C fibers in rats and produce burning pain in humans [18–22]. There is no evidence whether these different pulse parameters will differentially activate fibers in humans.

In our present study, the laser needle stimulation (658 nm) was not felt by the subject. It is very interesting that this nonperceptible optical stimulation can lead to cortical responses. This finding appears to be unique in literature. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in scientific literature describing this phenomenon. Some reports concerning the effects on human brain EEG caused by manual needle stimulation at the PC6 acupuncture site are available [17]. These authors found that the frequency peaks in alpha band of 12 channels were more synchronized during and after acupuncture [17].

Conscious perception of stimuli requires two intact systems. The first one is, the specific input system which results in an evoked potential. The second one is, the unspecific system called ARAS, the ascending reticular activating system which was first investigated by Moruzzi and Magoun [23].

There is an example which is similar to the mechanism probably at work in our experiment; for example, during sleep, the ear is also in an activated state; auditory evoked potentials are possible although one does not consciously perceive the stimuli. Therefore it could be possible that laser stimulation modulates functional structures in the ascending reticular activating system.

Further studies with EEG and other neuromonitoring techniques like near infrared spectroscopy [24] and different stimulation methods (optical-cave VEP, electrical, mechanical) are in progress and absolutely necessary to confirm or refute the preliminary findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. W. Anderle, MD (former MD student at the Medical University of Graz, who also wrote her diploma thesis on a related topic), and Ms. H. Hiebel (student at the Department of Psychology, Karl-Franzens University Graz) for their help in the measurement preparation, Ms. Xin-Yan Gao, MD PhD (Associate Professor at the Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, and guest scientist with a Eurasia-Pacific Uninet scholarship at the TCM Research Center Graz, Medical University of Graz) for acupoint selection and application of the laser at the acupoint, and Ms. Ingrid Gaischek, MSc, for her support in manuscript preparation (Stronach Research Unit for Complementary and Integrative Laser Medicine, Research Unit of Biomedical Engineering in Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, and TCM Research Center Graz, Medical University of Graz). The authors also thank Prof. Gert Pfurtscheller, former Head of the Institute of Knowledge Discovery at Graz University of Technology, for the useful and stimulating discussions. The research activities are supported by Stronach Medical Group, the German Academy of Acupuncture (DAA) and the Department of Science of the City of Graz. The measurements are partly supported by Laserneedle GmbH and performed within the research areas “Sustainable Health Research” and “Neuroscience” at the Medical University of Graz. This paper is one of the first joint manuscripts within the recently installed platform BioTechMed.

References

- 1.Walker JB, Akhanjee LK. Laser-induced somatosensory evoked potentials: evidence of photosensitivity in peripheral nerves. Brain Research. 1985;344(2):281–285. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90805-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litscher G, Schikora D, editors. Laserneedle-Acupuncture. Science and Practice. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litscher G, Schikora D. Cerebral vascular effects of non-invasive laserneedles measured by transorbital and transtemporal Doppler sonography. Lasers in Medical Science. 2002;17(4):289–295. doi: 10.1007/s101030200042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litscher G, Rachbauer D, Ropele S, et al. Acupuncture using laser needles modulates brain function: first evidence from functional transcranial Doppler sonography and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Lasers in Medical Science. 2004;19(1):6–11. doi: 10.1007/s10103-004-0291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litscher G. Ten years evidence-based high-tech acupuncture—a short review of peripherally measured effects. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(2):153–158. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litscher G. Ten years evidence-based high-tech acupuncture—a short review of centrally measured effects (part II) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(3):305–314. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litscher G. Effects of laserneedle stimulation in the external auditory meatus on brainstem and very early auditory evoked potentials in humans. Neurological Research. 2006;28(8):837–840. doi: 10.1179/016164106X110373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litscher G. Bioengineering assessment of acupuncture, part 2: monitoring of microcirculation. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 2006;34(4):273–293. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litscher G. Bioengineering assessment of acupuncture, part 3: ultrasound. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 2006;34(4):295–325. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litscher G. Bioengineering assessment of acupuncture, part 4: functional magnetic resonance imaging. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 2006;34(4):327–345. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litscher G. Electroencephalogram-entropy and acupuncture. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2006;102(6):1745–1751. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000217188.71710.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litscher G. Infrared thermography fails to visualize stimulation-induced meridian-like structures. Biomedical Engineering Online. 2005;4(1, article 38) doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litscher G. Effects of acupressure, manual acupuncture and Laserneedle acupuncture on EEG bispectral index and spectral edge frequency in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2004;21(1):13–19. doi: 10.1017/s0265021504001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litscher G. Cerebral and peripheral effects of laser needle-stimulation. Neurological Research. 2003;25(7):722–728. doi: 10.1179/016164103101202237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderle W. Neurophysiologic and neurospectroscopic mapping-effects of acupuncture. Medical University of Graz; 2011. p. p. 52. Diploma thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stux G, Pomeranz B. Basics of Acupuncture. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang S, Chang ZG, Li SJ, et al. Effects of acupuncture at neiguan (PC 6) on electroencephalogram. Chinese Journal of Physiology. 2009;52(1):1–7. doi: 10.4077/cjp.2009.amg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzabazis AZ, Klukinov M, Crottaz-Herbette S, Nemenov MI, Angst MS, Yeomans DC. Selective nociceptor activation in volunteers by infrared diode laser. Molecular Pain. 2011;7, article 18 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greffrath W, Nemenov MI, Schwarz S, et al. Inward currents in primary nociceptive neurons of the rat and pain sensations in humans elicited by infrared diode laser pulses. Pain. 2002;99(1-2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuellar JM, Manering NA, Klukinov M, Nemenov MI, Yeomans DC. Thermal nociceptive properties of trigeminal afferent neurons in rats. Molecular Pain. 2010;6, article 39 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veldhuijzen DS, Nemenov MI, Keaser M, Zhuo J, Gullapalli RP, Greenspan JD. Differential brain activation associated with laser-evoked burning and pricking pain: an event-related fMRI study. Pain. 2009;141(1-2):104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzabazis A, Klyukinov M, Manering N, Nemenov MI, Shafer SL, Yeomans DC. Differential activation of trigeminal C or Aδ nociceptors by infrared diode laser in rats: behavioral evidence. Brain Research. 2005;1037(1-2):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moruzzi G, Magoun HW. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1949;1(1–4):455–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litscher G, Bauernfeind G, Gao X, et al. Battlefield acupuncture and near-infrared spectroscopy-miniaturized computer-triggered electrical stimulation of battlefield ear acupuncture points and 50-channel near-infrared spectroscopic mapping. Medical Acupuncture. 2011;23(4):263–270. [Google Scholar]