Abstract

Context

Inhalation of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is associated with adverse respiratory and cardiovascular effects. A major fraction of PM2.5 in urban settings is diesel exhaust particulate (DEP), and DEP-induced lung inflammation is likely a critical event mediating many of its adverse health effects. Oxidative stress has been proposed to be an important factor in PM2.5-induced lung inflammation, and the balance between pro- and antioxidants is an important regulator of this inflammation. An important intracellular antioxidant is the tripeptide thiol glutathione (GSH). Glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) carries out the first step in GSH synthesis. In humans, relatively common genetic polymorphisms in both the catalytic (Gclc) and modifier (Gclm) subunits of GCL have been associated with increased risk for lung and cardiovascular diseases.

Objective

This study was aimed to determine the effects of Gclm expression on lung inflammation following DEP exposure in mice.

Materials and methods

We exposed Gclm wild type, heterozygous, and null mice to DEP via intranasal instillation and assessed lung inflammation as determined by neutrophils and inflammatory cytokines in lung lavage, inflammatory cytokine mRNA levels in lung tissue, as well as total lung GSH, Gclc, and Gclm protein levels.

Results

The Gclm heterozygosity was associated with a significant increase in DEP-induced lung inflammation when compared to that of wild type mice.

Discussion and conclusion

This finding indicates that GSH synthesis can mediate DEP-induced lung inflammation and suggests that polymorphisms in Gclm may be an important factor in determining adverse health outcomes in humans following inhalation of PM2.5.

Keywords: Diesel exhaust particulate, lung inflammation, glutathione, oxidative stress, glutamate cysteine ligase

Introduction

The inhalation of fine ambient particulate matter (PM2.5) has long been associated with increased risk of adverse pulmonary and cardiovascular events such as the exacerbation of asthma symptoms, airway inflammation, myocardial ischemia, and myocardial infarction (MI) (Dockery et al., 1993; Hoek et al., 2001; Hoek et al., 2002; Pope et al., 2002). Ambient PM2.5 has a wide range of sources, but in many urban areas, the majority of PM2.5 is derived from diesel exhaust particulate (DEP) (Lewtas, 2007). Thus, DEP has been widely used as a model toxicant to investigate PM2.5 toxicity. The pathophysiological effects observed with controlled human and animal DEP exposures are wide ranging and include neutrophilic inflammation (Nordenhäll et al., 2000; Salvi et al., 1999; Stenfors et al., 2004) and activated antioxidant response pathways (Mudway et al., 2004; Pourazar et al., 2005) within the airway. Many researchers have suggested that PM2.5-induced pulmonary inflammation is influencing observed systemic changes such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and compromised vasomotor function (Stenfors et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2008; Törnqvist et al., 2007). DEP is largely considered a prooxidant and it is widely believed that it produces pulmonary inflammation at least in part by causing oxidative stress following particle uptake by alveolar macrophages and respiratory epithelial cells (Banerjee et al., 2009; Finkelstein et al., 1997; Pourazar et al., 2005).

Glutathione (GSH) is an antioxidant tripeptide that can reach millimolar levels within certain cells such as hepatocytes. The GSH plays a critical role in maintaining intracellular redox status with GSH-dependent enzymes including GSH reductase and GSH peroxidases. The GSH is synthesized in a two-step process: (1) glutamate and cysteine are combined together to form γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-GC), catalyzed by glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) and (2) γ-GC is combined with glycine to form GSH, catalyzed by glutathione synthase (GS) (Franklin et al., 2009). The rate-limiting step in GSH synthesis is the formation of γ-GC by GCL. The GCL is a two-subunit enzyme composed of modifier (Gclm) and catalytic (Gclc) subunits and it has been previously demonstrated that Gclm null (Gclm−/−) mice are dramatically compromised in GCL activity and GSH synthesis, and thus provide an excellent tool to investigate the role of GSH in mediating oxidative stress and toxicant induced injury (Botta et al., 2008; McConnachie et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2002).

Several prior studies have examined the role of the transcription factor Nrf2, which governs multiple antioxidant pathways, as a susceptibility factor for DEP-induced lung injury and inflammation. The Nrf2 is an important determinant of Gclm and Gclc expression (Bea et al., 2003; Bea et al., 2009). While oxidative stress and Nrf2-regulated antioxidant status have been pointed to as major factors mediating the observed responses with in vivo exposures to DEP (Li et al., 2010; Li et al., 2008), there have been no studies published to date specifically investigating susceptibility to DEP-induced inflammation in an animal model of compromised GSH synthesis. The GSH synthesis and redox status have been implicated in the pathogenesis of many clinical conditions. In particular, relatively common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) present within the 5′ promoter regions of Gclm and Gclc have been associated with increased risk of MI, compromised vascular reactivity, and decreased lung function (Koide et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2002; Nakamura et al., 2003; Siedlinski et al., 2008). Nakamura et al. (2002) demonstrated that the presence of a SNP within only a single allele of Gclm (~20% of control group) was associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of MI in humans, providing strong support for the hypothesis that Gclm expression, GCL activity, and GSH are important factors in mediating the risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition to vascular effects, it was demonstrated that SNPs within the 5′ promoter region of Gclc are associated with accelerating the decrease in lung function resulting from smoking (Siedlinski et al., 2008). Although these SNPs within Gclc were not found to be associated with increased risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) within a smoking cohort (Chappell et al., 2008), observations that these SNPs accelerate lung function decline in smokers suggest that GSH and GCL activity are important factors that influence pulmonary function under conditions of oxidative stress. Due to a relatively high frequency of these polymorphisms and the relatively large effect on health outcome, there is a need for increased research on the potential of these SNPs to produce gene-environment interactions following exposure to common toxicants, including PM2.5. Although Gclm−/− mice have a dramatic reduction in GSH, these mice are not overtly sensitive to all agents that produce oxidative stress. It was recently demonstrated that many alternative antioxidant enzymes are induced in the livers of these mice, and this was associated with protection from steatohepatitis induced by a methionine and choline deficient diet (Haque et al., 2010). Similarly, Gclm−/− mice are not particularly sensitive to ozone-induced lung injury, apparently for similar reasons (Johansson et al., 2010). However, Gclm heterozygous (Gclm−/+) mice do not have a dramatic reduction in GSH, and thus would not be expected to have upregulated many compensatory antioxidant enzymes that could provide protection from oxidant injury. In humans having the —588C/T polymorphism within the 5′ promoter region of Gclm, the total plasma GSH levels are not dramatically reduced (Nakamura et al., 2002), but it is possible that these people have a compromised ability to upregulate Gclm expression during periods of oxidative stress. This condition is highly similar to that of Gclm−/+ mice, and thus this mouse model is a potentially valuable to investigate susceptibility to environmental toxicants where compromised ability to upregulate Gclm may predispose to oxidative stress-induced disease. In this report, we exposed C57BL/6 Gclm wild type (WT), Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice to DEP via intranasal instillation. Animals were sacrificed 6 h after instillation, and a series of measures were used to gauge the degree of lung inflammation. We hypothesized that although Gclm−/+ mice will not have dramatically lower GSH, they will be more susceptible to injury due to compromised ability to fully upregulate Gclm expression in response to DEP exposure. In addition, we hypothesized that Gclm−/− mice may be still more sensitive to DEP than Gclm WT mice, but not overtly sensitive as they have compensated for the decrease in GSH by upregulating many alternative antioxidant enzymes.

Materials and methods

DEP collection

The PM2.5 was collected from a Cummins diesel engine operating under 75% maximum load. Particles were collected from the outflow duct at the University of Washington diesel exhaust exposure facility. The fine particulate matter size distributions are very similar to aged diesel exhaust particles a few hundred meters away from a major roadway; these particles and exposure facility characteristics have been previously described (Gould et al., 2008). The DEP were suspended in DMSO (2.5%) then further diluted in PBS (97.5%) to 10 mg/mL. These DEP stock solutions were sonicated for 1 min prior to all dosing. All control animals were dosed with an equivalent volume of the 2.5% DMSO, 97.5% PBS solution as a solvent control.

Mice and intranasal instillation

The Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice backcrossed for at least 10 generations onto the C57BL/6 background were bred and housed in a modified specific pathogen free (SPF) vivarium at the University of Washington. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male littermates were genotyped, as previously described (McConnachie et al., 2007), and randomly assigned to either saline or DEP treatments. Mice between the ages of 8 and 12 weeks were subjected to light anesthesia by I.P. injection of 0.01 mL/g body weight of a 0.44 mg/mL Xylazine, 6.5 mg/mL Ketamine solution in sterile saline. During anesthesia, 10 μL of a 10 mg/mL solution of DEP was slowly pipetted into each nostril for a total dose of 20 μL/mouse (~200 μg DEP, ~6.7 mg/kg in a 30 g mouse).

Bronchial alveolar lavage, cell staining, and flow cytometry

Mice were sacrificed by CO2 narcosis followed by cervical dislocation 6 h after being exposed to DEP. This 6 h time-point was chosen as it allowed us to assess the acute inflammatory response (e.g. neutrophil influx into the alveolar space), as well as changes in mRNA expression for various stress responsive genes. The peritoneal, thoracic, and cervical areas were carefully opened and the trachea was surgically isolated. A small incision was made in the trachea just below the larynx and an 18 G catheter attached to a 1 mL syringe was inserted to perform the lavage. The PBS was used as the lavage medium, and following catheter insertion into the trachea, 1 mL of PBS was slowly instilled into the lungs and subsequently withdrawn. This rinsing action was repeated 3 × per wash, and three 1 mL washes were performed for each mouse. The lavage sample from the first wash was collected independently and placed into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, while the lavage from the second and third washes were combined. Cells in the lavage samples were then pelleted by centrifugation at 200 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant from the first wash was collected for cytokine analysis, whereas the supernatant from the second and third washes was discarded. Cells from all three washes were combined, treated with a red blood cell lysis buffer (ammonium chloride lysing solution; 1.5 M NH4Cl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM disodium EDTA, in dH2O) at room temperature for 5 min, blocked for 30 min with 1% bovine serum albumin and 5% rat serum, and then subsequently stained for 15 min with primary antibodies directed against F4/80 antigen conjugated with Alexafluor 488 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA; Cat# 53–4801-80) and biotinylated anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly6C (Gr1) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA; Cat# 108404). Subsequently, streptavidin Alexafluor 350 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; Cat# S11249) was added. Cells were analyzed on a Beckman-Coulter Altra fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL, USA), and 5000 cells were examined for each animal. Neutrophils were identified as cells expressing low F4/80 and high Gr1 levels as indicated by green versus blue fluorescence intensity, respectively. A total of 62 mice were used in the assessment of neutrophil influx (13 WT-PBS, 10 WT-DEP, 12 Gclm−/+-PBS, 10 Gclm−/+-DEP, 8 Gclm−/−-PBS, and 9 Gclm−/−-DEP).

RNA isolation and fluorogenic 5′ nuclease-based assay and quantitative RT-PCR

Lung tissue from each animal was collected from the base of the inferior lobe of the right lung. Tissue samples were placed in RNA stabilizing solution (Trizol; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and immediately homogenized. The RNA isolation was subsequently carried out using a Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The Center for Ecogenetics Functional Genomics Laboratory at the University of Washington developed fluorogenic 5′ nuclease-based assays to quantitate the mRNA levels of specific genes. Briefly, reverse transcription was performed according to the manufacturer’s established protocol using total RNA and the SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For gene expression measurements, 2 μL of cDNA containing eluant were included in a PCR reaction (12 μL final volume) that also consisted of the appropriate forward (FP) and reverse (RP) primers, probes, and TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). The PCR primers and the dual-labeled probes for the genes were designed using ABI Primer Express version1.5 software (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). The expression levels of several genes were assessed using the ABI inventoried TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) mix according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplification and detection of PCR amplicons were performed with the ABI PRISM 7900 system (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) with the following PCR reaction profile: 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, and 62°C for 1 min. The β̃-actin amplification plots derived from serial dilutions of an established reference sample were used to create a linear regression formula in order to calculate expression levels, and β̃-actin gene expression levels were utilized as an internal control to normalize the data. Six mice from each genotype and treatment were used to analyze differential expression of the selected genes.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cytokine measurement

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples from the first wash were analyzed for IL6 and TNFα concentration by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using “Ready-Set-Go!” ELISA kits following the manufacturer protocol (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA; Cat#’s 88–7064-22 and 88–7324-22). Moreover, 100 μL of sample were used for each measurement, which were performed in duplicate. Six mice from each genotype and treatment were used for cytokine analysis.

Myeloperoxidase ELISA

Lungs were homogenized in tissue lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with a proteinase inhibitor cocktail pill (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), aliquoted, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Wells of a 96-well plate were incubated with capture antibody overnight at room temperature (1 μg/mL anti-human/mouse myeloperoxidase (MPO), AF3667, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and then washed three times with PBS and 0.05% Tween (PBST). Wells were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 1 h, washed with PBST, and incubated with sample or standard (0.4 to 250 ng/mL) overnight at 4°C. Wells were again washed with PBST and then incubated with detection antibody (0.25 μg/mL anti-mouse MPO, HM1051BT, Hycult Biotechnology, B.V., Uden, The Netherlands). After 2 h, wells were washed with PBST and then incubated with Streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 20 min. Wells were washed with PBST before TMB Substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well and incubated for 5–20 min. About 100 μL of a 0.5 M solution of H2SO4was used to stop the reaction, and plates were read at 450 nm using a Synergy 4 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Six mice from each genotype and treatment were used for MPO analysis.

Metalloproteinase activity

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) activity was measured as previously reported (Gill et al., 2010). Briefly, the OmniMMP™ fluorogenic substrate (P-126, Biomol International, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) was used to analyze total metalloproteinase activity in lung homogenates. Samples (25 μL) were added to 96-well plates and warmed to 37°C. Substrate was added to each well, and the plate was read immediately (λex328; λem393) and then again at 1.5, 3, 6, 12, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min with a Synergy 4 (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The increase in fluorescence was plotted against time, and the slope of the line, which indicates metalloproteinase activity, determined using GraphPad Prism for Macintosh version 4.0c (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Six mice from each genotype and treatment were used for MMP analysis.

GSH and Gclm/Gclc protein level

The Gclm and Gclc protein levels were detected with the use of rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against ovalbumin conjugates of peptides specific to each subunit, using previously described procedures (Thompson et al., 1999). The optical density of Gclm and Gclc specific bands on X-ray films were determined by Image J software and normalized to β-actin levels in six animals from each genotype and treatment. For total GSH measurements, clarified tissue homogenates prepared in TES/SB (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM serine, and 1 mM boric acid) were diluted 1:1 with 10% 5-sulfosalicylic acid, incubated on ice for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 15,600 × g in a microcentrifuge for 2 min to obtain deproteinated supernatants. About 25 μL aliquots of the supernatants were added to a 96-well black microtiter plate in triplicate followed by addition of 100 μL of 0.2 M N-ethylmorpholine/0.02 M NaOH. Following the addition 50 μL of 0.5 N NaOH, GSH was derivatized by the addition of 10 μL of 10 mM naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde (NDA). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 30 min and the fluorescence intensity of NDA–GSH conjugate was measured at λex472 and λem528, and quantified by interpolation on a standard curve constructed with NDA-conjugated GSH in TES/SB:10% sulfosalicylic acid (1:1). A total of 58 mice were used in the assessment of lung GSH content (9 WT-PBS, 8 WT-DEP, 13 Gclm−/+-PBS, 15 Gclm−/+-DEP, 6 Gclm−/−- PBS, and 7 Gclm−/−-DEP).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences were determined by ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s post-hoc test. All error bars in figures represent SEM; *, **, *** = Significant difference from the matched control at p-values of <0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

Results

Intranasal instillation of DEP

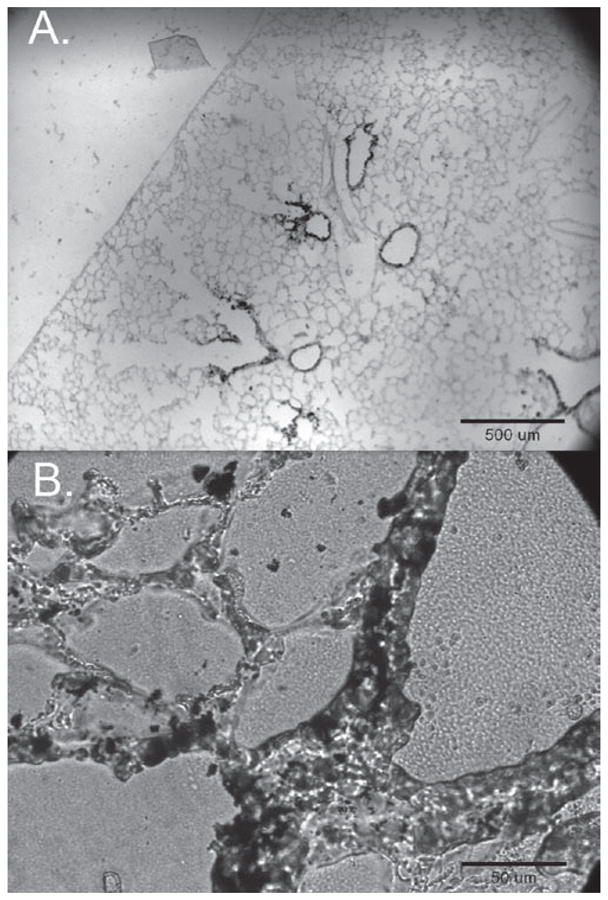

In order to evaluate the ability of the DEP used in this study to reach the airways and lungs of mice after intranasal instillation, 10 μL of a 10 mg DEP/mL solution was instilled into each nostril of three wild-type C57BL/6 mice. One hour later, mice were euthanized, a tracheotomy was performed, and 1 mL of Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA, USA) was used to inflate the lungs. Both lungs were then removed from the animal and embedded in OCT and frozen on dry ice. Cross sections of these lungs (7 μm thick) were cut on a cryomicrotome and mounted on a glass slide for imaging. Images from lung cross sections clearly indicate that intranasally instilled DEP reached the airways and lungs of mice and were freely available to interact with resident cells (Figure 1A). Although most of the DEP was found in the larger airways, smaller particle agglomerates were able to reach the alveolar spaces (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Images of lung cross sections 1 h after intranasal instillation of DEP (10μL of 10mg/mL DEP per nostril) in WT C57bl6 mice. Panels A and B are a 4x image and a 40x image of a single cross section from the upper region of the right lung.

Bronchial alveolar lavage fluid analysis

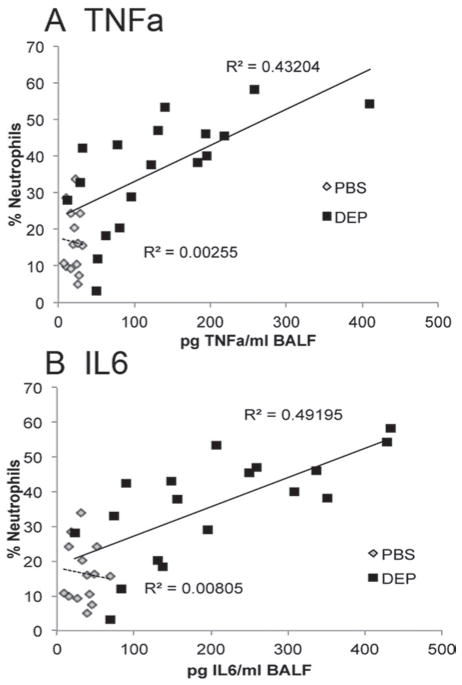

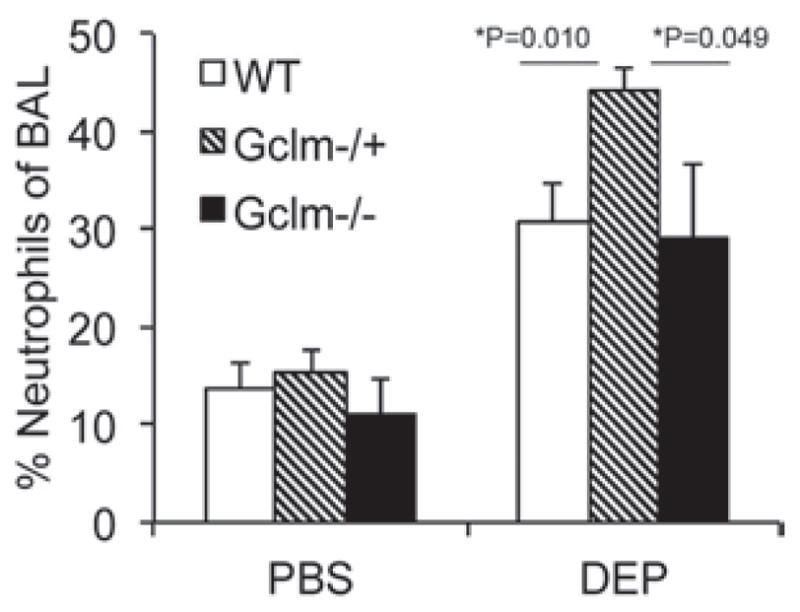

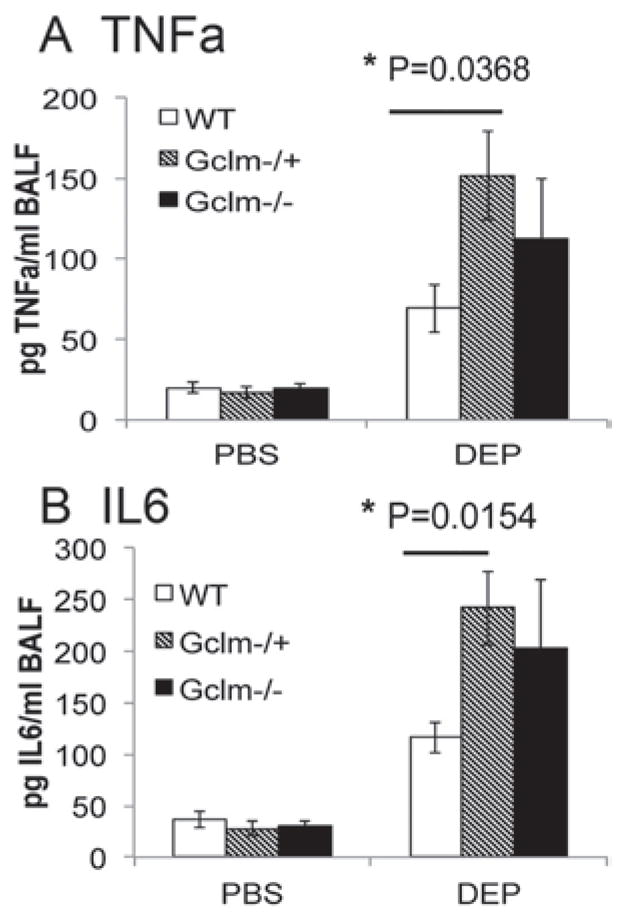

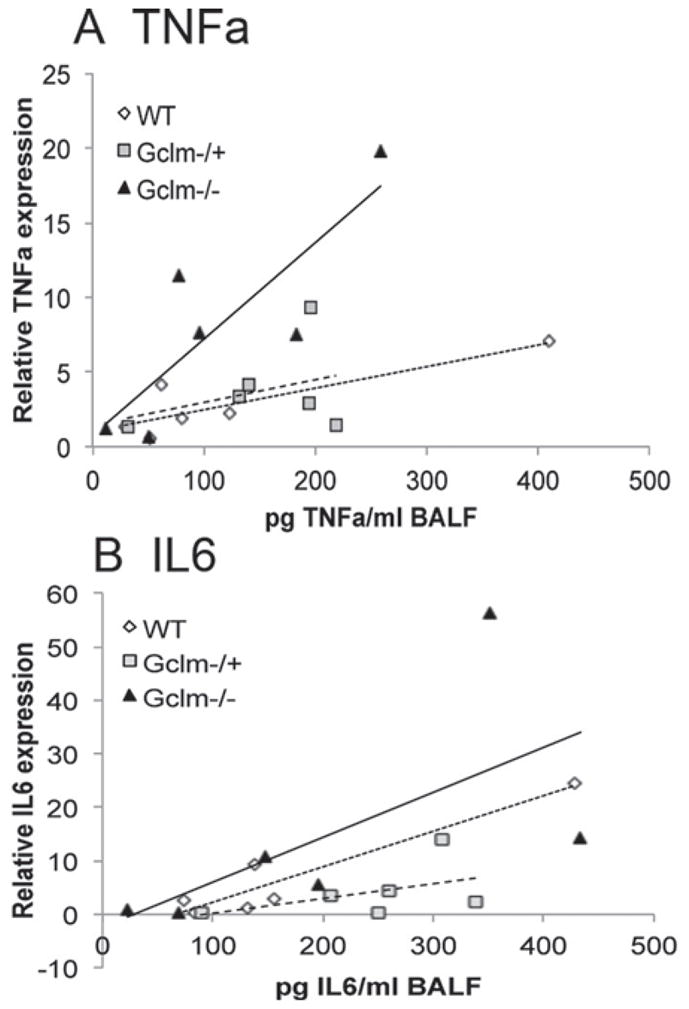

To determine if Gclm modulation and GSH synthesis influences the pulmonary inflammatory response following intranasal instillation of DEP, Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice were put under light anesthesia and 10 μL of a 10 mg DEP/mL solution or PBS was instilled into each nostril. Six hours after the DEP instillation, mice were euthanized by CO2-narcosis followed by cervical dislocation. Measurement of neutrophil influx into the airways by flow cytometric analysis of cells present in the BALF indicated that DEP instillation caused a robust increase in the numbers of neutrophils relative to PBS treated mice for all three genotypes (Figure 2). Although we hypothesized that Gclm−/− mice would be more sensitive to DEP instillation than WT mice, our results indicate that Gclm−/− mice do not respond any differently than WT mice with regard to neutrophil influx. Alternatively, as we hypothesized, Gclm−/+ mice were significantly more sensitive to the treatment (Figure 2). There were no significant differences for the percentage of neutrophils among PBS-treated WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice (14%, 15%, and 12% neutrophils, respectively), but the percentage of neutrophils reached an average of 44% in Gclm−/+ DEP-treated mice, roughly 15% higher than that observed for both Gclm WT and Gclm−/− mice treated with DEP. Although FACS analysis showed that Gclm−/+ mice were more sensitive to DEP-induced neutrophil influx compared to Gclm WT and Gclm−/− mice, the production of inflammatory cytokines in the lungs of DEP-exposed mice was also a concern since these factors can influence further downstream events. Two cytokines that play a role in downstream events are TNFα and IL6. Therefore, we analyzed TNFα and IL6 concentrations in the BALF of PBS- and DEP-treated Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice. Consistent with our previous finding of increased sensitivity to neutrophil influx, TNFα and IL6 concentrations within BALF were significantly higher in DEP-treated mice than PBS-treated mice for all three Gclm genotypes (Figure 3). Also consistent with our previous findings, DEP-treated Gclm−/+ mice had significantly higher BALF TNFα and IL6 compared to DEP-treated WT mice (Figure 3). Although not significantly different from either the DEP-treated WT or Gclm−/+ mice, DEP-treated Gclm−/− mice had an intermediate response as the levels of both TNFα and IL6 were between DEP-treated WT and DEP-treated Gclm−/+ mice (Figure 3). The TNFα and IL6 BALF concentrations were very low in all three genotypes of the PBS-treated mice, where averages of TNFα concentrations were less than 20 pg/mL and averages of IL6 concentrations were roughly 30 pg/mL. In comparison, DEP treatment produced an increase in TNFα to roughly 70, 150, and 120 pg TNFα/mL in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice, respectively. The IL6 concentrations increased to 120, 240, and 220 pg IL6/mL in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice, respectively. These robust responses indicated that DEP instillation produced overt pulmonary inflammation and that Gclm−/+ mice were more sensitive to DEP-induced inflammation. To determine if there was a correlation between neutrophil influx and cytokine levels in the BAL, we performed regression analysis (Figure 4). This analysis indicated a strong correlation between the percentage of neutrophils and cytokine concentrations for both TNFα and IL6 in DEP-treated mice (R2 value = 0.432 and 0.492 for TNFα and IL6, respectively). Although this correlation was strong for DEP-treated animals, there was no correlation for PBS-treated animals (R2 values <0.01) (Figure 4). These data indicated that although there was some variability for the percentage of neutrophils in the PBS-treated mice, this variability was not associated with an increase in TNFα and IL6 production. Taken together, these data demonstrate that increases in TNFα and IL6 were only found in DEP-treated animals and that the mild neutrophil influx observed in PBS-treated mice was not associated with increased cytokine production.

Figure 2.

The FACS analysis of percentage neutrophils (F4/80lo/Gr1hi) from 5000 cells collected in BAL in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The n values for treatments are: Gclm WT, N = 13-PBS: 10-DEP, Gclm−/+, n = 12-PBS: 10-DEP and Gclm−/−, n = 8-PBS: 9-DEP. Error bars represent SEM; * = Significant difference at p-values of <0.05.

Figure 3.

Concentration of inflammatory cytokines TNFα (3a) and IL6 (3b) in BAL fluid in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The n = 6 for all genotypes and treatments. Error bars represent SEM; * = Significant difference at p-values of <0.05.

Figure 4.

Linear regression analysis between percentage neutrophils and BAL fluid concentration of inflammatory cytokines TNFα (4a) and IL6 (4b) within all genotypes 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The R2 values are given for regression performed within treatment condition.

Gene expression analysis of lavaged lung tissue

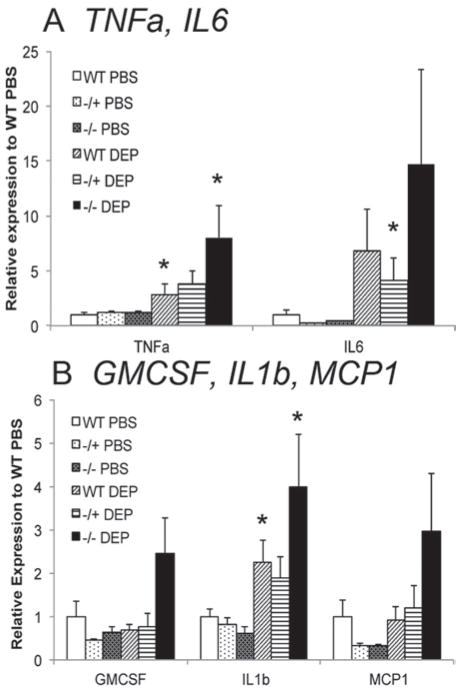

To further investigate whether Gclm genotype can modulate DEP-induced lung inflammation, we analyzed the expression of five proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs (TNFα, IL6, GM-CSF, IL1β, and MCP1) in PBS- and DEP-treated Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mouse lung tissues by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR). As mentioned above, assessment of BALF TNFα and IL6 proteins demonstrated that Gclm−/+ mice were more sensitive to DEP treatment than WT mice, whereas Gclm−/− mice appeared to have an intermediate response (Figure 3). However, mRNA expression levels for these inflammatory cytokines were not consistent with this trend. Rather, Gclm−/− mice appeared to be most sensitive following DEP treatment across all genes analyzed, although this only approached statistical significance (p = 0.06; Figure 5). Overall, DEP-treated Gclm−/− mice had nearly a two-fold increase in expression compared to Gclm−/+ or WT DEP-treated mice for all genes analyzed, and this response was particularly robust for TNFα and IL6. Whereas DEP treatment produced roughly a four-fold increase in TNFα expression in Gclm−/+ mice relative to WT PBS-treated mice, DEP-treated Gclm−/− mice had an eight-fold increase. The expression of IL6 was increased to seven- and four- fold over WT-PBS mice for DEP-treated Gclm WT and Gclm−/+ mice, respectively, while DEP-treated Gclm−/− mice had nearly a 15-fold increase. Although this increase in IL6 in Gclm−/− mice was not significant due to high variability, the trend across all genotypes indicates that Gclm−/− mice are most sensitive to DEP with respect to induction of inflammatory cytokine mRNAs. To further examine the relationship between lung tissue mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory cytokines found in the BALF, we performed a linear regression analysis comparing BALF TNFα and IL6 protein levels and TNFα and IL6 mRNA expression in DEP-treated Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice relative to WT PBS-treated controls (Figure 6). We stratified linear regression based on genotype, and found that although there is a positive correlation between gene expression and BALF cytokines across all genotypes, the slope for DEP-treated Gclm−/− mice is dramatically steeper for TNFα (Figure 6A), possibly indicating that a greater amount of TNFα mRNA expression was required in these mice to reach a similar BALF TNFα concentration. The linear slopes for the TNFα correlation with DEP-treated Gclm WT and Gclm−/+ mice were nearly identical, further pointing out the uniqueness of Gclm−/− mice. Although the trend was similar when the analysis was performed for IL6, the trend was not as dramatic (Figure 6B). Together, these data suggest that Gclm−/− mice were unable to effectively translate the mRNAs for these proinflammatory cytokines, at least at the time point measured, and under these DEP exposure conditions.

Figure 5.

Real-time PCR assessment of mRNA levels for TNFα, IL6, (5a) and GMCSF, IL1β, and MCP1 normalized to β-actin in the lung of Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The n = 6 for all genotypes and treatments. Error bars represent SEM; * = Significant difference at p-values of <0.05.

Figure 6.

Linear regression analysis between real-time PCR assessment of mRNA levels for TNFα (6A) and IL6 (6B) normalized to β-actin and BAL fluid concentration of inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL6 in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after DEP intranasal instillation.

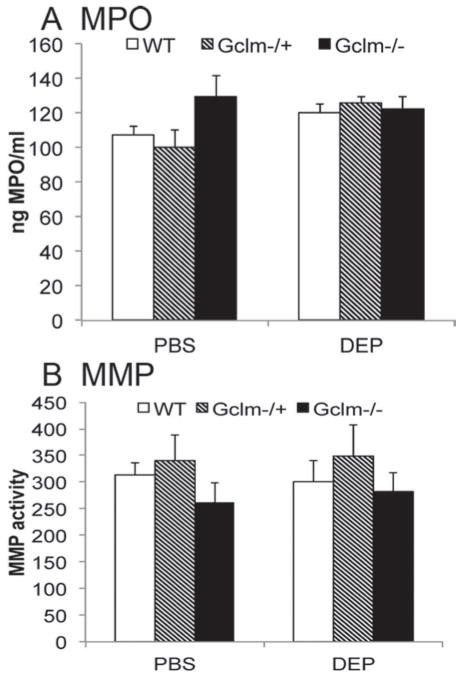

Investigation of MMP and MPO within lavaged lung tissue

The observation that Gclm−/+ mice are more sensitive to DEP-induced inflammation compared to Gclm WT and Gclm−/− mice is important as it further indicates that GCL activity and GSH synthesis may influence inflammatory responses following environmental diesel exhaust exposure. Although we hypothesized that modulation of Gclm would lead to increased sensitivity, we believed that Gclm−/− mice may not be the most sensitive as they likely have compensatory upregulation of alternative antioxidant enzymes. Our findings indicate that this was probably true with regard to neutrophil influx and cytokine production, but interestingly, gene expression profiles of five proinflammatory cytokines suggested that null mice might be more sensitive to DEP treatment. Furthermore, the correlation between TNFα gene expression and BALF TNFα concentration suggested there was an altered relationship between lung tissue gene expression and subsequent BALF cytokine concentrations in these mice. These findings suggested that in Gclm−/− mice, the ability to mount an inflammatory response and recruit neutrophils to the lung and translocate from the lung interstitium into the alveolar space was compromised such that they are unable to form and/or secrete these cytokines. The MMP activity can promote neutrophil influx by shedding surface proteins and affecting chemokine activity and presentation (Gill & Parks, 2008). Because MMP activity can be regulated by oxidation, and because overt oxidation leads to inactivation of some MMPs (Fu et al., 2001), we hypothesized that Gclm−/− mice may have compromised metalloproteinase activity, and that even though neutrophils may have been recruited to the lung they might be incapable of translocating into the alveolar space. Thus, we analyzed MPO protein level of homogenized lung tissue as a surrogate marker of neutrophil content (Figure 7A). We also determined if Gclm genotype influenced metalloproteinase activity to see if it might explain the decrease in neutrophil response seen in Gclm−/− mice following DEP treatment (Figure 7B). We found no significant differences in MPO level or total metalloproteinase activity, irrespective of genotype or DEP treatment. There was a suggestion of a genotype effect across both treatments, in that Gclm−/− mice had lower metalloproteinase activity, while Gclm−/+ mice had higher metalloproteinase activity (Figure 7B), but this trend was minor if present at all. Although not a significant effect, if this trend is real, it would be consistent with our findings of elevated neutrophil influx into the lungs of Gclm−/+ mice and lower neutrophil influx into the lungs of Gclm−/− mice.

Figure 7.

The MPO protein level (A) and MMP activity (B) in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The n = 6 for all genotypes and treatments. Error bars represent SEM.

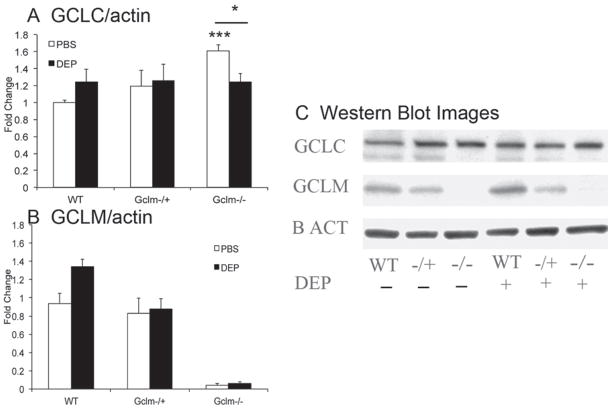

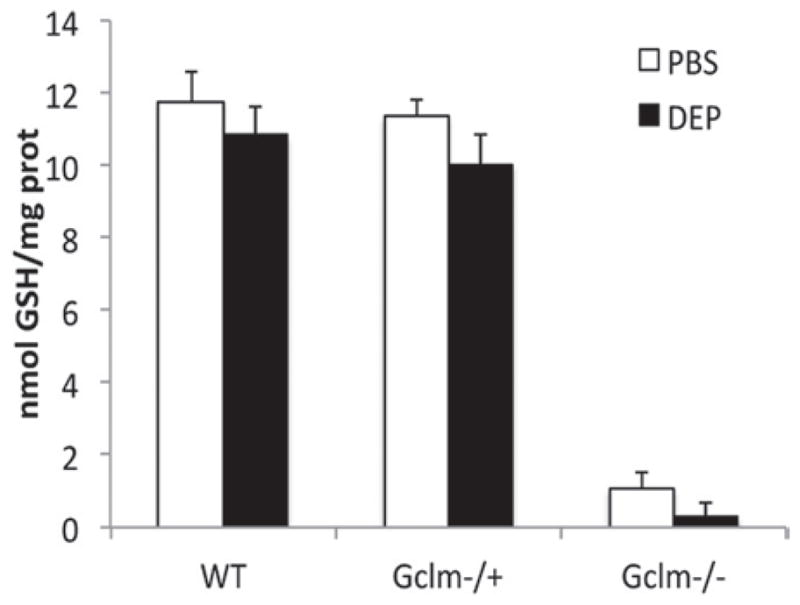

Analysis of total lung GSH and Gclm/Gclc protein levels

Because oxidative stress is a critical component of DEP-induced pulmonary inflammation, it is likely that the levels of intracellular antioxidants, such as GSH, play a major role in mediating such effects. To determine if total GSH and its regeneration are influenced by DEP treatment, we measured total GSH in lung homogenates from Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice. Consistent with previously reported values (McConnachie et al., 2007), we found that total lung GSH content in PBS-treated mice was approximately 90% and 5% of WT mice for Gclm−/+ and Gclm−/− mice, respectively (Figure 8). These data illustrate that under non-stressed conditions, complete deficiency in Gclm results in severely compromised GSH synthesis, whereas one copy of Gclm is sufficient to maintain relatively normal GSH levels. Across all genotypes of the DEP-treated mice there was a suggestion that DEP causes a slight reduction in total GSH, but these differences only approached significance (p = 0.08; Figure 8). The Gclm−/− mice had even lowered GSH levels after DEP treatment, nearly eliminating any available GSH with levels beneath the limit of detection of our assay. The observation that there is little change in whole lung GSH level following DEP treatment in WT and Gclmmice may suggest that alteration in GSH levels in the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) may be of more significance. To investigate the levels of Gclc and Gclm proteins following DEP treatment in both PBS- and DEP-treated WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice, we analyzed the expression of these proteins by western immunoblot (Figure 9). As previously reported (McConnachie et al., 2007), Gclc protein is elevated in Gclm−/− mouse lung (Figure 9A), and interestingly, DEP treatment produced a significant decrease in the Gclc protein. Although DEP treatment did not produce a significant effect on Gclc in either WT or Gclm−/+ mice, there was a suggestion that Gclc was slightly increased in the WT mice (p = 0.10), but not in the Gclm−/+ mice. Regarding Gclm protein levels, we confirmed that Gclm was not present in the Gclm−/− mice. Similar to the response seen with Gclc, there is a suggestion of an increase in Gclm in WT mice (p = 0.09) with DEP treatment compared to the PBS control, but in Gclm−/+ mice, Gclm expression was not altered (Figure 9B).

Figure 8.

Total GSH level in whole lung homogenate in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation. The n values for treatments are: Gclm WT, n = 9-PBS: 8-DEP, Gclm−/+, n = 13-PBS: 15-DEP, and Gclm−/−, n = 6-PBS: 7-DEP. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 9.

Total GCLC and GCLM protein levels normalized to β-actin measured by western blot in Gclm WT, Gclm−/+, and Gclm−/− mice 6 h after either PBS or DEP intranasal instillation; n = 6 for all genotypes and treatments. Error bars represent SEM; * = Significant difference from the PBS-treated WT control at p-value of <0.05; *** = Significant difference between Gclm−/− PBS and DEP treated mice at p-value of < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that genetic alteration of the GSH synthesis gene Gclm can exacerbate the inflammatory response of the lung following intranasal instillation of DEP. The dose of 200 μg DEP was chosen in order to produce an inflammatory response in the lung, and to be consistent with other studies investigating pulmonary inflammation following instillation of particulate matter into the respiratory tract of mice (Happo et al., 2010; Yokota et al., 2008). Although this dose is comparatively high relative to what might be expected for ambient exposures in humans, it does allow for a comparative assessment of the role of Gclm in mediating DEP-induced lung inflammation in mice.

Previous studies have indicated that DEP induces lung inflammation in part via oxidative stress and that GSH plays an important role in mediating this inflammatory response (Banerjee et al., 2009). Although our study failed to directly support this contention in that we did not observe significant DEP-induced GSH depletion in WT or Gclm−/+mice, or exacerbated inflammation in already GSH-depleted Gclm null mice, the finding that Gclm heterozygosity exacerbates DEP-induced lung inflammation does support the hypothesis that Gclm can influence the inflammatory response to DEP. It is reasonable to suggest that this is likely mediated via compromised GCL activity and GSH synthesis, although alternative mechanisms cannot be ruled out. Regardless of mechanism, as Gclm is highly polymorphic in people, our study provides additional evidence that Gclm may be an important gene influencing diesel exhaust-induced lung inflammation in humans.

Short-term periods of elevated PM2.5 have been associated with a greater frequency of emergency room visits (Katsouyanni et al., 1997; Peters et al., 1997; Peters et al., 2001; Seaton et al., 1995; Zanobetti et al., 2004), and although many of these visits are due to the exacerbation of existing asthma symptoms, these reports have indicated that PM2.5 exposure is associated with acute cardiovascular events such as MI and myocardial ischemia. It has long been demonstrated that the elevation of systemic and vascular inflammation has a major impact on vascular function and has been suggested to be a strong influencing factor for the risk of MI and myocardial ischemia. In particular, the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα has been demonstrated to influence vascular reactivity by activation of the superoxide producing NADPH oxidases within the vasculature (Gao et al., 2007). Since oxidative stress plays a role in PM2.5-induced lung inflammation, it is likely these local inflammatory factors can influence systemic vascular function by the induction of vascular oxidative stress. Individuals that are sensitive to PM2.5- induced inflammation due to compromised antioxidant synthesis will likely be at increased risk for these adverse cardiovascular events.

Our finding that Gclm heterozygosity increases sensitivity to DEP-induced lung inflammation is a significant finding since Gclm is a highly polymorphic gene that has been already shown to influence the risk of MI and vasomotor dysfunction (Nakamura et al., 2002; Nakamura et al., 2003). Nakamura (2002) reported that in a Japanese sample of healthy controls, at least one copy of the —588C/T SNP within the 5′ promoter region of Gclm was present in 20.3% of individuals, this number increased to 31.5% in individuals presented in the clinic with an established MI. This SNP results in a greater than 50% reduction in promoter activity, slightly decreased serum GSH, and roughly a two-fold increase in the risk of MI (Nakamura et al., 2002). Moreover, these researchers found that individuals containing two copies of the polymorphism (frequency = 1%–3%) have a greater than eight-fold increase in the risk of MI. Further work done by Nakamura and colleagues have shown that this SNP within the Gclm 5′ promoter region is also associated with decreased coronary artery response to the endothelium dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (Nakamura et al., 2003).

In addition to investigations into the influence of GCL polymorphisms on vascular function, SNPs in the 5′ promoter region of Gclm and Gclc have been investigated with regard to compromised lung function and development of COPD in smokers (Chappell et al., 2008; Siedlinski et al., 2008). A large amount of cigarette smoke-induced lung injury has been posited to be due to the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and resulting oxidative stress (Kirkham and Rahman, 2006; Kirkham et al., 2003; Nakayama et al., 1989). As these SNPs in Gclm and Gclc have been demonstrated to reduce oxidant-induced expression of their respective genes in endothelial cells by nearly 50% (Koide et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2002), it was hypothesized that these polymorphisms would accelerate lung function decline and increase the risk of COPD in smokers. Although no associations were found between COPD and SNPs within both Gclm and Gclc (Chappell et al., 2008; Siedlinski et al., 2008), it was observed that smokers who also had these SNPs in Gclc had a significant acceleration of lung function decline when measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (Siedlinski et al., 2008). Providing further evidence that this association is due to loss of available antioxidants, this accelerated decline in lung function was found to be most significant in individuals with low intake of vitamin C. This finding suggests that polymorphisms in GCL may have a strong gene-environment interaction toward additional environmental toxicants that cause injury through an oxidative stress-mediated mechanism, such as diesel exhaust.

Our finding that Gclm modulation increases DEP-induced pulmonary inflammation is interesting in that the increased susceptibility is only dramatically present in mice heterozygous for Gclm. The Gclm−/+ mice had a significantly increased percentage of BALF neutrophils when compared to both WT and Gclm−/− mice, while inflammatory cytokines in their BAL were elevated when compared to WT mice but not to Gclm−/− mice. Alternatively, at the cytokine mRNA level, Gclm−/− mice seemed to have a greater inflammatory response compared to WT or Gclm−/+ mice. In an attempt to elucidate this contradiction, we hypothesized that the lack of neutrophil infiltration in the Gclm−/− mice was due to compromised metalloproteinase activation, but analyses of MMP and MPO failed to support the contention that Gclm−/− mice had recruited neutrophils to the lung interstitium but were unable to mediate neutrophil translocation into the alveolar space.

It is unclear why Gclm−/− mice would have an increased response to DEP by gene expression analysis but not have an increase in BALF neutrophils or inflammatory cytokines. As we know that Gclm−/− mice have many genes dysregulated, it is possible that the expression of certain classes of genes responsible for post-translational cytokine release, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor α Converting Enzyme (TACE), or genes responsible for regulating neutrophil influx (Gro1/KC or Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases) are also dysregulated. Alternatively, enzyme activity or protein function within the Gclm−/− mice may be influenced by compensatory increases in other antioxidant enzymes, decreased glutathiolation, or altered S-nitrosylation mediated by S-nitrosoglutathione, further leading to compromised cytokine release or neutrophil influx. In any case, expression of inflammatory gene mRNAs may increase, whereas the level of inflammatory cytokines or neutrophils found in the BALF may not. The reasons for these discrepancies are at present unknown and are the subject of future research.

Upon analysis of lung GSH, it is clear that Gclm−/− mice have dramatically low GSH than WT mice (~5% of normal), but Gclm−/+ mice have a relatively normal level of GSH compared to WT mice. Because of the dramatic reduction in intracellular GSH, Gclm−/− mice have likely adapted by dramatically upregulating other genes involved in protection from oxidant injury. In a previous report (Haque et al., 2010), we found that Gclm deficiency appeared to have led to metabolic adaptations that were protective toward diet-induced steatohepatitis in the liver. Some of the protective genes that are upregulated in the livers of Gclm−/− mice include: glutathione-S-transferases (Gsta2, Gstm1, Gstm2, Gstm3, Gstm4), sulfotransferases (Sult2A2, Sult3S1), glutathione reductase (Gsr1), Gclc, thioredoxin reductase 1, and PPARγ. In addition to these changes observed in the liver, Johansson et al. (2010) demonstrated that Gclm−/− mice are not more sensitive to ozone-induced lung injury as compared to Gclm WT mice. Although they observed that Gclm−/− mice did have dramatically reduced total of GSH at the cellular level, GSH in the ELF was not reduced in the Gclm null mice, suggesting a compensatory response to maintain normal GSH levels in the ELF. As well as an adaptive response in GSH level in the ELF, Johansson et al. observed that Gclm−/− mice upregulated expression of metallothionein 1/2 (MT1/2) in response to ozone to a much greater extent than Gclm WT mice, suggesting that these mice have the capacity to respond to oxidant injury by alternative means.

The Gclm−/− mice are unique in that they have a dramatic reduction in GSH, providing an excellent tool for investigating the biological function of GSH and the role of GSH in mediating toxicant injury (e.g. acetaminophen-induced liver injury), but as demonstrated, they are not necessarily more susceptible to general oxidants such as DEP or ozone (Johansson et al, 2010). The Gclm−/+ genotype is an interesting model in that these mice do not have dramatically low GSH compared to WT. That they respond much more robustly to DEP-induced inflammation may reflect an inability to produce GSH fast enough when under oxidative stress. Although our data only suggests this trend, analysis of Gclm protein levels seemed to indicate that DEP treatment causes a slight increase in Gclm expression in WT mice where this trend is not present in Gclm−/+ mice. This finding may suggest that to maintain normal GSH level under oxidant injury, WT mice were able to upregulate the expression of Gclm to increase GCL activity, and due to the presence of only one functional copy of the gene in Gclm, Gclm−/+ mice are possibly “maxed out” in their ability to further induce this protein. Thus the lack of one Gclm copy in Gclm−/+ mice, although sufficient to maintain normal levels of GSH under non-stressed conditions, may not be sufficient during periods of elevated oxidative stress.

Conclusions

As inflammation has been suggested to be a critical determinant of many effects in the lung and the vascular system following exposure to PM2.5, it is important to examine genetic factors that might influence the inflammatory response following diesel exhaust and PM2.5 exposure. We believe that our findings support the contention that DEP induces inflammation via a mechanism dictated in part by oxidative stress and that GSH plays a role in mediating the resulting inflammatory response. These findings can further suggest that individuals with compromised GSH synthesis, such as those with polymorphisms in GSH synthesis genes, may be an important population to investigate for increased sensitivity to ambient air pollution. If they are more susceptible, current regulations for PM2.5 should be adjusted to provide the necessary protection to these and other sensitive individuals.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

This work was supported by NIH Grants P50ES015915, P30ES007033, P01HL098067, and 5T32ES007032, and a grant from the Parker B. Francis Foundation.

References

- Banerjee A, Trueblood MB, Zhang X, Manda KR, Lobo P, Whitefield PD, Hagen DE, Ercal N. N-acetylcysteineamide (NACA) prevents inflammation and oxidative stress in animals exposed to diesel engine exhaust. Toxicol Lett. 2009;187:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bea F, Hudson FN, Chait A, Kavanagh TJ, Rosenfeld ME. Induction of glutathione synthesis in macrophages by oxidized low-density lipoproteins is mediated by consensus antioxidant response elements. Circ Res. 2003;92:386–393. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059561.65545.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bea F, Hudson FN, Neff-Laford H, White CC, Kavanagh TJ, Kreuzer J, Preusch MR, Blessing E, Katus HA, Rosenfeld ME. Homocysteine stimulates antioxidant response element-mediated expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase in mouse macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta D, White CC, Vliet-Gregg P, Mohar I, Shi S, McGrath MB, McConnachie LA, Kavanagh TJ. Modulating GSH synthesis using glutamate cysteine ligase transgenic and gene-targeted mice. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40:465–477. doi: 10.1080/03602530802186587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell S, Daly L, Morgan K, Guetta-Baranes T, Roca J, Rabinovich R, Lotya J, Millar AB, Donnelly SC, Keatings V, MacNee W, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS, Miniati M, Monti S, O’Connor CM, Kalsheker N. Genetic variants of microsomal epoxide hydrolase and glutamate-cysteine ligase in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:931–937. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Pope CA, 3rd, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG, Jr, Speizer FE. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein JN, Johnston C, Barrett T, Oberdörster G. Particulate-cell interactions and pulmonary cytokine expression. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 5):1179–1182. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s51179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin CC, Backos DS, Mohar I, White CC, Forman HJ, Kavanagh TJ. Structure, function, and post-translational regulation of the catalytic and modifier subunits of glutamate cysteine ligase. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Kassim SY, Parks WC, Heinecke JW. Hypochlorous acid oxygenates the cysteine switch domain of pro-matrilysin (MMP-7). A mechanism for matrix metalloproteinase activation and atherosclerotic plaque rupture by myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41279–41287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Belmadani S, Picchi A, Xu X, Potter BJ, Tewari-Singh N, Capobianco S, Chilian WM, Zhang C. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces endothelial dysfunction in Lepr(db) mice. Circulation. 2007;115:245–254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.650671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SE, Huizar I, Bench EM, Sussman SW, Wang Y, Khokha R, Parks WC. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 regulates resolution of inflammation following acute lung injury. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:64–73. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SE, Parks WC. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: Regulators of wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1334–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould T, Larson T, Stewart J, Kaufman JD, Slater D, McEwen N. A controlled inhalation diesel exhaust exposure facility with dynamic feedback control of PM concentration. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:49–52. doi: 10.1080/08958370701758478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque JA, McMahan RS, Campbell JS, Shimizu-Albergine M, Wilson AM, Botta D, Bammler TK, Beyer RP, Montine TJ, Yeh MM, Kavanagh TJ, Fausto N. Attenuated progression of dietinduced steatohepatitis in glutathione-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1704–1717. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happo MS, Salonen RO, Hälinen AI, Jalava PI, Pennanen AS, Dormans JA, Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Cassee FR, Kosma VM, Sillanpää M, Hillamo R, Hirvonen MR. Inflammation and tissue damage in mouse lung by single and repeated dosing of urban air coarse and fine particles collected from six European cities. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:402–416. doi: 10.3109/08958370903527908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Fischer P, van Wijnen J. The association between air pollution and heart failure, arrhythmia, embolism, thrombosis, and other cardiovascular causes of death in a time series study. Epidemiology. 2001;12:355–357. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200105000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Goldbohm S, Fischer P, van den Brandt PA. Association between mortality and indicators of traffic-related air pollution in the Netherlands: A cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360:1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E, Wesselkamper SC, Shertzer HG, Leikauf GD, Dalton TP, Chen Y. Glutathione deficient C57BL/6J mice are not sensitized to ozone-induced lung injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Spix C, Schwartz J, Balducci F, Medina S, Rossi G, Wojtyniak B, Sunyer J, Bacharova L, Schouten JP, Ponka A, Anderson HR. Short-term effects of ambient sulphur dioxide and particulate matter on mortality in 12 European cities: Results from time series data from the APHEA project. Air Pollution and Health: A European Approach. BMJ. 1997;314:1658–1663. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7095.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham P, Rahman I. Oxidative stress in asthma and COPD: Antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:476–494. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham PA, Spooner G, Ffoulkes-Jones C, Calvez R. Cigarette smoke triggers macrophage adhesion and activation: Role of lipid peroxidation products and scavenger receptor. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:697–710. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide S, Kugiyama K, Sugiyama S, Nakamura S, Fukushima H, Honda O, Yoshimura M, Ogawa H. Association of polymorphism in glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit gene with coronary vasomotor dysfunction and myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewtas J. Air pollution combustion emissions: Characterization of causative agents and mechanisms associated with cancer, reproductive, and cardiovascular effects. Mutat Res. 2007;636:95–133. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Takizawa H, Kawada T. Role of oxidative stresses induced by diesel exhaust particles in airway inflammation, allergy and asthma: Their potential as a target of chemoprevention. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2010;9:300–305. doi: 10.2174/187152810793358787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Takizawa H, Azuma A, Kohyama T, Yamauchi Y, Takahashi S, Yamamoto M, Kawada T, Kudoh S, Sugawara I. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to airway inflammatory responses induced by low-dose diesel exhaust particles in mice. Clin Immunol. 2008;128:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnachie LA, Mohar I, Hudson FN, Ware CB, Ladiges WC, Fernandez C, Chatterton-Kirchmeier S, White CC, Pierce RH, Kavanagh TJ. Glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit deficiency and gender as determinants of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99:628–636. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudway IS, Stenfors N, Duggan ST, Roxborough H, Zielinski H, Marklund SL, Blomberg A, Frew AJ, Sandström T, Kelly FJ. An in vitro and in vivo investigation of the effects of diesel exhaust on human airway lining fluid antioxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Kugiyama K, Sugiyama S, Miyamoto S, Koide S, Fukushima H, Honda O, Yoshimura M, Ogawa H. Polymorphism in the 5′-flanking region of human glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit gene is associated with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:2968–2973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019739.66514.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Sugiyama S, Fujioka D, Kawabata K, Ogawa H, Kugiyama K. Polymorphism in glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit gene is associated with impairment of nitric oxide-mediated coronary vasomotor function. Circulation. 2003;108:1425–1427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091255.63645.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T, Church DF, Pryor WA. Quantitative analysis of the hydrogen peroxide formed in aqueous cigarette tar extracts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordenhäll C, Pourazar J, Blomberg A, Levin JO, Sandström T, Adelroth E. Airway inflammation following exposure to diesel exhaust: A study of time kinetics using induced sputum. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:1046–1051. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Dockery DW, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:2810–2815. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Döring A, Wichmann HE, Koenig W. Increased plasma viscosity during an air pollution episode: A link to mortality? Lancet. 1997;349:1582–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, Thurston GD. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourazar J, Mudway IS, Samet JM, Helleday R, Blomberg A, Wilson SJ, Frew AJ, Kelly FJ, Sandström T. Diesel exhaust activates redoxsensitive transcription factors and kinases in human airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L724–L730. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00055.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi S, Blomberg A, Rudell B, Kelly F, Sandström T, Holgate ST, Frew A. Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:702–709. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9709083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, Godden D. Particulate air pollution and acute health effects. Lancet. 1995;345:176–178. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedlinski M, Postma DS, van Diemen CC, Blokstra A, Smit HA, Boezen HM. Lung function loss, smoking, vitamin C intake, and polymorphisms of the glutamate-cysteine ligase genes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:13–19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1749OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenfors N, Nordenhäll C, Salvi SS, Mudway I, Söderberg M, Blomberg A, Helleday R, Levin JO, Holgate ST, Kelly FJ, Frew AJ, Sandström T. Different airway inflammatory responses in asthmatic and healthy humans exposed to diesel. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:82–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00004603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Wang A, Jin X, Natanzon A, Duquaine D, Brook RD, Aguinaldo JG, Fayad ZA, Fuster V, Lippmann M, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S. Long-term air pollution exposure and acceleration of atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation in an animal model. JAMA. 2005;294:3003–3010. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Yue P, Ying Z, Cardounel AJ, Brook RD, Devlin R, Hwang JS, Zweier JL, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S. Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1760–1766. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SA, White CC, Krejsa CM, Diaz D, Woods JS, Eaton DL, Kavanagh TJ. Induction of glutamate-cysteine ligase (gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase) in the brains of adult female mice subchronically exposed to methylmercury. Toxicol Lett. 1999;110:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnqvist H, Mills NL, Gonzalez M, Miller MR, Robinson SD, Megson IL, Macnee W, Donaldson K, Söderberg S, Newby DE, Sandström T, Blomberg A. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:395–400. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-872OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Dieter MZ, Chen Y, Shertzer HG, Nebert DW, Dalton TP. Initial characterization of the glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit Gclm(−/−) knockout mouse. Novel model system for a severely compromised oxidative stress response. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49446–49452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Seki T, Naito Y, Tachibana S, Hirabayashi N, Nakasaka T, Ohara N, Kobayashi H. Tracheal instillation of diesel exhaust particles component causes blood and pulmonary neutrophilia and enhances myocardial oxidative stress in mice. J Toxicol Sci. 2008;33:609–620. doi: 10.2131/jts.33.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Canner MJ, Stone PH, Schwartz J, Sher D, Eagan-Bengston E, Gates KA, Hartley LH, Suh H, Gold DR. Ambient pollution and blood pressure in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Circulation. 2004;110:2184–2189. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143831.33243.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]